19

ALASKANS LEARN THEY’RE NOT ALONE

In those first hours after the devastating earthquake and tidal waves of Good Friday 1964, the overwhelming emotion for many Alaskans was one of isolation. In most of the stricken towns, local radio and television stations dropped off the air when electricity went out. No one knew what was happening in other parts of Alaska, nor if their family and friends were dead or alive. Alaskans felt alone and cut off.

Some people picked up news reports from the Lower 48 on transistors and battery-powered radios, and slowly Alaskans learned about the damage done to the state. They also learned that people across the globe were concerned for the people of Alaska.

One of the first messages heard came from Britain’s Queen Elizabeth, who had expressed her sympathy to U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson. So before they tried to rest that long, dreadful night, many Alaskans did not feel so alone anymore. They knew the world cared about them just as they cared about each other.

“Alaska was one big family,” Mrs. Ross McCoy told Alaska historian Phyllis Downing Carlson in the late 1960s. Her husband had been lost when the Valdez dock collapsed, but “everyone was wonderful – if they had and you didn’t, they shared with you – clothes, food, money.”

Many Valdez refugees evacuated to Fairbanks, which hardly felt the quake. Some learned firsthand the generosity of people from the Golden Heart City when three men entered a hotel that lodged refugees.

More than 100 refugees from Southcentral Alaska were taken to the Interior town of Fairbanks following the devastation of the 1964 earthquake.

“Are you from Valdez?” they asked, and then passed out $50 bills from their pockets to each Valdez family staying there (about $380 in 2015 dollars).

The refugees praised the kind hearts of those who lived in that Interior town.

“Here in Fairbanks, we don’t need money,” one refugee said. “Anything we need, somebody helps us with.”

Other towns and villages across Alaska pitched in to help, too. Around 200 laborers, 30 carpenters, 31 carpenter helpers, 32 heavy equipment operators and 32 truck drivers from Kotzebue, Point Hope, Kivalina, Kiana, Shungnak, Noorvik, Noatak, Selawik and Buckland offered to help rebuild the stricken areas. Barrow, the nation’s most northern community, quickly began raising a disaster fund. And from undamaged Juneau, Ketchikan and other Southeast communities came an overwhelming flood of concern and offers of assistance.

Alaskans learned there were no rich or poor. The earthquake not only leveled buildings, it also leveled distinctions, political as well as financial and social. Politicians forgot their differences and all Alaskans were united in their misfortune.

Americans everywhere moved rapidly to help their northern brothers and sisters. The Salvation Army kept a steady flow of supplies on the way to displaced families. And using Seattle as its base, the American Red Cross immediately organized their facilities.

“I’ve never seen anything like this,” said Seattle Red Cross chapter manager Joseph Hladecek in the days following the disaster. “Everyone wants to do something to help out in some way.”

The hearts of people all across the nation especially went out to those from Seward, selected that year for the All-American City award. Seward, one of the smallest cities ever to receive the honor, had planned to celebrate the distinction by inviting the public to two days of festivities on April 4 and 5.

Seward’s All-American sister cities created a campaign, Save Our Seward, to help the townspeople recover.

The disaster that shattered the little city on Resurrection Bay changed all that, but at the suggestion of one of Seward’s All-American sister cities, Allentown, Pa., a trust fund called SOS – Save Our Seward – was established. Other All-American cities rallied around, including Alexandria, Va; Woodstock, Ill.; Roseville, Calif.; Gastonia, N.C.; and Woodbridge, N.J. Missouri’s town of Neosha, named an All-American City in 1957, sent a check for $1,000 to help rebuild.

“One of the things that brought us up from nearly a knockdown was your wonderful wires,” responded Seward’s mayor Perry Stockton to all the well wishes and assistance. “We have just postponed our All-American celebration.”

Seward’s residents agreed – their city had suffered a great deal, but Seward’s spirit remained unbroken.

The spirits of all Alaskans who lost loved ones, homes, businesses and prized possessions on Good Friday were heartened by the good will of their fellow Americans, including a few young people from Hawaii and New York.

Three youngsters at Kailua, Hawaii, staged a backyard play, sold tickets and turned over their entire proceeds of 83 cents to the Red Cross to help the earthquake victims.

John Loeb Beaty, almost 7, of Port Jefferson, N.Y., also sent some money to Anchorage.

“Dear Mr. Mayor,” read the printed letter addressed to mayor George Sharrock. “I feel so sorry about your earthquake. I wanted to send you my Easter basket, but Daddy said the eggs wouldn’t last. I’m sending you one dollar, instead.”

Some New York teens collected 1,000 new dresses made by youngsters participating in the Mobilization for Youth Inc. vocational training program. The boys and girls voted to give the dresses to Alaska kids, and they drove to Washington, D.C., to present the gift to the Alaska Congressional delegation.

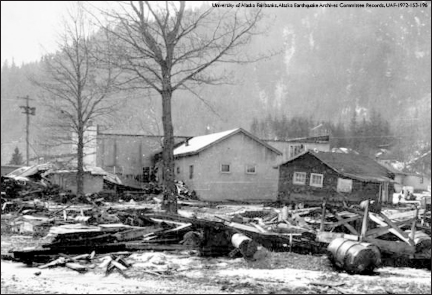

People and businesses around the world sent money to help towns like Valdez, pictured here, recover from the Good Friday earthquake in 1964.

Oregon lumbermen donated 3 million to 5 million board feet of lumber to help rebuild Alaska. The government provided the ship and the longshoremen donated their time and labor in packaging and loading it. The Carpenter’s Union contributed $50,000 to the disaster fund and the AFL-CIO turned over $25,000 to Red Cross and Salvation Army officials. Employees at Sicks Rainier Brewing Co. asked that company funds, normally used for their annual picnic, be donated instead to needy Alaskan families.

The International Telephone and Telegraph Corp. contributed $5,000 immediately to the city of Valdez, and said that more would be forthcoming when they had a better picture of the city’s needs. National businesses from across the United States increased deposits and opened new accounts in Alaska banks to aid in making funds available for reconstruction work.

Jose Iturbi, famous Basque conductor, harpsichordist and pianist, offered to give a benefit concert to help disaster victims, and light heavyweight boxer Eddie Cotton of Seattle offered to fight a charity bout with proceeds to go to the quake victims.

Tons of supplies from the Lower 48 arrived in Alaska and were quickly unloaded and distributed to communities in need.

Civilian, Army and Navy planes airlifted tons of supplies from heavy-duty machinery to newspapers. Sweating loadmasters performed amazing feats loading planes in a short time working 12-hour shifts without let up.

On April 3, a wrong-way Santa Claus traveled north in a jet instead of a reindeer-drawn sleigh. On board was the first of 10,000 pounds of toys destined for Alaska children. The project snowballed after it was started by a disc jockey in Seattle. Toys poured in from far and wide across the state of Washington.

While the generosity of Alaska’s fellow countrymen was overwhelming, people from other countries sent help and sympathy, as well.

The residents of Skopje, Yugolavia, who had previously gone through an earthquake, recalled with gratitude the help extended them at that time and the town’s mayor cabled a message of sympathy to Alaska Gov. William A. Egan.

The Japanese government donated $10,000. Its people knew firsthand the devastation wrought by earthquakes. Messages of sympathy also were sent to President Lyndon B. Johnson and Secretary of State Dean Rusk from Asian, African, European and South American countries. Canadian Prime Minister Lester Pearson sent a letter, as well.

“… I should be grateful if you would convey our deep sympathy to those in Alaska who have suffered such heavy and painful loss … I know I speak for all Canadians when I assure you that we stand ready to do whatever we can to assist the people of Alaska at this tragic time.”

A gift from a Canadian child, Wendy Loydhouse of Queensland Road in Vancouver, B.C., heartened Gov. Egan as he struggled to cope with all the disaster problems.

“To the dear children. This money is for you,” said the message in childish handwriting on a note wrapped around a Canadian $1 bill.

Alaska Gov. William A. Egan surveyed the damage at the Anchorage Turnagain-By-The-Sea subdivision following the earthquake on March 27, 1964.

The Apostolic Delegate to the United States, Egidio Vionozzi, had last visited Alaska in 1961 when he laid the cornerstone for the new Catholic Junior High School in Anchorage. He visited the state soon after the earthquake to bring a $10,000 check for the disaster fund, and to convey the Pope’s blessing to all Alaskans. Vionozzi told Alaskans that Pope Paul asked them to have confidence in Divine Providence in their hour of trial and said that they were showing the true spirit of pioneers in refusing to be overcome by adversity and misfortune.

Alaskans showed the pioneer spirit that carved a state out of a wilderness, and there were many stories to show that they did not allow misfortune to overwhelm them.

For instance, Anchorage city employee Patricia Mayo, who worked long overtime hours and refused to fill out a time ticket, instead wrote on its back: “This is my city. I do not expect to be paid for helping to bring it back to life!”

Hundreds of Alaskans showed their best sides as they picked themselves up, brushed off the dust and set about to make Alaska whole again. Volunteer nurses, some of whom had not worked at their profession for 20 years, left their homes and families to fulfill the mission for which they had been trained. City crews worked around the clock to restore power, water, phone and sewer services as rapidly as possible, while volunteers searched through tumbled houses and swaying buildings for survivors and to carry out people’s keepsakes and valuables. And many people whose world looked pretty dark with loss of homes, life savings and livelihood, volunteered to help with the rescue and rehabilitation work.

Business owners offered space to other businessmen whose buildings were damaged during the earthquake, like this one in downtown Anchorage.

Businessmen, whose stores and facilities were usable, generously made room for those in need, even their competitors. R.E. Grier, manager of quake-ruined Anchorage J.C. Penney, sent letters to all Penney charge customers directing “those unable to make their payments because of earthquake losses or the need to divert finances to emergency needs to postpone payments until your affairs have improved.”

A similar notice was sent to patients of the Holmes Johnson Clinic in Kodiak: “If you have extensive property loss due to earthquake, please contact us, and we will hold your statement.”

Perhaps the story of Sister Phillias, nursing supervisor at Providence Hospital in Anchorage, best epitomizes the selflessness and devotion to duty displayed by Alaskans following this tragic event.

Recovering from major spinal surgery when the quake struck, the nun saw the double glass window in her room lurch from its frame and felt her bed slide five feet across the room. She was convinced that her services were needed to pitch in with the others. Even though she was not able to be back on nursing duty, she did her bit by standing in the lobby directing visitors and answering questions.

“Alaskans and Providence Hospital proved themselves worthy of each other,” said Sister Barbara Ellen on Easter morning. “Both performed nobly. Nothing less than a superlative effort would have succeeded.”

Nothing less than a superlative effort, indeed. The earthquake dealt a staggering blow to Alaska’s economy. A few days following the disaster, experts estimated the new state had suffered between $350 million to $750 million in damages. And no one knew what effect it would have on the fishing industry, tourism or other sources of income for the new state.

Officials in Washington, D.C., immediately moved to provide long-term reconstruction funds. President Johnson, both parties and houses within Congress and the American people supported using federal money to rebuild Alaska as soon as possible.

“No community, no state, no corporation, can meet such a calamity,” stated an editorial in the Pittsburgh Press four days after the quake. “This, then, is a legitimate role for the federal government. It is legitimate because no one else has the capability. And whatever the government does can be justified because some of its citizens are in grievous need. Moreover, rubble and wreckage pay no taxes – the sooner the energetic Alaskans get back in business, the sooner they will repay Uncle Sam.”

With well wishes from so many people all around the world, and financial assistance from the federal government, Alaskans did, indeed, get back to business. The motto across Alaska became, “Better than before.”

Military Lends a Helping Hand

Alaskans’ grit and determination helped the 49th state rebound from the largest earthquake to hit North America in recorded history. But the military effort, code named Operation Helping Hand, made it happen.

The Office of Emergency Planning – predecessor of the Federal Emergency Management Agency – immediately worked with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to jump into action.

Less than 10 hours after the initial shake, emergency teams in small aircraft were assessing damage. Within a few days, a special projects office had been established in Anchorage, Valdez and Seward to award contracts for demolition and clearing debris, as well as repairing water supplies, sewer systems, power sources, fuel supplies and communications systems.

Hardhats and helmets replaced Easter bonnets that first weekend. And the Corps of Engineers made clearing roadways a priority.

Operation Helping Hand delivered many supplies, including food, clothing and medicine, to Alaska towns devasted by the Good Friday earthquake and tsunamis of March 27, 1964.

“It took us 12 hours to cut through the biggest slide,” one bulldozer operator later said. “And when we got through, there was another just ahead.”

Alaska, which became a state five years earlier, had limited disaster-response capabilities. But it did have military bases loaded with highly trained troops. U.S. Navy and Coast Guard personnel were stationed at Kodiak; Army troops at Fort Greely; Army at Fort Richardson and Air Force at Elmendorf in Anchorage; and Army at Fort Wainwright and airmen at Eielson in Fairbanks. Alaska National Guard troops, in Anchorage for an annual two-week training program, were kept in town for an extra three days to protect businesses and homes from looters.

The day after the earthquake, 17 C-123 Providers took off from Elmendorf Air Force Base and carried equipment and supplies to Kodiak, Valdez and Seward. Operation Helping Hand delivered 3.7 million pounds of cargo to several devastated towns during the first three weeks of the operation.

The massive airlift operations by the Military Air Transport Service shattered records during this time, flying more than 1,300 hours to haul in more than 2.5 million pounds of cargo – from baby food to heavy equipment – from Lower 48 bases, according to military records. More aircraft arrived from McGuire Air Force Base in New Jersey with electric generators and vans on Easter Sunday.

The largest project during this time involved the Military Air Transport Service, the Alaska Air Command and the Air National Guard when they combined forces to move a 520,000-pound Bailey bridge from Elmendorf to the Kenai Peninsula to replace the bridge destroyed at Cooper Landing on the lower end of Kenai Lake. This type of bridge, frequently used during World War II, is built on site from a kit.

Army engineers trucked the bridge in sections from Eklutna, 25 miles north of Anchorage, to Elmendorf. Then it took five days and about 60 flights to get all the pieces of the bridge and installers on location.

Military pilots also flew hundreds more hours in small aircraft to photograph and film the massive destruction to help responders and geologists learn the extent of the damage.

Reconstruction averaged $1 million a month in Anchorage alone during the first year after the earthquake, according to Corps of Engineers’ records. Altogether, the Corps spent more than $110 million on salvage, rescue and rehabilitation efforts.