ALASKA LAND IN DISPUTE

21

HOMESTEADERS HEAD NORTH

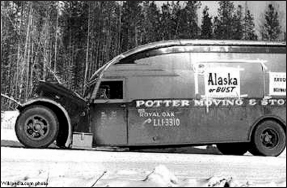

A couple of months after Alaska officially became a state, an intrepid band of Michigan folks, dubbed the “59ers,” left Detroit bound for Alaska. The caravan, consisting of 17 cars, six camper-trailers and a 1936 moving van named “The Monstrosity,” headed north on March 5, 1959.

Most of these adventurers had blue-collar jobs and hoped the grass might be greener in the Last Frontier. The group included bricklayers, carpenters, mechanics and other tradesmen who felt they had no future in Detroit with its stagnant economy and double-digit unemployment numbers.

They thought Alaska held more promise. For a filing fee of just a few dollars, they could claim a homestead and carve out fruitful lives for themselves and their children on the Kenai Peninsula.

The U.S. government first encouraged homesteading in the Continental United States during the mid-1800s when economic and social changes gripped the developed Eastern states. People looked to the west and the vast underdeveloped lands with a rather romantic vision for new opportunities.

Known as the “Monstrosity,” this van was among the caravan of vehicles bound for Alaska that left Detroit, Mich., in March 1959.

In 1862, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Homestead Act with the idea that free land would help develop this unpopulated area. The act took effect on Jan. 1, 1863.

“An allusion has been made to the Homestead Law. I think it worthy of consideration, and that the wild lands of the country should be distributed so that every man should have the means and opportunity of benefitting his condition,” Lincoln said at the time.

Special legislation extended the provisions of the act to the territory of Alaska in 1898. General homesteading requirements from the Bureau of Land Management were to:

1) Be age 21 or older, or the head of a household, or served in the military

2) Be a U.S. citizen or filed a declaration to become one (had to be a citizen before the homestead could be patented)

3) Live on their claimed land for most of five consecutive years (after June 6, 1912, it was decreased to three years)

4) Never borne arms against America or aided its enemies

5) Live in a habitable dwelling (a tent would not count)

6) Cultivate at least one-eighth of their land (grain or vegetable crops were typical, but raising hay for horses was allowed since it was a commercial crop)

But homesteading in the remote territory didn’t catch on much due to poor weather and poor soils. Less than 200 homestead applications had been filed in Alaska by 1914.

Alaska homestead applications increased after World War II and the Vietnam War, however. Those 20th-century pioneers were looking for the same land ownership opportunity that had lured settlers out to the Western states during the previous 100 years.

Alaska newspapers touted the benefits of homesteading to lure people north after statehood. And Alaska’s new U.S. Sen. Ernest Gruening often was quoted as saying, “We need people.”

Homesteaders used horses and wagons to haul supplies to their land on Cache Creek.

So the Detroit 59ers sold their homes, packed their belongings and headed toward a chance at a brighter future. And the press picked up on their plans.

“We are pooling all we know how to do in this cooperative venture that probably none could do alone,” 59er spokesman Ronald Jacobowitz said in an interview. “Everything we are doing, every plan made and carried out has been done by the vote and consent of all.”

The day of their departure, hundreds of people turned out to cheer them on their way – some gave them food and money. The Detroit News assigned a reporter to accompany the group and send updates from their journey. Life magazine sent photographer Bill Ray to capture their trials and tribulations.

Newspapers couldn’t get enough of the new stampeders. They churned out updates as the caravan made its way toward the Last Frontier.

“A cold expanse of snow and ice lies ahead,” reported one paper. Another said the north was a “wild country that will separate the men from the boys.” Yet another claimed the venture was “a test of men against virgin soil.”

By March 10, after driving along fog-shrouded and slippery highways, the group reached Fergus Falls, Minn. Three cars and two trailers became separated from the caravan during a heavy snowstorm. One station wagon got stuck.

The journey proved too much for nine families. They dropped out before reaching the border and returned to Michigan.

The rest of the group reached the Alaska Highway and Dawson Creek on March 15. Twelve days later, the 59ers pulled into Palmer after traveling 4,500 miles. Enthusiastic well-wishers greeted the bunch and welcomed them to the new state. Then the Alaska State Troopers escorted the caravan from Palmer into Anchorage, where a raucous celebration in their honor exploded along Fourth Avenue.

Sgt. Gardner B. White Jr. of Elmendorf Air Force Base entertained them with a song he had written in their honor, titled “My New Alaska Home.” Anchorage Mayor Hewitt Lounsbury welcomed them, too.

“You are the first pioneers of the new state,” Lounsbury told them.

The Hofbrau then treated the state’s newest pioneers to dinner.

“It’s great to be in Alaska,” said spokesman Jacobowitz in an interview for the Anchorage Daily Times on March 27.

Another 59er, Bertha Donaldson, said she was eager to get to Kenai and starting building a cabin. She was tired of traveling, boiling water over a campfire and sleeping in a trailer. But even though she and the other three-dozen 59ers were tired from their long drive north, they were glad to be in Alaska.

The Michigan 59ers reached Mile 0 of the Alaska-Canada Highway at Dawson Creek on March 15 – 10 days after leaving Detroit.

“We’d do it again,” Donaldson said, and added she had high expectations for the upcoming summer and had packed a swimming suit. She said more Michigan homesteaders might head north in the summer, too, if they were assured of a parcel of land measuring 10 square miles each.

Robert “Bob” Atwood put in his two cents, as well. Atwood, editor and publisher of the Anchorage Daily Times, had been a major supporter for the push toward statehood and hoped Alaska might grow to more than a million people in the not-to-distant future.

“Success of these people is important to every Alaskan,” he wrote in an editorial that welcomed the 59ers. “They are symbolic of the thousands of others who want to come here and make a home.”

The 59ers drove to Kenai on March 28. But once they arrived there and looked the area over, they did not find it to their taste. They decided instead to settle in the Susitna area where they thought the climate better for farming and larger tracts of land were available.

However, the Bureau of Land Management would not guarantee them contiguous blocks of land in Susitna – or anywhere else.

This winter view along the Kenai River in 1956 shows a small homestead on the right bank. When the 59ers finally arrived in Kenai, they decided they didn’t want to settle there and moved on to the Susitna Valley.

Between 1898 and 1903, people could claim up to 80 acres for a homestead. That acreage increased to 320 acres during 1903 to 1916. Then the Alaska homestead plan was revised so people only could claim 160 acres.

The requirements for living on the land changed from five years to three years in 1912, and in the 1950s an amendment changed allowable short leaves of absence so homesteaders had to live on their claims not less than seven months per year.

Other amendments followed for Alaska homesteads because cultivating land for crops was hard or impossible in the soil found in many areas of the state. Homesteaders faced other hardships, too, including remoteness, severely cold weather, short growing seasons, high cost of supplies, no market for crops and lack of roads.

New amendments also allowed people to claim up to five acres without cultivating the land if they lived on the land and built a habitable dwelling. They then had to pay $2.50 per acre at the end of the proving up process. These homesteads could be increased by another five acres if claimants showed that they needed the additional acreage for a business.

Some of the Michigan homesteaders claimed land around Talkeetna. And on June 25, another caravan with 76 new 59ers left Detroit and headed north to join those in the Susitna Valley.

Life in Alaska proved harder than most expected, though. They encountered many of the same hardships as their homesteading brethren of the 19th century, such as lack of transportation, harsh weather and the dangers posed by wildlife. Of the 21 families that originally came north from Detroit, only four earned their homestead patents by clearing, improving and living on their parcels of land.

One of those four, the Don Devore family, staked out land five miles north of Talkeetna at Mile 232 on the Alaska Railroad. At the time, Talkeetna was little more than a fishing village with no water, sewer or paved roads. The only access to the area was via train or air.

The Devores cleared their land during summers and put up firewood, preserves and food from their garden and canned salmon to get them through the long winters. They also hunted for wild game.

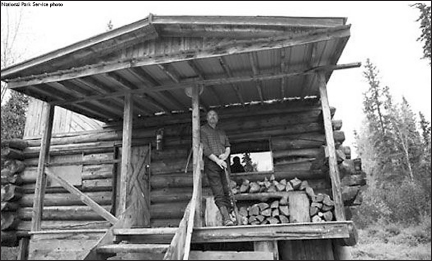

The Davore family, one of the original Detroit 59ers, built this homestead at Mile 232 along the Alaska Railroad route near Talkeetna.

“We would often down a moose in summer, and without a way to refrigerate the meat, we’d wrap the quarters in muslin and hang them high in a tree where the bears couldn’t get them,” Don Davore said in an email interview. “The outside two to three inches would crust over and be covered in white fly eggs – but once you cut into the heart of the meat, it was good eating!”

Life in the wilderness was not for the faint of heart. It took courage, determination and stamina.

“As a family, we learned self-reliance and survival on the barest of necessities,” Davore said. “Our nearest neighbor was four miles down the tracks toward Talkeetna. Our mail was thrown from a speeding train.”

When his father died suddenly in 1961, Don Davore said he and brothers Dennis and Gayland left the homestead to find work to help support their mother and younger siblings, Susie and Bruce, who stayed on the property.

He and Dennis found work on the railroad’s extra gang, and Gayland went to work on a farm in Palmer. Eventually, the entire family left the homestead.

Don Devore and his wife, Mavis, now live in Talkeetna. They built a rustic lodge called Denali Fireside, where travelers can stay in suites or cabins and enjoy “one of Alaska’s friendliest villages.”

The old Devore homestead cabin, one of the only remaining 59er cabins left in Alaska, still can be seen from the railroad. The deteriorating building also can be reached by hiking five miles up the railroad road tracks from Talkeetna. The area is considered “off grid” as it still has no roads, power or infrastructure and is serviced by the last “flag stop” train in North America.

Other areas of Alaska were settled as homesteaders made their way into the wilderness and claimed land in Southeast, Fairbanks and the Matanuska Valley. Homesteaders settled places near Knik, Takotna, Chickaloon, Seward, Homer and Bear Cove on Kachemak Bay. An article in the July 1959 Alaska Call describes how homesteads near Ninilchik on the Kenai Peninsula grew.

“Eight miles from Ninilchik on the way to Homer is a new settlement of homesteaders. There are 12 people: Rex Hanks, Ray Marx, Clyde Tomas, Vernon McMillan, Bill Nutte, Jim Nutte, George Welch with his wife and three children, and Joe Hoffman.”

And three miles up the beach from Ninilchik another group was carving out a living in the wilderness.

“Deep Creek has a small settlement that may grow in the future. Ed Nickolay, Bill Kashenko and Robert Morris live there. Roy Erickson, Polly Odman and her two sons, and Seymour with his wife and their child. …”

About two miles from Ninilchik and left of Deep Creek a new community called “Little Kansas” also sprung up.

“… a few young couples came into this area where probably no man ever lived before. Now there is a trail road for jeeps which leads to the homes … Their life is full of toil and hard work, but they are proud of their efforts and results are noticeable already. Their cabins, their gardens, their wells with modern pumps, their machinery for work on the land and with timber, and even their livestock indicate that they are serious about their permanent stay in the settlement.”

The Call article stated that all of the homesteaders are “newcomers from the Continental states, although some of them have spent considerable time in Alaska prior to taking homesteads. …” It also pointed out that the homesteaders had to find work off their claims in order to survive.

“… not one of those homesteaders was able to make any living on the homestead, but had to work in fishing, on the road, or make his living expenses in some other way.”

Homesteads were not only carved out of the remote regions of Alaska, either. Several homesteads in the Anchorage area were made possible when Congress passed Public Law 82 in 1947. It permitted veterans with at least 90 days of service to substitute up to two years of their military service to satisfy homestead residence and cultivation requirements.

Active duty servicemen could commute between Fort Richardson and their homesteads to prove up on their parcels of land. Others worked jobs in Anchorage and then returned to their families on the weekends to work on their homesteads.

Some early Anchorage homesteaders grew crops and others raised livestock. Hog farmer Tom Peterkin has a street named for his family in Mountain View.

Names of main thoroughfares like Muldoon, Boniface and Tudor pay homage to some of those early homesteaders. Other areas like the Hillside, Sand Lake, Eagle River and Chugiak began as homesteads where pioneers farmed potatoes and raised poultry and pigs.

The Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 repealed the Homestead Act in the Lower 48, but it granted a 10-year extension on claims in Alaska. When homesteading ended in Alaska on Oct. 21, 1986, few parcels of land had been available for the program for more than a decade. Tens of millions of acres of federal land had been withdrawn from homestead entry to allow the state and Native corporations to select land under terms in the 1958 Alaska Statehood Act and the 1971 Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act.

The last homesteader in the nation, Kenneth Deardorff, received patent to his Alaska claim in the late 1980s. The Vietnam War veteran from California had long dreamed of a life in the Far North, fueled by subscriptions to outdoor magazines from an uncle. He originally made his way to Alaska looking for work with the U.S. Geological Survey, but once in the Great Land, decided to homestead.

Kenneth Deardorff, seen here on the porch of his cabin on his homestead near Lime Village in western Alaska, was the last person to receive a patent under the 1862 Homestead Act in 1988.

Deardorff filed for an 80-acre parcel on the Stony River in Southwestern Alaska in 1974. Transportation to and from his homestead, about 200 air miles west of Anchorage, was via boat or dog team. He first pitched a small nylon tent in February and lived in that while building a small cabin. When his wife arrived, the couple began constructing buildings from white spruce trees on their land south of McGrath.

To help support his homesteading lifestyle, Deardorff opened a small general store on his property that catered to those traveling the Stony River. He also trapped for marten during the winter when temperatures often dipped to 65 degrees below zero.

He had fulfilled all the legal requirements of the Homestead Act by 1979, but the wheels of bureaucracy moved slowly. It took another nine years for him to receive the patent to that land.

In an interview published Sept. 1, 2012, with the Beatrice Daily Sun of Nebraska, Deardorff talked about his homesteading experience. Turns out the first homesteader in America, Daniel Freeman, applied for title to a 50-acre claim in Beatrice in 1863.

“I have a lot of mixed emotions about that time,” Deardorff said in the interview about his time in Alaska. “It was certainly enjoyable and certainly frustrating, but all in all absolutely rewarding and something I would do again.”

By the time Deardorff, who eventually moved to McGrath, received his patent on May 5, 1988, BLM had conveyed 3,277 homesteads in Alaska that equaled more than 360,000 acres – or less than 1 percent of the total land in the Last Frontier.

It took many years for the federal and state governments and the indigenous people of Alaska to settle once and for all the issue of who owned the remaining available land.