PRUDHOE BAY OIL

25

BLACK GOLD FOUND ON NORTH SLOPE

As prospectors searched for gold in the northern wilderness during the late 1890s, some sourdoughs stumbled across enough black goo along the Klondike River to spark the interest of reporters Outside.

“What is said to be the greatest discovery ever made is reported from Alaska. Some gold prospectors several months ago ran across what seemed to be a lake of oil. It was fed by innumerable springs, and the surrounding mountains were full of coal. It is stated that there is enough oil and coal in the discovery to supply the world,” reported an Associated Press dispatch on July 13, 1897.

But it took 60 years and 10 days of oilmen punching more than 100 holes in the frozen ground to find commercial quantities of crude. Then on July 23, 1957, Richfield Oil Co. struck black gold with a test well in the Swanson River region on the Kenai Peninsula. It pumped 900 barrels of oil per day on a short test.

News of the first tanker, F.S. Bryant, leaving the Kenai Peninsula filled with thousands of barrels of oil bound for the Lower 48 may be compared to the news of the SS Portland leaving St. Michael with its ton of Klondike gold in 1897. It had the same effect. Instead of miners looking for gold, though, it brought prospectors searching for oil.

Prospects for the petroleum industry in Alaska by 1966 looked bright. Alaska ranked 11th nationally in proved oil reserves and eighth in proved gas reserves.

Oil companies were producing oil and natural gas in the Kenai Peninsula and Cook Inlet, with 15 offshore oil platforms, onshore oil and gas wells, and large processing, refining and transportation facilities. They also were providing Alaskans with gasoline, diesel fuel, heating oil and jet fuel. And they built a pipeline beneath Turnagain Arm that carried natural gas from the Kenai Peninsula to heat Anchorage homes and businesses.

In September 1967, Cook Inlet monthly production surpassed that of Swanson River for the first time with 1,186,414 barrels compared with 1,090,528 for the Swanson. Experts believed the oil industry would continue to increase its activity in Alaska following its profitable production from the Swanson River and Cook Inlet areas and favorable results from seismic and geological exploration on the North Slope of the Brooks Range.

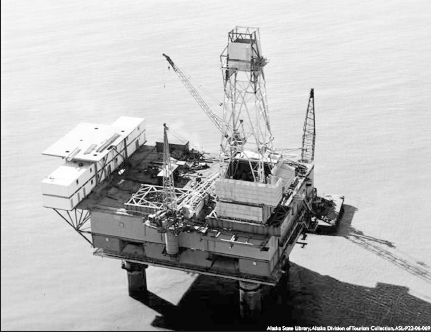

After crude was discovered near Kenai, oil companies began finding more deposits in Cook Inlet, as seen by this offshore rig near Anchorage. By late 1960, Alaska had 19 producing oil or gas wells and 18 major oil firms located in the state – 17 in Anchorage.

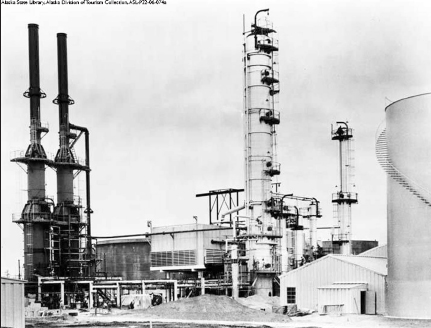

Following a major discovery of crude in 1957, Standard Oil Co. built Alaska’s first oil refinery at Nikiski, near Kenai. It opened on Oct. 10, 1961.

A pipeline linking the Swanson River Field with a marine tanker facility at Nikiski was dedicated on Oct. 1, 1960. Alaska’s U.S. Sen. Ernest Gruening stands to the far left of the group attending the ceremony. The Standard Oil Co. of California tanker W.H. Berg took on the first load of crude from the Nikiski terminal one month later on Nov. 12.

The Kenai Peninsula saw tremendous growth as workers and their families followed the drilling activity and homesteaders used oil well roads to access new lands.

Based on recommendations in 1964 of Tom Marshall, the state’s only geologist, Alaska had selected 1.5 million acres of the Arctic coastal plain bordering the Beaufort Sea between Naval Petroleum Reserve No. 4 and the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge as part of its land entitlement of 103 million acres granted under the Statehood Act. Marshall had recognized some general geological similarities of the Arctic Slope to areas in the Rocky Mountains that were producing petroleum. Even though the U.S. Navy and U.S. Geological Survey had been test drilling in the Arctic for decades with no commercially significant discoveries, Marshall believed the Arctic Slope probably held the richest oil land in Alaska.

USGS geologist Marvin Mangus spent nine field seasons working for the government and other parties between 1947 and 1958 on expeditions in the North Slope. But he did not find any deposits that would be commercially viable. He did discover a small field at Umiat, two small gas fields at Gubik and Barrow, three prospective gas fields at Meade, Square Lake and Wolf Creek, and two minor gas deposits near Cape Simpson and at Fish Creek, according to a recent article in Petroleum News.

But after 30 years of exploration in the reserve, at a cost of $50 million to $60 million, the federal government finally said enough in 1953 after drilling 75 test wells near Umiat. Congress no longer would appropriate money for a program that was not producing economically viable results.

Five years later, the government opened parts of the North Slope outside Naval Petroleum Reserve No. 4 to simultaneous filing of oil and gas leasing. That spurred oil companies to conduct geophysical and geological studies.

Aviator Noel Wien took this aerial shot of the U.S. Navy exploring for oil near Umiat.

In December 1960, the government made the area for finding commercial deposits of oil even smaller after it established the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, which covered almost 19 million acres. Between the refuge and the naval reserve, the oil industry now was limited to exploring acreage lying between the Colville and Canning rivers.

Exploration moved slowly due to problems with drilling and production in such a remote, frigid region.

In spite of the obstacles, several companies – including British Petroleum, Colorado Oil & Gas, Sinclair, Richfield Oil Co., Standard Oil Co. and Pan American Petroleum – were making exploratory drill tests in the vast area of 45 million acres lying north of Alaska’s Brooks Range by 1965, according to newspaper articles of the time.

“Everything was confidential,” said Mangus, who then worked for Richfield. “We didn’t trade maps unless we were partners with a company. Even then there was some secrecy.”

Geologists believed that Alaska’s Arctic Slope held the greatest petroleum potential of any geological province within the United States, however, because of its vast basin with tremendous thickness of marine sediments. Drilling done on Naval Petroleum Reserve No. 4 had shown those sediments contained both oil and gas. Experts just did not know if the area had “favorable reservoir conditions which are so essential for major accumulations of oil or gas,” said Rollin Eckis, president of Richfield, in a speech to the Greater Anchorage Chamber of Commerce in September 1964.

Transportation to the remote region was problematic, as well. There were no roads to the potentially oil-rich land, and passage via ship to Point Barrow was limited to a few weeks a year due to sea ice.

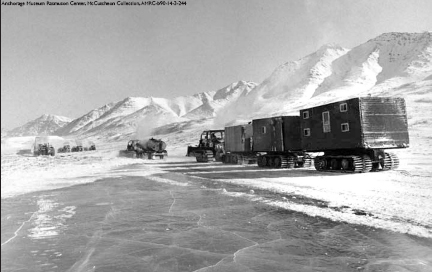

John C. “Tennessee” Miller decided to prove the feasibility of transporting men and equipment overland for the oil industry and convinced Richfield to let him try during the winter of 1964. Miller planned to take a caravan of Caterpillar tractors loaded with seismic exploration equipment from Fairbanks north through Anaktuvuk Pass, a low altitude pass that cuts through the Brooks Range from Bettles in the Yukon drainage to the Arctic Slope.

Miller, founder of Frontier Companies of Alaska Inc., spent two weeks staging supplies needed to establish a second Richfield Oil geophysical crew on the North Slope. He then set out on his quest, facing frigid temperatures, frequent equipment breakdowns and dangerous river crossings. It took 40 days to reach his destination – only 18 days were actual travel days, however. The rest were spent repairing equipment, waiting out bad weather and dealing with other hazards.

The Cat trip proved that the pass could be used to link to the Alaska Railroad, which increased the timeframe for shipping items to the North Slope to about seven months per year instead of a few weeks by sea. It also proved the versatility of the D7 Cat. The weight of the D8 was found to be dangerous on river crossings and the D6 too small for pulling sleds, according to a special publication from Petroleum News titled Harnessing a giant: 40 years at Prudhoe Bay.

Atlantic Refining and Richfield merged early in 1966 to become ARCO. Soon after the merger, ARCO district manager Harry Jamison persuaded Alaska Gov. Walter J. Hickel to make leases available near the Prudhoe Bay area for oil and gas leasing. Jamison thought if oil companies could lease land adjacent to Naval Petroleum Reserve No. 4, then exploration could go forward. Hickel agreed and opened seven critical tracts.

John C. “Tennessee” Miller proved that Caterpillar tractors could travel from Fairbanks to the North Slope through Anaktuvuk Pass in 1964.

Before 1966 closed, however, the federal government put a stop to Alaska choosing any more land from the 103 million acres granted it under the statehood act. U.S. Interior Secretary Stewart Udall imposed a “land freeze” on the transfer of lands claimed by Alaska Natives until Congress sorted out their claims.

“In the face of federal guarantee that the Alaska Natives shall not be disturbed in the use and occupation of lands, I could not in good conscience allow title to pass into others’ hands,” Udall said in a statement. “Moreover, to permit others to acquire title to the lands the Natives are using and occupying would create an adversary against whom the Natives would not have the means of protecting themselves.”

The seven tracts opened by Hickel had already been selected by the state, so those lease sales were not affected by the freeze. And a multitude of companies filed for leases on nearly 7 million acres in January 1967. As Jamison had predicted, exploration then began in earnest – although most companies drilled dry hole after dry hole, according to Petroleum News.

But even though they were feeling discouraged, the experts at ARCO would not give up.

“Once we asked the governor to put up those tracts, to me that was a clear signal,” Jamison later recalled. “You don’t renege on that obligation. Though it wasn’t a legal obligation, it was a moral one.”

ARCO partnered with Humble Oil, and the companies then shared maps and expertise to decide the most promising spots to sink test wells. Then 11 years after hitting its first producing well on Swanson River, ARCO hit the mother lode of crude along the Beaufort Sea coast on Alaska’s North Slope.

It happened the day after Christmas. When the crew opened a rig to check the results, they were surprised by natural gas bursting into the air. When it was ignited from a 2-inch pipe, it flared 50 feet in a 30 mph wind.

“In December (1967), we hit the oil, but they did not call the official discovery date until February or March of 1968,” Mangus recalled of the spudded Prudhoe Bay State No. 1 well that had been started in April 1967. “You didn’t want everyone to know.”

And so ARCO began 1968 with an understatement about its discovery. The company reported publicly that its State No. 1 well had a gas flow in “not a small amount.”

On Feb. 17, ARCO announced that its well had struck oil and “looks extremely good.” By March 13, the well had flow-tested at 1,152 barrels per day. In June, it tested at rates up to 2,415 barrels per day, and ARCO announced that its confirmation well at Sag River, seven miles away, was an oil producer, as well.

Communication between the drill site, offices in Anchorage and headquarters in the Lower 48 were rudimentary at best. Most messages were relayed via single sideband radio on a public frequency in the early days. Sometimes, when they couldn’t get through on the sideband radios, the drilling team used a ham radio operator in the camp to send messages via shortwave to another operator, who then placed collect telephone calls to relay messages to management. Secrecy at that time was not a priority.

But the ARCO discovery changed the way the crew communicated. Daily updates were relayed from geologists who flew from the North Slope to Fairbanks or Barrow to give daily drilling reports over secure phone lines.

“As a result, I, or one of the other well-site geologists, had a daily round trip commute of close to a thousand miles, just to make a couple phone calls and mail two or three letters,” said C.G. “Gil” Mull, who served as well-site geologist for Humble Oil on the Prudhoe Bay State No. 1 well, in a Petroleum News article titled “Talk far from cheap in early days.”

Eventually, ARCO set up a telephone relay system in camp to send secure messages. British Petroleum used a system akin to one developed during World War II to keep messages secret: code talkers. It sent one Welsh-speaking geologist to the drilling rig camp and another to its Anchorage headquarters to exchange messages in their native language.

The oil industry pumped into high gear on the North Slope after it discovered a massive oil field at Prudhoe Bay in 1968. This drilling rig is sending out a spray of steam during exploratory work in 1969. Additional wells were needed to define the limits of the field.

The 1968 bonanza, with an estimated capacity of 10 billion barrels of recoverable crude, was heralded in an engineering report that stated the North Slope discovery “appears to be one of the largest known petroleum accumulations in the entire world.” It covered 88,000 square miles, an area slightly larger than Idaho.

“This well was the last well that will probably be drilled on the North Slope, because everything had been dry holes,” Magnus later explained about what he was thinking before that well struck oil. “And by God, when I hit it, here comes this discovery well.”

Several more oil companies soon hit large pools, too, including BP Oil Corp., Mobil Oil and Phillips Petroleum.

Thus Prudhoe Bay was born. Soon the state would have nearly $1 billion in its coffers from lease sale No. 23. The total net received from the previous 22 lease sales during the state’s 10-year history had amounted to $97.6 million, according to Petroleum News.

Oil industry experts and executives from around the world converged on Anchorage in early September 1969. They crowded into hotels and motels across the city.

Most had spent considerable time that year secretly compiling information to make the best decisions on which parcels they wanted to lease. Reports of industry espionage ran rampant, including sightings of mysterious helicopters flying over test wells on the North Slope.

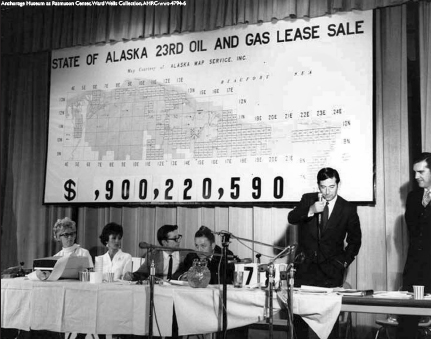

Oil companies, investors, state officials and more than 150 accredited newsmen representing newspapers, magazines, radio and television from all parts of the world filled the Sydney Laurence Auditorium on Sept. 10. State troopers and armed guards stood close by, as bidders handed over sealed envelopes that contained their bids for the tracts they believed held the most promise for big oil finds.

When the 164 bids on 179 tracts were opened that morning, it became apparent that many of the bidders had formed alliances to better their chances for successful bids. And prior bids for leases on the first 22 lease sales that went anywhere from $1 to around $50 per acre were eclipsed by bids in the thousands.

The highest bids came in for Tract 57, the closest land to the Prudhoe Bay oil discoveries. The Mobil-Phillips-Standard Oil of California group bid $72.1 million and was thought to be the winner by most in the auditorium. Until the Amerada-Getty Oil envelope revealed a bid of $72.3 million, the highest bid ever offered for a U.S. lease sale. That winning bid brought in $28,233 an acre for the state, which at the end of the day collected more than $900 million, or an average of $2,132 per acre for its 23rd lease sale that totaled 412,453 acres, according to the Anchorage Daily Times.

The 23rd oil and gas lease sale for drilling on the North Slope was held inside the Sydney Laurence Auditorium in Anchorage and brought more than $900 million to the state. Alaska Gov. Keith Miller, holding the microphone, and Department of Natural Resources commissioner Tom Kelly, standing far right, attended.

Not all Alaskans were happy about the oil and gas lease sales as seen by this group of protestors carrying signs outside the Sydney Laurence Auditorium while the bids were being opened on Sept. 10, 1969.

“A plane had been chartered to transport the checks to the Bank of America in San Francisco, while bankers were on hand to cancel the checks from unsuccessful bidders,” according to Petroleum News.

Once the lease sale was completed, the race was on to find the next bonanza. Oil companies used every mode of transportation to get crews and equipment to those high-priced acres – including the “Hickel Highway” out of Fairbanks.

The highway actually was the path bulldozed by Tennessee Miller and others along old Native trails across the tundra. One truck driver described the weather he encountered along the rough route as he drove a 20-ton transport truck in a convoy along that arctic ice road in 1968.

“We needed almost as much fuel to keep warm as to run the rigs,” Burn Roper said in a 1970 interview for an internal British Petroleum publication, adding that the temperatures were somewhere around minus 65 degrees Fahrenheit.

“At this temperature, steel was as brittle as candy; human flesh froze in 30 seconds,” Roper said. “Engines had to be kept running round the clock – from fall to spring, they never stopped.”

The oil drills did not stop either. And once oil in great quantities was discovered, the race to get all the pieces in place to get it to market went into high gear.

Naval Petroleum Reserve No. 4

When Wainwright schoolteacher William Van Valin learned about an oil lake on the Arctic coast near Cape Simpson southeast of Barrow during the summer of 1914, he staked a claim. He became the first wildcatter on Alaska’s North Slope, and his claim included seeps about a mile inland from Smith Bay.

Geologist Ernest de Koven Leffingwell traveled north in 1906 and spent seven years mapping the geology of what is now the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and surveying the Arctic coastline. He shared his information with the U.S. Geological Survey, which surmised that the area might hold a great deal of petroleum, but since it was so remote, probably would be of no value.

Standard Oil Co. of California sent agents to Cape Simpson in 1921. They did find oil seepages, but the company decided other areas of the country were more accessible and decided not to continue efforts in Alaska, according to Harnessing a Giant – 40 years at Prudhoe Bay by Petroleum News.

Although prospecting permits were filed under the mining laws in 1921, President Warren G. Harding’s administration withdrew large areas surrounding the seeps at Cape Simpson all the way south of the crest of the Brooks Range from oil and gas or mineral leasing in 1923. Nearly 23 million acres, or 38,000 square miles, of the Arctic Slope became the Naval Petroleum Reserve No. 4, and its creation was to ensure the World War I-era U.S. Navy would have future supplies of oil to fuel its fleet. Public Order No. 41 put about half of the Arctic Slope north of the Brooks Range off limits to commercial production. Today, that area is known as National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska.