27

PLANS FOR A PIPELINE PROGRESS

Once the largest oil field in North America was discovered, the big question became how to get that oil to market. Some thought it could be transported by giant tankers or oil-carrying submarines. Some thought a 2,900-mile pipeline across Canada to the Midwest might be the answer. Yet others believed an 800-mile line south to an ice-free port in Southern Alaska, where ocean-going oil tankers could be filled, would be the best bet.

Humble Oil, BP and ARCO supported the first option. The double-hulled SS Manhattan had proved an ice-breaking tanker could travel through the Northwest Passage and Alaska Arctic when it made a much-publicized round trip from the East Coast in the fall of 1969. The 115,000-ton tanker made another successful voyage the next spring. Further analysis proved this method was not commercially viable on a year-round basis, however, due to cost and unpredictable offshore ice conditions.

One company suggested nuclear-powered submarine tankers. Others pitched the idea of building a railroad from Prudhoe Bay to Alberta, Canada, where pipeline facilities already existed. Ideas for tanker aircraft, dirigibles and other airships were floated, also.

When the air cleared, two pipeline ideas proved most popular. One from Prudhoe Bay south to Valdez, or one that ran from the North Slope into Canada, via the Mackenzie River Valley to Alberta, to connect to the existing pipeline system that went over to Chicago and the Great Lakes industrial belt.

Studies showed a hot-oil Prudhoe-Valdez pipeline was the most economical. It crossed fewer permafrost areas, so would disturb the terrain less, and crossed fewer streams and rivers, too. The trans-Alaska route also was half the length of a line to Canada, so it could be built sooner and at half the cost, according to an article titled “Producers weigh many marketing options” in Petroleum News.

Alaska Gov. Keith Miller and most Alaskans recognized the benefits for Alaska with building an all-Alaska pipeline south and agreed with the proposal to build a terminal in Valdez. The oil companies all got on board with the idea and focused their energies in that direction. They estimated their proposed plan for a 48-inch diameter 800-mile long line that could carry 1.5 million barrels of oil a day at $900 million – the most expensive project ever proposed by private industry at the time. When completed, the final cost actually came in at more than $8 billion due to the delay in its building, the hurried timeframe to finally construct the line and stringent environmental constraints.

Although oil companies were not given the green light to build the pipeline until 1974, they laid much of the groundwork in advance. In October 1968, three major oil companies formed a joint venture to organize, design and plan the pipeline to transport oil from Prudhoe Bay to market as soon as all the legal hurdles had been addressed.

After studying several ideas for getting North Slope crude to market, the oil industry decided that building an 800-mile-long pipeline from Prudhoe Bay to Valdez was the best option.

The new enterprise was called Trans-Alaska Pipeline System, and it included BP, ARCO and Humble Oil. TAPS invited other companies to join them, which led to the inclusion of Mobil Alaska Pipeline Co., Amerada Hess Pipeline Co., Phillips Alaska Pipeline Corp. and Unocal Pipeline Co.

Soon after it formed, TAPS faced a few legal issues that slowed its progress on the pipeline. Congress passed the National Environmental Policy Act in 1969, which required an environmental impact statement for major federal actions that might affect the quality of the human environment. At the same time, Native villages filed suit in federal court to halt construction of a haul road to the North Slope, as it and a pipeline would go across land they claimed was ancestral.

“Stevens Village was located directly in the proposed path of the pipeline,” said Byron Mallott, Alaska’s first Native lieutenant governor, in an interview when he represented First Alaskans Institute. “And the people of Stevens Village said, ‘we can’t let this happen. That until our claims are settled, until we have certainty about what we own and what we don’t own and how this will affect us and our children, we can’t allow this to happen.’”

Three conservation groups – Wilderness Society, Friends of the Earth and the Environmental Defense Fund Inc. – also filed a federal suit asking the U.S. District Court to bar construction of the pipeline until Interior Secretary Walter J. Hickel “complies fully with provisions of the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969,” according to a story in the Anchorage Daily Times on March 28, 1970.

“I saw no recourse,” then-director of the Wilderness Society Stewart Brandborg told a PBS reporter in an interview later. “If the environmental movement hadn’t challenged the pipeline, we would have ended with damage beyond any description.”

A federal judge in Washington, D.C., enjoined both the pipeline and access road in April 1970, ruling neither could be built until the Interior Department heeded the environmental policy act, which required a detailed report on the pipeline’s ecological effects before the department could issue a building permit. Interior Secretary Hickel said even without the court order, his department would block the pipeline until it was proven safe.

Gov.-elect William A. Egan visited Hickel in Washington, D.C., in November 1970 and told an Anchorage reporter that Hickel had said Alaska could expect a “significant development” in the pipeline matter within 10 days. A week later, the night before Thanksgiving, President Richard Nixon called his interior secretary to the White House and fired him on the spot.

Popular opinion speculated Hickel had been on the verge of announcing that Alyeska Pipeline Service Co., organized that year from TAPS to oversee construction of the pipeline, had met federal engineering and environmental stipulations for the project. Some concern was tempered when Acting Interior Secretary Fred Russell extended the 1966 land freeze until June 30, 1971, to allow Congress to settle the Native land claims issue and avoid lengthy battles that might interfere with building the pipeline.

The land on which the line would go was part of the acreage claimed by Alaska’s Native people, so a right of way corridor needed to be settled. Alaska Federation of Natives leaders said they might go to court to protect their rights to the land.

“We don’t want to block the pipeline,” said then-AFN executive director Eben Hopson in a newspaper article on Jan. 2, 1971. “We’re protecting our own rights, which heretofore have not been extinguished by Congress. We’ve got to protect our own rights – it has nothing to do with the pipeline.”

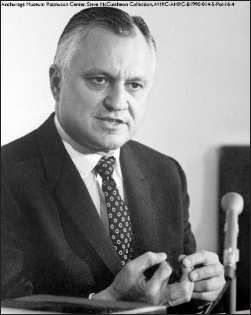

Longtime Alaskan and U.S. Interior Secretary Walter J. Hickel may have been on the verge of giving a green light to the oil companies to build the Trans-Alaska Oil Pipeline when President Richard M. Nixon fired him on Thanksgiving Eve 1970.

Native leaders, like Eben Hopson of Barrow, wanted the Alaska Native land claims issue settled before pipeline construction began.

At that time, Native groups claimed 360 million of Alaska’s 375 million acres. They also sought a monetary settlement of around $500 million and a royalty from any future gas and oil that came out of the ground.

It took another year, but finally all parties came to an agreement on the land claims issue. Congress passed and President Nixon signed the Native Land Claims Settlement Act in December 1971. That cleared the way for federal and state governments to grant essential licenses and permits. Three months later, the Department of Interior released the final environmental impact statement that stressed the need for domestic and Alaska oil. Then Secretary of the Interior Rogers C.B. Morton declared the trans-Alaska oil pipeline to be in the national interest, which allowed the federal injunction against the pipeline to be lifted.

But an appeals court ruled the proposed right of way and special land use permits for the pipeline did not comply with the Mineral Leasing Act. In some places the proposed right of way exceeded the 54-foot width allowed under the act. Congress would need to approve such a right of way, according to a government document titled “History of Trans Alaska Pipeline System.”

So more debate raged over the pipeline for a couple more years while Congress heard from proponents, opponents and environmentalists. And many Alaskans thought the environmentalists from the Lower 48 had gone overboard. Howard Weaver, then a reporter for the Anchorage Daily News, summed up the opinion of many who lived in the Last Frontier.

“We weren’t hungry for, for vast open spaces. We had them,” Weaver told a reporter for PBS in an interview about the pipeline. “You know, that’s what we had plenty of. What we didn’t have plenty of was decent high schools, flush toilets in bush villages. You know, those are nice things, too.”

Environmentalists were worried that the oil industry would dig trenches and bury pipe just like they had all around the world. They believed that approach would harm Alaska’s delicate arctic region where permafrost would be melted by hot-oil pipes and cause massive environmental damage.

Hickel, who served as Alaska’s governor from December 1966 to January 1969, and then U.S. Secretary of the Interior from January 1969 until November 1970, assured all that Alaskans would not allow the oil companies to destroy the pristine environment in the north.

Environmentalists and conservationists wanted to limit development in Alaska’s northern wilderness, but many Alaskans thought they had enough wilderness areas in the vast state and developing the North Slope could be done in an environmentally responsible way.

“… I can guarantee that we will not approve any design based on the old faulty concept of build now and repair later,” Hickel said.

The battle over building the pipeline continued until October 1973 when, in retaliation for American support of Israel in the Yom Kippur War, Arab states declared an embargo on oil shipments to America. That tipped the balance in favor of a new domestic source of oil.

Democratic Sen. Henry Jackson of Washington believed that America was importing too much oil from overseas, which subjected the United States to blackmail.

“… the man in the street wants to ask, ‘well, if we can import it from the Middle East and every other place in the world that’s substantially insecure, why can’t we import it from Alaska?’” Jackson asked in a television interview at the time.

There’s no doubt the oil embargo put pressure on politicians to move the pipeline project forward, but oil companies also were more than ready to begin building it. They had spent billions developing Prudhoe Bay and planning for the pipeline. The industry said it was losing $22 million a day in revenue while the oil sat in the ground.

Nixon signed the Trans-Alaska Pipeline Authorization Act on Nov. 16, 1973, after Vice President Spiro Agnew cast a vote for the act and broke a deadlock of 49 to 49 in the Senate.

The act was intended “to insure that, because of … the national interest in early delivery of North Slope oil to domestic markets, the trans-Alaska oil pipeline be constructed promptly without further administrative or judicial delay or impediment.”

The act directed Secretary of the Interior Morton to authorize the federal right of way for the pipeline, which he signed on Jan. 23, 1974. The state followed suit four months later, and issued its right of way lease on May 3.

Now it was time to build a pipeline through one of the most remote and challenging regions in the world.

Workers Blaze Haul Road

Alyeska Pipeline Service Co. needed a road on which to haul supplies and equipment to build the trans-Alaska oil pipeline. So, in anticipation of rights of way being granted, it had tons of road-building equipment and camp units placed along the proposed route in 1969-1970. The road would start at the Yukon River – at the end of the 53-mile Elliott Highway from Fairbanks to Livengood – and go about 360 miles north to Prudhoe Bay. Ice roads were built across the Yukon River each winter to keep supplies moving.

Although the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act passed in 1971, Congress didn’t give the OK to the rights of way permit until the end of 1973. As soon as the permit was received, construction of the road went into high gear.

From late January to mid-April 1974, hundreds of workers moved 34,000 tons of material and machinery into northern Alaska via airplanes and trucks. Five new camps were constructed and seven closed camps were opened. Workers built temporary airstrips on snow and ice, which would be replaced by permanent gravel strips in the spring.

They actually started the haul road in April. With more than 3,400 workers battling temperatures that dipped to minus 68 degrees Fahrenheit, crews built north and south simultaneously from eight sections until they all connected, according to an article titled “Fast and furious construction” in Petroleum News. A squadron of more than 60 aircraft, from fixed-wing transports to helicopters, carried supplies across the northern skies to help with the road-building project. Industry records show more than 127,000 flights were logged, an average of 700 flights per day, which carried 160,000 tons of material and 8.5 million gallons of fuel to power construction equipment and camps.

Trucks then carried more than 31 million cubic yards of rock to bring the 28-foot-wide haul road up to state secondary road standards. Completed on Sept. 29, 1974, it took 154 days to build that road through the wilderness – although the $30 million permanent 2,295-foot bridge across the Yukon River wasn’t finished until 1975.

“The 3-million-manhour-single-summer project was unprecedented in Alaska history,” a Petroleum News article stated, and it cost $185 million.

The state renamed the North Slope Haul Road in 1981 for James B. Dalton, a native-born Alaskan and engineer who supervised construction of the Distant Early Warning Line in Alaska during the 1950s. The system of radar stations, which stretched from the Arctic regions of Alaska and Canada to the Faroe Islands, Greenland and Iceland, was set up to detect incoming Soviet bombers during the Cold War era.

Dalton’s father, Jack, was an early Alaska pioneer, explorer and adventurer who had established a successful toll road through Southeast Alaska to the gold fields during the Klondike gold rush days.

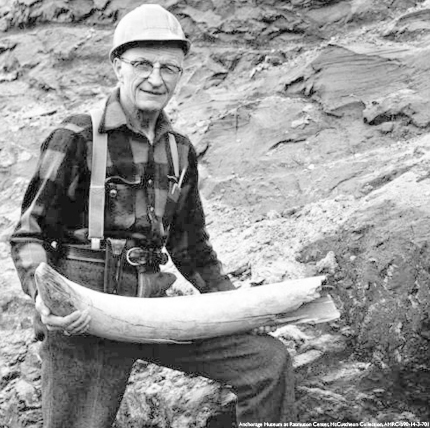

Road construction crews found more than rocks, dirt and frozen tundra while building the Haul Road. Foreman Pete Peterson holds a mastodon tusk they found in a road cut opposite Five Mile Camp in Alaska’s Interior on April 28, 1974.

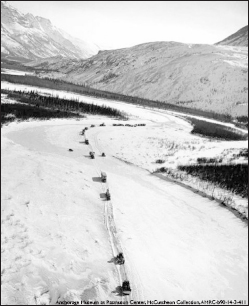

Construction crews carved a rough road from just outside of Fairbanks to Prudhoe Bay in order to haul supplies for the pipeline through hundreds of miles in Alaska’s wilderness. This photo shows the Haul Road dropping from Atigun Pass north to Atigun Valley in the Brooks Range. It later was renamed the Dalton Highway.

Culverts were installed to provide crossroad drainage along the Haul Road, as seen in this photograph near Old Man Camp south of the Arctic Circle near Kanuti National Wildlife Refuge.

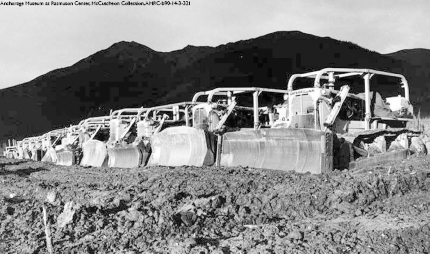

Once Congress approved the construction of the trans-Alaska oil pipeline, the oil companies began frantically getting equipment and supplies up the Haul Road to Prudhoe Bay. This line of Caterpillar bulldozers at Galbraith Lake in the Brooks Range were hauled north at a cost of $1.50 per pound, according to information with the photograph. That comes to about $200,000 each.

A convoy of trucks travels along the frozen John River from Bettles just before completion of the Haul Road into Alaska’s Interior on March 29, 1974.

Chaining the trucks so they could cross mountainous regions along the Haul Road was not an easy task, as seen in this photo taken near Wickersham Dome on April 15, 1975.

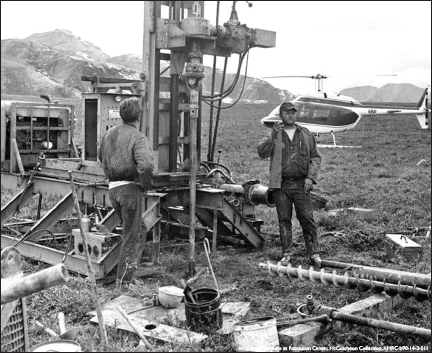

Before the oil industry was given the go-ahead to build the trans-Alaska oil pipeline, it spent several years testing the soil along the route it proposed for the construction. This photo shows a drilling crew testing soil at Chandalar Shelf just south of Atigun Pass, the highest point on the Haul Road.