32

A GREAT RACE IS BORN

The two legendary visionaries who conceived the 1,049-mile race from Anchorage to Nome hardly could have imagined the success and changes that would happen during the next several decades of the Last Great Race.

In 1964, a history buff who lived in Wasilla had an idea. Dorothy Page, secretary of the Aurora Dog Mushers Club, saw that snowmachines were taking the place of dog teams and mushing. She thought a sled dog race on the historic Iditarod Trail – which originally began in Seward during the gold rush days and stretched to Knik – through the gold camp of Iditarod and eventually to Nome, might revitalize a longtime Alaska tradition. But Page knew that she would have to find a musher to share her dream before it could become reality.

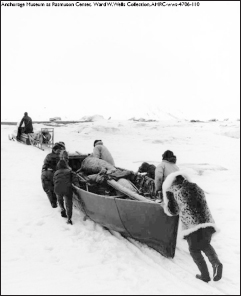

Horsepower replaced dog power during the 1960s, as seen by this snowmachine pulling a walrus skin boat up the beach at Gambell on St. Lawrence Island.

Good sled dogs were worth their weight in gold when miners first began mushing along the Iditarod Trail. These pups sold for $100 each in 1900 – nearly $2,500 in 2015 dollars.

She endured comments such as “Are you crazy?” for two years, until she talked to Joe Redington Sr. during a break at the Willow Winter Carnival sled dog races in 1966. Page explained her idea to the veteran musher, who had traveled over sections of the historic Iditarod Trail while homesteading near Flat Horn Lake.

His response — “I think that’s a great idea!” — has been echoed by hundreds of mushers from all parts of Alaska, the Lower 48 and foreign countries ever since.

Fifty-eight mushers signed up to compete for $25,000 in prize money for the 1967 inaugural race. Since only nine miles of the trail had been cleared, the race ran from Knik to Big Lake on Saturday, and from Big Lake to Knik on Sunday, for a total of 56 miles. Isaac Okleasik, an Eskimo from Teller on the Seward Peninsula north of Nome, won the Iditarod Centennial Race.

Due to a lack of snow in 1968, a lack of money in 1969 and a lack of interest from 1970 to 1972, the race was put on hold. But behind the scenes work continued as volunteers cleared the brush from both the Nome and Knik ends of the trail.

Finally, on March 3, 1973, amid the cheers of hundreds of well-wishers, 34 mushers left Anchorage headed for Nome in pursuit of not only a dream, but also $50,000 in prize money pledged by Redington. They raced across a route that generally followed the trail of a group of mushers who sped diphtheria serum from Anchorage to Nome in 1925.

Dick Wilmarth, a hard-working gold miner and trapper from the Interior village of Red Devil, later told reporters he heard some of his competitors talking about quitting about halfway to Nome.

The musher said he was camped out in a cabin near Galena when a few other mushers came inside during the middle of the night and said they wanted to talk to him. They all were getting cold, as the temperatures had dipped to the 50-below-zero mark, and wanted to quit the race. But they wanted the decision to be unanimous, they told him.

Wilmarth was not a quitter. He did not want to be a part of that conversation.

Joe Redington Sr., his son and others cut the Iditarod Trail from Knik to Nome prior to the 1973 race.

“I told them, ‘I’m going to go to Nome,’” he told Associated Press writer Mary Pemberton in 2001.

The 31-year-old hurried outside, hooked up his dog team and headed down the Yukon River.

The determined musher, who snared beaver for food along the trail, said people along the Yukon did not want to share food or fish with him.

“Those guys on the Yukon wouldn’t give me any food,” he said in a newspaper interview later. “They were rooting for their own guys.”

Wilmarth crossed the finish line first and collected $12,000 in prize money. It took him 20 days, 49 minutes and 41 seconds to travel the old winter trail that mushers hadn’t used for almost 45 years.

He had assembled his team a few months prior to the race, rounding up dogs from villages on the Kuskokwim River. He said he traded his .22-caliber rifle for a snowmachine and then traded the snowmachine for five dogs.

Joe Redington Sr., holding the trophy, and Orvile Lake, holding the microphone, congratulate Dick Wilmarth, center, winner of the 1973 Iditarod race in Nome.

Along the trail he and his friend, renowned sprint dog musher George Attla, hopped onto snowshoes to clear a path for the dog teams after Finger Lake, where there was no trail. Attla followed Wilmarth into Nome to clench fourth place in the historic race.

John Schultz crossed the finish line more than 12 days after Wilmarth. About one-third of the 34 starters dropped out along the way.

Alternating every year between the southern route and the northern route, the current trails cross the Alaska Range, Kuskokwim Mountains, Nulato Hills and more than 200 miles along the mighty Yukon River. Once the mushers take off from Knik, they leave civilization behind and only have small towns and villages such as Skwentna, Nikolai, Ophir and Unalakleet to break the monotony of traveling in bone-chilling cold until they reach the historic gold rush town of Nome, perched on the shores of the Bering Sea.

By the early 1980s, the prize money had doubled and the trail time had dropped almost in half.