MASS MURDER IN THE NORTH

36

MASSAGE PARLOR MURDERS

Money. Power. Sex. These were the elements involved in a string of killings connected to lucrative massage parlor and nightclub businesses flourishing in Anchorage during the mid-1970s.

Thousands of pipeline workers were arriving in town with wads of cash to spend – and massage parlors sprang up to help them spend it. The seedy storefronts offered relaxation and companionship from long, lonely hours on the North Slope. The Body Shop Massage in Spenard enticed customers with ads like “come on in and get your batteries checked and charged.”

Prices posted on rate schedules ranged from $5 for an actual massage to $100 for a “date.” Police considered most of the establishments to be fronts for prostitution, and it was common knowledge that anything could be had for a price at a massage parlor, according to newspaper accounts at the time.

The city had a law that mandated masseuses in the parlors be “of good moral character” and have no record of “pimping, pandering, prostitution, solicitation, lewd or lascivious acts with a child, larceny, robbery, assault with a deadly weapon or other similar crimes.” But in Spenard, outside the city limits, no such laws existed.

With so much money changing hands, it’s not surprising that many wanted a piece of the massage parlors’ lucrative pie. Even the Internal Revenue Service and Alaska politicians tried to figure out ways to share in the wealth.

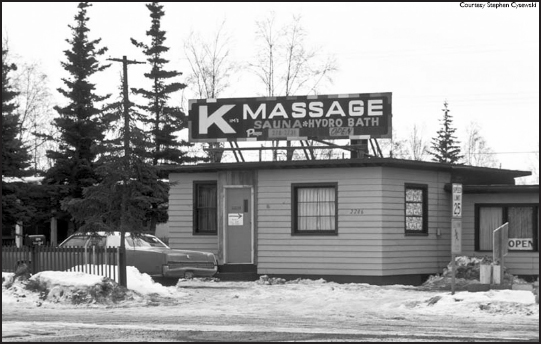

Kim’s Massage was one of many establishments that promised pipeline workers a good time in Anchorage during the 1960s and 1970s.

“Uncle Sam wants his share,” a high-ranking official with the IRS said in 1973. He figured the government should tax the moneymaking massage business, which numbered 26 parlors in Anchorage by the mid-1970s.

The Alaska Legislature entertained a bill in 1975 calling for the legalization and regulation of prostitution to get tax revenue. It never passed out of committee.

The Anchorage Assembly appointed a 12-man commission to look at the possibility of legalizing and taxing the massage business. At a final vote, however, the assembly turned down the commission’s plan.

Others took less noble routes to get their hands on all that cash – including murder. And while Alaskans saw several murders during the 1970s, none piqued the interest of the public more than what newspapers dubbed the “Massage Parlor Murders.”

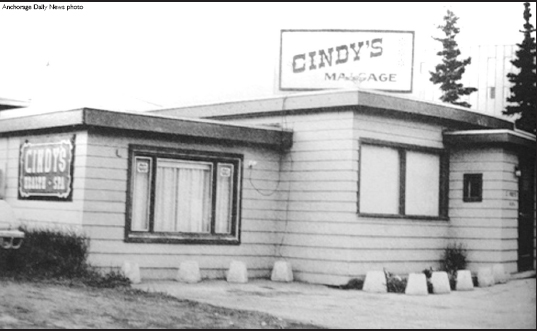

It began in November 1972 when Ferris Rezk Jr., owner of Cindy’s Massage Parlor in Spenard, was found shot to death in his 1968 blue Plymouth a few blocks from the Kit Kat Club. Anchorage police arrested Clarence Wesley Ladd the next day and charged him with first-degree murder.

Ladd had moved to Anchorage that year after spending time in Cordova. He was a regular at the Kit Kat Club and wanted to get into the massage parlor business. He saw how a small grubstake could yield high profits.

Police believed that Ladd had shot the young Rezk, also known as a small-time pimp and heroin dealer, over a deal gone wrong to purchase Cindy’s. Newspapers reported Rezk wanted $10,000 for his business, which was rumored to average weekly receipts of $5,000. Ladd had made a down payment of $4,000 after checking out the club at West 29th Avenue, and he later made one $3,000 payment.

The state asserted Ladd murdered Rezk because he did not have the money for that final $3,000 payment. Killing Resk would solve that problem.

A series of murders surrounding Cindy’s Massage parlor rocked Anchorage during the early 1970s.

A standing-room-only crowd filled the courtroom when Ladd’s trial began in late spring 1973 to hear Rezk’s girlfriend and business partner testify. Patricia “Cindy” Bennett told the court that she saw Ladd shoot Rezk because the “organization wanted him dead,” according to an article recounting the events featured in the Anchorage Times on Dec. 23, 1979.

Attorney Edgar Paul Boyko represented Ladd. Well-known for winning impossible cases, Boyko told the court that Rezk had been targeted by a criminal organization that wanted to set up a protection racket involving all the massage parlors in town. He said a mysterious hit man for the “Organization” had killed Rezk. The gun used in the murder had ended up in Ladd’s hands when he struggled with the killer, who then got away.

Boyko grilled prosecution witness John F. “Johnny” Rich Jr. in an effort to give Ladd’s defense credibility. He wanted the jurors to think that Rich was a player in the rumored Organization.

Rich, a well-known figure in Anchorage’s underworld, had taken over the lease of Cindy’s after Rezk’s murder. He renamed the parlor New Cindy’s Health Spa & Massage. A longtime Anchorage resident with several misdemeanor gambling charges, Rich also owned the 736 Club and Alaska Firearms Distributors.

As a witness for the prosecution, Rich testified that Ladd had come to him for a loan of $3,000 prior to the murder. He said he denied Ladd’s request. Rich also said Ladd’s girlfriend had called him after the murder to ask what he knew about the Organization.

Boyko cross-examined Rich for four hours in an effort to convince the jury that Rich was a nefarious character. It was an easy sell at the time – many people in Anchorage believed criminals and the Mob were running their town.

The defense strategy worked. After a month-long trial, the 12-woman jury found Ladd innocent.

Within a few months, Rich disappeared. The last time anyone saw him was on Aug. 22 sitting in his brown 1971 Cadillac near Pacific Auction on Old Seward Highway.

A few days after his disappearance, Ladd and attorney Duncan Webb appeared at Cindy’s and claimed Rich had given them power of attorney to take possession of the parlor and other properties, according to the Anchorage Times.

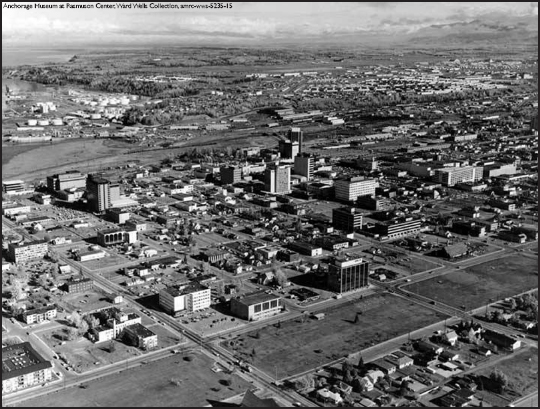

Many massage parlors and adult entertainment businesses made their way to Anchorage and were well-entrenched in downtown and Spenard during the early 1970s.

The attempted takeover failed, and police were notified of the dispute.

Then someone shot the wife and son of nightclub owner Jimmy Sumpter while they slept in their Anchorage home on Nov. 26. The house was set afire to cover the murders. Sumpter’s 16-year-old daughter escaped out a window and ran to a neighbor’s house to get help.

Sumpter, owner of the Kit Kat Club and Sportsman Too, was out of the house picking up receipts from his clubs at the time of the murders. He arrived home in time to see firemen battling the blaze at his house.

Witnesses told police they had seen a car speeding away from the Sumpter home. The next day, authorities questioned a man named Gary Zeiger, whose car matched the description given at the scene.

Zeiger, who recently had been acquitted of murdering a young Anchorage woman, must have given the police some valuable information, because he was offered protective custody after posting bond. Zeiger declined the offer.

The next day his body was found dumped in the Potter Marsh area. He’d been killed with a single shotgun blast to his chest.

Rich’s body was found on Dec. 20. Virginia Pinnick, Ladd’s girlfriend, led state troopers to a shallow grave in the Jonesville coalmine area about 17 miles north of Palmer on the Glenn Highway. Rich had been shot twice.

The police began to think all these murders were connected. They believed Zeiger had a hand in both the Rich and Sumpter killings, and Zeiger and Pinnick were known associates of Wesley Ladd.

An indictment was handed down for Ladd and his friend, Guy Benny Eugene Ramey, in March 1974. Court records showed that Ramey had taken a flight to Seattle under the name John Rich the night of Rich’s disappearance.

Ladd and Ramey were charged with first-degree murder and kidnapping of Rich. Two weeks after his arraignment, Ramey, 19, pleaded guilty to the kidnapping. The judge sentenced him to 10 years in jail, and Ramey agreed to testify against Ladd.

Pinnick was charged with first-degree murder the next month. The secret indictment connected the 19-year-old woman to Rich’s killing. Her involvement was explained a few months later during the trial of Ladd’s attorney, Webb, who had been charged with being an accessory after the fact and compounding a crime.

Webb’s trial, held that July, happened before Ladd’s because attorneys for Ladd wanted a change of venue for their client’s trial. They requested it be moved to Kodiak, where newspaper coverage may not have tainted the jury pool.

During Webb’s trial, prosecutors laid out their theory of what happened to Johnny Rich. They alleged that Ramey, Ladd and Zeiger had kidnapped Rich, driven him to Pinnick’s Eagle River cabin and forced him to sign power of attorney papers for Cindy’s.

The state asserted that Ladd shot Rich. Then Zeiger shot him again and took Rich’s body to that abandoned mine near Palmer and buried it. Ramey boarded a plane for Seattle under the name John Rich in an effort to show that Rich still was alive.

Webb, who earlier had told investigators that Rich signed those documents in front of him and he then had taken Rich to the airport himself, retracted his statement. Webb told the court he’d been forced to tell police that Rich had gone to Seattle to deal with some business affairs. He said he did so because he was afraid for his life.

After closing arguments, the jury retired to weigh the evidence. But members of the jury could not come to an agreement, and Webb’s first trial ended in a hung jury. He was convicted the next year, however, and disbarred from practice as an attorney in 1979.

After a two-week trial in Kodiak, a jury found Ladd guilty of the kidnapping and murder of Rich. Superior Court Judge James Fitzgerald sentenced Ladd to life in prison and called the Rich killing a “planned execution motivated by revenge.”

Attorney Duncan Webb lied when he told police he dropped Johnny Rich Jr. at the Anchorage airport, seen here in the 1970s, to catch a flight to Seattle. An associate, Gary Zeigler, had impersonated Rich on that flight south.

Anchorage sprawled in 1973 from downtown toward Spenard and the mountains.

Rich’s daughter, Kim, a teen at the time of these murders, later researched this episode in Anchorage’s past and wrote a book about it and her life with her father titled “Johnny’s Girl.” It later was made into a movie.

In the late 1970s, the Anchorage Assembly decided the time had come to crack down on the massage industry. After a hard-fought battle between parlor owners, municipal officials and citizens, a new ordinance passed in 1978. It required massage parlor operators to apply for licenses as physical culture studios.

That ordinance did not help protect the never-ending stream of young women who came north to work in these establishments, however. And soon strippers, topless dancers and prostitutes began disappearing.