THE HELICOPTER flew in low across open countryside, less than a hundred feet above the ground. The side door had been removed earlier in the day so the archaeologist could take photographs. The slipstream heavily buffeted him as he held his camera nervously in the backseat, leaning out to study the farmland slipping away below his feet. Barry Raftery, professor of archaeology at University College, Dublin, was riding a helicopter for the first time in his life, searching for eskers, the long gravel ridges left behind by the last Ice Age. The ridges show up best from the air, like great snakes slithering across the midlands of Ireland. They were the superhighways of Ireland throughout Irish prehistory, the best way to cross a forested land if you could not travel by boat on the rivers and lakes. "You'd get lost pretty fast among the trees," Barry said, "but gravel ridges were almost free of vegetation cover so they made good route-ways. You could see where you were going. You didn't get lost if you were on an esker."

Unfortunately Barry was lost. For thousands of years the Irish navigated their way cross-country along the eskers, but such ancient route-ways do not appear on modern maps. He remembered seeing one from a train window between Dublin and Galway, so the pilot was flying west along the railroad track, watching for the quarries that are often sited on these vast gravel deposits formed by Ice Age glaciers a hundred thousand years ago.

"Is that a gravel truck?" Barry's voice was hopeful, anxious for the search to succeed so he could return safely to ground level. Archaeologists are happier with feet planted firmly on the ground where their evidence is usually found, but the opportunity to see and photograph eskers from the air was enough to overcome Barry's initial apprehension. The pilot swung the jet-ranger around to hover briefly over a heavily loaded truck before following the road back the way the truck had come. Within seconds a quarry came in sight, an ugly scar of gray and white gravel slicing deep into the soft green of an Irish hillside. Barry had found his esker, a narrow ridge rising thirty feet above the surrounding countryside and snaking away for nearly a mile before losing itself in a distant pine forest. In the quarry, diggers sliced into the hillside while trucks belched diesel fumes as they roared off to deliver gravel to building sites across the country.

The pilot brought the helicopter in to land on the top of the ridge, and Barry unbuckled his harness and stepped thankfully to the ground. It was like standing on the back of a great snake; one St. Patrick might have missed in his mythical expulsion of all the snakes from Ireland. The ridge may have been part of the famous Sit Asaíl, or Way of the Donkey, whose name survived into Christian times. "Everyone used these eskers," Barry said. "Kings, poets, warriors, priests. Imagine chariots, carts, wagons bringing people and goods, cattle being driven, family groups on their way to a solstice celebration at one of the great royal sites, like Tara in the east or Cruachan in the west."

The eskers were first used as roadways back in the Stone Age, when Ireland's early farmers raised great burial mounds as memorials to their ancestral gods, but Barry was speaking of a later time, around 200 B.C. during the Iron Age. He is one of Ireland's leading archaeologists, steeped in ancient Ireland before he could walk since his father was an archaeologist as well. Barry specializes in the Iron Age, those nine hundred years between the sixth century B.C. and the coming of Christianity to Ireland in the fifth century A.D., but he loves all periods of Irish prehistory, right back to the very beginning.

The prehistory of any country is what happened before the advent of writing. Literacy did not develop in Ireland until the coming of Christianity in the fifth century A.D. As people first arrived at least eight thousand years earlier, there are millennia that are known only through myth, legend, and the archaeological evidence left in the ground.

The gravel eskers are woven into the fabric of Irish history. Formed when great glaciers scoured the bedrock of Ireland during the last Ice Age, they are only now succumbing to the industrial boom of twenty-first century Ireland, their gravel part of new concrete and steel buildings rising in every modern Irish city. They were still roadways in early Christian times when monastic scribes first wrote Ireland's history and invented fantastic stories about their country's pre-Christian Celtic past. They felt the feet of Neolithic farmers who five thousand years earlier were clearing forests to plant their crops and raise their cattle. Ten thousand years ago they were crossed by wolf and bear when the land stood empty, awaiting the first hunter-gatherer immigrants to cross from Britain. For Barry Raftery, an archaeologist who has spent his life investigating the past, the eskers symbolize the continuity of Irish history; with every age and every generation shaped and rooted in the landscape where they lived.

In the beginning there was a lot of ice. Until the last Ice Age ended around twelve thousand years ago, there is no evidence of human occupation in Ireland, although early humans were present as far north as southeastern England half a million years ago. The last Ice Age put Ireland in the freezer around 115,000 B.C. As the weather turned colder, ice caps formed around the high mountain peaks of Donegal and Antrim in the north, Wicklow in the east, and perhaps Cork and Kerry in the south. During the next few thousand years, glaciers moved out from these mountain ice caps to meet and join other glaciers from Scotland and Iceland, inching south until Ireland, like much of northern Europe, was locked in a thick prison of ice.

Elsewhere in Europe, beyond the range of the glaciers, people used fire to keep warm, pressed their handprints on rock to create the first cave-paintings, and developed new tools and weapons for the hunt. But in Ireland, cold winds howled across empty snow-fields and ice sheets thousands of feet thick ground the country's bedrock into the gravel later left behind as eskers.

No Ice Age is continuous. There were periods of warmth when the glaciers retreated for a while. So much water was locked up in the ice that sea levels were as much as forty feet lower than today. Land bridges linked Ireland with Britain, Britain with Europe, and Russia with Alaska. Across the Atlantic, a temporary warming permitted the first people to walk into America from Asia before the cold returned in 30,000 B.C. and ice again blocked the way south. But by 14,000 B.C. the last Ice Age was near its end, glaciers were in retreat, and the Bering land bridge from Asia to America was permanently open. The ancestors of today's Native Americans crossed around 12,000 B.C. and spread south to reach the farthest tip of South America within two thousand years. Ireland too had ice-free areas during the Ice Age, south of a line that runs from Waterford in the east to the Dingle peninsula in the west. People could have lived there, although no trace has ever been found. But from 10,000 B.C., Ireland was open for settlement.

Archaeologists like the past to fit into neat categories so the Stone Age, which refers to a pre-metal age when people used stone to make tools and weapons, is divided into three periods. The Paleolithic period—or Old Stone Age—is irrelevant to Irish history since it falls during the Ice Age when Ireland was uninhabited. The Mesolithic period—or Middle Stone Age—began in Ireland after 10,000 B.C., when people first arrived in the country and ended around 4500 B.C. with the coming of the first farmers. The Neolithic period—or New Stone Age—covers the time of these first farmers until a new metal technology arrived in Ireland around 2400 B.C. at the start of the Bronze Age. Such divisions are useful to archaeologists but mean nothing to people living at the time. Stone tools were used long after 2400 B.C., and bronze was being smelted and forged into Christian times. So we should not imagine a tribal chief, having just purchased an iron sword from a traveling smith, shaking his wife awake one morning with the news, "Guess what, dear? We're in the Iron Age."

The first people to arrive in Ireland found a land covered in forests of pine, oak, elm, and hazel. Bogs had already begun to form, covering only a small fraction of the 14 percent of Ireland they covered in the twentieth century. The first arrivals were already sophisticated hunters with a superb technology for producing weapons and tools out of chipped flint. They used bows and arrows, knew how to make nets and set fish traps, and were as intelligent in their own way as people are today. We can imagine these first immigrants walking through the wooded countryside in small family groups around 9000 B.C., leaving southwest Scotland to enter Ireland north of Belfast, up by Ballycastle in County Antrim. Much of the archaeological evidence from the Mesolithic period is in the northeast, where Ireland and Scotland are less than fifteen miles apart and where there are rich beds of flint, the necessary raw material for making stone knives and axe-heads.

Scholars argue about whether Ireland and Britain were still joined by a land bridge at this time. As the ice began melting, sea levels began to rise. The land bridge could have been cut much earlier, in which case the first Irish might have come by boat. We have no way of knowing. It is a popular misconception that Ireland has been subject to many different invasions throughout its history, each in their turn sweeping ashore to seize the land. The Fir Bolg, the Túatha Dé Danann, the Sons of Míl—better known as the Celts—have all left their mark on Ireland's mythology. But archaeology shows no indication of large-scale movements of people into Ireland from overseas; immigrants trickled in over hundreds or thousands of years. It was the same in Mesolithic times; the first immigrants arrived family by family. The population of Mesolithic Ireland was not likely more than a few thousand people, living in small family tribes, since a hunting and gathering lifestyle does not encourage large populations.

In the 1970s archaeologist Peter Woodman excavated a Mesolithic site at Mount Sandel, in County Derry, which has been carbon-dated to around 7000 B.C. This was a rare find, the first clear evidence of how people lived at the dawn of Irish prehistory. Finding evidence of Mesolithic occupation is often a matter of luck. Most sites have been plowed under, covered by water as sea levels continued to rise, or have simply vanished without a trace. Not much is left after nine thousand years, although two hundred sites have been found, the majority in the northeast of Ireland. They are all near water, either along the coast or beside inland lakes and rivers. Hunter-gatherers in early Ireland lived in round huts made of tree branches and animal skins, easy to assemble and light enough to carry when people moved from place to place. They were like the tepees of Native Americans or the yurts of Mongolian herdsmen today, all nomadic peoples.

Although the Mount Sandel site has been dated to 7000 B.C., people may have been living in Ireland thousands of years earlier. The excavated area at Mount Sandel covers more than eight hundred square yards and shows frequent use over many centuries. These are the first Irish people whose life we can describe. What they left behind provides tantalizing clues to how they lived. There was charcoal from hearths, and signs of ten circular huts, each about twenty feet in diameter. There was even an industrial area where flints were worked into axe-heads and other tools. And there were fragments of burned bones, shells, and nuts. Mount Sandel was probably a base camp for a small family group of no more than ten people. Organic remains found on site give us a snapshot of their life. They ate a lot of fish, mostly salmon and eel, along with pig, hare, and wild birds; there is no sign of deer bones, so perhaps Ireland's red deer were not around at the time. They collected hazelnuts, an excellent source of protein, while water lily and wild pear seeds show that fruit and vegetables were also a part of their diet. In Ireland a wide range of food was available, so it was probably a comfortable and healthy life, staying near the coast in spring, moving inland along the rivers and lakes to take advantage of the summer migrations of salmon and eel. Fall and winter could be spent on higher ground, collecting hazelnuts and butchering young pigs to supplement their diet. Other European peoples had domesticated dogs by this time, and fragments of dog or wolf bones were found at Mount Sandel. It is possible the ancestor of today's Irish wolfhound loped along the forest trails beside these first hunter-gatherers, ears pricked and nose down as it followed a trail of tasty wild pig.

Burned stones found near the camp are reminiscent of the fulacht fiadh, or burned mounds of the Bronze Age more than six thousand years later, where stones were heated in a fire before being raked into a stone or wood-lined pit full of water. More than 4,500 have been found across the country; they are Ireland's most common prehistoric monuments. Bronze Age fulacht fiadh have been tested many times; fire-heated stones bring the water to the boil and keep it boiling with the addition of fresh stones for hours at a time—long enough to cook an entire wild boar. There are no pits like this at Mount Sandel, but fire-burned stones suggest a similar style of cooking. Hot stones could have been placed inside leather containers to heat liquids and make a form of soup or gruel.

If Mount Sandel started off as a winter camp, so many different foods have been found there that it was certainly occupied at other times of the year. An extended family band of twenty-five, including children, is considered the ideal size for a hunter-gatherer tribe; any larger and they exhaust the resources in their immediate territory; any smaller and their breeding group is too small to survive for many generations. If only ten people lived at Mount Sandel, the site may have been part of a larger community with other sites in the area. Hunters and food-gatherers may have traveled among smaller temporary camps set up at different times of the year to take advantage of seasonal changes in the food supply.

Elsewhere in the world in 7000 B.C., Jericho and other small farming communities in the Middle East and Pakistan were beginning to develop into the world's first towns. Jericho's first houses were circular, like the simple skin and branch huts at Mount Sandel, reproducing in mud-brick the shapes of the tents used by their earlier nomadic hunting ancestors. Jericho and other new communities were growing up around the cultivation of cereal crops like wheat and barley and the raising of domestic animals. It would be another two thousand years before this farming revolution reached Ireland. In the meantime, much was happening.

If land bridges existed between Ireland and Britain at the beginning of the Mesolithic period, they were cut before 6000 B.C. when the warming melted the last of the glaciers and the ocean reached levels perhaps twenty-five feet higher than today, a sea rise of possibly seventy feet since the Ice Age. The waters would slowly recede to present levels as polar ice caps grew larger, but 6000 B.C. was an age of inundation. In places the land rose too. Like a sponge pressed flat by a heavy rock, Ireland had been compressed under the weight of ice for nearly a hundred thousand years. Once weight is removed, a sponge will gradually expand; Ireland was rising, in placesas much as fifteen feet. Two opposite reactions, sea rise and land lift, changed and twisted Ireland's coast, drowning some areas while lifting others clear of the advancing waves.

By 6000 B.C. any land bridge was cut between Britain and Europe. Isolated for the first time, populations were beginning to develop individual characteristics, depending on the climate and geography where they lived. In Ireland, archaeology shows that Mesolithic societies developed differently from similar communities in Britain. Through most of prehistory, up to the time of the Roman Empire, the Irish shared a measure of common character and culture with people across the entire western seaboard of Europe. But for a long period of time during the Mesolithic Age, archaeologists believe there was little or no interaction between people on either side of the Irish Sea. Perhaps sea rise and coastal flooding made the shoreline too dangerous. Perhaps sailing was a skill either forgotten or not yet learned by these hunter-gatherers who lived on lands around a storm-tossed Irish Sea.

While sea levels were reaching these record levels, farming towns further south began to develop on the fertile flood plains of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in present-day Iraq. Within two thousand years these communities were absorbed into Sumer, which went on to develop the world's earliest urban civilization and the world's first written language. The Sumerian epic of Gilgamesh includes the story of a great flood which drowns most of mankind. The Hebrews adopted this Sumerian legend when they collected together the stories that became the Book of Genesis. Oral storytelling traditions can span thousands of years, so the Christian Bible probably records the memory of an event eight thousand years ago, when fertile lands around the world were inundated by the sea and the islands of Britain and Ireland far to the north were finally cut off from the great continental landmass of Europe.

People may have been using boats in one form or another since at least the last Ice Age. If the land bridge between Ireland and Scotland was cut before the beginning of the Mesolithic period, then the first Irish certainly arrived by boat. One of the earliest known forms is the coracle. They were still being used on Irish rivers into the twentieth century, and their use goes back to Neolithic times, probably earlier. The coracle is a simple framework of light branches, lashed together and covered with animal skins. It looks like a large bowl, an upside-down version of the huts used by Ireland's Mesolithic inhabitants. We can never know how human innovations first occurred, but coracles resemble Mesolithic huts so much so that it is tempting to imagine an early hunter sheltering one day from the gale-force winds so common in Ireland. He might have watched in amazement as his hut was picked up, overturned, and sent spinning out over a lake to land upside-down, bobbing gently on the water. "Hmmm!" our imaginary hunter might have said, "That gives me an idea." And so the coracle was born.

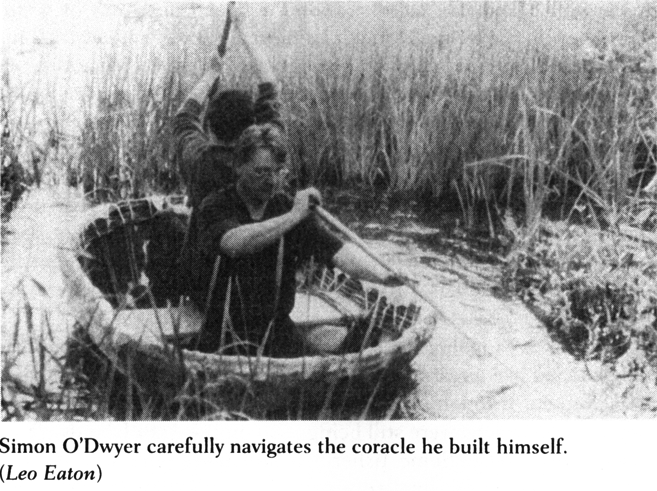

The Irish also used dugout canoes, but the hide-covered coracle and its oceangoing cousin, the currach, were plying the rivers, lakes, and seaways around the Irish coast from earliest times. Simon O'Dwyer is a traditional Irish musician who has studied and re-created musical instruments from Irish prehistory, including bird-bone flutes that may have been played by these Mesolithic hunter-gatherers. He has also built his own coracle in traditional style with a cowhide lashed around a light framework of willow branches. Coracles are difficult to navigate until you get the hang of them, as Simon quickly discovered the first time he launched it on a lake in Connemara and took the single paddle to move it away from the dock. Coracles are circular and buoyant as corks, so one wrongly applied paddle stroke sends them spinning like a top. Eventually he got the hang of it, sitting in the middle and leaning forward so that the coracle tipped like a lopsided teacup. To go forward, one must paddle from the front, pushing the water back under the hull. Handled correctly, coracles are fast and dependable little craft, difficult to sink but easy to capsize if you make a mistake.

Their oceangoing big brother, the currach, is longer and thinner, shaped like a real boat rather than a floating teacup, with bows raised to cut through breaking seas. In the early twentieth century, forty-foot currachs were still being used on the Aran Islands off Ireland's west coast. Some fishermen still prefer them to wooden-planked boats, and smaller versions are raced each year during Sports Day on Inismor, Aran's largest island. Canvas has replaced animal skins while tar takes the place of animal fat to keep them waterproof, but a Stone Age fisherman would feel right at home in a modern currach. Such boats probably brought the first farmers to Ireland around 4500 B.C.

Ireland had no sheep or cattle in Mesolithic times. No ancestral wheat or barley grew wild on Irish hillsides. Everything needed for a farming existence had to be carried by boat. The first Neolithic farmers may have been new immigrants, spreading northward from Europe into Britain and across to Ireland, seeking new opportunities in an emptier land, but perhaps agricultural knowledge was brought back by Mesolithic traders or fishermen from Ireland who traveled overseas and caught a glimpse of the future in communities in Britain or Europe where cattle were raised and cereal crops harvested. All the great innovations of prehistoric Ireland— farming, building great stone burial tombs, bronze and iron technology—arrived gradually over many generations, carried either by new arrivals or by native Irish who had sailed to other lands and were returning home, eager to show friends and relations what they had learned in foreign parts. Irish people have always had a tendency to wander abroad, a characteristic well documented over the past two thousand years. Why should they have been any different in Mesolithic or Neolithic times?

It is misleading to think of such huge changes in society in respect to more recent examples, such as America's pioneer farmers moving west to displace Native American hunter-gatherers from their land. This involved much greater numbers of people. With Ireland's Mesolithic population no more than a few thousand, huge areas of the country would have been uninhabited. Although farming would eventually take over as the dominant Irish lifestyle, farmers and hunter-gatherers could have lived side-by-side for a long period of time. So cattle first brought across the sea in skin-covered boats became the original breeding stock for herds that grew into the primary measure of wealth in Ireland for the next six thousand years.

The Dingle peninsula is in the far southwest of Ireland. It juts out into the Atlantic like a great finger, its spine of mountains ending in the same Mount Brendan where an ice cap formed during the last Ice Age. The peninsula has an ancient magic, especially outside the tourist months when fog rolls down from the hills and the walls of ancient ring forts and beehive huts loom out of the mist like ghosts from the Otherworld. There are legends that the Dingle peninsula is where the Celts, or Sons of Míl, first came ashore with their iron swords to defeat the magical Túatha Dé Danann and force them into the Otherworld, where they became the Celtic gods. Myth and history go hand in hand in Dingle. At the far end of the peninsula, a Mesolithic campsite was excavated at Ferriter's Cove and dated to around 4500 B.C., a time just before farm animals first arrived in Ireland.

One day in early fall, archaeologist Míchéal Ó Colláin traveled down to "the Kingdom," as the peninsula is called, to meet a friend. Bobby Goodwinn is a farmer in his late seventies who owns one of the Magharee islands off Tralee Bay, known as the Seven Hogs. Bobby's island has a few acres of flat treeless pastureland where he raised his family in a stone house, the only house on the island. With his wife dead and his children grown, he now lives on the mainland. The house is still there, let to summer tourists, though there is no electricity and just a hand-pumped well. At the far end of the island are the ruins of an ancient Irish monastery, its dry-stone walls slowly being washed away by winter storms. Christian monks in the seventh and eighth centuries A.D. sought out these remote places, calling their self-imposed exile the White Martyrdom. Bobby still keeps cattle on the island, letting them roam free all year until it is time to market them on the mainland.

A generation ago it was common to see farmers on outlying islands load their cattle into small boats—often traditional skin-covered currachs—to bring them to market. If distances were not too great, they would even swim them over. Cattle are good swimmers but their heads drop down when they get tired so they drown easily. Bobby has created his own unique animal transport, which Míchéal Ó Colláin calls a cowmobile. It is a wooden pen large enough to hold two cows. The platform, about 12 feet long and 5 feet wide, was built on top of empty oil barrels. Míchéal had come to help Bobby bring one of his heifers back from the island.

We set out in pouring rain from the little fishing port of Fa-hamore, towing the cowmobile with Bobby's fishing boat. A fifteen-minute journey later, he anchored the fishing boat in the bay while we poled the cowmobile onto the beach. Catching the cow was more difficult but eventually Bobby had it running across the sand, lashing out with its back legs and twisting around to stop him getting a rope over its head. "This is the modern-day version of what must have happened six thousand years ago," Míchéal explained. "Those first cattle and sheep all had to be brought across by boat. Of course the boats weren't so good, and the ropes weren't so strong."

Bobby looked up from where he was heaving the cow's hindquarters up onto the cowmobile. "All they had was stronger men," he panted. Of course the first farmers did not bring full-grown animals. Calves and lambs would have been laid on a bed of straw at the bottom of the currach with their feet tied with grass rope to stop them kicking a hole in the side of the boat during the ocean crossing. "The first evidence we have of cattle in Ireland is around 4500 B.C.," Míchéal said. "They'd have been headland hopping, island hopping, never out of sight of land. And they had to cross the sea on a calm day." Hopefully their crossings were easier than ours. As we towed the cowmobile out from the shelter of the island, the wind and sea picked up and the raft tossed and plunged like a spirited horse, with the cow bellowing mournfully the whole way over.

Ireland's first farmers probably came from Britain, crossing the Irish Sea, carrying the animals and seed crops needed to establish a farming economy. On a clear day you can see Ireland from the coast of Scotland and Wales, the shortest crossing is just eleven miles. Today it is difficult to imagine a world in which nation and nationality have no meaning. Loyalty would be to family alone, and a single extended family might have roots on both sides of a body of water. Through most of prehistory, the Irish Sea was a link, not a division, between Ireland and the neighboring island of Britain, as were the shorter sea-routes between the Irish mainland and its many offshore islands. Professor John Waddell, head of the department of archaeology at the National University of Ireland, Galway, took us out to Inis Meain—the middle and least spoiled of the Aran islands that guard the entrance to Galway Bay off Ireland's west coast—in a one-hundred-year-old Galway hooker. This fifty-foot sailing ship had bright red sails and an oak hull stained black with sea-spray and age. Such hookers once carried all the cargo up and down Ireland's west coast.

The present slips away in a sailing ship when the only sounds come from wind, waves, the creak of rigging, and the soft Gaelic language the skipper spoke with his son who held the tiller. John Waddell sat at the bow, looking out to where the island slowly drew closer. "Water was the principal means of communication around Ireland throughout ancient times," he said. "Cross-country travel was much more difficult than going by sea. Thousands of years ago the seas around Ireland would have been full of boats; fishermen, traders, even families going backwards and forwards. Communities on one side of the water often had closer family ties with people on the other side than they did with people inland."

Inis Meain is two hours sailing out into Galway Bay with a good wind, although modern ferries make the trip in less than an hour. The Aran Islands are made up of great slabs of limestone, cracked through with fissures that run northeast across the islands. There are few trees and rock is everywhere, peeping up from beneath thin soil, broken up for the dry-stone walls that ring every tiny field, or built into two-thousand-year-old stone forts like Dún Aengus and Dún Connor that dominate the Aran landscape. On the Irish mainland, where soil was good, Neolithic farmers just cleared areas of forest to plant their crops and pasture their animals. On Aran they had to make the soil itself. Hundreds of generations of islanders have carried sand and seaweed from the shoreline, spreading it out on the limestone bedrock to rot into soil before the fields could produce crops.

John Waddell had come to meet Dara Beag O'Flaherty, who still gathers seaweed from the beach to dig into his fields, as islanders have done as long as people have lived on Inis Meain. Like most on the island, Dara prefers to speak Gaelic. He cut handfuls of kelp left behind by the retreating tide and packed them into baskets hung over the saddle of his donkey. The beach was full of kelp harvesters, most with donkeys and handcarts, although one man used a big tractor and trailer. Much of this seaweed is edible and can be baked into the laver bread that was once a staple of the island diet. Rich in nitrates, it also makes excellent fertilizer. That is how Dara used it, digging it into his fields that lay in the shadow of the Dún Connor fort. "What you're seeing is timeless," John said later as he watched Dara forking the seaweed into the neatly turned rows where he would soon plant his potatoes. "Neolithic farmers on Aran probably built their fields up just the same, using the seaweed and sand to form cultivation ridges for their wheat and barley." Dara did not care that his actions had such ancient roots, but he knew the seaweed helped him grow the best potatoes on the island.

For a millennium after 4000 B.C., the weather in the Northern Hemisphere was warm and moist, temperatures several degrees higher than they are today; in other words perfect farming weather. In the Fertile Crescent, the world's first cities were developing new urban ways of life made possible by the food surpluses farming provided. In Northern Europe, Neolithic farmers were raising great stone tombs for their dead. The most spectacular of these are passage tombs, covered by mounds of earth or stone up to forty feet high and often built on hilltops to emphasize their size. Similar tombs are found in Spain, France, Britain, and Ireland, suggesting that Ireland shared its culture and a related language with much of Northern Europe at this time. More than fifteen hundred mega-lithic—the word means "made of big stones"—tombs survive in Ireland from the Neolithic Age, the majority built between 4000 and 2OOO B.C.

Building such massive tombs required strong local leadership and a ready supply of workers able to spend months away from crops and herds. Populations were much bigger than in Mesolithic times, and farming was providing food surpluses in Ireland. Four different types of megalithic tombs have been found, although why a community chose to build in one style rather than another is anyone's guess. Simplest are the portal tombs commonly known as dolmans. Thousands of years of erosion often leave nothing but the portal or gateway stones and a huge capstone, rearing up like the prow of a ship in front to slope down and rest on smaller slabs of stone at the back. The most famous of these is Poulnabrone, in County Clare.

Next come the court tombs, so called because there is an open circular or semicircular courtlike area sometimes entered through a narrow gateway that stands in front of the tomb entrance. It is impossible to tell how these courts were used; even the biggest could only hold a few dozen people. Maybe priests and tribal leaders went into the court for important religious ceremonies while the rest of the people waited outside. Or if they were simply family temples, they may have been just big enough for the family to assemble. Today visitors only see fallen slabs of stone, but court and portal tombs, like all megalithic tombs, were originally covered by cairns of rock or mounds of earth.

Wedge tombs are the most recent of all and were still being built in the Bronze Age after 2000 B.C. The burial chambers are wedge-shaped passages, which narrow and lose height from front to back, and are covered with a low mound. These barrows can be up to thirty feet long; anyone who has read J.R.R. Tolkein's epic fantasy Lord of the Rings will remember Frodo's terror at being trapped underground in such a place in the company of the dreaded barrow-wites. Legends must have grown up around the megalithic tombs within a few generations of their construction. Later people thought them the work of giants, magical entrances to the Other-world where gods and spirits lived. The most impressive of all these Irish tombs are the passage tombs, whose great hilltop mounds often tower over the surrounding countryside. Even by today's standards, they are magnificent architectural achievements. Built more than a thousand years before the first pyramids rose in Egypt, they clearly show the sophistication and skill of the Neolithic Irish.

The Boyne Valley northwest of Dublin contains sixty passage tombs built in three distinct groups. The greatest of these, the most famous passage tomb in Ireland, is Newgrange, a great mound of stone almost three hundred feet across and thirty-five feet high. Unlike court, portal, and wedge tombs, which appear on their own, passage tombs often appear in clusters in cemeteries, smaller tombs gathered around the largest mound in the center like children around a family patriarch. Newgrange is such a patriarch, built between 3300 and 2900 B.C. The tomb entrance has been open since the seventeenth century, but only a small part has been properly excavated. The Irish Heritage Service recently restored the tomb, facing the front with sparkling white quartz. Most days in summer the roads to Newgrange are choked with tourist buses, attracted to Ireland's best known Stone Age monument like bees to honey. The newly faced white tomb wall is a dazzling display as it reflects the morning sun. It seems almost modern, a gleaming mound bordered by carparks, a visitor's center, and neat gravel paths that package tourists into carefully controlled groups. Entry is restricted as the Heritage Service is increasingly worried about the damage tourism is doing to the five-thousand-year-old monument. Once inside, a passage runs seventy feet back into the heart of the mound to end in a cruciform burial chamber with a high vaulted roof. Newgrange is the only Neolithic tomb found so far with a light well above the main passage that frames the first rays of the sun on the winter solstice so they shine directly through to the back of the tomb. But for all its size and import, there is little sense of mystery in daytime. Like Stonehenge in Britain, too much bureaucratic regulation and too many visitors have leached it of its ancient power. But at dawn or dusk, with mist rising from the grass and no one around, it is still possible to understand the hold this tomb, and others like it, have had on human imagination for thousands of years.

Not all of Ireland's great passage tombs have given up their mystery to an excess of package tours and camera-clicking tourists. At Carrowkeel and Carrowmore, in County Sligo in the west, and Lough Crew, north of Dublin in County Meath, the tombs stand open to wind and weather, and sheep graze across the high hillsides where the mounds were raised five thousand years ago to look down on surrounding tribal lands. The Carrowmore cemetery is dominated by the huge mound called Knocknarea that sits on top of a high ridge of hills that overlook the Sligo coast. Locally it is called Medb's tomb or Medb's pap as it resembles a human breast. Medb was a Celtic earth goddess and the legendary queen of Con-naught who sent her armies against Cú Chulainn, hero of Ireland's most famous ancient saga, The Taín. Previous generations believed Medb herself was buried inside, but Neolithic tombs were built thousands of years before the time of Celtic legends. Knocknarea has yet to be excavated, but archaeologists believe it could contain a passage tomb at least as big as the one in Newgrange.

The Lough Crew tombs are just outside Oldcastle, in County Meath. We arrived with archaeologist Barry Raftery an hour before dawn, racing the light in the hope of reaching one of the hilltops before sunrise. Of course we got hopelessly lost in the maze of small lanes that wander haphazardly around the base of the hills on which the tombs were built. At last we stopped at a cottage with a light showing in the kitchen window. The old farmer who answered the door showed little surprise; people get up early in these parts. He simply shrugged on his coat and boots and told us to park our car in his yard. "I'll take you up myself," he said. "You'll never find your way in the dark." His name was Mick Tobin, and he told us proudly he was eighty-two on his last birthday and had been climbing the Lough Crew hills all his life. Looking like a figure out of Irish legend with his battered hat, flapping raincoat, crooked walking stick, and bowed legs, he led us on a merry chase as we panted along behind him, climbing almost a mile up a hillside slippery with morning dew to emerge where great Neolithic mounds lay in black silhouette against the lightening sky.

The wind had picked up, moaning around the collapsed stones of some of the smaller tombs. About thirty tombs remain, spread out over three hilltops, although there had been double that number. The site is known locally as Sliabh na Caillighe, or the Hill of the Witches, and Mick told us the local legend. "She was a hag and a fairy queen," he said. "She came flying by with her apron full of stones, dropping them on the three hills to make these cairns. She was about to go to another hill and leaped off—it's called the hag's hop—when she fell and broke her neck. Now she's said to be buried in a heap of stones at the back of Patrickstown hill."

Most of the older locals still swear the hills are haunted, and there is no shortage of stories about mysterious fires seen flickering around the tombs on solstice nights. Mick Tobin swears he saw a banshee there one night in 1939, but she was not crying; only when a banshee cries is someone about to die. Every new generation builds on existing folklore. Mick showed us a flat rock in the side of the largest mound. "This was the witch's chair," he said, rapping it firmly with his stick. "She was the mistress of all Ireland, and she'd sit here, smoking her pipe, and make laws for all the people. Everyone had to do exactly what she said. If they didn't, she'd cast a spell on them and turn them into anything she liked."

The sun rose as Mick finished his story, flooding the hilltop with light. The big tomb beside us was positioned to catch the sun, although without the precision of Newgrange. Yet at sunrise on a cold February morning, with sunlight flooding into the entrance of the tomb and a cold wind moaning around the fallen stones, it is easy to see why pre-Christian people believed they were magic entryways to the Otherworld. Barry Raftery remarked that Mick's folklore held echoes of ancient reality. The tombs were much more than simple burial mounds. Probably sacred to the earth goddess, they were also places of assembly where tribal laws were given and disputes judged.

"The importance of the site is the hilltop location," Barry said. "These were ceremonial places, central places within the tribal landscape, symbolizing the importance and continuity of the tribe. If you look around, you see a wide expanse of countryside. That means the dead up here could look down and watch over the living. More important, the living could look up to the dead. I imagine at different times of the year the people assembled here to celebrate the importance and unity of the tribe."

The biggest tomb on the hilltop is sealed by a heavy iron gate fastened with an ancient padlock. Barry had the key, usually kept by a farmer down the hill, and we went inside, stooping to enter the narrow passage. It is nowhere near as big as Newgrange but has much more atmosphere. The passage leads back twenty feet to open into the main burial chamber that has a vaulted ceiling twelve feet high in the center. Three chambers open off the end in the shape of a crucifix, each with a stone basin that once held cremated human remains. In each of these chambers, and along the passage itself, are slabs of stone worked with exquisite circles and whirls, as fresh today as when they were carved five thousand years ago. Most passage tombs have been found to contain just a small amount of burned bone. Perhaps like Egypt's pyramids, they were built for chosen leaders or priests of great spiritual importance, ancestral gods with power to protect the tribe and its land for all time. It is an interesting coincidence that the intricately carved spirals and circles of the artwork look like the artwork now called "Celtic," even though it would be another thousand years before Celtic people migrated west into Europe.

It was quiet inside the tomb, the light slanting in through the narrow entrance and barely reaching the burial chamber at the back. Sitting on a carved rock at the very center of the mound, it was possible to imagine what the people were like who had built such a place. They would not be so different from us, probably worried about the weather and crops, looking forward to the next celebration, concerned that their kids were running wild. We know they were small farmers, living in scattered communities that held no more than two or three houses. Neolithic Ireland was not particularly warlike, so there were no defensive walls. The houses were wood with thatched roofs, not built for permanence but presumably comfortable and dry. Such houses would disintegrate and vanish within fifty years if they did not burn down first; fire must have been a constant hazard. As Barry observed, "The houses of the living didn't need to be permanent, only the houses of the dead."

Tomb building calls for sophisticated organization and a degree of specialization in human activity. People had to be gathered together under strong leadership over a wide area. There would be architects to design the tombs so that they did not collapse under the weight of the covering mound, and stone carvers to split and shape the great stone boulders. Astronomers had to calculate the solar calendar so tomb entrances could be precisely aligned with the rising or setting sun on solstice days. Masons were needed to build the corbelled dry-stone tomb walls that curved inward until capped by a single slab. Engineers must have devised ramps and pulleys to transport and position heavy stone slabs. Artists were probably called in from far away to carve the intricate spirals, circles, triangles, lozenges, and zigzags that decorate the tombs, some positioned so only the gods could see them. There would be musicians to keep up the spirits of the workers, cooks to feed them, healers to dress the cuts, bruises, and broken bones that occur on any construction site. No doubt the priests fussed busily around, supervising everything to be sure the work was completed according to the will of the gods. It is not surprising that later people thought the mound builders were gods. It would be thousands of years before the Irish could build such spectacular structures again. Only with the coming of Christianity in the first millennium A.D. were the ancient gods demonized and diminished, the great tombs becoming no more than homes for witches and fairies, banshees and leprechauns, Irish for "creatures with a little body." It is easy to discount the old tales, but few local people will go near the tombs at night. "The hills are haunted," Mick Tobin said firmly. "Fairy folk, ghosts, banshees; believe what you want. They're here just the same."

It was mid-morning before we were ready to leave Lough Crew, the winter sun blinding after the dark stillness of the tomb. The iron gate sealing the entrance squealed in rusty protest as Barry closed and locked it behind us. It was installed to stop vandals damaging the tomb, but earlier peoples would have thought it had a different purpose. Many English and Irish fairytales tell how fairy folk cannot pass cold iron; so perhaps the iron bars serve to keep Otherworld forces in, not people out. The same belief is behind hanging a horseshoe on the front door to stop fairies and devils coming in the house to do small acts of mischief like souring milk or giving the baby colic. Such legends may be distant echoes of the great changes in store for all the people around the Irish Sea when the arrival of metal brought the Stone Age to an end and began Ireland's first industrial revolution.