THE IRISH MONASTERIES for which wealth and prestige became bywords were to be found in the rich grasslands that lie mostly to the east of the River Shannon. The monastery system that developed in Ireland was unique in European Christian terms, yet these atypical monasteries were the wellsprings from which Irish art and learning spread throughout Europe. Many consider this to be the most magnificent period in Irish Christianity.

Clonmacnoise, arguably the greatest of the Irish monasteries, which surpassed even Armagh in scholarship and learning, was also probably the most beautiful of all. It came into its full flowering of scholarship in the eighth to ninth centuries, a period of great learning and artistic development in Ireland. Today its ruined buildings stand as testimony to the significant position this monastery once held in European scholarship. Even now it is a place of beauty, peace, and tranquility. It is sited right next to the River Shannon in the center of Ireland, in an area still pastoral and idyllic. When we visited Clonmacnoise one early spring morning, Irish medieval historian Donnchadh Ó Corráin walked with us through the ruins. Experiencing firsthand its pastoral serenity, it was easy to understand why this location was chosen as a place of community and spirituality. To the ancient Irish, a people without towns or urban centers, the connection to nature was important, and beauty in a place would have had a top priority. It could not have been difficult to persuade people to live in Clonmacnoise. It became one of the largest communities in Ireland and a center of Irish and European learning. Looking at the still impressive ruins of round towers and ancient church walls, Donnchadh remarked: "Clonmacnoise was one of the great ecclesiastical centers of the [Irish] golden age. Its abbots and governing cadre were amongst the great ecclesiastic nobility of the land. It was a great center of literature and art." Like other Irish monasteries of the time, its influence spread way beyond the confines of its own parapet. Walking around the ruins with the crisp air blowing off the River Shannon, it was hard not to feel nostalgic for the long-lost Irish monastery system which was destroyed by the reforms of the twelfth century.

In the early days of Christianity in Ireland there had been an attempt to establish dioceses with bishops in charge of whole areas. But this was an urban model based on the experience of European Christianity, and Ireland had no urban centers. So Christianity in Ireland developed along the lines of the way the population lived at the time—in small communities, which eventually developed into large monasteries. But to use the word "monastery" is a bit of a misnomer as the monasteries that developed in Ireland during these centuries bore little resemblance to what we now think of as religious communities. They were religious, but they were not ascetically monastic as we would understand the word. They were not like modern-day monasteries or even monasteries of the Middle Ages where monks observed a regular order of life.

As Christianity in Ireland spread, the monasteries became large nucleuses of population. This is a significant part of the story of later Irish monasticism. They were much more than monasteries; they became whole communities developing along the lines of the society that had founded them. It used to be said that the Irish founded monasteries because they wanted to isolate themselves from others and be closer to God, but in fact the Irish monastery system was not a place of isolation. Monasteries were large, thriving centers of activity and worldliness.

By the end of the seventh century great monastic towns had sprouted all over the country, but they did not espouse austere monkish lifestyles. They referred to themselves as "monastic cities," and they certainly were the closest thing that Ireland had to urban centers. Within the monastic towns were workshops and markets filled with the hustle and bustle of daily life. The monastery was not just one large building as it would be today but was made up of many structures including work areas, living quarters, and places for trading and bartering goods. Irish monasteries were in fact thriving communities incorporating all aspects of secular life.

By the eighth century the monasteries had been almost completely secularized while remaining Christian in ethos: they celebrated the life of Christ but were also very much integrated into the material world. They had moved away from the Roman or European idea of monasticism as isolation and developed a system and living style unique to Ireland. Whole families lived and worked within the monastery town. The abbots who ran the monasteries were usually married men and had families of their own. Celibacy was not considered a necessary component of monastic life in Ireland. The monks themselves were also usually married, and it was these families that made up a large part of the monastery town. On the death of an abbot the usual practice was for one of his sons to inherit the monastery and become the new abbot. Although there was no exact order of succession, the monastery and its wealth all stayed within the family.

Extensive writings survive from this period which allow us to know quite a lot about Irish society and the monastic system that became the most important feature of Irish life at the time. We know that the monasteries were very closely connected and integrated into the upper ranks of Irish society. The abbots belonged mostly to the royal families and were wealthy and influential men. The land that the monastery was originally built on had often been donated by a royal family, and one of the family's sons or brothers would likely have been the first abbot. It was not unusual for an abbot to hold the title king and abbot, often the abbots had brothers or fathers who were kings. This traditional connection with a particular family line sometimes continued for many centuries. For instance, the king of the Uí Néill had a house at Armagh and lived there for part of the year. The Leinster king lived sometimes at the monastery of Kildare where his brother was the abbot and his sister the abbess. The abbots themselves, being aristocrats, frequently married women from the royal houses and led lives like princes.

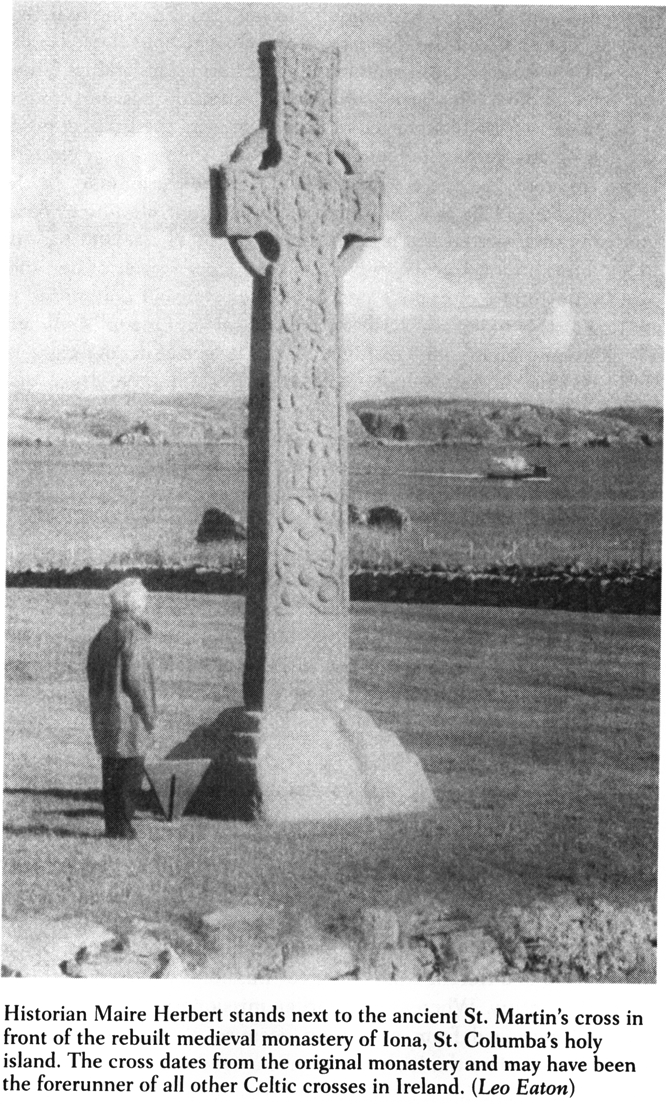

Some larger monasteries controlled or "owned" other smaller ones. Armagh and Iona were the two most powerful ecclesiastical centers of the Irish church. Iona had dependent churches both in Ireland and in Scotland and owned monasteries at Derry and at Kells, in modern day County Meath. Armagh had a whole network of dependent churches across Ireland. It claimed to have been founded by Patrick, and from the seventh century linked itself to the rising dynasty of the Uí Néill. Armagh therefore claimed primacy over the whole of Ireland. This supremacy was generally acknowledged by the end of the seventh century. Clonmacnoise likewise sat at the head of a number of smaller communities and all of these lesser monasteries would pay taxes to their head monastery.

This is not to say, however, that Ireland had a church hierarchical system like the rest of Europe. It did not. Individual churches and monasteries enjoyed a great deal of independence. Some churches were allied to the larger monasteries but many were free, that is, they were under no obligation to a higher church or monastery or even to the original owner of the land. Others were not so free and had to pay taxes to the family that had originally donated the land to them. This payment might persist for many generations. At the top end of the scale were the largest monasteries, with their royal alliances, with dependent churches and smaller monasteries paying taxes to them. At the bottom of the scale the smallest church would consist of a church and perhaps a graveyard serving a local community. The average person living on the land at this time was not bound to an overlord as he might have been in Romanized Europe. The commoners were freemen and usually owned their land and had rights under the law. So the smaller churches served these people and very often were independent of the larger ones. There might only be one priest in such a church and his son would inherit the job on his father's death.

The position of women within Irish Christian society is very interesting and one that has been given much scholarly attention recently. We know that the abbesses were an important and vital part of Christianity in Ireland during its developing process. In the early days of conversion the Christian missionaries and converts had more or less tried to live separately from those who were still espousing the pagan gods and goddesses. But these early Christian converts were not gender conscious or biased in that both men and women in Ireland worked together to bring the Christian message to others. Ireland differed also from the rest of European Christianity in that women neither became separated from the mainstream of Christian preaching nor were they forced to go into enclosed convents.

The Irish abbesses were as much a part of mainstream Irish Christianity as were their counterparts, the abbots. The abbess in Kildare for example, was for some time also a bishop. The legendary St. Brigid was said to be the original abbess there, but as the medieval historian Elva Johnston explains, "Brigid is given the status of bishop for the first time in a ninth-century life of the saint, but it probably dates from at least a century earlier. At first it was believed that this rank only applied to Brigid, but then it was claimed that her successor abbesses would also be awarded the status of bishop." It seems that the abbesses of Kildare held the title of bishop for hundreds of years. Many religious women served as wives to priests and monks and fulfilled their roles in religious life through the men they were married to. But the influence of a wife cannot be discounted easily. The wife of a priest or an abbot must have had quite an influence on the running of the monastery and the direction of Christianity in general. Although the actual power that women held in the early Irish church is debated, it does appear that they were certainly not as marginalized as they would become after the later twelfth-century reforms.

Although the sixth century saw the heroic age of the Irish church when famous founders like Colmcille did their work, it was not a time when art flourished. It was at approximately the beginning of the eighth century that the great Irish artworks come into prominence. This significant period in Irish history heralded in a time of tremendous achievements in the arts and in scholarship. Monastic worldliness contributed to the great flowering of the Irish church. The monastery towns had the wealth to maintain vast workshops to attract craft workers of the highest skills.

The wealth of the monasteries lay in many sources. They owned extensive rich farmland which formed the basis of their wealth. They also encouraged pilgrimage, and the pilgrims paid very well for the privilege of staying in the monastery. Pilgrimage in those days was as popular and profitable as tourism is today. In fact pilgrimage became a significant part of the income of many monasteries. Although some monks had it prescribed for them as atonement for sin, most of the lay people who went on pilgrimage did so for fun. Saints' feast days, especially the founding saints of monasteries, became days of celebration and pilgrimage. From early on we know, for example, that March 17, the supposed date of Patrick's death, was a day of celebration at Armagh. Another source of income lay in relics. The larger monasteries had valuable relics which were carried around in times of plague or sickness, and people would pay quite an amount to have a relic brought to a sick friend or relative in distress. The lesser monasteries paid taxes or rent to the larger monasteries they were governed by. The wealth of the large monasteries formed the backbone of the Irish economy of the time.

In these rich monasteries the demand arose for exquisite liturgical vessels and for beautiful gospel books to grace the altars of these wealthy establishments. The rich abbots living in the prosperous monasteries had the resources to pay for the creation and development of the beautiful manuscripts and chalices associated with this time. The monasteries seemed to have a taste for opulence in design, which was perhaps a part of their worldliness. Whatever the reasons, this is the period of great Irish art in manuscripts, metal, and stone. The large wealthy monasteries ran scriptoria and workshops in stone carving and metalwork where aestheticism in design was held in very high regard.

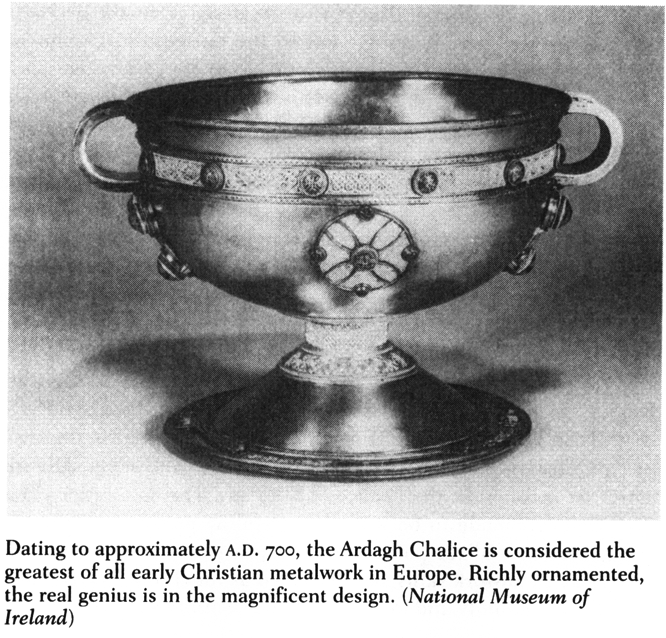

One of the greatest examples of exquisite Irish artwork from this era is the Ardagh Chalice. On display in the National Museum of Ireland in Dublin, this chalice is considered the finest example of Irish metalwork of the eighth century. It was given its name because it was discovered in a bog in 1868 in Ardagh in County Limerick. It actually dates to approximately the year 700 and is regarded as the epitome of Irish craftsmanship of the period. This extraordinarily beautiful chalice is made of silver and bronze and ornamented with gold filigree. But it is in its design that the aestheticism and genius lies. When we visited the museum in Dublin we were privileged to see the chalice outside of the protective glass case where it is usually displayed. It is a marvelous achievement in metal work. Pat Wallace, director of the museum, described it for us as "The best quality in Europe of its day: gold, wirework, so-called filigree in the girder around the top. The bowl and the base are separate, silver, cast bronze dipped in a kind of a gold in the middle of the stem, and then gold foil work. Then there are the studs around it, underneath the handle, in the handle, and studs around the girder. All of those have blue and red enamel. That's a technique that originated in the Roman world and was perfected and developed here by the Irish."

Another achievement in Irish art of this period is the Tara Brooch, so named because it was discovered on a beach close to the hill of Tara. The interesting thing about this item is that it is not a Christian object but has been made with the same skill and care that is found in the chalices of the day. This is a brooch that was obviously made to be worn by a wealthy person as a prestige object. As Pat Wallace pointed out, "It just shows us that great art and great metalwork skills were lavished as much on everyday artifacts for the nobility and for a king as they would be for early Christian objects." This is an interesting observation and is an indication that Irish Christianity of this time seems to have made no distinction between the spiritual and material world. Both were accorded the best work of the superior craftsman.

Part of the daily routine of monastery life was the transcribing of the gospels and other manuscripts, including grammars. In an age before the printing press it was the only way to get a copy of a book. Many of these copies were for personal day-to-day use and written without much decoration. Transcribing was such a commonplace practice that often the monks wrote poems and notes in the margins of the pages they were copying giving us interesting insights into their daily lives. While the gospels or psalms were usually written in Latin, these margin notes, and poems, were written in Irish. Many interesting pieces of information can be gleaned from these annotations, from complaints about the cold conditions they were writing in, to love poems. One poem, written by a scribe about his cat, Pangur Ban, or White Cat, is an amusing and charming piece of ancient doggerel. The opening lines are:

I and Pangur Bán, my cat

Tis a like task we are at;

Hunting mice is his delight

Hunting words I sit all night.

But some gospel books were important works of art. Manuscript illumination in Ireland saw its major development in the eighth century. Irish contact with scriptoria in Britain and continental Europe brought about an interplay of diverse influences to this art form. Still, the general tendency in Irish illumination was towards a greater increase in ornamentation and design developing into a uniquely Irish form of abstract artistic expression. Scriptoria were to be found in all the large Irish monasteries, and many of these manuscripts have also survived. They represent fine examples of how highly skilled the Irish monastic scribes had become.

The Book of Kells is the greatest of these manuscripts; it has no rival for decoration, skill, and beauty. It is a brilliantly illuminated copy of the four gospels written in Latin in a text form known as Irish majuscule. Although there is no direct evidence regarding its precise provenance, it is thought to have been designed and written by Irish monks on the island of Iona some time in the late eighth century. It may have been created to mark the two-hundredth anniversary of the death of Colmcille, the founding saint of Iona. It is believed that it was subsequently carried to the monastery at Kells in Ireland, possibly as a result of the Viking attacks in the later centuries. The book was unfinished at the time it was brought to Kells, and work was done to complete it there, although it was never absolutely finished.

This magnificent manuscript is said to be the work of an entire scriptorium working together in its production: scribes and painters collaborated in its inception. Nevertheless, creative license is apparent on every page of the manuscript. There was considerable artistic freedom permitted in the creation of this work which differs from continental manuscript illumination of the time. It is extremely ornate and much more elaborate in design than its European counterparts. Francoise Henry, an authority on the Book of Kells and its origins, says of the Irish scriptorium which produced the book, "Like the scribes, the painters belonged to a scriptorium where there was no watertight compartments and there was sufficient give and take to produce a common flavor in the work, whatever the individual tendencies of the artists." The basic design is complex yet delicate in its intricate ornament and mastery of artistic patterns. Capital letters are filled with circles, spirals, animals, birds, and small human figures which sometimes protrude menacingly above the text. The symbolism of it all remains unknown, but it is without doubt the greatest illuminated book found anywhere in Europe of this period. Today the Book of Kells is housed in Trinity College, Dublin, where it is displayed to tourists in its own interpretive center at the university. The book is in a protective glass case, and a new page is turned each day.

The most distinctive, visual feature of Irish monasteries of the ninth century were the enormous High Crosses, sometimes referred to as Celtic crosses. These impressive, large, freestanding stone crosses are still to be found scattered across Ireland on the sites of many of the ruined monasteries. Some stand as high as twenty feet. They are the product of the fine stone workmanship common in Ireland at a time when stone carving was rare in the rest of Europe. The crosses are elaborately carved with images from the Bible. The stonework designs are comparable to the contemporary Irish metalwork and illuminated manuscripts and display similar abstract designs and ornamentation.

The unusual design of the cross is the most notable feature: a ringed cross head is mounted on a solid stepped base. The ring is the most distinctive and familiar feature of the cross, yet its origin is uncertain. Some scholars believe that the ring on the High Crosses has a practical origin and may have been developed for structural purposes. The large stone cross head, they suggest, would be unsound without the help of the ring to support it. But this theory fails to take into account the possible symbolism of the ring design. Earlier ringed crosses were found on slabs, and the ring design may have connections to the older pagan icon the sun. There is a ringed cross design on a linen wall-hanging from Egypt dating to around A.D. 500 which foreshadows the design on Irish crosses. The ring may also be a symbol of triumph as it was in ancient Rome, and it may be a representation of Christ's triumph over sin. Perhaps the true origin of the cross motif is best understood as a necessary structural design which also had some symbolic meaning, possibly inspired by earlier circular icons.

When we view these enormous stone monuments today we see them in gray stone, but this is not how they once were. It is now believed that originally they were painted with bright colors to enhance their appearance: a representation in stone of what was being painted in the illuminated gospels. Over the years the paint on the crosses was eroded from exposure to the elements. In their original colorful glory they must have been an extraordinary sight for a visitor to encounter when they came on a monastery and saw such a marker for the first time.

Remnants of more than two hundred stone crosses are to be found in Ireland today, representing only about half the number believed to have once existed. The crosses seem to have served a number of purposes. They might have acted as boundary markers to the monastery for pilgrims and others who came to visit. It has also been suggested that they could have been status symbols, and the elaborate designs and impressive size of some of them suggest this. Yet one of the main functions was to act as a sort of bible of the poor in that they depict scenes from the Old and New Testament and therefore "told" these stories to those who could not read. For this reason they are sometimes described as "sermons in stone." But they do not depict the stories of the Bible in any systematic way. Images were carved for their spiritual or symbolic meaning to emphasize some fundamental aspect of Christianity. They sometimes also contained specific references to the monastery where they stood. The great cross at Clonmacnoise, known as the Cross of the Scriptures, has a representation of the founding of the monastery. Carved on one side is the Uí Néill king who granted the land, and on the other side is St. Ciaran, the founder of the monastery.

A major attribute of Irish monasticism from the eighth century on was that of scholarship. Irish monasteries became large centers of European learning. Many foreign princes and scholars traveled to Ireland to attend Irish schools for their education. At the height of its influence Clonmacnoise had about 2,500 students within its parapet, many of whom had come to Ireland from Europe to be educated. They studied the Psalms and the Gospels, but they also developed a culture of Latin grammar and of Latin scholarship. Greek was also studied. This love of linguistic erudition passed into the vernacular, the Irish language, and the Irish were the first people in Europe of any vernacular language to write their own grammars. From the year 700 there were excellent written grammars in the Irish language. This is when much of the ancient literature of Ireland was first written down from the oral sources. Ireland has the oldest literature in Europe in a native language. Stories of heroines and heroes and Celtic gods and goddesses were all committed to writing at this time. The scribes probably saw in Queen Medb and Cú Chulainn champions of their own past whose deeds might be described as the equivalent of the Old Testament of their own people.

But the work did not consist only of copying down older stories. At this time a lively literature in the Irish vernacular flourished, and much of that written literature was new. The Irish took the traditional metrical Latin verse and made it their own. A new syllabic form of Irish lyric poetry was created. Poets still held one of the most honored positions in Irish society, and the poets of this period left behind a legacy of poetic originality and greatness.

Likewise, as they were writing books on Christian canon law the scribes also wrote down the ancient Irish laws—the Brehon Laws, which continue to be a source of keen scholarly interest; they supply us with a fascinating insight into early Ireland.

The Irish were eager and enthusiastic about education, and out of this passion came the desire to spread their learning abroad. While in the past they had gone overseas as Christian missionaries, now they went to Europe as learned scholars to spread knowledge. The character of the movement of Irish scholars into Europe during this period is different from the great missionary movement of the seventh century. Whereas the earlier missionaries had eventually been discouraged from preaching because of their independent spirit, by this time the Irish had gained a solid reputation for scholarship. The superior learning of the Irish schools had become an established and widely acknowledged fact. These scholars traveled from Ireland bringing learning and knowledge with them at a time when European scholarship had all but vanished. During this period, known in Europe as the Dark Ages, the continent was thronged with the Irish who were now going abroad in droves to take up positions as advisers, scholars, and astrologers in the royal courts.

For hundreds of years Irish scholars were to be found at the European courts, particularly in the Carolingian and Frankish empires. Irish scholars like Dicuil, who wrote tracts on geography, grammar, and astronomy, and the poet Sedulius, who was the leading scholar-courtier at Liége, became a common feature of court life. Dicuil's great work, Liber de Mensura Orbis Terrae (Concerning the Measurement of the World), contains an important summary on geography and gives concise information about various lands. He drew on many earlier sources but added the results of his own investigations. Dicuil is the first source for information on Iceland because of reports he obtained from Irish monks who traveled there sometime before A.D. 795. He recorded their descriptions of the landscape and the midnight sun some fifty years before the Vikings arrived there and settled the country. The Irish poet Sedulius has left behind some ninety poems and a significant treatise on an introduction to the logic of Aristotle. Irish scholarship was held in such high esteem during this era that no European court considered itself to be well served without the presence of at least one of these Irish scholars.

One of the most outstanding of all these learned scholars was Johannes Scottus Eriugena, or John the Irishman. The word "Scottus" means the Irishman, and 'Eriugena" means born in Ireland. During the ninth century, Scottus was one of a number of Irish scholars working in the area of Reims in France. The philosophical writings of Scottus were so far beyond his time that his work was not appreciated until the time of the early Renaissance philosophers. His true contribution to Western philosophy and the recovery of his writings in recent times has been a major source of interest. Bertrand Russell called him "the most astonishing figure of the early Medieval period." Scottus's mind grew and flourished in the Ireland that he was born into and grew up in. The freedom to think and go beyond the accepted teaching of the time was part of the Irish scholastic ethos of this period. With monastic worldliness came curiosity, and with that came innovative thinking. This is one reason why Scottus is so remarkable—he was able to swim intellectually beyond the accepted Christian norms of his own era.

Johannes Scottus Eriugena was born around the year 800 and was resident at the French court in the middle of the ninth century. He was appointed by King Charles II of France (known as Charles the Bald) to his court at Compiegne near Laon as supervisor of the court schools. His mind belonged to a later age, and he was condemned by various church councils for espousing such radical thinking as free will and questioning established Christian thinking on the origin of the universe. Scottus taught that man should not be completely dependent on any authority for spiritual direction but that free will plays a role in salvation. He was pantheistic in his theological tendencies and believed in accessing God through direct revelatory experience. In this way he foreshadowed later Christian mystics. He also maintained in his writings that reason does not need the sanction of authority but that reason itself is the basis of authority.

His Greek was unusually fine for the period he lived in. In Ireland at this time, Greek was studied and learned whereas in the rest of Europe it was virtually unknown. Consequently Scottus translated into Latin the work of Pseudo-Dionysius and added his own commentary. He was the only scholar of that period to produce a complete philosophical synthesis, De Divisione Naturae, the first great work of its kind in Western Europe. He came into conflict with Pope Nicholas I for his radical thinking and Neo-Platonism but was supported by Charles and remained at his court. His original thinking would not endear him to the establishment of his day or for many days to come. He died in approximately 875, but as late as 1585 Scottus's work was condemned by Pope Gregory XIII as heretical. In 1681 his De Divisione Naturae was placed on the "Index of Forbidden Books" by the Vatican. By the twentieth century, however, he was being recognized for the genius that he was.

Understanding Johannus Scottus and his ability and willingness to think beyond the confines of orthodox dogma is perhaps a way of understanding the Ireland of his time. The plethora of philosophers and scholars produced in Ireland in this period is a testament to the level of learning cultivated by the Irish schools. That Ireland could produce thinkers like Scottus shows the broadness of mind and intellectual range typical of the Irish centers of learning. Like the scriptoria and the other art forms that flourished at the time in Ireland, scholarship was not confined to convention. As Europe stagnated, the Irish schools grew to maturity with the power of freethinking. The Irish scholars are evidence of a sense of erudite confidence and belief in intellectual exploration which seems to have been nurtured in the country during that period.

Life within this monastic system was not always peaceful. As the large monasteries became increasingly wealthy they found that more and more they were the targets of both the kings and other monasteries. Very often the rich monasteries were attacked and plundered for their wealth. In later centuries the Vikings were to do this on a grand scale, but years before the Vikings came to Ireland there were monastic raids and battles between the monasteries. One of the earliest records of a monastic battle is written in the Annals of Inisfallen in 664, about fighting at the monastery at Birr. In 760 Birr went to war with Clonmacnoise to settle some differences. Four years after this there is a record of a large battle between the monastery of Clonmacnoise and that of Durrow in which the records tell of two hundred of the monastery community of Durrow being killed. In other words, these monasteries were behaving very much like city-states and fought over issues between them. Donnchadh Ó Corráin describes these battles: "We do know that there were monastic troops, of course, and even before the Viking period we find pitched battles between monasteries. That is to say monasteries had contentions and quarrels, presumably over property and income. There's a pitched battle between [the monasteries at] Cork and Clonfert, in which there was an innumerable slaughter, the annals say, of the ecclesiastical heads and superiors of Cork."

These battles were not just fought between monasteries. Monasteries were also often the targets in political disputes. In 780, for instance, the Annals of Ulster relate that in a war between Leinster and the Uí Néill, the over-king of the Uí Néill "pursued them [the Leinstermen] with his adherents, and laid waste and burned their territory and churches." In 793 Armagh, the chief ecclesiastic center of Ireland, was attacked and plundered by an Irish king. From all of these accounts it is obvious that the monasteries had armies with which they would defend themselves, or they would attack other monasteries or kingships if the need should arise.

The monasteries had become so rich and powerful that in times of crisis in society, especially in times of crop failure or any shortage of food, secular violence against the monasteries escalated. A cattle plague in 777 was followed by raids on the monasteries of Kildare, Clonmore, and Kildalkey. This type of attack in times of need continues for hundreds of years, and in 1015 the Annals of Inisfallen report that most of the churches of Munster were vacated because of the scarcity of food. In the same year they tell of much looting of the monasteries in the area.

What is very clear from all of this is that the monasteries had become well-known as populous centers of wealth. The attacks on them had nothing to do with anti-religious feelings. It was simply that the monasteries had the resources and the means of survival. Consequently, in times of societal stress or need they were the obvious targets of attack and plunder. For this reason the Irish kings attempted to dominate the monasteries or place their close relatives in the position of abbot or abbess. As the violent assaults on monasteries predated the Viking plundering, it is incorrect to say that the Irish were following Viking example, as has sometimes been claimed. Native attacks had more to do with the perceived economic growth of the monastery towns; they were not the result of imitating Viking patterns.

In spite of the wealth and prestige of the monasteries, the kings and their families remained a vibrant force in Irish society. It is difficult to say exactly how many petty kingships there were in Ireland at the time, but it is estimated that there may have been around a hundred. But the position of an Irish king was not like that in the rest of Europe. A king in Ireland had no real power. An Irish king did not "own" the land as he did in Europe, and, unlike European kings, he did not have the authority of a judge or a lawmaker. He was simply the representative of his people or a leader of his people in times of war. The high-kingship was a title without any real meaning. The Uí Néill had claimed the title high-kings of Ireland for centuries, but it did not mean much beyond the prestige of such a title. Irish high-kings were first among equals, rather than rulers of the entire country. Significantly, Irish kings were not above the law. Their authority came from a mixture of their own personality and charisma, military strength, and an ever-changing network of alliances with lesser kings or chieftains. Another important difference between Ireland and the rest of Romanized Europe was the absence of order of succession based on birthright. In Ireland primogeniture, the heir being the oldest surviving son, was not the practice. Instead, on the death of a king or a chieftain, senior members of the court would meet in what was called a dáil, or discussion group, to decide the next leader.

The precise details of the inauguration of a king are not clear, but we do have some idea of who would have participated and how the ceremony might have been conducted. The chief poet was an important presence at the event. He (or she, perhaps) was usually there to recite in verse the genealogy of the new king and give some credence to his fitness to be respected in his role. A ruler's genealogy, real or invented, was important because it established the sense of his "Irishness" and his family line going back to prehistory. The poet would have also been there to recite poems giving advice to the new king on how to rule and how to be a just overseer of his people's affairs. There is evidence to suggest that it was the chief poet who was the actual officiant of the ceremony and not the ecclesiastics who were also present. The calling aloud of the name and title of the new ruler was an essential part of the ceremony. This proclamation of the actual name of the king was vitally important, and the chief poet, who was the master of the word, as it were, was therefore the true kingmaker. The Lia Fail, or stone of destiny, is said to have cried out at the inauguration of a true king. This apparently happened with some frequency. It is easy to assume that some kind of precaution must have been made to assure that the stone would cry out at the appropriate time.

In Ireland, as in many places in Europe, the king was seen as a sacred person. People believed that with a rightful king the crops would grow, the cattle would be disease free, and the rivers and lakes would be full of fish. To cement this sacredness, part of the Irish inauguration ceremony involved a "sacred marriage" of a king and a goddess, very often the goddess of the territory. The feast of Tara, in which the king of the Uí Néill was solemnly wedded to the goddess of Tara, was a ceremony that went on for hundreds of years into the Christian period. Some time in the early part of the ninth century the "ordination" of high-kings began, perhaps as a carryover from the pagan practice of godly marriage. One of the Uí Néill kings, Áed Ingor, was probably the first king of Tara to be ordained at his inauguration. This practice of Christian ordination was to spread to Europe as Irish scholars brought the idea abroad.

Later descriptions of the inauguration of Irish kings, from the twelfth century on, describe in more detail the actual rites of the ceremony, but these descriptions lack validity. They are based chiefly on the work of Giraldus Cambrensis, the Norman chronicler who wrote a history of Ireland in the twelfth century and who shows a marked prejudice against the Irish. He was, after all, writing in part to justify the Norman invasion. His descriptions of incest and bestiality are most likely barbarous propaganda against the pagan practices of the Irish. By the twelfth century the Irish were being portrayed in Europe as being in need of religious and moral reform.

Socially by the eighth century the lesser kings were on their way down in society, and their importance had greatly diminished. Some of them would not be referred to as king but as taoiseach or chieftain. It was the five or six kings of the provinces who were the real players in Irish society. Many of them had managed to extend their territories beyond their traditional lands by winning allegiances with smaller kingdoms. The annals are full of the battles and deeds of these few provincial kings. In many ways they had become the celebrities of their day. In the north the powerful Uí Néill had extended their territory to include all of modern-day Donegal and had also expanded east and south through Leitrim and Longford into the midlands. For centuries they had claimed the kingship of Tara, which always remained the most prestigious kingship. In a sense central power was developing slowly, and it was inevitable that a king would emerge who would try to make himself true king of all Ireland. Such a man emerged in Munster and he was the first to try to become a meaningful high-king. To do so he would have to challenge the power of the Uí Néill. That he failed is not surprising, but the methods he employed were sometimes so outrageous and seemingly excessive that they ensured that his name would not be forgotten.

As religion and politics were closely linked together, the royal houses often played major roles in the running of both church and state. Some royal families combined the power and the aspirations of both kings and bishops. One man who held both a civil and ecclesiastic title was Feidlimid Mac Crimthainn. He was certainly one of the most colorful and interesting characters to emerge from early Irish history. He was at the same time both king of Munster and bishop of Cashel. Feidlimid was king of Munster from 820 until 847 and Cashel, his bishopric, was the primary seat of Christianity in Munster. It was also the ancestral royal seat of the kings of Munster, and King Feidlimid was one of the Eóganacht family who had ruled Munster for generations.

By the eighth century the Eóganacht were second only to the Uí Néill of Ulster in prominence and were almost as clever at inventing ancestors. The Eóganacht claimed that angels pointed out the site of Cashel to their founding ancestor and that their king had been baptized and blessed by St. Patrick. It was fairly predictable, given the climate of prestige and competition which prevailed among monasteries and kings alike, that sooner or later one of the Eóganacht would challenge the Uí Néill to the position of high-king. In spite of the fact that the high-kingship was not a powerful political position, the title carried a great deal of prestige. Feidlimid wanted the prestige for himself and his own dynasty, the Eó-ganacht, but he also had ideas of kingship which were beyond his time in Ireland. He was ruthless and unrelenting in his pursuit of his objective. Ironically he was one of the Céll Dé, an ascetic group within Irish Christianity which espoused strict observance. Considering how he went about achieving his goals it is difficult to understand this, but perhaps he was driven by conviction. Whatever his private beliefs he made no allowance for anyone who got in the way of his ambitions.

Even today the rock of Cashel is an impressive sight. Situated close to the town of Cashel, its steep incline can be seen for miles around. It was originally used as a fortification for the Eóganacht dynasty as early as the fourth century. Cashel was taken over by Christian influence early on in Irish Christianity, and it had always considered itself to be second only to Armagh in Irish ecclesiastic affairs. It had at one time aspirations of being the main center for Irish Christianity. A number of Munster kings also held the title bishop of Cashel, and it was here that the kings of Munster were traditionally inaugurated. The site was formally given to the church in 1101, thus ending any pagan or political associations with it. Today, a ruined thirteenth-century cathedral stands on the top of the rocky hill where once kingly inaugurations and Christian ceremonies took place. The climb up the rock is quite steep, and legend has it that it was abandoned as a religious center when an archbishop could no longer make the climb to his cathedral. But during the time of Feidlimid Mac Crimthainn it was a thriving community and the proud capital and ecclesiastic center of Munster.

King-Bishop Feidlimid led quite an active life by all accounts. The annals include numerous references to his antics which make for startling reading in our time. He plundered monasteries for their wealth and carried off untold bounty. He is credited with plundering the monasteries at Kildare, Durrow, Fore, and Gallen. He fully understood the economic and political power of the monastic communities, and in his attempt to gain the high-kingship of Ireland made various attempts to get the larger monasteries on his side. He put in a candidate for abbot in Clonmacnoise and went to war with the monastery when it appeared his man would fail. He attacked the monastery a number of times and plundered it. Feidlimid's candidate ended up being thrown into the River Shannon by the monks of Clonmacnoise. Being a candidate for abbot in those days obviously sometimes had its downside.

Feidlimid was not daunted by these events. He then interfered directly with the politics of Armagh. The support of Armagh was of primary importance to him and his ambition. He was astutely aware of the political significant of this center in both secular and ecclesiastic affairs. A strong high-kingship of all Ireland was favored by Armagh as a necessary corollary to its own claim of ecclesiastic primacy. But Armagh was riddled with disputes over succession and experienced many bitter struggles over the question of rights to the abbacy. At the time of Feidlimid two rival candidates were fighting over the abbacy there. When the Abbot Diarmait was expelled from Armagh and Forannan was installed in his place Feidlimid attacked the new abbot and imprisoned him in the hope of having him set aside and replaced by his own supporter, Diarmait.

Feidlimid's ultimate aim was dominance over the powerful Uí Néill, and on numerous occasions he raided the lands of the Uí Néill in Ulster. He led serious attacks against the Uí Néill in 823 and again in 826 by invading their territory, but he did not make the gains he wanted. Finally in 827 he managed to persuade the king of the Uí Néill to meet him at Birr for a peace conference. Its outcome is unclear. The Munster annals record that it was at this time that the Uí Néill recognized Feidlimid's supremacy, but as no other annals record this, it is difficult to conclude that this in fact happened. The Munster annalists were probably reflecting their own bias in what they would have wished to happen or, it has been suggested, they might even have been told by Feidlimid what to write. It is doubtful that the Uí Néill, under relatively little pressure, would grant such an honor to a Munster king. Some time after this in 838 Feidlimid met with the king of Tara, Niall. The meeting turned very nasty, and Feidlimid is described in the annals as seizing Niall's wife, Gormlaith, and her female retinue. This was obviously an insult to the entire Uí Néill dynasty. Gormlaith was an important woman in her own right and was later described in her obituary in 861 as "Regina Scotorum," the Queen of the Irish.

But these outrageous and flamboyant gestures would not gain Feidlimid the high-kingship, which at the time depended also on the favor and respect of the lesser kings. Shows of power alone were not enough to convince the Irish that someone should be high-king, and Feidlimid did not gain the allegiances he would have needed. Niall is reported in the Ulster annals as defeating Feidlimid in a battle in 841 and again stopping his progress into Ulster, but this still did not put an end to Feidlimid's ambition. Two years later, in 843, he burned and attacked the monastery town of Clonmacnoise and according to their annalists it was done "without respect of place, saint or shrine." In the Annals of Clonmacnoise, St. Ciaran, their long-dead founding saint, is described as being so angry that he is said to have appeared to Feidlimid after he returned home to Cashel and to have given him a poke with his staff which eventually caused Feidlimid to die of the flux.

Yet is has to be acknowledged that Feidlimid was the most powerful king (and bishop) of his time. The fact that he ultimately failed to gain the high-kingship of Ireland was not entirely indicative of his personal failure but rather that the times were not quite ripe for such a king. The Uí Néill remained a dominant power in Ireland and it was shortly after this time that they produced one of their most powerful leaders, Máel Sechnaill. It would take a stronger personality and another set of circumstances to topple the Uí Néill from their superior position.

Remarking on Feidlimid's career Donnchadh Ó Corráin says, "He engaged in very clever politics . . . and it's quite plain that Feidlimid Mac Crimthainn saw himself as the most important king in Ireland. But the tradition that the Uí Néill were the premier dynasty, the paramount dynasty, and the title king of Tara had such a high honor and such a long history that the kings of Munster really don't make it for being dominant in Ireland until the tenth century." Nevertheless it is obvious from the career of Feidlimid that the idea of a powerful overlordship of Ireland was beginning to take hold in the minds of some of the more influential families. He died in 847 without achieving his ambition of the undisputed high-kingship, but his exploits serve to show us that Ireland was changing politically. Provincial kings were no longer willing to accept the status quo, and kingship in Ireland was beginning to develop along a more European-style model. The idea of a central kingship was taking root.

Ireland was about to undergo great social change as well. The Vikings from the northern European region had begun to plunder and attack the wealthy Irish monasteries. They came in their long-ships along the Irish coast but soon had penetrated the land by their voyages up the rivers. They would eventually settle and form the basis of the first Irish towns, and their legacy would play a significant and enduring role in Irish history and politics.