THE VIKINGS seemed to appear out of nowhere, slaughtering their way into history in A.D. 793 when they attacked the monastery at Lindisfarne on the northeast coast of Britain. They had first raided Britain several years earlier, but it was the destruction of a church at the religious heart of the kingdom of Northumbria that caught people's attention. Two years later these Norsemen (men from the North) swept down the west coast of Scotland to terrorize the lands around the Irish Sea. It was part of a much larger Viking movement out of homelands in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden that would—over the next two centuries—overrun much of Scotland, England, and France, create the first kingdoms of Bussia, settle Iceland and Greenland, and reach as far as North America. But in 795 this was all in the future. The first Vikings to attack Ireland were just hit-and-run raiders who came from Norway, perhaps by way of the Scottish Isles. They attacked Colmcille's monastery island of Iona off Scotland's west coast before crossing the Irish Sea to come ashore on Bathlin Island, off County Antrim in the north. Then they continued around the northwest tip of Donegal and sailed south to the island of Inishmurray, four miles off the Sligo coast. Those first attacks had a shattering effect on Irish coastal communities.

The monastery island of Inishmurray is shaped like a leaf, less than a mile in length and half a mile at its widest point. It has been deserted since 1948, when the last forty-six islanders left for the mainland. Ruined houses still line the island's only road, an overgrown path that hugs the shoreline facing the mainland. Today gulls are the island's principal inhabitants—quarrelsome around people, especially during early summer breeding season when they do not hesitate to attack. They screech in so close their beaks can draw blood as they drive visitors back to the shore. Only then do the gulls circle back to land on the encircling cashel wall of the monastery, screaming defiance at all who dare invade their territory. Monks who lived here twelve hundred years ago were not so lucky.

Historian Charlie Doherty arrived on Inishmurray to visit one of those places where the Viking story in Ireland really started, little changed from how the island looked in A.D. 795. There is no harbor, so visitors must jump ashore from a small fishing boat onto sea-slimed rocks, just as early monks did, crossing in skin-covered cur-rachs from the mainland only when the sea was calm enough for landing. Even today visitors cannot land in bad weather while only the foolhardy come in winter when sea swells against the rocks can rise and fall as much as six feet. There was a monastery on Inishmurray from the sixth century, abandoned in the twelfth century.

Charlie walked across treacherous seaweed-covered rocks and up past the ruins of the abandoned twentieth-century village, turning inland along the cobbled path leading to a fortresslike circular wall enclosing the religious settlement. The cashel wall is still fifteen feet high in places and ten feet wide, with only a narrow tunnel entrance leading through into the monastery enclosure. Guides from the mainland tell visitors the wall was built by monks as a defense against Vikings, but Charlie believes it pre-dates the monastery. If so, the monastery was built inside an earlier pre-Christian ring fort.

When Viking raids began at the end of the eighth century, offshore and coastal monasteries around Ireland were wide open to attack from the sea. "This was a peaceful, comfortable, and self-contained world for the monks," Charlie explained as he walked along the top of the cashel wall that circled the monastery. Inish-murray is unspoiled by tourism because it is so hard to reach. Stone beehive huts and other monastic buildings have hardly changed since Viking times, except that roofs were thatched then and much of the stonework painted. Outside the cashel wall, small dry-stone fenced fields worked by twentieth-century islanders are now overgrown with bracken and thorn. In the summer of 795 similar fields would have been full of ripening wheat and barley. In the haunted solitude of Inishmurray today, the ghosts of the past feel close— monks with their wives and children, slaves working the fields, monastery cattle grazing on whatever land was not either set aside for growing crops or useless bog; only a quarter of Inishmurray's land is free from bog today. A choir could have been chanting psalms in the church, tenant farmers singing more frivolous secular songs in the fields. Even if a sharp-eyed watcher had seen sails in the northeast, there would be no cause for alarm; island communities were used to seeing traders sailing up and down the west coast of Ireland. But then the Viking longships swept ashore on the narrow sand beach near the landing rocks and the killing would have begun.

"The attack must have been horrendous," Charlie said. "The people would have had no warning, no chance to defend themselves. Some would have been slaughtered immediately, most dragged off into captivity as slaves." If people inside had time to barricade the entrance, brawny Viking warriors could have boosted each other over the cashel wall to leap down inside, axes swinging as they hit the ground. In those first Viking attacks, surprise was a fearful weapon.

Standing on the same cashel wall more than twelve centuries later, it is not difficult to picture the scene: the monastery filled with smoke as thatched roofs are set on fire, dogs barking, pigs squealing, people screaming in fear and agony, the whole monastery swarming like an ant hill stirred with a stick. Once they realized what was happening, people out in the fields might have run back to defend their homes, their courage buying them only slavery or death. Most would have run away, hiding in the cave at the far end of the island where fishermen say monks always took refuge during Viking raids. The terrified survivors would have huddled together in the cramped hiding place, hushing the children to stop them from giving away their position, hearts pounding as they waited for the sounds of battle to fade and the raiders to leave. Only then would they dare creep back to tend the wounded and bury the dead.

By 823 Viking raiders had sailed all around Ireland. Many places on Ireland's south coast have Viking names, like the Blasket Islands in County Kerry and the Saltee Islands in County Wexford. Not even the jagged rocky crag of Skelligmichael—eight miles out into the Atlantic off the coast of Kerry—was safe, attacked in 824. It is hard not to admire the determination of Viking warriors who fought their way five hundred feet up hundreds of precipitous steps cut into the mountain to where the monks built their monastic village. Any monk with a stout quarterstaff would have had a good chance of knocking an attacker into the sea. Viking invaders were probably winded and angry by the time they reached the top. The annals record: "Etgal, abbot of Skellig, was carried off by the heathens and died soon after of hunger and thirst."

Coastal monasteries learned to dread the sight of sails on the horizon. Marginal comments scribbled on manuscripts offer momentary glimpses into these monk's states of mind as they waited fearfully in their coastal monasteries, praying for bad weather to keep shipborn raiders away from the coast. One monk, grateful for a howling Atlantic storm, wrote a poem in the Latin gospel he was copying:

The wind is fierce tonight

It tosses the sea's white hair

So I fear no wild Vikings

Sailing the quiet main.

Who were these Vikings? Why did they appear like a swarm of locusts at the end of the eighth century to plunder the coastlines of northwestern Europe? There is no simple answer, just a combination of economic and political factors that put the Norsemen in the right place at the right time. People in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden shared a similar culture, language, and religion during the eighth century, but there was no sense of unity between the various peoples of Scandinavia. The Svear kingdom (from which Sweden gets its name) was more interested in Russia and the rich markets of the Black Sea and the Eastern Roman Empire of Byzantium. Denmark, controlling lands in northern Germany, was preoccupied with the possible expansion of Germanic tribes into its territories. So it was the Norwegians, fragmented into more than a dozen petty chiefdoms and geographically isolated by mountains and impenetrable forests, who first seized the opportunity to trade and plunder across the North Sea in Britain and Ireland at the end of the eighth century.

The people of Norway were farmers and fishermen, traders and explorers, ruled by local warlords hungry for wealth and plunder but with scarcely enough men and resources to outfit even a single longship. Even the wealthiest warlords at the start of the Viking Age would have owned no more than three or four such ships. Yet it was the longships that gave the Norse their great strategic advantage during the Viking Age. Based on earlier Germanic boats, Norse seamen had perfected the design through centuries of sailing in the treacherous fjords and storm-tossed seas around the Scandinavian coasts until they had developed into Europe's finest warships.

Viking dragon ships—so called because of their carved prows—probably only reached their final form in the mid-eighth century, a case of the right tool being ready at the exact moment conditions were right for its use. They were the foundation of Viking power and the most treasured possession of any Viking warlord. Kings and chiefs were often buried in them, which is why so many boats have survived. The best known was excavated in 1880 at Gokstad in Norway and is still on display in a museum in Oslo; seventy-seven feet long and almost eighteen feet wide, its keel is carved from a single tree. Viking ships had planking that was tied— rather than nailed—to the ribs so the entire boat could flex and bend in heavy seas. The Gokstad boat was built for thirty-two oarsmen—sixteen on each side—but was fitted with thirty-two shields on each side, suggesting it might have carried a double crew to allow rowing in shifts. It shipped a forty-foot-high mast, holding a square sail that would have given it a top speed of more than nine knots in a good wind.

The chieftain who owned this mighty machine of war was buried on a bed at the stern, surrounded by everything he would need in the next life including weapons, clothes, tools, twelve horses, and six dogs. This was a ship for fighting and trading, possibly able to carry as many as sixty-five warriors all the way to Ireland and beyond. Other trading ships were wider and deeper, capable of carrying more cargo but less effective for hit-and-run attacks on a hostile shore.

The first raids would have been tentative. The Norse would not have known what to expect in Ireland, but word would quickly have spread that Ireland was ripe for the plucking. Vikings from Norway continued to be the chief threat to Ireland through the middle of the ninth century. Denmark was more interested in Britain and did not become involved in Ireland until later. Fleets grew larger as more powerful and ruthless Norwegian warlords brought lesser chiefs under their control. Monastic raiding was a growth industry, a gold rush for Norwegian nobles with households of quarrelsome and warlike sons. The Vikings were a vigorous and fast-breeding warrior race in a harsh land where plenty of strong sons were proof of a man's virility. The eldest son inherited the family land; younger sons were expected to find their own. Since so much of the country was mountainous, there was a severe shortage of good farming land, and fights over inheritance must have been common. Many a frustrated local chief may have outfitted a long-ship, packing his sons and followers off with instructions to "Raid west, my sons," just to get a bit of peace and quiet at home. More likely, being a good Viking, he would have led the raid himself, crewing his longship with sons, family, and retainers, and taking his "spring" or "summer" cruise when several months of good weather could be expected before approaching winter brought the Viking chief and his sons back home. There he would spend the winter surrounded by his family and slaves, drinking and feasting and boasting of all the battles he had fought and the treasure he had seized in the lands around the Irish Sea. And every spring as the weather improved, Irish monasteries braced themselves for raiding season.

For much of the century prior to the first Viking raids, Europe was getting itself organized after the barbarian invasions that caused Rome's fall. New nations were forming, new dynasties consolidating power. The people of Scandinavia had been traders for more than a thousand years, shipping furs, amber, slaves, and ivory— from the tusks of walruses—south to the Mediterranean since before the Roman Empire. But the Dark Age was not good for business. Trade routes had been disrupted as Germanic tribes spilled out of the east in the fifth and sixth centuries to establish new homelands in Italy, France, Spain, and even North Africa. Ancient Roman cities were either destroyed or in decline.

By the eighth century, a new stability was being imposed on Northern Europe by a Germanic tribe known as the Franks. Further south, Muslim armies from North Africa had conquered Spain, moving deep into France and seizing Sicily to dominate the south of Italy. For a thousand years Europe's heart had been the Mediterranean world of Greece and Rome, but now the Eastern Roman Empire of Byzantium was a shadow of its former self and the Mediterranean was a Muslim lake. In the north the Franks were ruled by the Carolingian dynasty that was building a new Christian civilization. When the pope crowned Charlemagne, king of the Franks, as head of a new Holy Roman Empire in 8oo, it was confirmation that the Frankish kingdom of Northern Europe— today's France, Germany, and a whole lot more—was the new center of European power. Trade routes were open again, and business was booming. Viking traders returning home to Scandinavia from lands in the south must have brought back plenty of stories about the wealth of Christian monasteries and the opportunities for plunder and settlement they had seen along the way.

Piracy, trade, and land-grabbing were inseparable to Vikings. They were pragmatists, trading with people stronger than themselves, carrying off anything that was not nailed down where coastal populations were weak. Slaves were the richest prize of all. Like other warrior cultures, including the Irish, Norse society was divided into three classes and life was defined by the class into which you were born. At the top of the heap were the ruling military aristocrats, called jarls—from which we get the English "earl." These were kings and nobles, warlords with sufficient resources to outfit and crew longships. Next came the freemen, called karls—warriors, farmers, and tradesmen, equivalent to our middle class, the backbone of society. Last and absolutely least were slaves and serfs, called thralls, who had no rights whatsoever and did all the hard and dirty work.

Vikings were the greatest slave traders of their age. Herds of human cattle were rounded up and brought back to slave markets scattered throughout the Viking world, then sold on south into Byzantium, Persia, and the new Muslim Empire. The slave trade was the cornerstone of all Viking commerce, and no Viking household could survive without slaves. Slaves worked the fields, harvested the grain, and if young and attractive warmed the warrior's bed at night. When Vikings settled Iceland at the end of the ninth century, thousands of Irish slaves were brought over to do the hard labor.

Monasteries were the major centers of population in ninth-century Ireland. They must have seemed like supermarkets of opportunity for Viking warriors out to make their fortune. Here were hundreds of potential slaves gathered conveniently in one place, with monastic treasure as an added bonus—silver and jeweled chalices and reliquaries that held the bones of saints. Chalices and shrines were melted down for raw silver or taken home as family souvenirs while books and manuscripts were burned or tossed aside in the mud, worth nothing to illiterate pagan raiders. A British monk at the court of Charlemagne in Germany declared the Vikings an instrument of God's anger, punishing the people of Europe for their sinful ways.

Longships ruled the Irish Sea and Vikings were the greatest sailors of their age, but it is easy to forget how desperately vulnerable they were to being blown off course or sunk by storms and heavy seas. Sailing the Viking sea lanes today in a modern warship, with position fixed by satellite navigation, computers tracking course and speed while charts and sonar identify unseen rocks, is a far cry from Viking sailors who navigated by the feel of the sea and the sky, an instinctive understanding of currents and tides, the smell of the wind, and the position of coastal landmarks and the stars. How many ships were lost? How many more Viking warriors were drowned than were ever killed in battle?

The Roisin is the Irish Navy's newest ship, a high-tech warship for the twenty-first century just as longships were for the ninth century. At 258 feet she is more than three times longer than the Gok-stad boat but carries a smaller crew. Tom O'Doyle, Roisiris captain, had invited Donnchadh Ó Corráin and Pat Wallace aboard to follow a Viking trade route up the east coast of Ireland from Cork to Dublin. Pat is one of Ireland's most respected archaeologists. In the 1970s and 1980s he spent seven years directing the excavations of Viking Dublin.

On a blustery wet summer day—typical Irish weather—with the sea high and the waves white with foam, Pat and Donnchadh stood on the Roisin's bridge, hanging on grimly as the warship rode each crest only to slam down into the next trough, and spoke of the Viking ships and sailors who sailed the same seas twelve-hundred years earlier. "The ships were flexible and had a very shallow draft, useful for running up beaches or traveling up-river, but they wouldn't get a good bite of the sea," Pat explained. "They'd be pretty unstable with such a big sail and very top heavy, so if they went over, it would be almost impossible to get them right side up again. A terrible number of Viking ships must have been lost."

How easily Viking longships capsize was proved in recent years while a British television crew was making a program about Vikings in the North Sea. The reconstructed longship swung crosswise into the wind and flipped over in just a few seconds, too fast for anyone to do anything except swim for their lives. No one was hurt, although a lot of expensive TV equipment ended up at the bottom of the sea. Vikings were not so lucky. As Pat said: "Some ship archaeologists believe at least half the Vikings were lost at sea, even though they were by far the best navigators of their day."

Captain O'Doyle took a pragmatic seaman's view. "Safety and comfort wouldn't have been a consideration. The ships were designed to transport warriors to a particular location quickly and effectively." It was a strange conversation to have on the high-tech bridge of a modern warship. The shore was less than a mile away, a rocky headland looming out of the drizzle and framed by white-capped waves. In the distance white breakers crashed against the base of a gray cliff, yet the two scholars aboard the Roisin sailed into the rising storm inside a warm protected bubble.

"The cold would be deadly," Pat said. "You'd be wrapped up in furs, but you'd be soaked to the skin half the time. And the smells! The sail was dipped in boiled horse fat—can you imagine the stink of that on a sunny day when you're trying to pick up a breeze in the North Atlantic?"

Colmcille's monastery island of Iona was particularly vulnerable to attack from these sea-raiders since it was off the west coast of Scotland, directly in the path of any Viking longship heading south to Ireland. By the ninth century it had become the center of a great federation of Columban churches spread out from Ireland to Scotland and northern Britain. Lindisfarne in Northumbria, site of the first Viking raid in 793, was part of this federation. Baided in 795, Iona was burned in 802 and again in 806, when sixty-eight of the community were killed by "the heathens" and many more taken into slavery. Quite obviously something had to be done. In 807 the annals record "building a new monastery of Colmcille at Kells." Kells had been a prehistoric Irish kingship site and was now a royal hill fort belonging to the Southern Uí Néill. It had the great advantage of being twenty miles inland, safe from marauding Vikings who in the early years never went too far from their ships. Seven years later the new monastery was complete, and Iona's abbot resigned and left the island, presumably to head the new monastery at Kells. For the next fifteen years Kells and Iona continued to be governed as a single community.

The Book of Kells is the greatest and most famous medieval illuminated gospel manuscript in the world, named for the monastery at Kells where it remained for so long, but scholars still argue about where it was made. Most think it was likely created on Iona, perhaps commissioned for the two-hundredth anniversary of Colmcille's death in 597. It would have been one of the most precious treasures of the monastery. And as Viking attacks grew more frequent, it must have been brought to Kells soon after the refuge was completed in 814.

It is tempting to think of Iona's abbot, saying goodbye to his fellow monks and walking down the beach below the abbey to where a hide-covered currach would be waiting to carry him back to Ireland, clutching the precious manuscript wrapped in animal skins to protect it from the salt water. Rowing out into the narrow channel between Iona and the larger island of Mull, the abbot and his crew would have pointed their bow south and raised the sail, making a run for the Deny coast of northern Ireland more than seventy miles away, no doubt praying that they would not run into Viking raiders along the way. There is no way of knowing if the Book of Kells was on Iona in 814, but the fact that the manuscript is unfinished supports this image of a great work of art being bundled up and carried out of reach of Viking raiders to the sanctuary prepared for the monks and precious relics of Iona.

Iona was not abandoned. The Vikings hit it again in 825 and murdered a monk called Blathmac and many of his companions because they refused to reveal the location of a valuable shrine said to contain the bones of the founding saint. As a later abbot brought Colmcille's bones back to Iona from Ireland in 829, there may have been different sets of saintly relics. As for Blathmac, it is said he came to Iona in 818, hoping for martyrdom at the hands of the Vikings. If so, it must have been frustrating to wait seven years before he got his wish.

History is usually written by the winners, but in Ireland it was victims who kept the records, which is why Vikings always got such bad press. Irish kings had been raiding each other's monasteries for centuries. Even in the middle of Viking raids in 833, Feidlimid—the bishop king of Munster—killed monks at Clonmacnoise and burned their lands "up to the doors of the church" because the monastery was allied with the Uř Néill, his rival for the largely symbolic high-kingship of Ireland. Vikings were not doing anything new, but they were foreign and pagan, which meant that everyone hated them, the "sea vomitings from the north" as they are described in the monastery annals. Terror may also have been a deliberate tactic, convincing victims to surrender quickly rather than resist. Outfitting a Viking raiding party was expensive; healthy slaves get a better return on investment than dead bodies.

Annals offer a detailed if one-sided view of the Vikings in Ireland. Mostly they call them heathens, sometimes Norsemen or foreigners, and they make a clear distinction between "white foreigners" from Norway and the "dark foreigners" who arrived later from Denmark, which probably relates to a difference in dress between Norwegians and Danes. From 795, when the annals record the first attacks on Ireland, through the late 820s, the records show an increasing pattern of attacks around the coast, sometimes going a short distance inland but never so far that the raiders could not return quickly to their boats if they ran into heavy opposition. Sometimes the invaders were beaten off, as in 825 when they were routed by the Ulaid—the men of Ulster—but usually the story was a litany of monasteries burned, abbots, kings, and local leaders killed, and men and women taken into slavery.

The annals were not concerned only with Viking raids. They also provide a record of everything else going on at the time, from the succession of abbots and the dynastic wars between Irish kings to occasional glimpses of everyday life at the beginning of the ninth century. The winter of 822 was apparently so cold that "seas, lakes, and rivers" froze hard enough for wagons, cattle, and horses to travel across the ice. The following year the abbot of Armagh's house was struck by lightning—"fire from heaven"—and burned to the ground. Travelers moving from monastery to monastery brought news of what was happening around the country. Local and regional kings were probably well informed about Viking raids but initially saw them more as a nuisance than a serious threat, getting involved only when raiding occurred in their own backyards. Irish kings probably hired Viking warriors for their internal wars quite early, and the Vikings themselves had no sense of common purpose at this time. They were in it for the money. As Pat Wallace said, "Even though they shared a common language and culture, they were all different, warring with each other, just hit men, raiders, and traders, making alliances with certain small Irish kings against other small Irish kings, capitalizing on weaknesses all the time."

By the 830s this first casual raiding phase was over. Viking attacks on Ireland became much more serious once they started moving inland.

Raiding coastal monasteries had reached a point of diminishing returns; populations were growing wary, hiding themselves and their valuables at the first sight of a sail. Vikings knew much more about Ireland by this time. They had spent thirty years exploring the Irish coast, long enough to learn some Irish while many of the locals would have picked up enough Norse for communication. The Vikings had learned that the real wealth of the country was in great inland monasteries like Durrow, Cork, Armagh, and Clonmacnoise. They certainly knew that many of Ireland's rulers were preoccupied with a dynastic dispute between the Uí Néill and the Eóganacht kings of Munster over the high-kingship.

These were the years when the Vikings made serious gains in Ireland and came close to overrunning the whole country, as they would in Britain, Scotland, and northern France. Between the 830s and the 850s, fleets were bigger and better organized, sailing up the rivers and lakes to strike deep into the heart of Ireland. Vikings were no better or worse warriors than the Irish, but their mobility— and initial lack of fixed bases vulnerable to counterattack—gave them an edge. Along with shallow-drafted longships carrying them far inland, the Vikings were also great horsemen. Back home in Scandinavia a warrior's horse was often buried with him. Raiding parties would have commandeered horses as soon as they landed and covered great distances as mounted infantry. Counting on surprise and speed, they would often be gone with their slaves and treasure before local troops could be organized against them. But there must have been plenty of times when it became a race back to the boats, Vikings hurrying their terrified captives at sword-point, killing any who slowed them down, while Irish warriors panted at their heels like hounds chasing a fox. When Vikings did face another army, their usual tactic was to lock their shields together into an almost impenetrable barrier called a shield wall. Since Irish warriors used similar tactics, battles could become stuck in a stalemate of shield wall against shield wall, each shoving and straining to break the other's line. Elsewhere in Europe there are descriptions of this going on for hours until finally, like water breaking through a dam, one side would either break or run and the slaughter could begin.

In 832 Armagh was attacked three times in a single month. "They'd found out about Armagh when they plundered some dependent churches on the coast the year before," Donnchadh Ó Corráin said. "Armagh sent a military force which was defeated. No doubt they had a little chat with their prisoners and learned how things worked. It wouldn't be difficult to figure that Armagh would be packed with pilgrims on March 17, the great feast of St. Patrick. They'd know it was the best time to attack." Armagh was always a popular Viking target, and the annals tell of one thousand prisoners taken in a single raid. The fact that Armagh continued to survive indicates just how large a population it could support.

The five years between 836 and 841 were particularly bad for the people of Ireland. Feidlimid, the Eóganacht king of Munster, and his Uí Néill rival were at each other's throats, and the Vikings chose this time to launch their deadliest assaults—hardly a coincidence. In 836 they struck inland from present-day Galway to devastate the lands of Connaught, and sailed up the River Shannon into the heart of Ireland. Unlike most Irish rivers, which are fast flowing and difficult to navigate, the Shannon is a long, lazy waterway that opens out into great lakes—Lough Derg and Lough Ree—ringed by rich and powerful monasteries like Killaloe, Holy Island, Terryglass, Clonfert, and Clonmacnoise. Once Viking ships were on the lakes, the fox was loose in the henhouse.

"Clonmacnoise was the greatest of the monasteries on the Shannon, a center of European learning," Pat Wallace said. "But there were no buildings on the site taller than a Viking ship. So when a fleet of dozens of ships came up-river, each one of them towered like a jumbo jet over that whole town. It put the fear of God, literally, into these men of God."

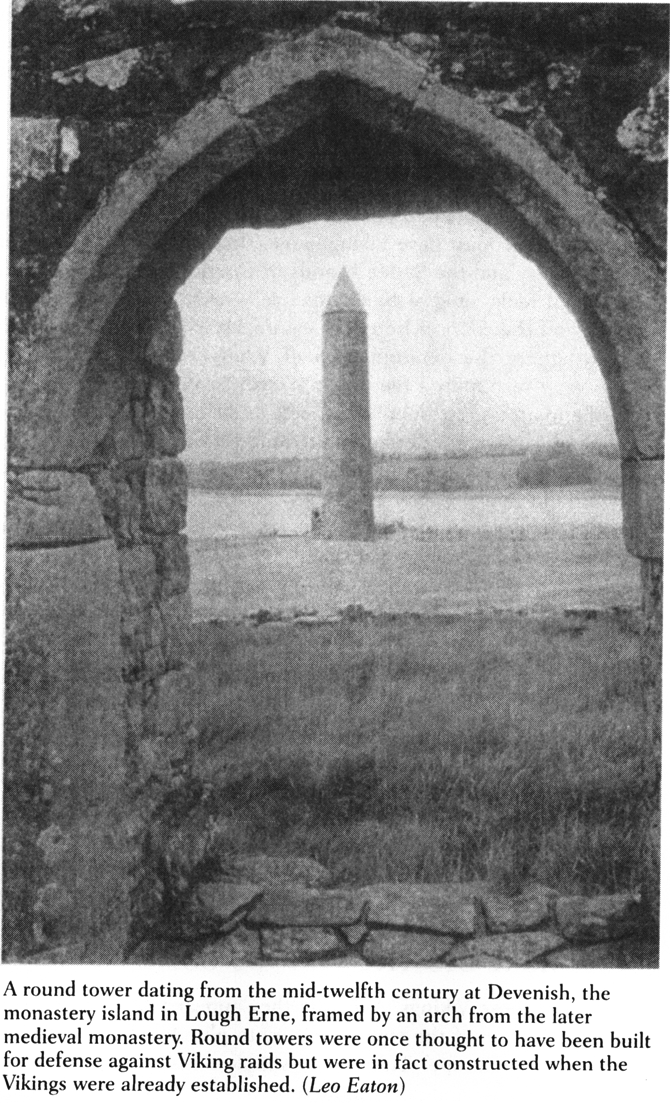

In 837 a raiding party came from Donegal Bay in the northwest to penetrate into Lough Erne, raping, and looting the monastery of Devenish along the way. But the most important development occurred that same year when two fleets—with 60 ships each—appeared on the Boyne and Liffey rivers in the east, putting the rich Uí Néill heartlands of Meath—and Tara itself—within reach. If each ship carried a minimum of 30 warriors, two fleets together could have landed more than 4,000 men, a considerable force by the standards of time. Fighting was heavy all through the following year. Annals record that 120 Norsemen died in one battle but that in another the Uí Néill army was defeated and an uncounted number were slaughtered, though the principal kings escaped.

If the two fleets on the Boyne and the Liffey arrived together, as seems likely, such a sophisticated joint action would have required time and planning to assemble the necessary ships and men. Donnchadh Ó Corráin believes that a powerful Viking dynasty from Norway had already established an independent kingdom in Scotland by the 830s, comprising parts of the mainland as well as the Northern and Western Isles. Their intelligence about conditions in Ireland was probably excellent. In 839 another fleet attacked Ulster, following the river Bann into Lough Neagh and then continuing south to Armagh. Later legends suggest a Norwegian warlord called Tuirgeis led the raid. He supposedly arrived in the north with a large fleet in 839, made himself "king of all the foreigners of Ireland," attacked Armagh where he "celebrated pagan religious rites on Patrick's altar," settled Dublin the following year, and was finally captured and drowned in Lough Owel in 845 by the king of Meath. Unfortunately there is no evidence to support the idea of an overall Viking leader in Ireland at this time.

Tuirgeis was turned into a bogeyman in later times, a name to frighten small children and a favorite target of Christian propaganda against the "vicious Vikings." Undoubtedly actions of different Viking leaders were attributed to him, just as stories accumulated around famous Christian saints, yet he was clearly an important leader. Only two Vikings are mentioned by name in the annals from this period. The first is Saxolb—described as "chief of the foreigners"—who was killed by the men of Connaught in 837, the year after Viking raiders plundered the province. Second is Tuirgeis, whose death is reported in 845, confirming his importance. In 845 annals note that there was "a great encampment of foreigners on Lough Ree," who plundered west into Connaught and east into Meath. Since Máel Sechnaill—the king of Meath— took Tuirgeis prisoner that same year and drowned him in a lake less than twenty-five miles away from Lough Ree, it is logical to assume he was one of the leaders—if not the leader—of this invading army. By the 840s, raiding had become full-scale invasion. Ireland's future would turn on the actions of the man who drowned Tuirgeis. In 846 the king of Meath—Máel Sechnaill—became rule of the Uí Néxill and so high-king of Ireland.

During the first decades the Vikings were in Ireland, they sailed away each year as winter approached, returning either home to Norway or to settlements in the Scottish Isles. There is no telling exactly when they started wintering in Ireland, although as early as 828 annals describe "a great slaughter of porpoises by the foreigners" that might indicate laying in food for a winter stay. Charlie Do-herty thinks it likely the fleets on the Liffey and Boyne in 837 remained through the winter, but the first real evidence of Viking settlement in Ireland comes four years later. In 841 the Annals of Ulster report that two naval camps were established by the Vikings at Duiblinn (Dublin) and Linn Duachaill.

Each of these camps was situated on the borders of warring Irish kingdoms, strategically placed to dominate Ireland's agricultural heartland and several major routeways across the country as well as Tara itself, the symbolic heart of Ireland situated halfway between the two camps. Linn Duachaill is about 60 miles north of Dublin at the village of Annagassan on Dundalk Bay. These were not accidental choices, so it is likely the campaign was again planned and coordinated from the Viking kingdom in Scotland. Leaders of the colonizing fleets would have been expected to swear allegiance to the king. When a much bigger fleet of 140 ships was sent eight years later by "the king of the foreigners to exact obedience from the foreigners who were in Ireland before them," it is clear Irish Viking leaders had forgotten who was supposed to be running the show.

The naval camps at Dublin and Linn Duachaill were called longphorts, fortified camps where the longships could safely be hauled up on dry land for repair over the winter. Earth banks and wooden palisades, much like Irish forts of the period, would have protected houses and a landing place for the fleet. Archaeologists have not yet found the exact location of the first two Viking settlements in Ireland, but there is no shortage of theories. Historian Howard Clarke suggests that Vikings first settled at or near Irish monasteries where existing infrastructure and possible Irish allies would have made things much easier for the newcomers. The abbot of the monastery at Linns (Linn Duachaill) on Dundalk Bay was killed by "heathens and Irish" in 842, perhaps because he objected to what was going on, so the monastery was clearly still in operation. The monastery of Dublin had been built on the banks of a tributary of the Liffey called the Poddle. Just before it emptied into the mouth of the Liffey, the Poddle widened into a natural harbor known as the Black Pool—in Irish Dubh Linn. Such an existing monastery with a good anchorage was probably useful at the start but not necessarily ideal for a more permanent longphort settlement. Annals in 842 record "the heathens still at Duiblinn" but by 845 there is mention of an encampment of foreigners at Ath Cliath—the Ford of the Hurdles—probably a couple of miles upstream on the Liffey where an island in the river—later called Usher's Island—might have been easier to defend. Ath Cliath was the main Dublin settlement on the Liffey for the next eighty years, a sprawling trading camp whose main business was slaves captured in raids up and down the country. The Vikings had come to Ireland to stay, but settlements such as Dublin and Linn Duachaill also made them vulnerable. Irish kings had awakened to the fact that their own power was now threatened. The next dozen years would decide who controlled Ireland—the Irish or the Vikings.