{1}

Prelude

After a lapse of nearly twelve years, I finally went to see U.G. Krishnamurti again in January 2002. Every year the news of the arrival of this strange ‘bird in constant flight’ in Bangalore would somehow reach me, but I wouldn’t feel the urge or curiosity to go and see him. There seemed no need to go and greet him or listen to his reproaches. But then, I would also tell myself: hasn’t he become a part of me, a vital part of my consciousness? Is there really any way of getting away from him?

Perhaps there was another reason for not having kept in touch with him. Maybe I was afraid! I had had enough of him—enough of these two Krishnamurtis. If J. Krishnamurti had tried to skew my spiritual search and puncture my hope of attaining moksha, UG had destroyed the very ground on which I had still been struggling to carry on my search somehow. There seemed no point to it at all. It was all futile. This search, this yearning, almost literally like searching for a needle in a haystack, or like looking for a black cat in a dark room, or was it more like chasing one’s own shadow? It was not just unproductive or uncreative, it seemed positively harmful.

‘I can’t help you,’ UG had warned again and again. ‘Nobody can help you, and you can’t help yourself either.’ In fact, there is nothing there to search for, to attain, he had added. And then finally, destroying all hopes, he had warned yet again: ‘Your very attempt to become something which you are not is what makes your life miserable. Your very search for freedom creates its opposite and takes you away from it, that is, if there is such a thing as freedom at all.’

Indian spiritual traditions teach that not by wealth, not by progeny, but by renunciation alone is immortality attained, and you are advised that renunciation can be taken up after completing the life of a student and a householder. However, Yagnavalkya says in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad that the very day when one becomes indifferent to the world (samsara) or comes upon a sense of disgust with life and the world, one should leave and become an ascetic.

Even as a student I had felt this disgust. I was not even twenty, but I had already started thinking of myself as a spiritual person born for higher goals. I spent most of my time outside the classroom, in public libraries and at the Ramakrishna Ashram library situated near my college, studying religious texts and the lives of spiritual masters, and again in the evenings, at home, I would immerse myself in reading or making notes from religious books. Since ours was a large family of five brothers and a sister, and there was hardly any quiet corner to meditate, I would sit in the open field in front of our house and meditate as long as I could, or gaze upon the heavens until tears streamed out of my eyes.

Inspired by Gandhiji’s life and ideas, I tried to lead a simple life. I wore khadi trousers and shirts, rubber slippers, and avoided sweets, stimulating beverages, and girls. I believed I was spiritually ripe enough to enter into a full-time adhyatmic or spiritual life. I had no doubt that I was another Vivekananda in the making, who would soon burst upon the world and deluge it with ennobling spirituality. I believed I was born to understand the secret of existence, understand and experience the ultimate Brahman and with Brahmajnana transform the world into a realm of ananda, a new age, the age of transcendental consciousness!

The whole thing sounds like a weird joke or a funny story today. However, it was during that time and in such a frame of mind that I first heard J. Krishnamurti speak. It was in the 1970s, on a summer evening at Lalbagh in Bangalore. I had no clear idea of his teaching, just that he was a spiritual teacher of extraordinary quality.

Silhouetted against the trees, lit up by the setting sun, he sat on a small platform. A fairly large crowd, mostly men, sat still, eager, expectant; the rock behind us still radiated heat, and on top of the rock stood a mini tower like a witness, erected some 465 years ago, to mark the border of Bangalore.

The effect of J. Krishnamurti’s (JK) talk on me was devastating, to say the least. I do not remember how I walked the sixteen or eighteen kilometres home. It was past midnight when I lay on my bed. I was on fire and there was this terrible anger, yet a strangely profound expectation. Suddenly mountains were not mountains, rivers were not rivers, the sky was not blue any more than blood was red, and people did not seem to be what they appeared to be. In short, nothing was what it seemed to be. Yet, for the next few years I went through the motions of my academic studies and daily routine like an actor, all the while with this peculiar awareness that all this was but a hugely entertaining yet painful drama, a grand lila that Brahman was playing through me.

‘Awareness’ became my mantra, and I felt a constant burning from my head to my toes. Every object, every face seemed like the centre of the universe. And I walked around in the full glare of the seven worlds, as it were, like some naked Digambara.1 Friends, relatives, even parents eyed me with awe and respect, yet not without some misgivings.

In the second year of my BA course (with philosophy as one of my optional subjects), I left home and visited Swami Chinmayananda at Trivandrum. I had written to Swamiji, ‘I am ready . . . Who can stop the blossoming of the flower, who can stop . . .’ and was truly prepared to jump into the sea if he asked me to. Smiling through his handsome beard, Swamiji said that it was absolutely necessary for me to complete the BA course and acquire some worldly knowledge and skills before I embarked upon sanyasa. I was heart-broken. It was like being jilted by the one you loved most. From there I went to Pondicherry. The white skins and the garrulous Bengalis at the Aurobindo Ashram made me feel like a foreigner. Auroville, supposedly an international city, looked incomplete and hopeless, and it seemed to me that any spiritual sadhana in this place, drained of all energy after the death of the Mother, was doomed to fail. And from there the trip to Ramana Ashram at Tiruvannamalai only completed my disillusionment.

However, in the final year of my BA course, I again went to Sandeepani Sadhanalaya in Bombay. Swami Chinmayananda was then touring the Western world. The second-in-command, a no-nonsense Vedantin, Swami Dayananda, saw that I was deadly serious. He suggested I relax for some days and feel things out before I took the final plunge. But JK wouldn’t let me relax before taking the final step. His iconoclastic ideas were playing havoc with my mind, and I began to think that a genuine search for truth could not be transacted within an already established pattern of life and study and sadhana in an ashram; that truth, if it could be found at all, wouldn’t be inside a conventional religious order or tradition, however good and profound. For there was no genuine search there, only a trained confirmation of answers to all questions already given by tradition. After ten days of deep contemplation, terrible confusion and misery, I left the ashram, returned home and sat for the final BA examinations.

Soon the disgust with the world changed into disgust with everything spiritual. The post-graduate course in English literature brought me down with a thud. I thought ambivalence in life was only human and natural; conflict was the stuff of dualism, and without dualism there could be no art, no music, no love, no samsara, and no search—so why not play along in this world of maya, and see how it goes!

Literature worked as a catharsis, at once a way out and a way into life. Then came love and marriage, profound discoveries and transformative experiences. To know one person intimately and deeply was to begin to understand oneself and humanity. One learnt also that there was no love without desire, and desire, I realized to my horror, operated always within the domain of power. If there is to be love which is not the way of power, then desire and expectations have to come to an end; perhaps only then would there be true understanding and the blossoming of true love. But is it possible? Wouldn’t it be like burning one’s boat in the middle of the sea?

The spiritual seeker turned into a man of samsara, and into a helpless writer. Still, to quote from the last part of my first novel: ‘With all this, I must admit, I feel this volcanic burst within me: there is this sannyasi still alive, kicking, restless, contemplating; licking moksha cream, insatiable, burning and exploding with fury, and with one sweep whacking the whole universe into one big zero . . .’2

The very first meeting with U.G. Krishnamurti shattered me. I realized that JK’s ‘pathless path’ had crystallized into a path in me. It was truly hopeless. The very search for truth seemed absurd and an exercise in futility, for all efforts to reach a goal only took one further away from the goal. As UG would say, it is like the case of a dog and his bone. The hungry dog chews on a lean, dry bone, and doing so hurts his gums and they bleed. But the poor dog imagines that the blood that he is savouring comes from the bone and not from himself. It was fairly simple and clear. The problem lay in the so-called solution! Rather, the solution was the problem. The answer was already there in the question. And the question was me, myself.

One day, while sitting in a public library at Cubbon Park, Bangalore, I experienced a great, terrible fear. Everything around me blanked out and I felt engulfed by some great darkness. I could almost touch it. Then I began to descend into some sort of a bottomless pit. It was most frightening. I felt I was going to die, but even in that state of terrible fear, I thought it would be embarrassing to fall dead in a public library. This ridiculous thought seemed to have brought me back to my ‘normal’ consciousness. I do not remember clearly what happened later. Perhaps it was something brought on by my hunger or mental fatigue, or I don’t know if I missed my bus that day!

For the next eight years I met UG every time he came to Bangalore. I wrote two fairly ‘comprehensive’ articles about UG for newspapers in Karnataka. It was a sort of cathartic exercise, futile though it was, to get him out of my system. I stopped meeting him and then I let myself plunge into life.

I started working on a novel and tried to get on with my married life and teaching at a college. I worked with NGOs and got involved with issues concerning women, the caste problem, communal conflicts, and human rights. Some of my friends had travelled a different path. They had started with radical politics and moved towards spirituality; I had started with spirituality and then come round to politics and uncertainties.

Twelve years. Life was all on the surface. It was all there: ambivalent, enigmatic, too complex to arrive at any clarity of understanding. Two children. Four books. A play. More than twenty years of teaching. A trip to Cambridge. Greying beard. Ageing parents. Several wars. Communal riots. The demolition of Babri Masjid. Assassinations. Farmers committing suicide. Terrorism. India going nuclear. Pakistan going nuclear. Multinational corporations beginning to take control of the world. The gargantuan wheel of globalization rolling on. The world ruled by politicians and scientists who were out of control. Fear uniting the world. The death of politics. Terror and violence, a seamless whole, connecting religious groups with political parties, secret agencies with fundamentalists, and business industries with the mafia, and all springing from the same source, from the same ideology of control and power over the world. The search for alternatives, for different, peaceful, non-violent and non-exploitative ways of doing and being gained urgency, but there was no conviction or strength. It seemed there could be no new creation without destruction, but there was the terrible lurking fear, that there would be nothing left to create after the destruction. UG arrived in Bangalore. Twelve years had gone by. It was time to go and meet the sage in rage, the cosmic Naxalite.

That’s how, that afternoon, along with a doctor friend and a young German who was visiting Bangalore, I went to see UG. Since the doctor was not feeling too well, the German friend drove us through the heavy evening traffic. He drove like an expert BTS bus driver. ‘You drive quite well,’ I remarked. ‘Yes . . . people here respect big vehicles,’ he quipped. It was a Tata Sumo, big, heavy and intimidating! Smaller cars quietly gave way, and on seeing the monster coming, pedestrians thought twice before crossing the road. He had read some J. Krishnamurti and was going to see UG for the first time. The air was heavy with pollution and the usual din of the evening. I was not sure what I would feel at seeing UG, nor whether he would even recognize me. I reassured myself that I was just going to meet an old friend. No questions, no interrogations, just a meeting with the most wonderful yet intriguing human being I have ever known. Such were my thoughts.

It was one of those well-planned, government-sponsored layouts, with tarred roads, underground sewage and parks. And it looked like a typical middle-class house with potted plants along the compound wall and just enough space for a car in the drive, but the portico was strewn with slippers and shoes. As we stepped into the brightly lit sitting room, we saw about thirty people sitting, most on mats, a few on chairs and sofas, and there on a long sofa pushed against the wall, sat the figure in white, like a huge, distinctly unique pigeon among birds of varied hues. His hair, grey and flowing, had thinned. The face, fair and lined, surprisingly looked not much older than what I had imagined. He returned our pranams and we sat on a mat. The atmosphere was not like what I had experienced in the past (though in a different neighbourhood and a different house). I was particularly struck by the large number of young men and women ; they looked trim, fresh and relaxed. They smiled, laughed and shot questions at UG with ease. The people I used to be familiar with were sombre, hesitant and profoundly respectful. Indeed they were there even now, all full of concentration or in some deep cogitation. There was a sanyasi too, in ochre, a young one with chubby cheeks, almost a boy, who kept restlessly shuffling from the hall to the room to the portico and back. A few foreigners too, from France, Germany and Israel. A stout Jewish woman seated on a sofa was busy making notes in her scrapbook.

I looked again. UG looked much older now, but certainly not like someone who has lived on this planet for eighty-four years. The incredible charisma was still there, the same grinning lips and unblinking eyes, and that enchanting glow that radiated from the whole of his body. And the voice: unmistakably straightforward, curt, harsh, and at times even abusive. And his humour—tongue-in-cheek, sardonic, acerbic, devastating yet eliciting peals of spontaneous, indulgent, nervous laughter from the small crowd.

The host, Chandrasekhar, asked, ‘UG, don’t you remember the professor? Twenty years ago, he had written two articles on you!’

UG did not remember. But soon, in response to another question, he started, in lighter vein, recalling his days in America, his wife’s little adventures while working in a library there, his eloquent speeches which had been reported with high praise in prominent newspapers. Then the inevitable happened. The free-flowing words fell like soft pebbles and tickled the crowd into giggles and guffaws. Nobel Prize winners were brought down from their heights, gurus were torn to pieces, shibboleths of all grand and noble ideas were smashed to smithereens.

Was Mother Teresa a lesbian? So what? Hadn’t she been a godsend, giving succour to thousands who faced a miserable life and death? And then how could one belittle the extraordinary personality of the Dalai Lama? Isn’t he one of our central symbols of peace, non-violence and compassion in a world beleaguered by violence and corruption? I did not open my mouth. Some of my activist friends would have been scandalized and feminists would have been outraged. But then UG has never been either gender-sensitive, nor politically correct. He has been crude, politically scandalous, delightfully wicked and religiously blasphemous. Almost all the central symbols of various religions and cultures, all major ideologies and philosophies were subverted or dismissed as so much garbage. If there was a God and if He were to make the mistake of walking into the room now, even He would have been roundly abused, ridiculed and laughed at, and then mercilessly butchered. There was nothing sacred or sacrosanct, nothing unquestionable and incontestable there. Subversion was the way of thinking. And then subversion too was subverted and demolished.

A little later, maybe because only a few minutes before UG had talked of ‘divine thoughts’ and ‘bouncing breasts’ in the same vein, a young man, neatly dressed, his back erect, and much inspired, asked, ‘UG, can you have sex?’

A ridiculous question for a man of eighty-four! With an oh-mygod smile, UG held up the tip of his forefinger. ‘There is nothing here,’ he said quietly, ‘that says I am a man, I am a woman, or that I am an Indian . . .’

There was, of course, the irrefutable biological fact of UG having fathered four children. That was in the past, before the ‘calamity’. No thought now stayed long enough for any sense of identity to build up and continue, thoughts which were essential for sexual excitement, in fact all thoughts got burnt. That was UG’s song. Now, all of a sudden, in the middle of this ‘indecent’ conversation, he bangs the wooden teapoy with his fist several times. Thud, thud-thud . . . the sound fills the now silent space, and he thunders, ‘There is no interpretation of the act. There is nothing here that calls it soft or hard or that it’s painful . . .’

We look on with stunned silence. How does one understand this act of UG? Who is speaking? How does he know? Isn’t that an interpretation, too?

Coffee is served in shining steel tumblers. I am a tea man, nevertheless I try to enjoy the hot coffee, wondering how on earth the host could serve coffee and snacks to so many visitors every evening. The next day I learnt that some guest or other would buy packets of milk and snacks and unobtrusively leave them in the kitchen.

More questions. More scandalous and subversive answers, which are actually no answers at all—all questions are just shot down. He is like a machine gun that goes off every time we toss a question at him. UG himself admits: ‘The machine gun is not interested in killing. But it is designed to trigger and shoot at the slightest movement anywhere, and this machine gun just shoots.’

In these meetings there are always foreigners who usually look a little pinched and lost, and there are always sannyasis or swamijis who all look like thrisankus caught between heaven and earth, and then, determined by some law of life as it were, there is always a joker, a court jester. So then, promptly, the stout and dark man with chubby cheeks and beady eyes comes alive. ‘All right, UG,’ he shouts from the back row, ‘every human being has some weakness, even the great ones. We should understand that. All right, what are we doing here? What are you trying to say? Why are you shooting down everything we say? We can always improve, can’t we? We can change, no?’

There is no such thing as improvement or change or psychological transformation in UG’s dictionary. There is only calamity, death which could be a rebirth, a new beginning. But you cannot desire it, cannot even talk about it, for when it happens, ‘you’ are not there.

The Jewish woman burbles something about ‘enlightenment’.

UG grins as if something absurd had been said. There is no such thing as enlightenment. He is no messiah. He says: ‘Messiahs have only created a mess in the world.’

‘Sir, you should come down to our level and speak, otherwise we cannot understand you!’ a middle-aged man pleads.

‘Sir, I am next to you. Don’t you see?’

UG’s answers are no answers and yet they seem to be perfect answers that sometimes hit you like thunderbolts. Once, a good friend of the host, K. Chandrasekhar, who was a deeply religious man and something of a scholar, had asked UG: ‘Sir, what is the state you are in?’

‘Sir,’ UG had replied, ‘all I know is that I am in Karnataka State. I suppose this is Karnataka State?’

The apparently simple, witty answer stumped him completely, and it was, in fact, a moment of great illumination. He went back home and threw away all the religious books he had treasured as priceless gems till then.

Robert Carr, who has written God Men, Con Men on UG and his own spiritual search, knew J. Krishnamurti before he met UG. His meeting with UG was so disturbing and illuminating that he quit his spiritual vocation and started a restaurant in California. Then there is the story of a psychiatrist who quit his practice and never went back to UG. We cannot also forget to mention the man in Switzerland who, after meeting UG, landed up in a mental asylum. There are literally hundreds of such stories of people who have been tremendously affected by UG in one way or another. Some UG admirers I have met in Bangalore have described UG’s influence on them in ‘negative’ terms: ‘He has not given me anything, rather he has only taken away my ideals, my spiritual search, my fond hopes, illusions, crutches . . . he has helped me simplify my life, to put my thinking on a different track that is free of the burden of the tradition, of all these searches for non-existent goals...’ Of course there are also people who believe that he is an ‘enlightened’ person, a ‘jivanmukta’, whose very presence and touch can change their lives. But ask UG and he would say: ‘You come here and throw all these things at me. I am not actually giving you any answers. I am only trying to focus or spotlight the whole thing and say, “This is the way you look at these things; but look at them this [other] way. Then you will be able to find out the solutions for yourself without anyone’s help.” That is all. My interest is to point out to you that you can walk, and please throw away all those crutches. If you are really handicapped, I wouldn’t advise you to do any such thing. But you are made to feel by other people that you are handicapped so that they could sell you those crutches. Throw them away and you can walk. That’s all that I can say. “If I fall . . .”—that is your fear. Put the crutches away, and you are not going to fall.’

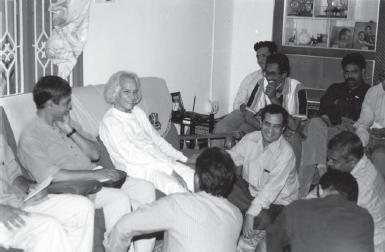

UG in conversation with the author and other admirers

Comparisons can be misleading, for each individual is unique and different. Yet if one were to risk some comparison, if only to enhance our understanding, one might say that UG at times brings to mind the stories of the Zen masters who give sometimes nasty, sometimes provocative, and at times apparently outrageous answers. UG also might impress one like an arrogant and sneering avadhuta3, or a totally indifferent pratyekabuddha, or as one simply, furiously mad!

A Zen koan goes like this: Once, a monk approached a Zen master and requested to be enlightened. The master asked the monk to get closer and then whispered in his ear: ‘Zen is something that cannot be conveyed by word of mouth.’

Once, a disciple, troubled and confused by the many definitions of Buddhahood, asked his master: ‘What is the Buddha?’

The master said, ‘He is no other than this corporeal body of ours.’4

Now, if one did not read between the lines, this answer could only add to one’s confusion, for the Buddha is not generally associated with corporeality. The answer is meant to break the dialectical and dualistic thinking of the disciple and open his eye to the truth.

That is why, when questions about Zen, Enlightenment, or the Buddha-nature are asked, the masters refer to a piece of garbage, to a cat climbing a tree, to the sound of one hand clapping, to waters that do not flow, to the sound not heard by the ear; or the master might just slap or kick the disciple and chase him out.

Attachment, or clinging to knowledge and experience, however profound or insightful, too becomes an obstacle in the realization of Zen or Buddhahood. Hence, seekers are warned: ‘If you meet the Buddha on the way, kill him!’

UG’s answers too, which are apparently irrational, unreasonable, nasty, and at times even abusive, are aimed at shocking and breaking the questioner, lighting a fuse, opening the inner eye, or just stopping one from going back to him again.

Still, people flock around him. They get hurt, snubbed, insulted; they get mad, angry, hopeless, and yet, they go back like moths that want to be annihilated or incinerated in the fire. And then there are the ‘regulars’, like the diehard fans of famous filmstars, who show up every time UG is in Bangalore.

One day, UG said to one of them: ‘Why do you come here every day? You must really be a low-grade moron to come and sit here and listen to the same crap day in and day out. I say the same words, the same things over and over again, there is nothing different. You’ll not get anything from here. There is nothing to give, nothing to take, nothing to know . . . Sorry, you can go to any guru you like. I am not selling anything here. Bye-bye.’

Suddenly, now, someone asks a question that is totally out of tune. ‘UG, what is your favourite dish?’

Grinning wickedly, UG says, ‘Soup prepared out of the tongues of new-born babies.’

Too repugnant to ‘decent’ ears. They could now get up and walk out. But nobody moves. There is an awkward silence. Many of them know that UG does not touch meat, and strictly speaking, he is not even a vegetarian, for he hardly eats vegetables or fruit. While in India, he literally lives on oats with cream, idlis or beaten rice with milk, and an occasional coffee with cream. His total intake of food is less than that of a normal five-year-old. Yet he remains alert and agile throughout the day, exuding tremendous energy. Food is at the bottom of his needs, he says. He sleeps for hardly four hours and is usually up by four or five in the morning, and by six he is ready to take on the visitors who start streaming in from the early hours up to almost nine at night. He can talk for almost twelve to fifteen hours at a stretch and still be as sprightly and absorbed as a child who has not finished with his or her games. He never takes any exercise and yet he is very fit and nimble on his feet, like a cat. He is a marvellous machine. An amazing, miraculous body!

He is no saviour, no god-man; he claims nothing. He defies classifications. He argues that what he says carries no philosophical undertones, no mystical overtones; it is neither enigmatic nor mystifying. His words mean what they say, plainly and simply, as spelt out in any good dictionary. There is nothing profound or spiritual in his utterances, only plain facts and clear descriptions of the simple physiological processes of the body.

But he disagrees with and questions all our assumptions and presumptions, all our ideas and theories, all our pet beliefs and radical notions. He raises his hand in a questioning mudra and deals a deathblow to the very foundations of human culture.

He explodes and declares:

Love is war. Love and hate spring from the same source. Cause and effect is the shibboleth of confused minds. There is no Communism in Russia, no freedom in America, no spirituality in India. Service to mankind is utter selfishness. Jesus was another misguided Jew. Buddha was a crackpot. Man is memory. Charity is vulgar. Thought is bourgeois. Mutual terror, not love will save mankind. Attending Church and going to a bar for a drink are identical. There is nothing inside you but fear. God, Soul, love, happiness, the unconscious, reincarnation and death are non-existent figments of our rich imagination. Freud is the fraud of the twentieth century, while J. Krishnamurti is its greatest phoney . . .

On our way back home, the German friend gushes, ‘What UG says is correct.’ He has obviously enjoyed UG’s attack on the famous personalities, in particular on the Nobel Prize winners. He is young, he has come from Bonn to visit an orphanage and school run by a German woman now separated from her Indian husband. He is a student of psychology. UG has touched a chord in him; he is truly excited.

Back at the doctor’s residence, the doctor asks me, ‘So, what do you think, meeting UG after so many years?’

The German friend’s eyes open wide and he is all ears.

My first thought is that I must write a book on UG, if only for my own clarification. But I only smile like one who has just come back after meeting a long-lost friend!