{2}

‘No Boundaries’

Quite unexpectedly UG was back in Bangalore in September 2002. Three months earlier our daughter Shruti had died in a road accident. It was past midnight when we received the news over the phone. When my wife and I went to the government hospital, at around 2.30 a.m., there was no doctor to tell us how she died. In the mortuary, she lay on a metal stretcher, her hair spread over and trailing down the metal frame; it looked as if she had lain down to relax and dry her hair after a bath. But it was a mortuary, smelling of death and decay.

The boy who had ridden the bike died on the spot but she was still breathing, her friends said. Yet they had only stood there on the blood-splattered road, feeling paralysed, or was it that they were drunk and scared of the police? The ‘golden hour’ was lost. When the police finally arrived, they did not take her to the private hospital which was hardly a five-minute drive from the spot. It was as if nature, her friends and the police had all conspired not to let Shruti survive.

Words fail to describe the sorrow. They say losing one’s child is the greatest sorrow in life. Really, if there is sorrow, this is it. Every other pain or suffering seems trivial compared to this. Two things happen. One, you feel a deep wound in your chest, a gaping hole which never seems to close. Two, you fall into a daze. It lasts for days, perhaps several months for many, but when you come out of it you find yourself in deep pain, struggling to come to terms with the fact of death. If not for that ‘daze’, maybe one would come to reckon with the fact of death and that would be the end of it, emotionally. It usually doesn’t happen, the sorrow lives on.

One astrologer friend said that Shruti had died after twelve in the night, which is the brahma kala, meaning that she had completed her span of life on Earth. Another friend said that we should look at her death differently. She had lived the way she wanted, she had lived a full and vibrant life, something most women and even many men would take a lifetime to experience, while many never would. In effect, they were saying it is not how long but how you live that is important.

But words don’t console you and you realize they have no meaning, they are empty like the hollow of your hand.

Three days after the funeral I went to the burial ground. It was as if I was seeing the world from afar, very far, yet I could see everything in its minutest detail. There were so many men, women, boys, girls and children everywhere, even cats and dogs and buffaloes and cows, and occasional birds crossing the dismal sky or perched on tree tops or on electric poles; inside the burial ground, a scrawny goat stood stubbornly on a tombstone. And I felt with a stab in my heart that my daughter was nowhere there. The same evening, in the third column of the edit page of a popular newspaper, I chanced upon a familiar quote from Shakespeare’s King Lear. Upon being told of the death of his most loved daughter Cordelia, King Lear wails inconsolably thus:

Why should a dog, a horse, a rat have life,

And thou no breath at all? Thou’lt come

no more,

Never, never, never, never, never . . .

The next day, when I went out I again confronted the same reality, but there was a strange, and different perception of things this time. ‘Look,’ I told myself, ‘there is life everywhere, it is the same life, it is Shruti everywhere, the same life-energy pulsating in every creature, everything . . .’

Streams of friends come and go, many sit in silence, and when they finally manage to speak, they only say that they don’t know what to say. Yes, what can they say? They know that one can never console the parents, it’s better to remain silent. But life goes on. Habits take over. There is hardly any break in the routine. Hunger for food never ceases. The tongue never fails to recognize the taste of food, or distinguish between tastes. Life both sustains and survives death. UG is right, I think. The body is indifferent; it is not in the least concerned about your sorrows, it is only interested in its own survival. Joys and sorrows are only a nuisance, an avoidable disturbance in the chemistry of the body, to its otherwise harmonious function. Fortunately, the endocrine glands which control and regulate the vital functions of the body are not affected. The body does not care about death, it goes on.

Before my daughter’s death I had started working on this book. I had already referred to a dozen books and made copious notes. I started working again and attending to my duties at the college.

I went to meet UG on the very day of his arrival in Bangalore. The long ride, almost twenty-five kilometres, on my scooter in the hot afternoon, tired me. I was sweating and feeling a little odd about my worn-out demeanour. There were already about twenty people in the room. Most of them looked familiar. Heat or rain they would be there, if only to be in the explosive presence of UG.

UG returned my greeting and said, ‘Come, sir.’ And I was directed to sit beside UG on the sofa.

‘How are you, sir? You look old!’ said UG with a smile.

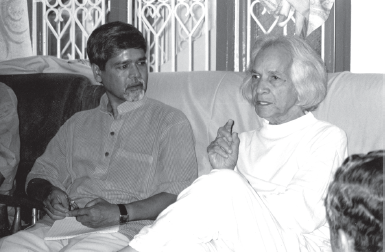

The author with UG

‘Old and wise!’ he quipped, flashing a smile.

‘I’m flattered, sir,’ I said. ‘You didn’t recognize me the last time.’

‘I was prepared, sir,’ he said, deflating the sense of pride or whatever I had begun to feel.

Just then the lady of the house came out and passed around two plates of sweets. UG offered his plate to me and said, ‘Take, sir. You are not sweet enough!’

I did not react. I took a small piece of the milk sweet and looked around, now feeling a little awkward. Chandrasekhar Babu, the host, who was sitting at the other end, mentioned my daughter’s sudden death to UG.

Over the years I have seen that people react to news of death in different ways. There are those who find it difficult to speak and then fall silent, those that deliberately start speaking about other things, those that have ready-made words of condolence and then come out with stories of death as if that would somehow console us, and those who think that they are expected to speak about their own experience of death and suddenly become melancholically loquacious.

I have not heard UG speak about (actual) death. UG would, of course, respond to the news of death as he would respond to any other subject, without any show of emotion or sympathy. But more than ten years ago, I was told, UG had made an unexpected remark about the sudden death of one Nagaraj who was the private secretary to the Postmaster General of Karnataka. He never married. ‘The cigarette is my beloved,’ he used to say. Whenever UG came to Bangalore, Nagaraj would apply for two or three months leave from his office and spend the whole time with UG. ‘UG, consider me as part of the furniture here. I have nothing to ask of you. Please let me just hang around here. That’s all I want,’ he would say. He made notes in shorthand of UG’s conversations with the visitors, which were later used in the book Mind is a Myth.

Nagaraj retired from his job but not from his smoking habit. When he couldn’t control the urge, he would go out, puff away hurriedly at a cigarette and then come back to his spot close to UG. One day, he suddenly decided to quit smoking. When he mentioned it to UG, expecting some encouragement, the latter said, ‘Double your quota. Don’t stop smoking,’ and even assured him that he wouldn’t die of lung cancer. But Nagaraj stopped smoking, fell into depression, ignored the withdrawal symptoms and died a year later. Recording the incident in her book, Shanta Kelker writes: ‘. . . I kept repeating, “UG, I just can’t believe Nagaraj is no more. I half expect him to walk in any minute with his loud hellos.” UG replied, “What makes you think he is not there? He is very much here now.” That jolted me. I turned around to see if I could discern any friendly spectre gracing the scene, but to no avail. Trust UG to see things which the rest of us can’t! UG continued, “Even when you thought you were seeing him when he was alive, you were not actually seeing him. Do you think you can see anything or anybody?”’5

On another occasion, upon hearing about the death of a young man called Papanna who used to come and see UG every time he was in Bangalore, UG had suggested to Chandrasekhar Babu that they should go to see the boy’s mother. As soon as she saw UG at the door, she rushed out of the kitchen to receive him. She was about sixty; it was a family of great musicians. Her eyes filled with tears and she soon started talking about her son. UG listened to her tale of woe in utter silence. Only Chandrasekhar interrupted her a couple of times and offered some words of consolation. UG did not, he just listened to her with total attention. After nearly half an hour, when she was exhausted and somewhat calmed down, UG got up, did his pranams to the mother and walked out. The mother probably believed UG to be an enlightened man and expected him to say some consoling words. But UG offered none, nor cared to please the family by accepting their food and drink. However, he had let the mother pour her heart out, let her empty herself of the dead weight.

In 1982, UG’s son Vasant died of cancer at the age of thirty-two. Friends and close associates say that during those days they did not see even a trace of sadness in his face. UG was in Bangalore when he received a telegram which stated that Vasant had cancer and had been admitted to Bombay Hospital. His reaction to the news, Bangalore friends say, was not remotely close to that of a father. However, the friends in Bangalore insisted that UG should spend the rest of his time in India with his son in Bombay. Mahesh Bhatt received UG and his companion, Valentine, and made arrangements for their stay in Bombay. It so happened that Valentine fell ill suddenly; she had contracted tuberculosis and she had to be hospitalized. Mahesh Bhatt says that UG and he had to shuffle between the two hospitals at the opposite ends of the city. Friends who believed UG had miraculous powers expected him to cure his son of the cancer. UG laughed the idea off, saying that his touch would only hasten Vasant’s death rather than cure him of cancer.

‘Why should this happen to the son of someone like you?’ asked a friend of UG, meaning how could an ‘enlightened’ man’s son die of cancer.

UG asked, ‘Why not my son?’

It seemed a callous, heartless response coming from a father. And yet, every day, UG went to the hospital and sat by the bed of his dying son. And he was there when the end came.

Mahesh Bhatt writes: ‘ “He is dead,” said UG, in a matter-of-fact tone over the telephone. He asked me to meet him at the hospital to make arrangements for the funeral. We had known that Vasant’s end was near. One of my friends had hoped that UG would perform a miracle. As we walked to the hospital after hearing the news of Vasant’s death, my friend believed even then that UG would bring his son back to life. What actually happened at the hospital took us totally by surprise. UG wanted the body to be removed and cremated immediately without any ceremonies. The hospital would not release the body until all the bills were paid. It was 6 a.m. and our total combined resources were nowhere near the amount needed. Then UG laughed and said, “You can forget about your sentiments and solemnity surrounding death. In the end it all comes down to money.” We were shocked. We all found his conduct quite lacking in the decorum that such an occasion demanded. The expected miracle did not occur. We were amazed at UG. There was no trace of emotion in him. He simply attended to the legal formalities that were necessary for the cremation and walked away from the scene.’6

While my daughter, Shruti, still lay all wrapped up in white sheets, but adorned with flowers and a huge garland of roses, the first copy of my new book Rama Revisited and Other Stories arrived by post. In a story called ‘Sanjaya Speaks’, which is based on the aftermath of the Kurukshetra war, Sanjaya, thinking of the suffering of Kunti and Draupadi, speaks to himself thus: ‘Suffering is a disease, mother. It eats into your vitals and destroys your sanity.’

Later in the story, on seeing her children’s bodies cut to pieces by Ashwathama’s sword, Draupadi turns hysterical and revengeful. But the ghastly sight snaps something inside Yuddhisthira; he decides to renounce everything and go off to live the life of a hermit. He rejects everything, the bloodstained victory, his wife and brothers, even Krishna whom he calls an unrealized god, an unborn truth. He declares: ‘I reject you all . . . I shall leave you all, strip myself of this yet fatal garb of civilization, and wander through the forest and live the life of a hermit. I shall meet cold and heat and illness and hunger and death as they come. I shall live on fruits fallen from trees, never pluck them from trees nor from the ground. I shall totally abjure violence and fear no creature. If a tiger chews off one of my arms, I shall offer him the other arm, nay, my whole body if that should satiate his hunger. I will go on thus, forward and never back, but with no goal in mind, for all goals are delusive . . .’7

I agree with Sanjaya; suffering is really a bad habit. I understand Yuddhishthira and feel like him, but I cannot do anything about it any more than Yuddhishthira himself did in his life. And I think I know why UG was unaffected by his son’s death and behaved the way he did. But I suffer like every other father who has lost his child. I tell myself: we live and it’s a blessing. Human life is a blessing! Or is it a curse? Shruti never walked, she always ran. Even a hundred years would have been insufficient for her energetic soul, I tell my friends. She never got a chance. Some of us have been blessed with a chance or two; I had a miraculous escape once in a road accident; but this girl, this most marvellous piece of work, this spirited life that deserved to live, never got another chance. And I tell my wife: ‘She is not the type who’ll remain out there for long. She’ll return. She’ll live again, but not as our daughter.’

But is there life after death? Is there reincarnation? Or is it just a belief sprung from our fear of death, our fear of nothingness; from the sense of void the dead leave behind? On a number of occasions, UG has said that there is no rebirth, but if you believe in it, there is—indeed a very intriguing and paradoxical answer.

I recall here a moving story from J. Krishnamurti’s Commentaries on Living. It is one of the most insightful and profound dialogues on death one could ever read. In these commentaries, Krishnaji usually starts with a long description of the place, environment and people, before moving on to the dialogue. In this particular section, he starts off with descriptions of a magnificent old tamarind tree, of pilgrims who come from all parts of the country to bathe in the sacred waters, of the moon making a silvery path on the dancing waters, and then offers a brief sketch of a funeral as a prelude to the discussion on death. The precise, simple prose is a marvellous piece of writing that combines most effectively the technique of the essay with story telling. ‘... Often they would bring a dead body to the edge of the river. Sweeping the ground close to the water, they would first put down heavy logs as a foundation for the pyre, and then build it up with lighter wood; and on the top they would place the body, covered with a new white cloth. The nearest relative would then put a burning torch to the pyre, and huge flames would leap up in the darkness, lighting the water and the silent faces of the mourners and friends who sat around the fire. The tree would gather some of the light, and give its peace to the dancing flames. It took several hours for the body to be consumed, but they would all sit around till there was nothing left except bright embers and little tongues of flame. In the midst of this enormous silence, a baby would suddenly begin to cry, and a new day would have begun.’

The narrative then moves over to the dying man. He is a fairly well-known person. He lies on a cot, surrounded by his wife, children and close relatives. As Krishnaji walks into the room, the old man waves him to a chair and asks his people to leave them alone for awhile. The dying man speaks with difficulty: ‘You know, I have thought a great deal for a number of years about living, and even more about dying, for I have had a protracted illness. Death seems such a strange thing. I have read various books dealing with this problem, but they were all rather superficial.’

‘Aren’t all conclusions superficial?’ Krishnaji simply asks.

‘I am not sure,’ the old man begs to differ. ‘If one could arrive at certain conclusions that were deeply satisfying, they would have some significance. What’s wrong with arriving at conclusions, so long as they are satisfying?’

With remarkable tact Krishnaji agrees only to point out that the mind has the power to create every form of illusion, and to be caught in it seems so unnecessary and immature.

But the old man persists: ‘I have lived a fairly rich life, and have followed what I thought to be my duty; but of course I am human. Anyway, that life is all over now, and here I am, a useless thing; but fortunately my mind has not been affected. I have read much, and I am still as eager as ever to know what happens after death. Do I continue, or is there nothing left when the body dies?’

‘Sir,’ Krishnaji asks tenderly, ‘if one may ask, why are you so concerned to know what happens after death?’

‘Doesn’t everyone want to know?’

Krishnaji refuses to answer, for there are no answers. But he asks . . . ‘If we don’t know what living is, can we ever know what death is?’ And he goes on to suggest most persuasively that living and dying may be the same thing, and the fact that we have separated them may be the source of great sorrow. Why doesn’t one allow the whole ocean of life and death to be? At last the man admits: ‘I don’t want to die. I have always been afraid of death . . . All my reading about death has been an effort to escape from this fear, to find a way out of it, and it is for the same reason that I am begging to know now . . . You can tell me, and what you say will be true. This truth will liberate me . . .’

‘But what is this “me”?’ Krishnaji asks. ‘The ‘me’ exists only through identification with property, with a name, with the family, with failures and successes, with all the things you have been and want to be. You are that which you have identified yourself; you are made up of all that, and without it, you are not.’

But the dying man wouldn’t give up, he wouldn’t let the ocean of life and death be. He wants to know, he grows desperate. He feels he has become the hunter as well as the hunted. He begs Krishnaji to be compassionate, not to be so unyielding. His mind is now like a galloping horse without a rider. He begs Krishnaji for some clue, some solace. He cries and asks, ‘Will you help me, or am I beyond all help?’

There is no help. The very need for help is the problem, which prevents one from letting all things go and be. ‘Truth is a strange thing,’ Krishnaji says and he is magnificent, and his concluding remarks wash over the dying man like the cleansing waters of the Ganges. ‘You cannot capture it by any means, however subtle and cunning; you cannot hold it in the net of your thought. Do realize this and let everything go. On the journey of life and death, you must walk alone; on this journey there can be no taking of comfort in knowledge, in experience, in memories. The mind must be purged of all the things it has gathered in its urge to be secure; its gods and virtues must be given back to the society that bred them. There must be complete, uncontaminated aloneness.’8

Now, turning to me, not smiling any more, in a rather sombre voice, UG, this other Krishnamurti, only asks, ‘How old was she?’

Is it an opening offered to me to speak about my daughter, about death? Is it an invitation to ask questions that had been troubling me all these months? I just say, ‘She was twenty-one,’ and stop there. But actually I want to tell him that Shruti was a rebel, that she was a great critic of all our much-talked-about social values and beliefs, that she thought her mother’s social activism and feminism, her father’s philosophy and writings were all so much sham, or that we were not too different from the ‘stupid’ conservatives or traditionalists we often like to criticize. She would have been an apt disciple of UG. Three years before her death, when she had just turned eighteen, she had written in her diary that being a prince the Buddha had everything at his disposal, probably more than what he desired, and so could afford to say that desires and worldly pleasures are the beginning of sorrow. If he had been born in a poor family, he would have probably wanted to be a prince, or sought all kinds of comforts and luxuries. If the Buddha, who declared ‘Desire is the cause of all suffering’, was alive today, he would get no followers. For today’s life is all about desires. ‘I have desires,’ she declares. And she goes on to say that she wants to fulfil all her desires. Be a contented human being. And then, she concludes: ‘. . . of course die when the time comes.’

I want to tell UG that eight months ago, when I had taken a couple of friends to see him, Shruti had complained to her mother that I had not cared to invite her. She would have surely enjoyed, like the German friend, UG’s irreverent remarks, his demolition acts, his total dismissal of all authority, in particular the religious. She detested authority, parental authority in particular. She was a free spirit, a wild bird that loved to fly aimlessly in the untrammelled air. Shruti lived intensely, almost feverishly as if there was no tomorrow. I imagine her riding pillion on the 800cc sport bike, her hair flying in the cool midnight breeze, screaming in joy, before the lorry pulled out on to the middle of the road and stopped her and her friend in their tracks.

In one of her college assignments, ‘Clocks’, beside clocks of different designs embedded in strange settings, Shruti had written:

Time is merciless

Yet heals,

Brutal

Yet binding,

Irreversible

Yet changing.

Time is a bitch . . .

It is like fate

Lines on your palms,

All decided

Much before you arrive . . .

Elsewhere, next to a picture of a girl with large wings, she had scribbled:

Free spirited

No boundaries

No limits

No questions.

After the milk sweets, there is some khara, salty and crispy munchies to kill the sweet taste so that the coffee will not go bland on the tongue. Soon, the discussion picks up. Actually it is no discussion. It is a monologue—or, rather, only talking. It seems pointless to ask who is talking to whom. There is only talking, either loudly and outwardly, or silently and inwardly, and both are a single unitary movement. Hilarious, scandalous, ironical, sardonic and paradoxical. At one point during this freewheeling blather and what seemed uproarious yet obscene and repulsive laughter, the subject of death pops up. UG declares: ‘There is no way you can experience death, least of all your own. You only experience void. And the void is nothing but a break in the continuity of memory, of knowledge. Relationship is nothing but memory, knowledge. So, what is death without memory?’

A crack in the delusion, a chink of insight, a seed sown, and I realized I could not pull it up, push it open, there was no magical, mystical way for him. An involuntary sigh escaped me. It was time to leave. The sun had gone sneakily, the heat was down, and one could feel a cool breeze playing in the trees outside. I got up and made my pranams. UG looked up and brought his palms together and smiled briefly, fleetingly, a little enigmatically, I imagined.

I really do not know how I can possibly capture or interpret that smile in my story. It has surely to be a ‘memorable’ task! Is there really anything beyond memory?

Shruti’s life was like UG’s smile, brief but warm, very warm, and enigmatic, too!