AND SO AT ONE O’CLOCK in the morning I found myself with Morley and the headmaster in the long corridor outside the boys’ dormitories. All was quiet as we shook warm grey ashes onto the cold red lino floor. The idea was that we might be able to identify whichever boy then crept out of bed to go and attack Mr Gooding’s animals – an utterly ludicrous plan, in my opinion, though Morley and the headmaster were convinced that their trap would work, and that the mystery would be solved, that we would discover who was harming the animals, and so order would be restored to All Souls. To me the entire enterprise seemed a distraction from the rather more serious matter of poor dead Michael Taylor. I did not believe for one moment that any boy would be foolish enough to emerge from the dormitory that night. I said as much to Morley, quietly, when the headmaster absented himself for a moment, in order to fetch some blankets and a sustaining flask of tea.

‘There is something very wrong in this school, Mr Morley.’

‘Very wrong?’ said Morley.

‘Yes.’

‘Can something be “very” wrong, Sefton? Surely if something is—’

‘I just mean that something is wrong,’ I said. ‘Wrong wrong. As in not right.’

‘Well, I quite agree, Sefton. And if we find out whichever boy it is who’s causing harm to the animals then I think we’ll have solved the problem, don’t you? Cessante causa, cessat effectus and what have you.’

‘I’m not sure that is the answer to all the problems here, Mr Morley.’

‘Oh. Well, what do you think is the answer?’

‘I don’t know, sir. But I do know schools, and I know that this place is not the same as other schools that I’ve—’

‘One would hope not,’ said Morley. ‘The headmaster is trying to do something different here, Sefton. In these beautiful new surroundings. I’ve been sharing with him some of my ideas about education, actually, and I think he might be interested in adopting some of the principles for the school – providing the boys with a truly all-round education that will see them fit not only for the professions but for life. It would transform the place, don’t you think?’

‘I’m sure it would, Mr Morley, but I’m not convinced it would solve the fundamental problems here.’

‘Which are?’

‘I’m not certain, but … Don’t you think the set-up here is a bit … odd?’

‘The “set-up”, Sefton?’

‘Well, the headmaster and his brother and their mother and … They all seem very …’

‘What?’

‘I don’t know. It’s just that … I don’t know.’

‘Well, perhaps when you do know, Sefton, and you’ve worked it all out, perhaps you could let me know? In the meantime, in the absence of any ideas or plans of your own, could you perhaps help me and the headmaster lay our modest trap?’ The headmaster had by this time returned with the supplies – the blankets, a flask of tea. Morley grabbed a handful of ashes. ‘Come on, man, for goodness sake. Dare to be a Daniel, eh? Come on, shake!’

So we all shook the ashes and then we drew up chairs to wait. There were two stairways up to the dormitories, and two dormitories, one for the older boys, one for the younger. I was stationed at one end of the corridor. Morley and the headmaster were stationed at the other. A few candles in sconces lit the corridor and the pale ashes lay between us.

We agreed to take two-hour watches. Morley and the headmaster took the first watch at their end of the corridor. I dozed uneasily on the chair, wrapped in the blanket for warmth.

Half asleep and half awake, I found myself plunged once again into memories of the horrors of Spain at night. Not the gunfire, not the ambushes, but worse: memories of the fellow volunteers who would stub out a cigarette on your neck while you were sleeping; and of the men who would steal from you, your cigarettes, your boots, your food; or who would piss on you to wake you. One night I recall I had asked a Frenchman, Gérard – a huge man, famous among all the Brigaders and known as La Bestia, who liked to boast of the battles he had survived, and the men he had killed, and the women he had slept with – who was drinking and playing cards with friends, to quieten down so that I could sleep. They ignored me and somehow through the noise I managed to fall asleep, only to awake to find La Bestia with his hands around my throat, trying to choke me. Fortunately he was so incapable with drink that I easily managed to throw him off, and afterwards we became firm friends, but it was disconcerting, the realisation that one was as much at risk from one’s own side as from the other.

And then I wakened with a start when Morley shook me at 3 a.m. It was my turn to go on watch.

I managed to keep my eyes open for I know not how long and when I came to again it was to the sound of footsteps. I opened my eyes. The corridor was empty. The few candles in their sconces were guttering out. A weak moonlight shone through from the single window at the end of the corridor, barely illuminating the dark footprints in the ash. The footprints weren’t coming from the dormitory. They were heading towards the dormitory: the younger boys’ dormitory.

I silently unwrapped myself from my blanket and quietly tiptoed my way down the tallow-tinted corridor to the dormitory door, stationing myself just outside so that I could grab whoever it was as they exited. All I could hear was the sound of breathing – the boys, asleep – and my own heart beating. From outside there came the sound of an owl hooting.

And then there came the sound of shuffling towards the door.

I braced myself and as the dark figure emerged from the doorway I swung a ferocious punch towards their head, which knocked them sideways and banged them loudly against the door jamb. As they slumped down towards the floor – and before I had properly prepared myself for an assault – another figure came rushing out after them. As they blundered into me I grabbed at them. They gave a yelp and I held tight and dragged them into the dim light of the corridor.

‘What on earth?’ said the headmaster, who had come rushing down the corridor at the sound of the commotion. ‘What on earth is the meaning of this?’

‘Headmaster,’ said the man I had apprehended.

‘Jones?’ said the headmaster. It was one of the teachers – Jon Jones the Welshman.

The figure on the floor was groaning.

‘What are you doing here?’ asked Morley, who had also joined us.

‘I might ask you the same,’ said Jones, in his challenging Welsh fashion.

‘We are here, Jones, to try to get to the bottom of these problems with the animals,’ said the headmaster.

‘Same as us then,’ said Jon Jones.

‘Really?’ I said.

‘Really,’ said Jones, staring at me.

‘Come on, get this man up,’ said Morley, reaching down towards the man on the floor.

‘Mr Dodds!’ said the headmaster. ‘I am so sorry.’

Mr Dodds, the benefactor, gradually rose to his feet, with Morley’s assistance. In one hand he was clutching a teddy bear.

‘Ah, a Steiff,’ said Morley, admiring the bear. ‘Very nice. Very nice indeed. Never mind your Siemens: German engineering at its best, a Steiff.’ Mr Dodds offered Morley the bear to examine. ‘Thank you. But why might you be stealing teddy bears from the boys’ dormitories?’

‘We thought,’ said Jones, ‘that if we took a few teddies it might teach the little—’

‘Children,’ said Morley.

‘A thing or two,’ continued Jones.

‘Really?’ said the headmaster. ‘And teach them what exactly?’

‘An eye for an eye, presumably,’ said Morley.

‘Exactly,’ said Jones.

‘The old lex talionis.’

‘It’s just a bit of fun,’ said Mr Dodds. ‘Jones and I were going to set up a few of these little creatures as target practice.’

‘What?’ said the headmaster.

‘Just a bit of fun, Headmaster,’ said Mr Dodds, who had clearly been drinking heavily.

‘Just a bit of fun?’ said the headmaster. ‘Creeping into the boys’ dormitories in the middle of the night to kidnap their soft toys?’

‘Surely you can see the funny side, can’t you?’ said Jon Jones.

The headmaster looked stern. Mr Dodds barked with laughter.

At the sound of the laughter a group of boys – all of them in their regulation blue and white striped winceyette pyjamas – timidly made their way out into the corridor and gathered around us. They looked terrified.

‘Nothing to see here, boys,’ said the headmaster. ‘Back to bed, please. Immediately.’

‘Headmaster,’ said one small boy. ‘I need to pee, sir.’

‘Use the chamberpot, boy.’

‘Chamberpot’s full, sir.’

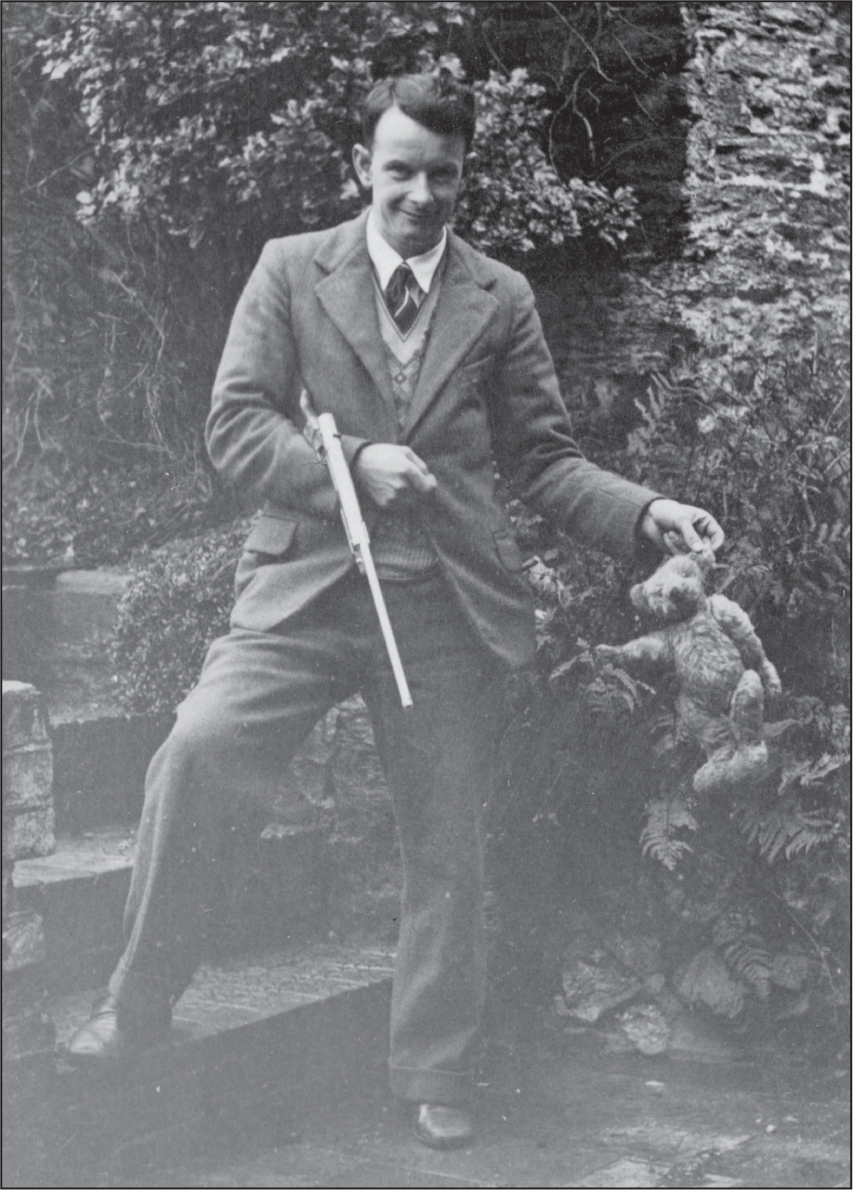

Mr Jon Jones, in challenging Welsh fashion

‘You’ll have to wait until the morning, I’m afraid.’

‘Headmaster,’ said another boy. ‘There’s something on the floor, sir. A sort of white powder, sir.’

‘Never mind,’ said the headmaster.

‘What is it, sir?’

‘Ashes: someone has spilled some ashes.’

‘Headmaster,’ said another boy. ‘Michael Taylor’s not here, sir.’

‘No. I know. Michael has … gone away.’

‘Where is Michael Taylor?’ asked Jon Jones. ‘I didn’t know he was away.’

‘Is he ill, sir?’

The headmaster ignored the question.

‘It’s time for bed, gentlemen,’ said the headmaster. ‘I will deal with you in the morning, Jones. In the meantime, perhaps you’d be so kind as to escort Mr Dodds to one of the guest rooms. Everything’s fine,’ he reassured the boys. ‘Everything in hand and under control.’