I RETURNED EXTREMELY LATE to the school, late enough for it no longer to resemble a school, but almost to have returned to its former status as a grand home. The corridors were profoundly quiet. All that could be heard in the entrance hall was the ticking of the grandfather clock, which only deepened the profundity. I stood for a moment and enjoyed the steady rhythmic silence, imagining the place as it once was and was intended to be: a home for the wealthy and privileged rather than a home for the sons of the wealthy and privileged, a home with a father, and a mother, a place ruled by adults who were parents and not merely in loco parentis; a place with a heart.

I considered going straight up to the farm and to bed, but then I thought perhaps I should find Morley. I was rather keen to use my new-found knowledge of Alex to my advantage. If he had been blackmailing Mrs Dodds it seemed highly likely that he might have tried the technique with others. I had no intention of course of divulging the information Mrs Dodds had shared with me, but I wondered if I might at least be able to put a dent in Morley’s uncritical admiration for the man.

I went to the school library. But Morley was not there. I went to the kitchen. And Morley was not there. I went to the staff common room. And he was not there. I thought perhaps he’d retired for the evening to his room, perhaps to read: his nightly habit of reading a book before sleep was one that he maintained throughout our time together, which meant that – on a rough calculation, and not including the books he reviewed, weekly, or the books he read for research, daily, or indeed of course the many books he wrote, numbering into the many hundreds – he had read a thousand books, at night, for pleasure, during our acquaintance. I read perhaps a dozen, dozily – and mostly by him.

I was about to give up. But then I heard a strange sound. It was the sound of laughter, and something else – a kind of clucking, or clicking, like something was stuck in the throat. I made my way uncertainly towards the noise.

It was coming from a room I had not entered before. The thick oak door was temptingly ajar, and I peeked in: dim lighting, a fire in the grate, and Morley and the headmaster side by side in their shirtsleeves, cues in hand. They were engrossed in a game of billiards.

‘Ah, Sefton,’ said Morley, spying me immediately.

‘Billiards,’ said the headmaster redundantly.

‘Let us lean across the cloth of green and o’er the rigid cushion lean,’ said Morley. Whether he was quoting something or making up verse on the hoof it was often difficult to tell; either way it was not perhaps his finest rhyme. Also, I hadn’t expected to see him playing billiards.

‘Billiards,’ I said pointlessly, echoing the headmaster.

‘Yes. And I do believe I have perfected my screw,’ said the headmaster.

‘Intent on some strategic stroke,’ said Morley, slapping the headmaster on the back. ‘He raised his cue and so he smote.’

‘And now I shall pot the red,’ announced the headmaster.

He leaned over, pulled back, took his stroke – and the red kissed the cushion and then ricocheted to kiss another red.

‘Blast!’ said the headmaster.

‘I wish I could share your disappointment,’ said Morley. ‘But I must confess I am secretly delighted.’ He began carefully chalking his cue. ‘Now, Sefton, how was your evening? Good film?’

‘Yes. It was …’

‘What did you see?’

‘Dangerous Secrets?’ I said.

‘We have had an interesting evening ourselves, haven’t we, Headmaster?’

‘We have indeed, Morley, we have indeed.’

‘The police have charged a couple of boys with the theft of Mr Gooding’s animals.’

‘Really?’

‘Very unfortunate,’ said the headmaster. ‘But we can’t have that sort of thing going on in school.’

‘Precisely,’ said Morley.

‘Couple of the younger boys. Unexpected. But they both confessed, apparently.’

‘I see,’ I said. ‘And Michael Taylor?’

The headmaster turned pale at the mention of the poor boy’s name.

‘Yes,’ said Morley. ‘The police seem to think that he drove himself over the cliff – an accident.’

‘Rather than a suicide?’ I said.

‘I don’t think that’s even a possibility, is it?’ said Morley.

‘De omnibus dubitandum?’ I said, quoting one of Morley’s favourite Latin phrases.

‘Anyway,’ said Morley. ‘The headmaster has suggested a few more places we need to visit for the book, Sefton. Wistman’s Wood, up on Dartmoor—’

‘Grows straight out of the granite,’ said the headmaster. ‘All oak.’

‘Exclusively oak,’ agreed Morley, blowing excess chalk from the tip of his cue. ‘And at least five hundred years old. A must-see, wouldn’t you say, Sefton?’

‘Possibly something BC,’ added the headmaster.

‘We shall have to investigate, Sefton. A sacred grove of the Druids—’

‘So people say,’ added the headmaster.

‘Who would gather mistletoe from the aged oaks, one assumes. Also, according to folklore, the home of the Black Huntsman, is that right, Headmaster?’

‘Indeed. Allegedly. And his pack of Wish-hounds.’

‘Whose wild cries may be heard at night. Sounds wonderful, doesn’t it, Sefton?’

‘Marvellous,’ I said.

‘We’ll tell you all about the other places after we finish this frame though, shall we?’

‘Don’t let me stop you,’ I said.

They played on, speaking between themselves as old friends do. I slumped in an old overstuffed leather armchair and lit a cigarette. I always had the idea of Morley as an isolated man, yet he was not an isolated man at this moment: he was a man entirely relaxed in another’s company. That moment, that evening, the two old friends before the fire in the billiard room, it seemed to me, was a portrait of pure agape: a subject about which and upon which Morley wrote at length, in perhaps his most unfortunate and most misunderstood little pamphlet, One Love (1939), in which he calls for a brotherhood of mankind based on the principles of agape, taking as his text 1 John 4:18: ‘There is no fear in love; but perfect love casteth out fear, because fear hath torment. He that feareth is not made perfect in love.’ One Love, Morley always insisted, was not a plea for appeasement: the misunderstanding arose, according to Morley, because of people’s failure to understand St Augustine’s concept of ‘ordinate loves’. I’m afraid I rather failed to understand it also. But on that night this was all a long way away.

After they had finished their frame – Morley winning with a final triumphant thwack – they placed their cues back in the racks.

‘Now, a drink perhaps?’ said the headmaster. ‘I think we deserve one, don’t you? I know you won’t of course, Morley, but I wonder if your young friend here might?’ He looked at me hopefully. ‘You might like to see the cellar, in fact?’ suggested the headmaster. ‘Have you seen the cellar? It is wonderful. One of the advantages of the new school here: all this underground storage. Marvellous. We had nothing like it before. Also, we managed to pick up some excellent claret in France a few years ago – ten shillings a dozen, I think it was. Absolute bargain. Would you like me to show you?’

‘Well …’

Morley shrugged on his jacket. ‘Gentlemen, I do not partake, as you know. And I am rather tired. I have an article to write for tomorrow.’

‘Anything interesting?’ asked the headmaster.

‘Something about this Bodley Head book, Ulysses. Have you come across it?’

‘I can’t say I have, Morley, no.’

‘Some Irish chap. Odd, but rather interesting. More Sefton’s sort of thing. Eh, Sefton?’

I smiled weakly. I had in fact procured a smuggled edition of the original Ulysses some years ago – and sold it when I was short of cash, not having read a single page.

‘Too long, too scatological, and too self-consciously strange, in my opinion.’ He glanced at both his watches. ‘But there is something to it … Can’t quite make up my mind. But, Time and Tide wait for no man. So I will bid you goodnight.’ He made towards the door.

I saw my chance.

‘Headmaster,’ I said, ‘I would love to visit the cellar – and perhaps the darkroom I have heard so much about?’

‘The darkroom?’ said the headmaster. ‘That’s rather Alex’s domain.’

‘So I understand, but—’

‘You know I’m rather thinking of getting something going along those lines back at St George’s,’ said Morley, on the verge of departure, but his endless curiosity obviously piqued. ‘Didn’t know you had a darkroom, Headmaster. I might join you gentlemen, if I may?’

‘By all means,’ said the headmaster. ‘I’ve not seen inside it since we moved in. I’d be interested to see what he’s done with the place.’

And so we all made our way downstairs.

‘Actually, I wonder if I might have a word, Mr Morley,’ I said quietly, as the headmaster led the way.

‘A word about what, Sefton?’

‘It’s rather personal, actually.’

‘Oh dear,’ said Morley. ‘Can it wait?’

‘Don’t mind me,’ said the headmaster.

‘These things can usually wait,’ said Morley.

‘Indeed,’ said the headmaster.

‘I’m not sure,’ I said. ‘I—’

‘Now, the keys,’ said the headmaster.

‘Have been speaking to someone about Alex …’

The headmaster had produced a huge bunch of keys from his jacket pocket and began rattling them.

‘Alex set it all up down here. Very keen to get the boys involved in new technology of all kinds. Tremendous amount of expense. He’s also had a few typewriters brought in. Teaching the boys to type! Quite something.’

‘Essential skill,’ said Morley. ‘Should be taught to all schoolchildren along with penmanship.’ (For further – extensive – elaboration on this point see Morley’s Light Touch Typing for Boys and Girls, 1937.)

‘Now, which is which?’ said the headmaster. He tried one key. And then another. And another. Until he had tried them all.

‘You know, I thought I had the key.’

‘Apparently not,’ said Morley.

‘I can go and look for them up in my office. Won’t take long. They must be there somewhere.’

‘I could probably save you the time, Headmaster, if you would like?’ said Morley, feeling in his own jacket pocket.

‘Really? What? Abandon the plan and head straight for the cellar?’ He winked at me. ‘Not a bad plan, eh, Sefton?’

‘With your permission, Headmaster?’ Morley had produced what appeared to be a small pocket knife and brandished it before him.

‘Goodness me,’ said the headmaster. ‘You’re going to … cut the door open?’

‘Jemmy it, I think is the phrase, Headmaster,’ said Morley, unfolding the knife to reveal what appeared to be a long paperclip. ‘But no. Not exactly.’

‘You’re going to … pick the lock?’

‘Possibly,’ said Morley, who quickly proceeded to do exactly that.

‘Extraordinary!’ said the headmaster. ‘Have you been taking lessons, Morley?’

‘Not lessons, no,’ said Morley. ‘But there was an occasion in Tehran where I had to make a hasty exit from a locked room. Misunderstanding about an interpretation of the Qur’an.’

The door swung open into darkness. I have never been scared of the dark, but years later, when we had indeed established Morley’s own darkroom at St George’s, and I was free to come and go and to use it day or night – though it sounds absurd – I chose never to go there during the hours of darkness. It may sound ridiculous to admit it, but the darkness inside a darkroom is of a kind – a total kind, a negative kind – that induces in me a sort of dread. One might almost believe that in a darkroom at night the souls of photographs come out to haunt one. Ridiculous, of course. But true.

The room was no more than ten feet square. It was lit by a red safelight. Everything was red: we looked as though we had bathed in blood. Solid wooden shelving had been installed all the way up to the ceiling. There were buckets set on the floor. Trays. And on one low shelf was a collection of cameras. Morley could not resist them.

‘Well, this is a little treasure-trove,’ he said. ‘Absolutely marvellous! Look at this, Sefton. Little folding Kodak. A Zeiss. A Zeiss! Baby Box.’ He picked up one from the shelf and held it out in his palm. ‘Look at this. A Kodak Vest Pocket, if I am not mistaken. I have always wanted to get my hands on one of these little beauties.’ He held the camera up close to me. ‘Just look at this.’ I looked: it was a small camera. ‘This is the future, Sefton, mark my words. Pocket cameras. In years to come everyone will be equipped with one of these things. We’ll be able to record our every waking moment and display it to everyone and for everyone.’

‘Sounds hellish,’ said the headmaster. ‘I can’t think of anything worse.’

He was looking around.

‘What do you think, Sefton?’ said Morley.

‘It’s fascinating, Mr Morley.’

‘Yes, I wonder if we might set up something similar back at St George’s. What do you think?’

‘I think it’d be a marvellous idea,’ said the headmaster.

‘Absolutely,’ I agreed.

‘Alex has it set up rather nicely,’ continued the headmaster.

‘Indeed,’ said Morley. ‘Home from home. We should probably take notes, Sefton: list of materials, etcetera?’

‘Yes, of course,’ I said. ‘I wonder if I might … ?’ I indicated the drawers and cupboards. ‘Just to see how it’s all set up?’

‘Of course,’ said the headmaster. ‘Absolutely fascinating actually, isn’t it?’

And so I began opening drawers and cupboards.

‘Now what about these?’ said the headmaster. On a shelf, beside some jars of chemicals and powders, there were a number of figurines.

‘Interesting,’ said Morley. ‘Egyptian gods and goddesses?’

‘Seem to be,’ agreed the headmaster.

They passed the little objects between them, holding them up close. I continued – calmly – rifling through drawers. I was very keen to find Mrs Dodds’s photographs.

‘What have we here?’ asked Morley.

‘An ibis-headed Thoth?’ said the headmaster.

‘Indeed,’ said Morley.

‘Ivory, I think.’

‘Rather lovely,’ said Morley. ‘Anything interesting, Sefton?’

I had alas found nothing interesting – or rather, plenty that was interesting, but nothing specifically of interest to me or Mrs Dodds.

‘And a Horus,’ said the headmaster, picking up another ornament.

‘Of course a Horus,’ said Morley. ‘And a fine specimen. He has good taste, I’ll say that for him.’

‘And a …’ The headmaster drew a blank. ‘Not sure. What do you think?’

‘A lion-headed Sekhmet, if I’m not mistaken,’ said Morley. ‘Any idea, Sefton?’

I glanced up from a drawer. ‘No idea,’ I said.

‘But again very nice,’ said the headmaster. ‘Very nice indeed.’

‘Quite so,’ agreed Morley. ‘Nice little set-up Alex has down here, eh?’

‘Very nice,’ said the headmaster.

‘Very nice, Mr Morley,’ I agreed.

Another drawer full of equipment: tongs, scissors, paper …

‘You know Zola of course described himself as a martyr to photography?’ said Morley.

‘Did he?’ said the headmaster.

‘Oh yes, absolutely obsessed with it. One can see why. I do think the art of photography might in years to come be regarded as an art form like the novel: a combination of documentary realism and fiction.’

‘I can quite believe it,’ said the headmaster.

‘Might be worth an article, Sefton, what do you think?’

I did not reply. Beneath a pile of paper I had found a large brown envelope. The two men continued talking, admiring the set-up, debating what various pieces of equipment might be used for while I reached into the envelope – and my hand touched some thick and glossy papers. I turned my back to Morley and the headmaster and began to draw the papers slowly out of the envelope.

‘Ah, what have we here?’ said Morley, looking over my shoulder. ‘Photographs, eh, Sefton?’

‘Possibly,’ I said, guiltily.

‘Well, let’s have a look, shall we?’ said Morley.

And he and the headmaster gathered round to look.

‘Oh,’ said the headmaster.

‘Well, well,’ said Morley. ‘What do we have here?’

‘What on earth are these?’ said the headmaster.

‘Tarot cards,’ said Morley decisively, which they were indeed. Several packs in fact. ‘Hmm,’ he said, spreading them out on the bench. ‘Marked and unmarked. Someone is clearly taking their Tarot seriously. Mr Eliot would doubtless approve.’

‘Mr Eliot?’ asked the headmaster.

‘Sefton’s friend,’ said Morley. ‘T.S.’

T.S. Eliot was not in fact my friend, or even an acquaintance, though Morley himself had met him on several occasions. ‘Very smooth,’ had been his verdict. ‘Cold hands. Direct gaze. Manners of a saint.’ It was not, I thought, an entirely whole-hearted endorsement.

‘I don’t know Mr Eliot, I’m afraid,’ said the headmaster.

‘Poet,’ explained Morley. ‘Former banker: not a recommendation. Currently I believe panjandrum-in-chief at Faber and Gwyer, is that right, Sefton?’

‘Faber and Faber,’ I corrected him.

‘As I believe they are now known, yes.’ He was extracting cards from the pack as he did so, examining their garish colours. ‘Though there was only ever one Faber, Sefton. Geoffrey Faber? Do you know him?’

‘I can’t say—’

‘Curious chap. Doubled-up his name for the sake of euphony after he and my friends the Gwyers went their separate ways.’

‘Ah.’

‘Anyway, Madame Sosostris I believe, isn’t it, in The Waste Land? Sefton?’

‘Yes, that’s correct.’

‘Lot of nonsense, of course.’ He began laying out the cards on the bench in a pattern. ‘What is it, “Madame Sosostris, famous clairvoyante, wisest woman in Europe with a wicked pack of cards.”’

‘Something like that,’ I said.

He finished laying out the cards.

‘“Wicked”, would you say, Sefton? Or childish, rather?’

‘I’m not sure.’

‘No. Now, would you care to give us a reading, perhaps?’ He pointed to the cards, one by one: ‘High Priestess; Magician; 10 of Cups; Queen of Wands; the Devil; 8 of Wands; 2 of Cups; Wheel of Fortune; Judgement; and the Knight of Swords.’

I looked at them. It was just a random pattern.

‘Any thoughts at all?’ he asked.

‘No.’

‘No. Like your friend Mr Eliot you seem to have an ignorance of the exact constitution of the Tarot pack. Do you know if Alex is interested in the occult sciences at all, Headmaster? Or one of the boys perhaps?’

‘Not as far as I’m aware,’ said the headmaster. ‘But you know what boys are like. They pick up these odd sorts of things and …’

‘Quite,’ said Morley.

These were indeed odd sorts of things but I still hadn’t found the photographs I was looking for. I was now up on a stool, going through the uppermost shelves.

‘Well, anything interesting up there?’ asked Morley.

‘Notebooks, mostly,’ I said.

‘Notebooks,’ he said. ‘Hmm. Well, come on, man, let’s have a look.’

I brought down a clutch of innocent-looking school notebooks. Morley ran a finger over their covers, looking for dust.

‘In regular use,’ he said. ‘And yet set up so high. One might almost suspect that they were not meant to be seen.’

To my eye, there seemed to be nothing remarkable about them: they were standard school notebooks. Except that where usually the cover might read ‘History’ or ‘Mathematics’ these read ‘Formula for Personal Spiritual Development’, and ‘Astral Explorations of Past Lives’. ‘Notes on Astrology’; ‘The Twelve Tribes’; ‘Clairvoyant Investigations’; ‘Horoscopes’; ‘Seances’; ‘Psychic Experiments’.

‘Fascinating,’ said Morley. He flicked quickly through one, and then another. The headmaster examined some of them also, and I rifled through the pages of some others. All the books seemed to be written in code. And they all contained diagrams, sketches of gyres, phases of the moon, disorganised material generally.

‘Interesting,’ said Morley.

‘Really?’

‘It’s code. Yes. Seems to be. Do you recognise the handwriting at all?’

The headmaster studied the books. ‘I’m not sure. It could be one of the boys, I suppose.’

‘Or a teacher?’

‘Possibly. Should we be worried?’

‘I think it all rather depends on whether our amateur occultist sees themselves more as a psychic or as a mystic,’ said Morley.

‘Is there a difference?’ asked the headmaster.

‘Yes, there certainly is, Headmaster. There is indeed. A psychic receives messages, sometimes unwillingly, and certainly unbidden. A mystic, on the other hand, goes seeking the divine.’

‘Bad as each other, then?’

‘Not quite, no. Psychics, I find, are perfectly harmless, on the whole – rather entertaining, often. Cranks, but harmless cranks. Individualists. Eccentrics. Wonderful woman down in Clacton … But mystics … Mystics tend rather towards the malevolent, in my experience. And they like to band together to cause mischief. Not a lot to be said in their favour.’

Morley was now digging deeper into some of the cupboards and produced some bits and pieces of religious paraphernalia. A crucifix. A bottle of holy water.

‘Anything missing from the chapel, Headmaster?’ asked Morley.

‘I have no idea.’

‘Might be worth checking.’

‘Mr Morley?’ I said. I was up on the stool still: there was another shelf of books below the shelf containing the notebooks. ‘Do you want to look at everything?’

‘Yes, yes, let’s have them all down, Sefton, if you please.’

There were paperbacks and some books in soft leather linings. I passed them down to Morley.

‘What have we got here then, gentlemen? Montague Summers, eh, The History of Witchcraft and Demonology? Now we’re getting somewhere! Montague Summers, indeed. Excellent little guide.’ Morley flicked through the pages of the book. ‘Though the problem with Summers of course is that he actually seems to believe in the witch cults.’

‘You do seem terribly familiar with all this material, Morley, if you don’t mind my saying so,’ said the headmaster.

‘“Moses was learned in all the wisdom of the Egyptians,”’ said Morley. ‘The Book of Acts, is it? Occult knowledge: it is tempting, I suppose. For a moment. And I have read widely – or as widely as one might need – in the alchemists, the Gnostics, the Hermetists, Neoplatonists and what-not, but I can’t honestly say I’ve found that much there that one might not find in Plato’s Timaeus. Also, do you know Mr Watkins’ bookshop on Cecil Court?’

‘In London?’

‘Off Shaftesbury Avenue,’ said Morley. ‘You know it, Headmaster?’

‘Cecil Court, yes. I think I’ve taken Mother down there a few times. Not the bookshop though, I don’t think.’

‘It’s rather “interesting”, as Sefton might say. They hold these little soirées. I went along to a few, after my son … Anyway. Tea, cake and theosophy. Makes for a pleasant enough sort of evening. I have struggled my way through the works of Eliphas Levi, and MacGregor Mathers. Max Müller’s books on the sacred texts of the East. They’re all after the same thing essentially.’

‘Which is?’

‘Power, of course. The idea of transforming oneself into a magus. Solomon the Mage, Simon Magus, Comte de Saint-Germain. Etcetera. No shortage of the blighters. The magus, the sorcerer, the alchemist: all of them seized with an obsession, a desire for greatness. Insight. Power. Wisdom. They think by force of will they might somehow achieve that which is impossible. Short cuts to knowledge. We know that often men wish for knowledge because power attends it; they strive for knowledge not for its own sake, but in order to attain power. Seized with such a perverted desire, men become demented. I have seen it oftentimes among university professors. Politicians are prone to the same fantasy, of course. Total control. Command.’ Morley paused. ‘Hmm. Are there people in the school who you think might be susceptible to this dangerous sort of fantasy, Headmaster? The idea that they might rightfully rule?’

‘I really don’t know, Morley.’

‘The spurned lover? A man overlooked for promotion or cheated of some sort of preferment? The man who sees himself as the rightful … Is Alex the only person with keys to the darkroom?’

‘Apart from me,’ said the headmaster.

‘And your keys have mysteriously disappeared?’

‘Or been misplaced.’

Morley fell silent. The atmosphere in the room had changed. As Morley had been talking the headmaster had been absent-mindedly going through one of the notebooks, where he had found a set of negatives, which he was now holding up to the red safelight.

‘Ah,’ said Morley. ‘Well spotted, Headmaster! At last! Some photographs. I was beginning to wonder what Alex used the room for!’

It became clear, at that moment, what Alex used the room for.

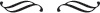

They were photographs, mostly of women – naked women. In the negatives of course their skin was jet black, and the hair – and pubic hair – a quite startling white.

Photographs, mostly of women

‘Well well,’ said Morley.

‘Oh dear,’ said the headmaster.

Several of the negatives were indeed of Mrs Dodds. She was quite right: they were not photographs that her husband would have been pleased to view.

‘Well … only to be expected perhaps,’ said Morley. This was, I think, the only occasion during our time together that I saw him blush – though it may simply have been the red light. ‘New technologies always lend themselves to – shall we say – fleshly uses. You know that many of the first pamphlets published after Gutenberg were nothing more than scurrilous …’

But there were also photographs of men. With other men.

‘Is that the chaplain?’ I said.

‘I rather fear so,’ said Morley. ‘Headmaster?’

The headmaster seemed to have lost all his strength; he collapsed down upon himself, onto the stool on which I had been standing, collapsing like a boxer returning to his corner and throwing in his towel, a gesture of total defeat. Morley turned his back to me slightly and laid a hand upon the headmaster’s shoulder – and in the same instant I laid my hand upon the negatives of Mrs Dodds and was about to put them into my pocket for safekeeping. But Morley had noticed me reaching out for them and grabbed my wrist with one hand, snatching the negatives with his other. His strength was quite astonishing.

‘Sefton?’

‘I …’

‘What do you think you’re doing, man?’

‘I was just going to …’

‘You were going to what?’

‘I was just going to look after them.’

‘And why do they need you looking after them?’ asked Morley.

‘They need destroying,’ said the headmaster bitterly, his head in his hands.

‘I’m afraid it may be too late for that, Headmaster,’ said Morley. ‘And I think you may have some explaining to do, Sefton. Do you want to tell us why you were interested in coming down here?’

I said nothing.

‘Sefton?’ repeated Morley. ‘You’d better speak up, man.’

‘I happened to have mentioned to someone that I was interested in the darkroom and they said that Alex had … asked them to become an adept.’

‘Someone happened to mention to you that Alex had asked them to become an adept?’

‘Yes.’

‘And you didn’t see fit to mention it?’

‘No, I …’

‘You may have wasted us precious time, Sefton.’

‘But I thought … Alex was the hero of the hour and—’

‘Who might this person be, might I ask?’

‘An acquaintance,’ I said.

‘Sefton?’

I remained silent.

‘Headmaster?’

Morley was holding up my negatives to the light.

‘The face here looks familiar, but I can’t quite think … Headmaster? This might be important. I need you to …’

The headmaster glanced up. He recognised her straight away. ‘Mrs Dodds,’ he said. ‘It’s Mrs Dodds, Morley.’

‘And she is?’

‘She’s the wife of our benefactor. Mr Dodds, who has enabled us to buy the new school.’

‘And the others are?’

‘Mostly other benefactors.’

Morley was pacing up and down now. ‘Oh dear, oh dear,’ he said. ‘Oh dear, oh dear.’ He held up the negatives to the safelight. ‘Sefton, what exactly did your Mrs Dodds say about Alex?’

‘She said that he had asked her to become an adept.’

‘And that’s all?’

‘And that Alex claimed he was some sort of … mage?’

‘Come on, Sefton! And you didn’t think to pass on this information?’

‘I—’

‘You can never trust a man who calls himself a mage,’ he said.

‘But you call yourself the People’s Professor,’ I said.

‘Not a title I claim for myself, Sefton. It’s merely a shorthand, for the newspapers.’

‘Do you think he’s a devil worshipper?’ I asked. ‘Alex?’

‘You’ve clearly been watching far too many movies, Sefton. Only fools believe in devil worship. And only idiots believe in devil worshippers.’

‘So—’

‘I think it’s more likely he’s someone who believes in the perfectibility of man’s soul. In developing full human potential. Do What Thou Wilt Shall be the Whole of the Law and etcetera. Love is the Law, Love under the Will.’

‘Sorry?’ I said.

‘He was never the same after the war,’ said the headmaster, interrupting, lost in his own thoughts. ‘He was always … looking for something.’

‘Which is why you moved here?’

‘Mother thought it would be a good idea to move the school here.’

‘Because?’

‘I think … I thought she just wanted a view of the sea. But Alex had these grand schemes and plans. He was able to persuade all these benefactors. I thought it was …’

‘And you knew nothing about it?’

The headmaster was silent.

‘Well,’ said Morley, clearing his throat, ‘let’s just see if we can establish exactly what’s going on here, shall we?’ And then having peered at the photographs for a moment, he suddenly swung around and pointed over the doorframe.

Inscribed over the door, in the dark I could make out black-painted letters, SATOR AREPO, set out in a pattern:

SATOR

AREPO

TENET

OPERA

ROTAS

‘That,’ said Morley.

‘What?’

‘In a lot of the photographs. The Sator Arepo, from the testament of Solomon. Magic palindrome. Now, if we have the Sator Arepo, we’re probably going to have …’ He looked down at the floor. ‘Move out of the way, Sefton.’

There were markings on the floor.

‘Damn!’ said Morley. ‘Damn!’

‘What is it?’ asked the headmaster.

‘This,’ said Morley, indicating some markings on the floor, ‘this is the Tree of Sephiroth, if I’m not much mistaken.’

‘Which means?’

‘It means that this is some sort of chamber.’

‘What sort of chamber?’

‘Wasn’t there a notebook there, Sefton, that said something about the moon?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Just have a look. Ephemerides tables, that sort of thing? Saturn in the ascendant? Mercury triune to the ascendant? Saturn and Uranus triune to the moon? It’s not a full moon by any chance tonight, is it?’

‘It is, Mr Morley, yes. I think so.’

‘Which means our occultist friends will be active exactly’ – Morley checked his watch with the luminous dial – ‘around now.’

‘But there’s nothing happening here,’ I said. ‘You couldn’t swing a cat in here.’

‘No. But a cockerel maybe,’ said Morley.

‘A cockerel?’

‘Or a hen.’ He pointed to stains on the floor. ‘Mr Gooding’s missing chickens?’

‘What on earth are you suggesting, Morley? That—’

‘They’d really need bigger premises,’ continued Morley. ‘Somewhere private. And if you were involving the boys …’

We began running upstairs to the dormitories.