By 1918 the US had declared war on Germany, thus entering World War I. The situation in Mexico had been terrible since the beginning of the revolution in 1910. While fighting the Germans overseas, US forces still had an obligation to defend the United States’ southern border. Border excursions did occur after the troops returned to the United States – there were small engagements at Buena Vista, Mexico (December 1, 1917), San Bernardino Canyon, Mexico (December 26, 1917), near La Grulla, Texas (January 8–9, 1918), Pilares, Mexico (March 28, 1918), Nogales, Arizona (August 27, 1918), and near El Paso, Texas (June 15–16, 1919). However, they were not as effective or notable as those that led up to the Columbus raid in 1916 – with the exception of Nogales, where US forces were engaged in combat with a federal Mexican garrison occupying Nogales, Sonora, and a group of German military advisers.

For years, the Yaqui native Americans struggled against Mexico in hopes of establishing an independent state in northern Sonora. In 1918 the fight was still at hand. Yaquis, being poor peasants, would smuggle themselves across the border into Arizona, where they traveled to Tucson to find work in the orange groves. Upon payment, the Yaquis would purchase weapons and return to Mexico to fight their war. In 1917, American farmers and ranchers began reporting sightings of armed native Americans and butchered livestock in their grazing ranges, which prompted the United States Army to conduct border patrols in the area. Yaqui natives had constructed a base in Bear Valley, along trails widely used by travelers passing to and from Mexico. The natives positioned their camp on a ridge inside the valley.

On January 9, 1918 a small force of US 10th Cavalry soldiers detected a band of over two dozen Yaquis hiking up to their camp. At some point the Yaquis discovered the advancing Americans and hastily began to withdraw, leaving behind ten men to protect their retreat. The US Cavalry stopped and then dismounted. The Americans’ orders were simple: deny the Yaquis their base by advancing and capturing their camp. Now on foot, the cavalrymen proceeded up to the camp. Once in range, the Yaquis opened fire with minimal accuracy, as did the Americans. Under fire, the US Cavalry moved forward. For 30 minutes the two forces fought in the classic Indian War style. Both sides relied on natural cover. Eventually the Yaquis surrendered, after their chief was wounded in the chest by a bullet that hit his ammo cartridges, triggering an explosion that left an open wound.

No Americans were killed that day but some were reported to have minor injuries. The Yaquis, one of whom was ten years old, were captured and the US Army gave aid to the wounded natives. On their way back to Nogales, the Yaqui chief died of his injury. The rest of the natives, except for the boy, were taken back and put in jail on charges of gun smuggling and other minor crimes. Some spent a few weeks in jail but were eventually released.

When asked why the Yaquis fired on the approaching Americans, they replied by saying they thought the American buffalo soldiers involved were Mexicans coming to attack them. The small battle marks the last engagement between the United States Army and native Americans, thus ending the American Indian Wars for good.

Throughout the Mexican Revolution US forces garrisoned America’s border towns, occasionally exchanging fire with Mexican rebels or federals. With the British interception of the Zimmerman Telegram in 1917, the United States knew well of Germany’s attempt to bring Mexico into the war on the side of the Central Powers.

In the beginning of 1918, the US Intelligence Division in southern Arizona began reporting that German agents were teaching the Mexican Army military procedures and building defenses. A few days before the fighting began, an anonymous letter was received by Lieutenant Colonel Frederick J. Herman from someone claiming to be an officer in Pancho Villa’s army. In the message, the unknown Mexican warns Herman of the German espionage in and around Nogales, Sonora. The letter also warns of an attack or raid that was to take place somewhere around the end of August. This increased tension along the border. A squad of German military advisers were training the Mexican Army garrison of Nogales, Sonora, and the American troops stationed in southern Arizona were well aware of their operations.

On August 27, 1918, at about 4:10p.m., a gun battle erupted unintentionally when a Mexican civilian attempted to pass through the border, back to Mexico, without being interrogated at the US customs house. The man was suspected of gun smuggling and refused to stop. As he passed the office, customs inspector Arthur G. Barber ordered him to halt. The Mexican failed to halt, leading Inspector Barber to run after him with pistol in hand, followed by two enlisted men. A Mexican officer, on the Mexican side of the border, witnessed the chase, saw Barber with his pistol in hand, drew his own and fired at the customs inspector at or just inside Mexico. The shot missed Barber but hit one of the soldiers, killing him instantly. The other enlisted man then raised his weapon and fired, killing the hostile Mexican officer. After the initial shooting, reinforcements from both sides rushed to the border line. Hostilities quickly escalated.

When the US 35th Infantry garrison of Nogales requested reinforcements, the Buffalo Soldiers of the 10th Cavalry, commanded by Frederick Herman, came to their aid from their camp outside of town. After observing the situation for a few moments, Lieutenant Colonel Herman ordered an attack south of the border to secure the Mexican hilltops overlooking the Sonoran border town. Defensive trenches and machine-gun placements had been seen being dug on those hilltops during the previous weeks. Herman wanted his forces to occupy the position before Mexican reinforcements got there.

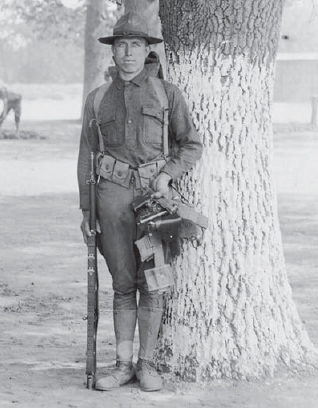

An American infantryman displaying his equipment consisting of his Model 1903 Springfield Rifle (.30-06 Caliber) and two Model 1911 Government Pistols (.45 ACP). (AdeQ Historical Archives)

Under heavy fire, the US infantry and dismounted cavalry advanced across the border through the buildings and streets of Nogales, Sonora, and up on to the hilltops. Some armed Arizona citizens tagged along, but most US militia stayed on the American side, firing their weapons from their house windows. Individuals dressed as Mexican civilians and armed with military rifles helped fight the Americans.

About 7:45p.m., the Mexicans waved a large white flag of surrender over their customs building; Lieutenant Colonel Herman then ordered an immediate ceasefire. Snipers on both sides continued shooting for a little while, but were eventually silenced upon orders from their superiors.

Because the battle began as a minor shooting incident and not as a full-scale assault the situation was quickly deescalated. The Americans claimed that the Mexicans and their German advisers were defeated before they could launch their supposed attack or raid into the United States. This was the last hostile action in the border conflict known as the Border War from 1910 to 1918.

The US Army suffered three dead and 29 wounded, of which one died later of wounds. Arizona militia and civilian casualties were two dead and several wounded. According to the US Army, the graves for 129 Mexicans were dug. However, Mexican casualties reported in various newspapers ranged from 30 to 129 dead or wounded in action. The bodies of two German advisers were recovered and examined by the Americans before they were buried. It was reported that other German advisers fled southward. Never again were there reports of Mexican troops massing on the Arizona border or German soldiers and or advisers in the border region. After the battle, German military activity in northern Sonora ceased and the consequences of the incident were settled diplomatically. This was the only land battle fought between Germans and Americans in North America.

One of the last actions taken by the United States Army during the Mexican border conflict occurred when the 24th Infantry stationed in El Paso took up positions at the Santa Fe Street Bridge on the evening of June 15, 1919. In addition the regiment manned armored machine-gun trucks with crews from the machine gun company. Considerable firing in Juarez was reported by the regiment and several stray bullets struck the Immigration Building where the regimental headquarters were set up. By 3:15a.m. reports were received that all of Juarez, with the exception of Fort Hidalgo, were in possession of the Mexican rebels. By 4a.m. firing resumed in the vicinity of the fort and within 30 minutes the flashes of the rifles advanced within 800 yards of the Santa Fe Bridge. Bullets began falling on the American positions, wounding two soldiers. By 5a.m. federal troops had retaken the positions on the Mexican side of the bridge.

An advance guard from the 24th Infantry crossed into Mexico by 11:45p.m. to face Villista forces near the race track. There the Villistas fired upon members of Companies E and G and the Americans returned fire. One American was wounded and another killed in the encounter. Juarez was retaken and occupied by the 24th until the following day, when the US forces were ordered back across the border. The regiment reported back to Camp Owen Bierne by 11:30a.m. By June 25, 1919 the regiment was moved to Columbus, New Mexico. With the main phase of the Mexican Revolution ending in 1920 further tensions and potential conflict along the Mexican–American border had been reduced.

The morning headlines of the Albuquerque Journal on August 28, 1917 told the story in one brief statement: “Seventeen Mexicans in the Columbus Raid Guilty in Second Degree.” Previous to the conviction of the 17, four Mexicans who had been captured following the raid were executed by hanging in Deming, New Mexico. The execution took place less than four months after the Villista Raid on Columbus, New Mexico. They were put to death in pairs, with Eusevio Renteria and Taurino Garcia being placed on the scaffold first. Twenty minutes passed before they were pronounced dead. Jose Rangel and Juan Costilla were next, and they died instantly. No evidence was ever introduced in the trial of the four Villistas that connected them directly with the killings in the Columbus raid. However, these four suffered the consequences of Villa’s attack with their lives.

Weeks after the raid a punitive expedition led by General John J. Pershing was organized to find Villa and his men. Approximately 19 had been captured, although a few had died while in captivity. Handcuffed, heavily guarded, and still suffering from the wounds inflicted by Pershing’s troops, on the day of their conviction 17 Villistas showed the affects of long confinement in the Silver City jail. The men pleaded guilty to the crime of second-degree murder and were sentenced to serve from 70 to 80 years in the penitentiary. District Judge R. R. Ryan of Silver City handed down the sentence. As the men were 25 years of age or more they faced the prospect of life in prison. The life sentence was not widely accepted by the American press or the public; nothing short of the death of Pancho Villa and everyone involved in the raid would appease them.

American soldiers guarding Villistas prisoners during the Punitive Expedition. Many of these prisoners were handed over to law enforcement officials of the state of New Mexico. Their status was later debated: whether they were to be regarded as bandits or as soldiers, thereby granting them a protected status as prisoners of war. (AdeQ Historical Archives)

In this hostile and turbulent atmosphere of vengeance, New Mexico Governor Octaviano A. Larrazolo was presented with a request for the pardon of 15 of the convicted Villistas. The year was 1920 and it was only his second year in office. Governor Larrazolo, Mexican born, Republican, and no stranger to controversy, was determined not to bend before public and political pressure in what he saw as his moral duty to pardon the Villistas. The same man who declared martial law in McKinley and Colfax counties during the coal strike of 1919 prepared an eloquent defense on behalf of the Villistas captured in the Columbus raid.

In reviewing the transcript of the trial, Larrazolo was appalled by the proceedings in the district court case of New Mexico vs. Eusevio Renteria et al., in which the prosecution failed to present any concrete evidence to connect the defendants with the murder of Charles D. Miller, an American victim of the raid. The jury, which consisted of 12 white males, took only 30 minutes of deliberation to arrive at a verdict of guilty of murder in the first degree. It was obvious to Larrazolo that the testimony of the defendants carried little weight in the eyes of the jury. District Attorney J. S. Vaught, in selecting the jurors, asked each man on the panel the following question: “If it should develop in this case that the state should fail to show that either one of these defendants or all of them fired the fatal shot which killed Mr. Charles D. Miller, but that they were present at the time this man was killed and assisted in his killing by aiding and abetting in the commission of this murder, would you then return a verdict of murder in the first degree?” The answer by each juror was, “Yes, sir!” The second question was, “You would, knowing that it carried the death penalty?” One by one, potential jurors who indicated that they had reservations or were hesitant to answer “yes” to the second question were immediately dismissed. In this way, the jury was selected and the trial began. The opening remarks of J. S. Vaught, quoted here verbatim, set the tone for the trial. “The state in this case expects to prove to you that on the morning of the ninth of March, 1916, one Charles D. Miller was killed at Columbus, and we expect to prove this to you by the admissions made by these defendants. We do not expect to show you that either of the defendants fired the shots that killed Charles D. Miller, or that they were close by the place where Charles D. Miller was killed, but at the time he was killed, they were in that immediate vicinity assisting in the commission of a felony.” In other words, the defendants in this case labeled “Villistas” would be convicted and hanged for murder because they were in the town of Columbus on that day.

Several of the defendants testified that they were forced, by the threat of being killed by Villa, to join his forces. Taurino Garcia testified that he was working as a mason when Villa rode up to him on his way to Chihuahua and forced him to join his army. When Garcia resisted, Villa and his men formed a ring around him, beat him severely with a spade and locked him up for six days without food. Upon his release Garcia was turned over to General Beltron for conscription into Villa’s army. Villa’s orders were to kill any man who refused to serve. Governor Larrazolo was fully aware of the circumstances that brought many of these men to Columbus and their destiny. For this reason and others, he prepared an executive order for the pardon of 15 of the 17 Mexicans convicted on August 17, 1917. He was determined to expiate these men and to save them from the fate suffered previously by their countrymen in Deming.

The defense prepared by Larrazolo on behalf of the Villistas was benevolent as well as legally sound, following logical legal precedents. He began by describing the movement of the troops into Columbus and reviewing the results of the fighting. He placed his emphasis on the acknowledgement that all the men were common soldiers. He recognized “that all of the defendants were in the ranks of the Villa invading columns, and were all subsequently captured in Mexico by our troops, and having been brought into Luna county, New Mexico, were there indicted, charged with the crime of murdering the people that were killed at Columbus at the time of the assault on the morning of March 9, 1916.”

Larrazolo asked that consideration be given to the conditions and circumstances under which these men acted: “Were we at peace with the Republic of Mexico or did a state of war exist between the United States and Mexico?” He proceeded to demonstrate that a state of war did actually exist at the time of the Columbus raid. A battle between the United States and Mexico had taken place in Veracruz on April 21, 1914. Following the fighting, the United States remained in possession of the port and city for approximately seven months. Larrazolo, was quick to acknowledge that no actual declaration of war was made, but emphasized that a state of war may exist between nations without a formal declaration of war being made from either side. Because the United States and Mexico were in a state of war, the treatment of the Villistas was material within the framework of the law: the men were in fact prisoners of war and should have been treated and dealt with according to the rules of military engagement. More importantly, Larrazolo argued, civil courts had no jurisdiction in the case.

The April 24, 1916 edition of the New York Times reported: “Pablo Lopez, who commanded the Villa bandits that massacred seventeen Americans at Santa Ysabel, Chihuahua, was captured in a cave a short distance from Santa Ysabel today by a detachment of Carranza soldiers, and is now being taken to Chihuahua City with three of his bandit followers for execution, according to a message from Santa Ysabel received by General Gabriel Gavira at Juarez this afternoon.” (AdeQ Historical Archives)

An image purporting to show the body of Pablo Lopez being displayed by American troops. It is highly unlikely this is of General Lopez and has probably been misidentified. (AdeQ Historical Archives)

Larrazolo’s defense of the Villistas raised several other legal and moral considerations. After personally cross-examining each of the men involved he discovered that most of them were illiterate, that they were laborers, and they were forced into service against their wills. Larrazolo defended their position in this way:

It is a fact known to the average laymen, and even the most ignorant of us, that under military discipline, the common soldier, known as a private in the ranks, is never told what the objectives of any military movement is, particularly so when engaged in hostilities. The absolute, unconditional, and passive obedience of the common soldier to his superior officers is so generally known, so well established, and so relentlessly enforced, that it has been a theme for the poet, who speaking of this soldier’s obedience to superior officers says: ‘It is not for him to ask the reason why. It is for him to obey and die.

The governor then proceeded to review the history of the turmoil in Mexico at that time. He strengthened his defense by describing the campaigns of General Francisco Villa, and the revolutions and counter-revolutions in which he was involved. He emphasized that Villa was indeed the commander of an army and had been in command for ten years. The army under his control maintained rank and file, enforced military discipline, and appointed trained officers whose orders were to be obeyed. It was the Villistas’ duty under military discipline, Larrazolo pointed out, to obey the orders of their superiors. That order, on the morning of March 9 in Columbus, was to fight the enemy.

To bolster his defense, Governor Larrazolo documented several important legal precedents established in the case of Arce et al. vs. State of Texas. A detachment of Mexican troops attacked United States soldiers on the Texas side of the border and in the ensuing battle there were casualties on both sides. Six Mexican soldiers were taken prisoner, indicted, and charged with the crime of killing William Oberlies, a United States soldier. They were tried, convicted of murder in the first degree, and sentenced to death. The case was appealed. The Criminal Court of Appeals for the state of Texas handed down the following summarized opinion:

From their testimony, a general statement may be made to the effect that these Mexican soldiers were controlled by their officers in command and were obedient to them; that the command was organized under the authority of the Carranza or de facto government of Mexico and was in fact, a military command. By this testimony it seems that in such circumstances, the soldiers must obey the order of their superiors, and failure to do so would subject them to discipline which rates from minor punishment to death, according to the rule which has been violated by those under its authority. When a soldier is ordered to fight, it is his duty to do so. If he deserts under certain circumstances, he may be shot or executed. At least one of the defendants claimed to have been forced to go into battle by his commanding officer. He did not desire to fight, but under the rules of warfare if he deserted, he would be tried and he would be shot, or if he disobeyed orders and failed to engage in the fight he might forfeit his life. If the state courts had jurisdiction of these defendants, we are of the opinion the conviction would be erroneous. In this case, we are of the opinion that this judgment should be reversed, and the cause remanded.

Upon completing his defense of the Villistas, Governor Larrazolo issued an executive order, released on November 17, 1920, containing a statement that granted to each defendant named a complete, unconditional pardon for the crime of murder. A number of negative reactions to the pardon were received by the governor, though some were more favorable, including the support of A.B. Renehan, a prominent attorney and figurehead of the period. In spite of tremendous pressure from many directions to reverse his decision, Governor Larrazolo stood firm. The Villistas were set free, re-arrested, retried for murder, and acquitted by a jury on April 28, 1921. Sixteen freed Villistas were returned to Mexico on April 30, 1921.