TWO CITY IN PROGRESS

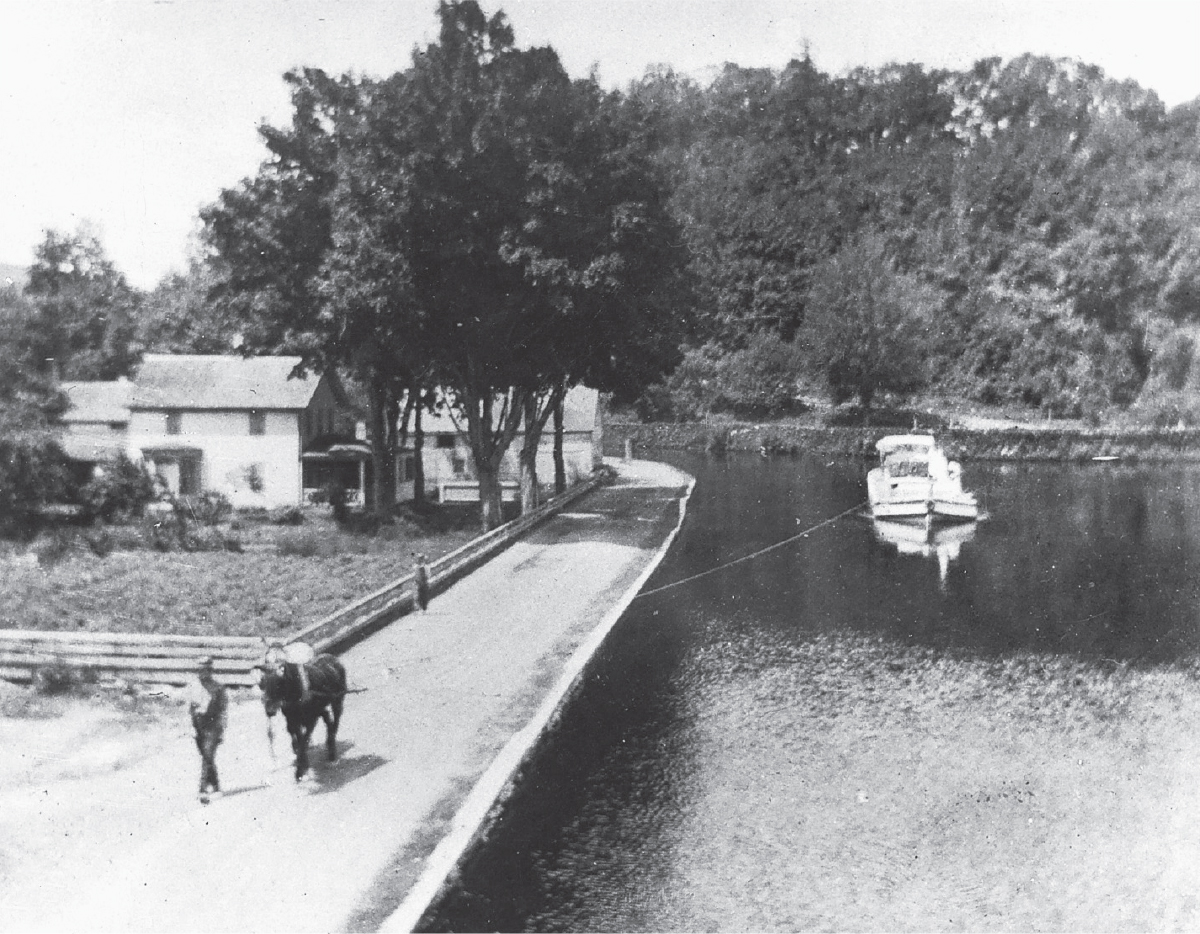

The village took its name from John B. Jervis, the chief engineer of the 108-mile-long Delaware & Hudson Canal, a technological marvel of the 1820s, dug to carry anthracite coal from Pennsylvania through Port Jervis to Rondout, south of Kingston, New York, from where it went by Hudson River barge to New York City. The canal’s importance to the town’s early life is reflected in the fact that the “Port” in its name alluded not to the two major rivers that met there, which were too shallow for commercial navigation, but rather to the manmade D&H. Some 1,600 boats passed through the canal each year, mostly coal barges, but some carrying lumber or other materials. There were occasional pleasure cruises; one converted barge, the Fashion, boasted a dining room, carpeted floors, and room to accommodate a hundred passengers. We can assume the ride was leisurely, as the canal vessels were drawn by mules led along the towpath and rarely exceeded three miles per hour. Known locally as “the Ditch,” the canal wound directly through Port Jervis and featured prominently in village life. Children swam there in summer and skated on its frozen surface in winter; lovers strolled along its towpath. Once in a while an inebriate fell in and required rescue.

(Collection of the Minisink Valley Historical Society)

The Erie Railroad arrived in 1848 and soon located its extensive machine shops in Port Jervis, creating what eventually became one of the largest industrial complexes in lower New York State. By 1892, there were two railroad stations: the Erie, on Jersey Avenue, parallel to the Delaware, and a smaller depot on East Main Street for the Port Jervis, New York, and Monticello Railroad. The latter was commonly known as the Monticello Line for its service to neighboring Sullivan County. With the Erie’s twenty daily through trains between New York City and Chicago, Port Jervis was an important regional station stop and something of a final west-looking outpost of the Atlantic Seaboard, the point after which rail travelers entered the wild beauty of the upper Delaware, then the quilted farms of Western New York and Ohio, and eventually the Midwestern plains.

In a community of just over 9,000 people, more than 2,500 men worked on the rails as engineers, brakemen, firemen, or flagmen, or in the Erie shops. Railroad work, though relatively well paid, was frequently dangerous, at a time when individual workers, not their employers, largely assumed responsibility for their own safety. Headlines of railway misfortunes—CRUSHED BY THE WHEELS; STEPPED IN FRONT OF A TRAIN; A MISPLACED SWITCH—ran almost daily in the newspapers’ inner pages. “The men themselves appear not to appreciate the chances of death and injury incurred by entering the train service,” commented the local Tri-States Union in an 1892 article titled SLAUGHTER OF RAILROAD MEN. The coupling, uncoupling, and braking of trains were the cause of most accidents, although men also tumbled fatally onto the tracks while shoveling coal or walking atop cars. Death might be the cost of a bad footing or a single moment’s inattention.

Lacking adequate warning systems or sufficient separation from public thoroughfares, trains often took the lives of civilians as well—pedestrians cutting through a rail yard or walking along the tracks, and occupants thrown from their carriages by a spooked horse at a grade crossing. One elderly Port Jervis woman was sought by anxious parents almost daily for her skill at plucking the hot cinders that flew from locomotive smokestacks out of children’s eyes. And while no one used the term “noise pollution” in 1892, a strongly worded petition was delivered that year to the Erie Railroad by residents demanding that it “abate the ear-splitting serenades of the railroad and shops” heard at all hours of the day and night.

(Collection of the Minisink Valley Historical Society)

Six days a week the village was all tumultuous industry, home to a silk mill, five bottling works, a tannery, a brewery, and no fewer than eighty-two large and small factories turning out finished products such as lamps, gloves, windows, and stoves. The residential streets were largely unpaved dirt or gravel, but the chief business blocks were laid with cobblestones, and many sidewalks were raised as wooden “board walks,” some partially protected by shop awnings. Culture was not neglected: along with the opera house, the village boasted a music conservatory, a vaudeville theater, and a lending library. Theatrical touring companies played almost nightly. At the opera house, managed by the pharmacist-turned-hotelier George Lea, one could witness a juggling demonstration, a lecture on reptiles, and the peculiar Victorian entertainment known as a “broom drill,” in which sturdy young women armed with brooms instead of rifles performed synchronized military exercises to piano accompaniment. Determined not to be taken for rubes, youthful Port Jervians filled the house in March 1891 to hiss at and catcall a pretender named Professor Archer, who, claiming spiritualistic powers to summon the dead, brought forth from the spectral world the biblical Adam, Longfellow’s “Hiawatha,” and the recently deceased British actress Adelaide Neilson.

Directly to the east of Port Jervis, in the lower half of Orange County, was an area once covered by a glacial ice sheet that, upon its prehistoric retreat, left behind what locals called the Drowned Lands, or the Black Dirt Country—twenty-six thousand acres of wetlands and moist, dark, extremely fertile soil in which almost any crop would thrive. The results included a flavorful species of regional onion as well as grassy pasturelands so lush that Orange County’s dairy products became renowned, its fresh milk a staple for generations of New York and Philadelphia children. The Erie Railroad was said to have made a considerable part of its initial profits in the 1840s transporting Orange County milk to New York City, an enterprise that helped give original meaning to the term “milk train,” as the transports were obliged to make frequent stops at scattered dairy farms.

In the early eighteenth century those who worked the county’s land began to unearth large, mysterious objects from deep in the rich soil. The Boston cleric Cotton Mather pronounced them relics of a race of prediluvian giants; Benjamin Franklin suggested a fossilized molar (of a similar creature found in Ohio) may have belonged to an elephantine creature, now extinct. An 1801 dig in a farmer’s field outside Newburgh, overseen by the Philadelphia artist Charles Willson Peale, resulted in his iconic painting The Exhumation of the Mastodon, and the fossilized skeletal remains of the creature were later exhibited in Peale’s Philadelphia museum. “We think of his majestic tread as he strode these valleys and hill-tops,” mused the Orange County historian Samuel W. Eager of the mastodon, “snuffing the wind with disdain, and uttering his wrath in tones of thunder.” Over the centuries, these megafauna had waded into the bogs of the Drowned Lands to feed on vegetation and had become entrapped in the muck (perhaps, some experts believe, with the connivance of human hunters). So numerous and continual have been the discoveries that many modern paleobiologists consider New York’s Orange County “the Mastodon Capital of the United States.”

Where the retreating glacier did not leave bountiful farmland, it sculpted a brutish landscape of boulder-strewn hillsides, steep escarpments, and the narrow ravine-like valleys the Dutch called “cloves.” These untamable precincts made the region, in colonial times, a kind of early version of the Wild West, with outlaws, highwaymen, and deadly warfare between settlers and Indigenous peoples. “Every lonely road has its tale of tragedy, and every mountain pass its story of encounter with wild beast or savage Indian,” noted one historian. Legends were born of this unrest, such as that of Tom Quick, “the Indian Slayer,” a genocidal murderer who devoted his life to avenging the death of his father at Native hands. And Claudius Smith, a loyalist outlaw hanged at Goshen during the American Revolution, whose skull is said to have later been placed in the facade of the town’s 1841 courthouse. Within present-day Port Jervis lies the scene of the area’s most infamous Indian raid, at a settlement known as Machackemech, where in July 1779 Joseph Brant, or Tyendinaga, a Mohawk military leader and an ally of the British, swept into the Minisink Valley at the head of his band of Tories and Native warriors. After extensive pillaging, Brant and his 90 men retreated to the heights above the Delaware River, where a failed ambush laid by 120 local minutemen resulted in a devastating defeat for the Americans, a massacre that remains sacred regional lore.

On July 5, 1886, Lena McMahon would have gone with her parents and the rest of the village to witness the unveiling of the large monument commemorating the area’s Civil War veterans. Some ten thousand people, slightly more than the village’s population, were said to have joined a three-mile-long parade to Orange Square. There, to the ringing oratory of Lewis Eleazer Carr, the county’s most eminent jurist, the town saluted the local veterans of the 124th New York Regiment, known as the Orange Blossoms, many of whom were on hand. John McMahon had served in a different unit, the 16th Massachusetts Volunteers, a regiment organized at Cambridge, but the 16th and the 124th had shared a role in two major battles—Chancellorsville and Gettysburg.

The town’s rise to importance as a rail and manufacturing center was hailed, at least by itself, a year later, when in 1887 it installed electric streetlamps. It was the first municipality in Orange County to do so, ahead of both Goshen, the county seat, and Newburgh, its largest city—places that one Port Jervis paper had the cheek to dismiss as “backward examples of towns hostile to nineteenth century ideas.” Port Jervis was better able to see its own devotion to progress reflected in its closest neighbor, Middletown, whose State Homeopathic Hospital was one of the country’s most advanced healing centers for mental disabilities, featuring innovations like occupational therapy, an art studio, a patient-edited newsletter, and an athletic program. The Middletown Asylums, a baseball team made up of hospital employees, a recovering patient or two, and numerous ringers, played against competing professional squads. Enthusiastic local fans packed the bleachers on Asylum game days, and the Middletown papers printed box scores and sidebars about the team’s heroes, a few of whom graduated to the major leagues.

That it was considered unsurprising for a psychiatric hospital to field a baseball squad speaks to the broad popularity of the sport during the 1880s and 1890s. “Baseball is the hurrah game of the republic!” cheered the poet Walt Whitman. “[It] has the snap, go, fling of the American atmosphere.” Port Jervis had its own crack teams, although the most renowned were the Red Stockings, African American players who on the Main Street field regularly trounced other local and visiting teams, white and Black. Coverage of their games was laudatory and evinced much local pride. “The whites outnumbered the [Black people] ten to one, but swarms of youngsters of all ages, sexes and color, poured in rapidly, and the crowd mingled freely together, everyone talking and carrying-on, making a perfect Babel of voices,” read the 1885 Gazette article FUN ON THE BALL FIELD: BLACK AND WHITE CLUBS MEET. “[The Red Stockings] are a strong nine, and we will pit them against any colored club in this section. In fact, they are more than a match for a majority of ‘de white clubs.’”

There had long been a modest Black population in the village, due to New York’s long history of slavery. The first eleven Africans to arrive in New Amsterdam landed at the foot of Manhattan Island in 1626. An estimated 42 percent of New York City households counted enslaved persons in 1703, and by 1790, the time of the first United States federal census, twenty-one thousand in New York State—the largest such population in the North, New York City itself having more enslaved people than any other American city except Charleston, South Carolina. The Hudson Valley alone was home to fifteen thousand people in bondage, most laboring as teamsters or diggers, or in some type of river commerce, while others were skilled smiths, coopers, or carpenters. Large numbers of house servants and gardeners were needed to maintain the great Hudson River estates of families such as the Livingstons, the Van Rensselaers, and the Van Cortlandts.

“The two biggest slave markets in the country before the American Revolution were in New York City and Albany,” notes A. J. Williams-Myers, a scholar of regional Black history. “New York was not a society with slaves, it was a slave society, dependent on enslaved Africans.”

While slavery in the Northeast was reputed to be less brutal than in the cotton South, its laws were no less strict, and the British, who took possession of the colony in 1664, were thought far less lenient than their Dutch predecessors. A slave revolt over harsh conditions in New York in April 1712 took the lives of nine white colonists. As a result, twenty-one Black people were put to death. When, in 1741, the mysterious destruction by fire of a fort at the Battery led to rumors of a planned insurrection by enslaved persons allied with poor whites, two hundred people of both races, but most Black, were swept up in arrests. Following a sensational trial, eighteen people were hanged, including a white man and his wife, a second white woman, and an English priest; fourteen others were immolated; and seventy Black people were deported.

Lethal measures were enforced upriver as well. “In 1735 an African slave who resided in Dutchess County named Quacko was sentenced to thirty-nine lashes at Poughkeepsie and an additional forty-eight at Rhinebeck for attempted rape,” recounts Williams-Myers. “Another African, ‘Negro Jack,’ was burned alive in Ulster County in October 1732 for ‘burning a barne and a barrack of wheat.’ And in the town of Kingston, a slave known only as Tom was executed for the attempted rape and the murder of a white woman.” White suspicions about incidents of arson in Albany in 1793 fell on two teenage Black girls, Bett and Deena, who were convicted and executed the following March on the “Hanging Elm Tree,” a local emblem of terror at the corner of State and Pearl Streets that literally loomed over the town’s Black population. An alleged fellow conspirator, a young man named Pomp, was hanged a month later on Pinkster Hill, later the site of the state capitol.

Because they held value in enslaved persons as property, whites were frequently willing to intervene on their behalf when Blacks were accused of petit lawbreaking such as stealing a chicken, gambling, or violating curfew. No such intercession was made, however, to rescue Quacko or Tom for alleged sexual crimes, suggesting that as early as the eighteenth century these offenses were held in special regard. Adulterous white men, accustomed to taking predacious advantage of subjugated Black women, became, in their massive guilt and hypocrisy, fiercely defensive of what they then projected as the flawlessness and purity of white womanhood. Knowing their relations with Black women to be inherently nonconsensual, they chose to believe relations between Black men and white women must be so as well. Black male lust for a white female became in this calculus a vengeful act, a defiance of white male dominance, and a transgression warranting punishment so severe as to blot out the horrible deed itself as well as the perpetrator. In this latter determination, Southern apologists were always quick to point out, red-blooded white men were much alike, regardless of section.

The New York Manumission Society, founded in 1785, had as its members prominent whites such as John Jay and Alexander Hamilton, as well as numerous Quakers. A gradual law of emancipation was enacted by the state, freeing all children born to enslaved women after July 4, 1799, on the condition that they would be retained by the white families who “owned” their mothers and serve as indentured servants, the men until the age of twenty-eight and the women until twenty-five. Unrestricted emancipation in New York arrived by official decree on July 4, 1827. By the early decades of the American republic, however, Northeast textile mill towns such as Lowell and Lawrence, Massachusetts, and Woonsocket, Rhode Island, as well as cities like New York, Boston, and Philadelphia, were part of a global cotton economy supported by enslaved labor, its overseers the Yankee “lords of the loom” and their Southern counterparts, the “lords of the lash.” Partly due to these economic bonds, Northern sympathy for and complicity with the plantation South would persist throughout the antebellum era and into the Civil War.

The Underground Railroad was active in eastern Orange County during the 1840s and 1850s, chiefly in Goshen and the river town of Newburgh. New York City was a center of intense pro- and anti-abolitionist fervor, the scene of confrontations between the Kidnapping Club, corrupt police and judges who conspired to abduct and sell free Negroes, as well as those who escaped from bondage, into Southern hands; and the Committee of Vigilance, led by the Black journalist David Ruggles. Worse trials lay ahead, for with the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, a white man who swore under oath that a Black person was his runaway “property” was entitled to the assistance of federal marshals and U.S. commissioners in returning him or her to bondage. Northern citizens were required to not interfere with the law and, in some instances, to abet its enforcement, and persons caught shielding or transporting a runaway could be fined one thousand dollars. Suspected Black men and women taken into custody had no right to a jury trial, nor were they permitted to testify on their own behalf. Rather, after a cursory hearing before a federal commissioner, they were to be removed to a waiting boat or train and hustled directly “home” to the landowner who claimed them.

Although legend contends that sympathetic Erie Railroad conductors conveniently looked the other way when runaways rode the rails west to Lake Erie, where passengers could cross by ferry to Canada and freedom, there is scant evidence Port Jervis played a significant role. At the time, it likely would not have been safe for a man or woman following the North Star to linger in the village, as amid its small Black population a stranger would not long remain anonymous.

A signal event was the 1857 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Dred Scott v. Sandford. The case involved an enslaved man, Dred Scott, who had been brought from Missouri, a slave state, into Northern territories in which slavery was not allowed. Upon his return to Missouri he sued for his freedom on the grounds that, having set foot in a free territory, he could legally no longer be held in bondage. Rebuffed by Missouri judges, his appeal reached the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled that Black people, in the opinion of Chief Justice Roger Taney, “are not included, and were not intended to be included, under the word ‘citizens’ in the Constitution, and can therefore claim none of the rights and privileges which that instrument provides for and secures to citizens of the United States.” The Constitution, he said, established that “a perpetual and impassable barrier was intended to be erected between the white race and the one which they had reduced to slavery.” In the same ruling the Taney court undermined the premise of the Missouri Compromise of 1820, in which Congress had set limits on the extension of slavery into the western territories. As Abraham Lincoln would argue the following year in his debates with Senator Stephen Douglas from Illinois, Taney’s disastrous ruling laid the groundwork for slavery (as well as the non-personhood of Black people) to become a national reality, in spirit and in fact, not limited to the South or any other distinct region.

The Dutch families of the Lower Hudson Valley, including western Orange County, had been among the white New Yorkers most reluctant to relinquish “ownership” of enslaved people. Some, disdainful of having to lose their “property” without compensation, arranged quietly (and illegally) to send the enslaved south to be sold. Perhaps it was due to this obstinacy, as well as the region’s violent years of settlement and a later territorial dispute with neighboring New Jersey, that Port Jervis long retained a conservative bent. The Tri-States Union editorialized during the 1856 presidential election in favor of maintaining the institution of slavery, and Deerpark, the town in which the village was then formally situated, voted in 1860 by a staggering margin of 664–17 against a state ballot initiative to enfranchise non-property-owning Black men. That same year, it narrowly backed Abraham Lincoln for president, and in 1864, at the height of the Civil War, it voted to deny him a second term, apparently no longer sharing the faith, so eloquently voiced in his first inaugural, that “the mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearth-stone, all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.”

Lynching has existed since the earliest days of the republic. The term derived from the name of a Virginia magistrate, Charles Lynch, the original “Judge Lynch,” known for ordering, on dubious authority, the flogging of Tories during the American Revolution. For many years after, it referred to incidents of nonlethal shaming punishments such as tarring and feathering, or the hauling of an undesirable from a community tied to a fence pole (the origin of the expression “ridden out of town on a rail”).

In summer 1835 there were mob killings of gamblers in Vicksburg, Mississippi, as well as summary executions of Black people alleged to be fomenting a revolt elsewhere in the state. In St. Louis the following year, a free Black man, a steamboat porter named Francis L. McIntosh, fatally stabbed one constable and wounded another while resisting a wrongful arrest; pursued by a white mob, he was seized and put to death by immolation. The local abolitionist editor Elijah P. Lovejoy wrote critically of the lynching of McIntosh and of the inaction of Judge Luke E. Lawless, who, concerned that with abolition “the free Negro has been turned into a deadly enemy,” refused to indict those responsible. Enraged by Lovejoy’s published words, whites sacked his St. Louis office and destroyed his printing press. In November 1837, after he had relocated twenty-five miles upriver in Alton, Illinois, vigilantes again besieged him and his publishing operation, setting his warehouse on fire and shooting Lovejoy dead when he emerged from the building.

What had stirred this intense paranoia and reaction was the filtering from North to South of fierce antislavery sentiment in the form of periodicals, broadsides, and the intensifying of agitation in Congress, making Southern whites fear the destabilization of their society and economy. A singular provocation had been the 1829 publication of David Walker’s Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World. This seventy-six-page assault against slavery, written by a young Black Bostonian, ran through several printings and was disseminated widely in the South, unsettling many a slave owner with its alarming caution: “Remember Americans, that we must and shall be free … Will you wait until we shall, under God, obtain our liberty by the crushing arm of power? Will it not be dreadful for you? I speak Americans for your own good.”

This call for freedom was followed in August 1831 by Nat Turner’s rebellion, in which the visionary preacher and field hand in Southampton, Virginia, having “seen” God’s commands written in the sky, launched an insurrection that killed sixty white men, women, and children, most of whom were dragged from their homes and hacked to death. Turner and his band were captured and executed, but the planter aristocracy slept badly ever after, fearful of a righteously vengeful uprising from the slave quarters and the sound of barefoot intruders on the stairs. An added source of consternation was the appearance that year of The Liberator, published in Boston and soon to become the nation’s leading abolitionist newspaper, in which the printer and Bible-read reformer William Lloyd Garrison committed his life to a frontal assault on the American slave empire and to its utter and final collapse.

It was the murder of Elijah Lovejoy that moved Abraham Lincoln, then a twenty-eight-year-old lawyer, to address the Young Men’s Lyceum of Springfield, Illinois, on January 27, 1838. In his talk, “The Perpetuation of Our Political Institutions,” Lincoln decried “this mobocratic spirit, which all must admit, is now abroad in the land.” He told listeners who had gathered to hear him that winter evening:

When men take it in their heads today to hang gamblers, or burn murderers, they should recollect that in the confusion usually attending such transactions, they will be as likely to hang or burn someone who is neither a gambler nor a murderer as one who is, and that, acting upon the example they set, the mob of tomorrow may, and probably will, hang or burn some of them by the very same mistake. And not only so; the innocent, those who ever have set their faces against violations of law in every shape, alike with the guilty, fall victim to the ravages of mob law; and thus, it goes on, step by step, till all the walls erected for the defense of the persons and property of individuals, are trodden down and disregarded.

Lincoln warned of the sure descent of mob law into anarchism, when the “perpetrators of such acts going unpunished … having ever regarded Government as their deadliest bane,” will “make a jubilee of the suspension of its operations.” He was prescient in noting that mobs taking the law into their own hands

are neither peculiar to the eternal snows of [New England], nor the burning suns of the [South]; they are not the creature of climate; neither are they confined to the slave-holding, or the non-slave-holding states. Alike, they spring up among the pleasure hunting masters of Southern slaves, and the order loving citizens of the land of steady habits. Whatever, then, their cause may be, it is common to the whole country.

Mobs and the extrajudicial punishments they meted out in the antebellum South brought an eloquent rebuke from a future president. However, it was after Lincoln’s death, in the crucible of the untidy postwar years, that lynching became both institutionalized and more consistently lethal. The depravity of the practice was such that while some lynchings were carried out in secret, many were staged spectacles—public executions with dramatic and ritualistic features that in part resembled both a picnic and an outdoor religious revival. Announced beforehand by local newspapers, the incidents drew thousands of white onlookers, some arriving from larger nearby cities such as Atlanta and Charleston aboard special excursion trains, joining the multitude that had come by horse, by buggy, or on foot. The lynching itself typically involved torture, mutilation, and the shooting, hanging, or immolation of a living human being—frequently all three. It was followed by a frenzied competition for relics of the event—a piece of charred tree trunk or link from a chain with which the victim had been bound.

Nor were lynch mobs necessarily sated by the consummation of their goal, but they frequently turned their fury on adjacent Black neighborhoods, looting and torching stores and houses while visiting hellish violence on any Black person unfortunate enough to fall into their path. The impact of such terrorizing scenes on African Americans, whether one mile or one thousand miles away, was profound, enough so to inspire, where feasible, out-migrations to safer precincts and to linger permanently in the psychology of the Black family. It is no exaggeration to suggest that in the dread horror of lynching, of whites’ capricious assaults that might inexplicably leave a son, husband, or brother dead, lies the origins of “the talk,” the necessity for Black parents throughout U.S. history and to our present day to alert their children to the dangers inherent in encounters with white people, especially police, from whom no hope of protection or safe passage is guaranteed.

Today one can drive in minutes from the center of Port Jervis to the historic site of the village’s Black settlement, still a piney grove on a crystal reservoir north of town, but to imagine its residents walking that distance, perhaps twice a day, as they reported to and returned from domestic work in the village, speaks to a literal and substantial separation by race.

Such habitations, set apart from white residential areas and peopled by manumitted slaves and their descendants, were common elsewhere in the Lower Hudson Valley. “Skunk Hollow” was in Rockland County; the town of Chester had “Honey Pot,” later called “Guinea,” while a Black village near Harrison in Westchester County was known simply as “the Hills.” The Black population on the northern outskirts of Port Jervis was referred to as “N***** Hollow” by white Port Jervians as recently as the 1960s, long after it had been forced from its original site amid a pine and birch forest, although beginning in 1877, white town boosters and the local press, conscious of the term’s offensiveness, used the name “Reservoir View.” After 1883, when the community was forcibly relocated from its original location to an area at the top of North Orange Street, it became known as Farnumville, likely a gentle dig at the memory of Henry H. Farnum, a wealthy D&H Canal superintendent whose widow, Diana, had financed the construction of the town’s Civil War memorial and whose zeal for civic uplift was frequently, if quietly, derided.

“The town reaped little in labor from these curious suburbs,” the novelist Stephen Crane, who grew up in Port Jervis, would recall in a lightly fictionalized account, written from his perspective as a privileged white youth. “In the main the colony loafed in high spirits, and the industrious minority gained no direct honor from their fellows, unless they spent their earnings on raiment, in which case they were naturally treated with distinction. On the whole, the hardships of these people were the wind, the rain, the snow, and any other physical difficulties which they could cultivate. About twice a year the lady philanthropists … went up against them, and came away poorer in goods but rich in complacence.”

A critical juncture for the community came in 1883, when the local water utility forcibly removed 150 people from the original settlement, citing concern that “all the waste of this cesspool, whenever it rains, is carried into the reservoir and then drank by many [white residents] who do not realize what this water contains.” But the alleged “pollution” extended beyond concern for drinking water safety to what many white Port Jervians perceived as the encampment’s immorality and shantytown-like poverty. “This resort of the negroes and the very low whites is becoming notoriously bad,” the Gazette complained.

The Hollow eventually met the judgment suffered by other African American settlements in New York, including Seneca Village, the Black town uprooted from Manhattan’s west side in the 1850s to make way for the building of Central Park. Deemed by whites to be unhygienic, or simply in the way, the Hollow was declared uninhabitable and ordered cleared. When the forced exodus commenced in October 1883, the paper offered half-hearted condolences: “There is weeping and wailing in [Reservoir View] today … [It] was where many of their children were born and raised, where many a wedding took place, where many a festive night was spent, and where many [an inhabitant] closely followed by officers of the law, found a safe retreat.”

In summer 1892, a full decade after relocating the Black settlement to an area at the end of North Orange Street, thus safeguarding the town’s drinking water, white Port Jervis could look ahead to bettering circumstances. The national financial crisis known as the Panic of 1893 was still nine months away, and for now the town’s diverse industry was creating decent wages and supporting commerce. Architects came from New York City and Philadelphia to design large homes along the village’s treed avenues. From Point Peter, a noted sightseeing peak high above town (once visited and praised by Washington Irving), one could gaze out on what might be a panorama of burgeoning America—intersecting rivers and nearby mountains framing a low-rise grid of church steeples, hotels, parks, and ballfields, constituting what village promoters liked to call the “Scenic Queen of the Shawangunk Range.”

“Remote but prosperous, small-sized but grand-minded in its aspirations for modernity and sophistication,” as the scholar Jacqueline Goldsby has described it, 1890s Port Jervis “saw itself as an adjunct to the big city 65 miles away.”

The abolitionist minister and author Jonathan Townley Crane and his wife, Mary Peck Crane, had come to Port Jervis from New Jersey in 1878, when he was appointed minister of the Drew Methodist Church on Orange Square. They lost little time in establishing themselves as spiritual and reform leaders, devoted to religious as well as industrial education, temperance, and efforts to improve the lives of Black residents. Of the family’s fourteen children (nine of whom survived into adulthood), several would become fixtures in local affairs: Agnes, a teacher; William, a lawyer and civic leader who had served one year as a special judge for Orange County and was thereafter known as Judge Crane; Edmund and Luther, who both held positions with the railroad; and the youngest, Stephen, who was born in 1871 and would attain worldwide fame in the mid-1890s upon the publication of his Civil War novel The Red Badge of Courage.

(Collection of the Minisink Valley Historical Society)

The Reverend Crane wrote extensively on temperance and the evils of frivolity, especially dancing. “Young lady,” he warned in one treatise, “by imbibing a love for the dance, you will almost necessarily acquire a distaste for the duties of everyday life. The dancing master is the Devil’s drill sergeant.” Temperance was an especial cause in Port Jervis, with its dozens of saloons serving railroad workers and travelers, and Mary Peck Crane was an ardent foot soldier in the movement, fighting liquor sales with prayers and petitions urging young men to keep their bodies a fit temple for their souls. The Reverend Crane’s book Arts of Intoxication was hailed nationally as a cautionary work on the subject.

The elder Cranes also set out at once to address the village’s racial inequities, especially as they impacted education. Their Drew Mission Sunday School, open to all, eventually attracted forty-eight Black adult students and twenty-one children, with a sizable number attending the school’s first-anniversary party on May 30, 1879. The Reverend Crane, who like many white reformers had an unrealistic and overly optimistic impression of the cause he wished to serve, stressed to Black parents that education for their children must be secured at all costs, as “only by industry, sobriety, economy and piety, [can] the people of any race rise from an inferior to a higher position.”

Mary Peck Crane helped found an industrial school for Black women, with the dual aim of compensating for their lack of schooling and teaching useful household skills. To enable participation, the classes were often held in Reservoir View, with local teamsters contributing wagon transport for the white instructors and their equipment. To the African American residents, a caravan of determined white ladies bouncing over a final hill, their wagons laden with sewing machines and mounds of fabric, must have been a memorable sight. The finished clothes and shoes produced by this endeavor were given at no cost to the residents, with the suggestion that they wear them to Sunday school.

The Cranes’ anti-liquor fervor was far from trivial. Temperance was arguably the leading American reform movement of the final decades of the nineteenth century, along with labor organizing and the effort to alleviate the suffering of the urban poor. Under the national guidance of Frances E. Willard, the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, founded in 1873, built a large membership confident in the superior character of women and their essential role in the salvation of mankind. In so well-watered a locale as Port Jervis, the crusade had special resonance, particularly in the capable hands of Mary Peck Crane and her husband. It was the temperance crusaders of Port Jervis who established a reading room in the Farnum Building and campaigned successfully to bring a Carnegie library to the village, in the hope that books would offer an alternative to drink.

As a small boy, Stephen sometimes accompanied the Reverend Crane on buggy rides to minister to hardship cases. “Once we got mixed up in an Irish funeral near a place named Slate Hill,” he later recalled. “Everybody was drunk and father was scandalized. He was so simple and good that I often think he didn’t know much of anything about humanity.” Neither William Crane, the jurist, nor his younger brother Stephen, the author, would adopt their parents’ religiosity, straitlaced causes, or methods of reform. But as sons of Port Jervis, they were called upon to respond to the community’s supreme moral crisis, the lynching of Robert Lewis, parsing right from wrong and restoring meaning to ideals of justice and tolerance. Each would have an outsize role in reckoning with the event’s legacy.