FOUR “I AM NOT THE MAN”

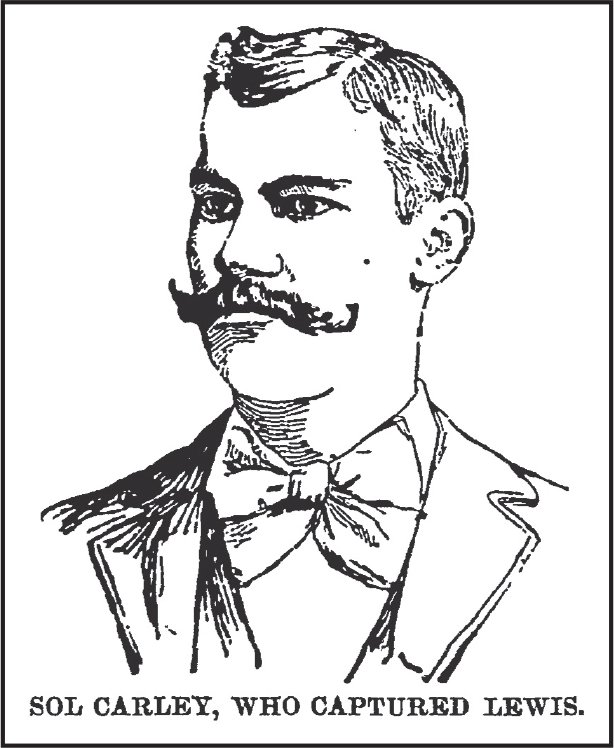

Sol Carley and John Doty left Gilbert’s Store together and headed on foot in the direction of the canal, which was only a few blocks from Kingston Avenue. Along the way, they encountered and enlisted the help of two friends, Seward “Duke” Horton, a house painter, and Walter Coleman, a confectioner, who were in Horton’s horse-drawn wagon. After they’d ridden a considerable distance, Carley asked Coleman and Horton to drive on to the village of Huguenot by road in order to cut off a possible escape route, while he and Doty walked along the towpath in the hope of overtaking Robert Lewis.

They soon caught sight of him, although to their surprise, rather than hurrying along the path, Lewis was hitching a ride on a slow-moving coal barge. At five feet seven and 170 pounds, he was a powerfully built man, and caution would be needed to safely apprehend him, particularly as Clarence McKetchnie had reported he was armed. The white men walked alongside the barge, chatting amiably with Lewis so as not to startle him into flight. After several minutes, they, too, climbed aboard.

The Black man’s decision to flee Port Jervis by canal boat, if that was what he was doing, and the fact that he did not spring to his feet and immediately run from the white men, sits rather incongruously with the allegation made against him, as did the fact that he had with him the same gear he’d been toting earlier in the day—a minnow pail, a lantern, and a reel of wire for making setlines, often used to hook catfish. He also knew Carley well enough to associate him with Lena’s Kingston Avenue neighborhood, and perhaps to suspect why he and Doty had appeared on the towpath. Either he had not committed a sexual assault on a white woman and was just a simple fisherman with his bucket and tackle, or he was displaying remarkable sangfroid.

Lewis asked Carley, the amateur baseball player, if he was on his way to a game, to which Carley shook his head and replied, “We are going to Huguenot; there is a ball there tonight and I intend to shake my foot.” Lewis, in turn, related that he was headed to Port Clinton to spend the night fishing, and that in the coming days he wanted to visit his mother in Paterson and go to New York to see if he could hire on to an ocean freighter.

Carley had no way of knowing if the man with whom he was conversing had a gun; though McKetchnie had said that Lewis had threatened him with one, the fact that the boy hadn’t actually seen a weapon would have suggested to Carley that the Black man had been bluffing. Carley focused on relieving Lewis of the knives he would be certain to have in his fishing gear. He mentioned casually that he had something stuck between his teeth and asked Lewis if he had a knife he could use to whittle a toothpick. Lewis handed over a pocketknife, but Carley tried it and said it was too dull and asked if Lewis had another. He hesitated a moment, then reached into his tackle and produced a sharper knife.

Carley then rose suddenly and said, “Bob, we’ll have to take you in.” Lewis jumped to his feet but was restrained by the two white men, as Carley gestured to the boat’s driver to pull it to shore. Ascertaining that Lewis did not, after all, have a gun, they tied his hands and marched him to the road, where they found Horton and Coleman. The whites lashed Lewis’s feet together and made him lie down on the floor of Horton’s wagon behind the driver’s bench, where he would not be easily discovered. Subsequent testimony would reveal that Carley and others in his posse, as well as a captive Lewis, understood the urgency of getting him into the hands of the law as soon as possible, before, as Lewis himself warned his captors, “a gang gets around.”

By now, word that a Black man had assaulted a white woman in Port Jervis had reached Huguenot, and a small crowd of men gathered menacingly around the wagon. Nervously eyeing them, Carley urged Horton to leave at once. With a click of the reins, the wagon shot forward, a few startled citizens jogging along after it, demanding it halt while abusing Lewis with curses.

Carley and the others later told of an unusual conversation with their prisoner. By his account, Carley asked Lewis if he had assaulted Lena; Lewis confessed that he had, but swore that the white man, Foley, had urged him to commit the act. Lewis said he had been going to the river to fish when he ran into Foley, who told him where Lena was sitting, and said, “It’s all right, go down and do it. She’ll do it.” Duke Horton remembered the directive attributed by Lewis to Foley as being more sinister, that “Foley told him that if he wanted ‘a piece’ to go down and get it … she would ‘kick a little but never mind that.’” After a pause, Lewis allegedly confided to the men in the wagon, “My God, what a mess Foley has got me into.”

Later told of these remarks, Foley vehemently denied them, insisting that he had no more than a nodding acquaintance with Lewis, having seen him a couple of times at the pool hall, and that he had not seen or spoken with him that day. If the boy Will Miller’s story is to be believed, it is possible that Lewis learned from the group at the Monticello Depot, and not from Foley, that Lena was alone by the river. But Foley’s claim that he barely knew Lewis is questionable. He had lived at the Delaware House for several months while Lewis was employed there, and they had both been banished from the place at about the same time. George Lea would later vow that the two men did in fact know each other.

Having confessed his crime to Carley and the others in the wagon, Lewis then allegedly made an unexpected suggestion: if he were only allowed to “see Johnny” (Lena’s father, John McMahon), or if Carley would do so on his behalf, the whole matter might be cleared up. In the context of the day’s events, this was a startling offer, not only for the degree of familiarity it implied existed between Robert Lewis and John McMahon, but more significantly for Lewis’s faith that a report of a violent sexual assault by a Black man against a white woman, one that ended with her bleeding and screaming for help, could be explained in reasonable terms to anyone, let alone her father, and by the very man suspected of the act.

Many of the questions that would come to haunt the story of the lynching of Robert Lewis, and befuddle those trying to understand it, hinge on these several unusual statements by the accused, attributed to him by white men who had him bound hand and foot in the bottom of a wagon. Lewis’s confession to accusations of the worst transgression a Black man could commit was novel in its implication that a white man had been the true instigator. It made the relationship between Lewis and Foley as central to the story as the encounter between Lewis and Lena, and would ultimately raise the question of whether a Black person might be excused for a crime a white man had instructed him to commit. If Lewis is to be believed, or rather, his captors’ account of his confession, there seems a strong likelihood that a relationship existed among Lena, Lewis, and Foley; one that, at least in Lewis’s mind, was more innocent than it appeared—if only he’d be given a chance to explain it.

While Carley was pursuing Lewis, authorities in Port Jervis had been telegraphing and telephoning the description of a light-skinned Black man to nearby towns, and members of the village’s police force had been dispatched to check out various local leads. A break finally came when authorities at Otisville, thirteen miles northeast of Port Jervis, sent word they had arrested someone fitting the description and had put him aboard the Orange County Express under guard to be brought to Port Jervis. White men drawn from the rail yards and the stores and saloons along Front Street quickly gathered between the railroad and the city lockup on Ball Street, just off Sussex. The suspect, Charles Mahan of Middletown, would likely have been mobbed at once had he been delivered there, but Benjamin Ryall, the general manager of the Monticello railroad, ordered the Express to make an unscheduled stop at Carpenter’s Point. There, Ryall personally escorted Mahan from the train and installed him in a room at Drake’s Hotel.

The actions of Ryall in intercepting Charles Mahan and of Carley in hurrying Robert Lewis swiftly away from Huguenot suggest that both white men were alert to the risk of a lynching. Surely they both knew intuitively that an accusation that a Black man had outraged a white woman would arouse great indignation among whites, but that awareness had been charged in recent years by the almost daily news reports emanating from the South of lynching carried out in response to such allegations. They may even have noticed recently in local newspapers that two days before, May 31, had been proclaimed the “Colored People’s Day of Prayer,” a national day of fasting and reverential protest of this most egregious form of racial violence, with endorsements from dignitaries including New York governor Roswell P. Flower and U.S. president Benjamin Harrison.

As Horton’s wagon bearing Lewis approached the outskirts of Port Jervis, Carley asked Doty and Coleman to run ahead and discreetly warn village authorities that they had the man everyone was looking for, and to prepare to get him quickly and safely behind bars. They found Officer Patrick Salley standing in front of Cohen’s Dry Goods at the corner of Sussex and Front and confided to him that they would be delivering the suspect in the McMahon case to the jail in about ten minutes, and to prepare. Salley, only six weeks on the job, nodded and, making no reply, hurried away.

By the end of the nineteenth century, most major U.S. cities had large, publicly funded police forces. The New York City Police Department, though burdened with its share of corruption, was nonetheless a leader in modernizing efforts aimed at improving crime detection and the interrogation of suspects. It also broke up prostitution rings, used mounted cops to harass workers’ gatherings, struggled to disentangle the secretive plots of the Italian Black Hand, and battled the city’s numerous street gangs. One police inspector, Alexander “Clubber” Williams, earned his legendary nickname for his novel method of clearing a neighborhood of suspected gang members by bludgeoning them preemptively, before they’d had a chance to commit a crime.

By and large, Black people were viewed unjustly by the law as second-class citizens, habitually inclined to crime and immorality. Such attitudes had been enshrined in some of the country’s first police forces, such as the Charleston City Watch and Guard, formed in the 1790s to control the enslaved population in the busy Southern port. Many historians of law enforcement in the United States draw a direct line from the modern police to the antebellum slave patrollers who regulated Black lives on Southern plantations.

Port Jervis, where Irish Americans were prevalent in the police ranks, was not immune to such prejudices. The Irish had been the largest group of immigrants to enter the Northeast beginning in the 1840s, at which time they and free African Americans were forced to compete for housing and low-skilled jobs, and the new arrivals had come of age with an inherent resentment of draconian English laws and a respect for the use of violence to combat authority and settle scores. Only a day’s train ride distant were the anthracite fields of Pennsylvania, where in the 1870s a band of Irish American vigilantes, the Molly Maguires, waged a guerrilla war of terror and assassination against the bosses of mine and railroad. Many coal-mine-region Irish in the 1860s had been draft resisters, refusing military service in protest of the fact that too many of their countrymen had been conscripted to fight, and die, in “the Negro’s War.”

Of course, in contrast to a big city like New York, the village on the Delaware presented a relatively placid scene, and the Port Jervis constabulary were relatively few in number. They were occasionally given the unpleasant chore of fishing the remains of someone ignorant of the Delaware’s strong current out of the river, but their work chiefly consisted of keeping the peace, scolding misbehaving drunks, and watching for petty acts of theft or vandalism.

Tramps—itinerant, jobless, hungry—were a notorious social problem of the age, the bane of many rural American communities for their neediness and suspected criminality; because they often moved along rail lines they were an especial threat to Port Jervis. A sentimental image has survived of a hungry tramp stealing a freshly made pie left cooling on a farmhouse windowsill, but their presence was viewed as an annoyance and a civic burden. If there was a distinction in the minds of local cops between harmless and harmful characters, it likely had less to do with who was Black or white and more to do with who was unfamiliar, homeless, and without local connection—a tramp.

No doubt a cop might be inclined to bring his baton down on a Black head quicker than a white one, for it’s probable he viewed Black people much as the local press did, with a mix of patronage and suspicion. A survey of local newspapers of the period, however, which tended to unsparingly scrutinize police conduct, fails to show evidence of a pattern of Black people disappearing into the local jail or emerging with wounds sustained in police custody. Of course, it’s conceivable there is no mention of police brutality toward Black people not because it was rare, but because it was too common to warrant mentioning.

If there was an inevitable weakness in Port Jervis’s approach to law enforcement, it was its relaxed approach to police hiring. Turnover on the force was frequent, and in a community with substantial Irish and German constituencies, many officers owed their hiring to political or ethnic allegiances. Not that there was an abundance of qualified candidates. With few exceptions new recruits had no prior experience wearing a badge, the work was relatively easy, and many were moonlighting for the extra few dollars per week. Most chiefs of police in the 1890s had other primary occupations: Thad Mead was a dentist, Dave McCombs was a butcher, Abram Kirkman worked in the railroad machine shops, and Simon Yaple was a blacksmith.

The lack of professionalism was often apparent even among local law enforcement’s best. Officer Yaple had once literally fallen down on the job in a disturbance on May 17, 1890, when, intoxicated in the middle of the day, he began harassing shop owners up and down Front Street for a drink or money to buy one. Chief McCombs hurried to the scene, but when he tried to quiet his subordinate, Yaple cursed at him and shoved him violently aside. With help, McCombs finally got his officer under control and convinced him to come along peacefully, although the village president, Obadiah Howell, confiscated Yaple’s badge temporarily and suspended him. “Such an outrageous violation of decency, law and decorum as the one described cannot be tolerated in a public officer, without bringing the administration of the law into contempt,” observed the Tri-States Union, although the paper did note that, aside from this incident, Yaple enjoyed a good reputation.

Two months later it was McCombs’s turn to be chastised, after he unjustly pummeled a German American man who had repeatedly demanded, in broken English, to know why he was being arrested. In THE COWARDLY CLUBBING CASE, the Gazette warned, “McCombs has an evil temper which exceeds his power of control,” and in words anticipating the town’s moral failure at the time of the Lewis lynching, counseled: “Both McCombs and the German should receive perfect justice under the law. It is due to law and order and to the peace and welfare of the community that justice should be impartially meted out. If there be any deviations from public duty and justice, they will be quickly detected and denounced by the press and people of the village.”

The perception of police laxity, and the reassuring likelihood that the cop one encountered on the streets of Port Jervis was your neighbor, friend, or cousin, could in turn inspire white citizens to brazenly defy the law. This weakness was exposed in a chaotic episode later that year involving two policemen, E. G. Loreaux and Patrick “Patsy” Collier, the latter of whom was off duty. On December 28, 1890, a former Port Jervis saloon owner named James Atkins was holding court at the Fowler House, a four-story hotel on Jersey Avenue. Atkins had lost his business in Port Jervis several months before on suspicion of maintaining a brothel and had moved across the state line to New Jersey. He had also recently been named as a defendant in a civil suit, and because police were prohibited from serving civil warrants on the sabbath, he dared return only on Sundays to fraternize with his Port Jervis friends. However, Officer Loreaux arrived to announce he’d come to arrest Atkins on an outstanding criminal warrant, which, unlike a civil warrant, was enforceable seven days a week. It involved a complaint from a man named Louis Schick, who said his son had been bilked in a gambling racket at Atkins’s saloon.

Loreaux was a capable officer (his arrest of two violent tramps the previous summer had been written up in the local papers), but at the Fowler House his adversary was backed by a large group of rough-looking associates. Realizing he wouldn’t be able to take Atkins without help, Loreaux called on some bystanders to assist, including his colleague in blue, the off-duty Collier. Instead of honoring the request, Patsy sent word to his brother Billy, who ran a livery stable and undertaking establishment, to quickly bring around a horse-drawn sleigh to enable Atkins’s escape. As the sleigh, driven by Billy, heaved into view, Atkins bolted out a side door and began running along Front Street toward the bridge leading to the state line, with Loreaux in pursuit. Collier was in the street too, not assisting his fellow officer but directing his brother how best to aid Atkins’s getaway. Loreaux, unable to catch up with the sleigh, drew his gun and took aim at the fugitive, but the weapon jammed and wouldn’t fire, and he was left to watch helplessly as the sleigh whipped around the corner, carrying Atkins safely across the state line. The entire drama was witnessed by Atkins’s amused cohort from the porch of the Fowler House, where they’d gathered, drinks in hand, to cheer his dash for freedom.

“A disgraceful farce,” the Union judged it, “one of the saddest commentaries that it has ever been our duty to record against the people of Port Jervis.” The idea of saloon riffraff doubled over with laughter at the plight of a lone policeman trying to enforce the law was an uncomfortable reminder of the town’s perpetual struggle to contain the vice and immorality of its rougher elements. “Who from other parts will care to visit us, or to make this town their home?” the paper asked. “The whole town is responsible. The openhanded mob sway Sunday was worthy of a town in the wild West, and it cannot be looked on with indifference by a town that has the pretensions of civilized life.”

An official inquest into the lynching of Robert Lewis would ascertain not only that Officer Patrick Salley failed to act on the warning he’d received from John Doty and Walter Coleman but also that he was little more than a spectator to the disaster that ensued. One of only eight officers who composed the Port Jervis police force, Salley was a part-time “special” or auxiliary officer; at this critical moment some of his colleagues had been dispatched to deal with other leads connected to the assault on Lena McMahon, and with his nonparticipation, this left only three officers to get Robert Lewis into the Port Jervis jail in one piece—Simon Yaple, William Bonar, and Ed Carrigan. This task was made more challenging by the fact that the jail, surrounded by other structures, tucked behind a fire hose station, and likely windowless, offered no direct access on either Bank or Sussex Streets but was reachable only via a narrow alleyway. With the continued swelling of the crowd, the trio of policemen was outnumbered by at least a hundred to one, and nothing in their experience had prepared them for so intense a crisis of crowd management and riot control. Even the batons they were issued were shorter than those used by their big-city counterparts, which could if necessary be held crosswise in both hands and used to push back against throngs of strikers or protesters.

As Duke Horton later testified, a pack of men fell in behind and surrounded his wagon the moment it stopped before the jail. Climbing down from the buckboard, Horton recalled, “I couldn’t get to my horse, the crowd was so thick.” According to an account in a Poughkeepsie paper:

Every man in that crowd was for a time nothing more than a mad man, made insane by the thirst for the blood of the Negro who had so brutally assaulted one of the best girls in the place, a girl loved by everybody.

When the Negro arrived, the pent-up fury vented itself in one long, loud howl, and a wild break was made for the wagon. Lewis looked for a moment about him, arose and tried to jump. A hundred men stood like so many panthers, ready for him.

Yaple, whose walking beat had taken him regularly by the Delaware House and who was acquainted with Robert Lewis, now heard his beseeching words: “Officer, lock me up. They’re tearing my clothes off. I am not the man.” Yaple tried to keep the prisoner from being pulled away, but his efforts and those of his colleagues Bonar and Carrigan were useless. The police became, the New York Sun reported, “like children in the hands of the mob … A dozen times Yaple was thrown to his knees, and once down on his side.” When he tried to strike back at his assailants, he found the crowd so dense he could not raise his club.

In the melee, neighbor confronted neighbor. William T. Doty, editor of the Orange County Farmer, claimed he saw the hotelier James Monaghan urging the mob on. When Doty scolded Monaghan that he “should be in a better business,” Monaghan turned, his face unrecognizable with rage. “Keep your goddam n****** off the street, then!”

Exhilarated at having wrested control of the accused from the police, the mob began pushing and dragging Lewis up Sussex Street. “Gentlemen, you have the wrong man,” Lewis pleaded. “I didn’t do it. I am the wrong man.” In reply came the vilest obscenities, along with the exhortations: “Lynch him!” “Hang him!” “Kill him!” “String him up!” The intensity of the physical assault on the captive was shocking in its violence—a blinding flurry of blows and kicks and the slashing with knives of Lewis’s clothes and ultimately his flesh.

Lewis’s plea to be brought inside the jail had been his appeal for due process of law; his statement “I am the wrong man,” his desperate cry of innocence. But the witness Dr. Halsey Hunt recalled, “No one really listened. You might as well have talked to the ocean.”

The police were still reeling from the shock of forfeiting their prisoner when a rope appeared, likely from a nearby business, and within seconds was slipped over Lewis’s head. The sight emboldened Yaple and Bonar, who with renewed effort pushed back against the onslaught. Yet as often as they pulled the noose off Lewis’s head, as many times the mob replaced it, and in turn tossed it mockingly over the heads of the officers. Several other policemen now arrived, but there was little they could do. They either withdrew or allowed themselves to be shoved to the fringes of the crowd. Even the former police chief Dave McCombs appeared uncharacteristically passive; several witnesses, including Yaple, looked to him for assistance but did not see him in any way resist the lynching. Patrick Collier, reinstated to the force after having been fired over the James Atkins fiasco two years earlier, was again seen seriously shirking his duties, even siding with the mob.

The village president, Obadiah Howell, tried to restore order. An attorney known for defending the legal rights of children and incompetents, and, as a special judge, for upbraiding poorly prepared lawyers, now let loose his temper on the police. He fired one officer, William H. Altemeyer, on the spot. Then, seeing the mob tie the rope that was looped around Lewis’s neck to an electric light pole, he cut it down with a pocketknife and ran with it to the closest store, where he ordered the proprietor to hide it. The crowd howled with outrage at the interference.

Yaple later said that he recognized several faces in the group—John Kinsella, a railroad engineer who had been in the news himself two months earlier when his westbound milk train 17 struck and killed a man walking on the tracks; the Front Street grocer John B. Eagan; and the depot worker John Henley, who kept insisting, “Shoot Yaple! Get Yaple out of the way!” One man present—possibly Henley—was speaking through a tube hidden by a kerchief around his throat, apparently as the result of an operation, and his croaking, mechanically altered utterances added greatly to the sense of disorder.

The prisoner, when possible, appealed to people he knew in the crowd. Recognizing Dr. Hunt, he implored him to save his life, and the physician briefly joined President Howell in trying to convince others to stop and allow the law to take its course. Others were also urging calm—the Reverend William Hudnut of the Presbyterian Church; Volkert V. Van Patten, a Civil War veteran who ran a local tailoring business; and Ben Ryall, the railroad manager—but all were cursed at and warned away. A reporter saw Chief Abram Kirkman being “roughly handled by some of the ruffians, a minister of the Gospel [Hudnut] struck with a stick,” and several other notable citizens assaulted. Howell was surrounded by a group of red-faced men who shoved and screeched at him, then, for added insult and emphasis, yanked his hat down over his eyes. As the crowd advanced up Sussex Hill toward Main, sending up cries and catcalls, it paused momentarily beneath every electric streetlight, ironically the very symbol of Port Jervis’s most progressive aspirations, weighing whether it was suitably sturdy to support a hanging.

The crowd meanwhile grew in size and length. Sussex Street was a commercial and residential artery that climbed a substantial hill, and the press of bodies ascending this narrow passage, with the loud exhortations of the crowd and the victim’s shrill cries of pain and protest, would have created an unimaginable din and commotion.

Lewis continued to protest that he was “the wrong man,” but his fate only grew more perilous when, as the mob made the right turn from Sussex onto Main, Clarence McKetchnie appeared, the boy who had confronted Lewis on the riverbank. “This is the right man, Mr. Ryall,” McKetchnie announced. “I saw him commit the act.” The Reverend Hudnut, for one, was unconvinced. “The mob had no proof of the victim’s guilt,” he would later say. “There was merely the evidence of one man [Sol Carley] who said that the negro had confessed, and of one small boy, a boy so bad that at 12 years of age he is beyond his parents’ control, who cried ‘that is the man!’” But Hudnut understood the multitude was by now deaf to any information of a potentially exonerating nature. “Port Jervis people say a regiment of soldiers could not have stopped the mob,” the Gazette would comment.

Lynch mobs had their own hierarchies of participation. One could be both present and yet at a considerable remove from what was happening. As the throng moved and surged, a person might find it hard to maintain his footing, let alone a clear view of what was taking place. The merely curious, hovering at the edge of the crowd, craning for a view, had to be content with speculating about what was occurring at the center. Those closer in might shout insults or encouragement or dart in opportunistically to verbally or physically torment the captive. The leaders tended to be individuals who held some special grudge against the victim or, more likely, were men who took pride in exhibiting their physical strength and powers of intimidation. Intoxicated, if not by liquor then by their own sudden importance, having banished all possibility of retreat, these figures now guided the whole in a loose yet determined improvisation, heading toward some dimly perceived objective—a tree, a fence, a field—where the mob’s work would become final.

Officer Bonar suddenly offered an inspired suggestion. Citing a feature common to some Southern lynchings, he proposed that Lena McMahon be allowed to see and positively identify her attacker. President Howell, recognizing its potential as a stalling tactic, endorsed the idea at once, as did others nearby, but rather to savor its potential melodrama. “Take him to see the girl!” someone shouted, to broad assent, and the crowd moved forward with this new purpose in mind.

Such encounters belonged to the grotesque theatrics of Southern lynchings known as lynchcraft, the aesthetic by which the “performance” of a summary execution, and the conduct of its participants, were judged. “Lynchcraft” might refer to rituals such as bringing an assault victim face-to-face with her alleged attacker or having her “sentence” him to his fate. These feeble simulations of due process might make for gripping theater but had little to do with ascertaining innocence or guilt. Only a few months before, on February 20 in Texarkana, Arkansas, a Black man named Edward Coy had been lynched before a thousand onlookers after his affair with a white woman named Julia Jewell was made public. Coy, moments before his immolation, had asked plaintively of Julia, who was given the “honor” of setting the pyre alight, “How can you burn me after we’ve been sweet-hearting for so long?”

Of course, these measures were also understood to potentially retraumatize women in Lena McMahon’s position, forcing them to relive the original outrage they’d suffered as well as to become complicit in condemning the lynching victim to a horrific death. The view that the female victim of an assault should at all costs be spared meeting her “ravisher” was a concern invoked frequently as a rationale for lynching itself, since hurrying an alleged assailant to his death eliminated the possibility a vanquished woman would ever be made to sit opposite him in open court, or be questioned and cross-examined about what she’d endured.

Grateful for the delay Bonar’s idea had won, Howell went by a back route to the McMahons’ house on West Street to ask that, in order to avoid further violence, Lena not identify Robert Lewis as her attacker, even if he was in fact the man she thought responsible. The family, still huddled around their recuperating daughter, was stunned to learn a crowd of hundreds was heading toward their door, but reassured Howell not only that Lena would deny recognizing him if she saw him but also that neither she nor they considered the bus driver from the Delaware House to be the perpetrator. Lena, recovering under the gentle influence of laudanum given to her by her physician, Dr. Solomon Van Etten, maintained that she was unsure who her attacker had been, other than to say she thought he was a stranger, perhaps a tramp who’d been living in the woods.

Regardless of what reassurances Howell had obtained at West Street, the plan to carry Lewis there was short-lived, made obsolete by the arrival of the bizarre and incendiary news that Lena had already died of her wounds. The rumor was attributed to the unimpeachable authority of Dr. Van Etten—a Civil War surgeon, commander of a local war veterans’ lodge, and descendant of some of the region’s original Dutch settlers. The effect was to bring instantly from the crowd a full-throated cry for vengeance.

Van Etten would strongly denounce the notion he would be so reckless as to spread such a falsehood. At the inquest he testified that he was called to attend to Lena early in the afternoon and that later, as he walked down the street, as many as twenty people had stopped him to ask after her. He said that at City Hall he had “pictured the crime in strong terms to impress on the Chief [Abram Kirkman] the necessity of a diligent search” for the perpetrator, who was then still at large. Van Etten’s depiction of Lena’s condition, like his urgings to Kirkman, repeated by numerous others, had likely grown in force with each repetition, until one reprinted version had him saying, “If they could know what I knew and could see what I’ve seen, they would not hesitate to lynch the negro.”

Now there was no longer any call for delay. The crowd settled on a substantial maple tree at East Main near Ferguson Avenue, feet away from a house owned by Edwin G. Fowler, in view of the looming steeple of the Dutch Reformed Church. Fowler, an accomplished horticulturalist who grew fruit trees on his property (and also gave singing lessons), was likely not at home.

A rope was rigged to an upper limb and, with a gasp from onlookers, Lewis, bloody and bare-chested, was hoisted high into the sky, as if, one witness remembered, “the negro was going like a kite.” In the deep twilight his distorted features were made garishly visible by an electric streetlight, and as it was a warm evening and the town’s windows and many of its doors were wide open, his cries entered every home.

Judge William Howe Crane was in his study at 19 East Main Street, the site of some of the town’s most stately homes, when a maid entered and informed him a crowd was about to hang a Black man in the front yard. Quickly dressing and rushing across the street, the judge demanded that a path be opened for him so that he could reach the mob’s victim. Crane was formidable in appearance—some said he resembled a horned owl—and his voice and manner commanded respect. He immediately tried to assist Lewis by lowering him back down to the ground. Badly bruised and bloodied, Lewis was struggling to breathe and seemed barely conscious. Under ordinary circumstances Crane would have recognized Lewis’s face, as the bus driver was a familiar presence in lower Pike Street, where Crane had his law office. But now it was dark and the man’s features were grossly disfigured. The judge did, however, recognize several men in the crowd, including the newspaper editor William Doty, the Reverend Hudnut, Dr. Walter Illman, and the police officers Bonar, Yaple, and Collier.

“The crowd was dense in all directions,” Crane later testified. “I saw Collier do nothing except to come in and back out; I asked him if he was an officer; he said ‘not now,’ after which I lost sight of him; he did nothing I saw that was in aid of me or [Officer Yaple].” Seeing that Lewis’s whole body was quivering and that he was still alive, Crane asked Dr. Illman if he might yet be saved. Illman said yes, so long as he was taken at once to a hospital. When someone nearby informed Crane of the transgression with which Lewis was accused, the judge responded sharply that such matters must be left to the courts and that, in any case, the victim’s face was so mauled and covered with blood, it was impossible to identify him with any certainty. Crane recalled that “just then someone caught hold of me and jerked me back. I turned and saw Dr. Illman. He said ‘there is no use, Judge, we will only get hurt.’” Crane made one final try. The mob had flung the rope over the branch of the tree again and hoisted Lewis back up. Crane grabbed the rope and tried to haul it down but lost the struggle with those pulling hard from the other end. It must have been several moments later that Robert Lewis died, suspended in the air, while the crowd gaped upward from below. The gathering had by now grown to as many as two thousand people, drawn by the commotion—men for the most part, but also women, as well as adolescents like Clarence McKetchnie.

After the great din of the past two hours there came a noticeable hush, a striking absence of sound, as many stood for several minutes looking up at the result of their collective cruelty. The crowd began to stir, murmur, and move apart only when lightning flashed in the distance.

Crane returned to his house, where his family was waiting, fearful for his safety. A few minutes later came a hesitant knock on the door; Crane opened it to find Patrick Collier, wanting to know what the judge’s wishes were. The judge replied curtly that it was rather late to be asking after his wishes, but said there was nothing to do now but to cut the body down and notify the coroner.

This was done and then, with the coming of the storm, it began “raining pitchforks,” and Lewis’s body was left where it had fallen for half an hour or more, untouched, in the mud, blood gathering at the mouth. In days to come, many swore that the uncanny arrival of so merciless a storm could be no coincidence, but was, per the Tri-States Union, a visitation from Mother Nature herself, “weeping and protesting in deepest tones.” Some even feared the spirits of the valley’s long-vanquished Indigenous people had been aroused.