SIX THE VIGOROUS PEN OF IDA B. WELLS

The year Robert Lewis was lynched in the streets of Port Jervis, the major political story of the summer was the two parties’ nominating conventions and the impending presidential battle between the Republican incumbent, Benjamin Harrison, and the Democrat Grover Cleveland, a contest that reflected in part the nation’s struggle over civil rights. Republicans had tried recently to expand voting protections and education for Black people in the South; however, the country’s prevailing mood, personified by Cleveland and the Democrats, was for sectional reconciliation and a retreat from further meddling by Washington in the South’s affairs.

New York City had begun the decade with the launch of a popular campaign to finance the construction of a tomb for Ulysses S. Grant, the former general and president, who had died in 1885. It was the eve of the city’s great age of civic architecture, and New York fought hard for the right to build the memorial, a project undertaken less in honor of Grant’s military defeat of the Confederacy than in the emerging spirit of national reunion. It was in New York that Julia Grant, the president’s wife, made social calls to Varina Davis, widow of the president of the Confederacy, and General Dan Sickles reminisced with his Confederate counterpart James Longstreet about the Battle of Gettysburg, where they had met as lethal foes. Relegated to the hinterlands of compassionate inquiry among whites amid this reconciliatory jubilee was the imperative of ameliorating the remaining inequities between the races. “The Civil War ceased physically in 1865,” noted Thomas Beer, a chronicler of the Mauve Decade, which closed out the century, “and its political end may be reasonably expected about the year 3000.”

The North saw itself beset by new challenges. As of 1880, industrial workers outnumbered farmworkers for the first time in U.S. history, and with the growth of organized labor came frequent conflicts with capital and fears of “foreign” political movements (socialism, communism, anarchism) associated with agitation for working people’s rights. Chicago’s 1886 Haymarket Riot, and the subsequent trial and execution of its alleged anarchist perpetrators, had riveted the country, and in July 1892 the Homestead Strike near Pittsburgh would see murderous battles between steelworkers and their families and Carnegie Steel’s hired Pinkertons. At the same time, American cities struggled with a host of social ills, including unemployment, inadequate housing, health crises arising from overcrowding, and the lack of care for children and families.

Meanwhile, the Civil Rights Act of 1875, the “Capstone of Reconstruction”—guaranteeing equal rights in public accommodations such as hotels, restaurants, theaters, and transportation—was in 1883 gutted by the U.S. Supreme Court. A federal elections bill, put forward in 1890 by Senator Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts to safeguard Black voting rights in congressional elections, known by detractors as the Lodge Force Bill, was defeated. A similar fate met a federal education reform act sponsored by Senator Henry Blair of New Hampshire aimed at alleviating the rampant illiteracy in the South, particularly among Black children. In the former Confederacy a white conservative crusade known as Redemption proudly trampled into the dust the last vestiges of Reconstruction, as the federal government, worn down by the region’s unrelenting resistance, abandoned its commitment to facilitate and defend full citizenship for African Americans.

Even Northern conservatives argued that those in Congress who overindulged the project of Black advancement did a disservice to the very people they aimed to help, coddling them with the false guarantee that the government would see to their needs. The concern that Black Americans not become the “special favorite of the laws,” a phrase that emerged from the Supreme Court’s ruling against the Civil Rights Act of 1875, grew familiar by repeated utterance. The related notion that it was futile, under any circumstances, to attempt to adjust social inequities through legislation was promulgated by William Graham Sumner, a professor of political science at Yale, whose observation that “stateways cannot change folkways” became a useful impediment to late-century equal rights efforts. Such dogma, hypocritically, did not keep Southern legislatures from passing laws—stateways—to restrict and disincentivize the Black vote.

So pervasive was the assault on the country’s postwar idealism that in 1884, when Grover Cleveland won his first term, becoming the first Democrat to attain the White House since the war, fears arose he would seek to topple the great edifice of Reconstruction, the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments, which had granted African Americans freedom, citizenship, and the franchise, respectively. Cleveland took a dim view of Reconstruction, which he considered a failed experiment, and held that Black Americans need make their way by their own initiative, not from reliance on government largesse. He lost the next presidential contest in 1888 to Harrison, who had more enlightened views on the subject, but who was unable to see reforms like the Lodge and Blair bills through Congress, nor a proposed constitutional amendment he favored to overturn the Supreme Court’s 1883 ruling rejecting the Civil Rights Act of 1875. Now, in 1892, the two men were set for a rematch.

These political currents involving race had a lethal undertow: the conviction among many whites that Black people were perpetual outsiders, “citizens” in name only, who existed at the margins of American life and would never fully belong in it. This idea was nurtured by dubious “race science” theorists at elite universities and in the pages of the country’s leading magazines. The geology professor Nathaniel Southgate Shaler at Harvard; the zoologist Edward Drinker Cope and the linguistics professor Daniel G. Brinton, both at the University of Pennsylvania; Frederick L. Hoffman, a statistician with the Prudential Insurance Company; and Lester Ward, a professor at Brown University and the first president of the American Sociological Association, were among those who questioned the very survivability of African Americans, given their alleged lack of initiative and resourcefulness and inability to control “the lower passions.” Every Black man who raped a white woman, Ward posited, was driven by “an imperious voice of nature … to raise his race to a little higher level.”

Noxious views like these crept into American homes in the pages of The Atlantic, The Nation, and North American Review, as well as syndicated newspaper pieces and editorials. “What of the common negroes?” asked a typical feature in the Olean Herald (New York):

Well, they are like their kind everywhere else—singularly like grownup children. They are, in fact, soft children of the tropics—a race suddenly transplanted from the lowest civilization and placed under the rigid requirements of the very highest, with only a century or two of training to fit them for it … They crowd the sidewalks, perch on the fences … swagger and shove, and if there is no policeman in sight are liable to be insulting to certain classes of white people. It is, however, but the exuberance of an untrained race, in whom a century or more of slavery and a quarter of a century of freedom have still left the tropical nature pretty strong.

This humbug of racial pseudoscience was not new. It had, however, been inadvertently reinvigorated by the appearance in 1859 of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, a work often taken out of context to promote notions of the “survival of the fittest” and the alleged inferiority of African Americans, along with immigrant populations of Italians, Irish, Jews, and Chinese, as well as Indigenous peoples. One pernicious lie that would have held sway at the time of the Port Jervis lynching was that America’s formerly enslaved people had simply not made good on the generous constitutional gifts they had been given, and thus had failed to thrive in the country’s system of competition and opportunity. Such a conclusion conveniently neglected slavery’s painful emotional legacy, as well as the practical difficulties for the freed people in gaining economic and political footholds, especially in the postwar South, where they were denied land, access to capital, and, increasingly, the vote. The lawyer and social justice activist Bryan Stevenson has argued recently that this white-imposed “narrative of racial difference,” as it was amplified by nineteenth-century “experts,” has perhaps been slavery’s most harmful vestige, “the idea … that Black people are not as good as White people, that Black people are not fully human [and] are less evolved, less capable, less worthy, less deserving.”

Despite the countless obstacles strewn in their path, formerly enslaved Americans had emerged as a significant political force, particularly where their concentrated numbers enabled them to vote for Black representation. As many as two thousand African Americans served in official capacities in the Reconstruction era, from county sheriffs to tax collectors to representatives in the U.S. Congress. But the new mobility and ambition of formerly enslaved men and women, as well as of the up-and-coming younger generation who had never known that condition, posed a distinct challenge to whites, who resented deeply the reality of Blacks attaining elective and appointed office and the expectation that whites need live “beneath the splay foot of the Negro.” But nothing signaled the unwanted consequences of Black equality, or highlighted white hypocrisy, more keenly than the specter of physical relations between Black men and white women. This haunting projection of the white man’s own adulterous sin led him to place Southern white womanhood high on a pedestal of purity and unblemished virtue, and to elevate as well the defense of its inviolate honor.

Lynching in the South thus served as a means of communal acclamation, soothing perceived threats in the white mind of Black political and economic advancement, of social equality and sexual “deviance,” anxieties that were in turn compounded by young white women’s increasing departure from home and smothering parental jurisdiction to seek independence and opportunity. The cry of diminishing white male authority in this changing world found both solace and amplification with the mob—righteous in its victimhood, blameless in its anonymity.

Under such self-induced pressures, white sensitivity to Black transgression was set routinely at a hair trigger; an alleged sexual offense demanded swift retribution. But any number of actual or perceived violations of regional norms, arising from “impudence,” private disputes over wages or property, the refusal to give the right-of-way, and so on, could suffice to bring an act of lethal summary “justice.” The ChicagoTribune tabulated deaths of Black men lynched for mule stealing, slander, and threatening to make political comments; others died for “being found in a white family’s room” or for simply “being troublesome.” The New York Age wrote of a Black clergyman pummeled by a mob in Georgia because he went about in a fine suit and “shiny shoes.” As W.E.B. Du Bois would explain in his 1903 book of essays, The Souls of Black Folk, “[The South’s] police system was arranged to deal with Blacks alone, and tacitly assumed that every white man was ipso facto a member of the police. Thus, grew up a double system of justice, which erred on the white side by undue leniency and the practical immunity of red-handed criminals, and erred on the Black side by undue severity, injustice, and the lack of discrimination.” For the Black journalist Ida B. Wells, such an imbalance meant that “the unsupported word of any white person for any cause is sufficient to cause a lynching.”

On May 27, 1892, only days before Robert Lewis was lynched, President Harrison, in response to a resolution from a Black Virginia Baptist convention seeking a federal anti-lynching law, said, “[I] have asked that law-abiding men of all creeds and all colors should unite to discourage and to suppress lawlessness. Lynchings are a reproach to any community … and shame our Christian civilization.” He conceded, however, that obtaining such a law would not be easy; murder was technically a state crime, and as the defeat of both the Lodge and Blair bills had shown, Congress was unlikely to overcome the unanimous Southern rejection of federal intervention in the region’s affairs, or, for that matter, mounting Northern apathy on the subject. Much as the Grant administration had once pronounced itself weary of addressing the “autumnal outbreaks” of Southern voter intimidation and wanton violence around fall elections, so the Northern press had also grown comfortable with the idea that the South should be left to work out its own destiny.

Broader recognition of the lynching issue had been set in motion by the efforts of a handful of Black journalists and publishers, especially Ida B. Wells of the Memphis Free Speech and Headlight, and the Afro-American League, the country’s leading postwar national civil rights organization, with a decidedly activist bent. It had helped lead the call for the May 31 day of fasting and prayer to protest lynching, with public observances planned in a number of Northern cities. “The courts of justice turn a deaf ear to our cries for protection, the dog is set upon us to drink our blood for human satisfaction,” the civil rights attorney D. Augustus Straker proclaimed at a Michigan anti-lynching summit. He beseeched the heavens, “Oh, God! Wilt thou hear us?”

The petition for the May 31 Colored People’s Day of Prayer was signed by more than a hundred well-known educators, writers, and jurists, including Booker T. Washington and Frances Ellen Harper, the renowned abolitionist, poet, writer, and civil rights leader. Also among the signees was T. Thomas Fortune, the influential editor of the New York Age and a founder of the Afro-American League, and Albion W. Tourgée, a former Union soldier and North Carolina judge whose popular novel A Fool’s Errand (1879) gave an intimate, discerning account of the South’s postwar intransigence. Tourgée, who would represent the plaintiff Homer Plessy in the 1896 Supreme Court discrimination case Plessy v. Ferguson, was one of the first prominent whites to raise public alarm about lynching.

In fact, it was the mass lynching of white people in New Orleans that had helped make the subject a focus of wider concern. On March 14, 1891, at a time of growing local fears of an active criminal underground known as “mafia” (a term new to the American public), a white mob had entered New Orleans’s main jail and lynched eleven Italian Americans suspected of having conspired in the recent assassination of the chief of police, David Hennessey. Shot from ambush on a darkened street, Hennessey had whispered with his last breath a single word: “Dagoes.” This lynching of men against whom nothing had been proved (six had already been acquitted), in a place where they had no chance to flee, became an international incident when Italy, offended by the terroristic slaughter of its nationals, broke off diplomatic relations with the United States.

The threat the New Orleans massacre raised, in a year that already had seen an obscene number of lynchings of African Americans across the South, was that mob law was transportable, that it could claim white lives as well as Black and trample established law anywhere, anytime it chose. In June 1892 this peril materialized at the corner of Ferguson and Main in Port Jervis.

Afro-American League members were understandably outraged by the manifestation of Judge Lynch in New York State, not forty-eight hours after the fast day set aside as a protest against lynching. Were such gross manifestations of violent intolerance to be emulated everywhere throughout America? The league’s Newburgh chapter lost no time in decrying “the action of the angry mob upon Bob Lewis,” who was “disgracefully lynched without law or justice.” Their message concluded: “We offer our thanks to the President of the village [Obadiah Howell] for the efforts to protect the prisoner in such a perilous predicament. And we earnestly appeal to the citizens of the Empire State as American citizens to give us the protection that is due American citizens.” That same week, New York governor Roswell Flower, in attendance at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, responded to the league’s efforts and the news from Port Jervis by offering a resolution condemning lynching for inclusion in his party’s platform. It was quickly voted down by Southern delegates for its “possible implication casting some reflection on their state governments,” prompting the Black-published Freeman of Indianapolis to quip, “It used to be said that while every Democrat was not a rebel, every rebel was a Democrat. By the same rule of reasoning, why may it not be said that while every Democrat is not a lyncher, every lyncher is a Democrat?”

The situation for Black Americans that summer, in Port Jervis and elsewhere, could hardly have been more bleak. The African American historian Rayford Logan would term the post-Reconstruction decades “the nadir” of the Black experience in America, a time of rampant lynching, voter suppression, convict labor, and the ongoing deprivation of rights and property. In Mississippi in 1890 a model piece of legislation—soon known as the Mississippi Plan—pioneered novel ways to extinguish Black voting through poll taxes, literacy tests, grandfather requirements, an “understanding clause,” and myriad other forms of procedural harassment. These methods were then enacted by many neighboring states—effectively denying African Americans the franchise without appearing to violate the Fifteenth Amendment, the very trickery the reforms of the deceased but greatly mourned Lodge bill had been designed to confront.

T. Thomas Fortune was committed to jarring awake a nation grown narcotically indifferent to the extent of Black suffering. A native of the Florida Panhandle, he had been an aide to Josiah Walls, the only African American elected to Congress from the state in the nineteenth century. In 1877, with Reconstruction drawing to a close, Fortune left politics for the challenge of newspaper publishing and within a decade was editing the New York Age, destined to become one of the nation’s best-known Black publications of news and opinion. He admired Walls and the other elected figures who had risen on Reconstruction’s promise (Fortune’s father, Emanuel, had been a state politician in Florida), but many had by now been driven from public life, by both assaults on the Black franchise and the frequent and wrongful stereotyping of Black officials as incompetent and corrupt. Like Frederick Douglass, Fortune believed it vital to defend Black people’s hard-won constitutional rights to equality and citizenship and conceived of a national advocacy organization as the best way to safeguard them. Protecting the vote was a priority, but the agenda of Fortune’s Afro-American League, whose first branch was founded in Richmond in June 1887, took on multiple challenges, including school segregation, lynch law, and the denial of equal access to public accommodations.

“See here, young fellow,” Fortune, in one exemplary protest, told a bartender at New York’s Trainor’s Hotel who refused to serve him because of his race, “you will fill my order, and if you do not, I will remain here and ornament your establishment until you close in the morning.” Fortune was arrested but, with the aid of the attorney McCants Stewart, sued the hotel for damages. “Let us agitate! Agitate! AGITATE!” Fortune urged his readers. “Until the protest shall wake the nation from its indifference.”

In the Negro Convention Movement, begun in Philadelphia in 1830 and active until the Civil War, free Black men and women—religious leaders, educators, artisans, joined by those in flight from enslavement—met in state, regional, and national gatherings to address issues of discrimination, white violence, abolition, and African American emigration. Useful in fostering solidarity, the conclaves, however, often led to little more than well-drafted resolutions. Fortune insisted his league would be an activist organization, one that would make demands, not simply agree on shared sentiments. He believed that whites were capable of changing their behavior and attitude toward people of darker skin, because “the heart of the nation is true to the sublime principle of justice,” and would respond to advocacy that demonstrated the clear legitimacy of Black citizenship.

The league’s hopes were raised when Benjamin Harrison won the 1888 election, although even with Republican control of the White House and both houses of Congress, the South maintained a powerful emotional edge. With the region’s history of noncooperation, Klan violence, ballot box fraud, insistence that it alone “knew the Negro,” and banner-waving legions of the Southern Redemption (for all its pomp and pageantry, more or less the white mob, now led by ex-Confederate dignitaries), the South’s obstinance ultimately broke down the North’s will to endlessly readjudicate the Civil War. Henry W. Grady, the Atlanta Constitution editor, in 1886 announced a “New South,” one open to an influx of Northern business capital and with its “colored problem” sufficiently under control, a boast of Southern progress that Fortune swiftly punctured by noting how cruel and violently racist the New South remained, even a quarter century after Appomattox. When Grady in turn dismissed Fortune as an “Afro-American agitator,” Fortune warned the editor, and assured his own readers, that the ubiquitous Afro-American was indeed an agitator, one who would sound “the death knell of the shuffling, cringing creature in black who for two centuries and a half had given the right of way to white men.” In his place, Fortune hailed the coming not of a “New South,” but rather of “a new man in black, a freeman every inch, standing erect and undaunted, an American from head to foot … who looks like a man!… and bears no resemblance to a slave, a coward, or an ignoramus.” Shooing away white detractors like Grady as so many “croaking ravens,” Fortune assured his followers: “No race ever had before in the history of mankind greater cause for organization, for self-reliance, for self-help than Afro-Americans.”

Fortune’s militance impressed other leading Black publishers and journalists, among them Wells at the Memphis Free Speech and Headlight, William Calvin Chase at the Washington Bee, and John Mitchell, Jr., of the Richmond Planet. Horrified by the South’s brutality and indifference and Washington’s failure to act, they saw with Fortune the critical need for bold words and effective action. The end of the Civil War and the opening of the vast theater of Reconstruction across the South, with its four million emancipated freedmen, had for many years soaked up what attention reformers and the nation paid the advance of equal rights. The Afro-American League thus represented for many Black activists a return to the prewar intensity of the abolition movement and the resistance to the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, when the cause of liberation was national, and centered in Northern cities. Wells called the league “the grandest [idea] ever originated by colored men,” as she admonished the Black America she so dearly loved to fight now or be “stigmatized forever as a race of cowards.” By fall 1889, more than forty state and local chapters had formed.

The league saw one opening in creating legal precedents for its agenda by challenging racial discrimination in the North, common injustices such as prejudicial insurance rates for Black people and restaurants and hotels that illegally denied them service. While the success rate was modest, publicized cases of this kind, simply by being aired in the white and Black press, advanced the perception that such clearly obvious claims for basic racial equity were completely deserving. This work inspired several like-minded campaigns, including one in response to the lynching at Port Jervis.

“Whatever Bob Lewis’s own crime, the community’s was murder,” declared the attorney Rufus L. Perry, Jr., of Brooklyn, leader of the Friends of Bob Lewis. In summer 1892, the group announced the first lawsuit of its kind in New York, seeking twenty thousand dollars in damages from the state on behalf of Lewis’s mother, citing criminal negligence in his death. A graduate of the New York University School of Law, Perry, from his offices on Fulton Street, was already making a name for himself as Brooklyn’s “Negro lawyer.” His father, the Reverend Rufus Perry, was an influential community leader as head of a large Baptist congregation in the borough. The younger Perry’s closest associates in the Lewis case were Dr. Robert R. Meredith, leader of the Tompkins Avenue Congregationalist Church in Brooklyn, and Louis Stoiber, an attorney and early advocate for the Legal Aid Society, which was founded in New York City in 1876 to assist indigent German immigrants.

Perry, Meredith, and Stoiber saw the Port Jervis lawsuit as the beginnings of what they hoped would become a permanent legal advocacy group capable of holding communities accountable for lynching. If mobs went unpunished in criminal court, as so often happened, towns and states could at least be brought to heel by court-sanctioned demands for financial restitution, a process that would at the same time publicly shame officials’ abhorrent failure to protect a citizen’s right to the presumption of innocence. Using a similar dynamic, some of the first state anti-lynching laws enacted in the early twentieth century would reach over the heads of the mob entirely, placing legal culpability at the doorstep of any sheriff who did not use the power of his office to deter an act of summary justice. In the context of Perry’s lawsuit, Port Jervis’s botched effort to safeguard the life of Robert Lewis seemed an open-and-shut case. As the New York Herald had scolded a few days after the lynching: “Four New York policemen could have prevented the mob on Thursday night from murdering Lewis, and one or two New York detectives would have before this caught several [of those responsible] and locked them up. Not a step has been taken to secure the arrest of the ringleaders. Not even a reward has been offered for the identification and arrest of any of the lynchers.” Although a judge might sympathize with the Port Jervis police on account of the lynching’s spontaneous nature and the overwhelming numbers unprepared law officers found arrayed against them, it seemed nonetheless a straightforward matter to conclude that local authorities had failed Robert Lewis.

It is unclear, however, whether the legal papers of the Perry group were ever served on Governor Flower. As the Tri-States Union pointed out, although a state statute of 1855 made counties and municipalities potentially liable for property damage caused by a mob, there was no corresponding fiscal remedy for loss of life, and a legal principle known as the doctrine of sovereign immunity tended to protect states from lawsuits involving violations of an individual’s constitutional rights, such as the right to due process. The protection had been reaffirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court as recently as 1890, in Hans v. Louisiana. The upstate press took interested note of the innovative nature of the Perry suit but scoffed at its chances; the Newburgh News described it cynically as “a case where a negro is worth $20,000 more dead than alive.” Perry assured Orange County newsmen that the case was already attracting attention, certainly a chief objective in and of itself, although at one point he seemed to compromise his movement’s implied opposition to extrajudicial violence by declaring that “Lewis was merely a cat’s paw in the hands of P.J. Foley, and if anyone deserved lynching it was he.”

Per the consoling words of the Reverend Taylor at Lewis’s funeral, Port Jervis’s Black community, while profoundly shaken, had remained peaceful over the summer and showed no inclination to retaliate for the lynching. Some perhaps hoped that actual restitution might be won through Perry’s lawsuit, or were simply encouraged by the strong critique of white authority the suit articulated. A likely more consequential threat to local white hegemony, however, came in words directed by one Black Port Jervian to local white Republican officials—the coroner, district attorney, sheriff, and judges—that a failure to bring convictions against the lynch mob would greatly diminish turnout for Republican candidates in the fall election. “If Lewis’s murderers are allowed to go unpunished, mark my words, the Republicans won’t carry Orange County this fall, or for many years,” recorded the Middletown Daily Argus. “For years they have professed to be the friends and protectors of our race. Let them prove it, now that opportunity offers.”

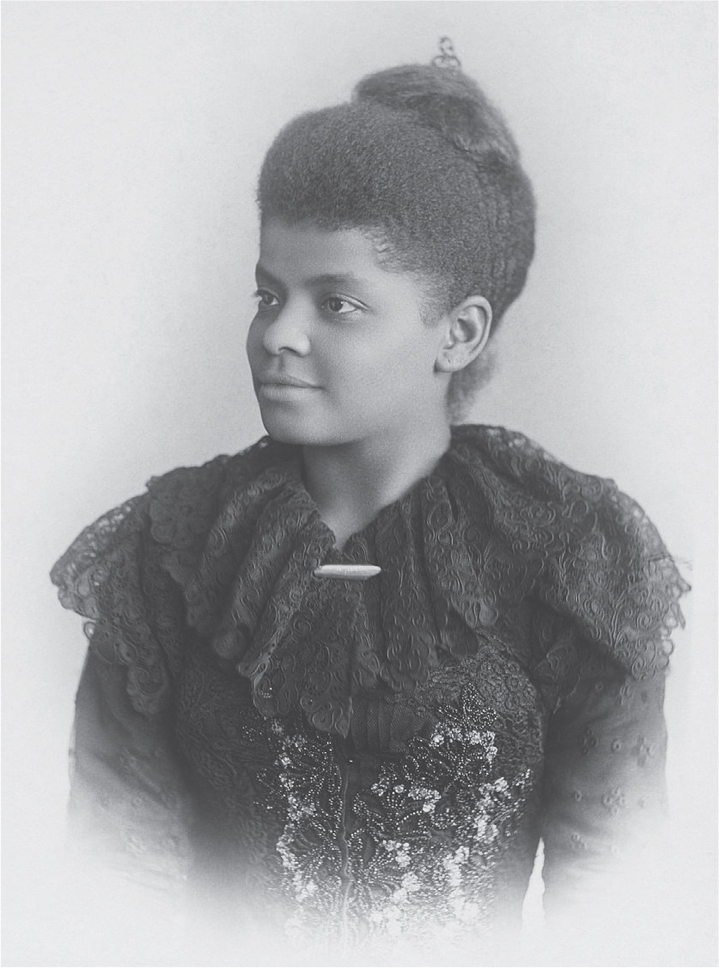

There were few people in America better able than Ida B. Wells to think critically about what had occurred in Port Jervis. The young African American journalist from Holly Springs, Mississippi, had, through her Memphis writings of the 1880s and early 1890s, established herself as one of the sharpest minds in the nation’s press. Yet she had learned the dark reality of lynching in the worst possible way—not as a reporter but through personal loss. As recently as the fall of 1891, “like many another person who had read of lynching in the South,” Wells conceded, she “had accepted the idea … that although lynching was irregular and contrary to law and order, unreasoning anger over the terrible crime of rape led to the lynching, that perhaps the brute deserved death anyhow, and the mob was justified in taking his life.” This impression evaporated swiftly in March 1892, when her friend Thomas Moss and two of his Memphis business partners, Will Stewart and Calvin McDowell, were arrested on trumped-up charges for repulsing an attack on the store they owned, the People’s Grocery, then stealthily taken from jail in the middle of the night and lynched. Their actual “crime” had been to operate a business that competed with one belonging to a white man.

Manufactured allegations of various kinds, Wells found upon further inquiry, were at the heart of many other lynchings, although a good number involved the most inflammatory charge, a sexual offense against a white woman. The latter could be relied on for purposes of incitement, so it was often included, no matter the original cause of complaint. And because whites viewed any intimacy between a Black man and a white woman as criminal sexual assault and refused to acknowledge the possibility the relationships were consensual, the likelihood of lethal consequences was ever present. By early May 1892, Wells had grown contemptuous enough of this hypocrisy to declare in the Free Speech and Headlight:

Nobody in this section believes the old threadbare lie that Negro men assault white women. If Southern white men are not careful, they will over-reach themselves and a conclusion will be reached which will be very damaging to the moral reputation of their women.

Publishing such volatile words in the South in the early 1890s was beyond asking for trouble; it was suicidal. Wells, however, who stood no more than five feet tall, had never lacked for daring. Following the deaths of both her parents in a yellow fever epidemic in 1878, when she was sixteen, she had refused to hand her several younger siblings off to the care of relatives and instead assumed sole management as head of her family. She taught at a one-room country schoolhouse in Mississippi, and later in Memphis, where she dabbled in literary and theatrical club life and contributed articles to local African American newspapers. Her early pieces dealt with household and women’s health issues, but she soon branched out, penning eloquent critiques of politics and the struggle for equal rights. Of a decidedly activist bent, she once bit a conductor who tried to physically evict her from a first-class railroad car, and in a similar incident in 1884, she brought and won a lawsuit after she was driven from a “ladies’ car” and sent to the Jim Crow “smoking car” of a train. A DARKY DAMSEL OBTAINS A VERDICT FOR DAMAGES AGAINST THE CHESAPEAKE & OHIO RAILROAD: WHAT IT COSTS TO PUT A COLORED SCHOOL TEACHER IN A SMOKING CAR—VERDICT FOR $500, the Memphis Daily Appeal headlined its account. The award, however, was successfully appealed, the state supreme court ruling that her sole intent had been to harass the railroad.

In May 1892, when her incendiary words about white women and lynching ran in the Free Speech and Headlight, she was in New York City. In her absence the paper’s offices were vandalized, while the Memphis Scimitar, assuming the author of such a calumny to be a man, threatened “to brand [the editor] in the forehead with a hot iron and perform upon him a surgical operation with a pair of tailor’s shears.”

T. Thomas Fortune had long followed Wells’s Memphis writings and, aware that she could not safely return home, offered her work on the Age. In exchange for the subscription list of the Free Speech and Headlight, he and co-owner Jerome B. Peterson gave her a quarter interest in the Age and a salary to write weekly pieces about the South. “Having destroyed my paper, had a price put on my life, and been made an exile from home for hinting at the truth, I felt that I owed it to myself and to my race to tell the whole truth now that I was where I could do so freely,” she vowed.

“Miss Ida B. Wells has added her vigorous pen to the pugnacious quill-quivers of the New York Age,” applauded the Detroit Plaindealer. “If those sneaking, cowardly, Negro-hating Memphis copperheads think they have gained anything by this arrangement, they are welcome to it.” Indeed, Wells lost no time in returning to her criticisms. In a June 25 article for the Age, she noted that “the miscegenation laws of the South only operate against the legitimate union of the races; they leave the white man free to seduce all the colored girls he can, but it is death to the colored man who yields to the force and advances of a similar attraction in white women.”

Her June 25 comments were part of a seven-column Age exposé titled “The Truth About Lynching,” in which Wells provided numerous dates and names involved in known lynchings and attacked the overworked reports that Black men were raping white women. Ten thousand copies of the issue were distributed, one thousand in Memphis alone, the first excerpts of what would become Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases, Wells’s book debut and the country’s first incisive outline of the lynching plague. It showed convincingly “that lynching represented the very heart, the Rosetta Stone, of America’s troubled relationship with race,” notes one appraisal of the book’s publication, and helped establish Wells as a national figure.

The next month, Frederick Douglass, writing in the influential North American Review, lent the issue historical perspective, terming lynching by whites a response to Black people’s advance since Emancipation. “I have frequently been asked to explain this phase of our national problem,” he wrote. “I explain it on the same principle by which resistance to the course of a ship is created and increased in proportion to her speed. The resistance met by the negro is to me evidence that he is making progress.”

Despite Wells finding a home in New York, she learned that whites’ personal contempt for women of color was a Northern fact of life as much as a Southern one. Once, while commuting on the Fulton Street ferry, she was rudely shoved by a white man who cursed at her. She also discovered that the one thousand miles separating Memphis and New York City offered no guarantee of safety. Memphis whites had at last realized that it had been “that Wells wench” who had so cruelly libeled them, and the Black-owned Kansas City American Citizen reprinted their threat to “put a muzzle on that animal … We are onto her dirty sneaking tricks. If we get after her, we will make her wish her mother had changed her mind ten months before she was born. We have been to New York. Are we understood?”

Such a violent threat against a Southern journalist in exile, let alone a female journalist, was unnerving, particularly as it evoked the mood of surveillance and terror that had characterized the fugitive slave era of the antebellum years, when white slave catchers infiltrated the North, often working with corrupt Northern police and judges to capture self-emancipated Black people and return them to slavery. While sympathetic to her plight, the American Citizen questioned the sagacity of Wells’s having humiliated white men in print in the pages of the Free Speech and Headlight. “Some medicine will not stay in the stomach when taken. Small doses, sugar-coated, would do better,” it advised. “God could have made the world and all in it in one minute. He chose to take six days, in order, if for nothing else, to teach the Negro patience, moderation and conservatism.”

Wells could not have disagreed more. She used strong words and had little patience for things half said, or for anyone who appeared willing to accept lynching as just the way things are. Her criticisms did not fall solely on the heads of lynching’s apologists but were at times directed at prominent progressives. Frances Willard, president of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union and one of the country’s most revered reformers, was taken to task by Wells for excusing lynching as an unfortunate outcome of Black men’s weakness for drink, which Willard believed rendered them helpless to control their sexual urges; the result in the South, Willard had claimed, was that “the safety of women, of childhood, of home, is menaced in a thousand localities at this moment so that [white] men dare not go beyond the sight of their own roof-tree.”

For Wells the perfidy of alleged Northern allies was one thing; the violent threats of Southern racists, who in print called her a “wench” and a “saddle-colored Sapphira”—or, as in the case of the Memphis Scimitar, offered, were she to return, to strip her clothes off in some public place and whip her in the manner of a slave—quite another. Wells was one of the first civil rights activists to understand that the hateful words of white people, especially pompous Southern officials and newspaper publishers, cited verbatim, worked as effective propaganda, depreciating the offender’s voice as it highlighted the reasonableness of her own.

Her writings in the Age soon brought her to the attention of Victoria Earle Matthews, a Brooklyn journalist, and Maritcha Lyons, a teacher, who arranged a talk for Wells at Brooklyn’s Lyric Hall on October 5, 1892, with the aim of raising enough money for her to expand her anti-lynching work. Wells had taken elocution lessons as a young woman in Memphis, briefly entertaining thoughts of becoming an actress, but speaking before a packed house of prominent New York women reformers, as well as some who had traveled from Boston, made for an intimidating debut. She became so overwhelmed sharing the story of the early loss of her parents, and the vitriol aimed at her for having placed herself at the head of a campaign to halt lynching, that she could not keep her emotions in check. She broke down and for several moments was unable to carry on with her address.

It is difficult today to contemplate the crisis of the human heart, mind, and spirit that lynching presented, in its sickening depravity and nauseating frequency: corpses found in the morning hanging from trees; spectacle “executions” attended by picnicking crowds; victims immolated and dismembered, their ears, fingers, and private parts sold as souvenirs; picture postcards made of such atrocities—all accomplished with complete disdain for the rule of law and often with passive or direct police collusion. Surely others shared Wells’s fear and concern, but for a considerable time it must have seemed that she alone had stared directly into the abyss and knew the magnitude of the crisis.

Wells had to signal to other women on the platform to bring her a handkerchief so that she could wipe the tears from her face and continue. “Respectability was among the highest goals of middle-class Black women after the degrading experiences of slavery,” the biographer Linda McMurry writes of the incident. “Without the backing of wealth and family, Wells had probably felt at times like an outsider in the elite social circles of Memphis.” The warm reception by the women gathered in Lyric Hall “was a precious gift at that point in her life.”

Wells returned the gift in kind. Regaining her composure, she blasted with a fiery eloquence the vindictive, unchangeable South, which, despite its loss in the Civil War, refused to reform and was instead taking the region backward in time, introducing strains of torture and violence as spectacle unseen since the days of the Roman Colosseum. With imagery that would echo in Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” address decades later, she called on her listeners to reawaken the great moral energies of the abolition movement, so as to

rouse this nation to a demand that from Greenland’s icy mountains to the coral reefs of the Southern seas, mob rule shall be put down and equal and exact justice be accorded to every citizen who finds a home within the borders of the land of the free and the home of the brave. Then no longer will our national anthem be sounding brass and tinkling cymbal, but every member of this great composite nation will be a living, harmonious illustration of the words, and all can honestly and gladly join in singing “My country! Tis of thee / Sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing / Land where our fathers died / Land of the Pilgrim’s pride / From every mountain side / Freedom does ring.

The event, described by the Washington Bee as “one of the finest testimonials ever [given for] an African-American,” raised $450, far surpassing expectations. No one was prouder than Frederick Douglass, who wrote in a preamble to Southern Horrors, “Brave woman! You have done your people and mine a service which can neither be weighed nor measured. If American conscience were only half alive … a scream of horror, shame and indignation would rise to heaven wherever your pamphlet shall be read.”

Douglass’s praise, it has been suggested, represented a kind of generational transfer of the Black struggle in America, from his lifelong battle for emancipation and equal rights to a young woman’s determination to secure an equally prodigious goal, an end to white terror and the bloodlust of the mob.

June 1892, the month and year of the lynching at Port Jervis, as well as the beginning of Wells’s advocacy on the national stage, marked the genesis of the anti-lynching crusade in America. This movement would accrue followers incrementally as lynching became, in the decades around the turn of the twentieth century, one of the very few issues impacting Black lives outrageous enough to arouse white concern. It also stimulated efforts by leading jurists and legal educators to examine what factors drove otherwise law-abiding citizens to take the law into their own hands, to become judge, jury, and executioner, or to stand by as dispassionate observers. The jurists’ probing led them to question traditional forms of criminal justice and their possible deficiencies.

No serious scholar of the law supported lynching, yet the experts challenged themselves to find ways to streamline criminal prosecutions in order to meet several aspects of the problem lynching represented: the people’s demand for retribution and punishment in something approaching real time; the belief that certain crimes could not be adequately punished by the courts; and the intense public frustration with the cumbersome rules and procedures of the justice system, of lawyerly double-talk, endless hearings, appeals, and obscure technicalities. In contrast, as a Delaware County, New York, paper argued with wry cynicism following Robert Lewis’s death, “Judge Lynch permits no long delays or serious interruptions. His decisions are rapid, forced, and final. He allows no appeals to be entered, but sees that his orders are enforced and his judgements executed with dispatch. He has presided for many years [and] is well and widely known. While some of his decisions have been questioned, none are reversed, and very many have been approved by the best citizens, as [the] case seems to be in Port Jervis.”

Certain cases brought these issues into sharp public focus. At the time of the Lewis lynching, a legal conundrum was working itself slowly toward resolution in New England; it centered on a white murderer named Frank Almy, whose much-publicized trial and long-delayed punishment had inspired numerous editorials critical of the law’s inertia.

Almy, a “handsome drifter,” had in 1890 been hired as a farmhand by the Warden family of Hanover, New Hampshire. He soon took a fancy to one of the Warden daughters, Christie, who reciprocated his amorous feelings. They walked the fields hand in hand in the evening and spoke of marriage. Her family, however, was far less enchanted with Almy, sensing, correctly as it turned out, that he was not who he pretended to be and was possibly some sort of grifter or criminal. In March 1891 her father refused to renew his work contract. Indignant, Almy left the property but returned secretly in early summer, making a hidden lair for himself in one of the barns. From behind its wooden slats, he could peer out and keep an eye on Christie. On July 17 he staged a surprise reunion with her as she strolled along an isolated country lane. Waving a gun to frighten away one of her sisters, he led Christie into the woods where, after a heated conversation and an alleged sexual assault, he shot her twice—once in the head, once between the legs. Investigators surmised she had rejected his plea that they run off together.

Dozens of lawmen and citizens scoured the hills for days without luck. Almy, it turned out, was right under their noses; he had gone back to his hiding place in the barn and managed to evade capture for a full month. He was caught only when he ventured out on a midnight foray for food.

Hanover was too small to have a jail, so Almy was held at a local hotel. To satisfy the public’s intense curiosity and forestall any attempt to lynch the prisoner, authorities allowed visitors to enter and file quietly past the murderer’s “cell,” peering in for a moment on the fiend, who was shackled to a bed. Sometimes, to their thrill and horror, he directly returned the gaze. After a photograph of the captive glancing up from his bed was published, letters and flowers from female admirers poured in.

Over the course of two trials, Almy played skillfully to the gallery, speaking movingly of his love for Christie and insisting his had been a crime of passion, for which he blamed her family. The adoration he enjoyed from lovesick women, along with the trials’ innumerable delays, infuriated a news-reading public (even as it remained glued to the story). Almy didn’t go to the gallows until May 16, 1893, almost two years after his crime.

The issues surrounding the lynching of Robert Lewis differed greatly from those raised by the example of Frank Almy—most significantly, Almy had received a trial, in fact two—but the press did not hesitate to connect the cases, linking the public frustration over what appeared to be the legal system’s overly considerate treatment of Almy to the Port Jervis mob’s rush to “execute” Lewis. “Bob Lewis’s crime was almost as atrocious as that of the New Hampshire murderer Almy,” Pennsylvania’s Honesdale Citizen noted, “and perhaps the leniency and spurious distinction accorded to that infamous ruffian by idiotic sentimentalists may have had something to do with the hasty justice of the Port Jervis people.” The Gazette went so far as to excuse Port Jervis’s rejection of the right to due process, saying that “lynch law is a terrible thing, but the man who possesses a decent instinct of respect for wife, mother, daughter, or sister, will prefer it a thousand times before the mockery of justice and law which permits a wretch like Almy to cumber the earth one hour after his guilt has been made known.” If such criticisms are an accurate gauge of public opinion, it’s possible Robert Lewis’s life was taken from him as swiftly and brutally as it was at least in part as a result of the courts’ perceived pampering of Frank Almy.

Other defenders of summary justice in the Lewis lynching spoke of the municipal savings realized, the Elmira News crediting Port Jervis’s actions as potentially helpful to cash-strapped jurisdictional coffers, since “a wretch was quickly disposed of and a good deal of expense saved.” Southern newspapers were known to make a related argument: that lynching offered a “shortcut” to an otherwise tedious civic duty, since the men who staged a lynching were, after all, likely the same men who would sit on a jury. Their service in “Judge Lynch’s court” was thus a no-cost alternative that achieved the same end.

The public disgust with justice overly deliberated and delayed brought forth many proposed reforms, including a return to corporal punishment such as public flogging and shaming rituals, both of which, it was proposed, would satisfy an aggrieved citizenry, reduce recidivism, and save on the costs of incarceration. To deal with sexual assaults, a few authorities, led by Judge Simeon E. Baldwin of the Connecticut Supreme Court and a founder of the American Bar Association, were willing to consider castration, “the surgeon’s remedy,” a vengeance admittedly so heinous it was expected to not only discourage rape but also diminish lynching, since even the most pent-up mob might be placated if assured that so exacting and appropriate a punishment awaited the accused. To expedite the law generally, experts weighed the elimination of peremptory challenges in jury selection, the abolition of the unanimity requirement in jury trials, and the suspension of the right of appeal.

As critics of these reforms pointed out, however, the law as practiced was already imbued with elements of vigilantism, emotionalism, and summary justice, biases that “chose” which criminals to suspect, arrest, and hurry to judgment, and influenced their sentences. This condition was present throughout the justice system, from the august figures who sat on the highest courts to the beat cop menacingly twirling his baton. Once would-be reformers recognized that removing some of the law’s safeguards would not so much discourage lynching as increase the ways in which the justice system already resembled it, the urge for drastic change lost much of its fervor.