Karl Lagerfeld and Inès de la Fressange at Chloé, Paris, 1983. Photograph by Pierre Vauthey.

{© Pierre Vauthey/Sygma/Corbis.}

Karl Lagerfeld and Inès de la Fressange at Chloé, Paris, 1983. Photograph by Pierre Vauthey.

{© Pierre Vauthey/Sygma/Corbis.}

DURING THE EARLY AND mid-1980s, the enormous financial boom in the West and westernized Japan brought designer fashion back with a vengeance. Runway shows, which were becoming more elaborately and glamorously designed, were covered by the media, even appearing on television in fashion capitals like Paris and Milan. High fashion was going through a creative, maximalist phase, and European designers like Giorgio Armani, Christian Lacroix, and Karl Lagerfeld were embedding themselves in mass consciousness for the first time. But that cultural breakthrough was not only about the economic boom but also a result of the houses’ expansion of their newer licensing arms, which included widespread development of perfume and cosmetics businesses. These new brand avenues needed models to sell them to consumers, and as modeling agencies had established elaborate global scouting networks by then, the high fashion houses found those models in steady supply.

At the same time, after sexual liberation in the 1960s and the over-the-top decadent social behavior of the 1970s, the 1980s’ version of sexy took a turn toward a coquettish, newly conservative innocence with an emphasis on fitness. Models—if the images of them were neither deviant nor threatening—could make an impact posing in just a swimsuit, or even lingerie, without being perceived as approaching pornographic. With aerobics classes and videos the new craze, human bodies were now more visible in the mainstream as well as in high fashion.

The obsession with a fit, lean body led to a whole subindustry of posters and calendars built around images of celebrities and models. A big catalyst of this trend was the rising importance of Sports Illustrated’s swimsuit issue, which, first published in the mid-1970s and still thriving today, not only brought models to the attention of everyday men and women but also ensured them public notoriety and, in some cases, longer and bigger success than ever before. The same models who became swimsuit and poster stars also found a home toward the end of the decade with a burgeoning catalog company called Victoria’s Secret. The women who worked lingerie and swimsuit were built differently—they were generally larger-framed and bustier, and had more wholesome-looking faces than high fashion models. But in some cases, models would cross over from one category into the other, working both sides of the business. What was a rare double-track success then has become a template for modeling stardom that persists to this day, beginning with Christie Brinkley, who paved the way for Paulina Porizkova, Elle Macpherson, Tyra Banks, and, more recently, Gisele Bündchen and Karlie Kloss.

With new markets opening internationally, the advertising business grew ever more powerful, and models responded by dropping the bad-girl antics of the 1970s and getting down to business. Exclusive brand representation became the order of the day. More women were entering the workforce worldwide, and more models realized the potential for lucrative superstardom on and off the runway.

Photograph by Mike Reinhardt, cover, Photo, June 1983.

{© Mike Reinhardt/Photo magazine.}

With her sunny good looks and buoyant personality, Christie Brinkley epitomized an American ideal of beauty: blond, athletic, friendly, unassuming, and seemingly ready for anything—like a high school cheerleader whose good looks and energy actually improved after graduation. So thoroughly did she embody this upbeat American spirit in her heyday that major brands as diverse as Noxzema, Revlon, Clairol, Breck, Diet Coke, and Anheuser-Busch made her the face of their products.

Christie is in that small group of models who have appeared on more than five hundred magazine covers, and hers range from American Vogue to Rolling Stone to the bestselling issue of Life of all time. The list also includes Sports Illustrated’s swimsuit issue, which featured Christie on the cover three years consecutively (1979 to 1981), during the time when the magazine’s popularity was rising precipitously. Its growth was catalyzed by the 1978 photograph of Cheryl Tiegs in a nipple-baring fishnet suit that catapulted the swimsuit issue into a thrilling, controversial, and much-anticipated annual event. So firm did its cultural footprint become that even now, Christie, in her sixties, is ranked sixteenth on Men’s Health’s list of the “100 Hottest Women of All Time,” beating out Gisele Bündchen, Cindy Crawford, Beyoncé, and Jayne Mansfield. Clearly, men have always loved her, but with her approachable, warm look, Christie has also been able to inspire and sell to women. With an agreement with CoverGirl that was renewed for twenty years, she once held the record for the longest contract with a cosmetics company. (Christie even broke that record herself, signing back on in 2005 to tout a line for aging skin for five years, though Andie MacDowell, for L’Oréal, has since edged her out.)

Christie’s career began in 1973, in Paris. She was there studying art, and the story goes that she was talked into posing by a photographer who spotted her on the street. Christie thought models were skinny snobs, and she didn’t really care about fashion, but she needed money—working part-time as an illustrator wasn’t paying the bills. Her pictures landed at Elite Model Management, which saw in her all-American looks greater potential on her native turf than in Europe and urged her to pursue her career back in the United States. By this time, Christie was homesick and happy to go along with the plan. Once home in California, she had lunch in Los Angeles with a US-based affiliate of Ford Models, and left the restaurant that day having booked three national advertising campaigns, one of them Noxzema, after executives at those companies, who were also in the dining room at the time, dropped by their table.

Photograph by Chris von Wangenheim, Vogue, 1977.

{Von Wangenheim/Vogue; © Condé Nast.}

In the mid-1970s, when Christie began her rise to the top of the modeling industry, America was in turmoil: the economy was poor, there was a severe energy crisis, and there was ongoing social unrest, which all had people yearning for simpler, easier times. The same impulse that ushered in Ronald Reagan’s presidency—a wish for optimism in politics to assure a better daily life for Americans—was reinforced by Christie’s wholesome, all-American visage. Hers was the look of the moment—and she was smart and ambitious enough to capitalize on it.

Christie is noteworthy because she’s achieved an unprecedented level of entrepreneurial success as a model. By the early 1980s, already a hit with major advertisers and mainstream fashion magazines with huge circulations, Christie was one of the first to transcend representing other brands by becoming a brand herself—one that she developed carefully and managed personally. She was the first model to produce her own calendar, and she wrote a beauty and fitness book that became a New York Times bestseller. Though she never considered herself part of the fashion industry, Christie had—and continues to have—such a universal appeal that in the mid-1980s, she did what many would consider unthinkable; she posed for two vastly different audiences without confusing people about her image, appearing on the covers of Playboy and Harper’s Bazaar in the same month. Other models, including Cindy Crawford and Stephanie Seymour, would later follow this path, but Christie was the originator.

Christie has gone on to dabble in acting, but her real focus now is activism, where she has proven once again that being a sunny blonde with an easy smile can be a powerful thing. Thanks to her unique ability to reach people and her tenaciousness, she hasn’t just been a voice for nuclear safety; she’s addressed the United Nations and the US Senate on the subject. She’s won humanitarian awards from the March of Dimes and American Heart Association, special recognition from the United Service Organizations for the tours she did throughout the former Yugoslavia and Kosovo, and a Merit Award from the Make-A-Wish Foundation.

“WHEN WE STARTED OUT WE WERE CLOTHES HANGERS AND WE WERE TOLD THAT BY THE TIME WE TURNED 30 WE WOULD BE CHEWED UP AND SPAT OUT. I’M AMAZED AT HOW LUCKY I’VE BEEN.”

—CHRISTIE BRINKLEY, from “Christie Brinkley: My Uptown Whirl,” by Helena de Bertodano, Telegraph, July 10, 2011

Though Christie’s appeal and power as a model was always in her approachability and wholesomeness, making deceptively simple images for a mass audience, her acumen and intelligence, on full display for more than thirty years, have put lie to the once dominant idea that a model is just a pretty face.

Photograph by Bruce Weber, British Vogue, 1991.

{Bruce Weber/Trunk Archive.}

Brooke Shields broke into modeling when she was just eleven months old. Thanks to her ambitious mother, Teri, who was her longtime manager, she appeared in an advertising campaign for Ivory Soap, which was shot by Francesco Scavullo. With Teri carving out the way, Brooke went on to become one of the world’s most successful child models, with Eileen Ford expanding her business to include models under age seventeen just so that she could represent Brooke. By age thirteen, Brooke had already been featured as one of People magazine’s twenty-five most interesting people. By the age of fourteen, she had appeared three times on the cover of Vogue and was the youngest person to have done so; in 1981, a Time magazine cover story listed her day rate as $10,000.

At the same time she was modeling, Brooke began to appear in movies, which is where her image took on a sexually provocative edge that shadowed her throughout her early career. Teri Shields had a bold sensibility and started early, pushing to get Brooke, then twelve years old, the title role of a child prostitute in Louis Malle’s 1978 film, Pretty Baby. At the time, movies in which girls played roles far beyond their years were almost commonplace as well as a winning strategy for acclaim, as exemplified by Jodie Foster (Taxi Driver) and Tatum O’Neal (Paper Moon). In Pretty Baby, Brooke turned in a solid performance. There are nude scenes in the film, but the exaggerated controversy around them makes the actual film seem chaste by comparison. Pretty Baby resulted in Brooke entering her most visible years with an aura of scandal about her—which Teri fueled by helping her secure other racy roles, like The Blue Lagoon, which Brooke did at the age of fourteen, with a body double.

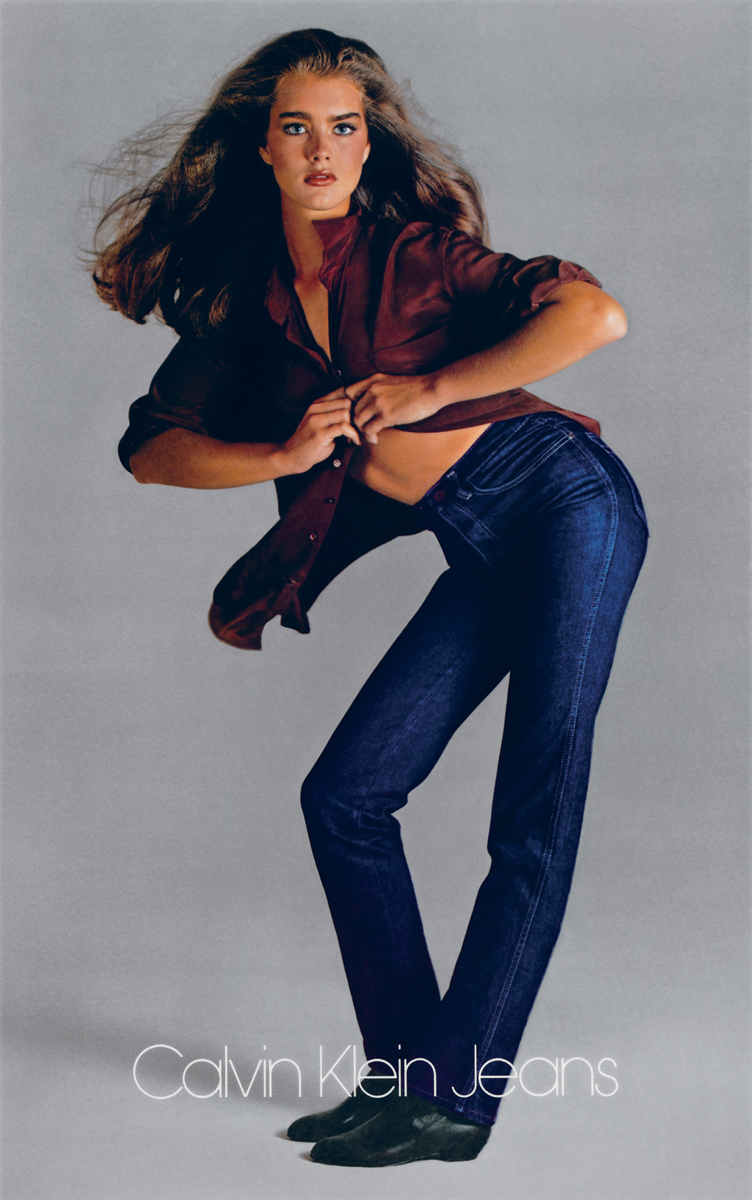

All the while, Teri did everything possible to present her daughter as a normal teenager to the media. But there was no getting around the fact that even if teenage Brooke roller-skated, rode horses, and received a five-dollar-a-week allowance like other kids, she was extraordinary, not just because of her penetrating beauty but also because of her precocious ability to express allure, sensuality, and innocence all at once. There’s no better example of this than the series of advertisements Brooke did for Calvin Klein Jeans in 1980, in which she would quote scientific theories or read the dictionary, or writhe on the floor, or ask the viewers, while her knees were open quite wide, if they wanted to know what came between her and her Calvins. (Answer: nothing.)

Brooke seemed to take the fast track of fashion and entertainment in stride, continuing to rack up one success after another, whether as a model, where her magazine and advertising work continued, or as an actor, where she won the People’s Choice Award for favorite young performer four years in a row, from 1981 to 1984.

In its double-headed nature, Brooke’s career is important because it represents a shift in the cultural view of modeling. In the past, models who hit it big outside of the fashion world generally stopped posing for fashion magazines or in designer advertising, as evidenced by the careers of models like Lorraine Bracco, Ali MacGraw, and Cybill Shepherd. But by the 1980s, modeling itself had become a big enough business to retain girls after they had become celebrities, like Andie MacDowell. It was no longer a stepping-stone to something bigger—it was big enough on its own.

So even while Brooke was a household name, even when she scaled back on her acting work to attend Princeton University in 1983, she never stopped posing. Throughout the 1980s, she was on the covers of international editions of both Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar. She was popular at Seventeen, Cosmopolitan, Mademoiselle, and Glamour. In 1989, Vogue declared her the face of the decade, and People and Time covered her film work, despite the fact that she didn’t maintain her early success as an actor.

Nonetheless, Brooke concentrated mostly on acting in the ensuing years, working hard onstage and on television to live down the critical drubbings that had accompanied her early box-office successes. She starred in a popular sitcom in the 1990s, Suddenly Susan, but she only broke the curse of being underestimated as an actress in 2003 when she took over the lead role in Wonderful Town from Broadway heavyweight Donna Murphy and won rave reviews. In 2013, she directed a three-day run of Chicago at the Hollywood Bowl, which earned critical plaudits as well.

Brooke has also gone through her personal—yet very public—ups and downs, which makes her later success so satisfying. She has for so long attracted outsize attention, and sometimes ire, that it feels like she’s been with us, and we’ve been worried about her, forever. Her brief marriage to Andre Agassi, which ended in divorce in 1999, coincided with the first real downward slide of his career, earning her the unfair animosity of tennis fans the world over. When she wrote her 2005 autobiography, Down Came the Rain: My Journey Through Postpartum Depression, she ended up the target of bizarre public attacks from as unusual a source as Tom Cruise. So now that she’s once again being lauded for things she’s worked incredibly hard to achieve, it’s a victory that feels especially sweet. She has faced multiple moments in her career when she could have just faded away, but Brooke has continued to prove that it will never pay to count her out.

Calvin Klein jeans advertisement, 1980. Photograph by Richard Avedon.

{Photograph by Richard Avedon © The Richard Avedon Foundation.}

“I’M JUST A KID WHO HAS DONE THINGS THAT SOME KIDS HAVEN’T.”

—BROOKE SHIELDS, from “Pretty Baby at 13: One Horse, Three Movies, Beaucoup Bucks, but No Beau,” People, December 25, 1978

Photograph by Gilles Bensimon, Elle, 1985.

{Gilles Bensimon/Trunk Archive.}

While Christie Brinkley and Brooke Shields were changing what it meant to be a model for a mainstream American audience, across the Atlantic Ocean, in her home country of France, Inès de la Fressange became a national treasure very much inside of fashion. For the role she played in helping to revive Chanel, a house that would stand like no other for French values and taste, the “swarthy asparagus,” as she likes to call herself, is more than just a model. On her skinny, impossibly stylish shoulders sits no less than the image of French chic itself. Since Inès became a star at the outset of the 1980s, she has helped export it across Europe, into newly affluent Japan as well as to America, and then later—in her work as a brand ambassador for Roger Vivier, with her own brands, and as the author of a wildly successful Parisian style guide—to the world at large.

Inès, who grew up just outside of Paris, comes from a family of aristocrats and banking heirs, with a mother who was an Argentine model. With her tall, gangly, and angular frame, at five feet, eleven inches, and just 110 pounds, she was genetically predisposed to posing for a living, which was a good thing, because her parents were not terrific money managers, and she needed to earn a living for herself. She tried modeling twice as a teenager, on the suggestion of boyfriends, and it was only the second time, when she was seventeen, that it stuck. Inès wasn’t an immediate success; it took Kenzo Takada booking her for his hugely successful label Kenzo to bring her to the attention of the right people. Soon she was working regularly for French Elle, and that’s when Karl Lagerfeld took notice of her.

The year was 1983, and Lagerfeld had just assumed the head designer and creative director position at Chanel. To make a big splash with his potentially controversial, updated take on the brand, he needed a woman who could mythologize Coco Chanel, the founder of the house, without coming off as retro. In Inès he found a knockout who could call the designer to mind visually—she was a dark-skinned brunette, after all, with a strong brow and a bit of the garçonne insouciance always associated with Chanel. Inès, who has always been confident, witty, and carefree, also shared Chanel’s opinionated, articulate nature. Lagerfeld realized he had struck gold and signed Inès to an exclusive contract, the first time a fashion house had ever made such a commitment, especially with such potentially big stakes. She would appear in all of Chanel’s ads, be the face of its new perfumes, walk its runways, and appear at Lagerfeld’s side for numerous media appearances.

Inès’s innate elegance and good breeding were the perfect vehicle through which Lagerfeld could propose new ideas and push his vision for Chanel into the direction the times saw fit—more baroque, more pop, more elaborate. On the runway, she was like a panther, albeit a perfectly soigné French one, making direct eye contact with the audience, flirting, twirling, playing the coquette or the gamine or the snob, whatever the clothes needed.

So successful was Inès’s embodiment of this important French brand that she soon became an easily identifiable shorthand for French chic itself. So it was no surprise that when the French government, under President François Mitterrand, went looking for its latest Marianne, they chose her. Marianne is the historic symbol of postrevolutionary France, and her toga-clad guise has appeared on postage stamps and official busts since 1969, when the government started casting well-known French women to use as a likeness. The honor had previously been held by such icons as Brigitte Bardot and Catherine Deneuve, but in 1989, when Inès said yes, it went to a model for the first time. The only problem was that Lagerfeld considered the very idea boring and bourgeois. He threatened to send Inès down the runway wearing a dress covered in fleurs-de-lis, the symbol of the monarchy, just to poke the government in the eye. When she refused to wear the dress, their falling-out was too much for the relationship to survive, and her enormously impactful time at Chanel came to an end.

Inès then decided that working on the other side of fashion was more interesting than continuing to model full-time. She launched her own sportswear label in 1991 and gave it her all, but her stake in the brand was too low for her to be able to fight when her investors decided to close it down in 1999. Inès learned a lot through the experience, though, and so when Diego Della Valle was looking for someone to revive the storied Roger Vivier shoe company in 2002, he knew she had the energy, passion, and contacts to bring it back to life. Inès still works for Vivier today as brand ambassador. Her book, Parisian Chic: A Style Guide, was a New York Times bestseller. She then launched a collection of smartly tailored casual clothes with Uniqlo in 2013, and finally bought back her name in 2014 to relaunch her own stand-alone line. Still with the same willowy frame and beautiful cheekbones, and already posing frequently to promote her own brands, she recently became a face of L’Oréal. In her early fifties, she appeared topless on the cover of Madame Figaro, the widely circulated fashion insert of the French national daily newspaper Le Figaro. And she has popped back onto runways occasionally, too, once for Jean Paul Gaultier in 2009 and then again in 2010, in one of the happier full circles in fashion history, for Karl Lagerfeld at Chanel.

“PERFECTION IS A NIGHTMARE. A GREAT FRENCH WINE WOULD BE NOTHING WITHOUT THE TASTE OF THE OAK BARREL OR A TOUCH OF DUST.”

—INÉS DE LA FRESSANGE, from “This Is What ‘Parisienne’ Looks Like,” by Elaine Sciolino, New York Times, April 20, 2011

Jean Paul Gaultier, runway presentation, spring/summer 2009. Photograph by Patrick Kovarik.

{Patrick Kovarik/AFP/Getty Images.}

Photograph by Michael Thompson, Allure, 1994.

{© Michael Thompson.}

While a great many models are discovered by others, it’s rare for that to happen to one as relatively old as Isabella Rossellini, who started posing for pictures professionally at twenty-eight. The daughter of Ingrid Bergman and Roberto Rossellini, and the then wife of Martin Scorsese, Isabella was not exactly unknown in elite circles. But it took a portrait of her shot in 1980 by the photographer Bruce Weber in British Vogue for her to come to the attention of the fashion industry. The dreamy, faraway look in her eyes; the noble face so like her mother’s; the air of refined intelligence; the maturity that her “older” years brought even to her still images—all added up to a seductive, sophisticated antidote to the cheerful blond brigade that still dominated the big-money modeling world, even in the wake of the successes of Beverly Johnson, Janice Dickinson, and Gia Carangi. With a dark, educated air similar to that of Inès de la Fressange, Isabella was the thinking woman’s model, the anti-bimbo.

Isabella was raised in Rome and Paris, and when she was eleven, a scoliosis diagnosis resulted in her undergoing eighteen months of painful surgeries and wearing body casts to correct her growth. None of this could have given her much of a sense of her own beauty during her impressionable early adolescence, though no one who saw the girl could deny it was there. Isabella appeared in a few Italian movies and, when she was nineteen, came to New York to attend college, working as a translator and then as a part-time foreign correspondent on a comedic Italian news program presented by Roberto Benigni. In 1979, at twenty-seven, she married Martin Scorsese; they remained together for three years.

When Isabella appeared in the Weber photograph, which came about because the two were friends and he simply asked, there was a subsequent avalanche of interest in her from both fine art and fashion photographers. Richard Avedon, Helmut Newton, Annie Leibovitz, Francesco Scavullo, Robert Mapplethorpe, and Steven Meisel all lined up to photograph her. Isabella, who found modeling to be interesting work, less invasive and demanding than acting, dove in, soon racking up a string of covers on American and international editions of Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, Vanity Fair, and Cosmopolitan. In 1981, the French cosmetics giant Lancôme, looking to dust off its fusty image, signed Isabella to a $2 million annual contract, the highest in the business at the time. Two years later, Time magazine reported her modeling salary to be $9,000 a day.

Donna Karan advertising campaign, 1994. Photograph by Herb Ritts.

{Herb Ritts/Trunk Archive.}

“NOBODY ASKED ME HOW OLD I WAS. BY THE TIME I WAS SUCCESSFUL WITH COVERS OF VOGUE AND HARPER’S BAZAAR AND VANITY FAIR AND THE LANCÔME CONTRACT, SOMEONE ASKED HOW OLD I WAS. THEY ALMOST FAINTED WHEN I SAID 33.”

—ISABELLA ROSSELLINI, from “The Inheritance,” by Rachel Baker, New York, August 14, 2011

Though Isabella would stay with Lancôme for fourteen years, she turned her energy toward acting, where she developed an eccentric résumé, eschewing obvious pretty-lady parts for more counterintuitive, distinctive roles. Her breakout performance was in her then partner David Lynch’s 1986 film, Blue Velvet, and she has continued to work in film and television to the present day—and was named by People magazine as one of the fifty most beautiful people in the world in both 1990 and 1991. After Lancôme controversially terminated her contract when she turned forty-two—a nefarious trend that prevailed at cosmetics companies throughout the 1980s and 1990s—she countered by starting Manifesto, her own makeup and perfume company, in 1999.

Though Isabella has remained candid about her career as a model—she enjoyed posing but always rued the career’s generally short lifespan—she continues to work at it now and again, appearing in a campaign for Bulgari in 2012 to promote a line of handbags she created for the brand. But she spends much of her time now working on a bizarre and humorous series of short films about the sex lives of animals, Green Porno, informed by her decision in her midfifties to go back to school to study animal behavior. The series first appeared on the Sundance Channel, and she recently brought it to the stage at the Brooklyn Academy of Music.

The worlds that Isabella has worked in—fashion and film—tend to valorize pretty young women who smile and don’t make waves. But Isabella’s maturity and insightfulness, her outspokenness and originality, combined with her beauty, have given her lasting relevance, both as a model and an artist.

Estée Lauder advertising campaign, 1988. Photograph by Victor Skrebneski.

{© Skrebneski Photograph.}

Despite her strong, soulful face, with its sharp cheekbones and perfect symmetry, and her ability to project equal measures of warmth and froideur, Paulina Porizkova is uncomfortable with the idea of being beautiful. Not that you’d know it from her pictures, in which Paulina poses with a grace and confidence that make shooting her a great pleasure. But the unusual journey of her earliest years made her innately suspicious of media hype, and she has always seen through the modeling industry’s tendency to flattery.

Paulina was born in Olomouc in what was then Czechoslovakia, but when she was a toddler, her parents fled to nearby Sweden, and she spent her remaining childhood years living with her grandmother in Prostĕjov, looking after her younger brother. Her parents made a public bid to have their children join them, which turned Paulina into a cause célèbre in Sweden and the focus of an intense political pressure campaign against her native country. She and her brother were eventually allowed to join their parents, but the unwanted media fame made Paulina feel awkward in her new school, a fact that wasn’t helped by her tall, skinny stature. Feeling like an ugly outcast, she focused on developing her mind, working hard in school and studying classical piano.

When she was fifteen, Paulina had a friend who was hoping to start a career as a photographer and convinced her to let him take some pictures of her. She agreed, and when the pictures arrived at Elite Model Management in Paris, the photographer’s work didn’t stand out so much as did the model in the pictures. Elite courted Paulina eagerly, sending her an airline ticket to France. With her newly developed curves and brash personality—smoking, drinking, swearing, quoting Dostoyevsky—she was an overnight sensation. Sports Illustrated selected her for the cover of the 1984 swimsuit issue when she was just eighteen. When they chose her again for the cover in 1985, it was only the second time that a model would have consecutive covers since Christie Brinkley in the late 1970s.

Photograph by Brian Lanker, Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue, 1986.

{Brian Lanker/Sports Illustrated/Contour by Getty Images.}

With her wide-set, feline eyes, strong bone structure, and slender limbs, Paulina had the kind of look that could cross over from the more commercial world of swimsuit modeling to high fashion, something that was rare at the time. Models like Christie Brinkley were straddling both worlds, but mostly the direction went from fashion to mass, not the other way around. However, Paulina’s ability to convey mystery and sophistication was too good a fit for the fashion of the late 1980s, which was swooning over exotic, worldly Europeans who seemed beamed directly from crumbling palaces and James Bond–worthy casinos. Soon Paulina started to appear frequently on the pages and covers of Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, Cosmopolitan, Glamour, and Self. By 1988, Estée Lauder had made her the face of the brand for $6 million a year, breaking Isabella Rossellini’s previous record of $2 million with Lancôme. Paulina remained the face of Estée Lauder until 1993, when the cosmetics giant, citing the now familiar refrain that she had grown too old at age forty, let her go. By then Paulina had already made Harper’s Bazaar’s list of the ten most beautiful women, and People magazine’s list of the fifty most beautiful people twice.

“HAD YOU PLUNKED ME DOWN A CENTURY EARLIER, I WOULD HAVE BEEN A SALLOW, FORBIDDINGLY TALL AND ANGULAR CHICK WITH FEW MARRIAGEABLE PROSPECTS.”

—PAULINA PORIZKOVA, “Modeling Is a Great Job and a Sh*tty Career,” Huffington Post, February 16, 2011

Paulina’s second act has seen her exploring acting in the 1990s, and writing a column for the Huffington Post, a novel that came out in 2008, and a children’s book, illustrated by her stepson with Ric Ocasek, whom she married in 1989 and to whom she remains happily married today.

Photograph by Robert Huntzinger, Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue, 1990.

{Robert Huntzinger/Sports Illustrated/Contour by Getty Images.}

Elle Macpherson earned her nickname, “The Body,” for two reasons. To begin with, quite simply, she has a stunning physique. Broad-shouldered like a swimmer, she’s six feet tall and lean, with strong legs and feminine curves. Second, the name stuck because Elle began her modeling career feeling self-conscious about facing the camera head-on. She was more at ease emphasizing her body, so her body became her calling card and greatest strength. Nowadays Elle has figured out successful new ways to keep the Body relevant, with a massive lingerie business, a skin-care line, and a line of wellness products. But she didn’t start out with such ambitions.

The daughter of an engineer and the stepdaughter of a lawyer, Elle grew up in a Sydney suburb, and wanted to study law. At age seventeen, in 1981, she went to New York, looking for work during the year she took off between high school and Sydney University, and signed up for a short stint at Click Models. Her big break, which introduced her as a girl-next-door type, was being cast in a television commercial for the diet soft drink Tab, which aired in 1982. In the advertisement, she strolls on the beach in a bikini, a big, wide smile on her face, prompting other girls to rib their drooling boyfriends. The ad made Elle a star back home and a hot property in America. By 1984 she was working frequently for Elle, with its creative director, photographer Gilles Bensimon, whom she eventually married. (They stayed together for seven years.) Her nonstop work with Bensimon—she had a six-year run in which she appeared in every issue of Elle—spurred covers for Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, Cosmopolitan, and GQ, and, in 1986, Sports Illustrated’s swimsuit issue. Sports Illustrated was a perfect venue for athletic, earthy Elle, and she went on to dominate the magazine, appearing on its cover five times; she remains the record holder for covers to date. In 1989, Time put her on its cover, too, accompanied by a profile about her career. “The Big Elle,” they called her, presciently, as she went on to make even bigger moves in the ensuing years, always in the interest of running her own business.

After a few good years of being paid well as a model, Elle realized her top-earning years would be of relatively short duration and started to make a point of taking controlling positions in her endeavors. In 1989, when she was approached by a New Zealand–based lingerie company, Bendon, to represent its products, she suggested instead a licensing agreement and the creation of a whole new company together. Such an approach is common now for celebrities, but it wasn’t at the time, and it still isn’t for models. As part of the deal, Elle volunteered to give up her work for Victoria’s Secret, and she even deferred her salary for a share in the profits. It might have seemed like a gamble at the time, but the company that was born the following year out of that risk, Elle Macpherson Intimates, has since grown into an internationally distributed brand. It’s one of the bestselling lingerie lines in the world, generating more than $60 million in sales per year. At the same time, Elle set up her own parent company, forgoing an agent to handle her modeling, which was revolutionary.

Similarly, Elle is very much in command when it comes to producing her own images. After putting out a series of very successful calendars in the 1990s, in 1993 Elle played a small but memorable part in the film Sirens, in which she appeared fully nude. The film’s success set the tabloids on a furious hunt for existing naked pictures of her, and, realizing the extent of the interest in her naked body—it shouldn’t have been much of a news flash!—she decided to take matters into her own hands and pose for Playboy, enlisting Herb Ritts to take the pictures. When Elle began to host Britain and Ireland’s Next Top Model in 2010, she also became an executive producer, as she did for the first season of NBC’s Fashion Star in 2012. Again, she took greater risks, which paid off for her.

Elle has made other on-screen appearances, notably a five-episode arc on Friends in 1999 and 2000, but her businesses have remained her main focus—and she has spent her time and energy there wisely. After creating her skin-care company, The Body, with the British megapharmacy Boots, she cofounded Welleco, a nutrition company, on the eve of her fiftieth birthday. And yet, proving she could have it both ways, Elle also signed a three-year contract as a global ambassador for Revlon, which she renewed for another three years in 2010. Though she calls herself the “accidental executive,” Elle has earned numerous awards for entrepreneurship and design, even as she’s returned to the catwalk for Marc Jacobs at Louis Vuitton and continued appearing on major magazine covers.

“I HONESTLY DON’T LOOK IN THE MIRROR, EXCEPT FOR WHEN I AM WORKING, AND THEN I SEE AN IMAGE THAT SUPPORTS MY BRAND.”

—ELLE MACPHERSON, from “My Secret Life: Elle Macpherson, Model & Businesswoman, 47,” by Charlotte Philby, Independent, June 5, 2010

Photograph by Gilles Bensimon, cover, Elle, 1986.

{Gilles Bensimon/Trunk Archive.}