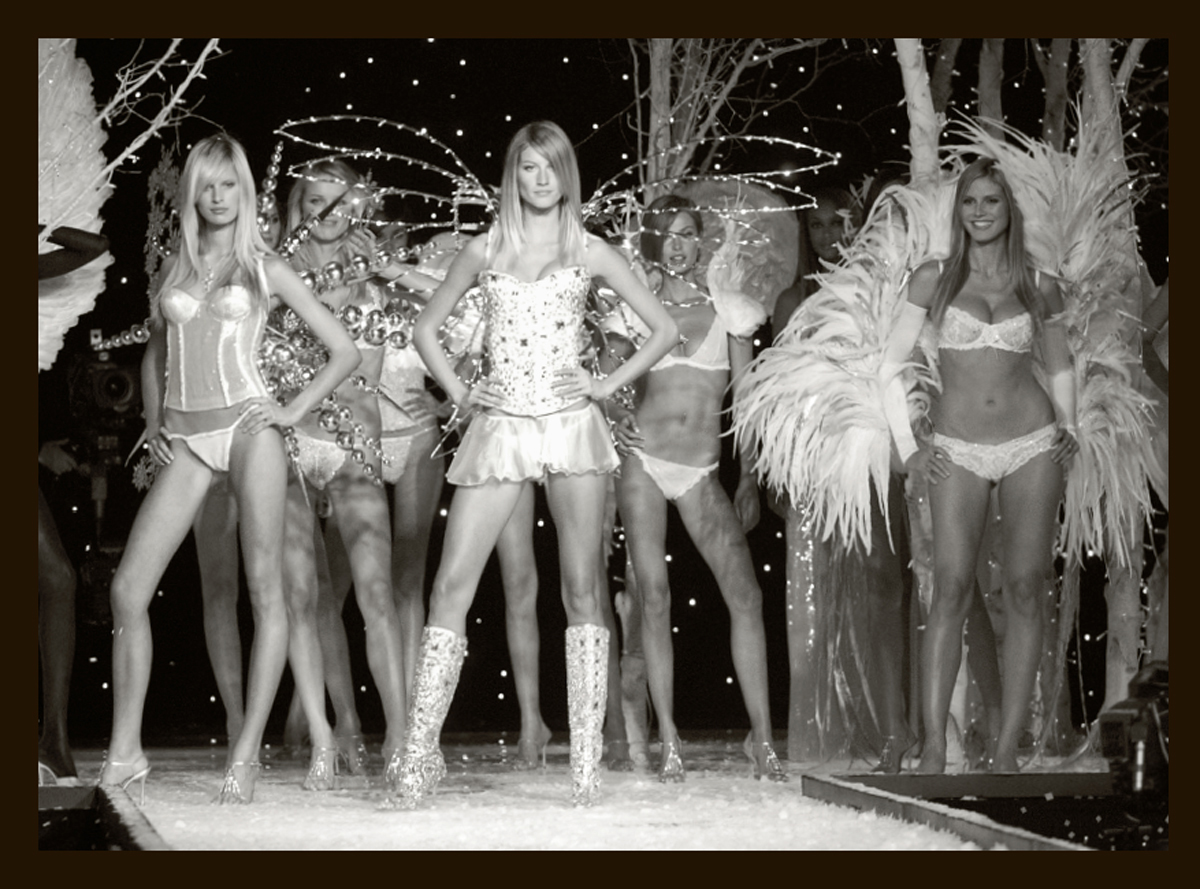

Victoria’s Secret show finale, 2001. From left to right: Karolina Kurkova, Eva Herzigova, Gisele Bündchen, Aurelie Claudel, and Heidi Klum. Photograph by Kevin Mazur.

{KMazur/WireImage/Getty Images.}

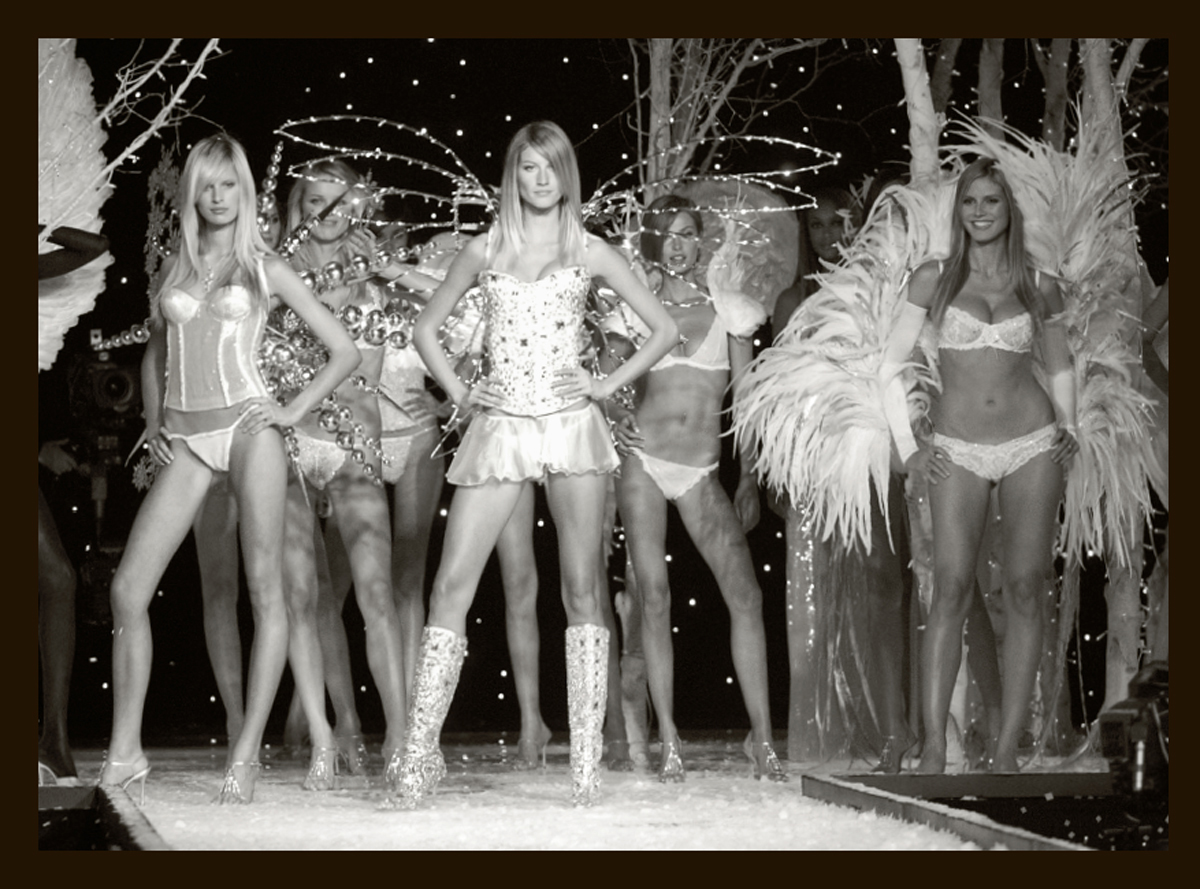

Victoria’s Secret show finale, 2001. From left to right: Karolina Kurkova, Eva Herzigova, Gisele Bündchen, Aurelie Claudel, and Heidi Klum. Photograph by Kevin Mazur.

{KMazur/WireImage/Getty Images.}

BY 2000, WITH NONSTOP CABLE news and the rising power of the Internet, we really were becoming a global village, with an almost universal curiosity about the world as it exists outside our daily experience. By this time, the Soviet Union had fallen, and dictators around the world were following suit, which meant that areas once ignored by fashion—Latin America and Eastern Europe, especially—were becoming accessible, as both new customer bases and new sources of modeling talent. Difference, exoticism, and uniqueness in models started to be calling cards, and increasingly, the ranks of the very top girls began to reflect the diversity of the audience—though we still have a long way to go. At the dawn of the twenty-first century, thanks to all of this opening up, there was less room for cynicism in both popular culture and fashion, and more of a desire to simply celebrate beauty and the optimism that it represents.

The rapid spread of technology, including the first Internet boom at the end of the 1990s, meant that fashion images could penetrate anywhere there was computer access. Thanks to the pioneering website Style.com, which went live in 2000, fashion shows were now not only running on a half-hour news magazine show on a cable channel but also visible in real time, with new depths of information, including tags identifying each model who walked the runway. But even if models were invading people’s computers and gaining a new level of ubiquity, and though the top girls could always name their price, the exaggerated fees and diva behavior of the supermodels were distinctly out of style. Anna Wintour, by then comfortably ensconced at American Vogue, started to almost entirely replace models with known celebrities as cover subjects.

Even as designers like Alexander McQueen were creating elaborate spectacles on the runway, and Dolce & Gabbana and Tom Ford at Gucci were turning up the sex appeal to nearly impossible levels, designers were producing more accessories and fragrances—all more affordable than ready-to-wear—than ever before. The cycle of deliveries of goods to stores sped up, which meant designers were sending more and more messages per year, and giving more opportunities for models. Brand logos became ubiquitous, in both the moneyed West and Asia, which had the effect of making fashion less elite.

As just-in-time production and the immediacy of runway photos became the norm, fast fashion—barely concealed knockoffs that hit the retail floor with astonishing speed—became a phenomenon. First sold in Europe at stores like H&M, Zara, and Topshop, fast fashion started moving to the United States, where these stores became a force of their own. With more access to trendy clothes, even if they weren’t original designs, and with more people around the world creating their own mix-and-match looks out of this less expensive clothing, the realm of fashion, once ensconced in an ivory tower accessed only by the wealthiest few, became a spectator sport for all social classes as well as an important new player on the pop-culture landscape. This meant that the models who sold it became part of the conversation on a still-more mass level.

Photograph by Matt Jones, i-D, 2006.

{Matt Jones/Trunk Archive.}

By the late 1990s, in Latin America, far from the centers of power in fashion, dictatorships were being overthrown and once lagging economies, like that of Brazil, were gaining momentum and opening up. Brazil had operated like a closed system for generations, but a series of market reforms meant that by the time Gisele Bündchen came of age in a southern province, Rio Grande do Sul, designer fashion was becoming more widely available in the country, and more and more girls were inspired to give modeling a try.

Statuesque, vibrant, with a powerful body and natural grace, Gisele has a way of making both men and women comfortable. Partly it’s because she’s naturally cheerful, a bit goofy, and unself-conscious. It’s why no one should have a hard time picturing the moment when Gisele was first discovered, at age thirteen, in the food court of a São Paulo mall. She is the proverbial Brazilian ideal, tall, tan, young, and lovely, with a prominent nose bringing just enough offbeat character to her face to make it interesting. When Gisele hit it big at the end of the 1990s, she pulled modeling out of a somewhat apathetic, contrarian, too-cool-for-school phase, embodying the sexiness and glitz that were coming back into fashion with her fierce warrior goddess comportment. She also put Brazil on the map as a prime target for model scouts, which helped the rest of the world get to know girls like Raquel Zimmermann, Isabeli Fontana, Alessandra Ambrosio, Adriana Lima, and Caroline Trentini, all of whom have gone on to their own forms of greatness.

Gisele’s story is not one of overnight success. It took almost three years of go-sees and auditions before her career took off, on the runway of Alexander McQueen’s spring 1998 “Yellow Rain” show, in which she strode like a race horse in impossibly high heels on a slippery, water-soaked runway. McQueen, who never designed for will-o’-the-wisps, loved Gisele’s strength, poise, and dynamism—and to see her walk the runway is to witness a bouncy prance with a jiggle and sizzle that can’t be beat. With McQueen’s vocal endorsement, Gisele’s bookings surged, and the following year she appeared on the cover of British Vogue, the first of her now 120 (and counting) covers across the magazine’s American and international editions.

In 1999, with campaigns for Missoni, Dolce & Gabbana, Versace, Valentino, and Ralph Lauren under her belt, Gisele starred in a Vogue feature called “The Return of the Sexy Model,” becoming the poster girl for the sea change in modeling that she helped bring about, as curves and sensuality were now in again. Not long after that story ran, you couldn’t open up a magazine without seeing at least ten pictures of Gisele—Gisele steamy, Gisele laughing, Gisele punching and kicking, Gisele flirty, Gisele nude. She managed to make all of it look easy, which it really isn’t. Anna Wintour called her the “model of the millennium,” and Gisele would prove totally up to the endorsement.

Photograph by Patrick Demarchelier, Vanity Fair, 2004.

{Demarchelier/Vanity Fair; © Condé Nast.}

“I HAD HEARD ABOUT GISELE, BUT WHEN SHE WALKED IN THE ROOM I FELT LIKE MY FINGERS HAD BEEN PUT INTO THE ELECTRICAL SOCKET, LIKE, PWOAH! PURE ELECTRICITY.”

—JOHN GALLIANO, from “Gisele: Supermodel Muse,” by Anamaria Wilson, Harper’s Bazaar, April 2009

Taking a page from moguls like Christie Brinkley and Cindy Crawford, as Gisele became the dominant model of her time, she signed contracts where she could turn on the sex in a supremely fashionable way, posing in ambitious, fleshy ads for Dior and becoming an important ongoing face of Dolce & Gabbana. These ads resulted in a five-year contract with Victoria’s Secret, which, coupled with her budding relationship with actor Leonardo DiCaprio, made Gisele a bona fide superstar. She was ready for all of it.

Maintaining strong ties to her native Brazil, in 2001 Gisele started a sandals company to rival Havaianas, called Ipanema, which helped catapult her onto the Forbes list of highest-earning supermodels for the first time in 2004—she holds the number-one spot today. Gisele has a seemingly endless energy for work; two years after she first topped Forbes, Women’s Wear Daily claimed that she was second only to Princess Diana in the number of magazine covers worldwide she’d appeared on in her lifetime. As a model, she defines “bankable,” to the extent that an American stock analyst created an index to compare the performance of the products she pitches to the rest of the Dow Jones Industrial Average. Not surprisingly, the products she endorses have come out ahead.

Gisele built a great career at a time when opportunities for models were shrinking. Now that she has two young children with the football star Tom Brady, she has slowed down her editorial work. But Gisele remains exciting to designers and cosmetics companies alike, across the high and mass spectrum, most recently starring in advertisements as disparate as Pantene and Louis Vuitton, H&M and Chanel. If there is a corner of the world that she has not dominated with her throaty laugh and disarming smile, then we simply haven’t discovered it yet.

Photograph by Patrick Demarchelier, Vanity Fair, 2006.

{Demarchelier/Vanity Fair; © Condé Nast.}

By the late 1990s, the fashion world had overdosed on “heroin chic,” and the industry could only play grunge’s anti-fashion card for so long before it went looking for new inspiration. It found it in Sophie Dahl. At a British size 14, the equivalent to a US 10, Sophie did not have the kind of proportions that designers and photographers were used to, but she had a laundry list of irresistible qualities: luminous sexiness, refined facial features, enormous eyes, and a rank fearlessness, which in her case was born of a peripatetic childhood and an unstable mother. She also had an impressive pedigree: Sophie came from a prominent family—her grandfather was the author Roald Dahl; her father, the actor Julian Holloway; and her mother, the writer, and girl about town, Tessa Dahl—so she knew to take the fashion industry’s posh glamour in stride. Because her family’s fortune was self-made, Sophie also understood what it meant to work hard.

Sophie was nineteen when she met the woman who was to become her fashion fairy godmother, the maverick stylist Isabella Blow. After a fight with her mother on Belgravia’s Elizabeth Street, Sophie had run off, and sat on a doorstep, crying. A vision wearing a Galleon ship on her head stepped out of a cab and asked Sophie who she was, why she was crying, and what she was doing on her doorstep. Then she asked whether she wanted to be a model. It was Blow, an eccentric, and an ingenious spotter of talent. Blow took her to meet knitwear designer Lainey Keogh, who cast Sophie in her first-ever show at London Fashion Week. Sophie walked with Naomi Campbell, Helena Christensen, and Kate Moss. Among such attention-getting company, Sophie’s confident sexiness and lack of self-consciousness made the headlines. Blow introduced Sophie to photographers Nick Knight and David LaChapelle, who were to shoot her for i-D and Vanity Fair respectively, on her first day of modeling. She also sent her to Sarah Doukas at Storm Model Management, who put Sophie to work in Elton John’s video for “Something About the Way You Look Tonight.” Cast alongside super-waif Kate Moss and a host of other international pretty people, Sophie stood out with her sass and pluck.

Though the plus-size modeling business had been operating as an adjunct to the mainstream industry since the 1970s, Sophie did not go to work for its big accounts, such as the women’s wear company Lane Bryant. Instead, she landed jobs with Richard Avedon, Karl Lagerfeld, Peter Lindbergh, and Mario Testino; modeled in campaigns for Versace, Alexander McQueen, and Patrick Cox; and appeared on the covers of Italian, French, and British Vogue, Elle, Harper’s Bazaar, Visionaire, W, and i-D, among others. Her very fashionable retro-dolly look and her lineage gave her the edge.

Photograph by Regan Cameron, British Vogue, 2007.

{© Regan Cameron/Art + Commerce.}

“MY MODELING CAREER WAS REALLY JUST A LONG ACCIDENT—ONE THAT HAPPENED TO COINCIDE WITH MY CHOCOLATE-CAKE PHASE.”

—SOPHIE DAHL, from “Sophie Dahl’s Voluptuous Cooking,” by Jen Murphy, Food and Wine, March 2010

Because fashion designers have never been in the habit of producing a range of sample sizes, Sophie ended up working nude more frequently than other girls, which, when added to her natural coquettishness, gave her a more sexy profile than many of her peers. It was only fitting, then, that Herb Ritts cast her in the 1999 Pirelli calendar, one of the modeling industry’s most prestigious erotic bookings. The following year, Tom Ford, a designer who knows a thing or two about utilizing sex to sell product, put her in his retooled Yves Saint Laurent Opium campaign, shot by Steven Meisel. Wearing only a necklace and a pair of gold sandals, with flame-red hair and bright makeup, Sophie writhed on a black satin sheet. The outraged response to the overt sexuality of the advertisement was deafening. It was banned in America and the United Kingdom, where it was the subject of so many complaints for objectifying women that it ranked number eight on the Advertising Standards Authority’s most-objectionable list. Meanwhile, there wasn’t a housewife north of Croydon who didn’t go out and buy a bottle of Opium, my mum included. It was as if the world was waiting for this kind of generous carnality, and Sophie became a light in the darkness for fuller-figured women the world over.

Sophie slimmed down as she entered her early twenties, and went on to enjoy an equally successful second incarnation of her modeling career, shooting campaigns for the likes of The Gap, Banana Republic, Boucheron, Burberry, and DKNY. Sophie always knew modeling wouldn’t last forever, and while she has continued to pick up cover work to the present day, by the turn of the 2000s, she started to explore other opportunities. She did some stage and film work before she settled on the family business of writing, which she’s turned out to have a talent for, first as a contributing editor at British Vogue and then Harper’s Bazaar UK, and then penning two bestselling novels. She also wrote two cookbooks, the first of which was adapted into the aptly titled The Delicious Miss Dahl, a six-part, primetime BBC cooking show.

Photograph by Guy Aroch, WWD Beauty Biz, 2008.

{Guy Aroch/Trunk Archive.}

Since Natalia Vodianova—whose delicate features and luminous skin give her the appearance of a china doll—really hit her stride as a top model at the turn of the millennium, at the age of seventeen, it’s as if she has eternally hovered in that poetic, fleeting meeting point between girlhood and womanhood. In that sense, there is a bit of the waif in her. Steven Meisel nicknamed her “the Baby” for her fragile look and the tenderness it inspires, especially in an age when women are increasingly powerful and in command. The crossroads between innocence and experience is always fascinating, and in Natalia it makes for an almost throwback or storybook quality, giving rise to a romantic kind of nostalgia that may sound retrograde but—given the fact that she is a fully grown, quite powerful woman—is harmless. That contradiction only makes her more fascinating.

Like many of her colleagues from the former Soviet Union, Natalia grew up in tough circumstances. Her mother was a fruitmonger at a Nizhni Novgorod market, and from when she was quite young, Natalia sold at her side, eventually running her own stand when she was just fifteen. There was no talk of fragility back then, and Natalia has said she only got the first inkling that she was attractive when she was wearing a new white pleather trench coat she had bought with her hard-earned money and some boys in the street called her pretty. (And then, in their inimitable teenage-boy style, they threw dirt on her.) She signed up at a local modeling school, and within a year, in 1999, she had been scouted and relocated to Paris. The following year she was on the covers of French Elle, Australian Marie Claire, and Teen Vogue, her career on a fast ascent—but almost as quickly, she became pregnant with the first of her three children with Justin Portman, a real estate scion.

“AN ICE BEAUTY. LIKE SOMETHING OUT OF NARNIA.”

—PHOEBE PHILO, from “In the Mood for Love,” by Sarah Mower, Vogue, February 2003

As Portman is one of the richest men in the United Kingdom, there was momentarily some question as to whether Natalia would focus on her career or her growing family. But Natalia herself entertained no thoughts of taking it easy, and in 2001 she got to work posing for Juergen Teller for Marc Jacobs while she was still pregnant. Right after giving birth, she got back into the game in record time. The year 2002 was a banner one for her, as she headlined Tom Ford’s fall show for Yves Saint Laurent, a particularly sexy collection, and became a face of Gucci and Louis Vuitton. In 2003 Natalia grabbed two major gold rings, the Pirelli swimsuit calendar, shot by Bruce Weber, and a contract with L’Oréal, signaling in no uncertain terms that she had arrived. She also appeared as Alice in a memorable and much-talked-about Alice in Wonderland–themed editorial for American Vogue’s December 2003 issue. Shot by Annie Leibovitz and styled by Grace Coddington, the multipage editorial featured Vodianova posing in blue dresses designed by top designers of the day—John Galliano, Tom Ford, Marc Jacobs, Donatella Versace, Viktor & Rolf, and others—all of whom appeared with her in the photographs dressed like characters from the children’s story. In 2005 she became the face of Calvin Klein’s Euphoria fragrance and, in 2008, added Guerlain to her roster of contracts. She continues to work at a fast pace, with a substantial and growing list of Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar covers across all their markets, her own lingerie line for Etam, and her charity, the Naked Heart Foundation, which aims to create safe play spaces and support families in troubled regions of Russia. In 2010, Natalia joined the short list of models to whom an entire issue has been dedicated, hers in the increasingly influential Vogue China.

The interplay of sweetness and wisdom in Natalia’s work strikes an almost uneasy balance between the naïveté of her huge, wide-set eyes and the power of her intense gaze. She brings a real depth of feeling, expressing emotion with raw frankness, and there’s something a bit forbidden about her appeal, as if she were forever just on the verge of being sullied. In an age when elixirs, potions, and surgeries are a frequent recourse for those unwilling to let go of their youth, leading the public to analyze the effects of every not-so-miracle cure, Natalia’s seeming agelessness is an impossibly alluring ideal.

Photograph by Vincent Peters, Numéro Tokyo, 2008.

{Vincent Peters/Trunk Archive.}

Photograph by Cliff Watts, Harper’s & Queen, 2004.

{Cliff Watts/Trunk Archive.}

The modeling world has always been a struggle for women of color, and when Liya Kebede first started at age twenty in 1998, after a film director spotted her in Addis Ababa and introduced her to a modeling agent, she was mostly booked for bland catalog work. She walked for Ralph Lauren and BCBG in 1999, but it was Tom Ford, in 2000, who boosted her career to a higher level, and to hear him explain the moment, it’s almost as if he had no choice. “I was casting models for a show, and Liya came in,” he wrote in a 2010 profile honoring her as part of Time magazine’s Time 100 issue, celebrating the most influential people in the world that year. “She looked me in the eyes, and I was quite literally stunned. . . . Later in the day, when trying to remember what she looked like, I could only remember her eyes.” So the eyes had it, but so did that cool, regal bearing, surrounded as she was by bouncy Brazilians and endless streams of Eastern European blondes. Ford cast Liya with an exclusive appearance in his fall 2000 show for Gucci, so sure was he that she would capture the attention of the industry. But Liya took her auspicious debut in stride, taking downtime in the aftermath to marry and give birth to a son, the first of her two children.

Photograph by Arthur Elgort, Vogue, 2006.

{Elgort/Vogue; © Condé Nast.}

“SHE’S AN EXOTIC GRACE KELLY. MODELS WORK FOR YEARS TO DEVELOP THE POISE, GRACE, AND STYLE THAT SHE CAME TO THE BUSINESS ALREADY EQUIPPED WITH!”

—JAMES SCULLY, from “Casting Agent James Scully’s All-Time Favorite Models,” by Kendall Herbst, New York’s Look fashion supplement, Spring 2009

When Liya came back to work in 2001, she did it in a big way, signing on as the face of Tom Ford’s Yves Saint Laurent. In 2002, she was featured not only on the May cover of Vogue Paris—a title the whole fashion world had locked eyes on due to its new editor, the influential former Ford muse Carine Roitfeld—but throughout most of the issue as well. The issue showed Liya in a stunning array of guises, proving that this charming girl with the soft, sweet smile could bring edge, sex, cool, and joy into high fashion, street fashion, and everything in between.

With her innate elegance and the stamp of approval of two such important power brokers, in the next couple of years Liya became the girl everyone wanted. She shot campaigns for Dolce & Gabbana, Louis Vuitton, Tiffany & Co., and the Gap; appeared on the covers of Russian, French, and American Vogue; and in 2003 became the first black model to sign a contract with Estée Lauder, worth $3 million. She has continued to represent brands of the moment in their moment, such as Lanvin, Balenciaga, Bottega Veneta, and Kenzo. Her editorial work has remained impactful, with regular spreads in several international editions of Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, W, V, Numéro, and i-D. Photographers like Mario Testino and Arthur Elgort, whose work veers toward soigné, grown-up glamour, swear by her. But she is also a regular with the more outré Steven Meisel and Mert and Marcus.

Although she’s been highly successful, Liya has never forgotten her roots. A vocal advocate for her native Ethiopia, she has created a line of casual contemporary sportswear, Lemlem, made by artisanal weavers back home, in an effort to keep alive an otherwise dying craft. In 2005, she became a goodwill ambassador for the World Health Organization for Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health. As she has approached acting little by little, she’s made conscious choices, taking on smaller parts in political films. Her first starring role was in 2010’s Desert Flower, based on the life story of Somalian model and survivor of genital mutilation Waris Dirie. The same year, when she had already scored spots on Vanity Fair’s International Best-Dressed List and Forbes’s list of highest-paid models, it was her humanitarian work that put her on the Time 100.

Photograph by Txema Yeste, Harper’s Bazaar, Spain, 2012.

{Txema Yeste/Trunk Archive.}

Photograph by Inez and Vinoodh, Vogue, 2008.

{Inez and Vinoodh/Trunk Archive.}

While the longevity of a modeling career in the twenty-first century has decreased due to increased competition among models, the public’s ever-diminishing attention span, and changes in the cultural climate, for some rare birds there is almost no limit to whom they can reach and for how long. One key to a long and storied reign, like that of Daria Werbowy, one of the most successful models in the last twenty years, is versatility—being able to convey almost any mood believably and embody the diversity of looks and genres in which the fashion industry now traffics. When there is no longer one reigning type, models who want enduring careers don’t have the luxury of being pigeonholed: they have to continually reinvent themselves and transcend the trends. Although Daria’s curves, athletic frame, and womanly, elegant face are a far cry from waifs and androgynes, recalling more the supermodels of the 1980s and 1990s, she has always been able to appeal to broad audiences.

Another key to a long career is strength of character and constitution, the ability to withstand the business’s ever-faster-moving pace and growing number of media and outlets. As capable of transforming herself as Daria is, she has a strong sense of self. Since starting work at eighteen, she’s taken the time, and occasionally the time-out, to develop her self-awareness. When the media writes about her, they like to mention that her last name, Werbowy, means “willow tree” in Ukrainian, her parents’ native language, because it’s a fitting moniker for someone so strong and supple, who can bend to the needs of the moment without breaking. Daria manifests power, both in her physique and enormous presence; she is a model whom other women feel no shame in admiring.

Born in Krakow, Poland, Daria immigrated to Toronto with her family when she was three. By fourteen, she had grown to her adult height, five foot eleven, and despite a mouthful of braces won a national modeling contest. She decided to wait to start modeling until she finished high school because she saw it simply as a means to put herself through art school. At eighteen, Daria signed with Elmer Olsen, a former scout for Elite Model Management, and went to New York to test her luck in her first runway season. Unfortunately, her timing was in sync with the events of 9/11: that year, New York’s spring Fashion Week fell on the second week of the month, which included the day of the bin Laden attacks. Everything stopped: the entire city was shut down, and the rest of the year was very quiet as the economy fell into a downswing. After eight uneventful months in New York, she returned to Canada, assuming she would pick up where she left off with local editorial work—and that would be that.

“GIRLS WANT TO LOOK LIKE HER—PERHAPS BECAUSE SHE LOOKS LIKE A WOMAN.”

—LAURA BROWN, “Daria: The Face of Beauty Now,” Harper’s Bazaar, January 2014

But in early 2003, Daria decided to give New York another try. Almost upon her arrival, she was booked by the star-making Steven Meisel for the first of three Prada campaigns. This booking triggered an avalanche of high-visibility work, including three Vogue Italia covers, also shot by Meisel, and editorials for Vogue Japan, Vogue Paris, i-D, W, Numéro, and The Face. In September 2004, American Vogue put her in a prime position of their gatefold cover, next to Gisele Bündchen and Natalia Vodianova, calling her one of the models of the moment.

American Vogue was being too tentative, for Daria has been a model of many moments. In 2005, after Karl Lagerfeld signed her to the first of five Chanel campaigns, she landed one of the most prestigious jobs in the business, becoming the main face of Lancôme—a job she has held for a decade. In 2006 she slowed down a bit to clear her head, and she did so again in 2012, when she took some personal time to travel and relocate to Ireland. But over the years, Daria has amassed contracts with Yves Saint Laurent, Valentino, Missoni, Versace, Isabel Marant, Diane von Furstenberg, David Yurman, Rag & Bone, Roberto Cavalli, Christian Dior, Balmain, Céline, H&M, and Salvatore Ferragamo. On the runway, she is also the model with whom many designers want to make their most lasting impression: she holds the record for opening and closing more fashion shows than any other model in history.

Despite having a low-key personality, favoring blue jeans, and playing basketball and snowboarding in her off time, Daria has become such a force within the modeling world that she is often bigger than the designers and magazines she works for, a status rarely seen since the 1990s, when supermodels of the decade ruled the runways—but without the attitude that toppled them.

Photograph by Inez and Vinoodh, Vogue Paris, 2012.

{Inez and Vinoodh/Trunk Archive.}