1

Surbigloom Blues

They come from quiet towns and near suburbs, terraced houses thrown up in the aftermath of German bombs. Places you don't see until you leave them, and why would you want to leave them, the same roses on the same trellises?

—Zachary Lazar, Sway (2008)

ALAN CALLAN (president of Led Zeppelin's Swan Song label in the U.K., 1977–1979) In 1977, I was at the Plaza Hotel in New York with Jimmy Page, and we were going out somewhere. It was absolutely pissing down as we walked out through the side door of the hotel to where the limo was waiting.

As the doorman takes us to the car, a woman standing in the doorway in a fur coat says, “What do I have to do to get some attention here? Look at these two with their jeans and long hair—how come they get a car immediately?”

The doorman says, “Well, ma'am, it's like this: the first guy there, he's been practicing what he's good at since he was six years old. If you went home and did the same, you'd probably get a limo when it rained.”

JIMMY PAGE I remember going onto the playing fields one day and seeing this great throng crowded around this figure playing guitar and singing some skiffle song of the time, and I wondered how he did it. He showed me how to tune it, and it went on from there: going to guitar shops, hanging around watching what people were doing, until in the end it was going the other way, and people were watching you.

ROY HARPER (maverick folk singer and friend of Zeppelin's) Skiffle was derived from both Southern country and Northern urban blues. We didn't really discriminate, though I have to say I thought the more authentic brand was the Southern country blues. Any self-respecting eleven- to fourteen-year-old with an ear was doing the same thing in the mid-'50s.

KEITH ALTHAM (reporter for New Musical Express in the '60s and early '70s) What spun out from Elvis was skiffle, which had at its heart folk and Leadbelly and Big Bill Broonzy, so the links started to point toward blues. When you went and bought your Lonnie Donegan album, you saw “New words and music by L. Donegan,” but the song was actually attributed to Leadbelly or Broonzy. So you went in search of those names.

CHRIS WELCH (reporter for Melody Maker from 1964 to the mid-'80s) Hearing Lonnie Donegan's “Rock Island Line” on the radio was such a shock. We'd never heard anything as ethnic or authentic. That was our introduction to American folk and blues, if you like. It was very much a school craze. We might once have collected stamps, and now we were out collecting blues records. My friend Mike bought a 10" Leadbelly LP and we'd sit listening to that for hours. Then we set about copying it and forming a skiffle group.

CHRIS DREJA (rhythm and bass guitarist in the Yardbirds) Jimmy Page was involved in skiffle because it was accessible. It was cheap. It was something you could do at a school concert.

JIMMY PAGE It was a process of accessing what was going on in skiffle, and then, bit by bit, your tastes changed and matured as you accessed more. There was the blues, there was Leadbelly material in Donegan, but we weren't at all aware of it in those days. Then it came to the point where Elvis was coming through, and he was making no secret of the fact that he was singing stuff by Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup and Sleepy John Estes.

KEITH ALTHAM Someone knew Jimmy's mother and knew that he was in a skiffle group that was appearing at the Tolworth Co-op Hall. So I went along to watch them with a couple of mates from school, and on comes this kid about three foot nothing with a guitar about four foot and proceeds to play the arse off it. It was extraordinary, a twelve-year-old. There I am at sixteen struggling with four chords. And that was it, as far as I was concerned: “If some twelve-year-old punk can play guitar like that, I may as well give up.”

CHRIS DREJA I grew up in Surbiton, which one wag nicknamed “Surbigloom.” Life was all about the unbelievable driving banality of the suburbs for anybody who had an ounce of energy and intelligence. It's amazing that Eric Clapton came from Ripley—under daunted circumstances, according to him—but he still frequented all the places I did.

KEITH ALTHAM Epsom was a quiet suburban racing town. The only time it was really buzzing was Derby Day. Lester Bowden's was the big store where everyone bought their clothes.

JIMMY PAGE It was still those somber postwar days of rationing in Epsom. Then this explosion came through your radio speaker when you were eleven or twelve. There were some good programs on TV, too, like Oh! Boy with Cliff Richard and Tony Sheridan. But Lonnie Donegan was the first person who was really giving it some passion that we related to.

GLYN JOHNS (engineer on the first Zeppelin album) Jimmy lived at one end of Epsom, and I lived at the other. The first time I ever met him was at the youth club at St. Martin's Parish Church. We had a talent competition. He was probably about twelve or thirteen. I'll never forget, he sat on the edge of the stage with his legs hanging over, playing acoustic guitar. And I thought he was fantastic then. Maybe there was something in the water, I don't know. It was strange, the three best British rock guitarists—Clapton, Beck, and Page—all coming out of this one little area.

CHRIS DREJA How ridiculous that white blues developed in this genteel area of southern England. What is a howlin' wolf when you live in Surbiton?

AHMET ERTEGUN (cofounder of Atlantic Records, Zeppelin's label) When I used to go to Keith Richards's house, that's all you'd hear all day long, the blues. Go to Eric Clapton's house, all you hear is the blues. It was a much more conscious effort to digest that music than Americans seem to have made, because Americans took it for granted and figured, “Well, the blues is here, it's part of our country.”

ELIZABETH “BETTY” IANNACI (worked in Atlantic's West Coast office, 1975–1977) I never heard “race music,” I never got those 45s. I heard Bo Diddley through the Rolling Stones. These boys got those records from the underground black market in England, and that was how I experienced blues first—through the Stones, through Alexis Korner, through Led Zeppelin.

MARILYN COLE (first wife of Zeppelin tour manager Richard Cole) Jimmy and his mother, Pat, were very close. Richard always said she had influenced him greatly.

DAVID WILLIAMS (boyhood friend of Page's) I am certain that Jim's mother was the initial driving force behind his musical progression. She was a petite, dark-haired woman with a strong personality, a glint in her eye, and a wicked sense of humor.

NICK KENT (New Musical Express journalist in the '70s and the '80s) Jimmy was very, very middle-class. When everyone else would say, “Fuck!” he would say, “Gosh!” It was the same with me—we both wanted to be wild and dangerous, but we didn't want our parents to know. Whereas working-class guys don't give a shit what their parents think.

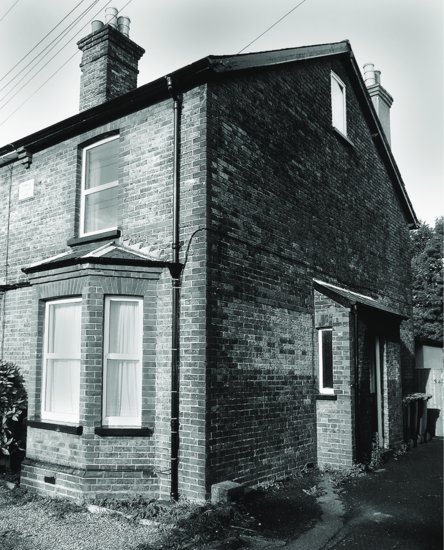

For almost twenty years, 34 Miles Road, Epsom, was home to James Patrick Page.

DAVID WILLIAMS That small front room at Jim's house became the center of our world. Jim must have had equally tolerant neighbors, for we did make a racket in that tiny space…. We started to buy the Melody Maker … and soon found that there were a few more interesting examples of the new music available than those [that] made the hit parade and the radio.

CHRIS DREJA I first met Jimmy outside the Tolworth Arcade with a rare goldfish in a plastic bag. He was very sweet. You could relate to him immediately. Eric Clapton was hiding secrets, so he tended to be a bit more of an enigmatic personality, but Jimmy was a very well-adjusted young kid from round our way and had all the right credentials. He adored his mother but wasn't so fond of his father, as I understood it from various conversations I had.

DAVID WILLIAMS Apart from his brief flirtation with skiffle, Jim had not really reached the stage where he was playing with other musicians, and it was about this time that he made his first solo appearance on a children's television talent show called All Your Own. I reckon his mother must have been instrumental in setting it up.

MARILYN COLE Even at thirteen, in that famous TV clip, Jimmy had a determination about him. He talked eloquently to Huw Wheldon. I thought he stood out even then—sure of himself, ambitious.

UNITY MacLEAN (manager of Swan Song's London office, 1976–1980) Jimmy was small and feminine and a little bit of a crybaby from time to time. Very, very creative and very inquisitive. He wanted to explore every sound and every instrument and every nuance of music, largely because he was brought up as an only child and his mother was a bit of a social climber. He was always looking for another high to stimulate his interest, hence the interest in black magic.

JIMMY PAGE My interest in the occult started when I was about fifteen.

GLYN JOHNS I don't know that Jimmy was ever angelic, though he was always as tight as a duck's ass. I bet he's got the first two bob his mum ever gave him.

JIMMY PAGE The record that made me want to play guitar was “Baby, Let's Play House” by Presley. I just heard two guitars and a bass and thought, “Yeah, that's it.” I want to be part of this.

MICHAEL DES BARRES (lead singer of Swan Song band Detective) Jimmy is epitomized in that scene in the It Might Get Loud documentary where he's listening to Link Wray's “Rumble,” and he's a child, and he's so excited and enthralled by the magic of that record.

JEFF BECK (Eric Clapton's replacement in the Yardbirds) [My sister] was just getting settled into—where was it?—Epsom Art School, and she came back and said, “There was a bloke at school with a funny-shaped guitar like yours.” I went, “Where is he? Take me to him!” She said, “I'll fix it up. His name's Jim, Jimmy Page.” I couldn't believe that there was another human being in Surrey interested in strange-shaped solid guitars. We came on the bus, and [Jimmy] played for us. [He] played “Not Fade Away.” I never forgot it.

JIMMY PAGE It was more like, “Can you play Ricky Nelson's ‘My Babe'?” And we'd both have a go at trying to play the solo, because that was the key James Burton solo.

JOHN PAUL JONES I was an only child. A spoiled brat. It's interesting because I was reading something about only children, and you have a different view on life. It comes out of a certain insecurity.

I had a ukulele banjo, a little one, and I had that strung up like a bass. Actually, my father, because I was very young, had to sign a guarantee, and he said to me, “Don't bother with a bass guitar. Take up the tenor saxophone. It'll take two years, and the bass guitar will never be heard of again.” But I really wanted a bass guitar.

CHRIS WELCH We were torn between skiffle and rock 'n' roll. But in our eyes, it was all wonderful music that we liked for different reasons. We went to see the famous rock 'n' roll movies, and there was all that excitement.

JOHN PAUL JONES My dad bought a record player and let me go out and buy records by Jerry Lee Lewis and the Everly Brothers, Little Richard, Ray Charles. Ray Charles got me into organs. I listened to a lot of Jimmy Smith in those days, but my dad didn't like Jimmy Smith: “Nothing to it, just running up and down the keyboard!”

ROY CARR (writer for New Musical Express from the '60s to the '80s) It was all matching-tie-and-hanky and Hank Marvin. When Johnny Kidd and the Pirates came along, they offered a different take on it all. In their own way, they were quite threatening.

CLEM CATTINI (leading drummer on London session scene of the '60s) It became a sort of turn from skiffle to rock 'n' roll, basically. I was touring with Johnny Kidd and the Pirates. We used to play this place in Aylesbury, and Jimmy was in Neil Christian and the Crusaders, which was the support band. He was only fifteen, and he was already a phenomenal player.

JOHN PAUL JONES I remember him having a reputation almost before I turned professional, when he was with Neil Christian and the Crusaders. It was always, “You've got to hear this guy.”

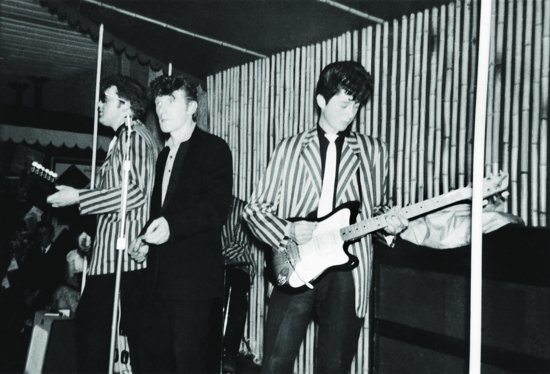

Page playing with Red E. Lewis and the Redcaps, 1960. Left to right: John “Jumbo” Spicer, Red E. Lewis, and Little Jim on the Grazioso. (Courtesy of David Williams/Music Mentor Books)

JIMMY PAGE This was before the Stones happened, so we were doing Chuck Berry, Gene Vincent, and Bo Diddley things, mainly. At the time, public taste was more engineered toward Top 10 records, so it was a bit of a struggle. But there'd always be a small section of the audience into what we were doing.

CHRIS WELCH We learned about the roots of rock 'n' roll through people like Chris Barber and Alexis Korner.

KEITH ALTHAM As trad jazz got a bit tired, there were little breakaways by people like Chris Barber, who really was the godfather figure of British blues. And the father was obviously Alexis Korner, who I saw with Cyril Davies at the Thames Hotel in Hampton Court.

BILL WYMAN (bass guitarist with the Rolling Stones) By providing a base first for skiffle and then for the blues, Chris was virtually a founding father of what came next—a British rock scene.

JEFF BECK The thing that shook me was an EP by Muddy Waters…. One of the tracks was “You Shook Me,” which both Led Zeppelin and I ripped off on our first albums.

JIMMY PAGE There were guitarists who could play really well acoustic, but they couldn't make that transition. It just didn't work on electric for them. But Muddy managed to come up with this style that really crystallized his whole thing. As a kid, as a teenager listening to that music, I was really just shaken to the core by it.

GLYN JOHNS I had a band I managed called the Presidents, and the bass player Colin Goulding knew Jimmy. Colin and I were in a coffee shop on Cheam High Street, and Ian Stewart went by on his bicycle. Colin said, “See that guy there? He's got the most amazing collection of blues records.” So I sought Ian out. He told me he was putting this band together with a guy called Brian Jones.

JEFF BECK Stu was definitely the cornerstone of that Surrey-Richmond thing. He was Mr. Blues. He made you feel guilty about liking any other kind of music.

GLYN JOHNS When I heard the Stones, it was like whoopee time. Popular music of the day was pretty banal and pretty naff, so we were all a bit frustrated. I remember this guy up the road played me a Snooks Eaglin record, and it was so raw and rough and gutsy. There was nothing prissy about it.

LONG JOHN BALDRY (singer with Blues Incorporated and other '60s R&B groups in London) We thought of blues as being strictly acoustic music, and Muddy came over to Britain with this electric guitar and a big amplifier, and a lot of people said, “Ooh, sacrilegious, dreadful, dreadful, he's selling out the blues,” and all that. But Cyril Davies, Alexis Korner, and I looked at this and thought, “Hmm, this is interesting,” and we started trying it ourselves.

JOHN RENBOURN (folk guitarist on Kingston scene and founder member of Pentangle) The R&B craze had replaced skiffle, and the best band was considered to be Blues Incorporated.

ALEXIS KORNER (singer-guitarist with Blues Incorporated) Blues Incorporated was basically a reaction against trad. Most of us had been through trad jazz, and for various reasons we wanted to play something that was the complete antithesis of trad jazz, which by then had got very finicky and very kitsch altogether. You couldn't have found anything more fundamentally opposed to the concept of trad jazz than Muddy Waters.

BILL COLE (bass player in skiffle and R&B era) Alexis had a band [at Studio 51 in Soho]—a sort of mainstay band that included the late Cyril Davies on harmonica, who sadly died of leukemia very early. But we all liked that stuff, you know—the country blues, the Delta blues, the Chicago electrified blues. We were all listening to that stuff long before the general members of the public. None of us could have foreseen that it would take off in the way that it has done today. I used to sit in with [the Rolling Stones] at the 51 Club. They were the Sunday afternoon group.

BILL WYMAN On March 3rd, 1963, we played … an afternoon session at Studio 51. It was ironic that we were given a great welcome by the ladies, Vi and Pat, who ran this stronghold of New Orleans style jazz—whereas the jazz snobs at the Marquee and elsewhere saw us as upstarts who should not be encouraged.

KEITH RICHARDS (guitarist with the Rolling Stones) At this time, there was a huge strain between what we were doing and traditional jazz, which basically represented the whole London club scene. All the clubs and pubs were locked up within a few promoters' hands, and suddenly I guess they felt the chill winter coming in and realized there would be no more “Midnight in Moscow” or “Petite Fleur” for them.

CHRIS DREJA It started to happen because we all had a lot to do with Alexis and Cyril and Blues Incorporated. It was a time when we had the absolutely ridiculous idea that we could play music and form bands. We were looking for venues, and the Melody Maker had little ads in the back, and that was another way we used to communicate. You started to get promoters who had places, and then you realized that people were paying and kids were coming to hear blues, much more so than trad jazz. We knew about Alexis because the Stones played the Ealing club, which was a pivotal hole-in-the-ground in 1962.

JIMMY PAGE When I was still at school, the amount of records about was so thin on the ground. One of your pals would be a rock collector, another would be a blues collector. Then this rumor went round on the grapevine that one of the guys had actually found a girl who liked Howlin' Wolf.

CHRIS DREJA You had to go to this import shop in Streatham. It was a fucking long journey, and in the winter we all got chilblains because it was damp and horrible, and the buses were open with no doors. It was a hard blues life!

MARTIN STONE (blues guitarist and friend of Page's) Dave Kelly's Swing Shop was a pretty important psychogeographical landmark in the blues boom. The South London blues mafia congregated there, and Dave worked behind the counter on Saturdays. It was one of the only places you could buy American blues records. Eric Clapton bought Freddie King Sings there, and I later stole it from his girlfriend.

CHRIS DREJA Communication was very difficult. You often saw people on the platform of the station with a record, and then there was the slow grapevine of the arts school system. L' Auberge, the coffee shop in Richmond, was where we all hung out. In Café Nero, you've got twenty million choices, but in those days you had two. And as a down-and-out student or musician, you could make that coffee last four hours. All of us—Eric, myself, other players—started to drift there. These were very gentle days. The furthest-out you got were suede shoes.

CHRIS WELCH The original Jazz & Blues Festival in 1961 was how I became aware of all this going on in Richmond. But the crucial year was 1963. I managed to get tickets as a reporter for the Bexleyheath and Welling Observer, and we were all watching Acker Bilk when an announcement came over the P.A. that the Rolling Stones were playing in the tent across the field. The whole audience turned round and ran toward this tent. We were all stuck in this marquee, and they were quite aggressive, and it was like seeing the Sex Pistols years later.

JIMMY PAGE I came across Mick and Keith, curiously enough, on a pilgrimage to see the Folk Festival of the Blues in Manchester. We all went up in a van, all the guys from the Epsom area and the record collectors. I remember them vividly, because Keith said he played guitar and Mick said he played harp.

MARIE DIXON (widow of Chess Records legend Willie Dixon) Willie went over to Europe because he felt like the blues was dying in the United States. He said to me, “I'm going overseas to see if I can't drum up some more business for my music.” He wanted to make the blues more widespread in England and Europe. He had no problem with these young skinny English boys learning his music.

CHRIS DREJA The Stones came down the grapevine pretty fast. On a Friday or Saturday night, Top Topham and I used to go the Station Hotel in Richmond, and at the back they had a hall that was crammed. Seeing the Stones a couple of times made Top and I even more obsessive about doing our own band.

JIMMY PAGE I was involved in the old Richmond and Eel Pie Island sets—well, I used to play at those jazz clubs where the Kinks played, and I'd always been in groups around the Kingston area. Kingston and Richmond were the two key places, really, but by that time I was well into the Marquee. It was a good scene then, because everyone had this same upbringing and had been locked away with their records, and there was something really new to offer. It just exploded from there.

ROY CARR I used to buy import Chess albums from Impulse on New Oxford Street. I remember going in one day to pick up something, and Brian Jones was looking at it and wanted it. The guy said, “I'm sorry, it's already sold to this gentleman.” And I went down to the Marquee that night, and it was one of the Stones' first gigs there. Brian was very sullen when he saw me.

JIMMY PAGE Cyril Davies, who had just broken away from Alexis Korner and was the one who turned everybody on to the electric harmonica, asked me to join his band [and] I did in fact play with them a bit, and the band was basically the nucleus of Screaming Lord Sutch's band. I think Neil Christian felt I wanted to go with Cyril Davies, but I was being perfectly honest in telling him that I couldn't carry on—I couldn't understand why I was getting ill all the time.

LORI MATTIX (L.A. groupie and principal Page squeeze in America, 1973–1974) Jimmy went to art school and dropped out. He told me that he started in art school and then decided he wanted to become a session musician.

CHRIS DREJA One of the great things the British government did was start this arts stream for selective children—and it wasn't hard to get in. Kingston was terribly relaxed, run by a guy called Dyson and a younger arts master whom we completely wrapped around our finger. It all came out of that art school semi-intelligentsia—that's where the Southern blues thing kicked off. I mean, we weren't that intelligent, but we were given a chance in that system.

MARTIN STONE I was playing in a Shadows-type band, like most guitarists, but when you listened to R&B records, you would hear this guitar that was not like Bert Weedon. It was overloaded, there was sustain on it. It had what Jake Riviera calls “the fuck beat.” And I leaped on it. It was like, “Now I've got this thing, and you don't know what it is.”

CHRIS DREJA Eric Clapton used to turn up at L' Auberge with a guitar and long thumbnails; he was very Robert Johnson. He jumped at the Yardbirds because he came to a rehearsal and saw that we were attempting to play the music that he was obsessed with. He wasn't God then. He was just the only guy we knew.

CHRIS WELCH The very first band I was asked to interview when I started at Melody Maker in 1964 was the Yardbirds. We went out to a coffee bar in Fleet Street called the Kardoma. They seemed like the most exciting rock band around—much more wired-up than the Stones, who were looser. It was frantic nervous energy, like schoolboys going mad.

GEOFF GRIMES (plugger for Atlantic Records U.K., 1972–1978) There was a series of clubs we all used to go to: the Ricky Tick, the Marquee, the Scene. We'd spend almost two days completely out of it—the evening session, the late night, then we'd sleep somewhere and get up and do it all again. And in among this, the Crawdaddy opened, and the first band we saw there was the Stones. Then, when it moved to a better ground across the road, we met the Yardbirds. I saw all the guitarists in the Yardbirds: Eric Clapton first of all, and I was there when Jeff Beck played. I used to go every Sunday to the Crawdaddy. It was a religion. You had to go.

JOHN PAUL JONES There was this whole little white R&B movement [that] grew up quite separately and would evolve into the Stones and the Yardbirds…. They were all into Chuck Berry and the Chess people—blues twits, really. As a musical scene, they just didn't rate, really.

None of those people did: the Yardbirds, it was like, “Oh dear,” it was more punk than R&B. Oh, it was great for that, but when you heard them play “Little Red Rooster,” you'd go, “Oh, no, please don't.”