5

Happenings Fifty Years' Time Ago

The English, I think, have always had a better idea of the multi-voiced nature of performance than Americans. They were able to view the blues as theatre, which it was and still is.

—Mike Spies, slate.com, March 2011

CHRIS DREJA (bassist with Page's pre-Zeppelin band the Yardbirds) When Eric Clapton left the Yardbirds, I was upset because—being a junior member—I didn't really have a decision in that. He did us a favor, ironically, because he'd become very blinkered at that point, in terms of music. I was sorry to see him go as a friend, but there was no more “I'm not doing that,” and we now became totally free to be eclectic with Jeff Beck.

SIMON NAPIER-BELL (second manager of the Yardbirds) Paul Samwell-Smith left, and Jeff said, “I want Jimmy Page in the group.” I didn't know much about rock musicians, but I had enough instinct to know it was a crazy idea. I told Jeff, “You're the genius guitarist in the group; to bring in someone as good as you is crazy.” But Beck absolutely insisted—and besides, Page would supposedly be playing bass.

BIG JIM SULLIVAN (leading London session guitarist in the '60s) Jim and I talked quite a bit when he was trying out for the Yardbirds. I think he was quite happy to get out of the session world. I wouldn't give up sessions at that moment. I thought, “I've got two cars, I've got a gardener, who needs any more than that?” I suppose it was a risk to start a band.

JIMMY PAGE (speaking in 1966) I was drying up as a guitarist. I played a lot of rhythm guitar, which was very dull and left me no time to practice. Most of the musicians I know think I did the right thing in joining the Yardbirds. I want to contribute a great deal more to the Yardbirds than just standing there looking glum. Just because you play bass does not mean you have no presence.

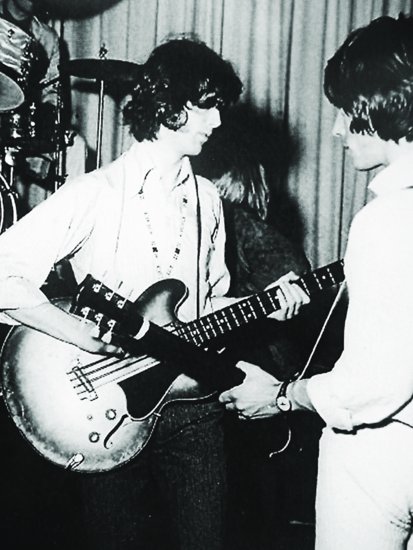

Page on bass in the Yardbirds, with Jeff Beck, June 1966. (Howard Mylett collection)

JEFF BECK Jimmy was not a bass player, as we all know. But the only way I could get him involved was by insisting it would be okay for him to take over on bass. And gradually—within a week, I think—we were talking about doing dueling guitar leads. We switched Chris Dreja onto bass in order to get Jimmy on guitar.

JIMMY PAGE We had to play this gig in San Francisco—at the Carousel Ballroom, I believe—and Jeff couldn't make it. So I took over lead that night, and Chris played bass. It was really nerve-racking because this was at the height of the Yardbirds' reputation, and I wasn't exactly ready to roar off on lead guitar. But it went off all right, and after that we stayed that way—so when Jeff recovered, it was two lead guitars from that point on.

CHRIS DREJA Jimmy and Jeff were like a couple of gunslingers, really. Jeff had been on the road more than Jimmy. He'd discovered California. He'd discovered blond women. He'd got divorced. He'd got away from his flat and was getting a reputation. He had his big ego. So it didn't really work, but it did work on “Happenings Ten Years' Time Ago.” I think we encapsulated the whole bloody scene within two and a half minutes on that song.

CHRIS WELCH (writer for Melody Maker in the '60s and '70s) I saw them at the Marquee. It was a stereo guitar duel, the two of them battling it out. I felt a bit sorry for Keith Relf, who was drowned out. It was deafening. I suppose we were witnessing the birth of hard rock.

HENRY “THE HORSE” SMITH (roadie for the Yardbirds and Zeppelin, 1966–1972) There was always something electrifying going on when Jeff and Jimmy played live together. Even though they both played bluesy guitar, they played totally different. Jeff was like the Eddie Haskell of guitar players; he was the guy saying, “Oh, hello, Mrs. Cleaver, you look very nice today,” and then he turns around and plays something back that's really snide.

Competition between Jimmy and Jeff was healthy. It wasn't a love-hate relationship, because they both respected each other. They could egg each other on a little bit and take it to the brink, but if you had to pick a winner every time, it would probably be Jeff.

JIMMY PAGE We had something that could have been really special when we were doing the dual-lead thing together. But we'd rehearse hard on certain things—working out sections where we'd play harmonies like a stereo guitar effect—and then onstage Jeff was just uncontrollable.

MICK FARREN (singer with the Deviants and writer for the underground press) The Yardbirds didn't make any sense at all. You'd go and see them, and they'd be playing blues, and then they'd come out with “Over Under Sideways Down.” Keith Relf was so kind of transparent that you couldn't really take him seriously. So the Yardbirds were essentially a medium for guitar players.

Page wasn't really what we were going to see. He was a good lad, but I could never quite pin it down. Page back then didn't have the apparent Beck ego. Beck once walked onstage at the Roundhouse, looked at the assembled crowd, and said, “Bollocks to this”—and there was no show! I said, “What? We didn't come all this way for Arthur Brown!”

JEFF BECK Simon Napier-Bell got us Blow-Up, a real feather in his cap. “Okay, pal, you're the new manager, what've you got?” “How about three grand for doing an Antonioni movie?” I had a great time smashing up Hofner guitars for three days.

BP FALLON (U.K. press officer for Zeppelin, 1972–1976) I was an extra in Blow-Up, ten quid a day to look stoned and watch the Yardbirds. You couldn't meet Jimmy then and not be conscious that the cat was cool in the same way that Miles Davis or Serge Gainsbourg was cool. During the filming, he was sitting there being very quiet while Jeff Beck was mouthing off about what a bad singer Mick Jagger was. It was like, “Your time is gonna come …”

JIMMY PAGE When I joined the band, Jeff wasn't going to walk off anymore and stuff. Well, he did a couple of times. If he'd had a bad day, he used to take it out on the audience, which was a bit weird.

JUNE HARRIS BARSALONA (wife of talent agent Frank Barsalona) Frank and I were once in Detroit for a Yardbirds show, and we're waiting for Jeff to come on at the Grande Ballroom, and suddenly we're told that he is not going on—he's going home, or at least back to Mary Hughes in California. It was hysterical at the time. Jeff couldn't take the success.

JEFF BECK I went back to L.A. and hung around there by the pool for a while and then went home, expecting the Yardbirds to fold, but Page was on form, and people started freaking over him, so they were alright.

CHRIS DREJA Jimmy wanted it to succeed, and when we pulled off that Dick Clark tour, it was him saying, “Let's go on as a four-piece.” He was the only one who wanted to go on in that form. He liked the life, and he had all sorts of advantages and not just musically. He had the freaks that he liked.

RICHARD COLE (road manager for the Yardbirds and Led Zeppelin) The Yardbirds knew all the groupies in New York, and all the groupies knew them. These were the core American girls—Devon, Emeretta, and a few more we can't mention since they're happily married now to famous rock stars. They knew the bands' itineraries as well as I did, God knows how.

I'd been to L.A., but I'd never met these girls that the Yardbirds knew. We would go up to Frank Zappa's house, the old Tom Mix cabin, and Captain Beefheart would come round. Those girls were known as groupies, but they were nothing in comparison to what came later.

JIMMY PAGE Simon Napier-Bell called up with the news that he was selling his stake in the Yardbirds to Mickie Most. I think they must have cooked it up, actually, the three of them: Napier-Bell, Most, and Beck. This way Beck could have a solo career, which he had already begun in a way with the recording of “Beck's Bolero.”

MICKIE MOST (record producer and partner with Peter Grant in RAK Management) Jeff decided halfway through a tour that he didn't want to be in the Yardbirds anymore. For fifteen minutes, he wanted to be a pop star. And he came back from Los Angeles in pop star gear. I'd just come back from New York, and I had this song called “Hi Ho Silver Lining” and I played it to him. And the next thing we know, we were in the studio and it was a hit. John Paul Jones did those lovely cello arrangements.

ANDY JOHNS (engineer on Led Zeppelin II, III, and the untitled fourth album) John Paul was a trained, studied sight reader. He was as quick as greased lightning. I used to have a deal with him where I would polish his Fender Jazz bass and say, “Seeing as I've polished your bass, could you show me how that goes?” And he would.

He said to me, “I'm tired of doing these sessions.” So I got him a Corn Flakes ad, and he went, “Thanks a fucking lot! Kellogg's Corn Flakes!” He was going to be an arranger, or he was going to join a band. He did the arrangements for the Stones on Their Satanic Majesties Request. He said, “I'm going to make so much money in the next two or three years, you're not even going to recognize me.” I said, “Yeah, right.” Sure enough, within two years he'd made a million pounds.

• • •

MALCOLM McLAREN (manager of the Sex Pistols) Peter Grant was an extraordinary underling, a character who came from the back streets of London and sought to change his life. And entering into the world of rock 'n' roll was the best way to do that.

PETER GRANT (manager of the Yardbirds, the Jeff Beck Group, and Led Zeppelin) I'm proud of myself —especially for my dear old mum. I mean, I was born illegitimate, and in the late '30s that must have been horrendous. I never knew my father, and I'm proud for my mum and for my own children that I've done what I did.

GLORIA GRANT (ex-wife of Peter Grant) Peter always clammed up about his childhood. He would say, “Well, I'm an illegitimate child, end of subject.” He never once said, “I want to find out more about my dad.” Probably his mother never said much to him either, and I didn't feel I could ask her myself. I think he was upset about it, really, and yet in another way he was cross about it. But we don't know the full story. Things were completely different in 1935. The only thing he ever told me was that his dad's surname was Underwood, though I don't think he was even completely certain about that.

HELEN GRANT (daughter of Peter Grant) Dad's way of dealing with those sort of things would be to just shut them out, really. You know, he wouldn't want to think about anything like that.

PHIL CARSON (head of Atlantic Records U.K. and close confidant of Zeppelin's) Peter and I grew up in a very similar area of south London. I went to St. Joseph's College, which was the Catholic school for the sons of gentlemen, whereas Peter went to Ingram Road School. You can tell from the name that the school is going to be rough and tough. And we laughed about it, because there was a lot of jealousy between the two schools.

One day there was an inter-school fight arranged on Streatham Common, and the boys from our 1st XI football team showed up with about six fifteen-year-olds from Ingram Road, who proceeded to beat the shit out of them. Apparently, Peter was one of the six or seven.

MALCOLM McLAREN He was the guy who hung around fairgrounds in the '50s, because that's where all gypsies and outlaws hung.

PETER GRANT All I know is that if I hadn't been a fucking stagehand at the Croydon Empire for 15 bob a show, and if I hadn't done all the things I have—like being a film extra and on the road with Gene Vincent and the rest—there's no way I could have coped with the events of the past five or six years.

KEITH ALTHAM (writer for NME, Record Mirror, and other publications) The first time I ever ran into Peter was at the Flamingo on Wardour Street, and he was on the door. He was an ex-wrestler who'd come up through Paul Lincoln at the 2i's club. My first close encounter, though, was when I was on Teen magazine, and he was taking Gene Vincent on tour.

We're on the coach with them, going to a doubleheader in Aylesbury, and Peter's main task is to stop Gene [from] drinking. After the first gig, Peter's having a little trouble negotiating the money outside the coach, and suddenly there's this banging noise coming from inside the coach. Gene's got hold of his wife by the hair and is thumping her head against the window. So Peter jumps on the coach and comes down and separates them with the words, “Listen, I'm trying to sort out the fuckin' readies!” He goes back out, and it starts up again. Except this time, it's the wife who's banging Gene's head against the window.

Before the second show, Gene decides it would be a good idea to down half a bottle of vodka. And he stands up and slips, and his good leg gets wedged between an upright bar and one of the seats. So Peter wanders down like Samson, gets hold of the bar, and pulls it apart so he can extract the leg, which has swollen horribly, so that Gene can barely stand and may not be able to do the show.

It transpires Peter has worked out that as long as Gene is onstage when the curtain opens, he'll get the money. So the curtains open, and Peter has inserted a microphone stand through Gene's leather jacket to hold him upright. We hear the opening bars of “Be Bop a-Lula,” and Gene falls forward flat on his face. Peter walks on and carries him off like a pig on a spit. And he gets the money.

MICKIE MOST He always made sure a contract was honored … and he had a very good head for figures.

KEITH ALTHAM Peter was sufficiently savvy to pick up the percentages, and the profits added up. He was not what I would call an intelligent man, but he'd picked up the rudiments of the music business, and he was a formidable figure to deal with in terms of his physical presence and also in terms of his attitude. He wasn't scared of anybody.

GLORIA GRANT In late 1961, I was in a singing act with my sisters Sue and Jean, and we were working for the Noel Gay agency. There was a tour coming up where we'd be working for Cadet cigarettes. So we went to rehearsals in Denmark Street, and this man came in to talk about the show we were going to do. It was Peter, and we sort of said hello to each other.

It transpired that he had a big van, and the agency wanted him to drive us around the miners' clubs in South Wales. It was a really good show, and we all got on well together, all of us staying in digs. Peter even joined in when we sang “We'll Keep a Welcome in the Hillside”—though he couldn't hold a tune to save his life.

He would often say to the three of us, “I'll be your manager.” And I'd say, “How do you know how to manage anybody?” By the end of the tour, which was about March or April of 1962, we were engaged to be married. We didn't have much money, but we had a lot of laughs. We moved in with his mum in South Norwood. Dorothy wasn't quite ready for me. She was very Victorian in her ways, and I wasn't. I was twenty-three, and I'd been working in the theater since I was eighteen. We didn't quite gel, but we got on alright. There were times when Peter had to stick up for me.

Then I found out I was pregnant with Helen, so we rented a little flat a bit farther up the hill at Dorrington Court, and that's when Peter started working for Don Arden.

ED BICKNELL (former manager of Dire Straits and friend of Peter Grant's) I think Don gave him £50 a week, out of which he had to pay for the petrol. Through that, he started driving for the other tours Don was promoting, like Little Richard and Bo Diddley. Famously, Don called Peter into his office one day and said, “I want you to go to America and get Chuck Berry.”

ALAN CALLAN (president of Swan Song in the U.K., 1977–1979) Don Arden thought the artists worked for him, and Peter thought he worked for the artists. I think what really brought that about was Peter's involvement with Chuck Berry. He went to America to try and bring Chuck to England, and I believe Chuck drove him from the airport to the Chess offices. Peter couldn't believe that Chuck was actually his chauffeur. [Peter] asked him how many records he'd sold, and Chuck said, “I don't know.” And Peter thought, “My God, this is wrong.”

ROY CARR (writer for New Musical Express) Don Arden was an asshole. He thought he was Al Capone. He was just a working-class Jewish boy who got it into his brain that he wanted to be Edward G. Robinson.

ED BICKNELL Occasionally, Peter would be dispatched by Don to sort out an irksome issue, like Robert Stigwood trying to steal a band from him. I once asked Peter if it was true he'd dangled Stiggy out of a window by his ankles. He said, “No, I merely introduced him to the view.”

LAURENCE MYERS (music-business accountant and partner in RAK Records) I think the Don Arden effect—“I am the Don, I am a gangster”—impressed Peter to the point where he used his physicality in the same way: “I'm a big guy, and you don't want to fuck with me.” But I never actually heard of him hitting anybody.

MICKIE MOST I admit, we did use a bit of the old-fashioned scare tactics. But nobody had any guns. It was handbags at ten paces, really. I don't think Peter was involved with gangsters. He was a sweetheart, really. All that stuff about being a muscle man and beating people up … it was all nonsense, really. It was more bravado.

ROY CARR I knew Peter as someone you'd see up at the bar in the Marquee or round the drinking clubs. He was massive, and he had that sort of Fu Manchu facial hair.

CHRIS DREJA Mickie Most was a very polite guy, and then there was this monster of a man who sat opposite him who looked like he could crush you with one hand.

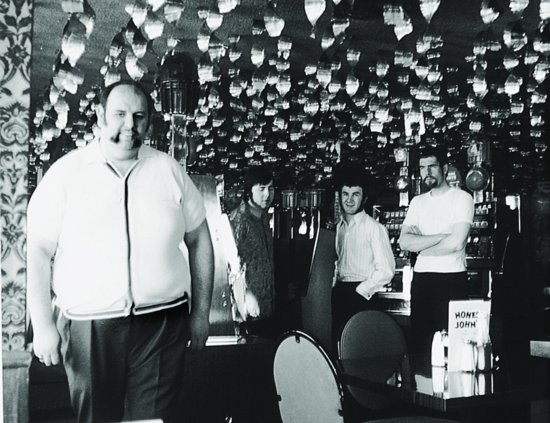

Peter Grant in America with the New Vaudeville Band, May 1967. (Richard Cole Collection)

LAURENCE MYERS My first impression of Peter was of this huge mountain of a man, clearly not educated and definitely conscious of it. You'd be in meetings, and you could feel that he was uncomfortable if people started to talk about anything cultured or about world affairs. It didn't occur to me that he could run a management company successfully, just because of his background. But his practical knowledge was immense, as was his knowledge of dealing with bands.

GLORIA GRANT Don and Peter were very similar in their makeup, and Peter learned from him by being with him all the time. Peter would come back with these extraordinary tales of being on the road with Little Richard and Bo Diddley. There was always plenty to talk about.

RICHARD COLE I think Gloria was quite in awe of Peter, and he could always make her laugh.

LAURENCE MYERS My first-ever meeting in the music business, after I'd first got Mickie Most as a client, was with Don Arden. The Animals were managed at the time by Mike Jeffrey, and they were driving him mad that they hadn't been paid about six and a half thousand pounds for a tour Don had organized, and that Peter had been the road manager on. Mickie said, “Don't worry, I'll get the money out of Don.” So I got the accounting together, put on my best suit, and the three of us went over to Don's offices on Hay Hill.

We're sitting in reception, and I can hear through the doorway this voice ranting and raving, saying, “Listen, you Christian schmuck, are you fucking mad?!” And then the phone is slammed down. So we go into the office, and Don is sitting there, beaming. Mickie starts in on him and bangs the desk. Peter stands up, towers over Don, and says, “Listen, you asshole, pay up!!” I then try to make my mark in the world by saying, “Gentlemen, gentlemen, let me handle this.”

Don goes, “Who the fuck are you?” I said I was a chartered accountant and that I was authorized by the Animals to speak on their behalf, and I brought out my beautifully produced piece of paper showing that he owed them whatever it was. I said, “Are you going to pay them?” And he said, “No.” I said, “Oh.”

Peter starts banging the desk and says, “I'm going to turn this desk over, Don.” I start up again in a very smug voice: “Will you please let me deal with this? Mr. Arden, do you know what will happen if you don't pay this? We will issue a writ against you.” Don goes, “Will you?” He opens a drawer full of writs, takes them out, and chucks them out the window. He goes, “Listen, you putz, if you don't get out of my office, you're gonna follow them out the window.” At which point Peter starts bouncing the desk up and down, and eventually we walk out. I don't think the Animals ever got paid.

HARVEY LISBERG (manager of Herman's Hermits) Mickie and Peter were a bit of a comedy act, a bit like Laurel and Hardy. Mickie was a very strong character, very opinionated, had an answer for everything. Peter was a sweetie, really, nothing like the way he looked.

HELEN GRANT The good thing about Dad and Mickie was that they saw each other outside of the work thing. We used to see Mickie in the south of France a lot. We used to go to Monaco, to the Grand Prix. Dad always spoke very highly of Mickie.

LAURENCE MYERS We decided to set up three companies under the RAK umbrella: records, publishing, and management. There were three desks. Mickie's brother Dave looked after publishing, so he was at one desk. Then there was Mickie, who looked after records, and then Peter, who was going to run the management side. I had a client named Geoff Stephens, who'd written and produced a record called “Winchester Cathedral.” The record became a huge hit, and we put together the New Vaudeville Band to go on Top of the Pops. I said, “Let's get Peter to manage them.” That was RAK Management's first-ever client.

GLORIA GRANT Helen came up to me one morning at our house in Shepherd's Bush and said, “Mummy, there's a man at the door in a long black coat.” I went to the door, and it was Richard Cole. I can still see him in that long black sort of Crombie coat. He was a real Jack-the-lad.

RICHARD COLE In the middle of 1966, I was driving back from Nottingham with Keith Moon and John Entwistle, and this record called “Winchester Cathedral” comes on the radio. Moonie says, “What the fuck is that old piece of shit?” And what happened was that Geoff Stephens, who'd made the record, approached Peter and said, “Look, the record is No. 1 all over the place, but there's no band. Can you put a band together for me?”

I was recommended as tour manager for the New Vaudeville Band, so I went to see Peter in their new office at 155 Oxford Street. In those days, Peter managed Ray Cameron—Michael McIntyre's dad—and a girl trio called the She-Trinity. And then came the New Vaudeville Band. I said to Peter, “I want thirty pounds a week, take it or leave it.” Years later, he told me, “I thought, if you're that cheeky to me, you'll be alright getting the money off those promoters.” He also said, “If I hear you've been telling tales out of this office, I'll bite yer fuckin' ears off.”

MARK LONDON (comanager with Peter Grant of Stone the Crows and Maggie Bell) I first met Peter in 1965, when he and Mickie already had the office on Oxford Street. Then I got into management with Peter when we set up a company called Colour Me Gone. I said I'd go look for acts, and we'd manage them together. I took a band called Cartoone to Ahmet Ertegun and Jerry Wexler, and they liked it, and we did two albums for Atlantic. I hired Les Harvey to play guitar with them, and I said I'd come back and look at Power, the band Les had with Maggie Bell in Glasgow. Peter and I went up to see them, and he renamed them Stone the Crows.

155 Oxford Street, London: RAK's offices were on the top floor. (Art Sperl)

MAGGIE BELL (singer with Stone the Crows and Swan Song solo artist) 155 Oxford Street had a tiny little lift that only took two people or one Peter Grant. I used to take the chance and get in there with him. They would all be in that office at one time, and there was standing room only because you couldn't sit down anywhere.

RICHARD COLE Mickie sat on the right-hand side behind a big desk, and Peter sat on the left-hand side behind a big desk. There were no seats, so you had to stand up when you talked to them. And while you were talking to one of them, the other would be making V-signs behind your back. Mickie was always dressed impeccably—as were his wife and son, who would come in on a Friday afternoon because they were flying down to Cannes, where Mickie kept his yacht.

JOHN PAUL JONES [The office] was like fifty-foot long, and Peter was up one end and Mickie was down the other. I was the musical director for Mickie, so that was how I met Peter. He was a very sensitive man. He was a very, very smart man. People just think of his size and his reputation, but actually he never had to use his size. He could out-talk anybody.