6

Turning to Gold

I'd been an apprentice for years, and I'd discovered something that someone like Mickie didn't have a clue even existed.

—Jimmy Page to Nick Kent, 1973

JIMMY PAGE Peter was working with Mickie and was offered the [Yardbirds'] management when Most was offered the recording. I'd known Peter from way back in the days of Immediate [Records] because our offices were next door to Mickie, and Peter was working for him. The first thing we did with Peter was a tour of Australia, and we found that suddenly there was some money being made after all this time.

CHRIS DREJA (bassist with the Yardbirds) The last year, when Peter was with the band, was the only year we ever made any money. He dealt with very stroppy promoters and started to turn the tables on them. He fought. It was through Peter I learned that if you want to make money on tour in America, don't order room service—it all gets charged to your account.

JEFF BECK I was beginning to think about forgetting it all. Then Peter Grant saw that there was more in it and, rather than lose the whole thing, said he'd fix up an American tour [for the Jeff Beck Group], and that was just the one thread left that we were hanging onto. Anyway, we made it to New York and blew the town apart completely, smashed it wide open with one performance, and we had an identity as a band right there, and that cemented it all for eighteen months.

ED BICKNELL (former manager of Dire Straits) Up until the mid-'60s, the music business people were the tail end of the variety industry. They were either gay blokes or hard-nosed East End geezers. Then came the first wave of people who'd got degrees, people like Chris Wright and Terry Ellis of Chrysalis, who were at Manchester and Newcastle, respectively. There was a shift away from people who thought in terms of variety and, most important, a shift away from people who thought pop music was going to be over in two years. Although Peter was not an educated man in the academic sense, he was moving away from the Don Arden approach toward the idea that the act was everything and that everything flowed from that. He was quite passionate about that.

CHRIS DREJA I think Mickie and Peter were both very lucky to have the Yardbirds, because we gave both of them kudos and credibility, plus some real serious practical experience.

ANNI IVIL (press officer with Atlantic U.K., late '60s–early '70s) Peter realized that you had to tour in America. Frank Barsalona at Premier Talent knew that that was how to break a group. To me, Frank was rock 'n' roll. He was absolutely the first guy who really saw what the underground was going to become.

FRANK BARSALONA (founder of Premier Talent agency, speaking in 1974) I realized that all these people I'd thought so much of were pretty stupid, and the way they wanted to handle my acts was pretty stupid. I wanted to guide their careers, rather than exploit their success…. I realized then that rock might really have potential, and I remembered all that business about all of the war babies growing up at the same time, and I decided then to start my own business.

JUNE HARRIS BARSALONA I met Frank right after I moved to New York from London in 1964. He was young, and nobody was concentrating on rock. He started something new, and I was able to help him because I knew a lot of the English acts. I had done a deal with the Mirror group to write about anything English that was happening here. I would see the bands, and he would get them.

STEVE VAN ZANDT (guitarist with Bruce Springsteen's E Street Band) Against the family's recommendation, Frank opens the first rock 'n' roll agency, called Premier Talent. He divides the country up into territories—sounds familiar, doesn't it?—and divides it up to these hungry new guys: Larry Magid in Philly, Jack Boller in Washington, Don Law up in Boston, you know, Bill Graham over there in Frisco, the Belkers in Cleveland, and Ronnie Delsener here in New York. In other words, he threw out all the old thieves and replaced them with a bunch of new young thieves.

ANNI IVIL The promoters made their money on it—everybody made money on it. As Frank used to say, “There's only one pot, and everyone's got to be paid out of it.”

LORAINE ALTERMAN BOYLE (writer for Rolling Stone and Melody Maker in the late '60s and '70s) Premier was the major rock booking agency in the country, and every big act really went through them. Frank and June's first apartment was on West 57th Street, and people would hang out there. Frank just seemed to control the whole scene.

JUNE HARRIS BARSALONA Frank said, “This is it, this is the future.” When he signed an act, he said, “No more of the belief that you're only as big as your last record. You've got to go out and perform. You've got to give them something for their money if you want longevity in this business.” So it was great for him to see how the acts developed. They looked at him as a kind of mentor, even though they were on the same level and the same plane.

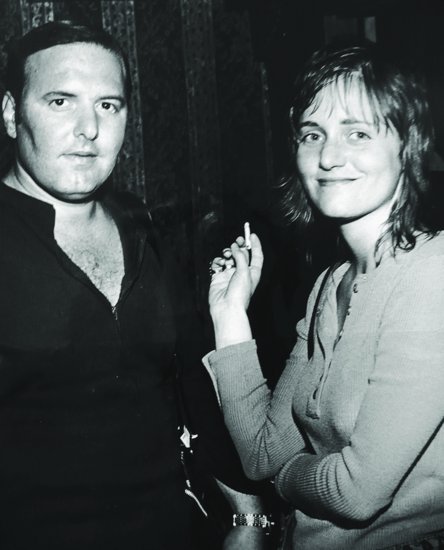

Frank Barsalona with writer Loraine Alterman, New York, 1967. (Courtesy of Loraine Alterman Boyle)

Frank would sit in his office in a pair of jeans, his feet on the desk, a shirt that probably had ink stains or spaghetti stains on it, and his Indian jewelry. When he said, “Let's go eat,” it meant bringing people back to the apartment and hanging out. I once came back from picking my mother up from the airport, and there were thirteen people in the apartment expecting dinner—four of whom were the Who.

What started out as the underground and hard rock, that's where you've got Peter with the Yardbirds and with Jeff Beck. And you've got rock stations that were beginning to form and that were only interested in contemporary rock, everything that happened at Monterey and then Woodstock. There was this peer group of people who saw what was happening in the industry and who encouraged it and were able to go along with it—who were able to go to a blues club in Chicago and know where the music was coming from and were able to talk to musicians.

SAM AIZER (artist relations man at Swan Song in the United States) People like Frank and Steve Weiss were the first ones in. Steve was a very sharp entertainment lawyer who'd had Jack Paar, and that's how he'd made his name. Once you get one successful band, you get ten bands, and all of a sudden you're important. This guy had the power that Peter didn't: he had the Rascals, Herman's Hermits, Jimi Hendrix, all these bands.

DANNY GOLDBERG (Zeppelin's U.S. press officer and subsequently president of Swan Song) Steve was a gruff tough. He was a certain type of a character that had obviously been good enough at law school and everything. He was definitely new to entertainment law and must have had a background of legitimate law, but he stumbled into rock 'n' roll and became permanently changed by it. By the time I met him, he had longish gray hair and would wear these odd clothes that were halfway between him and normal and he strutted around with a tremendous sense of himself. Always had a quick temper and flattered himself on having a quick temper. He'd been Herman's Hermits' lawyer. He knew Harvey Lisberg, who was the warmest, sweetest guy.

HARVEY LISBERG (manager of Herman's Hermits) Steve was a very charismatic figure, beautifully dressed, a ladies' man. My wife had to accompany his mistress around town, and then the next evening we're back at his home having dinner with him and his wife. It was like something out of Mad Men.

JANINE SAFER (press officer at Swan Song in the United States) Steve had two households. He did finally marry Marie, the mistress, who was one of the loveliest people you'd ever want to meet in your life—déclassé in every conceivable way, from an Italian family in Queens, a beautiful woman with dyed-blond hair and makeup three inches thick.

SHELLEY KAYE (assistant to Steve Weiss and office manager at Swan Song in the United States) I was twenty-three when I started working for Steve in 1968. I was a young kid, I didn't know anything. I walk in, and here's a guy wearing a gray pinstripe suit with a white shirt with purple flowers down the front. And I went, “Oh my gosh!” That was my introduction to the music business. Within six months to a year, I became his secretary.

RICHARD COLE (Zeppelin's road manager) Peter told me he'd been involved in a court case in America, and Steve had been the opposing lawyer and had wiped the floor with whoever Peter's lawyer was. So Peter then hired Steve, who'd done stuff for Herman's Hermits and the Young Rascals and Jimi Hendrix, a host of acts. Steve was the lawyer for Vanilla Fudge when I was their road manager. I knew their manager Phil Basile very well, and Philly was connected. Lovely guy, but you wouldn't cross him. At some conference in America—it wasn't a roast, but something like that—Joe Smith of Warner Brothers once said, “Of course, we can't forget our dear friend Steve Weiss, who's always got a kind word … and a gun.” What we heard was that Steve's dad had worked for Meyer Lansky.

JACK CALMES (cofounder of Showco sound and lighting company) Steve was the attorney for Jimi Hendrix and later for the estate. His father and family were associated and consiglieore for the mafia.

ABE HOCH (president of Swan Song, 1975–1977) There was always the intimation that Steve was connected, but we never knew what he was connected to. The thing about Peter is, when he sanctioned somebody, you basically just went along with it.

HENRY SMITH (roadie for the Yardbirds and Led Zeppelin) There was a time with the Yardbirds when we were staying at a hotel in New York, and the truck was parked out front with all the gear in it. I wake up around eight in the morning, and the truck's not in front of the door. I panic and call Barry Jay Reiss, Steve's right-hand man, and tell him the truck is missing with all of the gear in it. Before noontime, the truck is returned with all the gear. That shows you the power of Steve Weiss.

BARRY JAY REISS (attorney who worked with Zeppelin's U.S. lawyer Steve Weiss) Steve had a reputation as a very, very tough and vigorous negotiator. He was a real fighter. Sometimes he was a violent person, in the sense that a lot of telephones got yelled into. But he was also a wonderful teacher and mentor. After we worked with Lulu, who had a U.S. tax problem that we sorted out, we wound up representing quite a number of British artists in that period. Then the managers for Jimi Hendrix found us, so we started working with him. The first time Steve and I saw Jimi was at a high school gym out in Queens or on Long Island. The first twenty minutes, the kids had no idea what they were looking at. By the time he'd finished, they were on their feet.

SHELLEY KAYE The first rock concert I went to was Hendrix, which Steve promoted with Ron Delsener. I mean, I was a very conservative little girl from Brooklyn, I didn't know about any of this stuff. I was amazed by it, and it changed my whole life.

BARRY JAY REISS (lawyer and associate of Steve Weiss) It was a very exciting time. Music was king. It was a whole new industry. When I went to law school, we didn't have any courses in entertainment law. We were really inventing as we went along.

SHELLEY KAYE Everything was turning to gold. There were so many phenomenally talented artists around. It seemed that all you needed to do was come from the U.K. to America, and you'd get a record deal. I was and still am a real Anglophile, so I just thought it was fantastic. It was important to know the British terms; otherwise, you wouldn't know what people were talking about. I had no idea what a “loo” was.

EDDIE KRAMER (engineer on Led Zeppelin II and Houses of the Holy) When you look at the history of American pop music, you note carefully where the Brits come in, first with the Beatles and all of the subsequent bands that followed them. Then the next wave is about three to four years later, which would be Jimi coming over in 1967 and showing the Americans what they've been missing. And then following that in early '68, Traffic came over to the U.S. and a whole bunch of bands came over—and that went over into 1969 and 1970, and from that point on, the floodgates were open. There must have been twenty, thirty English bands that all did very well in the U.S.

HARVEY GOLDSMITH (U.K. promoter) The two people that introduced me to America were Ahmet Ertegun and Frank Barsalona. All the English acts that Frank signed, I promoted. So we were very, very close. I watched how he built the whole American territorial system up.

TERRY MANNING (engineer on Memphis sessions for Led Zeppelin III; founder of Compass Point studios) I was in a regional band in Memphis called Lawson and Four More, and we were the support band on a Dick Clark Caravan of Stars tour. They had several international acts on these tours, and I was very excited because the Yardbirds were one of them.

I made sure to introduce myself to Jimmy, and we just became friends. He was erudite, thoroughly together, very gentle and very unassuming—and obviously a musical genius. I just loved the guy immediately. He even told me about a couple of records that he had played on that weren't common knowledge then—and some that still aren't, where he was the secret guitarist.

The next tour was just the Yardbirds, and we weren't playing on it. I went to a few shows that were nearby. Jeff had just left the band, so there was some consternation about whether Jimmy could pull off the full lead/rhythm thing.

HENRY SMITH When Jeff left the Yardbirds, there was a different focus on what was going on: they knew from the very beginning that it was the last Yardbirds tour, but it was also introducing Jimmy to the world as a single musician. It was a coming-out party for Jimmy Page, the session guy that a lot of people didn't know in the States.

At the same time, the Yardbirds became two camps. McCarty and Relf and Dreja were one camp, and Jimmy and Richard Cole and Peter Grant were another camp. I remember sitting on the tour bus, and Keith Relf and Jim McCarty came up to me and said, “We're starting a new band after the Yardbirds are over, and would you like to come with us?” And then Pagey came to me and said, “I'm starting a new band after this, and I'd like you to work with me.”

By that time, Jimmy knew that he had a bass player, John Paul Jones. I think he had talked to Mo, John Paul's wife, to get that solidified even before he talked to Jonesy. I think she said, “Yes, he'll do it,” even before he did.

CHRIS DREJA (bassist with the Yardbirds) That last American tour was bloody great, because we knew we were going to finish. Ricardo Cole was always up to pranks. The trouble was that you had to be very careful with him because if you suggested something, he would go and do it. Anything—prankster stuff. He was a fixer. Especially in America, when a lot of the music business was run by the mafia.

I saw Peter with a gun in his belly on a bus after we played a State Fair in Canada. The promoter says, “I ain't paying you.” Peter gets up at the back of the bus, pushes his stomach out, and bumps the guy all the way to the steps, where they all fall about laughing. He says, “You're going to kill me for a thousand bucks?” I was on the bus. I saw it.

JIMMY PAGE After the San Francisco bit and it was down to four of us, the Yardbirds were doing really well in a live situation, but recording-wise we were working with Mickie Most, and he was really interested in singles, and we were interested in albums, and I know Keith and Jimmy McCarty lost the enthusiasm. They just didn't even want to be in a band called the Yardbirds anymore.

JEFF BECK [Mickie] didn't understand what the hell was going on with progressive rock, because he'd never meddled with it—it was all chunk-chunk stuff, Lulu and Donovan, easy stuff, where he could walk into the session and take over and say, “That's too loud, I want more acoustic guitar, Donovan louder and you softer.”

CHRIS DREJA The Yardbirds missed that wonderful moment when albums became king, and you weren't only as good as your last single. The only credible thing that came out of those sessions with Mickie was the one that Jimmy pretty much produced, because Mickie was not interested in albums, and he left us alone to do Little Games.

MICKIE MOST The Yardbirds were on the point of breaking up and becoming the first version of Led Zeppelin, but before they could do that, they had a commitment to finish another album, so I went into the studio with them, and we just made it willy-nilly. It was one of those things where I probably spent more time making bean soup than I did making the album, because nobody was really interested.

CHRIS DREJA Mickie never got it, but he didn't need to get it, because he was so successful with singles. He had a great eye for what was catchy, because a pop single never goes away. What he didn't have an eye for were bands like Crosby, Stills and Nash and Led Zeppelin. He didn't relate to musicians. He could only relate to session guys and that way of packaging it.

MICKIE MOST Jimmy really had his thoughts on his own thing. I'd already done the Truth album with Jeff Beck and Rod Stewart, and that turned out to be a very, very successful album in America … a seriously underground kind of album breaking out. Jimmy saw the marketplace, and Peter Grant, Jimmy, and I all contributed to putting together Led Zeppelin.

JIMMY PAGE In the Yardbirds I remember playing the Fillmore, and there was one song that we had called “Glimpses,” and I had tapes going of the Staten Island ferry and all manner of things, which was quite avant-garde at the time. As far as the power of it went, it never had the power of the rhythm section, but as far as the subtleties and the ideas, we had those areas within the Yardbirds. The Yardbirds [were] quite powerful within [their] own right, no doubt about it.

CHRIS DREJA There was all that funny business about Jimmy pulling the live album we did at the Anderson Theatre in New York. It was badly wired up, and they did a dreadful job with the audience sound, but a lot of people say to this day that it was the most exciting concert they ever went to.

JIMMY PAGE Epic said to us, “Can we do a live LP?” And they sent down the head of their light music department to do it. It was just awful, so they had to shelve it. They must have dragged it out of the vaults a few years later when they realized they had some unreleased Jimmy Page stuff, and out it came.

NICK KENT Jimmy always says, “I'm a musician, don't talk to me about anything else.” But he also had an extremely canny and very instinctual sense of rock image—of how to present himself and how to look. He was always checking out the way people like Keith Richards were dressing.

CHRIS DREJA He had great dress sense. When we toured America, he got us into trouble for wearing the Iron Cross and the Civil War cap and things like that. He was very provocative: although it may have been flower power, America was still run by the establishment. When we were in America, we got spat on by businessmen and basically treated like we were dirt on the floor.

MARTIN STONE (guitarist with the Action and Mighty Baby) I was walking down the King's Road, and I bumped into Jimmy with a mate. He was wearing the military jacket that all true South London blues guitarists wore at the time. But his friend was wearing a kaftan, and they both had beads round their necks. Jimmy said he'd just got back from San Francisco with the Yardbirds. He said, “There's a thing happening over there. It's called psychedelia.”