7

Whatever Jimmy Wants

I've always said Led Zeppelin was the space in between us all.

—John Paul Jones, December 1997

MARILYN COLE (wife of Richard Cole) Peter Grant had the utmost respect for Jimmy. Jimmy was his real special boy, the chosen one. Jimmy was God.

ABE HOCH (president of Swan Song in the U.K., 1975–1977) I think Peter had a love affair with Jimmy all his life. Jimmy was almost like an adopted child for him, and I think that Jimmy out of all of them was the most Machiavellian. The way Jimmy went was the way everything else went.

HELEN GRANT (daughter of Zeppelin manager Peter Grant) I can't ever recall Dad saying a bad word about Jimmy, really. He was absolutely devoted to him. I think it was, “Whatever Jimmy wants.”

MICHAEL DES BARRES (singer with Swan Song band Detective) Peter loved Jimmy with all his heart and would never accept anything Jimmy didn't want. Out of that came the idea that Led Zeppelin should be unapproachable. But it was an organic thing, it wasn't a strategy.

PETER GRANT What I can remember distinctly is driving Jimmy around Shaftesbury Avenue near the Saville Theatre after the split. We were in a traffic jam, and I said, “What are you going to do? Do you want to go back to sessions or what?” And he said, “Well, I've got some ideas.” I said, “What about a producer?” He said, “I'd like to do that, too.”

RICHARD COLE (Zeppelin's road manager) Jimmy was going to take the Yardbirds' name, and he was talking about getting people of the caliber of Steve Marriott or John Entwistle on bass and Keith Moon on drums. The idea was that it was going to be heavier than the Yardbirds had been. It's possible that he looked at the Jeff Beck Group as a template, but you could also say he was looking at the Who or Hendrix. What they all had was a great guitarist, a great bass player, and a great drummer. They had power. And then you had to find a singer to fit in there. When the Yardbirds were coming to an end, the guy he was thinking of was Danny Hutton.

JIMMY PAGE I was trying to build a band. I knew which way it was going to go. I'd been out to the States with the Yardbirds, and I knew exactly the way things were in place. I had a good idea of what style of vocalist I was looking for, too. The personality aspect—of course, that does come into it, but initially, if you've got a bond musically and everyone has that mutual respect for each other, well, that's going to give it the momentum.

AUBREY “PO” POWELL (designer of Zeppelin album covers, 1973–1980) It was Jimmy and Peter who started Led Zeppelin. Right at the beginning, there was a serious bonding of right time, right place, and right individuals. Peter had the clout, and Jimmy had the talent and the foresight to create Zeppelin. Jimmy and Peter were very close, and I don't think anybody to this day—not even Robert—knows exactly what that relationship was about, financially or otherwise.

CHRIS DREJA (bassist with the Yardbirds) I think Peter saw there was room for a band that wasn't pop but that delivered a great show that was really heavy. The Yardbirds were never going to be as heavy as Zeppelin, even as a four-piece, and there really weren't that many bands that encompassed the blues, the riff-making, the heaviness with a white singer. Jim was going to do the songs and the recordings, and Peter was going to take care of the business. And boy, did he take care of it.

RICHARD COLE Jimmy already had it in his mind that he was going to own the publishing. Whatever facet there was, he wanted to own it or part-own it. He'd written songs, so he knew a bit about the publishing side of it. He knew where all the money was.

CHRIS DREJA Jimmy really wanted to prove to people that he was going to end up with more money than them. That was one of his big motivations. I could see that very early on in his personality: “You may look down on me now, but one day I'll show you.” And he did. Eric wanted to be the penultimate bluesman, but Jimmy just wanted to be incredibly successful so he could tell everybody to fuck off.

RICHARD COLE Peter had two top guitarists, Beck and Page, but Jimmy was far more driven than Jeff. Jeff was a brilliant guitarist, but in those days he was a little unreliable. You could get him to the water, but you couldn't make him drink. If he decided he wasn't going to do a show, then he wasn't going to do it. And there were a few too many of those for my liking.

ROD STEWART (singer with the Jeff Beck Group) Beck needed a singer, and I was his singer; that was it. Everything was geared to his own playing. He used all of us. That's why he's had so much trouble keeping a group together.

NICK KENT (writer for New Musical Express) Rod had these horror stories about Peter Grant. He told me he'd started mentioning that he wanted the band to be billed as “The Jeff Beck Group with Rod Stewart,” and Grant got wind of this and said to him, “Listen, you're just a worthless little poof. Mickie warned me about you. He didn't want you in the group in the first place. It's only Jeff that wants you in the group, you and that other talentless cunt Ronnie Wood.”

BILL BONHAM (organist in Robert Plant's pre-Zeppelin band Obs-Tweedle) Peter told me that with the Beck Group, people were just raving about Rod. And they're getting ready to do this tour in America, and Peter gets a phone call from Jeff. Peter says, “Where are you?” And Jeff says, “I'm in London, and I've quit the band.”

MARK LONDON (comanager with Peter Grant of Stone the Crows and Maggie Bell) When Peter started with Zeppelin, Jeff Beck was making $7,500 a night in America. If he hadn't left Peter, I think he would have done a lot better.

ALAN CALLAN (president of Swan Song in the U.K., 1977–1979) Jeff could always get to what he heard in his head, but he had absolutely no vision of how he was affecting the culture. He was a pure guitar player, whereas Jimmy learned to express himself with a depth and clarity and purpose that just overtook everybody else. He had a completely different mind-set [than] Jeff: as a session player, he completely understood that he had three hours to go in and figure out a number; deliver something solid, focused, and commercial; and get out. There was no drama in that. And he brought that attitude to his writing and his stage playing.

RICHARD COLE Why Jeff didn't want to be a leader was because he didn't want to be responsible for anyone else. Jimmy was completely different. Peter knew that, with Jimmy, “This is what we're gonna do, and we'll get on and we'll do it.” It was more self-contained. Between Peter and Jimmy, they didn't have to rely on anyone else.

TERRY REID (singer with Peter Jay and the Jaywalkers, signed to a solo deal by Mickie Most) Jimmy was only in the Yardbirds for five minutes, but he wasn't going to allow a repeat of the album with Mickie. Nobody was going to produce the new group but Jimmy. He saw a big hole in the scene. Cream was gone. The Jeff Beck Group was never going to last. Jimmy knew the sort of band to fill that gap.

ROBERT PLANT I'd met up with Terry a year after the Listen single. There was a kind of package that went round England with Aynsley Dunbar's Retaliation, and there was Terry Reid and the Band of Joy. The three bands seemed to end up everywhere together.

TERRY REID Jimmy wanted to put this group together, and he said he wanted me to be the singer. I said, “What's the band?” But there was no band. Jimmy was just formulating what he might be doing. He asked Steve Winwood, he asked Steve Marriott; he wanted a certain type of singer.

NICK KENT There were a number of great white male singers—Paul Rodgers, Steve Marriott—but Terry, to my mind, was the best. I'm not sure it would have worked with Page, though. He wouldn't have been into something like “Dazed and Confused.”

TERRY REID I was very flattered, and I said, “Let's have a go when I come back off the Stones' tour.” But Jimmy said, “No, I want to put something together now.” I remembered seeing Robert and John in the Band of Joy, so I went tearing into the office to see Peter Grant, and I said, “You've got to hear these two guys”—not just Robert but the two of them.

ROBERT PLANT Terry said, “You've got to meet this guy who lives in Pangbourne and who's a great guitarist.”

BILL BONHAM Robert invited Jimmy and Peter to come up and see Obs-Tweedle play in Walsall. I was really happy for him because he was a friend. I said, “Jump on it!” I mean, I would have taken it. But the Yardbirds at that time were considered has-beens, so he wasn't sure if it was the right move. He felt really bad about quitting Obs-Tweedle, and it was partly for that reason that he helped me get a job with Terry Reid.

JIMMY PAGE Obs-Tweedle … were playing at a teachers' training college outside of Birmingham—to an audience of about twelve people … you know, a typical student setup where drinking is the prime consideration, and the group is only of secondary importance. Robert was fantastic, and having heard him that night and having listened to a demo he had given me, I realized that without a doubt his voice had an exceptional and very distinctive quality.

ROBERT PLANT There was a time where—in another day at another juncture in my life and everybody else's in this game—if you were a man and you couldn't sing a D above top C, you couldn't cut it. That whole idea of being a high-powered, high-octave singer was incredibly important, and often the whole critical analysis of your ability was based on just that. I was marooned in that place and still am to a large degree.

CHRIS DREJA I remember coming back in the car from Walsall and the discussion we had about Robert—because he was a hell of a shrieker and a little uncouth, and I'd been used to working with a singer who was not a shrieker but a songsmith.

ROBERT PLANT (speaking in 1969) I knew [the Yardbirds] had done a lot of work in America—which to me meant audiences who did want to know what I'd got to offer—so naturally I was very interested. I went down to Pangbourne. It was [a] real desperation scene, man, like I had nowhere else to go.

JIMMY PAGE He came down to my house. I think he was tarmac'ing roads at the time, and he came in and I had this quite sassy American girlfriend, and he must have thought, “This is alright.” I started going through material with him. I tried to size him up, because he'd had a solo career and two or three records. I thought, “Let's see what he's about.”

ROBERT PLANT I got so enthusiastic after staying down there for a week, I hitched back from Oxford and chased after John, got him on the side, and said, “Mate, you've got to join the Yardbirds.” I had nothing to convince him with, except a name that had got lost in American pop history.

BILL BONHAM I went with Robert over to John's flat in Eve Hill. Pat was not happy to see Robert, because John had a good job with Tim Rose. Every time John went with Robert, the money stopped coming in. So John took some persuading to join this new group.

MAC POOLE (Midlands drummer and friend of Bonham's) We were in the Black Horse in Kidderminster, and I saw Rob with Maureen. He told me about the New Yardbirds. He said, “We just need a drummer.” I said, “What about Bonham?” He said John was sticking with Tim Rose. John had serious bills to pay; he was living in the caravan with the old man breathing down his neck. Why leave Tim and join Planty after doing all those gigs with the Band of Joy when no one was interested in the band?

JOHN BONHAM I had to consider so much. It wasn't a question of who had the best prospects, but which was going to be the right kind of stuff.

MAC POOLE The only way to convince John was to take Grant and Page to see him and to talk him round. And, of course, they offered him more money. So he went back to Pat, and she said okay. I think Robert really wanted another Black Country boy in the band. He didn't want to be the only Midlands guy in a London band.

JOHN BONHAM Chris Farlowe was fairly established, and I knew [Joe] Cocker was going to make it, but I already knew from playing in the Band of Joy with Robert what he liked, and I knew what Jimmy was into, and I decided I liked their sort of music better, and it paid off.

MAC POOLE I saw the pair of them only a few weeks later in the Rum Runner, and I said to John, “Don't tell me, you're in the band.” And he said yes. I said, “Oh, here we go again.” That's when he told me they'd got an advance. And it was a lot of fucking money, three grand each! And from there, it was really a move into a different dimension, because nobody had ever got that sort of money. All of a sudden, John's got the Jag and the latest stereo system. For Pat, it was like winning the pools, though she was very philosophical about it. She thought it wouldn't last long.

• • •

JOHN PAUL JONES The first rehearsal was pure magic. I suddenly realized there was no dead weight in this band, and it was an exciting thing to find out. It wasn't like, “The drummer's dad owns the van, so we'll just have to put up with him.” I'd worked with a lot of really good drummers, but I was younger than all of them—except for possibly Clem Cattini, and he wasn't actually on the session scene when I first started. There were only two young guys on the scene at that time, and that was me and Jim. And I'm younger than Jim. So to find a drummer of my age group, at that professional level, and to find him that good, was revelatory. I knew immediately, “This is what I want to do.”

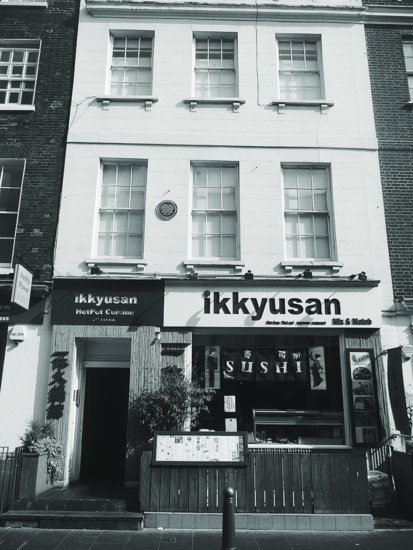

39 Gerrard Street, Soho: possible site of the first New Yardbirds rehearsal. (Art Sperl)

JOHN BONHAM I was pretty shy. I thought the best thing was not to say much but suss it all out. We had a play, and it went quite well.

JOHN PAUL JONES I'd worked with Jimmy, but never in that sort of situation. We'd always been scattered at the back of Manuel and His Music of the Mountains or something. In fact, I'd never been in a band like that, at that professional level. With Jet [Harris] and Tony [Meehan], it was a good band and it was great for me, but I never felt it was my music. Whereas with Zeppelin, obviously, the music came from all four of us.

ROBERT PLANT I didn't even know what we had. I was nineteen when I heard the tapes of our first rehearsal. I mean, it really wasn't a pretty thing. It wasn't supposed to be a pretty thing. It was just an unleashing of energy. But it felt like it was something I'd always wanted.

CHRIS DREJA The heaviness was creeping in. I wasn't John Paul Jones, and Jimmy McCarty was not John Bonham. These were the pivotal players who created that sound. I knew about John Paul, and I thought, “You're not going to top that, Jimmy. You're a lucky man there!” At that point, he was a better bass player than Jimmy was a guitar player—and, of course, he understood music. There was no way I was going to interface myself between him joining the band. And you couldn't have met a nicer guy. What a real ace gentleman he was.

HENRY SMITH (roadie for the Yardbirds and Led Zeppelin) Jonesy, out of all the musicians in Led Zeppelin, is probably the one that's most overlooked. He gave Page the ability to do what he wanted to do, without having to worry about the rest of the song. There was a set path: we know where we're starting, and we know where we're going to end up, but in between they could go any place they wanted to go.

GLYN JOHNS (engineer on the first Zeppelin album) John Paul was as responsible for the success of Led Zeppelin as the other three, though it's only the other three that people ever talk about. Why? Because nobody ever talks about the bass player. Though, of course, he was also a great keyboard player.

ALAN CALLAN At the beginning, they were going to use Keith Emerson as a keyboard player. And Jonesy said, “No, I'll play keyboards.” So the others said, “In that case, you have to play every other instrument, too.” I think he even learned the violin.

MAGGIE BELL (singer with Stone the Crows, later signed to Swan Song as a solo artist) Jimmy wanted this to work, and Peter loved his conviction that it was going to work. Jimmy could quite easily have gone for the rest of his life and made great records with people and been a session guy. Peter said to me, “This is quite frightening, Mags, but I think it's going to work because Jimmy's made sure it's going to work.” I was in the office when Peter said to him, “Jimmy, you're the one. You play the instrument. You've got the music in your head. I can keep all the shit away from you, and I can steer the band in the right direction.”

HENRY SMITH It was Jimmy's band. He put it together like you would put together a boy band. He was the leader of the pack. When he said, “Everybody go left,” everybody went left.

PAMELA DES BARRES (L.A. groupie and girlfriend of Page's in 1969–1970) It was really subtle leadership. I saw Jimmy's puppeteering control in an almost disguised way, but it was there. He pulled all those invisible fairylike strings. And I know Robert felt sort of under his … I don't know if control is the right word, because it was very subtle.

Good-natured Page: Melody Maker, October 12, 1968.

PHIL CARSON (head of Atlantic U.K. and confidant of Zeppelin's) Robert was a walking compendium of music. He knew more about blues music and the roots of rock 'n' roll than John Paul did—and certainly as much as Jimmy did—so he could absolutely hold his own intellectually when it came to working on the music.

JOHN PAUL JONES My father, who was a jazz musician, had turned me on to things like Big Bill Broonzy and Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, but beyond them, I didn't really know much about blues. I didn't know a lot about Delta blues; it was more urban blues, Muddy Waters. It was through joining Zeppelin that I found out more about the older guys.

BP FALLON (U.K. press officer for Zeppelin, 1972–1976) Everyone wants to have this picture that it was Jimmy, with the others sort of several steps behind and maybe Peter Grant in front of the rest of the band. Led Zeppelin was a band, and every band has a leader. Some have two leaders. To be a successful leader, you don't blow your leadership trumpet all the time. And that allows something to be cooperative, even when it would appear not to be. Does that mean everyone has parity? No. Does it mean everyone is a star? Yes.

GLYN JOHNS Jimmy never had a superior attitude with the others at all. They would have listened to him anyway, so he didn't need an attitude.

HENRY SMITH He was very centered, very quiet. He knew himself. And I think that had a lot to do with the chemistry of the band, because those were the types of people that he sought out when he went to start his band. Jeff Beck was like the high school bully, and Jimmy wasn't that way.

BRAD TOLINKSI (U.S. music journalist and friend of Page's) As much as everyone wants to depict him as controlling or Machiavellian, I've never heard Jimmy say a bad thing musically about any of the other guys … and I've talked to him a lot. He always talks about the chemistry and the alchemy in the most glowing terms. He may say he groomed and shaped them, but he won't say he could have done it without them.

JIMMY PAGE We still had some Yardbirds concerts to fulfill in Scandinavia, so we did some Yardbirds material, as well as some new numbers. We knew we just had something that other people didn't have. All four of us in the room knew this was beyond anything that anybody else was doing. Everyone was a musical equal, which was superb. We just knew that we had it there.

PETER GRANT I remember everything about that first show in Copenhagen. I remember everything Jimmy had told me about Bonzo, and the whole performance. It was so … exciting! Just to be part of it was fantastic. There was never a thought of, “God, this is going to sell X amount of records.” I thought they could be the best band ever. Remember that I'd been to America a lot of times, with the Animals, the Yardbirds, and different other bands. I just knew that Jimmy would come through. I knew it would be the best.

RICHARD COLE Jimmy once said to me, “The difference between Peter and most managers was he genuinely loved his bands. He loved Maggie, he loved Terry Reid, he loved Rod and Jeff, and he loved us.” It wasn't just a moneymaking machine for Peter, and they must have felt that.

ROBERT PLANT In Scandinavia, we were pretty green; it was very early days, and we were tiptoeing with each other. We didn't have half the recklessness that became, for me, the whole joy of Led Zeppelin.

JOHN PAUL JONES There was the North-South divide and a lot of friendly teasing going on. I think Robert was slightly in awe of us. To him, session men were pipe-smoking, Angling Times–reading, shadowy figures. He never knew what to make of me and to an extent still doesn't.

ROBERT PLANT Page and Jones obviously became friends [with me], but they were never mates like Bonzo was, because he and I started out with that age and experience gap that was never totally bridged.

JOHN PAUL JONES All four of us were middle-class lads; there wasn't that much difference between the way we were all brought up.

JIMMY PAGE I wanted artistic control in a vise grip, because I knew exactly what I wanted to do with these fellows. In fact, I financed and completely recorded the first album before going to Atlantic. We recorded the whole first album in a matter of thirty hours. That's the truth. I know because I paid the bill.

GLYN JOHNS Jimmy rang me up and asked me to engineer. I asked if there was a producer, and he said no. So I said, “Well, if I'm the only one in the control room, I'm going to end up producing it.” So he said, “Okay, you have to go and see Peter.” This all happened very quickly, within a matter of days. I went to see Peter in Oxford Street and said I needed to get an agreement, and he said no problem. We agreed on a percentage of the retail price, which was normal. And we shook hands. I wouldn't normally have gone into the studio without a contract, but because I'd known Jimmy and John Paul since we were virtually kids, it never entered my mind that there would be anything amiss.

ROBERT PLANT Led Zeppelin was created in a very crisp businesslike fashion. Nobody really knew each other. The record and the jamming that developed was what it was, and it was a very swift session. There were songs that began and ended cut-and-dried, like “Communication Breakdown” and “Good Times, Bad Times.” But the real thing about the group was the extension of instrumental parts, which was in full swing even before we made our first record.

GLYN JOHNS Led Zeppelin for me was so different from anyone else that it was like a completely new chapter. When I heard them on that first day, I can't ever remember being quite so excited. Blew my fucking socks off. Cream was nothing like it, because of the sophistication of Zeppelin's arrangements. That was the key. There was very little free-form anything; it was all very carefully arranged, by some pretty shit-hot arrangers. They were very hard-working: the Stones would take nine months to make a record, and these guys took nine days—including mixing. Were they trying to save money in the studio? More than likely.

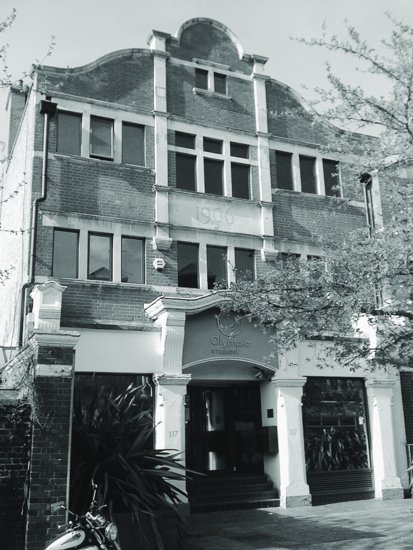

Olympic Studios, Barnes, southwest London, a year after the studios closed in 2009. (Art Sperl)

PHIL CARSON Zeppelin were more explosive than the Who or Cream or Hendrix. Taking absolutely nothing away from Cream, they were a little one-dimensional. Neither the Beck Group nor Cream had the ability to explode in the way Zeppelin did. Cream didn't have a Robert Plant on vocals, and the Jeff Beck Group didn't have a John Bonham or a John Paul Jones.

MAC POOLE Zeppelin was really an airplane. It was dead simple: Plant was at the front, Bonham was at the back, and the wings were Jimmy and John Paul. And it balanced out because those two knew each other, just like Robert and Bonzo knew each other. It was a London-Birmingham weld.

NICK KENT What gave Led Zeppelin its power was the mixture of Black Country muscle and the more kind of analytical southern ability to step back and see the big picture. There's an alchemy there.

GLYN JOHNS I didn't produce that band—in the sense that I had nothing to do with them until they walked into the studio. They were really well rehearsed, they'd picked all the material, and they knew exactly what they were doing. So half that job had already been done by them, and probably by Jimmy—who would certainly take the credit for it. However, once they were in the studio, I very much contributed to the production of that record, without any question at all—because that's what I thought I was doing and what I thought we'd agreed.

JAAN UHELSZKI (U.S. music journalist; traveled with the band on the 1975 and 1977 U.S. tours) Jimmy, to this day, thinks his greatest achievement was how he recorded Bonham's drums. It's like he made Bonzo who he was mythically, so it's really symbiotic.

BRAD TOLINSKI (editor-in-chief of Guitar World) Page's production of Bonham's drums is probably one of the biggest musical events of the past fifty or sixty years. It's had as much impact on popular music as Louis Armstrong or Miles Davis. The notion of putting the drums right up there with the guitar and the vocals is huge, as simple as it is. It's still being felt in hip-hop and in all contemporary music.

GLYN JOHNS Everyone always asks about the Bonham drum sound. And the fact of the matter is, they got the fucking sound. I'd recorded Jimmy and John Paul nine million times, but I hadn't recorded the other two. The sound from Bonham's kit was phenomenal because he knew how to tune it, and not many rock 'n' roll drummers know how to do that.

I only used to use three mics: the idea was to capture the sound the guy was giving you and not fuck with it. I did put Bonham on a riser, however, to try and get the maximum out of his kit. On those sessions I stumbled, by accident, across stereo drum mic'ing, and it made him sound even bigger. Your jaw was on the floor from the minute he counted off. It was like the meeting of the gods: Jimmy and John Paul found these guys who were as good as them at what they did.

MAC POOLE John told Jimmy, “Don't put me in one of those egg-box studios.” And, of course, Jimmy knew all the studios and knew which one would be best for drums. When I heard the album, I was surprised by how simple the drumming was. Bonzo told me, “I couldn't do anything, man.” I said, “Why not?” He said, “Coz Pagey wanted it really simple.” He told me Granty came up to him and said, “If you wanna stay in this band, do what you're fuckin' told … or leave by any window.”

LAURENCE MYERS Peter once famously said, after John Bonham got a bit lippy, “Could you play drums in a wheelchair?” It was a story that went around all the time.

MAC POOLE Bonzo said, “I wasn't taking him on, he was twenty-four fucking stone!” And I still say that that was the reason Zeppelin made it, because Bonham had somebody to control him. In Birmingham, nobody could do that.

GLYN JOHNS Bonham, being the phenomenal drummer he was, would not have been the easiest guy for any bass player to work with. But because John Paul had such a history of playing with every drummer under the sun, he knew how to listen—intricately and probably subliminally.

JOHN PAUL JONES I immediately recognized the musicality of it. John kept a really straight beat on slow numbers like “You Shook Me”—mainly because he could, and there aren't many that can. Lots of people can play fast, but to play slow and groove is one of the hardest things in the world. And we could both do it, and we both recognized it in each other. It was a joy to sit back on a beat like that and just ride it. It required intense concentration but intense relaxation at the same.

Within the same rhythm, we always had a choice as to how we would play it. That's what makes it musically interesting and musically exciting. And to the listener who doesn't know what you're doing, it sounds as if it's got texture and color and movement … and life!

GLENN HUGHES John was the most musical drummer I ever heard or had the opportunity to be friends with. He was a huge arranger for the band. People talk about Entwistle and Moon, but the subtle aspect of Zeppelin was the way John and Jonesy played together.

JOHN PAUL JONES You could dance to Led Zeppelin. Blues wasn't our only experience of black music. John and I were both into soul and funk, and I was into jazz as well. As a session musician, I did all the Motown covers because I was the only one who knew how to play in that style.

EDDIE KRAMER (engineer on Led Zeppelin II and Houses of the Holy) I think Jonesy led the parade there, in the sense that he'd really absorbed what the Detroit bass players were doing and what the Philly bass players were doing.

CHRIS DREJA On a good night Cream were great, but they were terribly raggedy at times. With Zeppelin, you had this sense of construction.

ALAN CALLAN John Paul—who to this day I think is probably the greatest musician I've ever met—orchestrated everything behind Jimmy.

MAC POOLE Musically, out of all four of them, I would put John Paul Jones as being the fucking man. He may play a very simple line on “Dazed and Confused,” but the guy's thinking for the mood is so musical, and that makes it work. Jimmy's a great guitarist, but without Jones in that band—without that fundamental—it would be nothing.

JOHN PAUL JONES In all honesty, I'd say that I probably should have paid much more attention to the writing credits in the earlier days of Zeppelin. In those days, I'd just say, “Well, I wrote that, but it's part of the arrangement,” or something like that, and I'd just let it go. Not realizing at the time that that part of the arrangement had more to do with the writing than just arranging something. I always thought that John Bonham's contribution was always much more than he ever received credit for. In fact, I know it was.

HENRY SMITH Most of the magic of the songs is between Jimmy and Jonesy. Jimmy would feel things out, come in with little riffs, and Jonesy would add his magic to it. Bonham could fill in any way you needed him to, and Robert adding vocals and words to it made it even more special. But the down-and-dirty part of it was Jimmy and Jonesy.

JOHN PAUL JONES Zeppelin was really a partnership between four people, and sometimes when you see songs with “Page-Plant” on everything, it makes it seem like it was a “Lennon-McCartney” situation, where they wrote everything and John and I just kind of learned the songs that Jimmy and Robert taught to us. That's so far from the truth it's ridiculous.