8

Atlantic Crossing

Ahmet used to say to me, “Only sign a band if there's at least one virtuoso musician in there. I don't care if it's the drummer or the keyboard player.” Led Zeppelin had four.

—Phil Carson, November 2010

JERRY WEXLER (president of Atlantic Records, 1953–1975) The main reason that Atlantic Records became a power in white rock 'n' roll—especially with English rock—is because we took the black thing as far as it could go. Atlantic made music for black adults, while Motown made music for white teenagers. Of course, we left Motown in the lurch, but how? With Zeppelin and Yes and Crosby, Stills, and Nash! We couldn't get black music to cross over. People have romantic delusions, remembering what never happened. Ray Charles and Aretha Franklin never really happened.

JERRY GREENBERG (general manager of Atlantic, 1969–1980) When I first came to Atlantic in 1967, I thought Jerry was the president of Atlantic and Ahmet Ertegun was the president of Atco. Because Jerry was signing all the Wilson Picketts and Ahmet was signing all the white rock acts.

AHMET ERTEGUN (cofounder of Atlantic Records) The British Invasion had tremendous repercussions. The Beatles and the Stones changed everything. Jerry considered the music derivative. Most of it surely was; some of it, however, was original.

JIMMY PAGE I had already worked with one of Atlantic's producers, and I visited their offices in America back in 1964, when I met Jerry Wexler and Leiber and Stoller.

AHMET ERTEGUN In the '60s, we had started to make records in England, as well as here, and one of our legendary producers, Bert Berns, was raving about these session players Jimmy Page and John Paul Jones. In those crazy days of London madness, Carnaby Street, the angry young men, the nightclubs, the Speakeasy, and the Revolution, I had run across and met both Jimmy and John Paul. When Peter Grant and Steve Weiss came to see us about a new group formed by Jimmy, we were very excited about the prospect of this new group, the New Yardbirds.

JERRY WEXLER Ahmet's gift for acquiring talent was remarkable. Whether in London or in L.A., his timing was impeccable; he was always in the right venue at the right time. His cool was irresistible to managers and artists alike.

DANNY GOLDBERG (U.S. press officer for Zeppelin and president of Swan Song in New York) Culturally, there's no question that Zeppelin benefited from the breakup of Cream. It created a vacuum. The quirk of the signing of Zeppelin was that Ahmet didn't sign them, Jerry did. Dusty Springfield had told Wexler about John Paul Jones, so it actually was a Wexler signing. But within a year or so, it became Ahmet's band, and Wexler stopped paying attention to them.

JERRY WEXLER I signed Led Zeppelin, and then I had nothing to do with them. Absolutely nothing. Ahmet took over their care and cleaning. I don't think I could have tolerated them. I got along fine with Peter Grant. But I knew he was an animal.

ROBERT PLANT Ahmet was a friend and [a] sidekick. He was yet another member of the Zeppelin entourage who came to us to fulfill his dreams of craziness or whatever. He was doing that as well with John Coltrane and Ray Charles, you know, which is even more amazing. He was a fucking incredible character and personality, with great wit and humor.

JUNE HARRIS BARSALONA (U.S. correspondent for New Musical Express and wife of Frank Barsalona) Ahmet was the one who could hang out on that very high, sophisticated level, so for anybody who wanted celebrity status, that was perfect: if you were seen with Ahmet, you were there. That was the ticket to the stars. If you were more interested in the music, you'd hang out with Jerry.

JERRY GREENBERG We didn't know Robert, we didn't know Bonzo. It was based on Jimmy and on Dusty saying how Jonesy was the most incredible musician. But why wouldn't you want to sign with Atlantic? It was the same with Mick Jagger. It was the heritage of Atlantic that caught the English people who were raised on that music, raised on blues, and made them say, “Man, I want to be a part of this.”

RICHARD COLE (Zeppelin road manager) I think Jimmy and Peter felt Atlantic was more bona fide than Atco, which was a subsidiary. Atlantic was the powerhouse.

AHMET ERTEGUN Signing Zeppelin was the result of our signing the Young Rascals. Steve Weiss represented the Rascals in the contract, and he was one of the toughest lawyers I had ever encountered. He made a terrific deal for them. Having done that, he liked us; we became very good friends. When Peter Grant came to America to make a deal for “The New Yardbirds,” Weiss was Grant's lawyer. So the man we complained about bitterly—because of the tough deal we'd had to make for the Rascals—became our friend. He became the man who brought us one of the greatest groups in the history of music.

JANINE SAFER (Swan Song press officer, 1975–1977) Zeppelin was certainly the first band to get the deal they got, and that was all Steve—maybe not all Steve's idea, but certainly all Steve's execution. Peter posturing and bullying would never have worked with Ahmet and Jerry. Steve being an incredibly good negotiator, it did work.

TERRY MANNING (engineer on Led Zeppelin III tracks) Chris Blackwell was right on the verge of signing Zeppelin to Island, and he had offered them autonomy and production, because that was his ethos. Peter then took that as leverage to Atlantic and got more money for the same deal: “Island is giving us all this, and you'll have to match that and give us more money, or we're going there.”

CHRIS BLACKWELL (founder of Island Records) It was a handshake deal, but I was dealing with Peter Grant, so it wasn't a deal until it was really a deal. And to tell you the truth, I'm glad I didn't get them because it wouldn't have worked for us at Island. Too dark. I couldn't have dealt with it.

JERRY WEXLER Clive Davis and Mo Ostin were also in the horse race, but I prevailed by offering Zeppelin a five-year contract with a $75,000 advance for the first year and four one-year options. Steve Weiss said that for another $35,000, we could have world rights. I called Polydor, our English distributors, and suggested they chip in $20,000, but they passed.

DICK ASHER (head of Epic Records in the late '60s) Grant and Steve Weiss arrived in Clive Davis's office, and we all sat down. It was Clive's first meeting with Peter, and we talked and talked about all sorts of things. Finally, Clive said, “Well, aren't we going to talk about Jimmy Page?” Grant replied, “Oh no, we've already signed them to Atlantic.” We were all stunned, especially after all we'd done for [the Yardbirds].

JERRY GREENBERG Steve told me, “You know how you got this band? It was because Clive Davis slammed the door in my face. And I never forgot it. I wanted to give it to him, and I gave it to him, boy. I snatched Jimmy up and brought him to Atlantic.” Steve was a sensitive guy, and people don't forget.

RICHARD COLE Steve got five percent of anything Peter made, but then there were no lawyers' fees. He used to drive us fucking mad because he was always writing memos and notes. I once heard Peter say, “Thank fuck I haven't got to pay him by the sheet of paper.”

BARRY JAY REISS (lawyer and colleague of Steve Weiss) Steve and Peter got along famously. Both of them were volatile personalities, so I think they felt at times like soul brothers. There were some screaming matches, but nothing out of the ordinary.

GLYN JOHNS (engineer on first Zeppelin album) Peter went to New York and got the deal with Atlantic, came back, and had a meeting with the band. I can only assume he told them what the money was and how it would be divvied up, and how the royalty situation would work out. And again, I can only assume that it came to me and my bit, and Jimmy said, “Oh no, he didn't produce it, and he's not going to get a royalty.” I think it was all right for me to have a royalty before the deal was done, but once there was a large amount of money involved, they changed their minds. I got a call from Peter, and I was told that I had no arrangement. I had been shafted royally.

JIMMY PAGE [Glyn] tried to hustle in on a producer's credit. I said, “No way, I put this band together, I brought them in and directed the whole recording process, I got my own guitar sound—I'll tell you, you haven't got a hope in hell.”

GLYN JOHNS Jimmy, since then, has been proved to have the most extraordinary attitude to anything he's involved with, which is that he will take credit for pretty much everything and never allow anyone else to have credit for anything. I never spoke to John Paul, who was a friend. I knew it was nothing to do with him. I don't even think it was Peter. I knew it was Jimmy, and it was Peter doing Jimmy's bidding.

CHRIS DREJA (bassist with the Yardbirds, photographer) I did the first photo session for Zeppelin in my studio before I moved to New York. I think the fee was 21 guineas. I have a theory that they commissioned me because they wanted to keep me sweet and not be funny about them using the Yardbirds' name. Years later, Jimmy, for some weird reason, informed me he had a piece of paper proving he owned the name. I think it was because at that point—along with his ambition to be the wealthiest man in rock and open up the Olympic Games—he liked the whole control thing.

• • •

EDDIE KRAMER (engineer on Led Zeppelin II and Houses of the Holy) I was finishing off some Hendrix stuff, and John Paul called and said, “I've got something I want to play you. Come over to the house.” So I went over, and he played me the first Zeppelin record. I said, “What the fuck is this? This is an incredible record!” He said, “It's the new band I'm working with.” So I said, “What's it called?” He said, “Led Zeppelin.” I said, “That's the stupidest fucking name I ever heard.”

JIM SIMPSON (mainstay of Midlands music scene) We didn't think the Yardbirds were that great: there were tougher and better in Birmingham. So when Bonnie told us about Led Zeppelin, we all got a fit of the giggles. “How could a band ever make it with a name like that? They've got no chance.” We all thought they'd gone off to join the London softies. We thought it was a really silly move. For about ten minutes.

TERRY MANNING The first album was revolutionary. It was fresh, it was powerful, and it still had pop sensibilities. It was really just an amazing recording, a shot out of the dark. There was a heft to it. They were recording in the same place as several of the other big bands, with some of the same technical and production staff, so the difference had to be the players. And those four just had a copacetic mingling of all their sensibilities and tones. It was overwhelming and undeniable.

ELIZABETH IaNNACI (artist relations in Atlantic's L.A. office, 1975–1977) There's a purity and a spareness about that first record that the later records don't have. I remember putting the stylus onto that vinyl and playing “Communication Breakdown.” And the world changed in that moment. It was like reading Gertrude Stein for the first time or seeing the first Cubist painting. The world was never to be the same again.

ROBERT PLANT I'd only written one song prior to meeting Jimmy, and that was “Memory Lane.” So from writing nothing to cowriting “Communication Breakdown” was quite a move.

GLENN HUGHES (singer and bassist with Trapeze, Deep Purple and Black Country Communion) “Good Times, Bad Times” was the first time I really heard Robert. I thought, “Oh shit, that's what it's about, is it? We've had Cream, and now we've got this.” I didn't even know what they looked like, but just listening to that song, I thought, “Ooh, I bet they look good and all.” You could see it and smell it.

MICK FARREN (singer with the Deviants and writer for underground press) The whole Cream thing had happened, and to us it was like, “Here comes another one.” In other words, somebody on high picks their dream band and puts it all together, but who the fuck's the singer—or the bass player and the drummer, for that matter? There was the same kind of vibe about it.

DAVE PEGG (bassist in Bonham's pre-Zeppelin band A Way of Life) Bonzo turned up one day in his mother's estate [station wagon] with a copy of the album just out of the blue and said, “You've got to hear this.” It was fantastic. The following week, he turned up in a gold S-type Jag. They obviously took off really quickly and became huge, because Robert bought a similar gold S-type Jag. The two of them had identical cars for a while.

ROBERT PLANT We had no idea of success. You couldn't really say to people, “We're doing really well.” Because it was like an existentialist thing—one minute we were doing gigs and people were going nuts, and the next minute I was back in the industrial Midlands of England, trying to justify having a Jaguar.

ROY WILLIAMS (live engineer for Robert Plant) Robert and Bonzo used to go to the Plough and Harrow in Kinver. They'd go in Bonzo's Jag, and on the way back—so they didn't get stopped by the police—Bonzo would put on a chauffeur's cap, and Robert would sit in the back.

DAVE PEGG John still lived in a council flat in Eve Hill, which was quite fascinating. The way the flat was done up was all nouveau riche. It was like being a pools winner, I suppose. A chap from the Midlands, and all of a sudden he's got all this dosh. In the couple of months from when he got the flat to when he left it, he'd transformed it, and it'd got an oak-paneled sitting room and gold chandeliers, and all the taps were gold. It was like he'd bought up Rackhams department store, which was the posh shop in Birmingham.

ED BICKNELL (former manager of Dire Straits) I was the social secretary at Hull University. I came to London in late 1968, and during that trip, I went to the Chrysalis booking agency at 155 Oxford Street. While I was in there, this huge figure entered the room, and I was briefly introduced to Peter, who was trying to get the agents at Chrysalis to go see the New Yardbirds at the Marquee. Being agents, they all studiously ignored him, but I toddled down to Wardour Street and found myself in a queue that stretched all the way round the corner into Old Compton Street.

PETER GRANT When I saw that queue in Wardour Street, that convinced me. I thought, “That's it—no singles, no television.” Because if the people believe in the band, they're going to come and see them.

ED BICKNELL I thought they were the absolute dog's bollocks. They didn't know a lot of songs, and the guitar solos went on a bit, but the energy of the band, and particularly the rhythm section, you were just thrown back by it. And I left thinking, “I've got to book this group,” which I duly did for £100, supporting Jethro Tull, who got £400. In between the time I booked the New Yardbirds and the time they were due to play, they became Led Zeppelin. In the contract, Peter crossed out “New Yardbirds” and put “Lead Zeppelin,” spelled L-E-A-D, and signed it “Jimmy Page.” They never played the show because they went off to the States instead.

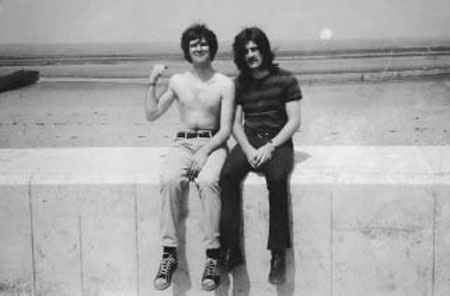

Dave Pegg and John Bonzo in Barmouth, Wales, summer 1968. (Courtesy of Dave Pegg)

ROY CARR (writer for New Musical Express) Most people had written the Yardbirds off, as they had Manfred Mann and people like that. Somebody told me the Yardbirds were changing their name, and Peter Grant was running around the Fishmonger's Arms and all those places. And that was it, they went to the States, and it happened much faster than anybody imagined.

CHRIS WELCH (writer for Melody Maker) I got this phone call from Jimmy, who'd been tipped off by Neil Christian that I was okay—a journalist he could trust. He just appeared in the Melody Maker office and told me about his new band. I said, “Well, what happened to the Yardbirds?” He said the band had got a bit slack toward the end. He used a very Home Counties expression—something like, “Come on, chaps, we're not putting enough effort into this!”

He never ever used Americanisms, Jimmy. It was all very English, whereas everyone else was trying desperately to adopt American rock slang, and he never did. He was his own man and stood apart—very self-assured in that respect, and checking people out in the way he checked me out. I wrote down the new name of the band, and he corrected my spelling: “It's L-E-D, not L-E-A-D.”

REG JONES (singer and guitarist with Bonham's pre-Zeppelin band A Way of Life) I drove John and Robert to their first engagement as Led Zeppelin in my Jaguar. It was at Surrey University. There was a huge banner hanging outside that read—in big letters—“Tonight! The Ex-Yardbirds.” Underneath, in small lettering, it said, “Led Zeppelin.” After the gig, I couldn't start the Jaguar and we all came home on the train.

JOHN PAUL JONES Originally, I think I probably went into the band thinking, “Give it a couple of years.” Was touring with Zeppelin more tiring than session work? Probably not, at the rate I was working as a studio musician. The music I was doing on the session scene was just … I was basically dying in any creative area. I was literally just working. And Zeppelin was total release.

ROBERT PLANT Did I know it was going to be special? It just seemed to be the way I'd always wanted it to be in the Band of Joy. Of course, with Jimmy and Jonesy there was a seniority. They were mature and more worldly wise, while Bonzo and I were a pair of chancers, really, nicking the hubcaps off the cars of people who'd invited us in for dinner. We learned a few graces, and it was great. It felt unbelievably powerful and unashamedly so.

KEITH ALTHAM (writer for NME, Record Mirror, and other publications) Peter phoned me at the NME and said, “Come and see my band, Keef. They're playing in Elephant 'n' Castle.” I got there about seven-thirty, and I could hear them about three blocks away. I'd never heard, in a confined space, a band playing so deafeningly loud. I stood it for about three numbers, and my ears started bleeding.

It sounds like heresy, but they weren't that good. They were obviously good musicians, but they weren't playing like a band. I decided it was one of those supergroups that just wasn't going to work, and I left. Peter phoned me the following day and asked what I thought. I told him. Of course, thereafter he never ceased to remind me of what I'd said: “Whatchoo fink of my band now, Keef?”

MICK FARREN A few months after the Band of Joy opened for the Deviants, it all turned around. Now we were opening for Led Zeppelin. There is some dispute about this—Russell [Hunter] swears it was Bristol; I think it was Exeter Civic Hall—but when we turn up, there's this big truck outside. And it was like, “Who's paying for this nonsense?”

We all came in, and the stage was full of their equipment. Then the lads show up, and Jimmy and Robert are perfectly friendly. Even then, John Paul seemed to be nine paces apart from everybody else. And then there was the loathsome Bonham: Keith Moon with all of the dynamite and none of the charm.

The gig was a violent mess, a culture clash with a bunch of ignorant fucking farmers. When we came offstage, we said to Zeppelin, “They almost killed us out there.” Robert said, “Wow, you must have been terrible.” I said, “Try it.” And it just got worse. They hated him even more than they'd hated me.

JEFF BECK I could see the potential. It was just amazing, blew the house down, blew everybody away…. I was blind jealous, although maybe jealousy is the wrong word, because it's a negative emotion.

ED BICKNELL Peter had a street wisdom. He understood what musicians were about, and he understood the audience, which a lot of people in the business don't. He understood that if you can get fifty people going mad in a tiny club, it's not a huge leap to getting half a million people going mad in a stadium. He always said to me that the most important thing was the word-of-mouth.

JIMMY PAGE When our first album came out, the way you had to promote it was on the television and the radio, and at the time you'd fit into somebody's show and do three or four numbers, and eventually there was a John Peel show. That was the one avenue you had. The other was television, and we weren't going to mime. We were playing live, but quite honestly we didn't fit into the format of TV at that time.

KEVYN GAMMOND (guitarist in Plant's pre-Zeppelin group the Band of Joy) The first time I saw Zep, they'd already got the whole showmanship sorted out. It was almost like the time I saw T-Bone Walker in Birmingham, with the guitar behind his back and doing splits. Jim had that same kind of persona, where he could make it work away from just a semi-pro thing, which I guess we were. But Robert and John also took the Band of Joy framework into Zeppelin.

ROBERT PLANT Jimmy brought his mastery and technique and an extension of the Yardbirds signature to the proceedings. But Bonzo and I were already in this freakout zone with the Band of Joy. It was quite natural for us to go into long solos and pauses and crescendos. I listen to it now, and it swings, it has all those '60s bits and pieces [that] could have come off the Nuggets album.

So for Jimmy it was an extension of what he did, and for us it was an extension of what we did. The only difference—and it was the crucial thing—was that there was such quality playing. John Paul had found a place so way down in that pocket that Bonzo just fell into it.