9

Like a Freight Train on Steroids

Nineteen years old and never been kissed, I remember it well. It's been a long time.

—Robert Plant, March 1975

PETER GRANT I sat down with them in October 1968 and said, “Listen, you start on Boxing Day for ten or twelve dates in America with Vanilla Fudge, which means you've got to go on Christmas Eve.” And I was shitting myself having to tell them, “Incidentally, fellas, I'm not going.” It was one of the few times I never went, and I regretted it so much that I thought, “I'm never going to not go with them again.”

RICHARD COLE (Zeppelin's road manager) The first tour was paid for by Jimmy and Peter and John Paul out of their own money. My first introduction to them as a band was when they flew into LAX with Kenny Pickett on the 23rd of December, and I went out to the airport to meet them. I already had Terry Reid and his band at the Château Marmont.

BILL HARRY (Zeppelin's first U.K. press officer) Richard Cole stuck to them like glue. He was the equivalent of a fifth Beatle, in a way, in that he was always there. He looked after everything. He was always doing things. If Bonzo ripped his trousers onstage, Richard fixed them.

CHRIS WELCH (writer for Melody Maker) Richard was a breed of real tough Londoner who could be incredibly charming at the same time. He would be very polite to girls and then turn around and swing a punch. Zeppelin was a strangely small entourage, like a little family. It always amazed people how few of them there were. At the start, anyway, it was just the band and Peter and Richard.

MICHAEL DES BARRES (singer with Swan Song band Detective) Cole was their rottweiler pimp. You did not want to fuck with him. He's the gentlest, sweetest man today, but back then, he would shove a coat hanger up your ass and hang you out the window. All of the Zeppelin road incidents were in essence choreographed by Ricardo.

No entry: Ricardo closes the door on Jimmy Page, 1969. (Chuck Boyd)

RICHARD COLE They were both very sweet, Bonham and Plant. I was twenty-two, only two years older than them. Jimmy and I had shared a room in the Yardbirds days, so I had a two-bedroom suite ready for him and me. Bonzo and Robert had a bungalow or a suite on that first tour, and then there were John Paul and Kenny Pickett.

ROBERT PLANT We ended up in the suite Burl Ives had just vacated. Down the corridor were the GTOs, Wild Man Fischer, and all those Sunset Strip characters of the time. Rodney Bingenheimer was making coffee … [and] all that dour Englishness swiftly disappeared into the powder-blue, post-Summer-of-Love California sunshine. I was teleported.

RICHARD COLE On Christmas Day, I went to see a girl up in Laurel Canyon, so the band had Christmas dinner together. I think Bonzo cooked the turkey.

CHRIS WELCH Robert was always gently taking the mickey out of Bonzo, and Bonzo would get irate about it. But you could tell they were very fond of each other.

RICHARD COLE The ones that used to row were Bonham and Plant. It was never about the music, it was usually about one of them not wanting to pay for the petrol when they were driving back to Birmingham—things that were so amusing to us because their arguments were like arguments between two brothers. Because they both came into the band at the same time as outsiders, I suppose, and I'm sure must have felt that in their own conversations.

ROBERT PLANT It was much easier for John to connect with me in my changes than it was for the other two guys. Because we were from the same place and because we'd played together before, he could tap into parts of me that Jimmy and Jonesy either didn't know about or didn't bother to connect with.

PAMELA DES BARRES (groupie and girlfriend of Page's in 1969–1970) Unlike a lot of bands, Led Zeppelin did actually hang out at clubs and restaurants together. They really did like one another.

JOHN PAUL JONES There was that whole sort of hippie hangover, where all the bands used to live together, yet by the time they got on the road they were at each other's throats. Whereas we were always really pleased to see each other at the airport on the first day of the tour, and I'm sure that had something to do with the longevity of the band.

There weren't any camps in Led Zeppelin. People think it was like Jimmy and Robert were always together, so that would leave the rhythm section. But then it was always the Midlanders and the Southerners—lots of good-natured banter. We'd take the piss out of them, and they'd take the piss out of us: “You poncey Southern so-and-sos…. ” But we were all very protective of Led Zeppelin. Any member attacked by the press, we would all rally round … and probably still do. There's still that defensiveness.

BILL HARRY Robert was absolutely loads of fun. He was the joker in the pack. When you were in his company, you felt completely relaxed and there were no tensions.

CHRIS WELCH Robert had an extraordinary boyish exuberance. I once saw him come into a hotel foyer and do a forward roll across the floor. In the hotel bars, all the girls gravitated toward him; he would never be sitting there alone. A lot of rock musicians would be very crudely on the pull, and Robert would never do that, he was just magnetically drawing girls toward him. He would never go for any groupie who happened to throw herself at him.

KIM FOWLEY (L.A. producer and scenester) Led Zeppelin fell in love with Los Angeles because there are certain places where everybody says yes, instead of being stuck in Grimsby or Belgium. The physical Englishmen liked L.A., while the cerebral ones liked New York. L.A. fell in love with Led Zeppelin because we're connected to England. When a new English band came over, we wanted to be the first people on our block to welcome them at the club. It was, “Let's go down and steal their essence and consume their magic.”

ROBERT PLANT We couldn't believe we were in the States. Everything was new to us. Meanwhile, Pagey was walking around like a king, the King of the Yardbirds, with all these chicks.

KIM FOWLEY Jimmy came up to my room at the Château Marmont and said, “Hey, take a look at my new bullwhip.” And he showed me this whip that Aleister Crowley would have drooled over—a spectacular item. He had the dark clothes on and the velvet cuffs. He was decked out, and this was three in the afternoon. He wasn't about to go onstage. The shy boy I'd met in 1965 was suddenly a very confident young man; he was the Jimmy Page who is the subject of folklore. Still polite, but with some edge on him that he hadn't exhibited before.

PAMELA DES BARRES When I first met Jimmy, he wasn't taking drugs at all. He was very in control of himself and liked to have the girls a little out of control. I never minded it. I enjoyed it and felt totally safe. I know a lot of people talked about his whips and the things he did, and maybe he did those things, but he was very respectful of me and never harmed me. Apart from breaking my heart, of course.

RICHARD COLE The first show, in Denver, was in the round, and you really couldn't get a good idea of a concert when it was in the round. They were supporting the Vanilla Fudge, who were friends of mine because I'd tour-managed them. Bonham and Jones had this mutual respect between them and Tim Bogert and Carmine Appice.

ROBERT PLANT Colorado was so beautiful and gentle compared to L.A., but I was petrified by the hugeness of the venue.

RICHARD COLE It was maybe during the fourth show, in Portland, that they started to gel. I remember watching Bonham's solo with John Paul Jones and saying to him, “Fucking hell, this guy's really something.” Jimmy was an old hand at America, but the others were relatively new to working there, and I think they had to feel the audiences out and get comfortable with them. They'd never played to thousands of people before, and I'm sure it was very intimidating.

JIMMY PAGE Led Zeppelin's live performance was so important as to the sum of the parts and how we would go on stage. If all four of us were really on top of it, it would take on this fifth dimension. That fifth dimension could go in any direction in any way. Sometimes you'd do one number, and it would be really quite slow and dirgey, and the next day it would be quite fast. We stuck to the set list quite a lot, but the reason was that we were changing the numbers so much within that; the improvisation and spontaneity were happening all the time, and that was the beauty of it.

GUY PRATT (bassist with Page's post-Zeppelin band Coverdale/Page) When I played with Jimmy in the late '80s, he would listen to all the Zeppelin bootlegs. He was always interested in how they played things at certain gigs. Because everything was different every night, so they would just hit on a new arrangement. Jimmy would say, “Oh yeah, that's when we started doing that.”

ROBERT PLANT I was just so pleased to be there. I didn't even know what to do with my arms. Now I understand why Joe Cocker did that thing for a while, because what are you going to do? There are so many solos. But it was such an amazing time, and things moved at such a rate of knots. On 80 percent of the nights, it was an absolute extravaganza for me to be around it.

If you look at all the sort of bits and pieces I used to throw in for my own enjoyment—I mean, it's a bit corny now, because it's referring to Eddie Cochran or Elvis—it was the previous generation of rock 'n' roll. It was what we feasted on to get riffs, to get organized, to become a big band with big riffs. So I was kind of visiting most of the time in Led Zep. On that aspect of the British rock-blues thing, on “How Many More Times” and “Dazed and Confused,” those extensions had me … interestingly foxed for a while.

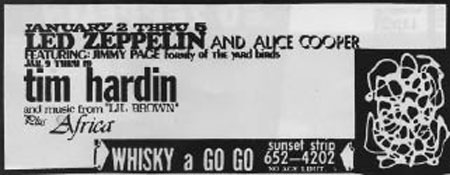

CATHERINE JAMES (L.A. groupie and girlfriend of Page's) The Led Zeppelin debut at the Whisky a Go Go wasn't that big of a deal—they were complete unknowns. But when they played, Wow! That was when things really changed. That was a turnaround for music in Los Angeles…. After the Zeppelin gig, you saw the beginnings of a whole different lifestyle. That's when the groupies started coming out of the woodwork. They started coming in from the Valley.

MIKAEL MAGLIERI (son of Whisky a Go Go founder Mario Maglieri) The Whisky was the place where groups hung to see other groups. That really was the basis of the Whisky: whoever was in town, even if they weren't playing, they all hung out together.

Zeppelin make their L.A. debut at the Whisky, January 1969.

RODNEY BINGENHEIMER (L.A. scenester and DJ) I remember being backstage, and Jimmy had the flu. He was green. He was very ill, and they went and did the show. They were just really cool, but Jimmy was real sick, so he wasn't very talkative.

PAMELA DES BARRES Richard Cole carried Jimmy off the stage. It was so dramatic. He had on red patent leather slippers, and they dropped off his feet as he was being carried out. Afterward, I said to myself, “Okay, that was pretty amazing, but I'm not sure I want to get to know those people.”

JIMMY PAGE We went to California and caused a bit of a fuss there, especially at the Fillmore in San Francisco, and all of a sudden, the name of the band traveled like wildfire.

ROBERT PLANT Bonzo and I looked at each other during the set and thought, “Christ, we've got something.” That was the first time we realized Led Zeppelin might mean something; there was so much intimacy with the audience, and if you could crack San Francisco at the height of the Airplane, Grateful Dead period, then it meant something.

JIMMY PAGE There were bands and we were supporting them, but they weren't turning up, and that was happening on the West Coast and the East Coast. So we were really quite an intimidating force.

JOE “JAMMER” WRIGHT (Chicago blues guitarist and Zeppelin roadie) Zeppelin was like a freight train on steroids, a huge machine coming at you. And it had a lot of funk to it. I went, “Holy fuck!”

JAAN UHELSZKI (writer for Creem magazine) I used to work at the Grande Ballroom in Detroit, and since I worked there, I saw all the bands free. I saw from the schedule that Led Zeppelin was coming through, and I knew that Page was in it. I already had this Page obsession from the Yardbirds, whom I'd seen the year before.

That first gig, they weren't as foppish and beautiful and refined as they became with all the brocade and outfits. I think they were just wearing jeans and T-shirts and leather jackets, very meat-and-potatoes dressing. Pam Grant reviewed that first Detroit show for Creem, and I think she called them “capable” or something ridiculous. The first show was maybe only half-full, but everybody who was there told everybody they knew, and by the third show it was full. That's how good they were.

I'd seen Cream that summer, and they were really prosaic compared to Zeppelin. Clapton had that imperious, lording-it-over-the-crowd thing, but there was something much more intricate and musical and exciting about Zeppelin. And it was very sexualized from the first album onward: they really were trying to get in your pants and didn't make any bones about it.

BEBE BUELL (celebrated rock consort and girlfriend of Page's) One of the reasons people feel there is something satanic about the lure of their music is because it was very primal—what it did to your head and the way it captured you. With the Stones, I thought about sex; with Zeppelin, you felt … danger.

MARIO MEDIOUS (Atlantic Records promo man, 1965–1972) When I heard them singing about the killing floor and squeezing the lemon till the juice ran down your legs, it freaked me out because I was raised up on that music. But it was more exciting the way they did it. I had grown up with Muddy Waters and Buddy Guy, but I had grown bored with it. It didn't mean shit to me anymore. When these cats came along with their electric shit and putting all that energy into it and taking solos an hour long, it knocked me out. It made me appreciate my heritage even more so.

JOHN PAUL JONES We played four nights at the Boston Tea Party, and by then we had an hour and a half's music to play. We played four and a half hours on the last night—we played the act twice, and then did everybody else's act with Who, Rolling Stones, and Beatles numbers.

MARIO MEDIOUS They got about ten encores at the Tea Party. People would not even let them leave, so they just kept playing. You could hear the whole building moving and shaking. It ended up with just blues jams and Jonesy moving back and forth between bass and keyboards.

PETER GRANT [Zeppelin] absolutely pulverized them … people in the audience used to tell me it was like a force. It was in their heads for three or four days. I thought, “There's no holding them back now.”

JOHN PAUL JONES Peter hugged us at the end of the gig, picked all four of us up at once. We knew we were actually going to make it.

AHMET ERTEGUN (cofounder of Atlantic Records) Peter defended the band as though they were his only children in life. He was a sensational manager: he built an aura of mystique around that group that still exists.

BILL HARRY Peter wanted me to do their publicity, but really it was non-publicity. It was to keep the press off their backs. They didn't want to do interviews, and he didn't want them to do interviews, so it was basically to filter them out.

JOHN PAUL JONES We allowed ourselves to be guided by Peter, and we trusted his decisions…. His idea was to be everywhere—and then nowhere. Just at the point where everyone was going to get fed up with seeing us, we were gone! He was just right, all the time. A lot of Americans helped us, like Frank Barsalona. The bright ones could see what [Peter] was doing and could understand what he was getting at…. He was a very smart man, which wrong-footed them. They just saw a big guy and thought if they could move quickly they could get round him.

DENNIS SHEEHAN (assistant to Robert Plant on the 1977 U.S. tour; subsequently tour manager for U2) Peter didn't get where he was by being a nice guy. Could he have managed U2? I don't think so. But could Paul McGuinness have managed Led Zeppelin? I certainly don't think so, either. Very different management techniques for their times.

PETER GRANT It's what I call verbal violence. You don't actually say, “I'm gonna do this to you,” but you intimidate them. That's the game, intimidating them verbally. And I realized that if you were British, you could really do it, because you could always out-verbal them any time you wanted to. They had a great thing of calling you “Pal,” and I'm like, “I'm not your pal. How dare you address me like that! I hardly know you, you wretched little man.” And they'd think, “Fucking hell, what's that all about?” [They'd] never heard anything like it before.

EDDIE KRAMER (engineer on Led Zeppelin II and Houses of the Holy) I remember Peter laughing at me and saying, “Not bad for an old gypsy, am I?” He was a tough boy. You didn't mess with him. If you're going into a record company or an agency or a venue, it's nice to know you've got Peter Grant there. He was like a walking mountain, but he was also very smart.

LAURENCE MYERS (partner with Mickie Most and Peter Grant in RAK Records) Peter realized what he had, which was that Zeppelin were really, really important. If you are unquestionably a huge star, you can push and push and push, and people will stand for it.

LISA ROBINSON (New York correspondent for Disc, New Musical Express, and Creem) Ahmet always knew where the power was, and so his focus was always slightly more on Peter and Jimmy than on Robert.

MALCOLM McLAREN (manager of the Sex Pistols) Jimmy was the artist Grant most admired—the only character he ever compromised with, because he believed artists had a gift from God. Theirs was a meeting of the physical and [the] cerebral. Grant played the ugly Igor to Page's irresistible Dracula.

SHELLEY KAYE (assistant to Steve Weiss) Peter was not the most handsome guy in the world, but he was actually quite dazzling as far as personality went. He was our protector. He was the one we were making sure everything was good for.

HENRY SMITH (roadie for the Yardbirds and Led Zeppelin) I've heard many people say he was a big bully and a mean type of person, but to me, he wasn't. He was almost like a father figure.

JUNE HARRIS BARSALONA Regardless of how other people perceived Peter, I always had a soft spot for him. He could be a baby. When you got on a plane with him, he was terrified of flying. He'd sit there and grab your hand and not let go until that plane landed. We spent a lot of time with him—down time, personal time, which was how we knew Gloria and the kids. Gloria came to New York at least once or twice. I remember her coming up to the apartment and having dinner. They were a regular husband and wife.

GLORIA GRANT (wife of Peter Grant) I didn't really know what Peter was doing, even though we were in the same house. It wasn't easy when he was away a lot of the time. And when he wasn't away, he was on the phone sorting things out. He was always on the phone with Steve Weiss. He found it very difficult to switch off. I think when we moved from Beulah Hill to Rose Walk in Purley, that was when I realized that he was making lots of money. The first time I met Zeppelin, we stayed in the penthouse suite at the Fontainebleau in Miami, and I said to Peter, “How much is this costing?” And he said, “Seventy-one pounds a night.” I said, “Seventy-one pounds?”

HOWARD MYLETT (author of the first book on Zeppelin) Peter and Richard together had really sussed out the whole American underground and also the youth and universities—what was selling and why albums were selling.

ED BICKNELL (former manager of Dire Straits) Because Peter had managed the Yardbirds and the Beck Group—and gone to America with them—he realized there was this underground scene in the States, and you didn't need pop radio play to access it. In fact, in some ways pop radio was a disadvantage because it had no street cred.

HARVEY KUBERNIK (L.A. correspondent for Melody Maker in the '70s) Our friends in Led Zeppelin walked into the glorious world of FM radio and free-form unrestricted format. These little things were even migrating through pop magazines or papers across the United States in a pre-Internet world where J.J. Jackson at WBCN in Boston knew the son of promoter Don Law.

ANNI IVIL (press officer for Atlantic in the U.K. office, late '60s–early '70s) They had Peter Grant, Frank Barsalona, Atlantic Records, and every major promoter working to make them succeed because it was in everybody's interest. All they had to do was deliver.

JUNE HARRIS BARSALONA There were so many groups being formed at that time. The difference with this one was that, from the get-go, it had all the elements to make it happen. If Peter got involved with something, it was going to succeed. And it was reflecting what was going on in the late '60s: 65 percent of the American population was under thirty-five, and there was a big revolution going on in San Francisco. England still had a prominent position in what was going on in the development of rock, so you were more likely to listen.

DON LAW (Boston rock promoter) English bands? Straight ahead. They were consistently better focused and prepared to play that market. There was an energy and intelligence that wasn't there from the West Coast bands.

EDDIE KRAMER Zeppelin had a deal with Concerts East and Concerts West, and we all know who those geezers were. They split up the country into two sections, and it was very clever the way they put it together. If that's what it takes to move ahead, go for it. But it all contributed to this feeling that they were invulnerable.

ELLEN SANDER (U.S. journalist who profiled Zeppelin for Life magazine in 1969) They were considered one of the most interesting of the new blues-based bands: one to watch, a powerhouse. By then, the British Invasion was a fait accompli, and British bands were not alien at all. There was already a sense of legacy, and Jimmy Page was a part of that. They came over to my place after a lunch, and we listened to Elvis records. They behaved perfectly. Their publicist, Diane Gardiner, told me they thought we got on very well.

JERRY GREENBERG (general manager of Atlantic, 1969–1980) Mario Medious—the Big M—was an accountant at Atlantic, but he would talk trash to me about these bands. So when I came up of the idea of somebody going on the road to start promoting to FM stations, I went to Mario.

MARIO MEDIOUS All these college and hippie stations started up. All of a sudden, they're playing esoteric music—blues, jazz, rock, pop, folk—but they're playing it from an album, not a two-and-a-half-minute single like on AM. I had a white-label test pressing of the first Zeppelin album, and I started promoting that to FM radio.

The first place I got the record played was New York City, on WNEW on Alison Steele's nighttime show. I took a test pressing in there and told her it was the new Yardbirds album. I had her play the whole album. I left New York and went to Boston and did the same thing at WBCN, and they went crazy over it. The distributor up there told me he'd only ordered two thousand, so I said, “Man, they're playing the hell out of the test pressing on BCN, maybe you should think about ordering some more!” I think they ended up selling about fifty thousand there.

DANNY GOLDBERG (U.S. press officer for Zeppelin, president of Swan Song in the U.S.) In the United States, there was a tremendous shift once rock radio became established. The power of critics was reduced by 50 percent overnight because people could hear music themselves, played by DJs who couldn't write and weren't so intellectual and weren't part of any group.

Zeppelin was the first big radio superstar in the rock world, which coincided with WBCN in Boston. They said they owed everything to J.J. Jackson. They didn't say, “We owe everything to Rolling Stone.” Whereas a couple of years earlier, the Jefferson Airplane would have said, “Thank God for Rolling Stone!”

JOHN PAUL JONES The first Rolling Stone review really did hurt, because it seemed spiteful. If we were crap and they said we were crap, well, fair enough. But we were really good, and we couldn't understand what the agenda was. Why didn't they like us? They could have said, “It's early days, and they'll do better next year.” But that review was total damning stuff, and we thought, “What's the problem?” It was galling, but at the same time you felt it was a shame that they didn't get it—that something was getting in the way of them getting it. So you had to have a defensive shield, and unfortunately a good defensive shield defends you against the good stuff as well as the bad stuff.

JOHN MENDELSOHN (reviewer of Led Zeppelin for Rolling Stone) I don't think anybody paid any particular attention to what I said. My review was a terrible piece of writing and a terrible piece of criticism—I thought Fusion's was very much better than my own. I'd never been a big fan of the blues. It was absolutely devoid of all the things I liked: melody, wit, vocal harmony. At the end of the first song when Robert Plant sang, “I know what it's like to be alone,” I thought to myself, “No, he doesn't.” He sounded sarcastic and glib, and it just really annoyed me. And that was the best song on the album.

MARIO MEDIOUS The moment they became successful, all the writers wanted to put down every fucking thing they did. That's what hurt Jimmy's ego. He would say, “Fuck those guys, they don't even play, they can't even write a note, so what the fuck does that mean?” I always said to him, “You can't read your reviews and worry about them—the fans are the most important thing.”

DANNY GOLDBERG Jimmy, particularly, was stung by Mendelsohn's review. There was this generational gap opening up. You had critics who were twenty-three to twenty-five years old, and suddenly they were feeling their mortality. There were these teenagers who were experiencing music in different ways and didn't care so much about what had been cool in 1965. Personally, I never identified with the most opinionated Rolling Stone critics. I was always a bit of a populist. I didn't have the rigid critical ideology.

RICHARD RIEGEL ('70s writer for Creem magazine) A lot of us really got involved in the blues that the English bands had taught us in the '60s, and—like the way the Animals taught it—we thought the blues should get more bluesy and more black all the time. And Zeppelin come along and not only steal the blues musicians blind but erect this super-blues skyscraper that's as white as possible.

ROY CARR (writer for New Musical Express) Led Zeppelin made it without anyone saying, “I've just seen the future of rock 'n' roll, and its name is … ” The American writers then were totally different than the ones over here. They thought they owned the bands.

JOHN MENDELSOHN My understanding is that my Los Angeles Times review of their live performance at the Rose Palace in Pasadena was more upsetting to them. It was one of those things where the audience was going crazy, and I thought it was excruciating. So they objected to the fact that, in my review, I didn't acknowledge how much the audience loved it. Which I don't think is necessarily the job of a review.

Robert Plant famously threatened me from the stage of the Anaheim Convention Center. I was told by several people that they announced one song by saying that if they got hold of me, they were going to make cauliflower out of my ears.

JIMMY PAGE Before they saw us in America, there was a blast of publicity, and they heard all about the money being advanced to us by the record company. So the reaction was, “Ah, a capitalist group.”

JUNE HARRIS BARSALONA I think maybe some people felt that the group was selling out. Looking back, it was sour grapes and resentment. You're not playing music so that you can't afford to get on a plane to go to your next gig; you're playing music so that you have a million-selling album. Come on! It was all about money, it was just that it was very unchic to say so. Bill Graham used to say, “It's not about the money; it's about the money.”

BILL GRAHAM (San Francisco rock promoter) Woodstock told industrial America, “Ah ha!” [It] said, “What is that tidal wave? Big business! My God, look at the money there.”

PAMELA DES BARRES It might have been very different had they got good reviews in the beginning. They might have been more open to the press and more open to everybody else. But then it wouldn't have become such a strangely dark and enigmatic band.

ROBERT PLANT The press themselves were a completely different animal. They were beer-swilling, monosyllabic guys who reviewed gigs from the beer tent. I don't think Nick Kent had surfaced, and Lester Bangs and those guys in America—the real poets, if you like—weren't involved in what we're talking about here.

MICHAEL DES BARRES I always think of David Lee Roth's remark that the reason critics loved Elvis Costello was that they all looked like him. A great metaphysical observation.

PHIL CARSON The band never had an issue with the British fans. The British journalists were a different story. That was the war that developed, because the journalists never got it. Almost as one, they started a campaign against Zeppelin. You know, “They're big in America, so what?” It was the self-aggrandizement of journalists who wanted to knock something down so they could look good, but they were manifestly wrong.

BRAD TOLINSKI (editor-in-chief of Guitar World) I don't think the critics understood them then, and I don't think they understand them now. There are people so caught up in the Zeppelin myth that they haven't taken time to understand the music.

DAVE LEWIS (publisher of Zeppelin fanzine Tight But Loose) I remember Charlie Gillett once inadvertently took on the might of Peter Grant. He wrote a piece in the NME about singles and Led Zep's resistance to them. Grant misread this as criticism of his boys and wrote a complaining letter in the following week's issue. With typical candor, Charlie replied, “Perhaps Led Zeppelin would like to tell me what they would like written about them.”

MICK FARREN (singer with the Deviants and writer for the underground press) The whole intimidating thing with Zeppelin was like something out of Performance. It was like the romance between the Krays and rock 'n' roll. Jonathan Green wrote a bad review of Led Zeppelin II in Frendz, and Grant calls up and says, “I expect you use your fingers for typing, doncha?” He's obviously sitting around in his office with nothing better to do that afternoon, so he calls up and hassles this poor overweight Jewish underground writer. Give me a fucking break.

CHRIS WELCH Word didn't filter back from the States as quickly as it would do now, so I wasn't as aware of the hostility of American critics toward the band. But I used to wonder why Zeppelin were so anti the American press. The critics over there probably didn't realize they'd paid their dues and come up through the pubs and clubs. It was as if the music was a fait accompli, somehow.

CHRIS CHARLESWORTH (writer and New York correspondent for Melody Maker in the '70s) They were nicer to Chris Welch than to anybody else, so they got him inside from the very beginning and took him to America to see them play at Carnegie Hall.

CHRIS WELCH We were in the Hilton on Sixth Avenue, and when I woke up the next morning, Jimmy asked if I'd had a good night. I told him I'd just sat in my room and watched television. Turned out they'd arranged to have some hookers and porn films and whips delivered to my room, but the girls had been stopped by the house detective before they got up to my floor. I mean, I barely knew what the word hooker meant. Jimmy looked very disappointed.

CAROLINE BOUCHER (writer for Disc and Music Echo) Personally I always looked forward to interviewing them. They were easy, and they were approachable, amenable. I would have a nice meal with them, and they would seem gentlemanly, lovely, nice. We used to hang out at the Golden Egg on Fleet Street. It was the only place you could eat, a terrible old dump.

I remember one interview with Plant. We must have come out of 155 Oxford Street and gone down Carnaby Street for a coffee. And he saw this beautiful sort of see-through shirt. So we went into the shop, and he didn't have any money on him. He said, “Can I have this, please? I can pay you by check.” And the shop assistant said, “We don't take checks. Have you got any ID?” So he went and got the first Zeppelin album and took it to the front of the shop.