10

Every Inch of My Love

He's like a huge golden lion conquering me. My legs cling around his waist as we rise and grind into each other.

—Lucille's fantasy about Robert Plant, in Fred and Judy Vermorel, Starlust: The Secret Fantasies of Fans (1985)

BP FALLON (U.K. press officer for Zeppelin, 1972–1976) A lot of bands sing about sex, but Led Zeppelin made sexy, horny music. It is sex. But it's never crass, it's always tasteful.

BILL CURBISHLEY (manager of the Who and later of Jimmy Page and Robert Plant) Zeppelin was really about sex, and the Who was more about intellectual frustration and aggression.

MICHAEL DES BARRES (singer with Swan Song band Detective) Jimmy leaves the Yardbirds and hooks up with this blond teenager who just epitomizes Viking Tolkienesque elfish mythology, all that Celtic magic—a high priest of the blues singing about Mordor in velvet pants. Fuck me! It was an incredible potpourri of influences and so sexy. Jimmy cast that band like a good director.

MARIO MEDIOUS (Atlantic Records promo man, 1965–1972) After Zeppelin played the Fillmore East, Iron Butterfly had to wait two hours to let the people cool out. Led Zeppelin was a motherfucker on that first show, man. They killed me, Jimmy pulling out that fucking bow and shit. Robert rocking around and screaming and carrying on, with his big old balls down there showing in his tight jeans, all the little chicks around him with their mouths wide open. I went back to Ahmet and said, “Man, they blew the fucking place away.”

BEBE BUELL (groupie and girlfriend of Jimmy Page's) You didn't hear Led Zeppelin on the radio; you heard about them from the boys in your class. Usually, it was the little girls who understood first, but in this case, it was not like when you came to school and asked your girlfriends which Beatle they liked best. It was driven by testosterone. I don't know if the music was designed to give boys power and sexual prowess, but I do know that when boys listened to it, they would become extremely cocky and full of themselves.

JAAN UHELSZKI (writer for Creem magazine) They became these proto-alpha types. Men aspired to be them, and women aspired to be with them. They used to say that Hendrix onstage would make every woman feel like she'd been raped—and had liked it, which is such a misogynistic thing to say—and Zeppelin made misogyny work for them. It was sex, but it was beyond sex.

To this day, I still feel emotional about Led Zeppelin's sound. When you think about the equation of sex plus drugs plus rock and roll, the drugs were the least interesting part of it. In fact, they didn't need the drugs because the other stuff was in place. And then when they had that dark stain of the bad things happening, that only added to it, which was the whole occult part.

BEBE BUELL Nobody in my group paid much attention to Plant; it was all about Page and Bonham. Even though we'd had Hendrix and Clapton thrust at us, Page and Bonham had an extreme and unique musicianship that had not been seen by too many people.

JAAN UHELSZKI There was something fragile and almost china doll–like about Page. I mean, you think about him later, and to even imagine that he was unthreatening is pretty naïve. But I guess it harkens back to that whole doe-eyed English masculinity that we all responded to. Back then, he was like the template for English male beauty for teenagers. With Page, it was that mystery, whereas Robert was bigger and in a way more like an American man—he was more obvious. You were either a Jimmy girl or a Robert girl; it was almost polarized along Lennon and McCartney lines.

PAMELA DES BARRES Jimmy was the perfect British rock star, with the red lips and the pale skin. For a woman, androgyny is like embracing yourself. There's a safety there, even though the danger comes along with it. They understand you. You can share lip gloss. You can primp with the same hair products and wear the same clothes. Jimmy would leave town and give me his clothes that he'd been wearing, and they'd fit. And he created romance in his relationships. He was totally all-encompassing in his lovemaking, so that you were absolutely lost in him. He knew exactly what he was doing. Incredible manipulator of the senses, the emotions, all that stuff. It's pretty sadistic, when you think about it now, but he wanted us to believe the fairytale. I remember Bonzo backstage, saying, “I wouldn't be surprised if I see you in Pangbourne”—Jimmy's actual English world.

MARILYN COLE (wife of Richard Cole) In Italian, they call it affascinante—it's a word that mixes “fascinating” and “charming,” and that's what Jimmy was. When you were with him, he was never one to look over his shoulder. His whole attention was on you. For that half an hour or whatever, you were enveloped, you were wrapped in gossamer.

MICHAEL DES BARRES Robert was Marilyn Monroe, and Jimmy was Hedy Lamarr with a Les Paul.

MAC POOLE (Midlands drummer and friend of Bonham's) Bonzo used to take the piss out of Percy. He'd say, “It's alright for you, you big fairy, running around getting all the glory; I'm the one doing the fucking work.”

PAMELA DES BARRES They were still men and loaded with testosterone, whether or not they wore lip gloss. They're still doing their manly thing, which is wanting more women than they could possibly copulate with.

GYL CORRIGAN-DEVLIN (friend of Page's and Plant's; traveled on Zeppelin's 1973 U.S. tour) When Charlotte Martin came along, in our minds it was a little bit like the Yoko-and-John thing. As beautiful as she was, she sort of took Jimmy away from us, and we didn't like that. We felt we were a family at that point.

PAMELA DES BARRES Jimmy met Charlotte literally on his birthday one week after Christmas 1969, and I heard about it and thought, “This can't be true.” But he stopped calling, and when they came to town, he invited me up to his room at the Hyatt House to tell me about it. It was the most gentle explanation of how he'd fallen in love and was going to settle down. He just wanted to let me down easy, which I think was incredibly rare in the world at that time.

• • •

RICHARD COLE (Zeppelin's road manager) They'd played all the major starting venues in America, but the response wasn't covered in England. And then when we came back, we did a whole range of small venues like Klook's Kleek and Cook's Ferry Inn, and they were sold out within minutes.

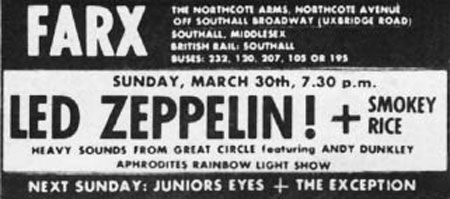

At the Farx Club, Southall, March 1969.

MAC POOLE John called me and said, “We're down at the Farx Club in Southall,” which was a pub where all the blues boys used to get together. Zeppelin had just done the first tour in America, and here they were back in England in a pub.

JIMMY PAGE When we did shows in England, they were always the shows that the press would come to and your family would come to, and there was that worry about dropping a note, and it was silly, but you go through that. We discussed those aspects of it. But when we went out to the States, we didn't give a fuck and became total showoffs.

ROBERT PLANT Led Zeppelin II was recorded and written mostly on the road, with the idea of using acoustics and developing much more of the textural part of the Led Zeppelin thing. Because if we weren't careful, we were going to end up like Grand Funk Railroad or the James Gang—sort of two-dimensional.

JIMMY PAGE People couldn't get enough of us, so we started touring on the strength of the first album, and it was tour after tour after tour of America. In-between time, we fitted in a small amount of recording at Olympic, where we did “Whole Lotta Love” and a couple of others, and the rest of the second album was recorded and mixed with Eddie Kramer in New York, and that was that. And we were still touring.

JOHN BONHAM There was an urgency to being in the States. I remember we went out to the airport to meet our wives, got them back to the hotel, and then went straight back to the studio and did “Bring It on Home.” We did a lot that year like that.

EDDIE KRAMER (engineer on Led Zeppelin II) I think they'd cut some tracks in England and one in Vancouver. They traveled around with this bloody great steamer trunk full of all the tapes, and they schlepped that thing around from pillar to post.

They called and said, “We're coming to New York, and do you want to do it?” I said, “Absolutely.” We had to cut more tracks, which I did at Juggy Sound, a tiny little studio that had opened in the '50s. We booked A&R Studios to do the overdubs and to do the mixing, so I think we spent maybe a day or two there. I don't remember precisely how many days, but Jimmy overdubbed some of his guitar parts with his little Ampeg amp. I know I did a tremendous amount of editing, for instance on “Moby Dick,” which was cut together from two or three different studios.

Page and Plant during a session for Led Zeppelin II, Los Angeles, spring 1969. (Chuck Boyd)

We mixed the album in two days over a weekend, and the results speak for themselves. It's a lovely sounding record, and it set the standard for them for many years to come. That's due to the fact that it was mixed at A&R all in one go, and Jimmy had a particular clear-headed vision about what it should sound like. With “Whole Lotta Love,” it's all true about the instinctual moment of both reaching for the reverb sound button or knob to put the reverb on to finalize that little mistake that we all laughed about.

JACK WHITE (singer, writer, and guitarist with the White Stripes) When I was very young, there was a girl down the street who had a tape with “Whole Lotta Love” on it. And I rewound it so many times that there was a fuckup on the tape before the guitar solo. I still think that break is probably some of the greatest guitar notes ever played, if not the greatest. Just that little section is so powerful, and it was powerful to me when I was five years old.

ROBERT PLANT Jimmy's riffs are the things that everybody goes nuts about. His capacity and ability to take teeny-weeny bits and develop them into huge anthemic moments was stunning. He had great diligence and a big, big gift.

BURKE SHELLEY (bass guitarist with Budgie) Page's sound wasn't that big—a quite scratchy sound, a lot of it. It wasn't really thick and huge, but it was all punched-out, you know.

BRAD TOLINSKI (editor of Guitar World) Everybody thinks Jimmy's guitar sound is big, and it's actually on the small side, to allow room for the drums to breathe and the bass to breathe. It's the nerdy, technical detail that makes this stuff great and makes it sound contemporary. Put on Beck-Ola or the other Jeff Beck records from that time, and those things sound awful. Then put on the first two Zeppelin albums, and they sound like something that could have been made last week. It's the overwhelming quality and bigness of the production that sucks you in—and the actual beauty of all the different sorts of guitar sounds.

HENRY SMITH (roadie for Led Zeppelin) Bonzo is one of the few drummers, to this day, who plays drums like an instrument. He doesn't just play drums to hear the sound. I could listen to him play by himself and be totally enchanted by what he was doing. He took a lot of rhythm 'n' blues drum licks and put them into rock—which at the time was different. Many times, he would turn and look at me with that little smirky smile, as if to say, “I pulled that one off!” And I would think, “Where did you hear that in your brain to even attempt it?”

SIMON KIRKE (drummer with Free and Swan Song band Bad Company) I've played drums for nearly forty-five years, and to this day I can't figure out some of the stuff he does.

TERRY MANNING (engineer on Led Zeppelin III) Bonzo loved Gene Krupa, and in my opinion, Bonzo was playing the hardest jazz ever, as simply as anyone ever did. He really wasn't bashing like a rock drummer. There was finesse to the bashing, if that makes any sense—hitting hard but with incredible time and feel. He's setting his own tempo, and the others had to follow it. He is more of the percentage of the total sound and production and feel of that band than any drummer in any other band. He made the drums important all the time.

Jimmy once said to me, “Our time is different, and I don't think the general public or other musicians will ever get what we do or catch up to it.” Maybe that sounds egotistical, but I don't think it is. You hear so many other bands that tried to sound like that and had the Robert Plant hair and everything, but none of them had their own sound.

GUY PRATT (bassist with Page's post-Zeppelin band Coverdale/Page) There is stuff that Jimmy does that as a musician you just can't count. Under no circumstances look at his legs. Look at anyone else's legs, and they are tapping time. Jimmy's legs give you no clue.

EDDIE KRAMER I did “Ramble On” at Juggy's. I'd have to listen to it again, but it was something very silly and spur-of-the-moment. Whether it's Bonzo's knees or beer cans or his head, I can't remember.

ROBERT PLANT By then, I had developed a wanderlust, and that song was really just a reflection of myself.

PAMELA DES BARRES Robert was so young and innocent. Singing about all these groovy fairy things with that crazy heavy music—it's an outrageous combination, so it just all fit and worked and touched the girls with his sweet words and that dangerous dark scary shit that Jimmy was doing. The dark and the light.

ROBERT PLANT During the making of Led Zeppelin II, we went to the old Del-Fi and Gold Star studios in L.A. We were always on that trail.

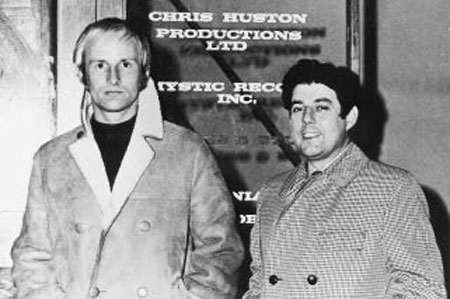

KIM FOWLEY (L.A. producer and scenester) Del-Fi was at the corner of Selma and Vine. The studio had been bought by a genius engineer called Chris Huston and renamed Mystic Sound. There was a bank next door, and allegedly they would use the empty bank vault or hallways for that tremendous echo.

CHRIS HUSTON (owner of L.A. studio Mystic Sound) We did the tracks live, with Plant standing in the middle of the room with a hand-held microphone. You can hear that at the end of “The Lemon Song,” where Plant sings, “floor floor floor”—that echo was recorded in real time.

Chris Huston and engineer Doug Moody outside Mystic Sound Studios, Los Angeles, in 1968. (Chris Huston Collection)

MARIE DIXON (wife of Chess blues legend Willie Dixon) Around 1979, my late daughter Shirley discovered the recording of “Whole Lotta Love” at a friend's house on the North Side. She was convinced it was one and the same thing as my husband's song “You Need Love.” Willie had a publishing company, Arc Music out of New York City, that was supposed to monitor it. You would think they would have been on top of that, but they didn't care. He was pretty happy that they'd recorded “Bring It on Home,” never knowing they would take another song that wasn't popularly known and give a new title to it.

DON SNOWDEN (biographer of Willie Dixon) Willie would never have heard “Whole Lotta Love” because he wouldn't have been listening to a rock station, and his management people would never have heard the Muddy version of “You Need Love” to make the connection. And almost no one knew of “You Need Love,” because it had only been on an early '60s Chess single in the U.S., before us white kids knew blues existed.

What I remember finding out is that both “You Shook Me” and “You Need Love” did come out on an EP in England or Europe in 1962, and that's almost certainly where the Zeppelin crew would have heard it. Giorgio Gomelsky said Willie was leaving taped copies of songs with him in 1963, during the first American Folk Blues Festival gigs in the U.K., and it's hard to believe that Page wasn't part of that circle, given the Yardbirds connection.

The Small Faces' version is credited to Marriott-Lane but is almost identical to the sound of the Muddy track with the organ—not to mention throwing in a verse's worth of “Land of 1000 Dances.” Plant really copped Marriott's vocal stylings as his launching pad. Poetic justice, I suppose.

STEVE MARRIOTT (singer with the Small Faces and Humble Pie) “Whole Lotta Love” was nicked off our album. We did a gig with the Yardbirds, which Robert was at, and Jimmy Page asked me what that number was that we did. “‘You Need Loving,'” I said. “It's a Muddy Waters thing.” Which it really is, so they both knew it. After we broke up, they took it and revamped it. Good luck to them. It was only old Percy who'd had his eyes on it. He sang it the same, phrased it the same; even the stops at the end were the same. They just put a different rhythm to it.

ROBERT PLANT Page's riff was Page's riff. It was there before anything else. I just thought, “Well, what am I going to sing?” That was it, a nick, now happily paid for. At the time, there was a lot of conversation about what to do. It was decided that it was so far away in time and influence … well, you only get caught when you get successful.

JEFF BECK There was a lot of conniving going on back then: change the rhythm, change the angle, and it's yours. We got paid peanuts for what we were doing, and I couldn't give a shit about anybody else.

ED BICKNELL (former manager of Dire Straits) Mick Jagger famously said, “We had the best of Chess”—in the sense that they'd pinched everything and not paid for it. The same went for Zeppelin, because both Mick and Jimmy found the idea of money going out to be really quite traumatic.

ROBERT PLANT Keep your head down and don't say anything, ha ha ha! If you read Deep Blues by Robert Palmer, you'll see that we did what everybody else was doing. When Robert Johnson was doing “Preaching Blues,” he was really taking Son House's “Preacher's Blues” and remodeling it.

JOHN PAUL JONES I don't know, the whole question of the appropriation of black music by white musicians is just so … the whole thing is that nobody really owns any music. There's a lot of white church music in black music. Anybody who can make music is affected by what's going round. They're all materials to be used—to make more music.

CHARLES SHAAR MURRAY (writer for New Musical Express in the '70s and '80s) Nick Kent told me that when he did his first-ever Jimmy Page interview, he raised the point that many alleged Page-Plant songs—notably, “Whole Lotta Love,” “Bring It on Home,” “The Lemon Song,” “Black Mountain Side,” and “In My Time of Dying”—are either traditional or else straight lifts from the likes of Willie Dixon. Page got extremely defensive.

NICK KENT (writer for New Musical Express) People like Charlie Murray didn't like Led Zeppelin and were morally offended that they stole songs from his old blues heroes. He didn't get that blues is a very malleable form, and one way of customizing it isn't necessarily irrelevant or sacrilegious.

MARIE DIXON Willie took Atlantic to court. There was a settlement out of court, but there was no significant money to Willie from record sales. He went to his grave feeling that he was not represented properly. You probably read somewhere where it was seven million dollars, but none of that happened. Not one million, not close to one million. It was very disappointing to Willie, but he said he didn't have time to be angry with people. He never carried any bitterness. I believe he passed away as a very happy person.

JIMMY PAGE I don't know what the outcome was. I haven't made any court appearances, personally. I don't know. I mean, I might know. It's probably on file somewhere. I'm just not interested. You should ask Robert these things, because I didn't write the words, did I?

PAMELA DES BARRES I remember sitting in between Jimmy and Robert. Led Zeppelin II was about to come out, and they were working on the order of the songs. I was just sitting there, knowing that history was being made and I was right in the middle of it.

EDDIE KRAMER One has to think of Zeppelin II as a watershed moment. It took the world by storm because, sonically, nothing had been done like that before. It was an amazingly powerful record. Even today, though it doesn't have the sonic depth of what we can do now, it still kicks everybody's ass.

There are a few reasons, I think. One, the band was very united, and all the musicians thought as a unit. Two, the immense power of Bonham's drumming, which drives the whole thing. Three, Page is brilliant in terms of his direction and interpretive qualities, and he's got this amazing ability to absorb all these influences—blues, British folk music, and all that stuff—into one cohesive whole. Four, John Paul is the mastermind behind the scenes, sewing it all together. And five, Robert's voice and his lyrics—you don't get a better combination in rock 'n' roll. It was the dark star of the rock world, in a positive, not a negative, way. Immense power.

It's more than just the sound. The ability to go from extremely quiet low dynamics to an immensely powerful rush of noise carries a tremendous amount of weight. Plus, you've got the huge sexuality of Robert—he's up front doing his thing. It's like a panty-wetter all night.

PHIL CARSON (head of Atlantic Records in the U.K.) I remember putting on the acetate of the second album and the sound of “Whole Lotta Love” just erupting from the speakers. I was scared to death by the middle section, thinking, “What the hell is going on here?”

CHRIS WELCH (writer for Melody Maker) Phil Carson had been a supermarket manager before playing bass with the Springfields. I think he was working for MGM-Verve when Ahmet hired him to be head of Atlantic in the U.K. I think he would love to have been Zeppelin's manager. He was always a little bit in the footsteps of Peter.

PHIL CARSON It was Nesuhi Ertegun who actually hired me. As an ex-musician, I of course knew who Jimmy and John Paul were from the session circuit, but I'd never worked directly with them. When I got the job, I think they were relieved that someone they knew had been a musician had got the job as their day-to-day guy.

“The ears and eyes for Nesuhi and Ahmet”: Phil Carson with Zeppelin, backstage at the L.A. Forum, September 4, 1970. (Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images)

ROY CARR (writer for New Musical Express) People liked Phil, whether it was the Stones or Zeppelin. He never bullshitted anybody, and he was always ready to muck in. He wasn't sort of, “I'm from the record company”; he knew all the musicians.

MARILYN COLE Phil was really sharp, no messing about. He and Peter had a great respect for each other, and both of them had huge respect for Ahmet. Carson was good with people; he knew how to work relationships. With all the madness that was going on, he kept his ground. He was a character, like Ahmet and Peter were characters. After these guys, the business was just run by accountants.

MIKE APPLETON (producer of BBC's Old Grey Whistle Test) Phil was the eyes and ears for Nesuhi and Ahmet. The thing about him was that he didn't mind being used by bands. He didn't see that as demeaning. He accepted that it was part of the job to run around after them. It was one of the cogs that drove the machine.

PHIL CARSON They used to forget that I was the record company guy. Richard Cole had a stamp made up that said, “Atlantic Records will pay.” And he would just stamp any bill at the Speakeasy. So I had my own stamp made that said, “Charge artist.”

JERRY GREENBERG (general manager of Atlantic Records, 1969–1980) In America, “Whole Lotta Love” was getting played like crazy on FM stations, but it ran five minutes or something. I called Peter, and I was like, “Can we get Jimmy to do an edit? I think I can get play on some top 40 stations, but they're not going to play a record that's five minutes long.” He said, “Greenberg, he's not going to do it.” I said, “Well, what if I do an edit and you approve it?”

PHIL CARSON After we put “Whole Lotta Love” out, I received this irate phone call from Peter: “ 'Ere, we don't do singles.” So I was summoned to his office, and I said, “But this is how you promote records.” “Not Led Zeppelin records you don't.” I was told I had to withdraw them. I think about three thousand got out.

ROY CARR Everybody had hit singles, and Zeppelin didn't. If you said, “Led Zeppelin,” people would say, “Whole Lotta Love.” But that was it, unless you were a devoted fan. Whereas with the Stones, the Who, you could rattle off the singles. This whole thing of not releasing singles made them a bit more mysterious.

• • •

PHIL CARSON The first time I met Steve Weiss was at Madison Square Garden, where he physically threw someone out who was serving him a writ.

CHRIS WELCH Steve met us at Kennedy airport and got in the limo with us. He said, in a very Bronx-type accent, “I just heard the new album, Jimmy, it's a masterpiece.” And Jimmy said, “Don't gimme that New York bullshit.” I was in awe that anyone would dare speak to an American lawyer like that.

SAM AIZER (artist relations, Swan Song in the U.S.) In the Atlantic archives, there's a picture of Page, Beck, Peter, and Steve Weiss standing together. Peter is wearing a suit, he doesn't have a beard yet: he's a businessman from England wearing the only suit he owns. Meanwhile, Steve is dressed up like Jimi Hendrix, with, like, a sash and a vest and long hair. You look at it and think, “This guy must be in the band.”

SHELLEY KAYE (assistant to Steve Weiss) I remember Steve going to a meeting at Madison Square Garden in a lime-green paisley suit. It was hilarious. Actually, it was pretty atrocious by today's standards.

JANINE SAFER (artist relations, Swan Song in the U.S.) Steve didn't look like anybody in New York. He was a short man, skinny as a rail, and he wore tight blue jeans with a big old honkin' Texas cowboy belt, Nudie shirts with sequins, cowboy boots, and this huge mane of silver-flecked hair.

SHELLEY KAYE He and I used to fight a lot. We would get into it and have some real arguments, because he just drove me crazy sometimes. But he was a very, very smart guy. He got the business side of it.

JOHN PAUL JONES The main thing I remember is that we worked like dogs. We didn't stop working, right the way through 1969 and 1970. There was constant touring.

RICHARD COLE You could only work New York, Boston, Detroit, Chicago, Cleveland, and maybe pick up a date in Texas. And then you usually had to go out to the West Coast to do L.A. and San Francisco, and that was your whack. Plus, you could only do weekends. So it could take six or seven weeks to do a tour.

JOHN PAUL JONES People were going to sleep onstage, especially in America. You'd see bands sort of wandering around looking at each other and saying, “What shall we play next?” And we just came onstage and went blam-blam-blam, three or four numbers, and people sat up in shock. You didn't notice that there wasn't a set as such, because the power came from the music.

A lot of people say to me, “You can just see the communication onstage…. Why isn't my band like that?” Our priority was to make Led Zeppelin sound great, and if that meant playing two notes in a bar and shutting up for a bit, then that's what it took. You had the big picture in your mind and in your ears all the time.

JACK CALMES (cofounder of Showco sound and lighting company) We did a one-off using the Showco sound system with Zeppelin sometime in May 1970, and afterward, Robert Plant said, “Fuck, I hate these systems we're using. What about those guys from Texas?” We picked up their tour in the summer of 1970 and were never away from them after that.

JOE JAMMER (Chicago blues guitarist and Zeppelin roadie) In those early days—before Charles and Henry made the scene—the band was just drinking. Bonham was drinking the most. You had to keep up with him. He was the regular guy who'd smack you on the back so hard, it would knock you forward.

BILL HARRY (Zeppelin's first U.K. press officer) I was at the Revolution club one night, and I got a call from Bonzo. He said, “I want to come down and have a drink with you.” I said, “Where are you?” He said, “Birmingham.” I said, “You must be joking. The club shuts at two o'clock.” Ten to two, he arrived. I said, “The bar shuts in ten minutes.” So he ordered fifty lagers.

MAC POOLE Bonzo hated the fawners and hangers-on, even in Birmingham. I remember this agent came into a club one night and did the big, “Hey, John!” because he'd heard Zep had made a few quid. John just went, “Fuck off!” and smacked him on the nose. This was a guy who'd always kept hold of the money and never paid anybody. And we all applauded John. The guy got what he deserved.

SHELLEY KAYE Bonzo was very gregarious and very happy. He wanted to sleep with me, and I wasn't interested. I knew they were married, and I was never a groupie. In those days, sexual harassment was not a defined term. Plus, it was just different then. It was a much more innocent time.

ELLEN SANDER (rock writer for the Saturday Review and other publications) There was always a bit of tension. It's not easy having an embedded journo and photographer. And a female journo was not a good fit for them, as it turned out. I got on great with Peter Grant and spent some extremely pleasant social time with him and his wife. I remember them fondly, but Richard Cole was a pain in the ass.

PHIL CARLO (roadie for Bad Company, tour manager on the last Zeppelin tour) The whole groupie thing was massive. The proper ones—Penny, the Flying Garter girls, Sweet Connie from Little Rock—were the nicest people you could come across. You'd trust them with your life, and they'd look out for you as well. You'd see them year after year, and there was a mutual respect. I remember Penny Lane, who was the head Flying Garter girl, saying to me, “This is bizarre. We have letters of application from girls all over America with a CV.” It was like a corporate business.

“SWEET CONNIE” HAMZY (Arkansas groupie of wide renown) Groupies went back all the way to Sinatra. Power and glamour have always attracted women. When you're a teenager, you're either a cheerleader or in a school band or on the football team, and a lot of people like me didn't fit into any of those molds. So I decided to become a groupie because all those people—the cheerleaders and all of them at my school—thought they were so cool, and I thought I'd show them what cool was really about.

Miss Pamela was, like, the first. She led the way and paved the way for the Butter Queen and then Cynthia Plaster-Caster, and I sort of followed in their footsteps. I decided I wanted to be one, and if I was going to do it, I didn't want to do it half-assed. I wanted to be one of the biggest ones I could be. No matter how many people I had to blow to do it.

PAMELA DES BARRES Led Zeppelin got to L.A., and it was literally like falling down the rabbit hole. Cynthia Plaster-Caster had a Zeppelin poster on her wall, and they were so gorgeous. She told me how dangerous they all were and how they had this terrible reputation of abusing women and just being wild.

HENRY SMITH L.A. had a mystique. It's warm, and when you get in the warmth, you kind of let your hair down. Drugs were easy to get, so when we arrived, it was like, “Okay, we've finished the gloomy part of the U.S., which is anything between Cleveland and Denver, where there's nothing to do.”

BIG JIM SULLIVAN (London session guitarist and member of Tom Jones' touring band) When I joined Tom Jones in 1969, every time we got to L.A. we'd always run into either Jimmy or John Paul or one of the lads. The first time I went to the Whisky, Jimmy and John were sitting at the table, and Jimmy was squirming about quite unnaturally. I looked under the table, and there was a girl there.

JACK CALMES Once, when they were playing Dallas, we put Zeppelin into the Cabana Hotel, and they got thrown out after two or three days. So we thought we'd rent them a house in the country. They were out at this ranch house, and it had a swimming pool, and all these groupies were out there with them. The Butter Queen was kind of like a madam, and they all had their tits out, riding on their shoulders in the pool. Barbara Cope was the Butter Queen's real name. She was a hound herself, but she was the organizer of the girls and would tell them what was needed.

At this point, the Christian owner of the ranch and his two little daughters pull up because they want to meet the band. So we all got thrown out of that place, too.

ROBERT PLANT I was twenty-one, and I was going, “Fucking hell, I want some of that. And then I want some of that, and then can you get me some Charley Patton and some Troy Shondell? And who's that girl over there and what's in that packet?” There was no perception of taste, no decorum. It was a sensory outing.

JIMMY PAGE There was a certain amount of hedonism that was involved, and why not? We were young, and we were growing up. People say, “I grew up to Led Zeppelin.” And I say, “So did I.”