11

In the Misty Mountains

I live for my dream, and a pocketful of gold.

—Led Zeppelin, “Over the Hills and Far Away”

JOHN PAUL JONES It was much harder to get anywhere in England. We toured England quite a bit and worked very hard, and the press kind of wasn't interested in us at all; 1970 was the first time we felt we got recognized for what we were doing. Up till then, it felt like we were big in America but not in England. Maybe the Albert Hall was the first “Here we are” type of show in England. Here was a band that could fill the Albert Hall, but where did they come from?

ROBERT PLANT It was an absolute shock when I saw the Albert Hall stuff on DVD. It's kind of cute and coy, and you see all that naïveté and the absolute wonder of what we were doing and the freshness of it, because the whole sort of stereotypical rock singer thing hadn't kicked in for me. I was just hanging on for dear life, really. I was playing and singing and weaving my way through the three greatest players of that time, and I was coquettish, coy, shy—a bit embarrassed, really.

RICHARD WILLIAMS (writer for Melody Maker in the '70s, later the paper's editor) I interviewed Robert in the back of a Rolls-Royce going to Heathrow, and we talked about the Buffalo Springfield and the Flying Burrito Brothers and all the West Coast music he loved. In the piece, I said something like, “Despite being the singer with this heavy group, he actually likes good music.” Not long after that, I saw them at the Albert Hall, and Jimmy Page approached me in the interval, with Peter Grant glowering behind him. Jimmy said, “Are you trying to break up my band?”

BILL HARRY (Zeppelin's first U.K. press officer) I only saw Peter appear frightening once, and that was backstage at the Albert Hall. There were some jobsworths who were saying, “You can't do this, you can't do that.” He appeared very frightening, and he terrorized them.

JACK CALMES (cofounder and head of Showco sound and lighting company) The first thing anybody would tell you when you went into Frank Barsalona's office in 1970 and you had a Led Zeppelin date was, “Watch out for Peter Grant. You'd better not have anybody selling T-shirts or taking pictures.”

ANDY JOHNS (engineer on Led Zeppelin II, III, and the untitled fourth album) I remember walking down the street with Peter, and he went, “Hang on a second, Andy, we have to go in here … got a bit of work to do.” And he went in, and they'd been selling bootlegs, and he was trying to stick something up the guy's ass, and it wasn't working because he had jeans on. So he wrapped it round his head instead.

CHRIS WELCH (writer for Melody Maker) I witnessed Peter destroying a bootlegger's equipment in Germany. The guy was outraged and fetched a cop, who took one look at Peter and walked away.

MARIO MEDIOUS (Atlantic Records promo man, 1965–1972) On those first tours, we'd be the first off the planes. All the guys who were driving the forklifts and picking up the baggage would call the band “fuckin' faggots” and shit. Robert was a big guy, he'd knock 'em the fuck out. I would go over and jump right in the middle of it, saying, “These guys are in first class, and you guys are driving forklifts, so what kind of shit is that? They can buy and sell your ass.”

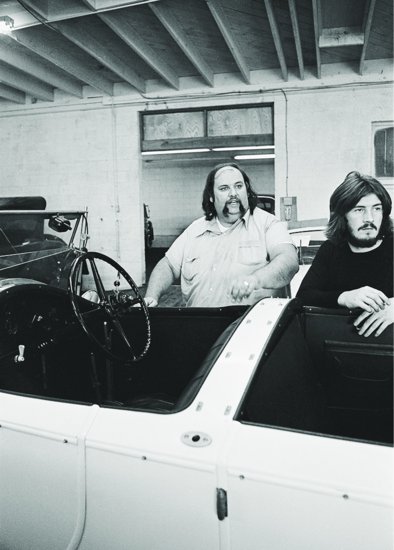

Grant and Bonham indulging their shared passion for vintage cars, Los Angeles, 1969. (Chuck Boyd)

JACK CALMES Nobody, other than Elvis, had ever chartered a plane before. Peter and the band wanted to base themselves in cities so they didn't have to get up early in the morning and fly to the gigs, so I found them a charter service that had a field in Dallas. The first one was a fan-jet Falcon that seated six, and there was a stewardess. God knows what they put her through on that little plane.

ROBERT PLANT The brutality of the police in the Southern states in the early '70s was unbelievable. In Memphis, the police brutalized the fans every time they stood up, so I did a Roger Daltrey spin with the mic and hit a cop on the back of the head. That caused a few problems. In those days, we regularly fell foul of paranoid prejudice. I was spat at in the face because I was seen as antiestablishment. We were always potentially in trouble in those areas, just by breathing.

TERRY MANNING (engineer on Led Zeppelin III) The manager of the Mid-South Coliseum in Memphis was a guy called Bubba Bland, who ran it with an iron fist and didn't cotton to those foreigners coming in there. As soon as “Whole Lotta Love” started up, the whole crowd was jumping and screaming—the piece was just throbbing. Bubba pulled a handgun on Peter behind the stage and said, “Make these people sit down, or I will cut the power and everything will be over.” So Peter called Robert over, and Robert went back to the mic and tried to calm everybody down. Then the band went into “Communication Breakdown,” and everybody was right back up again.

I went backstage at the end, and it was just Peter and Richard and the four guys and me. They were standing there in the dressing room, saying, “Man, America may be cute, but it's just not for us.” They had been shot at in Texas the week before, and their limo was actually hit by a bullet between Dallas and Fort Worth. I apologized on behalf of the city of Memphis and on behalf of the South, but they were very upset and never played Memphis again.

JIMMY PAGE It wasn't until the spring of 1970 that we actually had a real break. That break was only probably a couple of months, but to us it seemed an eternity, because we'd been going nonstop for eighteen months. Robert had this place in Wales that he'd been to with his parents in the past, and he said, “Do you fancy going down there?” I said, “It would do me a lot of good to get out to the countryside.” Robert's wife and his daughter were there, and Carmen was only nine months old at the time. It was quite a magical time all around.

JOHN PAUL JONES A lot of Jimmy and Robert's friendship came out of the fact that they traveled around together during times when we were not on tour. Whereas John and I went home to our families, they went off writing or whatever.

BENJI LeFEVRE (Zeppelin sound technician, 1973–1980) I think Robert and Jimmy realized they could make even more money than Jones and Bonzo, because they were the main writers. And that drove a bit of a wedge in there that pulled them closer together, which was why they used to go off on expeditions and try to expand their musical horizons.

Robert Plant returns to Bron-yr-Aur, September 18, 2003. (Art Sperl)

ROBERT PLANT [Bron-yr-Aur] had no power, no services, and was on the side of a mountain. It was usually pissing down with rain. We had beautiful women with us, one each, an old English army jeep outside, and a blue-eyed Collie. They'd just invented the cassette machine with speakers, so during the sexual act—with the women, not the dog—we could play the tape really loud.

CLIVE COULSON (Zeppelin roadie and tour manager for Bad Company) It was freezing when we arrived. We collected wood for the open-hearth fire, which heated a range with an oven on either side. We had candles, and I think there were gaslights. We fetched water from a stream and heated it on the hot plates for washing—a bath was once a week in Machynlleth at the Owen Glendower pub.

Me and Sandy [McGregor] were the cooks, bottle-washers, and general slaves. Pagey was the tea man. Plant's speciality was posing and telling people how to do things. No, everyone mucked in, really. I wouldn't take any of that superior shit. They were wonderful people to work for, normal blokes, they weren't treated as gods. I'm not sure who got the job of cleaning out the chemical toilet.

JIMMY PAGE It was one of those days after a long walk, and we were setting back to the cottage. We had a guitar with us. It was a tiring walk coming down a ravine, and we stopped and sat down. I played the tune [of “That's the Way”], and Robert sang a verse straight off. We had a tape recorder with us.

ROBERT PLANT In amongst it all, when Jimmy and I set off for the Welsh mountains, was the question, what sort of ambition did we have? And where was it all going? Did we want world domination and all that stuff?

We didn't really have anything to do with the Stones or the Beatles or anybody, but we went to Wales and lived on the side of a hill and wrote those songs and walked and talked and thought and went off to the abbey where they hid the Grail. We were letting ourselves in after dark to places of Celtic historical interest, and no matter how cute and comical and sad it might be now to look back at, it gave us so much energy because we were really close to something. My heart was so light and happy. It was the beginning of a new era altogether. At that time and that age, 1970 was the biggest blue sky I ever saw.

SALLY WILLIAMS (girlfriend of Bonham's drum roadie Mick Hinton) There was one time when they were at Olympic Studios, and there'd been a screw-up with the hotels. So Robert stayed the night in my flat in Holland Park. We sat and talked about Wales—because I was from Wales and he had just got his farm there.

I thought, “This is such a different person. I wonder how many people see that when he's prancing around onstage, when he's that god that everybody's adoring.” He was obviously well-read, and he knew more about Welsh mythology than I did. And then he said, “I think I'll turn in. I've got to go back in the studio tomorrow.” And that was it. A total gentleman.

ROBERT PLANT I was very content with the environment where I came from, though it never moved that much from the time of my late teens. The people around me that I knew were quite stimulating. They'd been to Afghanistan. They went across that route to India and came back with carpets in vans stuffed with bags full of dope. There was a subterranean condition all around the Welsh borders. There was a whole deal going down then that was really interesting.

HENRY SMITH (Zeppelin roadie) I remember staying overnight many times at Jennings Farm, which Robert bought in 1970. At that time, only three or four rooms were being used, because the others were being renovated. Robert had a goat called Major and a dog called Strider. Major used to come into the house like a dog or a cat. The only rooms that were really used were their bedroom, the kitchen, and this long, narrow room that had a little fireplace in it. That was where we would sit and listen to Moby Grape and Fairport Convention.

ROBERT PLANT By that time, we'd really become good friends with the Fairports and the Incredible String Band, and Roy Harper was on the scene. There was quite a lot of moving around, and it was interesting, really. The places the Fairports and the String Band were coming from were places we loved very much. The Zeppelin thing was moving into that area in its own way. It was part bluff and part absolute ecstasy—going from “You Shook Me” to “That's the Way.” I actually relaxed enough to start weaving a melody that was acceptable without it having to have that blues-based thing going on.

DAVE PEGG (former bandmate of Bonham's, bassist with Fairport Convention) When I joined the Fairports, we made an album called Full House, and I took the album over to show Bonzo because he'd given me the Zeppelin one, and I thought, “I've made it. I'm in a proper band now.” He phoned me up a few weeks later and said, “It's great, mate. I really like it.” I took Dave Swarbrick over, and we got there and Bonham said, “Listen to this, Peggy.” He'd got his son Jason a miniature drum kit, and he put Full House on, and Jason played along with it, and he got it all.

• • •

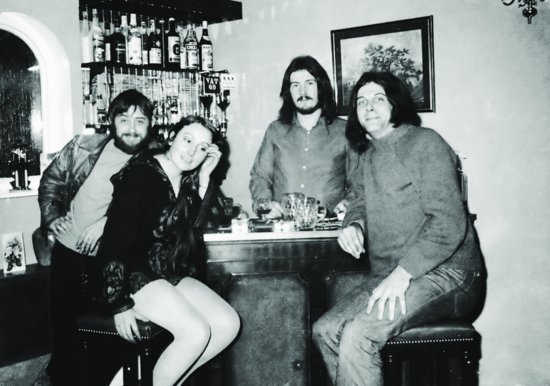

Bonzo behind the bar at West Hagley, with Fairport Convention's Dave Swarbrick (left), Swarbrick's girlfriend Vivienne, and Dave Pegg. (Courtesy of Dave Pegg)

ANDY JOHNS My brother Glyn got me a gig at Morgan Studios, which was this new tiny place in Willesden. There are two songs on Led Zeppelin II from Morgan, but they weren't the cool tunes. I must have done okay because next thing I got a call. I think Pagey enjoyed working with me because he figured he could control me.

HENRY SMITH Andy was a joy to work with. He was such a nice guy; it was like he was your brother.

ANDY JOHNS I suggested we used the Stones mobile, which was the first mobile in Europe, and I suggested going to Mick Jagger's house. Pagey is a wise fellow, and he doesn't like to expend money when he doesn't have to. “How much would that cost?” “Well, the truck's about £1,000 a week, and Mick's house is about £1,000 a week.” “I'm not paying Mick Jagger £1,000 a week! I'll find somewhere better than that.” So he found this old mansion in Hampshire, and we went down there, and it was somewhat seedy. There was stuffing coming out of the couch, springs coming out of the bed, but it wasn't a bad place. It had a nice fireplace, and I was bonking the cook.

Headley Grange, Hampshire, in 1973. (Richard Haines/Genesis Pictures)

RICHARD COLE Headley Grange was found by Peter's secretary Carol Browne, who used to read magazines like The Lady and saw an advert for it. I was dispatched down there to see if it was suitable and if it had enough rooms and if they'd be able to record there.

It was a bit damp and cold. Jimmy had a room right at the top that was haunted, I'm sure of it. They recorded in the worst fucking places imaginable, and I don't know whether it was because in the back of Jimmy's mind, he thought, “If I can make the outside surroundings as unpleasant as possible, they'll get on with it.”

ANDY JOHNS Pagey would come up with ideas that you'd never heard before. He was very much into tunings back then, and it really worked. It wasn't like he was in total control of the situation, because John Paul was just as great a musician as he was and would also come up with super ideas. But Pagey would spend more time in the control room with me.

JOHN PAUL JONES What happened with Zeppelin was very organic. We didn't feel a need to chill out, there was a need to chill out, and we did—we just didn't think about it first. You find yourself with a bit more time, and you sit down with some acoustic instruments, and you start exploring. Jimmy always had acoustic guitars around, and he often would play things on acoustic. To me, the riffs sound the same on acoustic as they do on electric; it's only the tones that change.

I'd bought a mandolin on tour in America, and I just started playing it. And as soon as I get an instrument, I want to start using it. And we were probably listening to more Joni Mitchell by then, anyway, plus, you know, people like Fairport. I probably learned my first mandolin tunes from Liege and Lief. Literally it was sitting around a fire at Headley and picking things up and trying things out. It was never, “Okay, we've done heavy, now we should look at soft.”

JONI MITCHELL (high priestess of L.A. singer-songwriters) Led Zeppelin was very courageous and outspoken about liking my music, but others wouldn't admit it. My market was women, and for many years the bulk of my audience was black, but straight white males had a problem with my music. They would come up to me and say, “My girlfriend really likes your music,” as if they were the wrong demographic.

ROY HARPER I remember “Immigrant Song,” “Celebration Day,” and “Since I've Been Loving You” being played at gigs. And they became staples of the Zeppelin set. “That's the Way” was probably Robert finding himself, right at the beginning of his own real writing. If you stand back and look at that album, it really is like their first record.

ROBERT PLANT “Immigrant Song” was supposed to be powerful and funny. I was in Iceland, for Christ's sake, and it was light all day, and it was a hoot. People go, “Led Zeppelin had a sense of humor?” But I guess with a riff as relentless as that …

KIM FOWLEY (L.A. producer and scenester) Led Zeppelin were both dangerous and spiritual. They get you with all that maudlin melancholy acoustic music and all the mythical stuff from Wales, but then they have the Willie Dixon–derived blues stuff going on at the same time. The mystery kept people coming to the live shows, and they got to read meanings into the lyrics that weren't there. It was brilliant management. Peter Grant was a genius.

NICK KENT (writer for New Musical Express) Zeppelin had mainly been playing in America, so the Bath festival was very important. They knew they were going to get a big crowd, and they wanted to show that they were now one of the biggest groups in the world.

PETER GRANT Bath was a turning point in recognition for us…. I remember Jonesy arriving by helicopter with Julie Felix and Mo, and we had to get the Hell's Angels to help us get them on site. I'd made contact with the Hell's Angels in Cleveland with the Yardbirds, so we had no bother with them.

ROY CARR (writer for New Musical Express) There were so many big names at Bath—Zappa, Pink Floyd—but Zeppelin came on and it was one of those magic moments where a band just connects. They seemed to have all the dynamics you'd expect from an American band. They were just on fire.

NICK KENT When you went to festivals, if the Who or Led Zeppelin were on the bill, the other groups pretty much might as well not have turned up. I mainly went along to see all the West Coast bands, and most of them were very disappointing because they couldn't project. They would lock into themselves and just sort of jam. Led Zeppelin were all about projecting; they'd worked it out.

AUBREY POWELL (sleeve designer for Zeppelin albums from Houses of the Holy to In Through the Out Door) I looked down from the stage at dusk, and everywhere there were little campfires with people wandering through the crowd like ethereal fairies. It was a mystical gathering of tribes, exactly as they describe it in books. Suddenly, Zeppelin come onstage and it's BANG!! Jimmy's there in his long coat and farmer's hat, and I'm going, “Fuck!” It was so cool that this brilliant guitarist was wearing that old overcoat.

ROY HARPER I was asked to go to Bath by the guys running the festival to help fill out the bill. While I was in the general backstage area, a guy approached me and asked me whether I could play “Blackpool,” an instrumental track from my first record. When I'd finished, he thanked me and made complimentary comments. I didn't think that much about it, except I thought the pants he was wearing were too short.

About an hour after I'd played, a band came onto the stage and were tuning up and getting ready to play. I recognized the guitarist as the man who'd asked me to play the instrumental, although he was now wearing a gray tweed overcoat and a hat. The first song was very powerful, but the third song pinned me down. It was “Dazed and Confused” and it was incredibly moving, particularly because I began to realize that most of the young women around me were standing up involuntarily, with tears running down their faces. They couldn't help themselves, and neither could I.

I immediately recognized that I was at a world event. This was going to be planetary. There was no way that young people everywhere were not going to be forever attracted to this.

ROBERT PLANT Somebody had to have a wry sense of humor and a perspective [that] stripped ego instantly. As we couldn't get Zappa, Harper is a marvelous man and a crucial chum. Despite him being a sage, poet, and muse, that's not to say he didn't occasionally enjoy some of the Led Zeppelin by-products—like the occasional blowjob! No, no, not true! Alongside Richard Cole, they were quite a duo.

JIMMY PAGE Stormcock was a fabulous album [that] didn't sell anything. Also, they wouldn't release [Roy Harper's] albums in America for quite a long time. For that, I just thought, “Well, hats off to you.” Hats off to anybody who sticks by what they think is right and has the courage not to sell out. We did a whole set of country blues and traditional blues numbers that Robert suggested. But [“Hats Off to (Roy) Harper”] was the only one we put on the record.

ANDY JOHNS We finished Led Zeppelin III at Island and Olympic. At Olympic, we had this fabulous mixer and the gear really worked. It was somewhat intimidating because they would play so fucking loud. In a small space like that, the sound pressure builds up and stops other frequencies from happening.

DIGBY SMITH (tape operator on Island sessions for the third and fourth Zeppelin albums) Zeppelin used Island's Studio One at Basing Street extensively for III and IV. The room was massive, you could get a seventy-piece orchestra in there. The sound was cavernous and reverberant and live; it wasn't a tiny little den. The problem was controlling the live-ness of it, so the sound was heavily compressed by Andy. It seemed like whenever he was at the desk, everything got bigger and louder: the excitement levels rose. The quality of the sound he could create and the speed with which he worked really impressed me. The confidence he exuded fed through to the band. If George Martin was the fifth Beatle, then Andy was the fifth member of Zeppelin at that point.

ANDY JOHNS One night during the third album sessions, Coley was going out to get fish and chips, and Page said, “Can you get us some cocaine as well?” I went, “Excuse me. Cocaine? If you chaps bring cocaine into this, I will just go home.” This is 1970, and I'm twenty years old, and I thought cocaine was the drug of the devil.

GLYN JOHNS (engineer on first Zeppelin album) I love my brother to bits, and I think he's fucking brilliant at what he does: if you want to talk about heavy rock, I don't think there's anyone who beats him. But from a very early age he was influenced by those around him, and I was very naïve about it. So naïve, in fact, that I recommended him to the Rolling Stones, which was about the stupidest thing I could have done. Keith Richards got hold of him, and five minutes later he was a junkie.

JIMMY PAGE “Since I've Been Loving You” was already written, because there was a version of it at the Royal Albert Hall. The only unfortunate thing was that the keyboard wasn't recorded; otherwise it would have been really interesting.

DIGBY SMITH My recollection is that the vocal for “Since I've Been Loving You” was pretty much one take, and it was just electrifying. There are occasions as an engineer in the studio when it's your job to watch the levels for distortion and make sure the reverb's right and the equalizing is right, but you transcend into this other world where you actually forget you're recording, where you're actually present for a performance. And when I listen to that track, I'm taken right back there as if it was happening for the first time. I'm right there in the studio and I'm hearing every breath … and it's still magical.

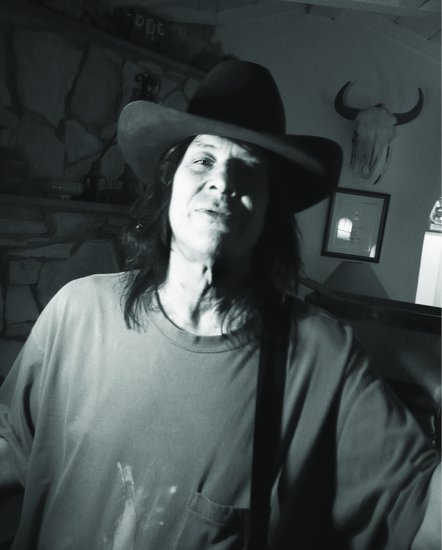

Andy Johns at home in Los Angeles, July 2010. (Art Sperl)

ROBERT PLANT The musical progression at the end of each verse is not a natural place to go. It makes it a bit more classy than a 12-bar, and it's that lift up there that's so regal and so emotional. I don't know who did it or how it was born, but I know that when we reached that point in each verse, musically and emotively, the projection of it gave it class and something to be proud of. You got a lump in your throat just from being in the middle of it.

TERRY MANNING They hadn't quite finished the third album, and they had an American tour booked. I had taken Jimmy to Ardent, so he already knew the studio, and he asked if I could help him finish the album there between shows. He and Peter would fly into Memphis, and anyone who was doing a part would fly in for a day or two.

What sticks in my mind is the strength of Jimmy's personality: the ability to discern what ought to be done out of the mélange of just things you could do. I would watch him listen to playback, and he had this little dance he would do where he'd shake his shoulders back and forth. And when that happened, I knew we were there.

Jimmy and I had a longer period where we mixed the album, and then I took it to a place called Mastercraft and physically mastered it onto vinyl. Jimmy was there, Robert was there, Peter was there, and a guy called Paul who had to be there because he had the keys. I was about to run “Since I've Been Loving You” down, and I went to the bathroom to give it what we used to call “the hall test,” where you hear it somewhat from afar, all mushed together into mono. And that kind of tells you what it's really going to be like. And I stopped in the hallway and thought, “Damn, that one's really good.” I remember thinking Janis Joplin a little bit in my head.

Right on the spur of the moment, Jimmy said, “I want to write some Crowley things in there.” He wanted to write “Do What Thou Wilt Shall Be the Whole of the Law” on one side, but it wouldn't fit, so we just wrote “Do What Thou Wilt.” On the other side, we wrote “So Mote Be It.” There were two pressings that were different. I said to Jimmy and Robert, “Someday people will have to buy two copies to get both versions!” We all thought that was very funny.

CHRIS WELCH I remember Jimmy showing me a book by Crowley. It wasn't as if it was some great crime. There were a lot of people getting into black magic, so it didn't seem unusual. I think Dennis Wheatley was as much to blame for that as anyone.

TERRY MANNING Jimmy and I talked about Crowley quite a bit. I knew of Crowley before, but Jimmy had really drawn him to the forefront and would talk incessantly about it. We even got into a couple of friendly philosophical arguments about it, because Jimmy was fully buying into the “Do What Thou Wilt” scenario. I said, “Okay, so if I wilt to kill you, shall I do that?” And he said, “No, that's not what it means.” I never got the impression from him that he was thinking anything satanic or evil; to me, it was all self-will and the ability to be totally free in the world and decide your own fate.

LORI MATTIX (groupie and Page's main L.A. squeeze circa 1973) Jimmy said it was all about the will—“I will have this”—and that's what Crowley believed. He said it was the white light that he liked, and when you want something, you will it. So that was Jimmy's philosophy: “I will have success, and I will have everything I want.” I think he willed so much success that that's what ate him alive: he got everything he wanted, and it got too decadent. You lose out on love. Every time he tried to find it, he was hurt again and again and disappointed.

MARTIN STONE (English guitarist and dealer in occult books) Black magic paraphernalia became almost obligatory for certain kinds of heavy metal groups, but Zeppelin were the only one where it carried any real weight, apart from a stylistic comic-strip superimposition.

JON WEALLEANS (architect who drew up plans for Page's occult bookshop the Equinox) My take on it at the time, and now, is that Jimmy was a collector anyway of slightly arcane things. Graham Bond had all this stuff of Aleister Crowley's, and Jimmy sort of bought a job lot of clocks and wands. They were props. I don't think Jimmy was seriously into black magic at all. Crowley was an interesting guy and a very bad poet.

PAMELA DES BARRES (groupie and Page's L.A. girlfriend in the late '60s) There was a bookstore that I frequented on Hollywood Boulevard, and Jimmy was always hunting for manuscripts, so I just wandered in there, and the guy had a manuscript by Crowley with all these handwritten notes in it. You can only imagine what it's worth now. I still have it in my diary—a telegraph with the money to buy it and send it to Jimmy, and that was such an honor. Look what I'm doing! He was exploring and trying to be expansive. He was very deeply spiritual. He wanted to be in control and in charge.

RICHARD COLE Right from before I even moved down to Pangbourne, Jimmy would ask me if I could take him somewhere to buy some Crowley artifacts or books or stuff. But no one ever really delved into what he did. When he bought Boleskine House, which had belonged to Crowley, he never gave any reasons. He didn't speak about it much. It really was a mystery to everyone else.

JIMMY PAGE [Boleskine House] was built on the site of a kirk dating from around the tenth century that had been burned down with all its congregation. Nobody wanted it, it was in such a state of decay … [it's] a perfect place to go when one starts getting wound up by the clock. I bought it to go up and write in.

MALCOLM DENT (caretaker at Boleskine House) Jimmy caught me at a time in my life when I wasn't doing a great deal and asked me to come up and run the place. I never did establish why he fixed on me. Initially, I thought I'd be coming for a year or so, but then it got its hooks in me. I met my then wife at Boleskine House. My children were raised there—my son Malcolm was born at Boleskine.

• • •

ROBERT PLANT To go from “Good Times, Bad Times,” “How Many More Times,” [and] “Communication Breakdown” to “Whole Lotta Love” and “Ramble On” and still only twenty-two, I thought was quite a move for a kid from the Black Country. And then to go from that to the third album—the cottage album—was incredibly important for my dignity. The acoustic stuff like “Friends” made Led Zeppelin much more powerful, not just a hit machine.

TERRY MANNING There's a thing in the music business known as the Third Album Syndrome, because that's where you either make it for a serious full career or you fall by the wayside. Jimmy was aware of that and wanted to be sure they didn't just repeat the role they had played before. He told me in advance, “You may be surprised, because this is different.” But in any case, I knew they liked folk music. There was an element that hadn't liked the first two albums. I had friends who said, “Ah, that stuff's just bashing, and the singer sounds like he's falling off a cliff.” Jimmy heard some of that, and he thought, “Okay, I'll show you.”

Zeppelin unplugged: Trentham Gardens, Stoke, March 14, 1971. (Rex Features)

HENRY SMITH The press wanted Zeppelin to be Zeppelin all the time. All they wanted was for them to come out and howl, and that's not what Zeppelin was about. People had to start realizing that Zeppelin was a continued story, and every chapter was different.

I loved the acoustic part of Zeppelin. I remember Jimmy just sitting around the house playing acoustic, and that was always a great spot to be in. It was a dream of Page's at the time to be like the medicine man in a little horse-drawn cart, going around England, selling potions, but he wanted to do that with a guitar. That was a country side of Jimmy that was almost like a Roy Harper. That was as much Pagey as “Whole Lotta Love” was.

JOHN MENDELSOHN (reviewer of first two Zeppelin albums for Rolling Stone) When Led Zeppelin III came out, there was actually a song on it that I really liked. I thought that I might be asked to review it, but Lester Bangs was given it instead, and he praised exactly the song I had liked—”That's the Way.” Lyrically, it was extremely bad, but I remember it feeling evocative, and it actually inspired one of my own songs.

JIMMY PAGE I think [Bonzo] originally had some lyrics about drinking pints of bitter, you know: “Now I'm feeling better because I'm out on the tiles … ” He used to do a lot of sort of rap stuff. He would just get drunk and start singing things like what you hear in the beginning of “The Ocean.” He would stomp his feet, and his fingers would get going.

CHRIS WELCH Bonzo would get nervous before shows. I remember walking up a ramp to a stage with him once, and he suddenly shouted, “Christians to the lions!” That's how they felt when they heard the baying of the crowd.

ANDY JOHNS To start with, Bonzo was manageable and seemed kind and all that, but the bigger they got, the worse he became. That had a lot to do with Pagey, because Pagey would wind him and Coley up and let them go. I saw things that I will not mention to you that were abominable. They loved to humiliate females. Jason used to say to me, “Tell me a great story about my dad.” I would say, “You don't want to know.” “No, tell me a great story.” “Your father was a lout and a fuckhead. I told you not to ask.”

ANNI IVIL (Atlantic Records press officer in the U.K.) At one Zeppelin gig, I saw Bonham starting to fall off his stool, and I went and held on and shrieked for somebody to come. I was just relieved he didn't fall on me.

HENRY SMITH Out of everyone in the band, he was the hardest one to keep under control. And it wasn't because he was disrespectful, it's just because he was out for fun. If there was ever any discord in the band, it was just that Bonzo was getting too drunk sometimes.

We did two shows in Cleveland, Ohio, and it was Bonzo's birthday. In between the shows, Peter said, “Go get some champagne, and we'll celebrate his birthday.” He might have given me a hundred-dollar bill, so I went to this liquor store and bought all the good champagne I could get for that money. Well, Bonzo got totally wasted, to where he really couldn't play. And when we got onstage for the second show, I was holding his seat and holding him up by the scruff of his collar, just so he could get through the set.

I think after that show it was like, “Bonzo, if you don't clean up, you're out of the band.”

DAVE PEGG Fairport Convention was in L.A. at the Troubadour club. We'd done one night there already, and on the second night Zeppelin were on at the Forum. They were all coming down to the Troubadour to see us. So for our second set, they all turn up after their gig, and it was, “We wanna have a play.” So I went, “That's fantastic.” So they all got up. Jonesy had my bass. Richard Thompson stayed onstage with them, and Simon Nicol gave Jimmy his Gibson. They did the whole of the second set, pretty much, and it was fantastic. We had to buy Mattacks a set of new heads for his kit because they were heavily indented by Bonzo's playing.

There was a new club opening the following day where Savoy Brown was due to play. Bonzo said, “We're all invited back there. We're going back for a game of pool and for drinks.” It was about two a.m. when we got there. It got to four o'clock, and the guy said, “Right, you're gonna have to go now, guys. It's going to be light soon.” Bonzo said, “I'll go if you beat me on the pool table.” So they had this game of pool, and Bonzo won. He beat the guy, and it got to five o'clock, and the same thing happened, and it's now six in the morning.

We're all very over-refreshed, to say the least, and all of a sudden there's the sound of the police. The room just clears, and Bonzo says, “Come with me!” So I follow him and go onto the stage, and we're hiding behind these 4-by-12 barstools, a big stack. I'm slumped behind one, and he's behind the other. I pass out, and the next thing I know, the sun is streaking through the window. It's nine a.m., the place is deserted, and Bonzo is passed out next to me. I go, “Shit! What happened? Where the fuck are we?” He goes, “Oh, it'll be alright. My driver will be outside.” There's nobody in the club, so we creep out of the club, and outside there's a big limo. The guy's been waiting all night.

The driver drops me off at the Tropicana motel, and Bonzo says, “I'm off to Hawaii tonight. We're playing in Honolulu tomorrow.” I get back to the Tropicana, and at one o'clock the phone goes, and it's Bonzo: “Fancy a drink before I go?” I say, “Oh, alright.” So he comes round, and we go to Barney's Beanery just up the road. We have a few beers, and Janis Joplin comes in and sits down next to us. It was unbelievable. At five p.m., I'm going, “You should have gone.” Bonzo says, “Ah, fuck it. I can get a later flight, whatever.” I say, “You really should go.” “Fuck it. Fuck 'em.” He really didn't give a shit.

At six-thirty, his flight's gone anyway, and I'm completely blotto. Anthea Joseph, our tour manager, comes to collect us. She's in the middle of us two lumps, and she's walking us three hundred yards back to the Tropicana. We get to the Tropicana, and up the steps there's a swimming pool where Andy Warhol and some other people are sitting round the side of the pool. I've got to go in an hour and a half to do the first set that's being recorded, and Bonzo pushes me into the pool, fully dressed. I think, “I'll get you, you bastard,” so I push him in the pool, and then he gets out and takes all his clothes off, except for his Y fronts, and he's having a swim, and he's left his clothes by the side of the pool. He comes out, and we're befriended by two Texan girls with a big bag of grass, which we take back to our room and carry on partying for a bit. Then I have to go to the Troubadour to do the first set. I'm drinking black coffee, cold water, in a fucking dreadful state.

Just before the second set starts, there's a phone call from Bonzo, going, “Where am I? Can you help us out?” He was in my room at the Tropicana, and he'd gone out to the pool in his wet Y fronts, and all his clothes had been nicked. So he borrowed some of the clothes out of my suitcase and came down to the club, and we had to loan him the dosh to get the ticket to get to Honolulu. I thought, “Peter Grant's going to fucking murder us.” Bonzo made it to Hawaii. Don't ask me how.

BILL HARRY We used to set up interviews in the Coach and Horses in Soho. I'd be interviewing somebody, and I'd see Bonzo in the bar, and he used to be with people like Stan Webb of Chicken Shack. They'd get a glass and put Cointreau in, put vodka in, put this in. There was one time when they were doing that, and I knew they were up to mischief, and I thought, “Bloody hell, something's going to happen here.” So I rushed back into the office because I had Glenn Cornick of Jethro Tull doing an interview there. I locked him in my office, and I heard them coming up the stairs. I rushed into Terry Ellis's and Chris Wright's office, and it was empty, and I shoved the door shut.

Suddenly, I heard a big bang, and they knocked the door off the hinges and grabbed hold of Doug D'Arcy and got all this tape and completely wrapped him up and dumped him in Oxford Street. For some reason, they then came after me and dangled me out of the window. They then went to Morris Berman's and rented out these Arab costumes. They went back to the Maharishi Suite at the Mayfair Hotel. They told me that later that night, when I was in the Speakeasy, there were two blue-rinsed ladies in the lift with them, and they turned around and lifted up their things, and they had nothing on underneath, so the women beat them with their umbrellas.

Bonzo ordered steaks for fifty people, and all the waiters came in with all the trolleys, and after the waiters had gone, they threw the steaks all around the room. That got Bonzo banned from every hotel in London.

GLENN HUGHES (singer and bassist with Trapeze and Deep Purple) I could give you a hundred stories about Boisterous John that you've probably already heard. The guy I knew was a family man who missed his wife when he was on the road and who loved his fucking music. He didn't know he was an alcoholic, he just wanted to emulate Keith Moon—he definitely wanted to be in the Oliver Reed club. I remember going to the Elbow Room in Birmingham one late night with John, and he probably bought twenty pints of beer and lined them up on the bar. He was a very generous man, let's be clear about that. He would literally give you the shirt off his back. But if you took a sip of his beer, he would go fucking mad.

ROSS HALFIN (photographer and friend of Page's) John was Tony Iommi's best man, and they were out all night drinking and doing a load of coke—“on the waffle dust,” as Tony puts it—and at one in the morning Bonzo orders thirteen bottles of champagne. Eventually, they end up back at Bonham's, and Pat opens the door and says to Iommi, “Fuck off, the pair of you!” Tony goes, “Pat, please, I'm getting married in the morning.” Pat says, “Alright, but fucking leave him there.” And they just leave Bonzo lying on the floor in the front hall.

Eight a.m., there's a knock at Tony's door, and Bonzo's standing there all dressed in his suit, kipper tie and all, waiting to take Tony to the church.