17

Almost Infamous

The trouble is now, with rock 'n' roll and stuff, it gets so big that it loses what once upon a time was a magnificent thing, where it was special and quite elusive and occasionally a little sinister, and it had its own world and nobody could get in.

—Robert Plant, May 2008

DAVE NORTHOVER (John Paul Jones's assistant on Zeppelin's 1975 and 1977 U.S. tours) I used to play rugby in Hellingly, and Peter Grant would come to the White Hart in Horsebridge with his wife to enjoy the mayhem we created when we got off the pitch. They seemed very happy together. Gloria wasn't a typical rock wife at all; I don't think she even indulged in any chemicals. She was very concerned with her kids.

HELEN GRANT (daughter of Peter Grant) I didn't really like a lot of people knowing about Dad. I kept it relatively quiet at school. And then there was a big article in the Sunday Times, and everyone got to know about it. I used to say, “For God's sake, turn up in something understated.” All the other parents were turning up in Volvos, and Dad used to come screaming round the corner at boarding school in a Bentley and goggles and scarf.

DAVE NORTHOVER Just before Christmas of 1974, Peter invited me round and asked if I'd like to come on tour. I had once been a physicist, and when Peter told the rest of the guys he was taking me on the tour, they thought he said pharmacist. Jimmy's ears pricked up, and he said, “Bring him along!”

JACK CALMES (cofounder of Showco sound and lighting company) For the 1975 tour, we went up to a much higher level of production. It went to six or seven trucks and a whole bunch of stuff and a stage. I went over to the New King's Road, and they got me up in the little meeting room above the ground floor. Peter Grant started the meeting and said, “Alright, what have you got for us?” I kind of choked because it was a big number. He said, “Well, let's have a blow first.” So he pulled out a big Bowie knife—about a foot long with a three-inch blade on it—and dipped it into this kind of grocery sack of blow. He said, “Here, Calmes, have some.” They had to give me five minutes to recover from that.

So they were all sitting there staring at me, which was pretty intense. We unveiled the model and showed it to them. Bonham looked at me and said, “How much fucking money is this going to cost us?” I said, “$15,785 per show.” The room went dead silent. Not a word. They started looking at each other sideways. Bonzo got up, walked over to the window on the New Kings Road, and opened it up like he was going to throw me out of it. Then he came over to me, gave me a huge bear hug, and started laughing. He said, “Yeah, go for it. We're in.”

DAVE NORTHOVER The first date was in Chicago. It was the 17th of January 1975, it was 17 below, and there were seventeen thousand people at the concert. I had no idea just how huge Zeppelin were until I was standing at the side of the stage with all these kids screaming and jumping up and down.

ROBERT PLANT There was a minute there when I thought we'd lost it after that first show. The whole idea of Zeppelin has always been getting each other off—and that was missing until the second night. Then it suddenly came together—we looked at each other and we all knew it—we were there again. The magic had returned.

DANNY MARKUS (artist relations in Atlantic's Midwest office) In Chicago, they would stay at the Ambassador, which is two hotels, and there was an underground tunnel between the two. At five o'clock, we would meet in the lobby, climb into the limousines, and go to the airport to fly to Minneapolis or wherever it was. In Minneapolis, the airport was right next to the stadium, and we would go in, play the show, no encore, go off, and on the two-way radios I could still hear the audience calling for an encore as I was being served lobster thermidor on the plane. Hell, you didn't even need cocaine.

TONY MANDICH (artist relations in Atlantic's L.A. office) Everybody always wants to know what it was like being backstage at a Zeppelin concert. The truth is, there was nobody there. It was a ghost town. If they had a great show, the band would meet and greet certain people and all that, but if they had a bad show, they would jump in a limo right after with a police escort. The people were still screaming and yelling for them, and they were already gone.

DANNY MARKUS The band got along very well. Not like the Who, who were the most impossible thing I've ever seen and where everyone had a submanager. When they did the little acoustical set, Janine Safer and Neal Preston and I would go down in front of the barricade, and Neal would shoot pictures, and they would perform it for us. That would be the one point during the show where the three of us would meet, and we would try to make them laugh just to get the vibe going.

JIMMY PAGE The intention was to cut back in the January–February tour of America. “What are we doing? We're mad, three hours.” So we attempted to cut it back to two hours, and I don't know, it just went to three hours again.

DANNY GOLDBERG (president of Swan Song U.S. office) One night in Cleveland, Jimmy warned Robert that he was tired and to expect short solos. Then he went out and did more than eight minutes in “Over the Hills and Far Away.” Afterward, Robert said, “Short solos, huh?” Jimmy just grinned and shrugged.

BENJI LeFEVRE (Zeppelin sound technician, 1973–1980) Zeppelin treated the crew like shit, hardly paid anybody anything. There was this enormous thing between G and Jimmy, which was, “How can we squeeze the last penny out of everybody?”

On the 1973 tour, they gave us an old double-decker Greyhound bus with sleeping bags in the back. In 1975, they wouldn't even give us a sleeper coach: we had a Continental Trailways bus and had to do overnighters just sitting in seats. I wrote a letter to G, in which I complained bitterly about the way we were all treated. I said, “This is not right.”

Having grown up in the theater environment, I didn't get fazed by speaking my mind. People called me the trade unionist, but it was only because I had the balls to say something. Other people would be just like, “Yes sir, no sir.” It wasn't even so much the money as just “Cut us some slack and give us some respect.”

SALLY WILLIAMS (girlfriend of Bonham roadie Mick Hinton) Peter and Richard gave off this kind of Mafia vibe, this control over the band. I'd say to Mick [Hinton], “Well, surely you've been paid your bonus.” And he would say, “Nah, Richard hasn't paid us yet.” But then Richard will remind me that Mick would spend his bonus the moment he got it—usually on cocaine.

BENJI LeFEVRE With the Clockwork Orange boiler suits, Bonzo instructed Mick that this was how he would appear on the tour. Most people were completely shit-scared of both of them. Mick's main role was to set up the drums, but there were many times when Bonzo would just say, “Hinton, you're coming with me now!”

GLENN HUGHES (bassist and singer with Deep Purple, 1973–1976) I was in New York and really fucked up. I'd had an ounce of coke flown in from L.A., and I'd been partying pretty strong with Mick Jagger at the Plaza. I was getting a bit too high, and I wanted to get out of there, like, “I'm a little too high for these dudes …”

“Mr. Ultraviolence” and his demonic twin: Bonzo and Clockwork Orange dogsbody Mick Hinton on the '75 tour. (Neal Preston/Corbis)

Later I call Jagger, and I think I'm speaking to him, but it's Hinton I'm on the phone to. They'd put me through to his room by mistake. I invite him to come over, thinking Jagger is coming round. And lo and behold, there's a knock at the door, and it's Hinton. I'm completely off my tree, I'm shaking, I'm twitching, I'm sweating, I'm wearing a kimono, completely paranoid: the last thing I want to see is Bonzo's evil-twin Clockwork Orange brother, frothing at the mouth.

Mick goes, “I know what to do with you, fucking Hughesy!” And he pulls out a fucking syringe and says, “I'll fuckin' stab you with this.” Obviously, it was heroin or something, so I was convinced I was going to die. Fortunately, there was a guy in the room who got him out of there. Hinton scared the shit out of me. He was Bonzo's Man Friday. Jason Bonham and I have laughed our asses off with the Bonzo and Hinton stories. Mick would have done anything for John.

JACK CALMES Jimmy got sick in Chicago, and I mean rockin' pneumonia sick. I was there, and I came to get paid. Peter says, “You fucking greedy cunt. You're here collecting money when Jimmy's sick!” I said, “Yeah, actually I am. We've got people to pay.”

Peter threw a big fit. They'd started the show and gone onstage. They'd thrown a trash can over one of the monitor guys onstage and were just being bastards. So I told Peter, “We're done. We quit. We're not going to be treated like this. We're out of here. I'll give you two days to get somebody else, but we're not doing this. Good-bye.”

About four hours later, I get a call from Steve Weiss and Peter, and they say, “You need to come over to the Whitehall Hotel and have a meeting about this.” I get to the room, and Steve Weiss is on the phone, putting out a contract on my life. I'm listening to this third-hand thing that Steve is saying: “Bad things will happen to Calmes. We know where he lives.” I'm about to shit my pants when I notice Peter looking at me with a twinkle in his eye. I went, “Oh fuck.”

CHRIS CHARLESWORTH (New York correspondent for Melody Maker) I was always a bit wary around Led Zeppelin because—Plant aside—there wasn't a very friendly atmosphere coming from them. They were a bit touchy. Every other word with Peter was “fucking” or “cunt.”

ROY CARR (writer for New Musical Express) Bad Company were playing Madison Square Garden, and Peter rang me and said, “Do you wanna come over for a few days?” I went over, and he said, “You know, I know people think I'm an evil bastard, but you know and I know that there are so many crooks in the States that just want to latch on. I just want to keep them away from the bands.” He said he'd been approached by the Mafia. That was going on, with Zeppelin being so big.

NICK KENT (writer for New Musical Express) Grant was the closest thing to a Tony Soprano that I've ever known, because you wanted to like the guy and because he knew the difference between right and wrong. But what he'd come up with through his life meant that he couldn't trust people.

BENJI LeFEVRE Peter liked villains because he was a fucking villain. He liked getting physical with people. On the New King's Road, we had Krays people hanging round all the time. Poor Carol Browne used to sit there wincing.

BEBE BUELL (groupie and girlfriend of Page's) Being with Zeppelin was like being Ava Gardner with Frank Sinatra. You had to be part of the entourage in order to do certain things. If you weren't, you were kept at bay. After I went to see a Bad Company show, rumors even started flying around that I was dating Peter. But he never even tried to hold my hand. Most of the time I would sit in his room, crying my eyes out about Jimmy. And I'm sure he'd already had to console many a damsel.

ROBERT PLANT We had twitchy times at the end, me and Peter, but I owe so much of my confidence and my pigheadedness to him because of the way he calmed and nurtured and pushed and cajoled all of us to make us what we were.

PETER GRANT By that time, the security thing in the U.S. was getting ridiculous. We started getting death threats; in fact, straight after the '73 tour following the Drake robbery, there was a very serious one. Some crackpot letter from Jamaica stating what was in store for us when we toured again.

It got very worrying. That's how we lost a little of the camaraderie after that when we were in America, because there were armed guards outside the hotel rooms all the time. I think we even talked about wearing bulletproof vests at one time.

PHIL CARLO (roadie for Bad Company) We actually had CIA and FBI men and a marshal called Bill Charlton, who could move people from state to state and arrest people. All these people were provided by an ex-cop called Steve Rosenberg, who was Steve Weiss's mate. We had this Boston detective on the Bad Company tour who'd go and bust people if the band ran short of dope. He'd take the dope off them and tell them to fuck off and not do it again, and then he'd bring back the dope to the hotel and hand it over to us.

DANNY MARKUS Ahmet saw Peter as some kind of British version of Colonel Tom Parker. He appreciated the way he operated, even in a primitive sense.

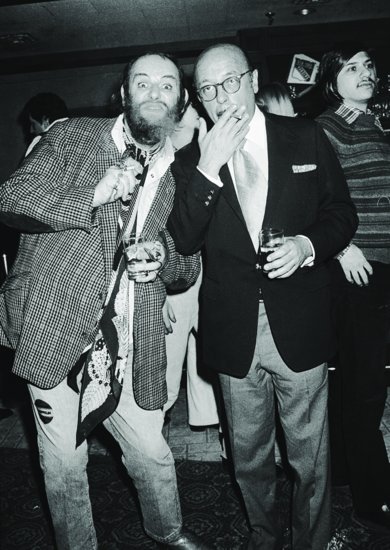

Grant with Ahmet on the 1975 tour. (Neal Preston/Corbis)

ELIZABETH IaNNACI (artist relations in Atlantic's L.A. office) Ahmet was a lover of the message and not the messenger. This man loved music so much that I don't think he put judgment on what the bands did. He didn't behave badly himself and consequently did not judge those who did. He might have agreed with Dylan Thomas, who said that to create was to always be living on the edge of madness.

DANNY MARKUS Partly because I never did drugs, I wasn't so scared of Peter. I could go in the cage. I'd have Peter doing tricks—not for me, but there were channels open. And Ricardo was always very kind to me. His job was to create tension, and mine was to ease it. There was always tension backstage, and Richard played it like a piano. You had no fear inside, but it created an outside thing that was just incredible. Peter kept a very high intensity of social order, and it was very hard to get inside.

MARILYN COLE (wife of Richard Cole) Peter was warm, funny, powerful, terrifying. He wasn't an éminence grise, but there was an aura of ultimate power about him. Zeppelin dealt in intimidation; that's how they got their way. If you knew Richard, really, he was a pussycat. His true nature was far gentler than his aura as part of Zeppelin.

GLENN HUGHES Cole was the scariest man I ever met in my life. I witnessed his behavior in person, saw him in full fucking flight. When he said, “I'll fuckin' 'ave you!” it was like, “I could kill you and nobody would know about it.”

JANINE SAFER (press officer, Swan Song in the U.S.) Was Richard raised by really mean wolves? It's like the Eddie Izzard sketch. It didn't matter if he was buying toothpaste at the drugstore, the subtext was always “Fuck you.” The glass wasn't even half-empty, it was totally empty. But the thought of firing him and hiring someone they didn't know was unthinkable and impossible.

MARILYN COLE We got married at the Playboy Club, and Peter paid for everything. Lionel Bart was at the piano. I remember my mum saying, “Why is there such a long queue for the toilet, and why are they all coming out with white powder on their noses?” Bless her.

After the wedding, I thought, “That was great. Now what do I do?” I asked Richard how much he earned. And when he told me, I said, “What? That'll do for me, Rich. What are you gonna live on?” They were the stingiest lot you've ever met. Richard adored Peter. Peter was his father, his god, his mentor. And then along comes me.

JACK CALMES I don't think the Zeppelin people thought Richard was ever going to be employed by anyone else, but I got him the job as tour manager on Eric Clapton's 461 Ocean Boulevard tour.

MARILYN COLE Robert Stigwood offers Richard three times what he earned in a year with Zeppelin to take Eric out of hibernation for a couple of months. Rich says to me, “Oh, but I couldn't leave the boys.” I say to him, “You fucking what? You turn this down and it's good-bye.” Dear Richard, he had no self-esteem whatsoever. He'd been mollycoddled by Big Daddy G. Of course, they were gobsmacked.

RICHARD COLE It was a hell of a lot more than Zeppelin were paying me, more than likely ten times as much—something like $16,000 for eight weeks' work. I spoke to Ahmet, and he said, “You should do this.” Before I took it on, I called Peter and said, “Are you gonna give me a piece of Swan Song for all the fucking work I've done?” He said no, so I said, “Right then, I'm off in the morning.”

JACK CALMES Richard was still doing a lot of drugs, and Clapton was trying to dry out, so Richard was walking a fine line there. His methodology of dealing with everything was the slash-and-burn mentality of Led Zeppelin, whereas the Clapton tour was kind of frail because he was coming back. But he did a good job and was enough of a pro to pull it off.

RICHARD COLE Ahmet was a crafty old fucker, believe me. I was out on the piss in New Orleans with him and Eric and Marilyn and Earl McGrath, and he said, “You know Zeppelin are back on the road next year?” I said I had heard. He said, “You'll be doing it.” I said, “Nah, fuck 'em.” He said, “You've got to do it. Who else is going to do it?” I don't know if he spoke to Peter, but Jimmy and Robert then came down to see me in Pangbourne.

MARILYN COLE Jimmy, Robert, and Peter came to our barn—where they'd never been before—and Richard, of course, behaved like the Queen had arrived. I'd cooked this casserole in Guinness or something, which somehow fed everyone. Peter comes out with “I see we're gonna 'ave to deal with Leni.” I said, “Who, Riefenstahl? She was great, wasn't she?” In the end, they quadrupled his salary, gave him a Jaguar and a much bigger expense account. But he's grossly undervalued by them to this day.

CHRIS CHARLESWORTH The undercurrent of unpleasantness was so unnecessary. They were the biggest band in the world. They could outdraw the Stones and the Who. They could do as many gigs as they wanted in the biggest arenas, and no one was going to attack them.

The latent violence wasn't there with any other bands of that stature—and certainly not the Who, a band that I spent a lot of time with. There might have been a row in the dressing room after a bad Who gig, but there was nothing like the bad vibes and that hint of menace around Zeppelin. They behaved as if they were a law unto themselves. They could protect themselves with this crew of gangsters, and they could do pretty much what they liked … short of murder.

BENJI LeFEVRE If there was something distasteful going on, you tended to have another drink or another joint and go, “Ah, it'll be alright, fuck it. At least, no one's got killed … yet.” When you're twenty-something and involved in something that enormous, it doesn't matter. You just go along for the ride.

DANNY GOLDBERG I didn't see anybody beaten up, but I saw people threatened. I was nervous. I didn't want anybody mad at me. There's no question that you didn't cross Richard Cole, but the person who was the most prone to violence was Bonham when he got drunk. He'd push people around, and then it would be Richard's job to try and restrain him.

NICK KENT Taking cocaine just enabled Bonham to drink more. The combination of cocaine and alcohol is almost as dangerous as heroin, because you end up with two separate addictions. Plus, people were worried about him getting into heroin. It was like, “Whatever you do, don't let him do smack. He'll snort the whole gram and overdose.”

JOE JAMMER (blues guitarist and former Zeppelin roadie) Page being a student of Aleister Crowley, they didn't call Bonham “The Beast” lightly. Something made him unhappy as time went on, because he became more and more violent.

JOHN BONHAM (speaking in 1975) I've got worse—terribly bad nerves all the time. Once we start into “Rock and Roll,” I'm fine. I just can't stand sitting around, and I worry about playing badly. Everybody in the band is the same, and each has some little thing they do before we go on, just like pacing about or lighting a cigarette. It used to be worse at festivals. You might have to sit around for a whole day, and you daren't drink, because you'll get tired out and blow it. So you sit drinking tea in a caravan with everybody saying, “Far out, man.”

DAVE NORTHOVER When we were leaving the gigs in the limos, although everyone was exhausted, Bonzo would be very hyped up. There was no way he would be quietly going to bed. He never wanted to go to bed before it got light.

JOHN PAUL JONES Bonzo drank for reasons. He hated being away from home. He really did, and between gigs he found it hard to cope. And he was terrified of flying: sometimes he'd drink too much and get the driver to turn around before he got to the airport. So things like that really don't help.

JANINE SAFER Personally, I was never in fear of Bonzo. I thought he was really a doll, one of the sweetest people. Miserably unhappy whenever Pat wasn't with him. Not very bright and not intellectually inclined. Of the four of them, he had the weakest hind legs. He liked playing the drums, and he loved his wife. He would be completely unhinged when she wasn't around.

MARILYN COLE The groupies troubled Bonzo. He called them “those old slags.” He couldn't come to terms with it. He'd be angry at them for what they were.

CHRIS CHARLESWORTH I was on the plane with them, and Bonham had passed out drunk. When he came round, he tried to attack the stewardess—literally tried to mount her from the rear. Everyone had been having a really nice time until then. Jones was playing the organ and everybody was singing along and getting pleasantly pissed, and suddenly the whole mood was broken by Bonham's arrival and his futile attempt to seduce the stewardess. The others manhandled him off her and frog-marched him back to the cabin where the bed was.

JANINE SAFER Danny Markus was in Artist Relations, a job that no longer exists in record companies and that basically entailed procuring drugs and women for bands. What a great job! Danny was smart, Danny was funny, and Danny had monogrammed rolling papers.

DANNY MARKUS Bonzo had a way of testing you. He used to squeeze your nipple until it was purple. There was a famous European publisher named Larry who had these amazing goggle glasses, and I found a guy in Chicago who made me a similar pair. So I had just gotten these glasses when I got on the Starship, and Bonzo comes up to me, takes the glasses off, throws them on the floor, and stomps on them.

About two nights later, I'm back on the Starship, and I'm wearing a new pair that I've had made up because the guy still had the prescription. I see Bonzo coming toward me, so I take the glasses off and I stomp on them. I never had a problem with Bonzo ever again after that. He just wanted to see that you weren't afraid of him—to see whether you could take a punch. I mean, don't get me wrong, he was an ugly drunk. If you were on the inside, you were okay, but if you were on the outside, it was like he was swinging a ropeful of razorblades and slicing anybody in his path.

NICK KENT I've never seen anyone behave worse in my life than Bonham and Cole. I once saw them beat a guy senseless for no reason and then drop money on his face. It makes me sick when I hear Plant talking about what a great geezer Bonzo was, because the guy was a schizophrenic animal, like something out of Straw Dogs.

DAVE NORTHOVER I had the suite below John's at the Hyatt House. There's a knock at the door, and here's Keith Moon: “David, I've tried to get into John's room, and he won't let me in.” I said, “What do you want me to do about it?” He said, “I've got an idea. I could climb up the outside.” Bear in mind, we're on the eighth floor of the hotel. So we go out on the balcony, with the balustrade for John's room about seven or eight feet above us. Keith said, “All you've got to do is just give me a lift up. I'll be fine.”

Keith gets up on the balcony, and I've got his ankles. He says, “Right. Lift!” And I'm thinking, “If I let go, it's going to be worldwide news, and I'm going to be dead.” But he made it, pulled himself over the balcony, and barged into John's suite. John freaked, rushed into the bathroom and flushed everything down the loo. Next thing I know, I get a phone call asking me to “arrange further supplies.”

For some reason, John had a small upright piano in the room, and things got fairly excitable. The music was going, and the piano was going. I was thinking, “I'm going to go out in a minute because they're being noisy bastards.” And then I heard a bang, a rumble, another bang, another rumble … and then a huge crash. They'd tipped the piano over the edge of the balcony. It missed a limo by about ten feet.

GLENN HUGHES I remember we were having a bit of a party at the Rainbow with Robert Palmer. John takes an eight ball of coke out of his pocket and throws it into his cupped hands and cups the whole eight ball up into his face … and we're catching the crumbs as they fall down. I mean, you've heard of excess, and this is one of those moments where you can't believe what you're seeing.

BENJI LeFEVRE I have never seen so much cocaine. It was fucking insane. Whenever you get into that journey, it's never quite enough, and you always want just a little bit more.

NICK KENT You had countless cocaine dealers in Hollywood, and they would give coke to bands for free because they wanted to be able to say, “Did ya see Zeppelin at the Forum last week? Well, they were high on my cocaine.”

DESIREE KIRKE (wife of Bad Company's Simon Kirke) We partied hard. Too young to live, too fast to die. But reality always seeps in. It took me years to get sober, till the mid-'90s.

GLENN HUGHES We all know that there was white powder going around other than coke.

BENJI LeFEVRE Sometimes the “subtle blend”—as Jimmy used to call it—didn't quite work, so he'd try a little bit more of the one and a little bit less of the other. It all just escalated into complete mayhem; 1973 was, without a doubt, the most fantastic fun. On the '75 tour, on the other hand, there were certainly occasions where Jimmy was too fucked up to play.

PETER GRANT I remember the first time Jerry Weintraub saw Jimmy on a tour. He says to me, “Is that guy gonna live?”

PETER CLIFTON (director of The Song Remains the Same) Peter just loved Jimmy, and he was incredibly gentle with him. And Jimmy was incredibly rude, backed up by Peter. I remember at one early meeting, Peter just jumped up and ran out of the room—I didn't know he could move so fast! I said to Carol Browne, “What happened?” She said, “Jimmy just caught his finger in a door.” It was like a football manager and his favorite player. Jimmy was this fragile genius. He had a sort of incandescent beauty about him and a sense of helplessness.

GLORIA GRANT (wife of Peter Grant) Peter didn't want the good thing to fall apart. He didn't want to think it was all going to fold up or that he'd messed up. And that's why he helped Jimmy out in lots of ways—with his addiction and things. Peter nannied him. In some ways, Jimmy was like the little brother he'd never had.

I remember walking back from Hellingly School with Warren one afternoon, and Peter drew up in his Porsche and asked if I wanted a lift. I said no, because he'd been out all night. He told me later that Jimmy had OD'd, and he'd been trying to keep it all together.

NICK KENT At one point, Grant took me under his wing. He'd always say, “You're an ally.” So I flew with him to a Zeppelin gig, and after the show he said, “Come up to my room.” I'd taken a lot of cocaine, as had everybody, and he gave me a Valium to calm me down. But he also gave me a little talk about heroin, because I was already on that road—and he probably realized Page was on that road, too.

He sat down and really opened up to me, and at one point he pulled out this Karen Dalton album, In My Own Time, and said, “This is the greatest record ever made, and I wanted to manage her. So I went out and found her, and she was a junkie.”

GLENN HUGHES At the Hyatt House, you never saw the four of them together. Jonesy was never there, and Robert was sort of in and out. There were all kinds of debauchery going on. People would pop in and out, get a bird, disappear. Smoke-filled fucking rooms of opium and shit happening. It was kind of unsettling to me. I never felt comfortable in that scenario. I was never a big fan of the groupie thing.

BEBE BUELL I never got to know Robert well, but I always found him really sweet, really peace-and-love. He would shack up with one girl that would be his favorite, and you would never see much of him. He tried to re-create a family everywhere he went.

MIKE APPLETON (producer of the BBC2 show The Old Grey Whistle Test) I always equate Robert to some extent with Jagger, in that they were both in control of themselves. Robert and I could talk about almost anything. I remember being at the Hyatt House with him, and the only thing he was interested in at that particular moment was how Wolves had done that weekend. He had the papers flown out to him so he could read the match reports.

MARILYN COLE Robert, Bonzo, and Jonesy came into this nucleus of dark energy: the triangle of Jimmy, Peter, and Richard. And those three would always be ribbing “Percy” behind his back. Maybe they were just fucking jealous, but he was the scapegoat, the front man with the golden hair and the little blouses.

Robert didn't seem to give a fuck about the favoritism. Maybe he was more sure of himself, and had enough largesse to deal with it. He wasn't involved in that nucleus of mystery and magick. He wasn't sitting there with mounds of cocaine. He went home, whereas Peter and Jimmy were much more involved with each other.

MICHAEL DES BARRES (singer with Swan Song band Detective) Robert has white wings that flew him above the fray. He flew above it and smiled and laughed. He didn't need a driver, he didn't need a retinue. The difference between him and Jimmy was that he could step outside the whole thing and observe it. He had a mystical view of things.

MICK FARREN (writer for NME) The normal dynamic of a rock 'n' roll band is like Gene Vincent and the Blue Cats; it's the singer and his backing band. But where you've got a singer who is maybe not actually the top cat in the band, things get decidedly harder and have to be worked out.

DANNY GOLDBERG I watched [the relationship] change. Earlier, Jimmy really dominated the relationship completely. And he was the founder of the group, the producer of the records, wrote the music, and was just the psychic center of the group. And basically somewhat dominated Robert. Although Robert had his own life and his own thing, Jimmy was the stronger of the two in that relationship. At times when they would disagree, if Jimmy was vehement about something, Robert would go along with that.

But as time went by and Robert got older, he became more and more independent, to the point where, now, Robert is the stronger. He's certainly the more successful. But I would say by the end of Zeppelin, Robert had got the confidence to assert himself as an absolute equal.

NICK KENT Plant is one of those guys who wants to run his own game. The thing about him is that very, very quickly in America he became a sex symbol, and it was made very obvious to everyone involved in Led Zeppelin that he was as much a powerful image and force as Page was.

When I was with them in 1975, there was one thing that showed me what the Page-Plant dynamic was all about. Circus put out a book about Plant, and the guy who'd put it together came to a gig. After the gig, Page said he wanted to talk to this guy and wanted me to come along. So we got in one of the limos together, and Page really went for this guy. Like, “Why have you done a book just about Robert?”

I mean, Page was the leader of Led Zeppelin, you have to realize that. But when Plant became as popular as he did—when he became the Viking prince of rock—all of a sudden Jimmy couldn't tell him what to do anymore. He couldn't pull the whole “I was in the Yardbirds when you were still mending roads in West Bromwich.” Plant recognized it, and suddenly people had to treat him differently. Peter Grant could no longer tell Plant what to do: if Plant didn't like something, he was now going to say something about it. And if it got any worse, he might even walk out.

CHRIS CHARLESWORTH John Paul was a mystery. He showed no interest whatever in having any kind of profile. No one seemed to interview him very much, and he wouldn't be out in bars with the rest of them. He was nice enough, but he just wasn't there.

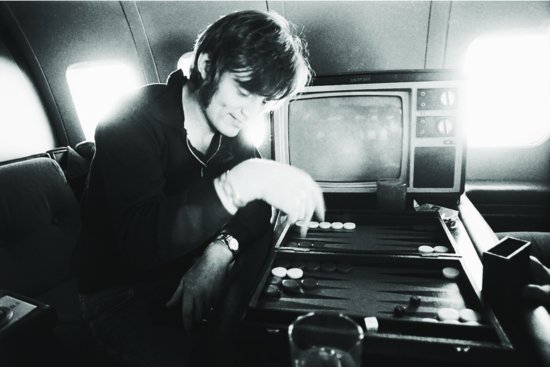

JANINE SAFER John Paul was incredibly bright, always the most grown-up and detached of them. He taught me how to play backgammon, which we would do for hours on the Starship. He was the consummate session musician, and in many ways Led Zeppelin was just another gig to him—albeit one that lasted many years.

Jonesy playing backgammon on the Starship, 1975. (Neal Preston/Corbis)

MARILYN COLE Jonesy never really looked like he belonged in Led Zeppelin. He was like a classical musician surrounded by rock stars.

JANINE SAFER Musically, John Paul would butt heads with Jimmy; he was the only one in the band who would do that. He would say, “No, that doesn't sound good,” and the two of them would at least discuss it. Jimmy was not imperious with him, which he was with almost everyone else.

DAVE NORTHOVER John Paul wasn't exactly aloof, but he didn't partake in all the silliness that went on. He tended to go off on his own, without any of the minders looking after him. That used to worry Peter a bit.

SAM AIZER (artist relations in the Swan Song U.S. office) John Paul and Brian Gallivan would come up to my little office, and I'd say, “What are you doing today?” Jonesy would say, “We're going to go see a movie.” Brian and him, that's what they did. They realized they could get away with it, and they liked getting away with it. Jimmy? Never. Everything that guy did had to be a drama.

DAVE NORTHOVER After one show, this chap invited John Paul out to his house, so we were driven out to see him. Just before we left, the guy said, “I'd really like to ball you both.” At which point John Paul said, “Well, David, I think it's probably time we left, don't you?”

• • •

JANE AYER (press officer in Atlantic's L.A. office) The year 1975 was huge for Zeppelin. That was the golden era of rock 'n' roll, and they were the biggest group in the world. For us, this was the Renaissance, and I just happened to be there at that peak time. Maybe I was like Cameron Crowe and an innocent, but on the West Coast—where I was doing press—I really did feel like the Harvey Kuberniks and David Rensins and Todd Everetts were receptive to Zeppelin. Danny Goldberg did an extraordinary job for the band, and I thought the relationship with American journalists at that point was very good.

HARVEY KUBERNIK (West Coast correspondent for Melody Maker) I went up to John Paul Jones at a Swan Song party and said, “I know this is Zeppelin and you're debuting your label, but I just have to tell you how much I love the Lulu and Donovan stuff you arranged.” He said, “I haven't been asked about them in a while.”

JAAN UHELSZKI (writer for Creem) I went to a couple of the gigs with them. I was there as a journalist, but I was also just kind of observing and taking it all in. I really was a little daunted. Richard Cole was more like a big loutish goof, but Peter Grant did scare the shit out of me. You didn't want to look at him the wrong way.

To me, that tour was the apex. Everything that they were and everything they had become and how far out they were taking it … those shows to me were mind-altering. People used to say that Pink Floyd took you on some kind of acid trip, whereas Zeppelin was much more physical—hence Physical Graffiti, I think. It was the difference between a chemical reaction and a physical reaction. You weren't altered, but you were agitated and tumbled around, and then it was over. Like sex.

DANNY GOLDBERG In 1973, the band had got a lot of attention for the sheer magnitude of what they were doing, playing these stadium shows. Rolling Stone wanted to do something on them, and the band said, “Fuck them. No.” So then, in 1975, Jann Wenner called me and said, “Okay, you can pick the writer, and we'll do it in a Q&A, so you don't have to worry about any snarky, sarcastic, or dismissive style. We'll print it verbatim as a Q&A.” Jimmy suggested Cameron Crowe because Cameron had interviewed him in 1973 for the L.A. Times.

TONY MANDICH When Cameron showed up at the Atlantic office to interview Led Zeppelin, I thought, “This kid must have come to pick up a poster or something.” But he really smoothed out the relationship between Rolling Stone and Zeppelin.

DANNY GOLDBERG Cameron was never one of the snobbish critics. He was like a champion, a cheerleader for music he loved. There's not a mean bone in his body, either as a writer or as a person. So he was not similar in temperament to the Rolling Stone or New York writers. Jimmy thought of the next generation, and he thought of Cameron and suggested him, and I was freaked when I was told that this kid in high school was going to interview them. But I went with what they wanted, and it turned out to be a very good thing for the band.

Zeppelin just wore everyone out with their success and the sheer fact of what they were doing. One way or another, it was going to wear down the resistance. There were too many people who love rock 'n' roll who loved Led Zeppelin for it to be ignored.

• • •

JAKE RIVIERA (manager of Dr. Feelgood) Ahmet and Earl McGrath and all the strippers were at Earl's Court. The band were pleasant to us because they were courting Dr. Feelgood. Robert was very nice, talking about “Riot in Cell Block No. 9” and Big Joe Turner. Jimmy loved Wilko's lead-and-rhythm playing, and they had a good old chat about Mick Green. But Lee Brilleaux didn't like the hierarchy of it all. Even at that point they were strutting around, and Bonzo was being boorish.

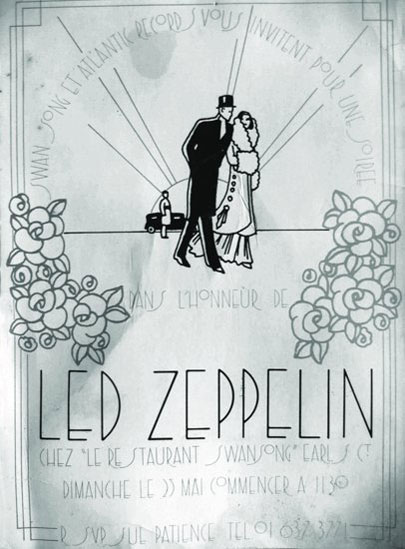

Invitation to the Earl's Court after-show party, May 25, 1975. (Courtesy of Phil Carlo)

ROSS HALFIN (photographer and friend of Page's) Earl's Court was more of an event than a week of great concerts. “No Quarter” went on and on and on, and the sound was very boomy. And all the songs from Graffiti were epically long.

DAVE LEWIS (editor of Zeppelin fanzine Tight But Loose) On the last night, they played for three hours and forty minutes. They did “Heartbreaker” and “Communication Breakdown” as extra encores, and played a reggae improvisation in the middle of them. They seemed to be in their own little world, oblivious to the 17,000 watching them. It was astonishing. Tell me that's not the greatest band that ever lived. When they walked off the stage, it was the end of the glory days. Nothing was ever easy again.