19

Turning into the Storm

They're like a lot of those groups. Not only aren't they doing anything new, they don't do the old stuff so good, either.

—Bruce Springsteen to Dave Marsh, Creem, October 1975

RON NEVISON (engineer on Physical Graffiti) It was the time of coal strikes and power cuts and oil embargos, and the Labour government closed all the tax loopholes, so everyone was leaving. I fled, too.

PETER GRANT Joan Hudson told us of the massive problems we would have if we didn't go. It was an 87 percent tax rate then on high earners. Disgusting, really.

SHELLEY KAYE (manager of Swan Song office in the U.S.) They were vagabonds for more than six months of the year, but they also couldn't live anywhere else for more than six months. So we were very, very careful to count the number of days. If they went over 181 days in the United States, they would have been subject to U.S. tax.

BOB EMMER (publicity director in Atlantic's L.A. office) Bob Greenberg called me and said, “We've got to find some houses for Zeppelin.” I spent a day with a real estate agent taking me 'round rental houses in the Malibu Colony.

BENJI LeFEVRE (Zeppelin sound technician and assistant to Robert Plant) Robert went along with the whole tax-exile thing because it seemed like a good idea, and they'd all signed up to it. It was like, “We'll make it work. We'll find a way to write some music, and we'll make a new album.” We had five houses that we rented in the Colony, one for each member of the band and one for G. The house Robert and I stayed in was right in the middle of the Colony, and when El Niño raged for days and days, it took all the sand away from the beach, and a couple of houses collapsed.

Every single day I would drive Robert into L.A. for physiotherapy for his arm and his ankle. There was lots of smoke and lots of Charlie, and I said to him, “You've got to slow down, man, because otherwise you're not going to get better.” So we had an agreement that if he did his physio, I would dispense a certain amount of drugs.

He and I became very close because I was with him 24/7. I mean, I had to lift him into the bath. So there was nothing we didn't talk about or know about each other. At the same time, in Jimmy's house up the road it was closed doors and closed curtains. We used to refer to it as “Henry Hall.” Robert started to get very disillusioned about the whole thing. It was a time of real reflection for him.

NICK KENT (writer for NME) By 1975, half the group was getting fed up with the debauchery. Page was sequestered with Krissy Wood, so there wasn't even much serial infidelity anymore.

UNITY MacLEAN (manager of Swan Song office in the U.K.) Robert had been so good to Jimmy. They were in a greasy spoon in London once, and Jimmy was so out of it that he couldn't get the sugar into his tea. Robert would pick up the sugar and put it in his tea and stir it for him. He was very soft and very kind to Jimmy.

ABE HOCH (president of Swan Song in the U.K., 1975–1977) Jimmy liked Mandrax, heroin, and Dilaudid. I went to see him once in Malibu, and he was lying on the bed naked, sprawled out unconscious. I came back, and Peter said, “Did you see Jimmy?” I said, “I did.” He said, “How is he?” I said, “I've seen more movement in a Timex.” Peter wrote that down. He said it was the funniest thing he'd ever heard.

MICHAEL DES BARRES (singer with Swan Song band Detective) Jimmy and Robert really weren't communicating with each other that much. It was very much along the lines of “Tell him yes.” Everybody had their own little posse—Rodney and Richard Creamer and Lori. Meanwhile, Jimmy was isolated with Freddy Sessler, the Dr. Nick of heavy metal.

NICK KENT Jimmy told me a lot about Sessler. Freddy was Keith Richards's best friend. Fuck, if someone gave you an ounce of pure cocaine every month, he'd be your best friend. When the Rolling Stones weren't around, Freddy would be with Led Zeppelin. And if Zeppelin weren't around, he'd be with the Who. And if the Who weren't around, he'd be with the New York Dolls. He was an ugly old guy who wanted young girls.

ELIZABETH IaNNACI (artist relations, Atlantic's L.A. office) In one of my few real conversations with Jimmy, we were at the Rainbow, and he asked me why I'd split up with my husband. It was a complicated answer, but I finally said, “The truth is, I loved him more than he loved me.” And he said to me, “Oh my, aren't we the martyr.” I almost stopped and said, “Who made you dislike women so much?”

All the women these men came into contact with wanted something from them, other than conversation and companionship. It was all about fucking the star, rubbing up against this bright light to get some of that shine on you. I really, really, really got it in that moment, and I would have liked to take Jimmy by the hand and have him meet some real women. But that wasn't going to happen—because he didn't know they existed.

RICHARD COLE Ray Thomas was looking after Jimmy—he was Jimmy's accomplice. And Bonzo was really out of control in Malibu. Mick Hinton was there with him.

PHIL CARLO (roadie for Bad Company) We had a couple of FBI men and a couple of Pacific Coast Highway department cops who'd park in front of each house every night and get paid for sleeping there. One night we all went into Hollywood, and we got this phone call from Bill Dautrich, the FBI guy who'd been doing the rounds. He'd spotted the light on in Robert's house, so he went in, and it was two of the Manson girls sitting on the bed, with all of Robert's clothes on.

ROBERT PLANT The L.A. musicians who lived in Laurel Canyon avoided us. They kept clear because we were in the tackiest part of town with the tackiest people, Rodney Binghenheimer and Kim Fowley. I wanted to know about the history of the Hollywood Argyles or who the fuck the Phantom was on Dot Records singing “Love Me,” and I would never have found that out at a candlelit dinner in the Canyon. Those people didn't come out from Laurel Canyon to see us at the Forum, because it was mayhem. For me, it was much more relevant to go out to the beach and spend time in the Colony than to be in the canyon.

KIM FOWLEY (L.A. producer and scenester) I had two wild girls in the car, and we were going over to Robert's house in the Colony. So we walked in, and Robert had over twenty women in the house. It looked like a cattle call for Paris fashion week. He had surf goddesses; he had Euro, Asian, black; he had tiny, tall, tattooed; otherwise, it was just Robert and some roadies. And Robert just wanted to talk about obscure records.

The girls I was with were rock 'n' roll beasts, and they got tired of sitting there with these other bitches while Robert discussed vinyl. They were also bisexual, so they decided to put on a lesbian floor show. It was like wrestling or something—everybody started yelling and screaming. And Robert said, “I don't need to see this, let's go outside and talk about Jill and the Boulevards.” So we went outside, and Robert told me he was willing to pay $25,000 for one of their singles: “Please say you know about it.” I said no. He said, “By the way, are you in love with either of those girls?” I said no.

The next day, one of the security guys called me. Robert wanted to invite the blonde girl to come back to Malibu. I turned to her, holding the phone, and said, “You got lucky—Robert Plant sent for you.” She was a surf goddess from Huntington Beach and quite beautiful. The next day I got a call from the security guy, saying that she'd insulted two female friends of his who'd shown up. Apparently, she'd said, “Why are these bitches here? I'm supposed to be with you tonight.” And apparently Robert said, “These girls are friends of mine. I don't make love to every woman I meet—and that includes you.”

I think Robert was a connoisseur of women. Wouldn't it be interesting if he'd studied all those women and then put their physical movements together with his old vinyl blues records—and if that was the whole Zeppelin stage show right there? Could that have been the secret of Robert Plant?

ELIZABETH IaNNACI Robert called the Atlantic office, and I answered the phone. I said, “Oh! How are you feeling?” I think he was quite nonplussed by that.

JANE AYER (press officer in Atlantic's L.A. office) He was in a wheelchair with a cast, but Benji would wheel him into the office, and it was like royalty coming in. I never saw the problems with Jimmy, but I was aware that something was going on.

ELIZABETH IaNNACI Occasionally, Jimmy would need some money. He would need $2,000, and I was making £200 a week. They were looking at houses that cost $5,000 a month to rent, which was half my yearly income. Plus, I had a little boy who was Karac's age, and sometimes Robert would come and pick me and David up in the limo, and David would fall asleep in his hotel room. Robert was always lovely around children.

Robert was very protective of me. There was never anything romantic between us, but there could easily have been. We spent many long nights where we would talk—or I would listen—all night. We talked about everything, his experiences coming up in the music business. It was never gossip, it was just about experiences. Everyone thought I was sleeping with him, because I spent a lot of time in his room. But it was unbeknownst to me, which is how naÏve I was. Even my boss thought I was sleeping with Robert, which was absolutely fine with him as long as the boys were happy.

On one occasion, I told Robert I was going over to the hotel to drop something off for Jimmy, and he just stopped me for a moment and said, “You know, Jimmy has a dark side.” It was all he said, but the point was taken.

MORGANA WELCH (L.A. groupie and Zeppelin friend) I spent a bit of time with John Bonham and got a whole other sense of a very nice man, rather than somebody you just wanted to avoid. They were at the Beverly Wilshire, and he must have had a kitchen, because we went to Safeway in Beverly Hills and got pulled over by the police for speeding. I fixed him breakfast. It was nice sometimes just to give something back to the musicians, and a home-cooked meal meant something. It was almost like a maternal instinct.

JANE AYER We'd go to the Rainbow; we'd go to Trader Vic's, where Robert had to wear a borrowed jacket that didn't fit him. I saw Little Feat with them in Venice. I saw Bob Marley at the Roxy with Bonzo, Ringo, and Keith Moon, and I had to pinch myself, thinking, “I'm sitting here with the three greatest rock drummers in the world.” I used to watch Marx Brothers movies with Bonzo, and all of them were heavily into Derek & Clive and Monty Python.

ELIZABETH IaNNACI Robert coped by actually surrounding himself with a few people who were grounded. I was certainly a spark of … if not sanity, at least hope.

ROBERT PLANT Everybody was aware there was a crisis in the band, so we got together and went forward as if nothing had happened—like turning into a storm instead of running from it. In L.A., we just rehearsed and rehearsed. It was so strange for me the first time because … I was sitting in an armchair singing, and I found myself wiggling inside my cast.

PETER GRANT There was a lot of tension about that period, [with all of us] all holed up in houses we didn't really want to be in. In fact, John moved out to the Hyatt House…. “Tea for One” sums that period up for me, really. That was Maureen's song. She used to come out at weekends, and Robert was pretty depressed.

JIMMY PAGE It's true that there are no acoustic songs [on Presence], no mellowness or contrasts or changes to other instruments. Yet the blues we did, like “Tea for One,” was the only time I think we've ever gotten close to repeating the mood of “Since I've Been Loving You.”

JOHN PAUL JONES It became apparent that Robert and I seemed to keep a different time sequence [from] Jimmy. We just couldn't find him. I wanted to put up this huge banner across the street saying, “Today is the first day of rehearsals.”

Myself and my then roadie Brian Condliffe drove into Studio Instrument Rehearsals every night and waited and waited until finally we were all in attendance, by which time it was around two in the morning. I learned all about baseball during that period, as the World Series was on, and there wasn't much else to do but watch it.

ELIZABETH IaNNACI When they decided to go to Munich to record the album, I got each of them a present. I made Jimmy an amazing wizard's hat—the front of it was a satin appliqué that I had gotten off a blouse the Fool had made. I'd cut the blouse apart and put it on the front of the hat.

I got Bonzo a wind-up racing car called the John Player Special, and I got Robert an amazing book of fantastic stories at the Bodhi Tree. Jonesy's present was this beautiful leather-bound book. I walked over to him and said, “This book is representative of our relationship.” He opened it up, and it was blank. It wasn't that John Paul was shy, nor was there a disdain. It was that he didn't waste his energy. And his ego was as right-sized as it was possible to be in that situation.

MITCHELL FOX (staffer at Swan Song in the U.S.) There were times when John Paul flew commercial with his family. He felt comfortable with that. There was a spotlight on Led Zeppelin at all times; it was just whether you stood in the spotlight or not. Onstage, John Paul was as much a star as anyone else. Offstage, he took the low road.

ELIZABETH IaNNACI Just before they went to Munich, we had been hanging out at the Record Plant, because a lot of people were recording there. One particular night, Robert and most of Bad Company were there, and everybody just kind of picked up instruments and started to play. We were all singing along to “Stay” by Maurice Williams and the Zodiacs. It was so much fun. We dubbed it “The Night the English Left Town.” The next day, Peter Grant demanded the recording. He didn't want it to fall into someone else's hands.

• • •

RICHARD COLE John wouldn't do his tax-exile trip abroad because Pat was having a child. He and I flew to Munich from London, and the others flew in from L.A. When we got there, they'd been [in Germany] two days before us, and it was very cold. But one of the crew was laughing and giggling. I said, “You don't seem very worried by the cold.” And he said, “No. We've found the solution.” And he pulled out a bindle of heroin. “That'll warm us up,” I said.

JIMMY PAGE [Presence] was recorded while the group was on the move, technological gypsies. No base, no home. All you could relate to was a new horizon and a suitcase. So there's a lot of movement and aggression—a lot of bad feeling toward being put in that situation.

JOHN PAUL JONES There were good times and … frustrating times. The band was splitting between people who could turn up on time for recording sessions and people who couldn't. I mean, we all got together and made the album in the end, but it wasn't quite as open as it was in the early days: what band could be, after all that time and the amount we'd been through?

These days, everybody knows so much about helping people and what goes on, but in those days, you kind of didn't, really. And while you'd say, “For Christ's sake, don't do this or … be here then,” you didn't really know enough to start telling people how to live their lives. You didn't know whether what you were doing yourself was totally the right thing. But we were beginning, I suppose, to think, “Well, wait a minute, it may be coming apart more than it should.”

ABE HOCH We go to make Presence, and they ask me to come to Munich. We get to this hotel called the Arabella, and we're in the basement of the hotel. Keith Harwood, the engineer, is there. Robert is hobbling about on a cane, and he's lying in bed a lot. He's writing lyrics for this record that we were supposed to do that seems to never happen because Jimmy is not awake. They set Bonzo's drums up in the dining room, and he drives out all the diners, but nothing is happening. Robert is saying things to me like, “What rhymes with Achilles?”

ROBERT PLANT ”Achilles Last Stand” was prog rock gone mad, and it was brilliant. I remember when we wrote it, it was such a beautiful bird to release. It was about going back to Morocco and getting it back again. The music was stunning, and when we did it live some nights, it would be unbelievable, and other nights it was dreadful. But at least it wasn't “Great Balls of Fire.”

ABE HOCH One day Jimmy wakes up, ruffles his hair, goes into the studio, and starts to fiddle around on the guitar, and it reverberates information around the building, which is that he is in the studio. Jonesy and Bonzo run like demons to the basement. They play together and bring food in, and seventeen days later we have this record.

I don't care what illusion anyone has about the process, it was so remarkable to watch as a casual observer, because it looked like a jam, and it wasn't. It was well-crafted, beautifully articulated songs that didn't have the whole verse-bridge-verse concept, and yet you could walk away humming and singing lyrics to them. It was the most bizarre thing you ever saw.

JIMMY PAGE There are certain times where people would say, “Oh, Jimmy wasn't in very good shape.” Or whatever. But what I do know is that Presence was recorded, finished, and mixed in three weeks, which was done on purpose not to mess about.

ROSS HALFIN (photographer and friend of Page's) Presence is Page's favorite Zeppelin album. I personally can't bear “Achilles Last Stand,” I think it's so pompous. To me, it's everything that's wrong with Led Zeppelin. But it's a very metallic album, and that's what Jimmy likes about it.

GLENN HUGHES (bassist and singer with Deep Purple and Black Country Communion) When people abuse drugs and alcohol that much, they lose their muse. You can hear the blow and the horse on the later Zep stuff, just as you can hear it on the Deep Purple albums and the Stones albums. There are moments on Presence that I really like, but for me, the peak was Graffiti.

JAAN UHELSZKI (writer for Creem) Lester Bangs used to say he could always tell when someone was on a particular drug when they'd written an article. And Presence feels like an album made on painkillers, which, of course, Robert was.

RICHARD COLE After we made Presence, Peter and I flew to Paris to bugger around with Abe Hoch. Then we met up with Jimmy in Los Angeles. I flew home with Jimmy because Scarlet was in a pantomime at school. Then they all met up in Jersey again. I think they got the plane home on Christmas Eve. And then Bonzo became a tax exile in the south of France.

ABE HOCH Po from Hipgnosis came up with the plinth. We didn't know what it was called, everybody just said “the object.”

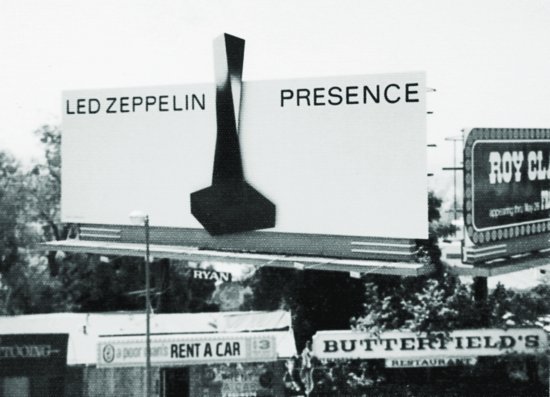

Led Zeppelin make their Presence felt on the Sunset Strip. (Courtesy of Phil Carlo)

AUBREY POWELL (designer of Presence sleeve) When we did Presence, Steve Weiss sat me down and said, “Po, you've designed this black object, and we've got to think about how this is gonna be perceived by people.” I'd sit there for hours with Steve, pontificating about what the design was going to do.

The best thing about Steve was that he held the power of Peter Grant and Led Zeppelin in America. When I was trying to get Atlantic to approve album covers and other things, I'd call Steve and say, “They're fucking me around.” And he'd get on the phone and say, “Po has the authority from Peter and the band to do whatever is necessary to get this artwork right, and you fucking do what he asks.” He was a very powerful spokesman.

He was also the guy who got everybody out of trouble, whether it was Led Zeppelin or Bad Company. Some bad stuff went down with Bad Company—I was there when it happened—and Steve was the first guy on the plane down there to sort it out. He certainly knew where the bodies were buried.

SIMON KIRKE (drummer for Bad Company) A bouncer in a bar in New Orleans threatened Boz Burrell with a blackjack, and they all set on this guy and beat him badly. I believe he lost an eye. They were all arrested and spent the night in jail. Strings were pulled and money was paid, but Bad Company never played New Orleans again.

ABE HOCH Captain Fantastic and the Brown Dirt Cowboy had come in at No. 1, and that was a big achievement. It was one of the first times an album had come straight onto the American music charts at No. 1, and they really didn't want to not have that happen with Presence. Danny Goldberg and I devised this idea for the record to be released worldwide simultaneously, at the exact same hour, minute, and second. It was a massive feat of coordination, but it worked. So the record came in at No. 1 on one chart and No. 2 on other charts.

DAVE NORTHOVER (John Paul Jones's assistant on Zeppelin's 1975 and 1977 U.S. tours) Benji and I were looking after Robert in New York, and we received a phone call around three in the morning from Jimmy. Could I come up straight away? It was really important.

BENJI LeFEVRE Jimmy said, “Where's Northover? I need Northover right now!” I said, “Actually, he's in my room here with me.”

DAVE NORTHOVER So we got up to his room, and there was Jimmy at a desk, and Ray Thomas passed out in the corner. Jimmy was quite agitated. When he wrote, he always wrote with a fountain pen. And he had a bottle of ink on this desk, along with a little bottle of cocaine. By mistake, he'd emptied the pen into the bottle of cocaine, rather than into the bottle of ink.

He said to me, “Dave, can you separate the ink from the cocaine?” I could probably have done it, but it would have meant buying ether and various other things. So he gave me this foggy blue mess, and I dried it out on a hot water cylinder. For the next few days, we kept seeing these people coming out of Jimmy's room with blue snot.

BENJI LeFEVRE After the Blue Charlie episode, we flew to L.A., and Bonzo got really, really drunk before we took off—so drunk that he pissed the seat. Hinton was sitting in the row behind, and Bonzo said, “Hinton! When I stand up, you've got to stand up and follow me to the toilet so no one can see I've pissed myself.” When they came back from the bathroom, Bonzo made him sit in the wet seat for the rest of the flight.

GLENN HUGHES I knew Pat Bonham as a friend. When John was touring, Pat's sister Beryl worked behind the bar at the Club Lafayette in Birmingham, and we'd hang out. There were never any shenanigans. We were just mates, and we liked to have a couple of cocktails.

What happened was that John heard something other than that, and he was very upset about it. It was just a vicious rumor. Truly, nothing happened. Pat adored John and thought the sun shone out of his bum. All she wanted to talk about was John, John, John, John. But he heard different, and he was very upset by it, because we were really good mates.

John and I went out and had a few cocktails, and we cried and we laughed and we hugged, and we ironed it all out. Then Trapeze were playing at Radio City Music Hall, and Zeppelin were in town. Bonzo had the bowler hat on, he was in full Clockwork Orange mode. My friend was unhinged, and he had that look in his eye that something was about to kick off.

I was fucking frightened, but I loved this man, and I wasn't about to lose a friendship with him over something as serious as having a relationship with his wife. I've never been a cocksman, that's not part of my story. He kept saying, “What 'appened? What 'appened?” Nothing happened. I've been there myself: I know cocaine paranoia, and I know what it's like.

That morning I did a runner after he passed out. He was getting pretty mad again.

• • •

ABE HOCH Peter said to me, sitting by the fire one night, “We'd like you to come and run our record company.” I said, “What does the job entail?” He said, “Oh, you'll know.” I said, “What do you mean, ‘I'll know'?” He wasn't very descriptive. But I thought, “Wow, this is an opportunity to run a record company for the biggest band in the world.”

I go to New York—leaving my wife and kid in California because we haven't figured out yet how to make the transition—and check into the Plaza Hotel, an enormous suite where all types of bacchanalia take place. But there's no band in sight. Zeppelin has gone, and I'm there waiting for them to tell me when I'm going to go to London. Word never comes. Peter is paying for everything. I had a huge suite with a pool table and a grand piano in it, and I was living the life of Riley on somebody else's dime. It was bizarre.

At the end of September, I get a call saying, “Okay, come to London.” I said, “Great.” I get on a plane and go to London, and I say to Peter, “Where will I stay?” He said, “You'll stay in my mews flat in Gloucester Place.” I said, “What's a mews flat?”

Carol Browne ran the show. It was Carol's company. So I got in and introduced myself. “Hello, how are you?” She said, “We've been expecting you.” I called Peter a day and a half later and said to him, “There is no record company.” He said, “See, I knew you'd know.” And he hung up on me.

ELIZABETH IaNNACI Everyone thought that the Pretty Things, with the strength of Zeppelin behind them, would explode. And nobody cared. As innovative as they had been years earlier, the music was ho-hum at that time.

ALAN CALLAN (president of Swan Song in the U.K., 1977–1980) The Pretty Things were signed purely as a musical adventure, to give them the opportunity to be creative. The trouble is, they would come along and think, “I'm on Led Zeppelin's label, so I can party.” I had to say to John Povey, “I'm not sure you have a future in this band. You should either leave or consider how this band is going to organize itself.” Mostly, it was just human insecurity multiplied.

SHELLEY KAYE By the time of Detective, Peter's involvement was definitely tapering off. The band wanted another hit act for the label, and they never got it. They didn't get it with the Pretty Things, and they didn't get it with Maggie or Detective.

MICHAEL DES BARRES Miss P and I were together, and they all adored Pamela. We got a band together, and it was super-loud and super-powerful. Every label wanted it, but we chose to go with the Zeppelin mystique—the greatest force in rock 'n' roll at that time. Jimmy's gonna produce? Oh my God, where do we sign?

For a year, we sat around getting more and more fucked up, with unlimited sums of money, waiting for Jimmy to produce. Eventually, he said, “Let's get Steve Marriott to do it.” And then it was another six months' waiting for little Steve. So much of rock 'n' roll is waiting on junkies to make up their fucking minds.

SAM AIZER (artist relations at Swan Song in the U.S.) Peter showed up on Bad Company dates less and less often. Clive Coulson would pull his hair out because he couldn't get Peter on the phone for days. When something like drugs own you, they own you. Peter had another master, and it wasn't Led Zeppelin, it was his own hell.

I once went to Elliot Roberts's office in California when he was managing Detective. He was looking for support from the label, he wanted answers: who was going to give him an answer? He said to me, “I'll bet you ten thousand dollars against your life you can't get hold of Peter right now. Would you call him and say, ‘Put Peter on the phone, or Sam Aizer's gonna be killed'?” I looked at him and thought, “He's got a point.”

DANNY GOLDBERG (president of Swan Song in the U.S.) When it came time to take a Swan Song signing photo, I got a limo to pick up Jimmy at the Malibu Colony [and] brought him to my room at the Beverly Hills Hotel, where the members of Detective were to meet us. Jimmy was nodding out the whole time we were in the car, and when we got to my room, he lay down on the couch and immediately fell asleep.

When the band got there, Michael and I tried repeatedly to wake him, even going to the extreme of throwing cold water on his face, but it was to no avail. Although he was breathing, Jimmy was out cold. After around a half hour, I had Andy Kent photograph Detective sitting next to the sleeping Page and then sent him and the band members home. A few hours later, Jimmy roused himself.

There had been rumors that he was doing heroin, and this behavior made me believe them. Not surprisingly, Page had a different explanation. He said he had taken a Valium and must have overreacted to it. He was furious with Michael and me, disbelieving that we had really tried to wake him. He let me circulate the photo but later complained that, in doing so, I had “made me out to be a twit.”

In retrospect, he was absolutely right. The photo should never have seen the light of day. Detective was lucky to be on Swan Song, and it would have been no big deal to schedule another photo session. I had forgotten who I was working for.

ELIZABETH IANNACI I don't think Michael was under any illusions about Led Zeppelin, and Detective wasn't a great band—we referred to them as Defective. My speculation is that he knew the music wasn't going to be enough to carry the band, so there was a level of feeling that they were on Zeppelin's coattails.

MICHAEL DES BARRES Talking about Swan Song is almost like talking about the Luftwaffe. It wasn't a record company, as far as I could see. I didn't see any ads or promotion for the Detective record. So I think it was an indulgence on the band's part. Rodgers and his crew had hits, but we didn't. Danny Goldberg became my brother-in-arms, but you couldn't get anybody on the phone.

You certainly couldn't get hold of Steve Weiss, who seemed to be some gangster lawyer on Long Island, while I was in West Hollywood with a bunch of decadent ne'er-do-wells. We were promised a support tour with Zeppelin, which was a huge thing. Never happened.

And then suddenly, guess what, the Sex Pistols show up, and I wanted to go out and be part of that. By the time the record came out, I was totally disengaged from the thing we were supposed to do.

MITCHELL FOX Frankly, as much as Swan Song was a record label, in retrospect it was really a management company. By the mere fact that Led Zeppelin were so big, they were given their own imprint, but it was a by-product of the fact that Peter and Steve looked after everything—publishing, merch, touring. It was really the quintessential 360-degree management deal.

SAM AIZER It was the American office that ran the Zeppelin operation. The office in London was just a great place for people to come hang out at.

UNITY MacLEAN I soon learned, after being there for a few months, that not much was going on. Led Zeppelin were paramount, the rest went down the pecking order. Swan Song had money that should have been used on the acts, and Phil Carson should have steered the label in that direction.

ED BICKNELL (former manager of Dire Straits) Peter told me Swan Song was the worst thing he ever did. He basically ended up managing all the acts on the label. As hard as you try, you can never train your acts to speak to the other people in the office—they only want to speak to you. If they've just gotten a parking ticket, they don't want to speak to the accountant, they want to speak to you. You can build a brick wall round yourself, but the artists will still find a way through.

Zeppelin could be on top of the pile, but they could still be professionally jealous of somebody. So you end up with the acts becoming competitive with one another within your own stable. And even if you get one act away—which they did, obviously, with Bad Company—you still have three others that are dragging the whole thing down.

RICHARD COLE Abe Hoch wanted to sign Iron Maiden, and I think Danny Goldberg at one point wanted to sign Waylon Jennings. But they couldn't sign anything because you had to get the five guys in the room together to sign off on it. So what did you do? You went to the pub and got fucking drunk.

DANNY GOLDBERG In May of 1976, Peter gave me the choice of giving up Mirabai's management or leaving. I don't think he expected me to choose an unknown act. But I was filled with the irrational confidence and self-righteousness of youth. As fierce as he was to outsiders, Peter romanticized his team and didn't like confrontation. “I never thought it would come to this,” he said, large tears dripping down his massive face.

“You know, all those friends of yours wouldn't talk to you if you didn't work for Zeppelin,” he'd ominously said to me not long before [this]. Peter, I felt, was also talking about himself. Jimmy Page virtually controlled his self-esteem.

JOE JAMMER (guitarist and Zeppelin roadie) I left the organization because Zeppelin got way too big and way too busy, and they were having trouble just staying sober and staying awake and staying alive. There had been a lot of love and a lot of care there, but the wrath of Satan was unleashed on others right around me. I knew I was going to end up like Maggie Bell, who was so loyal to Peter that she ended up as the receptionist at Swan Song. It was the only way she could see them as they rolled into the office.

ALAN CALLAN It wasn't as if you could say to her, “Look, Peter's not around, just go off and do it yourself.” Her attitude was always, “No, I need to talk to Peter about it.” I think it would have been really interesting with Steve Smith, who was at his hottest at that moment. He had a great relationship with Little Feat, and he had a great relationship with the guys in Muscle Shoals, and it would have been great to throw Maggie into that mix.

STEVE SMITH (producer of Robert Palmer and other artists) Jimmy's favorite band in the world was Little Feat—with whom I'd worked on Robert Palmer's Pressure Drop—so Alan approached me to produce Maggie. I thought she was an absolutely fabulous singer, so I said, “Let's do it.” He said I needed to fly to New York to meet Jimmy to get the royal seal of approval. The next day a ticket on the Concorde arrived, so I went over to meet Jimmy and Peter Grant to sign off on the deal. They put me in a suite at the Plaza, and I went to see Zeppelin at Madison Square Garden. I never even got around to meeting Jimmy. So it never happened with Maggie.

Bonham, Page, and Maggie Bell celebrate wins at the Melody Maker awards, September 17, 1975. (Central Press/Getty Images)

UNITY MacLEAN Maggie was in the office virtually every day, and we had a lot of fun and silliness together. At one point, Peter was supposed to book her some dates and get her an agent, but he never did a damn thing.

MAGGIE BELL (Swan Song artist) He never knew what to do, Peter. Nothing was ever good enough. It was always, “Let's wait, let's wait.” But he didn't want anybody else to run my career, either, so I was in a Catch-22.

ABE HOCH We had one Telex machine, and I would try to get to the Telex to move the product out there or try and get the promotion guys involved. One time, Robert had lost a robe somewhere in a spin dryer, and he wouldn't let me near the Telex, because the priority wasn't really to get this record placed but to get his robe back.

UNITY MACLEAN There was one nice piece of furniture in the office, which was an etched mirror of Wolverhampton Wanderers [Football Club]. Robert would stand in front of it and comb his hair. Cynthia Sach once said, “Oh, do look at Robert enjoying his two favorite things in the world.”

CYNTHIA SACH (secretary in Swan Song's U.K. office, 1977–1981) Robert was a bit of a whinger. He'd studied accountancy, so he was well into the figures. A bit preening, because he had that beautiful hair like the golden fleece. He loved Wolves. For his son's birthday, he wanted me to get him a black and gold Wolverhampton Wanderers cake.

MARILYN COLE (wife of Richard Cole) Abe Hoch was a nice Jewish boy from the States, and they cut his bollocks off from the word go. His hands were totally tied, so he couldn't do anything. There was abuse everywhere, and it escalated like a mushroom cloud.

SIMON KIRKE Drink and drugs took their toll not only on Bonzo but on Jimmy, Peter Grant, myself, Boz Burrell, and—to a lesser degree—Mick Ralphs. Coke does terrible things to people over a long period of time. Lack of sleep adds to the paranoia that coke induces, drinking escalates, and the brain turns mushy with the downers that a lot of users take to get some form of sleep.

MARILYN COLE There was a dealer down the end of the King's Road named Byron. He was very near the office in that golden triangle of pubs: the Roebuck, the Water Rat, the Man in the Moon. He had a shop there, and you scored in the back office. Richard and him were tight, tight, tight.

BENJI LeFEVRE It was always, “Let's go back to the office and do some more drugs. Or let's go up the Water Rat. Oh, look who I've met, Johnny Bindon. He's a real laugh. Someone's on the phone? I'll talk to 'em tomorrow … they'll always come back because of who we are.”

UNITY MacLEAN There was some girl calling up to Swan Song from the street: “Richard! Richard!” And he shouted down, “Clear off, you old skank!” “Please, Richard, open the door!” “I told you to fuck off!” And he opened the window and peed on her head.

PHIL CARLO It wasn't an office where anybody went in at 10:00 a.m. It was waifs and strays and heroin dealers and odd people, a bit like the American tours but a scaled-down version. The Colonel with his mustache and blazer, like the Major in Fawlty Towers sorting out the poppy tins. Dealers in dark glasses, girls in flowery dresses, people with pit bulls who came along with John Bindon. Terry DeHavilland, the shoemaker. Vicki Hodge, who—when she got pissed in the Water Rat or the Man in the Moon—would lift her skirt up and moon anyone who was walking up the King's Road, while Bindon roared his head off. They were very strange days.

MAGGIE BELL Carol Browne had an argument with Peter. It should never have happened, because Peter loved Carol, and Carol loved Peter very much, but it was going a bit crazy and Peter was under a lot of pressure. A call came through from his son Warren, and Carol failed to give the message to Peter straight away.

UNITY MacLEAN Peter was being more and more offensive to Carol. And if she made a decision on his behalf, Peter would phone her up and chew her out left, right, and center. She got to the point where she didn't want to take any more of it.

MAGGIE BELL She walked out. She never got a penny. She held her head high, walked three streets up to Lots Road, and started a secretarial service.

UNITY MacLEAN I was absolutely shocked. I was like, “Carol, come on.” And she said, “If you'd been through all the stuff that I've been through, you'd have some self-respect, and you'd leave, too.” I sat back and thought, “She's right.” People say, “What an incredible manager Peter was, he really wrung the last buck out of everybody for his group.” But why put people through the misery he did?

MAGGIE BELL Unity took over from Carol. Cynthia was wonderful as well, but she was as soft as butter and not for that office.

CYNTHIA SACH Jimmy only wanted to talk to me at the office. He knew I was straight-talking and not in awe of rock stars. He appreciated the fact that I wasn't a sniveling, groveling fan. I wasn't terribly impressed by Swan Song. With all their money, the offices were so scruffy.

PHIL CARLO Dolly the cleaner was over eighty and about four foot eight and always wore a black dress and didn't have any teeth. She'd known G for a long time, and she used to tell him off. If it was a really cold day, she would say, “That boy's been in here again with no coat on. He'll catch his death of cold.” G used to love it.

One day we were all in the office talking, and Dolly said, “We've 'ad trouble with people lurking about in the flats.” She lived in the council flats across the road, and there'd been some yobs hanging about, causing trouble. So G said to Richard, who was there with Terry DeHavilland, “You'd better go home with Dolly and make sure she gets in alright.” Dolly turned round and said, “Don't worry about me, son.” She put her hand in the carrier bag and pulled out the handle to a mangle [a clothes wringer]. Terry went, “Fuck me! Dolly's tooled up 'n' all!”

CYNTHIA SACH Warren Grant and Jason Bonham used to sit outside the office, writing notes and throwing them out the window at the postman. The notes said, “Postman, we think you're a bastard.” Unity told them off. I would take Helen to the ballet at Covent Garden for Peter, and he bought me a dress to thank me for it. Helen was a lovely kid, but Warren was a little monster.

UNITY MacLEAN Peter would ask me to take Helen out to lunch, because he wanted Helen to know which knife and fork to use. I did take her out a few times, and she was actually a happy little girl. Peter gave her everything she wanted.

Dan Treacy Peter was like Shrek meets The Long Good Friday. Unity sent me to cash a check for £350 at Swan Song's bank in Mayfair, and I accidentally went to the wrong branch. The cashier refused to give me the money. When I got back to the office, Grant came stomping up the stairs, lifted me up, and pinned me to a wall. He goes, “You've really fucked it up for me and Jimmy, you little bastard.” Then he let go, and I slid down the wall. I later found out that half the money was for a dress for Grant's daughter, and the other half was for a bike for Page.

ABE HOCH Jimmy would stay over and sleep on my floor and be maudlin about what to do with his relationship with Peter—and whether he wanted that to continue or not. He would open up to me, and then I was stuck with the information. Because what could I say? I'm a loser either way.

He would sit me down and say, “I think the band will need to make a move against Peter.” Now that I look back on it from a rational perspective, it was more a test of me and how I would play it. It was manipulative, because either way, I get the boot.

I said to him, “Leaving him is not the way to help him. That will drive him further into the toilet. You need to be a friend and an ally, rather than an adversary here.” I think that cemented something for Jimmy, because at least I didn't look at it as an opportunity for myself but as a loyal and caring friend. Jimmy may have been serious and I'll never know, but in advising him, it may have just stemmed the flow of what he was feeling at that time. It was a test. It was always a test.

Everything about Swan Song was a game. Just being involved in it was a game.