20

A Powerhouse of Madness

Everyone's a bloody roadie or something, and they're all terrified of Grant. It's sickening just to observe those people crawling around. Just seeing all that—just having to be around it all—was enough to make me want to leave.

—Nick Lowe to Nick Kent, New Musical Express, July 1977

BP FALLON (Zeppelin's U.K. press officer, 1973–1976) They all thought it would be cool to have Dave Edmunds on the label, so I went down to Rockfield and talked him into coming to Swan Song.

UNITY MacLEAN (manager of Swan Song office in the U.K.) It was perfect because Dave wanted to rekindle his career. And I remember saying, “That's a good idea, because he's going to bring fresh breath to Swan Song—he's going to lighten us up from the Pretty Things and Maggie Bell and Led Zeppelin.”

DAVE EDMUNDS (Swan Song artist, 1977–1982) It was heaven, from an artistic point of view. Besides the figures involved, which were generous, it freed me from the usual hang-ups that artists have with labels. The boys were interested in what I was doing but wouldn't interfere.

ABE HOCH (president of Swan Song in the U.K., 1975–1977) When they signed Dave, they sequestered him in the Gloucester Place mews house. I remember standing outside, knocking on the door and saying, “Can I come in?” They went, “No, go away.” I went, “That's it, I'm done.” I called Peter in Paris and said, “I want to quit.” He said, “Well, we refuse to accept your resignation.”

UNITY MacLEAN Peter did nothing for the Pretty Things, and nothing for Dave. One night my husband, Bruce, came over and told Peter that all he had to do was pick up the phone to Asgard and just get Edmunds a support slot. A couple of days later, I called Peter at Horselunges, only to be told that he was not available and would call me back. He never did.

This was the heartbreak that Dave would come to know. The realization that this was the end of the road, not the beginning, must have been awful. One night Dave, Bruce, and I were shooting the breeze, and Dave said, “Perhaps I could get out of my contract.” “Perhaps,” I agreed, knowing that you don't leave Swan Song. You're not going anywhere. You wait till the contract is up.

ABE HOCH I'm in the third-floor office, and I'm informed that Peter wants to see me. I go in, and everybody is going home because it's the end of the day. Peter gets up and locks the door behind us. He goes, “You wanna quit?” He opens his briefcase and takes out a pound of cocaine and puts it down and says, “Let's talk about it.”

We never leave the room. I'm white, and I can't see anymore. After three days, I'm like, “Oh, I'll give it some time, you know.” I just want him to let me out of the room.

I stayed and allowed myself to deteriorate as a person, both financially and creatively. I was really in a bad place. I find it sad to this day that all of the guys, like Mick Hinton and Brian Gallivan, they all died in poverty. Richard Cole ended up in a council flat. There's a better way to take care of your own.

MARILYN COLE Richard was married to the band. If he'd met me halfway, maybe we could have got somewhere. But I realized he was just always going to be working for Peter Grant on salary. And I was very unhappy. I had already done quite a lot; I'd traveled, I'd lived in Positano in the '60s. I hadn't aspired to being with someone who was going to stay in the same job like a bank manager for the rest of his life. Having said that, I loved him in my mad way.

RICHARD COLE It was a very difficult position. You weren't always getting the cash in hand, but I'd get exactly the same hotel suites and treatment as they got. It was a lot better than erecting scaffolding. If you end up with nothing, you end up with nothing. I could have left any time, and maybe I should have done. The sensible ones got out.

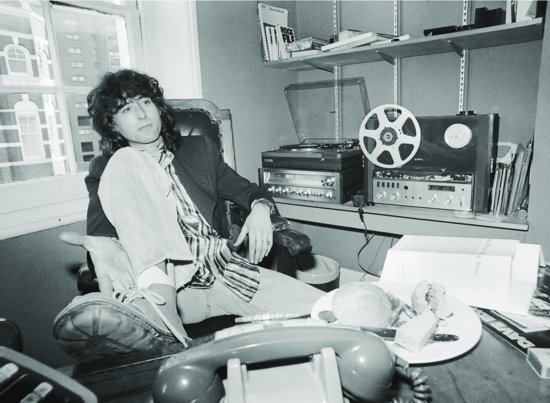

Page on the top floor of Swan Song, New King's Road, October 1977. (Ray Stevenson/Rex Features)

ALAN CALLAN (president of Swan Song in the U.K., 1977–1980) One day Jimmy just called up and said, “What are you doing? Would you like to come and run Swan Song?” I said, “Sounds great, Jim. What are you talking about?”

RICHARD COLE Out of the blue, Jimmy and Peter turned up one day with Alan, and we were told he was going to be running Swan Song.

UNITY MacLEAN The first thing Alan did was paint the office upstairs red. I said, “My God, whatever did you paint it that color for? It's so dark.” He said, “So it won't show the blood.”

ALAN CALLAN The one thing we should have been famous for is a sense of humor. I can't tell you the countless number of times people came up to Peter and said, “G, I hear you've got a grudge against me.” And Peter would go, “Don't worry, it's all forgotten now.” The guy would leave, and Peter would say, “Any idea who that was?”

MAGGIE BELL (Swan Song artist) It was a strange situation with Alan. He started ordering everybody about. I said, “Excuse me. Who are you?” He says, “I'm in charge of you. Anything you lot want to do, you ask me first.” I thought, “He can fuck off as well.”

ALAN CALLAN Peter's assumption was that I'd already started just by having the phone call. So I said, “What's my job?” He said, “Go and see Ahmet, come back, find artists, and sell records.” Ahmet said, “To tell you the truth, Alan, if you call me and tell me you want to sign a kid who shakes matches, I'll pay for it. This band is that important to us.” He said, “I've built Atlantic's international offices on the back of Led Zeppelin's cash flow.”

He said to me, “What do you want to do?” I said, “Well, before I go too far, I want to sign a great artist, so we can make our mark as a label.” I thought John Lennon was the greatest unsigned artist of the moment. He was sitting in New York, doing nothing. And for nine months, maybe longer, I kept phoning and asking, “Can we meet? Can we talk?” It went from “Fuck off” to “Okay, I appreciate that you keep calling,” to David Geffen just walking in and offering him an enormous amount of money. That was the one moment when I would have liked Peter and Jimmy to have phoned another artist and said, “Come on our label.”

PETER GRANT What I regretted about Swan Song was not getting someone in to run it properly. We kept getting it wrong, or I did. It didn't work with Abe Hoch, and in America, Danny Goldberg became another pain in the ass. I think if we'd had Alan in from the start, it might have been okay…. In the end, he fell foul of Steve Weiss's ego problems.

ALAN CALLAN Steve was the only Italian-mobster Jewish cowboy in New York. He was also the only one in that organization that I thought was not a straight shooter. He was the Salieri in the mix. He was obstructive, mostly because he wanted something out of the deals for himself that was outside of Swan Song. Weiss's ego was the thing that distracted Peter and Jimmy—the way he fucked Zeppelin around with Atlantic. That was why I couldn't get anything happening with Maggie. It was like, “Alan, we just can't go there right now.”

UNITY MacLEAN Steve was a very smart man. Very suave and very cool. A shadowy figure and probably the brains behind the whole operation. I would only hear whispers and rumors about him and his circle of cronies: he was connected, and he knew how to get 'round the unions and all that that entailed. I met this DEA guy once, and when I told him I'd worked for Led Zeppelin, he said, “Oh, yeah, we helped those guys out a lot. It was the only way I could get my daughters tickets for the concerts.”

SAM AIZER (artist relations, Swan Song in the U.S.) Steve was a prick. This was not the kind of guy you would invite over for a meal. He was an egotistical, insecure man who was a bully. And he was able to be a bully because of the clients he had.

ALAN CALLAN I had one incident in London when Steve came over. I went to meet him at the Montcalm Hotel, and he started off on one of those “Do you know who you're talking to?” numbers. So I walked downstairs, paid his bill, and told him he was leaving. And I went back to the offices and told Peter, who gave me a round of applause. Because whenever anybody got too close to thinking they could live off the band without laying the table, Peter was very anti that.

NICK KENT (writer for NME) Page couldn't stand Weiss. It was always, “What's that fucking Steve Weiss doing here?” They didn't like him basking in being a power broker in Led Zeppelin's world.

BP FALLON Swan Song wasn't a failure; it's just that there's a difference between running a record label and getting on an airplane to go to some gig with eighty thousand punters going crazy. Peter liked all that. Anyone would like it.

MAGGIE BELL It all got too much. Two years after Swan Song moved into 484 New King's Road, Mark London said to Peter, “I'm going.” He just left with Stone the Crows and some publishing he had. That was it, but the funny thing is, a lot of Mark's beautiful furniture was left in there.

UNITY MacLEAN I used to go and see Dave Edmunds's manager, Jake Riviera, who was the most sarcastic and difficult man. He hated Peter because of the way Dave was being treated, just loathed him. But he would take it out on me. I'd suggest a few things we could do, and he'd say, “Oh, where are you from, Unity? Are you from the sixties?” He reduced me to tears once. I think the hostility that many of the punk bands showed to Zeppelin sort of trickled down from Jake.

PETER GRANT Dave Edmunds and people like that, I just didn't have time to oversee them. Dave had Jake Riviera anyway, which brought its own set of problems.

ALAN CALLAN The unfortunate thing about Jake was that he really felt he had to compete with Peter. It was like, “I'm as important as Peter Grant.” In a way, Peter was quite chilled out, and then Jake comes in, and there's a lot of attitude.

SAM AIZER Jake was the angriest man of all time. It was him against Swan Song, him against the world. And sometimes you need that. Dave Edmunds needed it, because he was basically dicked around.

JAKE RIVIERA (manager of Dave Edmunds and the Damned) Unity and all that lot were very nice, but they couldn't do anything. They were hogtied, waiting on Peter and Jimmy. Alan Callan was nice but ineffectual. I'm coming from Stiff Records, where—if I like somebody—they go up to Pathway Studios, we record them, and we put the record out the next day. And here we have Swan Song, where Dave's album has gone back a month because Jimmy's trying to airbrush the devil into his hair on the cover.

UNITY MacLEAN Peter really dropped the ball with Dave, and it was a tragedy. So I understood why Jake was so angry.

JAKE RIVIERA It came to a head when we did Nick's Labour of Lust and Dave's album back-to-back in the studio. We were all burning out on a vodka-and-cocaine diet. So I say, “Let's do the Beatles in reverse and make a Rockpile album.” Edmunds's contract is coming up, and suddenly he's very amenable to me. He says, “You've got to tell Peter we want to do a Rockpile record.”

I'm busy, I'm shaking, I'm twenty-eight and on top of the world—the male ego holding court—and the phone rings. My assistant says, “It's Peter Grant on the phone,” and everything goes quiet. Immediately, I'm like, “Oh, hello, Mr. Grant,” very polite and subservient.“ 'Allo, Jake, I fink we need to talk.”

So I'm summoned to Horselunges to have a meeting about Rockpile, the problem being that Nick Lowe is already under contract to Columbia, whose executives are shit-scared of Peter. Ahmet and Jerry Wexler were good people, but Steve Weiss was a fucking slippery creature. On my way down there, I think, “What would Michael Caine do?” I'm going to do whatever I have to do to get Edmunds out of his contract.

Richard Cole rings and says, “D'you need a ride down there? I'll send a car.” Ten in the morning, he comes round in a Rolls-Royce with a chauffeur in a gray hat. I think, “This is intimidation, but if you wanna ride the roller coaster, you gotta pay the fare.” Richard says, “We gotta stop off at Jimmy's to drop some speakers off.” I'm not sure what sort of speakers you can get inside a big brown envelope, but we pull up outside Plumpton Place, and Richard says, “Stay in the car, don't get clever.”

We drive in to Horselunges, and I'm thinking, “Why am I doing this for fucking Dave Edmunds?” I'm introduced to this twenty-stone gardener named Ron or something and told that he'll be looking after me. “Peter'll be down in a minute,” he says. “Don't go snoopin' around.” I sit there for an hour, and Ron comes back in: “He's not ready yet.” Another hour and a half goes by, and I'm trying to stay cool.

Finally, Peter comes down in this Japanese toga, three hundred pounds of hungry and clearly a very unhappy man. He sits down and pulls out this big brown bottle of cocaine. He says, “'Ello, Mr. Punk Rock. You fink you're a bit of a clever boy, doncha?” I say, “I think I'm pretty smart, but only like you're smart, Peter.”

He says, “I 'ear from Phil Carson that you're a bit of a ducker and a diver.” I try to make him laugh, but it's very hard to make someone laugh who's coked out of his brains.

He says, “We wanna sign Rockpile.” I say, “That's good, but, unfortunately, Columbia is never going to let Nick Lowe out of his contract.” The pitch to Peter goes on for two hours and is basically this: “I'm young and I'm shaking—I'm you twenty years ago.” I say, “You're my hero. I want to build up a label as cool as Swan Song. Dave Edmunds is a wanker, and you don't need the grief, so why don't you leave him to me and get on with running your empire?”

He says, “You fink we're all dinosaurs.” I say, “Not at all. Jimmy and Robert came down to see the Damned twice, and that's nothing but respect. I'm just a Mod from Eastcote, and I've got a little record label, and this is my big chance.” I say, “If we don't do this, there won't be a Rockpile, and you'll get stuck with Dave.” I lay it on with a trowel, and much to my surprise, he says, “Alright. I like you. I'll let you do it.”

We shook hands, and I walked out. I could have leaped over that fucking moat.

UNITY MacLEAN It all starts at the top. You had all these minions down below who loved being aggressive and were being told, “Yes, go ahead, I'm paying you. Do your worst.”

ED BICKNELL (former manager of Dire Straits) If, as the driver of the thing, you are a complete shitbrain, it's likely that everyone else is going to be a complete shitbrain. And when you lose the plot, there's an awful lot of people who want to lose the plot with you. Because it's fun and glamorous and all that.

AUBREY POWELL (designer of Zeppelin album covers) I'd go 'round to Swan Song, and Richard would greet me by saying, “What the fuck do you want, you cunt?” I'd say, “I've just come to have a meeting with Robert.” And he'd say, “What d'you wanna fuckin' talk to that long-haired git for?” It was just this powerhouse of madness.

JAKE RIVIERA I don't know where they dug these people up. They were like rock apes. There was a guy called Magnet, and every other syllable he had to swear: it would be “Los-fuckin'-Angeles,” in a Brummie accent. I once asked him if I could put some guests on Nick Lowe's list. He said, “I'll 'ave to check with the fuckin' office.” I got a bit shirty, and he said, “Don't fuckin' get smart with me, ya fucker.” I'm figuring, “I really don't need this shit.” Dave knew he was trapped in that thing, but he loved Robert Plant telling him how fantastic he was.

DENNIS SHEEHAN (assistant to Robert Plant on 1977 U.S. tour) Johnny Bindon used to hang out with Cole at the World's End, opposite Swan Song. Maybe Richard felt Peter needed somebody like Bindon, but to me, it was like the blind leading the blind.

UNITY MacLEAN Bindon was born to a big Irish family in Fulham and I think was pretty badly treated as a child. Then he got these bit parts in movies and did all right for himself. Richard was friendly with Lionel Bart, who knew Bindon. A load of wide boys [hustlers].

Peter would have said, “We need tough guys like you.” And Bindon could be very sociable. He was a great raconteur and moved in some pretty smooth circles. He could chat with Peter about Princess Margaret, and Peter would probably hang on his every word. I don't think they realized they were unleashing the creature from hell. He was sitting in the office one day with that slagette Vicky Hodge, and she had a dress on that was all poppers, and he ripped it off her in front of everybody. Everybody else seemed to see the fun side of Johnny Bindon, but I never did.

Peter with John “Biffo” Bindon, Edgewater Inn, Seattle, July 1977. (Richard Cole Collection)

BENJI LeFEVRE (Zeppelin sound technician, 1973–1980) It was truly frightening whenever Biffo came into the office or when we went to the Water Rat with him. But up to a point, it was also extraordinarily funny.

ALAN CALLAN I believe there was a huge turning point with Zeppelin when they got their first death threat. I think that changes the entire environment around you. The justification for having someone like Bindon around was that if things got bad, he would take a bullet for you. Richard was tough, but John could look you in the eye and intimidate you. You knew you would really have to hurt him badly to stop him coming after you.

MARILYN COLE Peter was desperately lonely—he had all the money in the world, but no woman in his life—and along comes Biffo. Personally, I loved Biffo. He was hugely bright and very entertaining, quite apart from the fact that he'd whip out his old John Thomas. He would recite Shakespeare in the middle of a pub and do it beautifully. But he was also very unpleasant and dangerous, if not actually psychopathic. You didn't really want him in your home.

Biffo sort of moved in and elbowed Richard out of the way, and Richard allowed it to happen. If Richard was ever sober enough to think about it, he was probably quite put out.

CYNTHIA SACH (secretary at Swan Song in the U.K., 1977–1981) Bindon was always trying to intimidate people. He'd go into the Water Rat and get his willy out. It was the most hideous willy I'd ever seen, thin and pale and vile. And he'd wave it around and hang beer mugs off it.

PAMELA DES BARRES (L.A. groupie and girlfriend of Page's in the late '60s) They just hired the wrong people, like the Stones hiring the Hell's Angels at Altamont. It wasn't so much the band. It had a lot to do with Jimmy not wanting anyone to know anything about the band, so it was doubly insulated in that way.

BP FALLON Bindon was bad news. That's not what this is meant to be about: people going around beating people up. Everyone knew about him. Very charming and very funny and all of that, but at what price? You might as well have a tarantula in your handbag.