23

Polar Opposites

Powerless the fabled sat, too smug to lift a hand / Towards the foe that threatened from the deep …

—Robert Plant, lyric from “Carouselambra” (In Through the Out Door)

JOHN PAUL JONES Robert was wondering whether it was worth it after the grief. I suppose we were questioning things.

ROBERT PLANT Led Zeppelin had gone through two or three really big changes. The whole beauty and lightness of 1970 had turned into neurosis. It was like a very big tackle from Vinnie Jones—bang! And then you had to pick yourself up.

My own condition and my family had suffered quite a bit. I'd lost my son, and at that time I found that the excesses surrounding the group were such that nobody knew where anyone was. The 1977 tour ended because I lost my boy, but it had also ended before it ended, really. It was just a mess. Where was the actual axis of all this stuff? Who do I go to if it's really bad for me? There was nobody. Everybody was insular, developing their own worlds.

DENNIS SHEEHAN (assitant to Robert Plant on 1977 U.S. tour) I think I saw Robert about five or six times in the months after Karac died. I went up to Jennings Farm and also to Wales. At that point, he had no inclination to ever want to do anything again.

ROBERT PLANT When I came back to my family, I received a lot of support from Bonzo, but I went through the mill because the media turned on the whole thing and made it even worse. I had to look after my family, and at that time—as we regrouped—I applied to take a job at a teacher training college in Forest Row in Sussex, the Rudolf Steiner Centre. I wanted to get out of it.

I was heading off up this path where I couldn't hack it anymore because I didn't know where anybody was. And then Bonzo came over and worked on me a few times with a bottle of gin and was very funny. Because he and I had a history that went so far back, it was wonderful. He said, “Come on, we're all going to go down to Clearwell Castle to try and do some writing.”

PETER GRANT Robert kept saying he'd do it, and then he'd back down. But Bonzo was a tower of strength. We had a meeting in the Royal Garden Hotel, and they started talking about Bad Company and Maggie and all that, with their Swan Song hats on, and I said, “What the fuck are you talking about? You should worry about your own careers!”

JOHN PAUL JONES Getting back together at Clearwell was a bit odd. I didn't really feel comfortable. I remember asking, “Why are we doing this?'' We were not in good shape, mentally or health-wise. Perhaps nobody was strong enough to stop it—including our manager, who wasn't that well himself.

JIMMY PAGE Someone approached me saying that Abba had this studio called Polar and were desperate to get an international band to play in there. Plus, they'd give us three weeks' studio time for free. We went over there, and it was bitterly cold and snowing, and we were commuting from the hotel to the studio. We did have quite a few numbers that had been routined, and we rehearsed those in north London, but things still came up in the studio.

JOHN PAUL JONES Robert and I were getting a bit closer—and probably splitting from the other two, in a way. We were always to be found over a pint somewhere, thinking, “What are we doing?” And that went into In Through the Out Door. Basically, we wrote the album, just the two of us. I'd got a brand-new instrument as well, the Yamaha GX1—“the Dream Machine”—which was inspiring me. And suddenly, there was no one else to play with. Bonzo turned up next, and we had it all worked out by the time Jim turned up.

JIMMY PAGE Jonesy hadn't really come up with anything on Presence, and he was to be encouraged. The Dream Machine really inspired him to come up with some things.

BENJI LeFEVRE (Zeppelin sound technician) On the fourth floor of the Sheraton we had four suites, one in each corner for each member of the group. Then there was me, Rex King, and Andy Leadbetter, who looked after the Dream Machine. The band decided they were going to work Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday and go home at weekends. They kept the suites on over the weekend, so me and Rex had the run of the hotel, with birds in every suite.

We'd waltz over to Atlantic's office in Stockholm and say, “Oh, we need another five grand for expenses.” It was never a problem, but at the end we had to try and account for tens of thousands of pounds! I went to Robert and said, “Look, we've been scoring for Jimmy and Bonzo and this and that. Joan's going to be saying, ‘Where's all the money gone?” He said, “Oh, don't worry, just write up something for fish and chips.” So I got a piece of paper and wrote, “Giggle and Spend Ltd: Fish and Chips, $25,000.” And Robert signed it.

ROBERT PLANT Jonesy and I, who had never really gravitated toward each other at all, started to get on well. It was kind of odd, but it gave the whole thing a different feel: things like “All My Love” and “I'm Gonna Crawl.” We weren't going to make another “Communication Breakdown,” but I thought “In the Evening” was really good. Parts of “Carouselambra” were really good, especially the darker minor dirges that Pagey developed. I rue it now because the lyrics on “Carouselambra” were about that environment and that situation. The whole story of Led Zeppelin in its later years is in that song, and I can't even hear the words.

BENJI LeFEVRE The engineer, Leif Mases, was a great guy. Initially, I felt he was a bit out of his depth, because he was so used to being part of the Abba machine. Polar was a fantastic facility, but the fire alarm was a bit dodgy. One time Bonzo was laying down a groove, and the alarm went off, and all these firemen burst in. He looked up at them and just carried on playing.

Jonesy had this fantastic new toy, and because this machine made fantastic noises, Robert suddenly became interested again and thought it might be a new departure. It was like, “Is this where we can turn things around a bit and move forward in a different direction?” Which is something he's always looked at, right through his solo career. So, creatively, there was a shift in the balance of power, and I think that gave Jonesy the confidence to do what he's done since.

Whether it was better or not, who knows; it was certainly different. I'm guessing Jimmy tried to re-exert his influence over it and sucked Leif in, because Leif ended up working for him at Sol Studios.

SAM AIZER (artist relations at Swan Song in the U.S.) They could have had a number one with “All My Love” if they had released it as a single, because it was the most-played record on the radio.

ROSS HALFIN (photographer and friend of Page's) I would say that Jimmy is embarrassed by In Through the Out Door. He hated “All My Love,” but because it was about Karac, he couldn't criticize it.

JIMMY PAGE It's a bit scary because it looks like I'm moving into the '80s, and we all know what happened in the '80s—absolutely horrendous. Maybe we would have come to our senses, sooner or later.

ROBERT PLANT I love “Wearing and Tearing,” which Page and I wrote together. We were so pissed off with the whole punk thing saying, “What do those rich bastards know?” First of all, we knew that we didn't have that much dough. Secondly, we knew more about psychobilly and the psychotic side of Hasil Adkins than they did.

RICHARD COLE We'd leave Stockholm, and something completely different would have turned up in the studio on a Monday. Jimmy may have had the same Neve desk at home, but all I know is when the stuff came back after the weekend, you wouldn't even recognize it.

AUBREY POWELL (designer of In Through the Out Door cover) Peter said to me, “We could put the album in a brown paper bag, and it would fucking sell.” I said, “Peter, what a great idea.” Atlantic didn't want the aggravation, but Peter said, “We're fucking doin' it.” In Through the Out Door ended up having six different covers.

MITCHELL FOX (Swan Song, U.S.) Steve [Weiss], Shelley [Kaye], and I went over to Atlantic and played the record to Ahmet and Jerry Greenberg. I was certainly aware that delivering a new Zeppelin record to Atlantic and WEA was a very big thing. And when I pushed play and “In the Evening” came off that tape machine, you just saw everybody light up. It went on to debut at No. 1, with eight other catalogue albums entering the Top 100. That meant that Zeppelin owned 10 percent of the chart.

ROBERT PLANT Nineteen seventy-nine dawned with the album done. There was something going on, and it was lifting again. We decided that we could work, and we should start all over again. It was agreed that we should play in England.

SAM AIZER I was in England when Logan Plant was born, and that was a very joyous day. Benji came down, and Peter was there telling jokes.

DAVE LEWIS (editor of Zeppelin fanzine Tight but Loose) Peter told me, “Look, if we're coming back, we need to do the biggest fucking thing there is. If it's Knebworth, then we do Knebworth.” That year I think the Who did the Hammersmith Odeon and the Rainbow, and Zeppelin could have easily done that. Instead of doing two Knebworths, they'd have been better off doing one Knebworth and then a week at the Rainbow. They'd have got their audience back.

JACK CALMES (Showco lighting and sound) After Peter and I did the Knebworth deal, he invited me out to Horselunges. I think he really wanted to have a friendly relationship. We'd sit there and talk for a while, and then he'd drift off and disappear. Then he finally just drifted off, and I took the car back the next morning.

RICHARD COLE I'd flown over to Copenhagen for the Knebworth warm-ups. I had their money for drugs, because Jimmy and Bonzo and I needed the fucking gear. My dealer was in the next room in the hotel, and when I was pulled about it in this big meeting that Robert called, Jimmy said he knew nothing about it. Bonzo said, “Don't be so fucking stupid. If there's no gear, there's no show!” And Peter knew what was going on: he sort of winked at me as if to say, “Don't worry about it.”

PHIL CARLO (roadie for Bad Company) If you didn't know that Bonzo was dabbling, you'd never have noticed. With Jimmy, it was quite obvious. Bonzo was a big, robust, rambunctious person, whereas Jimmy was always nodding off.

ROBERT PLANT When you love somebody, you're prepared to take any amount of excuses. So long as it doesn't really do that much damage, you tend to put up with it.

SAM AIZER Robert is watching it right in front of him and praying to God nothing crazy will happen. He's already taken a hit-and-a-half losing his boy, and he's coming back from that, and now he sees Bonzo out of control. He must have thought, “What the hell is going on here?”

JOHN PAUL JONES Robert didn't want to do Knebworth, and I could understand why. But we really did want to do it, and we thought he'd enjoy it if he did it … if we could just get him back out there.

GARY CARNES (lighting technician at Knebworth shows) It was on the 1979 shows that I actually got close to the band, because we rehearsed for Knebworth for a whole month. Page used to walk into rehearsals with this big box of Popsicles and give us each one. We would say to each other, “Wow, he used to spit on us, and now he's handing out Popsicles.”

They booked themselves into these shows in Denmark under a different name, some off-the-wall name like Jimmy and the Blackheads. There we were, loading all this gear into the venue for a band nobody had heard of. People were coming up to me and saying, “Who is this band?” And everybody kept their mouth shut because they didn't want the wrath of Peter Grant on their heads.

The band members were nervous and scared because they hadn't played in front of anyone for a long, long time. On the first show, there were only about sixty to eighty people there, and they all went nuts. Of course, the next night, in Copenhagen, was out of control.

ROBERT PLANT During the preparations for Knebworth we were really very nervous, but the great thing that happened was that it did bring us back together.

TOM FRY (assistant to promoter Freddy Bannister on Zeppelin's Knebworth shows) Freddy advertised in the newspapers for somebody to help him with the Knebworth Festival. A flatmate of mine got the job, and they needed somebody else as well. So we went along, and our initial job in those predigital times was to send tickets in the stamp-addressed envelopes.

Peter Grant was this big ogre at the end of the phone somewhere. I remember one day picking up the phone and saying, “Hold on a minute,” and flinging this phone down and coming back to it three minutes later, saying, “Sorry, I forgot you.” “It's Peter Grant.” “Oh, I'm sorry.” He said, “Doesn't matter at all.” I do think that with many of these monsters, it's actually the people who surround them who create a lot of the fear.

AUBREY POWELL For the program photos, I arranged for a stripper to try and lighten the mood a little. Bonzo turned up and looked dreadful: he was bloated and fat and sweating and belching, with a bottle of Pepto-Bismol in his pocket.

GARY CARNES The night before Knebworth, Mick Hinton had bought an ounce of blow and was chopping some of it up on the end of a wooden bench. Bonham came in without Mick seeing him and went “Shhh” to us. He jumped on one end of the bench, so all the coke went flying up all over the room.

BENJI LeFEVRE For the sound check, Bonzo asked Jason to get behind the drums and came to the mix tower to hear what it sounded like. He said to me, “Fucking hell, man, I've never heard it like this. It sounds amazing.” That's the problem for most musicians: they never really get to hear themselves.

ROBERT PLANT As we got to Knebworth, it was dumbfounding to see that people had bought 220,000 tickets for the first night. Freddy, who'd booked me in the Town Hall in Stourbridge for eight quid, was going, “I say, Robert, I think you've made a bit of a killing here.” In some ways, it was a shambles, and in other ways I think I was a bit embarrassed about how big it was.

JIMMY PAGE I didn't feel very happy at all, and I wasn't well on the second weekend. For me, it was that thing of getting families in position. My parents had split up, and they both had different families, so one was coming one weekend and the other the next. It was fantastic, though, the reality of it: coming in by helicopter, you could see this huge sea of people. It was astonishing.

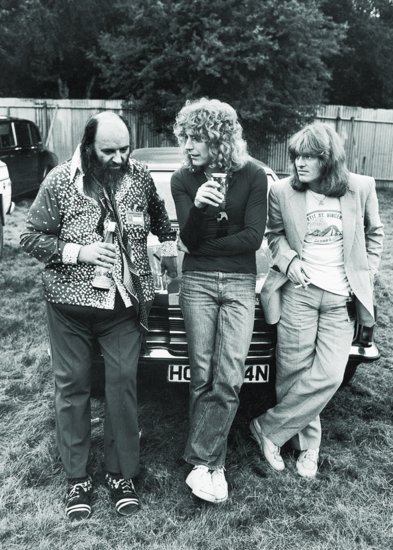

Grant with Plant and Jones in the VIP enclosure at Knebworth, August 4, 1979. (Ian Cook/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images)

HELEN GRANT (daughter of Peter Grant) Dad had a VIP enclosure and a liggers' enclosure. Anybody that looked a bit suspect, it was like, “Oh, get 'er in the liggers' tent.”

TONY MANDICH (artist relations manager in Atlantic's L.A. office) They said, “Don't compare this to L.A. backstage.” There was nobody there. It was family members and a few kids running around, and that was it.

ROSS HALFIN I went with [photographer] Chalkie Davies, and I remember we climbed the scaffolding by the stage and found ourselves on the video ramp. And this big security guy threatened us, so we said, “Oh, Peter Grant said we could come up here,” so we were able to stay.

There was a real malevolence about things backstage, whereas previously you'd been able to wander around and take pictures of anyone. That was the first time I'd encountered that kind of heaviness. We eventually ran into BP Fallon, who was out of his brains on speed, and he marched us through the security into the dressing room.

Zeppelin were totally personable. They posed for us and everything. I was shocked, because I expected them to be a bunch of cunts. But all the people around them were cunts, absolutely fucking horrible. You couldn't work out whether it came from the band or from Grant. My experience with bands is that it always comes from the artist, no matter how much they dress it up. They want that, even if they don't admit it.

DEBBIE BONHAM (sister of John Bonham) John had come 'round to the house and said they were going to do this big show. I said, “Oh fantastic, I can't wait to see it.” He said, “You know what, I don't think you should come to this one, because it's outdoors, and I don't really want family there. We've got some indoor shows coming up, and you can come to them.” I just looked at him and said, “No, I'm coming.” I remember thinking, funnily enough, that if I didn't see him then, I wouldn't see him play again.

I got there, and I tried to get in backstage. I told the guy I was John Bonham's sister and he said, “Oh yeah? Where's your pass?” And then it got quite frantic because I didn't let it go, and he threw me against the fence. At that point, Richard Cole came out and said, “It's Bonzo's sister! Let her in!” John came round the corner and he just saw me, and he ran and picked me up in the air, and I burst into tears. And he hugged me and held me for ages, and then he put me down and said, “What did I say to you about not coming?”

TOM FRY The interesting thing to a young punk rocker was that Led Zeppelin were on the banned list. I seem to remember they were all in white, with white light hitting the stage, and we were a long way back because we'd been in the enclosure, but then they came on, and they were terribly impressive, even to someone who was programmed to loathe them. It was an extraordinarily powerful, professional, compelling, can't-take-your-eyes-off-it show. My feeling was that they played too long, and the show got sort of diluted a bit. But the first half hour was just sensationally good.

JOHN PAUL JONES The biggest lie ever told about Zeppelin is the whole dinosaur thing—that we were musically bloated or pretentious. We were never pretentious.

ROSS HALFIN I didn't see Led Zeppelin as dinosaurs at that point. It was Plant onstage who was always making snide remarks, like, “Are we gonna do the dinosaur rock?” He kept making all these sorts of digs at the punk thing, which is what he always does when it's something he's jealous of. I don't think they were even disliked, particularly, 'cause I've got pictures of Mick Jones, Chrissie Hynde, and Paul Cook backstage at Knebworth—they were all there.

But Zeppelin had, in a sense, become elitist and lost touch with their audience, whereas Pink Floyd never were in touch with their audience but were accepted nonetheless. That was one of the sad things about Zeppelin, that they'd become this sort of steamrolling giant. I don't know if they would even have survived the '80s.

PETER GRANT Do you remember at Knebworth, [Robert] sang the wrong words in “Stairway”? Unforgivable, really. He was in a difficult frame of mind. And then there was all that speech onstage: “We're never going to Texas anymore … but we will go to Manchester,” and all that, and as he's saying it he's eyeing me out at the side of the stage.

ROBERT PLANT I watched Knebworth on DVD and thought, “That was a shit gig, and I know how good we had been and how good we could be, and we were so nervous.” And yet within it all, my old pal Bonzo was right down in a pocket. I'd thought he was speeding up, but I must have been so nervous myself that every single blemish or twist that was a little bit away from what I expected was making me hyper.

If you listen to “Achilles Last Stand”—from all that had gone on and all that had gone wrong—it was absolutely spectacular. At the end, I don't know whether I was breathing a sigh of relief because we'd got to the end of the show in one piece without anything going wrong, or because we'd actually bought some more time to keep going.

UNITY MacLEAN (manager of Swan Song office in the U.K.) On the day of the second gig, Peter decided he wanted more money. So Freddy's running around having kittens, shouting, “Where's Peter? Where's Peter?” Well, Peter had gone to ground. He'd presented his fait accompli: “I want more money, or the boys aren't going onstage.”

TOM FRY The problems happened between the two gigs that were on consecutive Saturdays. Zeppelin were on a cut of the take and were asking to be paid in cash.

Freddy wasn't thrilled about this arrangement. It took place in his house at night with the curtains closed, because I remember coming in the following morning and him being very shaken up. Zeppelin's management had arrived, and Freddy was up there, and they had £300,000 in cash. It was 1979, so it was a hell of a lot of money.

Doubt was expressed by Zeppelin's management company about whether this did legitimately fulfill the percentage arrangement or whatever it was of the total box office. Freddy always gave the impression that he was scrupulously honest and said, “How dare he doubt it!” They said, “Well, we've flown a helicopter over the site on the first week, and we've counted 120,000 people, and you're saying it's only 95,000 or whatever the figures were.” Freddy said, “Well, I'm not 100 percent sure.”

They then began to make threats and said they wanted to take control of the box office for the rest of the second show. The impression I got was that Freddy was initially quite resistant to this, and they then pointed out gently that several people had died on their American tour in suspicious circumstances, and they wished to remind him that they did have friends on the East Coast of America. Freddy said, “My lawyer is in the room, and you're saying this! What on earth are you suggesting?” He was clearly was very shaken and deeply offended.

On the Tuesday, I think, we came in, and Freddy was in this fretful state about this meeting. He said, “They're basically going to take control of the box office, and we've got to start to counsel some grievances because this is going to cost us a fortune.”

By the Wednesday or Thursday of that week, Freddy had given up the ghost—like, “If they want the tickets, they can have the fucking tickets.” He asked me to take them up to the site for him. He said, “This is John.” John was about six foot six and an SAS [Special Air Service] sort of bloke, who said, “I'll be driving you up, and I'll be accompanying you for this mission.” I was nineteen or twenty years old and said, “Great”—me and my kind of Rug Rat impersonation of Mick Jones's haircut, with light green trousers and winkle pickers.

We put what must have been about £30,000 to £40,000 worth of tickets into the back of this car and drove up to the site, where I'd been told to go up to the Zeppelin management tent. This guy came out who'd walked straight off the set of Mean Streets. It was as cartoony as that. The crowds parted, and this small guy in tinted shades—about five foot three, with nicely parted hair and beige slacks—said, “Tom, is it? Nice to be doin' bidness with you. I believe you have a consignment for us.” I said, “This is John.” He said, “Yeah, this is Billy.” So he had one, too.

The guy said, “Shall we go somewhere?” So we brought these tickets out of the car. We went to a café and sat down in a trailer, and I lifted out the tickets and put them on the table. Billy was assigned to count them, and he picked up a book of tickets—“One, two, three, four …” I said, “Can we accept that there are five hundred in each book?” He said, “Tom, you're a man of honor. Of course we will accept that.

The interesting thing is that the mob had always tended to be involved with mediocre artists like Tommy James or Lloyd Price and Larry Williams, but somehow they'd got their claws into Led Zeppelin. You're really gearing up when you're dealing with these guys. I think Peter was getting out of his depth. It was a bit of a date with the devil.

UNITY MacLEAN My husband reckons Commander Cody and Todd Rundgren never got paid. As for the New Barbarians, they couldn't get Keith Richards out of the limo because he was so out of it. And then when they got him onstage, they couldn't get him off it.

TOM FRY The Barbarians wouldn't come on and sat in their dressing room. Word got out that they'd been told by Peter not to go on until they were paid. I think in the end it must have been Peter who paid them, because Freddy said, “I'm not paying.”

BENJI LeFEVRE There was a huge political thing going down with the New Barbarians. It was like, “We are Led Zeppelin, and you may play on our bill.” Jimmy never even came out to say hello to Keith and Ronnie.

TOM FRY I went back the following week to tie up loose ends, and Freddy had had enough and said, “God, I thought it was difficult working with the Stones until I came up against this lot.” Freddy rarely promoted stuff after that. It was a thoroughly unpleasant experience for him.

CAROLINE BOUCHER (writer for Disc and Music Echo) Freddy's house was a huge former embassy. He bought it for not much and spent a fortune on it. He was going to make a shed load of money on this building, and the decorator was in there putting the last gold leaf touches to something when a team of people burst through the door, ran to the top of the house, and spray-painted it black from top to bottom and ran out again. Everybody went, “Oh, Peter Grant.”

• • •

ALAN CALLAN (president of Swan Song in the U.K., 1977–1980) I remember thinking, “I'm working too hard and taking too many drugs, and so is everybody else. I'm not finding the fulfillment in the nature of the artists that I'd like to achieve.” There were too many fights going on, and there were too many drugs around, and what they really needed to do was figure out whether they could rebuild themselves as a band. Until they did that, it was always going to be, “Well, call me tomorrow.”

I said to Peter, “I don't think this is going to work anymore.” I don't think he even heard me. Some months later, I bumped into Storm Thorgesen, and he said, “Where've you been?” And I said, “Oh, just around. Why?” He said, “Well, I was at Swan Song last week, and Peter wants to know why you haven't been in the office.”

RICHARD COLE Ray Washburn sent me 'round to the office to get Alan Callan's company car. That was how we found out Alan had gone.

SAM AIZER Boy, did Alan get eaten up alive. Abe Hoch got eaten up alive. There was no chance. Would Bad Company have been as huge if they'd been on Columbia? Yes. They had great songs, a great band, they had Rodgers, who was the best singer going. But none of the other bands happened.

Look, Led Zeppelin was a huge band: this was a full-time operation all the time. They would sign bands, but it was just a vanity thing. And yet it was the most powerful label at Atlantic. If we blinked, they said, “What do you need?” We want a full page, they give you a full page. But the other bands really didn't have a chance.

I'm sure if they'd signed Roy Harper that Robert would have been involved. But it was hard enough just to keep them physically together as people in England. Think about trying to schedule tours and merchandising and this and that. Who's going to do that? Not Peter. Peter got iller and iller and iller.

I left in the middle of 1980. I wrote them all letters, saying, “I've been offered a job on Wall Street by my brother.” I said, “If you guys are going to work, I'll stay. If you're going to sign bands, I'll stay.” I don't think anyone even read the letter.

DON MURFET (head of security for Zeppelin in the late '70s) Paul McCartney's company, MPL Communications, hired us to provide men to handle the overall security at a very prestigious award ceremony that the Guinness Book of Records was holding at Les Ambassadeurs off Park Lane. I was just checking out the members of Pink Floyd when one of my men said there was a call for me upstairs. At the reception desk, I found out the call was from Ray Washburn—and it wasn't the best of news. They'd just found one of Jimmy's guests dead at Plumpton Place.

I arrived at the same time as the police. Obviously, that was because they'd been called out by the ambulance crew—which is standard procedure. Their presence meant that I couldn't “clear up” the way I'd have liked to. All I could do was confine their investigations to the guest room where the guy—whose name I later found out was Richard Churchill-Hale—had popped his clogs.

KEITH ALTHAM (writer for NME and other publications) Phil Carson and Ahmet Ertegun drove down to Horselunges for Warren's fourteenth birthday party. Ahmet asked Phil what he should buy for Warren, and Phil said he thought he was into archery. So Ahmet bought Warren a crossbow. Eventually they get to the house, and it transpires that Peter has been winched out of his bedroom for the first time in two years. Ahmet tells Peter he's bought Warren a crossbow, and Peter goes, “That's really nice of you, Ahmet, but you won't spoil my surprise, will you?” Ahmet asks what the surprise is. “I've got 'im an 'arley Davidson.”

AUBREY POWELL Peter asked me to film this helicopter that was bringing in the bike, which Barry Sheene had given him. But then the helicopter came over the house with a chain hanging from it and no bike on the end.

You could feel the shudder that went 'round everybody. Richard and Ray were there and, I think, Bindon. The helicopter landed on the front lawn at Horselunges, and you could see Peter's face was dark. He sent Warren away.

The pilot got out and came into the house: “I'm terribly sorry, Mr. Grant, but the chain broke, and the bike is in a field about three miles away.” The guy said he would have to sort it out with the insurance company. Peter said, “Forget that, you're not leaving here. I want you to call your boss and have him bring me £5000 in cash right now for the bike.” The guy said he couldn't leave the helicopter, so Peter told Richard to go and dismantle it.

The pilot was freaking out. He called his boss and then came back in and said it was all settled. Peter sat there and looked at him and said, “What does it feel like to be called a fucking liar?” You could see the pilot was sweating and very nervous. Peter said, “Here's the recording of your conversation with your boss”—because by this time he was so paranoid, he would record every phone conversation he had, even conversations with Ahmet. The guy had told the pilot to get the fuck out of there.

Peter said, “You go to your boss and say if I don't get five thousand pounds this afternoon, the helicopter doesn't leave.” He then turned around to me and said, “Call Barry Sheene and get another bike.” I was like, “I don't know Barry Sheene.” Suddenly, I was part of the whole equation, phoning Australia, trying to get hold of Barry Sheene! I didn't leave till four in the morning, and Peter was still raving and groaning.

BENJI LEFEVRE Steve Weiss came over for some apparently unbelievably important meeting, and G just wouldn't come up to London to talk to him. Limos were sent. Helicopters were sent. Eventually I was asked to go and talk to him, and I got there, and I asked Ray Washburn where he was. He said, “He's out by the moat.” I found G sitting on a wooden bench with a shotgun, going, “I know that fuckin' pike's in there, Benj … I'm gonna 'ave him.”

I said, “What about Steve Weiss?” He said, “Fuck Weiss, I've gotta get this pike.” Ray said he'd been there for three days.