25

Staggering from the Blast

I think I will go to Kashmir one day, when some great change hits me and I have to really go away and think about my future as a man, rather than a prancing boy.

—Robert Plant, July 1977

ROBERT PLANT When Bonzo went, I was thirty-two. Washed up and finished. That's what I thought.

BENJI LeFEVRE (Zeppelin sound technician) I think all three of the guys realized that it could not be perpetuated. We all went to Jersey, the three of them and Peter and the crew. It was pretty clear that we were there because John wasn't—and that we were all going to go our separate ways.

JIMMY PAGE After having had all those years of having this total free spirit to everything, to have to sort of clamp it down and compromise at that time of the passing of John didn't seem at all palatable.

PHIL CARLO (road manager on Tour over Europe) G said to me in the months after Bonzo's death, “Phil, you would not believe how many messages were left on the answer machine within days, asking if they were looking for another drummer.” A lot of people went down in my estimation. G said, “I can't fucking believe any of them. When are they going to get the message? This is not about money or anything. That's it. That's the end of it.”

DEBBIE BONHAM (sister of John Bonham) The realization was that they weren't going to do Led Zeppelin anymore. Which I think we all felt great relief about.

DESIREE KIRKE (ex-wife of Simon Kirke) After Bonzo went, the relationship between Robert and Peter got really strained. Everything got really strained.

DAVE LEWIS (editor of Tight But Loose) Jimmy was in a dreadful state. Peter was in a dreadful state. Robert was a changed man, without a doubt, and you couldn't mention Led Zeppelin to him. Led Zeppelin stock fell dramatically. It was gone. In that early 1980–1982 period, it wasn't a very cool thing to be a Zeppelin fan anymore.

JOHN PAUL JONES I was supposed to be managed by Peter still, but during those first couple of years, it was hard to get hold of him. He wasn't coping very well at all. It was a frustrating time. [Coda] seemed to close the book on that chapter. We had a bit of a job finding enough tracks.

PHIL CARSON (head of Atlantic in Europe) There was a complete void when Zeppelin stopped. Jimmy still wanted to make music, and so did Robert. But neither of them wanted to play Zeppelin music. It took three records, I think, before Robert would approach Zeppelin tunes again.

ROBERT PLANT I cut my hair off, and I never played or listened to a Zeppelin record for two years.

AUBREY POWELL (designer of Zeppelin albums and friend of Plant's) When Robert went out for the first time after Zeppelin, I think he felt the first taste of freedom in a very long time. He was able to express himself without his old partner. And Jimmy was hurt by it because Robert wouldn't go back and re-form Led Zeppelin.

BENJI LeFEVRE I was living in the barn across from the house above Robert's snooker room. With the Queen's Head football team, we would go away annually on these fucking bonkers trips. We would arrange a match on a Sunday morning with a local football club in Penrith or wherever.

The deal was that they should provide us with somewhere to pitch Robert's Moroccan tent—which slept twenty-eight people feet to the pole—and we would do an impromptu gig at the local social club on the Saturday night. It happened about three or four years on the trot. There were these local musicians that had already been kicking about: Andy Sylvester, Robbie Blunt, Wayne the Gasman. We were talking about music, and I said, “Maybe I could put a little studio together for you, and we can have some fun.” Andy and Robbie came up and pratted around. We actually pressed up a version of “Little Sister.”

That became the original Honeydrippers. We did maybe fifteen or twenty gigs over two or three months, nearly always at weekends because a couple of the guys had regular jobs. Robert's stipulation was that everything had to be north of Watford. I contacted all the promoters and said that if they used Robert's name in the advertising, we wouldn't show up for the gig.

ROY WILLIAMS (live engineer for Plant) Robert and I used to get together in the Bull and Bladder in Brierley Hill, and that sort of developed into the Honeydrippers thing. I ended up booking all the Honeydrippers' club dates, on the basis that nobody could mention his name, other than inside the club itself.

Robbie Blunt was in the band. Peter Grant was sitting in the background, though he wasn't hands-on managing him, so we had that Zeppelin machinery of sourcing anything in the press. I think the clubs were more than pleased that they got what they got.

ROBBIE BLUNT (Plant's guitarist post-Zeppelin) Benji put together a little studio at Robert's farm, with a little four-track TEAC, and we just started playing. Andy Sylvester and I did a couple of recordings, and then it went from there. This thing had already started without me, so I just did what I was told. Robert had got all his old tunes that he'd loved and had never had a chance to do. I suppose it was just to play for the pleasure of it and not forget why we'd all started doing this.

ROY WILLIAMS I even booked them into the Keele University ball. The social secretary said, “Who the hell are the Honeydrippers?” And I said, “I can't tell you, just trust me on this one.” I don't think there was anybody in the room for the first four numbers.

ROBBIE BLUNT Obviously, Robert couldn't just keep doing that. He'd put his toe back in the water, but he said to me, “I'm getting a bit fed up with this.” At the last gig in Birmingham, he said he was going to tell the chaps he wanted to jack it in. So I said, “Well, I'm not going to stay with it, either.”

ROBERT PLANT The idea that if all else fails, you can go back—that was never in the equation. Led Zeppelin had been incredibly successful, we'd had a lot of fun, spent a lot of money, been in a lot of limousines, half of Peru had already been inhaled, but there was no way to go back to where I'd been before. Best to just do whatever I feel like doing.

ROBBIE BLUNT I said, “Look, just give me a chance to write some stuff with you. That's all I ask.” I guess I bullshitted myself up. I don't think I realized the consequences of my actions till later. It wasn't like we had a board meeting to specify what we were going to do; it was just, “Let's play and see what happens organically.”

ROBERT PLANT It was so uncomfortable to begin with that I wasn't sure I could handle it. I started getting so many flashbacks of the night Page and I wrote bits of “Stairway to Heaven” or of doing the lyrics of “Trampled Under Foot” or whatever. I found myself getting all these great swirls out of the mist, and at first I couldn't cope. But I got used to it. And once I'd done it once, I realized I could do it a million times.

ROSS HALFIN (photographer and friend of Page's) I remember photographing Robert at Shepperton, and Robbie Blunt was there. I said, “Can we get you with a guitar, Robbie?” And Plant goes, “Why can't he have a fishing rod?” There were all these jibes at Page that I didn't realize at the time were jibes.

BENJI LEFEVRE It evolved organically through the Honeydrippers thing. It wasn't forced or pushed, it just started to happen. Robert asked me to be his manager, and I said I really couldn't do that.

It got to the point where we decided to do some real rehearsing. Robbie knew this really good bass player, Paul Martinez, and we found a keyboard player called Jezz Woodroffe, whose dad had owned a music shop in Birmingham. Andy Sylvester was very wary of the whole thing.

We ended up at Rockfield studios, in the second house by the river, trying to write some songs. Cozy Powell came down. It was all pretty mad. Robert was starting to put Robert-type pressure on things, but Robbie was okay with it. It all was going very nicely—we're a brotherhood and all that—until it came to the publishing. It had been a complete cooperative, and then Phil Carson and Peter and Joan came in on it. I'm sure Robert was advised this, that, and the other.

PETER GRANT In the early '80s, I was disappointed and hurt by [Benji's] plan to become Robert's manager, which all went wrong in the end. I used to phone up, and I'd never get a return call or any communication…. Robert and I did have a bit of a falling-out, and I said the best thing would be for him to manage himself. But you've got to realize Robert always wanted to be the boss of the band anyway. He finally got his own way.

HELEN GRANT (daughter of Peter Grant) Dad got Robert a very, very good deal after the demise of Zeppelin, and, actually, he never made any money out of that. That was a little bit of a fly in the ointment. Robert always said he'd had enough of the whole drug thing with Jimmy and that he didn't want to be around it anymore. But then, Robert's not the angel fucking Gabriel.

PHIL CARLO I never ever heard G say a bad word about Jim, but there were times when he'd go, “That cunt Plant.” Robert was the only one who could really piss him off—and did hurt him a couple of times.

ED BICKNELL (former manager of Dire Straits) I was sitting in my office one morning, trying to become a tycoon, and my secretary buzzes me and says, “There's a bloke in reception who says he's Robert Plant.” So Robert comes in, plonks himself down, and says he's looking for a manager.

I go, “Does Peter Grant know you're here?” And he says, “Well, I've written to him.” I say, “When?” “About a year ago.” I said I didn't want to end up being hung out of a window. We went for lunch in Walton Street, and Robert was extremely personable, very funny, and very, very committed.

We went through this romance, as you do, and I was fully aware he was romancing other people. He decided to go with Tony Smith, which was fine, though eventually he ended up with Bill Curbishley—who was exactly the right person for him.

DENNIS SHEEHAN (road manager for U2) My first tour with U2, I got a call from Benji to say he was at Rockfield with Robert, and would we like to pop in? I didn't tell the lads, in case it didn't happen. I told them instead that we were just going to have a cup of tea at this nice place I knew.

We pulled up to Rockfield, and Benji was standing there. He told me Robert was over at the house up the lane. So just as Bono was waking up next to me in the van, I drove up the lane to the top of the hill, and Robert was standing on the edge of the hill, looking out across the valleys. He turned around toward us, and Bono goes, “Is that Robert Plant?” I said it was. He goes, “Does he come and have his tea here as well?”

ROBBIE BLUNT A lot of what we achieved would not have happened without Benji. He would take on the responsibilities of three people on the road. When we were doing our pretour rehearsals in Dallas with the Showco personal assistant, Benji put the lights up and just said, “This is not acceptable.” He made the entire crew stay there the whole night, take the desk apart, and clean everything. That was the type of guy he was. In the studio, he helped me get a lot of my sounds. Indispensable.

ROBERT PLANT Phil Collins and I were both on the same label, and he'd had some dealings with Carson and mentioned that if I was doing anything, he would love to join as a contributor. He was really very concerned that it should be right. Considering it was a project that he was just visiting, he was a real contributor, and I was very moved by him.

ROBBIE BLUNT Phil didn't have a lot of time, recording-wise. We probably only had him for about five or six days. But we were pretty well rehearsed without him. And then he came out to Las Colinas in Texas. I think he thought it was going to be easier than it actually was.

BENJI LeFEVRE I think Robert controlled his own destiny, but Carson advised him on certain things. It was Carson who put the Es Peranza label together. But the first time any real management figure came in was Tony Smith on the first tour, on the back of Phil Collins saying he'd love to be the drummer. Robert said it's time for a playback, so there was a big playback, and I don't think G was there.

ROBBIE BLUNT Pictures at Eleven had four very good components that you could strip down and it would still sound really good. There weren't a lot of overdubs, not a lot of padding. Pat Moran was a fabulous engineer and would get me great sounds. We got there in the end, after we'd emerged from our own orifices.

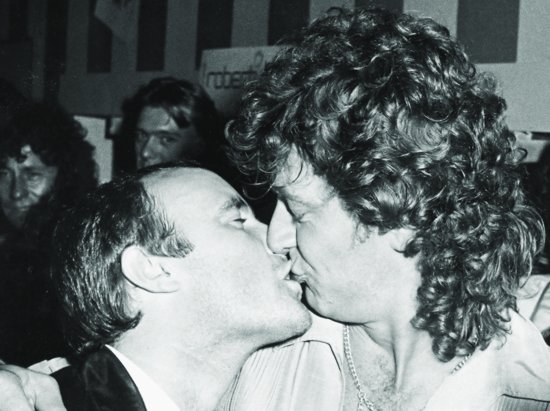

Plant snogs Phil Collins, New York City, September 12, 1983. (Ron Galella)

The album was like a melting pot of all these things we'd been involved with in the past. “Fat Lip” was the first thing Jezz and I really put down at Palomino, Robert's place. When we came back the next day, Robert had put this vocal on. It was like, “Where did that come from?” I do remember Robert playing us some Arabic or other world music, and for “Slow Dancer” we did try and push it in that direction. But most of the others just came out of the ether.

• • •

ED BICKNELL Robert picked up the ball and said, “I've got lots of music in me, and I'm going to go forth.” Jimmy, on the other hand, sat with his thumb up his bum and his mind in neutral and waited for Michael Winner to stick his head over the garden wall and say, “I'm filming Death Wish 90, and would you like to do the music for it?”

MICHAEL WINNER (director of Death Wish II) I'd lived next door to Jimmy for many years; I'd never seen him, never spoken to him. So I rang up the number, got on to Peter Grant, and actually Peter was very clever because although Jimmy wasn't paid anything … what he wanted to do was restore Jimmy back to creativity.

[Jimmy] rang the doorbell, and I thought, “If the wind blows, he'll fall over.” He said to me, “I'm going to my studio”—at the time he owned a studio in Cookham, later bought by Chris Rea. He said, “I don't want you anywhere near me, I'm going to do it all on my own.”

DAVE NORTHOVER (assistant to Peter Grant post-Zeppelin) Getting Peter to attend to business was very difficult. When Jimmy did the music for Death Wish II, I constantly had to make excuses to Michael, who would say, “What do you mean, ‘He's not available'?” The excuses got stranger and stranger. One time he rang and said, “Is Peter there, David?” I said, “No, he's gone to … the Isle of Wight.” “What's he doing in the Isle of Wight?” I said, “Well, he goes there and then … he flies back in a hang glider.” He said, “A hang glider? Good God, the man's thirty stone if he's a pound!”

PETER GRANT We stalled it a bit, but eventually Jimmy came up with the goods. But Michael wasn't happy. He sent some heavy down to my house to get the contract signed, but he was wasting his fucking time doing that. I just left him outside all night.

AHMET ERTEGUN (head of Atlantic Records) The members of the band and also the members of Bad Company were having trouble getting hold of Peter, and he was beginning to lose control of the musicians he was representing. Every time you called, there was always an excuse. One of the members of Bad Company said to me, “He must the cleanest man in the world, because every time I call he's in the bathtub.”

DONOVAN (Scots-born folk-pop singer) I got to know Jimmy … when he lived near Windsor, in the house he bought, twice, from Michael Caine. He was mourning because Bonham had died. I said, “Is that it?” He said, “That's it. No more Zep.” He took me down to a cottage. He said, “This is the Guitar Cottage. These are my guitars.” And they were all in little cases, maybe three hundred of them. I said, “Can I open one?” He said, “Yeah.” I said, “It's in tune, Jimmy!” He said, “They're all in tune.” It was Spinal Tap.

DESIREE KIRKE Jimmy had always had the shroud of mystery around him. It wasn't until later when I became good friends with Charlotte that I started spending more time with them as a family.

Charlotte and Jimmy really looked after me when I was going through my divorce from Simon, which was very unexpected. I didn't see too much of anyone else during that period, because usually what happens is once the star walks out the door, people forget you. But they were incredibly supportive. Charlotte would say, “Come down and spend the weekend in Windsor,” and it became almost like a family thing.

PHIL CARLO Charlotte used to say to my wife, “I love it when Jimmy's out of it. He's no trouble at all. It's when he's straight that he's a fucking nightmare.” We spent one Christmas with them. It was the weirdest Christmas ever. Jimmy is the only man I know that can look sinister in a Christmas hat. We all sat round the table for a haunted Christmas lunch.

JULIE CARLO Charlotte used to ring me at two in the morning, and I'd say, “Jesus Christ, I'm in bed!” She'd say, “Why do you go to bed so early?”

PHIL CARLO Poor old Rick Hobbs—who was camp, to say the least—had the plumbers round at Windsor. And the plumber had an assistant with one of those big pink Mohawks with safety pins and his legs tied up in those funny trousers they used to wear. Charlotte spotted him and screeched from a window on the other side, “Rick, I told you before, I don't want your fucking gay boys round here!” Rick went, “Charlotte, it's the plumber.”

When you worked for Jim, if you came out of it alive, you did well. Ray Thomas is dead. There's the guy from Plumpton who died. The doctor took me into his office at Harley Street and said, “I'm going to put my cards on the table: Jimmy'll be dead by Christmas unless you can get hold of him. There's nothing I can do anymore.”