29

Mighty Rearrangements

“The song remains the same!”

“No, it doesn't, motherfucker!”

—Diamanda Galas responding to a fan on her 1994 tour with John Paul Jones

DAVID BATES (A&R man for Page & Plant) I had some history with Bill Curbishley before my involvement with Robert, because I was a massive Who fan as a kid. So here was Bill managing Robert, and we all got on very well.

JUNE HARRIS BARSALONA (wife of Premier Talent boss Frank Barsalona) Bill is a terrific manager, and I would think that he and Robert have a lot in common as they've both grown up. If Robert wants to work, he and Bill will talk it out and decide what they're going to do. And it'll be much easier, on a more adult level.

DAVID BATES We were talking one day, and Bill said, “What do you think about the idea of Robert and Jimmy getting back together?” I said, “It would be amazing, but there's a lot of problems with that.” So he said, “There's a possibility that Jimmy might want to meet with Robert.” So we discussed how we might bring this up with Robert, because that would have been a very prickly conversation.

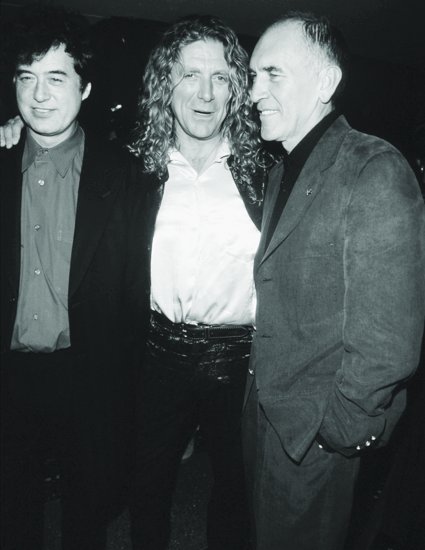

Page and Plant with Bill Curbishley at the Silver Clef Dinner and Auction, New York, November 13, 1996. (Evan Agostini/Liaison/Getty Images)

Was John Paul even mentioned? I think the way Bill and I were looking at it was like, “Shall we just do one thing at a time?” Just getting Robert to talk to Jimmy was a big hurdle. There wasn't really a relationship at that point. There had been a relationship, of course, but there were also a lot of things that had been left unsaid and that hadn't been dealt with. I think that over the years, all that stuff builds up.

ROBERT PLANT I realized that I missed Jimmy, missed his playing, so I was somehow going to have to deal with what was basically my own insistence on having nothing to do with any kind of Led Zeppelin rerun—which was pretty hypocritical at that stage, because I was doing Zeppelin songs with my own band.

DAVID BATES The meeting finally happened in Boston, at the end of Robert's tour. And that opened up possibilities of meeting again in England. Obviously, we knew all the stories of the various problems Jimmy had had. He'd dealt with his alcohol problem. He said to me, “I am now in control, and I'm okay.”

Because of my relationship with Robert, Jimmy wanted to get to know me, so we spent quite a bit of time together. And once again, the common bond was playing records. I just thought it was quite bizarre, cruising around London in my car with Jimmy, listening to music. I had been assisting Don Was as a long-distance A&R consultant while he was doing Voodoo Lounge, and I'd gone out to the A&M studios to visit the Stones while they were trying to pare down twenty-eight songs to however many were on the record. So I had a very early copy of the album, and Jimmy and I drove around London playing it. He listened to it in great detail, zoned right in to what was going on.

ROBERT PLANT The thing to avoid was us being gotten into the wrong hands and manipulated into ending up like a sort of animated Pink Floyd, if you like: roll out the barrel, the same old shit…. Like a Rolling Stones situation, where the lads get back together, and it's like, “Well, I remember back in so-and-so, and they're still pretty good.” Just being candy floss for some total retro occasion.

GLYN JOHNS (engineer on first Zeppelin album) The way Page and Plant treated John Paul in the '90s was disgraceful, disgusting. It's always the nicest ones who get it in the nuts. But he's happy enough, I think.

JOHN PAUL JONES I've never really understood why they did what they did. I remember one time when a journalist asked me, “What do you think about No Quarter?”—meaning Page and Plant's album title. And I said, “I always reckoned it was one of my best tunes.”

BENJI LeFEVRE (Plant producer and collaborator in the '80s) Jonesy not being part of the UnLedded thing was probably nothing to do with Robert and more to do with Jimmy wanting to control everything.

VANESSA GILBERT (friend of Page and Plant) Every time I would see Jimmy or Robert after all that jazz, the first thing out of their mouths would be, “Have you heard from John Paul?” I did wonder why they'd left him out. I think it was just egos and fear. Easier not to deal with him.

ROBERT PLANT It reads as bad blood, but really it's just handbags. Handbags with Jonesy—it's a great name for the next solo album.

JOHN PAUL JONES [at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction] I remember doing the sound check on my own—no sign of the others, so not much had changed in that department. There was a bit of fuss about Jason playing from some quarters yet again. I credited Peter Grant, because it was pretty stupid that he wasn't there.

ALAN CALLAN (former president of Swan Song in the U.K.) I used to invite Peter up to the golf tournaments. He'd come up to Gleneagles and stay for a week. At the Scottish Open, I used to put him in among all the golfers, Ian Woosnam and Nick Faldo, and he'd sit there and charm the pants off them. One night we're sitting there, and Ken Scofield says to me, “Who's your friend?” So I said, “He used to be the manager of Led Zeppelin.” Norman MacFarlane goes, “Och, Ken, ya must know who Led Zeppelin were. Jimmy Page is mah favorite guitar player.”

ED BICKNELL (former manager of Dire Straits) People would say to me, “How can you be friends with Peter Grant?” And I'd say, “Well, the person I know bears no relationship to the person I've read about.” We would get together almost every week and go to the local gastropubs, where he would regale me with stories. Most of them were not about Led Zeppelin, though. They were about the Bo Diddleys and Little Richards of this world—probably because they were even bigger characters than the guys in Zeppelin.

Peter became this rather benign figure in the neighborhood. I like to think he was at peace with himself. I don't think he ever did a drug or had a drink again. He just used a little homeopathic dropper with some flower remedy in it, and he would go for a walk along Eastbourne front every day. He'd say, “I'm going to be down to X stone by my sixtieth birthday.” He was completely inspired by his grandchildren. He was happy to stick his toe in the music business waters, but he didn't want to come back to it at all. He knew you couldn't repeat the experience.

WILLIE ROBERTSON (insurance broker for Zeppelin and Swan Song acts) I had lunch with Peter at Morton's, and he was a totally changed man—lovely, quiet … lost all that “Fuck this and fuck that.” And, of course, he'd lost a lot of weight.

AHMET ERTEGUN (head of Atlantic) He came to see me in my hotel room, and when I saw him I couldn't believe it was the same man. He must have lost 250 pounds, and he was dressed in a very well-cut suit, a smart necktie … he looked like a banker. He was a thoroughly different person, but he still had that marvelous glint in his eye and that very warm smile.

ED BICKNELL He used to do these chauffeuring jobs for weddings with a bloke called Lord John Gould. He would put on a cap and uniform, take the happy couple to the church in Hellingly or wherever, and then drive them off to the Grand Hotel in Eastbourne.

LORD JOHN GOULD (vintage car enthusiast and friend of Peter Grant) I remember the first wedding, we were sitting outside munching a sandwich while they were getting married, and then we drove off. We were paid £30 each in cash, and I remember Peter saying to me, in his inimitable language, “Ah, fuckin' 'ell, John, first cash I've 'ad for years … lovely!”

ED BICKNELL One night he'd been asked to judge a talent contest on the pier, and he asked if I fancied doing it with him. So a couple of weeks later, there's the managers of Led Zeppelin and Dire Straits judging these dreadful fucking bands at the end of Eastbourne pier.

I went up with Peter to the first “In the City” conference in Manchester. A group of managers had dinner at the Piccadilly Hotel, and we were all talking about how it was back then. At about one in the morning, Peter turned to Andy Dodd and Elliott Rashman and said, “I think you boys should go to bed and get your rest. You've got a big day tomorrow.” And the two of them, rather sheeplike, toddled off to bed!

The next day, Paul Morley did this appalling interview with him. His whole line was that of a left-wing NME writer. He'd brought this kind of bouncer onstage to guard him, which was a joke that backfired completely.

A slimmed-down Peter Grant with Phil Carlo at the first “In the City” conference, Manchester, 1992. (Courtesy of Phil Carlo)

MARTIN MEISSONNIER (Paris-based world-music producer) Malcolm McLaren wanted to make a film about Peter. Some people think that is strange, because they see Malcolm as the great punk inventor. But Malcolm never cared about punk; the only thing that interested him was creating hysteria and making himself famous through that moment. The thing that fascinated him about Led Zeppelin was the relationship between Peter Grant and organized crime, and he talked to Peter extensively about it.

MALCOLM McLAREN (former manager of the Sex Pistols) Managers like myself were very conscious of the fear he used to inspire. When he entered a record company building, the silence was total. His stature created an air of menace, a catalyst encouraging acts of violence from his volatile entourage…. Grant needed the camaraderie of hard, dangerous men who gave him a sense of power. The harder they were, the tougher he felt, and only then was his desire for control satisfied.

DAVID DALTON (biographer of Janis Joplin and others) Tony Secunda asked if I'd be interested in ghosting Peter's autobiography, so I flew to Miami to meet Peter. He said, “Everyone always talks about the dark side of Led Zeppelin. I want to talk about the happy side.” Before I left, I collected some shells for my son on Miami Beach, and he seemed very touched by that. He said, “You must be a good dad.” I thought, “Here's this supposedly monstrous man who's touched by something so simple.”

WARREN GRANT (son of Peter Grant) The fondest memory, I think, is when the kids were born. Seeing him with the grandchildren and how he was with them … this unselfish man who just wanted to please everyone else.

DESIREE KIRKE (ex-wife of Simon Kirke) Peter came to Miami on business in 1993. He'd lost a lot of weight, and his head was really in a good space. Then, at the end of 1994, I went to see him at the flat in Eastbourne. As we went to leave, Helen came running out and said, “Dad really misses you, can you come and see him again?” And I couldn't get to see him again, and it was very sad.

SIMON KIRKE (drummer with Bad Company) I last saw him at a Bad Company show in 1994. It was at the Mean Fiddler in Kentish Town. He came back to the hotel afterward and sipped on a club soda as we went down memory lane. I gave him a teary-eyed hug, told him I loved him, and went upstairs. And that was it, I never saw him again. He was the best manager I ever worked with.

ROBERT PLANT Backstage at London's Wembley Arena in 1995 [was] the last time I saw Peter, and he was a kind, warm, frail guy who invoked so many wonderful memories. He was a different person from the man I saw at the end of the '70s. He was clean, his vision was clean. He knew that he'd moved mountains, that he'd changed the world for artists.

HELEN GRANT (daughter of Peter Grant) It was just like they were so pleased to see each other all again. All the years had gone by, with all the crap and the not talking to each other.

ALAN CALLAN I was very touched when the family asked me to give the eulogy at Peter's funeral. I knew what I wanted to say, but as the church filled up, I started to feel terrified. I'm looking out, and there's Jimmy and Robert and Jeff Beck and Paul Rodgers, and I think, “How can I possibly express Peter's life to these people, some of whom had known him even longer than I had?”

Lord John Gould gets up and starts wittering on about life in Eastbourne, and I'm thinking, “Who is this guy?” And then comes the ultimate moment, when the coffin is picked up and on comes “We'll Meet Again.” It transpires that Peter has organized the music in advance. It was brilliant. And then we all hared off to the reception, where Jeff Beck wandered around Peter's car collection, going, “Look at the engine on that …”

PHIL CARLO (assistant to Page in '80s and early '90s) I've never seen so many people with dyed hair. Beck, Jimmy, and the bloke from the Pretty Things—a very strange man who wore black tights but had a big fat stomach and looked like someone out of a German porn film.

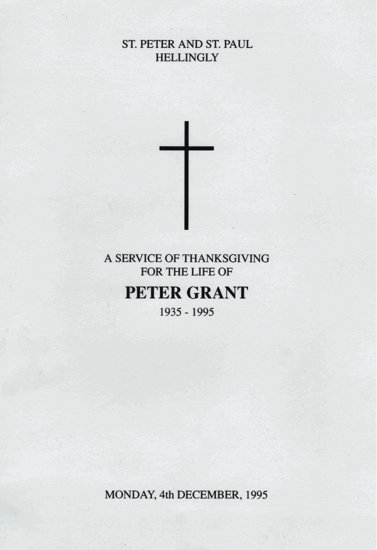

Order of service for Grant's funeral, December 4, 1995. (Courtesy of Phil Carlo)

DESIREE KIRKE I actually went up to Gloria at Peter's funeral. Something compelled me to tell her that he'd really, really loved her. She just kind of looked at me, stunned. I don't know if she even knew who I was.

ED BICKNELL I think about him almost every day, and I don't know why. He almost became like a father figure to me. He was incredibly interesting, and not just about music. He would say things that were really on the nail. It's not often I'd say it of another man, but I loved Peter. And most of the people I know who knew him loved him, too.

• • •

DAVID BATES The first Page and Plant reunion I saw was April 7, 1994, in Buxton—the Alexis Korner thing. I'd just seen Blow-Up again, so I suggested “Train Kept a' Rollin' ” as an encore. They just jammed it, and it was brilliant.

The Page-Plant project slowly evolved, and the next question obviously was, “Who's going to be in the band?” Charlie Jones was inked in straightaway, because his relationship with Robert was long and highly complex. He ended up going out with Robert's daughter Carmen and eventually married her. Charlie therefore at this point was Robert's bass player and Robert's son-in-law. He was also Robert's conscience, because Charlie and Carmen were two of life's beautiful people. Michael Lee wanted to be John Bonham and could do great Bonzo-type things. So that was the rhythm section.

ROSS HALFIN (photographer and friend of Page's) I never thought that much of either Michael or Charlie. Michael was an okay drummer, but he was just a thrasher with no real finesse. And Charlie was just there 'cause he was Plant's son-in-law. As for Porl Thompson from the Cure, there was just no point in him being there at all. Personally, I think Jimmy put up with a lot from that lot. There just wasn't a nice vibe around them. Maybe it's just because I was Jimmy's guy, but there were always two very firmly etched camps. Jimmy's camp was a very small camp, and Robert's was a very large camp.

DAVID BATES The first rehearsals were at the King's Head at the end of the Fulham Road. Why? Because it was cheap. It was just the four of them. And nobody fucking knew they were in there. I remember going into the pub and thinking, “These people have absolutely no idea what's going on upstairs.”

I was getting huge pressure from above—from Alain Levy and Roger Ames at Polygram—because they needed this album to be big. I ended up having a row with Robert and Jimmy about singles, because we needed something to sell this thing. And as we all know, singles are anathema to these guys. We all have those horrible moments that you look back on with regret, and that's one of mine, personally and professionally.

This thing came up with MTV, and, obviously, it was one of the biggest coups they could get. How fast does the word go out? How fast is the speed of light? Within days, Coca-Cola and Pepsi-Cola and Amex are queuing up outside Bill's office. I went to lots of meetings with Bill, but Robert was not keen on the sponsorship thing—because he does have integrity. The amount of money they could have made, had they gone down the sponsorship route, was millions upon millions. And that's partly because everyone's thinking the same thing: If a Led Zeppelin reunion ever happens, we want to get in on it.

Meanwhile, we're in a very fragile place here: we're trying to put two human beings back together again.

ROBERT PLANT The offer from MTV really was so fortuitous. I'd started going to the Welsh mountains again, and reading the old books about mythology and Celtic history…. I missed the kind of thing that Jimmy and I had.

DAVID BATES Jimmy and I stayed at the Ynyshir Hall hotel in Powys, and we would drive over to Robert's farm in the morning. One day Robert wanted to go out for a drive into the wilds. We went for a bit of a walk in these woods, and we got to this place with the most amazing view and with the most incredible sunset. At that moment, he started singing, “There's a feeling I get when I look to the west …” Then he went, “This is it.” And I thought, “Fuck me, this is obviously the inspiration for it!” Then we got back in the car and drove off again. I was made for life.

JIMMY PAGE Robert and I went into a real dark, dank rehearsal studio in the north part of London, and we just had the tape machine, some North African rhythm loops, and my guitar, and it was, “Let's see what you can do.”

ROBERT PLANT “Yallah” is a loop put together by Martin Meissonnier. He's married to Amina, the Tunisian singer, and he worked with Khaled and Youssou N'Dour and so on. I met him when I played in Paris, and I told him that Jimmy and I were thinking of working together, and could he come up with some drum loops from stuff that he'd recorded in Mauritania? I said, “Let's get some real slinky loops that are coming from an African or a desert sound.”

MARTIN MEISSONNIER He said they were looking for new ideas and rhythms, because they didn't want to do the old rock 'n' roll by itself. He said he would come back the next week, and he actually came. I had lots of loops I was using for Amina and for soundtracks, so I put about twenty together on a cassette for him. Some of them I had recorded in the desert. They ended up using four of the loops, and they invited me to see them recording in London. Jimmy was truly excited as well.

Hossam Ramzy (Egyptian arranger on No Quarter and the Page-Plant tour) They wanted an Arabian, Middle Eastern feel, and the closest one that Robert, I believe, has been in touch with, of course, is the Moroccan side of things. Unfortunately, the kind of direction it was going in … was a full luscious Arabian flavor of sound … but it was just far too much falafel in the dish. The sound of Led Zeppelin is, in my mind, a combination of extreme richness with minimalistic kind of thrusts that combines various genres of music.

The idea was, “How do I put my style and the genre of music that I bring side by side in the same bed?” That was extremely difficult, and we had lots of rehearsals. [With “Friends”], Jimmy has a very particular tempo that he likes to play in, and to get that tempo right … this took several weeks of rehearsals. [With “Four Sticks”], the difficulty was the counting. That's a tough one, especially for the Egyptian musicians and the Arabian musicians.

DAVID BATES We went to Marrakech, and they just set up with the Gnaoua musicians in the Djemaa el Fna. They got changed in a bar across the road. Jimmy was incredibly nervous. We crossed over into the square; nobody knew who they were. Martin had prepared these tapes, and they played along to those. American tourists were doing a double take: “It's Led Zeppelin! What the fuck is going on?”

At some point during all this filming, Jimmy wanted to go back to the hotel. He was highly agitated. Now I had given up drugs, and I had even given up smoking. In fact, I had a no-smoking policy in my car. Jimmy got in and he was smoking away, and I said, “Jim, put the cigarette out.” He fucking lost it, and I saw another side to Jimmy Page. It got very ugly. Because I have a reputation as well, and I lost it. I said, “Jimmy, if you're a friend, and if you're going to work with me, you have to fucking understand. Where's the respect in this? I'm not your fucking chauffeur.”

I could have given in, but it probably would have happened in the future. The person who was in between us was Bill Curbishley, who wanted one of us to back down. And I wouldn't; I'd have fucking knocked him out. And it's something I regret, because you look at it on a piece of paper, and you think, “Why fall out over something like that?” But we did, and it was a huge shame. From that day on, it affected Jimmy as to how he talked to me or dealt with me. It was sad, odd, and weird.

MAT SNOW (former editor of MOJO) There was still this whole thing about the unfinished business of the band: what Led Zeppelin could have been, which would have been a much more equal allocation and presentation of talents than had been the case before, where it had been very much Page's baby and something that caused Plant, in particular, to chafe. When the relationship picks up again, it's very much on Plant's terms because he seems to be getting better, whereas Page is floundering. Even though you couldn't say in 1994 that Plant had set the world on fire, at least he was getting an awful lot more kudos by trying things out and not just wanting to relive the myth.

BENJI LeFEVRE Robert came round for a cup of tea and said, “I don't know about this…. What am I going to do?” I said, “You owe it to yourself to find out, and you owe it to Karac to find out if you could ever make it work. But you have to make sure you can get out of it if you don't like it.” Two weeks into the tour, he said, “It's insane. All I want to do is get up in the morning and play tennis, and Jimmy just wants to stay up all night.”

JANINE SAFER (ex-Swan Song in the U.S.) A friend of mine did a bit of PR for them on the Unledded tour, and she said it was all she could do to stop them from clawing each other to death.

LORI MATTIX (former L.A. groupie) It was quite flattering when Jimmy met Jimena, and she looked exactly like me. She was nine months' pregnant with somebody else's kid. She had that baby and had him adopt it and popped out three more babies, and my girlfriend saw her in a club in London with a twenty-one-year-old boy.

PAMELA DES BARRES (former L.A. groupie) He got his heart broken, finally. It was the Brazilian. Apparently that was really devastating to him.

DAVID BATES Because it was Robert and Jimmy, which was the nearest thing many people had seen to Led Zeppelin, the fucking hoo-ha on that tour was incredible. My wife and I went to Philadelphia to see Jimmy and Robert play at the Spectrum, and Bill Curbishley ambled across to the side of the stage where we were and said, “Dave, when I say go, you go.”

We go sailing out the back of the Spectrum with six outriders escorting us, and the convoy goes right from the Spectrum to a private airstrip on the outskirts of town. And we board a private jet that takes us to New York. We've gone from a nice quiet little tour with Robert to chaos and mayhem. So I know what it must have been like to travel with Led Zeppelin in the '70s.

RICHARD COLE When you consider that you could see Zeppelin in 1977 for $7, and now it was $125…. Frank Barsalona told me they made $50 million on that tour. He said to me, “They've made more money on this tour than they did in the whole live career of Led Zeppelin.”

HOSSAM RAMZY On the tour itself, just to stand on the side of the stage and listen to the five notes that Jimmy plays as the introduction to “Since I've Been Loving You,” that is worth all the musical experience in my life.

JIMMY PAGE It was an incredible extravaganza to take rolling around the world, with these Egyptians who had no camaraderie among themselves whatsoever and who were all willing to stab each other in the back.

ROBERT PLANT The Egyptians had their own internal power struggles, but we managed to sort ours out. Which is why, at the end, Jimmy and I were able to hug each other farewell, knowing there would be another time.

MARTIN MEISSONNIER I thought they could have gone much further with the music than they did, and I think Robert was really looking for that. And then what happened later was that Robert started working with Justin Adams to go further in that direction.

JIMMY PAGE The most obvious thing for us to do was to go back to the four-piece unit that we knew best and has always worked best for us.

ROBERT PLANT It's daft, really, I suppose, going around looking at roadside buildings that have closed down in Banks, Mississippi, where Robert Johnson is supposed to have come in on a break between Son House and Bukka White, picked a guitar up after he'd been away for a year, and improved beyond all recognition. Clarksdale is a very sleepy town now, but it carries a history that had an amazing effect on both of us…. Being obsessed with that music, I wanted to go there. I guess I was just forty years too late.

JIMMY PAGE (speaking in 1998) The greatest problem with a band that plays organically is someone to record it. We're fortunate with Steve Albini, because he really knows how to equalize using microphones, the old science of recording. Plus, it's been really wonderful working at Abbey Road in that great room.

STEVE ALBINI (producer of Nirvana and others) Walking into Clarksdale was much more collaborative, I think, than Jimmy and Robert had been in Led Zeppelin. Zeppelin was Jimmy's band; he hired Robert to be the singer. And then in the intervening period, Robert had gone on to become quite successful on his own. I think Jimmy respected that. Now he was working with Robert as a peer and [a] comrade, rather than feeling responsible for the record as its auteur.

Both of them were very conscious, futilely, of not resuscitating the ghost of Zeppelin. But it was a shared experience they drew on quite naturally. Jimmy has enormously varied tastes, though. He kept talking about how much he liked the over-the-top aggression and adrenaline of the Prodigy.

DAVID BATES By Walking into Clarksdale, I'd got clinical depression, so I was on gardening leave. To try and find someone who would produce the record and be honest, that was the issue. In theory, the honesty and purity of Albini's approach was perfect; in retrospect, it was not such a great solution, but there was nothing I could do about it.

MARTIN MEISSONNIER It's funny how the follow-up to No Quarter is just a real rock record. I don't think Steve really understood Led Zeppelin. He applied loops, but he didn't know how to use them. But it's complicated when you add such huge egos into the mix.

ROBERT PLANT Everything had become remote. I began to feel intimidated, committing myself to large parts of touring.

DAVID BATES I believe Jim had got up to his old politics, in terms of the way he was treating band members. You see, there's a big elephant in the room, and no one talks about it. There are things from way back—some very heavy things that really hurt Robert that were never addressed. The issue of Jimmy not being at Karac's funeral is part of it, but it's not all of it. It gets even bigger than that, and when you start delving into it and you hear the stories, you sit there and go, “Are these people his mates? Do they not realize what this man is going through?”

I'm not a psychologist or a therapist, so if you think I'm going to be the one who goes, “There's the elephant, let's fucking deal with it,” you're wrong. I'd just hope that Robert and Jimmy could sit down and talk about it. But you know what, the elephant is so fucking big now, I don't know if they ever will. It's okay when Jim is making overtures to Robert, but eventually the overtures stop, and then we're back to where we were before.

ROBERT PLANT We were going 'round and 'round all those big gigs in Germany, where everything looks like a storeroom for some strange new flying machine, and you don't know where you are or what you are. I'd done it for years and years, and to prove what? I'd rather play a folk club in Birmingham and have a bit of fun with people.

ROY WILLIAMS (live engineer for Plant) They did a gig for Amnesty International in Paris, and I think they were due to go to South America. And Robert just said, “No, I've had enough.” Then he came back here and started talking with Kevyn Gammond.