My mother met my father by way of a blind date. A nursing classmate was concerned that she didn’t have a boyfriend. The friend knew some young men from Pittsburgh, so after coming to her house, it turned out that the young men were from Union Town. The friend said Horace (my father) was older (by 11 years), and that she needed to introduce her to someone else younger. So she introduced my mother to my father’s younger brother, Henry. Uncle Henry came to her house to meet her, and after meeting him, my mother felt “he was dull as dish water.”

So once again, “the friend” decided to introduce my father to my mother but said “Bob (my father’s nickname) was older” than she was. My mother was twenty-four at the time and didn’t know how old my father really was. He asked her how old she was and then made his age nine years older. Before finding out his true age, my mother told him that if he had been two years older, he would have been too old for her. What she soon found out later was that he was actually eleven years older than she was and not nine. My mother did not know he was eleven years older until they were about to be married, and he had to reveal his actual birth date when they had to apply for the marriage license.

The girl that introduced my parents to each other was Mary, who lived in New York. Mary met her husband in New York, and she was worried about my mother. She was concerned about her going to heaven, and my mother informed her, “I will be going to heaven.” Mary would often write my mother all of these biblical phrases and send them to her. My mother would then tell Mary she knew where she was going and that was to heaven, and then the woman stopped writing her, and that was the end of their contact.

When they were going to get the marriage license, my mother informed my father, “You’re going to have to tell me your birth date because we have to put it down on the license.” When my mother asked my father why he never mentioned his real age, he never acknowledged it and never said a word in reference to it.

When she found out how old my father really was, she called her mother and said, “Mama, he’s eleven years older, and that’s too old.” Her mother said, “Honey, what’s two more years? I don’t want you to die with Miss on your tombstone.” She further repeated, “What are two more years?” And my mother replied, “Mama, he’s forty. He’s not thirty-eight.” Her mama said again, “What’s two more years?” My mother then dated my father four years before they got married. She was working in the operating room at the time, was twenty-eight by that time, and was twenty-four when she first met my father.

My mother remembers a lot about my father’s early life. She remembers that my father was from a small town with very few black people in the neighborhood. My father and his two sisters Ethel and Eva were the only black students in the school building. My father had a scholarship to Howard University and Temple, but he was told to stay home, because he was needed in the community. Uncle Jim was supposed to go to school for one year then go back to Union Town, and then my father was supposed to go to Howard for one year when Uncle Jim returned.

They were supposed to rotate, but Uncle Jim decided, “Why do this? I might as well stay and finish,” remembers my mother. Uncle Jim and my father had a difficult time for a long time after that because my father regretted not being able to attend college. So he stayed on the home front and took care of his mother and father and bought them a house and worked in the mines up until the time he left for Washington, DC. In the meantime, Uncle Jim had a lot of good ideas; and, eventually, he had this idea about starting a family business.

My mother remembers that they went to school and couldn’t even afford the 3 cents to ride the bus to get to school. They walked. It was a small area. There weren’t that many black people there, and it was very segregated. My father went to school with white people, and there wasn’t a lot of racial tension at that time, because it was only the three of them. However, there were certain areas in the neighboring town you could not go to.

When my parents would go to my father’s high school reunions many years after they were married, sometimes they would be the only black people in attendance. The reunions were held in southern areas. It was very prejudiced, and when they would go, the white women would gather around my father. Knowing where they were and the mind-set of many of the people there, my mother would stand up to let these women know that my father was there with a black woman.

After four years of dating, my mother decided she wanted to get married. It first began by my mother’s supervisor calling her into her office and saying, “It’s been a long time, and I think you two ought to be thinking about getting married.” My mother said she didn’t say anything and went back home and told my father what the supervisor had said. When my mother returned to work the next week, she told her supervisor that she would be getting married in February.

The supervisor then wanted to know what had happened and wanted to know all the details leading up to the decision. When it got closer and closer to their wedding date and every time they said they would get married, something would happen. For example, the boiler would break at the laundry or something else would happen or something else would break.

My mother had to eventually say to my father, “We’ve been going together for two years, and if we decide it’s not going any further, then we need to make other arrangements.” Then the two years were up, then it was three years, then it was going on four years. Everyone, including my mother’s supervisor, was looking at her and said, “You need to get married.”

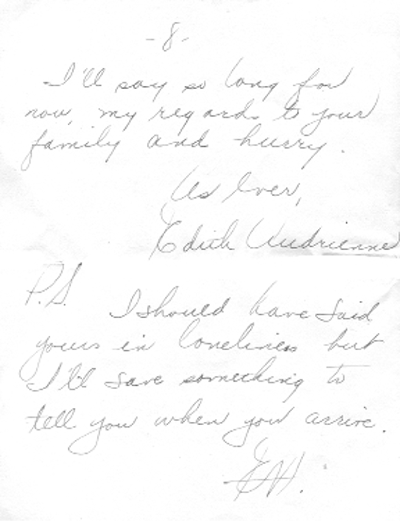

On many of the letters that were written to my father, my mother would often sign them Edith Audrienne. Audrienne, which later became my first name, was not the name given to her at birth. My mother was given that name when she was working in the operating room, possibly by a supervisor. My mother added Audrienne after her first name Edith and often signed her letters to my father with both names.

When the supervisor told her, “You have been dating for a long time,” my mother confessed that “they told us nothing about contraceptives.” She said the girls were getting pregnant, and someone named Ms. Robinson was telling them about contraceptives and by Monday they had fired her. She was gone because she was trying to provide the girls with information on birth control.

In the operating room of Freedman’s Hospital School of Nursing, where my mother was assigned, there was a container full of all these unusual things that my mother didn’t recognize, and the fellows would just laugh at them. At that time, my mother had never seen a condom before; and even though they would use them during surgery, they wouldn’t tell the young nurses about contraceptives or what they were used for.

In the meantime, the girls were getting pregnant, and the fellows weren’t getting married to them, and then they would send the girls home. So when Ms. Robinson said she would tell the girls about contraceptives, someone soon told the director, and they fired her. It was so sad because so many of the girls who needed to know about birth control were getting pregnant and would be sent home. That was the first time my mother had actually heard about contraceptives, even though she was a nursing student.

After my mother’s supervisor suggested that my parents should get married, my father didn’t say anything because they had already previously set the date for two years prior. So when they finally got married, it was in their apartment in Washington, DC, on Benning Road, NE; and the minister came to the apartment and married them. My mother doesn’t remember being charged any money for the ceremony. She just gave him a check for his time and service.

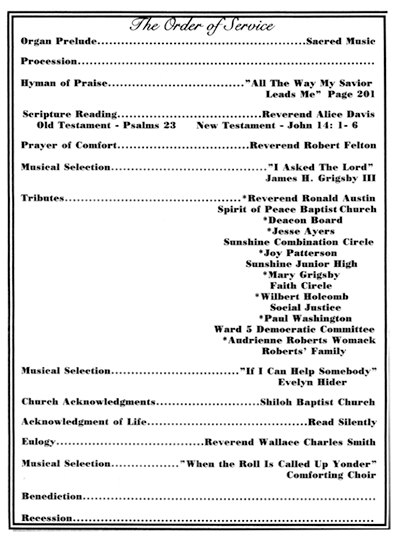

The minister was Reverend Earl L. Harrison from the Shiloh Baptist Church. They were married on February 6, 1954. At the time, my mother attended the Shiloh Baptist Church, and my father and his family were Methodists. When we were young, my father got baptized in the Shiloh Baptist Church years later with my oldest brother, Horace Jr.

When my mother had the conversation with my father, about how many children they wanted to have, my father answered by saying, “Yes, Robbie. We’re only going to have two children.” And my mother was in agreement and said, “That’s right!” My mother said my father was very careful about birth control. She said she was a hot sister, and she knew exactly when she got pregnant each time. My father didn’t say a word when my mother told him she was pregnant again for the third and fourth time.

Her in-laws would often say, “After all, they got all them children.” So eventually they stopped giving Christmas presents, because they said my parents “had too many children.” When the in-laws and my parents would go on family trips to New York, they would all have breakfast together, and then everyone would go to their separate hotel rooms.

When they were going to dinner, the in-laws were supposed to call so they could meet up. On one occasion, my parents waited and waited and waited for a call. Finally, it started raining, and my mother called and asked, “Are you all ready for dinner?” They replied, “Oh, we already had dinner, and we’re ready to go home.” My father was extremely upset, because they all came together but somehow got out of the loop. My parents then had to go out and find some place to eat, and when they were ready to finally go home, it was thundering and there was lightning.

My father said, “I will never go out with them again.” After my mother thought about it, she said, “If they didn’t want to be bothered, they should have said so.” Even after that, whenever anyone in the family would get sick, my father’s family would say, “Send Edith.” Since she was a registered nurse, they felt she was the one to service the sick and shut-in in the family. My mother would always be the one they would be volunteering to do the care giving.

My mother fondly remembers my father’s Aunt Bessie and Uncle Henry who lived in Mount Pleasant, Pennsylvania. She remembers them having a toilet in the basement that wasn’t connected. Uncle Henry once told my mother, “I wish I had seen you first. He [referring to my father] wouldn’t have got you.” Mama said Uncle Henry was a character. She remembers there not being any heat in his house. They would sit on chairs around the fireplace to keep warm.

When my mother reflects on my father’s days at the family laundry, she says there were many workers at the laundry that didn’t like my father. She said the workers believed he was a little difficult. She remembers that there was also a second laundry on Rhode Island Avenue, NE (Washington, DC) that he and his brothers rented and operated for many years after the closing of the first laundry.

When Uncle Jim was a doctor and while working at the laundry, “there would be people who would want him to do their laundry for free. Even when you have a business, you can’t do work for nothing,” my mother said, “especially when you got a great big family and you have all these friends who are doctors.” This customer came up who had a tourist home and said, “Tomorrow’s a busy day.”

He had forty sheets and had a busy business. He would say, “Jim said you all would do my laundry, ’cause I need them for tomorrow.” There was also a consultant that would advise them about their business. The consultant told my father, “You are working your machines to death. You can’t run a business like that.” But they were still doing it. “They would still overwork the machines,” my mother said.

My father and his brothers would do all the work, and they weren’t getting a salary and were continuously working the machines to death. Mama was getting ninety free diapers a week and washing diapers in the machines, and Uncle Henry once reminded her, “You’re getting more diapers than everybody else.” She was getting ninety diapers and still washing diapers. She had to agree with him because what he said was the truth.

My mother felt that the laundry business was supposed to bring the family together. However, one of the beliefs that they had was that if you had the family working together, then you could cut down on expenses. On many occasions, when they got to the cash register, there would be a note stating, for example, “Edith Roberts took $50 and signed her name.” When someone asked, “What is this?” The response was, “The other manager let us borrow money from the cash register and put her name down.” However, you wouldn’t know if that was true or not.

Kelly was one of their friends and was a driver for one of their laundry trucks. He was absent one day, and a fellow came up to the door and asked, “How many sheets can you sell me?” They soon found out that Kelly, the driver, was stealing the sheets and selling them and turning in a slip at the end of the transaction so they could get reimbursed. As a result, they had to buy more diapers, because the drivers where practically giving the diapers away and stealing the money.

They didn’t know all this was taking place until the day Kelly was absent from work. They were doomed because they had no clue Kelly was ripping them off like that. They were losing money but still had to have enough money to pay the workers. My father wasn’t getting a salary, much like the rest of his brothers. Nobody could get paid. They would give him $10, $15, but not enough to buy groceries. Kelly could have been ripping them off for years, and to think they didn’t know what was going on until that day Kelly was absent and the man wanted to know “how many sheets.” They were going into the cash register and would say, “They let us do that.” Then they wrote a note that said, “I took $50.”

My mother remembers the business eventually ending because they found out that the money wasn’t coming in. The money was going out but not coming in. They had a laundry in NW, they had the big laundry on Minnesota Avenue, and then they had a place where you could pick up laundry. At that time in history, white people were starting to take in black customers, so by that time, black people had more choices or laundry services to pick from.” My father was skilled as an engineer and invested a lot of his time and skills in trying to maintain the business, just as his brothers tried to do for many years.

On the subject of my father’s willingness to join the service, she remembers my father talking about why he didn’t go to the service, even though he wanted to. Even though he was a skilled engineer, he didn’t go into the service because they told him he could stay home. They told him he couldn’t go. She said they said he was needed on the home front, even though they eventually took Uncle Henry into the service. After that, my father and Uncle Jim had made an arrangement for college. They were going to take turns attending college, because money was very scarce at that time. “If you couldn’t get 30 cents for travel, money was scarce,” Mama remembers.

After the college situation, my father and Uncle Jim were upset for a long time, a very long time. By the time Uncle Jim finished college and decided to start the laundry, my father had bought his mother and father a house. After Uncle Jim came up with the idea about starting the laundry, he told my father about his idea. My father thought it was a good idea and made arrangements to come down to Washington, DC.

He then stayed in Uncle Jim’s house in the basement of his house on Kearney Street. My mother remembers my Uncle Jim would have these parties at his house and would invite my parents to attend. Then eventually Uncle Jim decided that my parents traveled in a different circle, so soon decided they didn’t need to invite my parents anymore.

My mother remembers how close my father was to his nephew Ronald Palmer. Ronald was his sister Ethel’s only son. His sister and her husband couldn’t afford to take care of Ronald, so they asked Uncle Jim to let him stay at their house on Kearny Street. They asked him to help Ronald out, and by the time Ronald graduated, he needed some money to go to school and some place to stay. He originally stayed with my father’s parents, James and Sallie, in Mount Pleasant/Standard Shaft before leaving to live with Uncle Jim in Washington, DC.

Ronald would take the laundry to the universities, and they would say, “Here comes the laundryman. Here comes the laundryman,” and Ronald would say he was so embarrassed. My mother said, “He eventually met his first wife, Euna. She was the secretary or worked in the office at the time, and Ronald was working and going to school. Jim arranged to have Ronald’s money sent to the school. Euna was older than Ronald and would often invite him to her house.” My mother remembers she was about her age at the time, and Ron was about eight years younger than Euna.

Ronald knew how old she was; but his mother Ethel didn’t know until Euna spent the night with them, and she asked Ronald, “You know she looks like a woman about thirty years old,” and she actually was. Ronald was spending the weekends with Euna, and someone told him that it was time that he thought about getting an apartment for two, since he was spending the weekends over there at her place so much.

My mother remembers exactly when my father was first diagnosed with prostate cancer. He had been going to the doctor all along. My father was going to his doctor, and my mother was going to her doctor. They were going to their own doctors. My mother said to my father, “You know one thing, you haven’t had a prostate exam,” and she said she couldn’t understand why his doctor didn’t schedule him for a prostate exam. She said, “They weren’t doing too much talking about prostate cancer [then], but now they’re saying they don’t need to do the PSA. Men don’t need to do it. It’s pitiful. You get a false negative and a false positive like the breast, like they talking about the women and the breast.”

When my mother took my father to the doctor and told him, “He needs to have a prostrate exam,” by that time, the doctor said, “He has prostate cancer. He will have to take medicine forever.” So when they took him back, they said, “No, you won’t have to have medicine. We’ll do watchful waiting.” Watchful waiting means “you’re waiting” for the cancer to grow back. They said to my mother, “He’s got cancer, and it’s gone to the bone, and it’s your fault.” My mother told him, “Cancer spreads, doesn’t it?” So now they don’t do watchful waiting, but unfortunately, that was a strategy that they did practice during my father’s ordeal at that time.

The doctor said it was my mother’s “fault” because she was supposed to go back every year and take him to the doctors, and when she went back to the doctor, “now they’re saying watchful waiting is not the way to go.” My father was already in his eighties by that point. My mother remembers, “With the watchful waiting, they were still waiting, and by that time, it had already spread. Bobby had to go and take all these therapies, and he had to take special medicine. They had to go to Providence Hospital. They had to give him shots.” She would take him over there to get the shots, and they would then put him on medicine. They wanted my mother to pay $600 a month first, and then they would send the bill to Medicare. My mother said, “No, no, no, no, $600 for the medicines for his shots. Medicare was supposed to be doing something.”

There’s a PSA number that they go by, and it’s supposed to be 0-4. My mother was taking him to the doctor, and the doctor was charging all that money. Once when she took my father to an appointment, the doctor then sent him into the hallway. My mother then asked my father, “Wait a minute, wait a minute. Why are you out here?” And he replied, “I’m okay.” When she looked at the PSA, it had said 15, and she told the doctor, “You’re telling him to come outside and sit.”

So she went to the desk and said, “Why is my husband sitting out here when his PSA is 15?” Then the nurse said, “I’ll go check with the doctor. The doctor said, “That’s okay. I’ll see him next month.” My mother said, “Thank you.” And she told the desk, “No need to put him down for another appointment.” And when she went next door to tell another doctor what had happened, they told her, “We’ve already scheduled him for someone else.”

My mother says my father was in remission for a long time. She says now men don’t know what to do, “because doctors are now saying you don’t need to be going through no PSA. It’s because of the false-positive reading. There are people who have had their breast removed because they have had a false positive, and they’re saying the same thing now about women and the breast.”

She says the way they approach prostate cancer now is different than how they approached it when my father was going through his experiences with it. After it was determined that there was nothing else the doctors could do for my father, it was decided that he would spend his final days at home with the assistance from hospice services. A lot of the family history speculates that my father’s father and his grandfather could have also had prostate cancer.

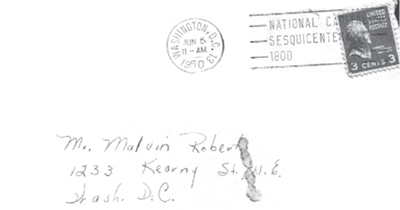

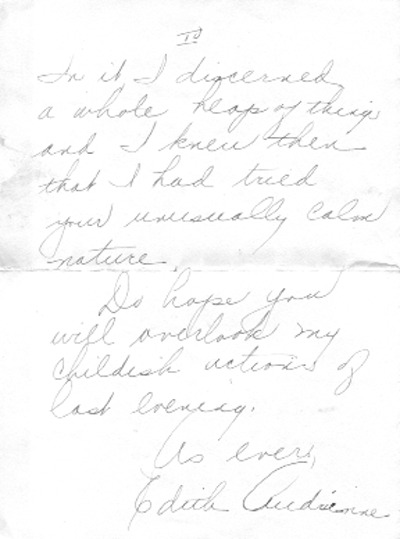

My mother wrote this letter to my father on June 4, 1950. From the tone of the letter, my mother was apologizing for something she said or did in relation to her behavior when they were last together.

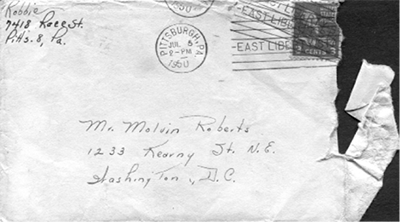

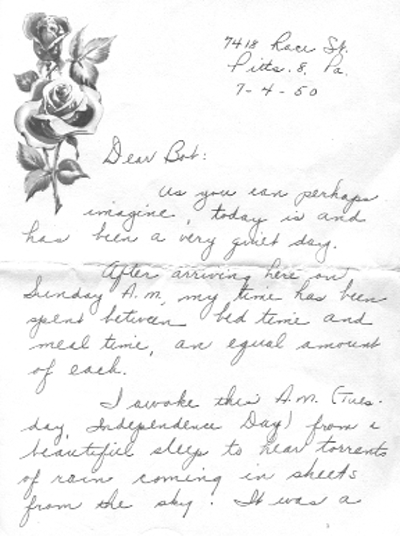

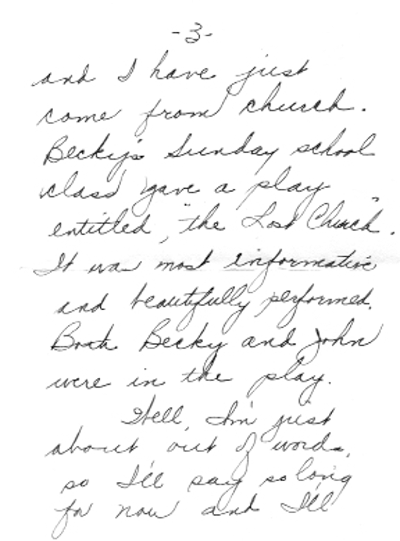

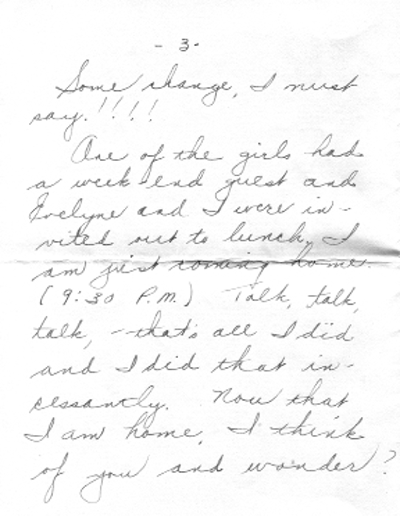

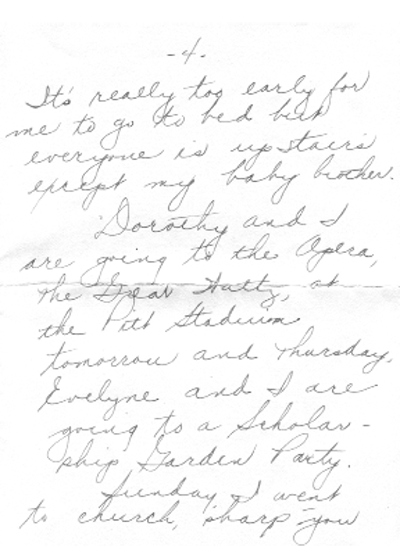

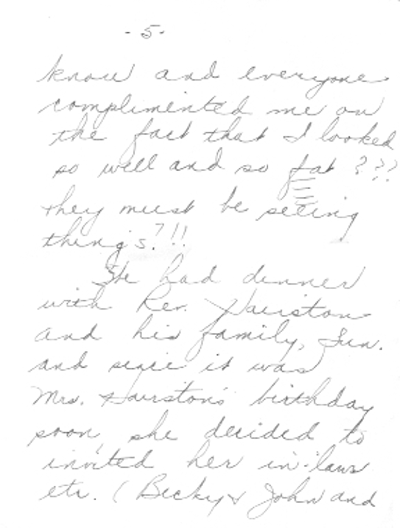

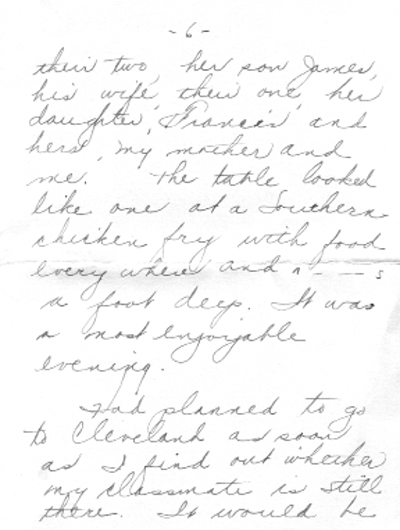

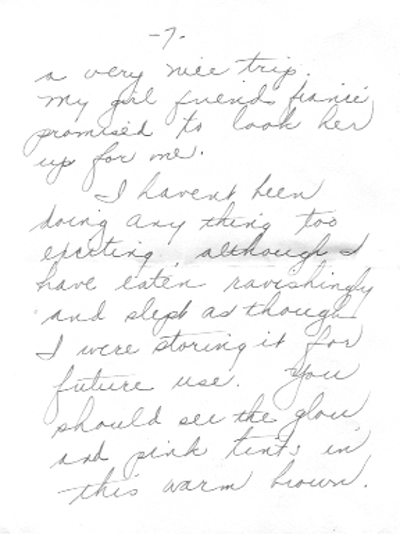

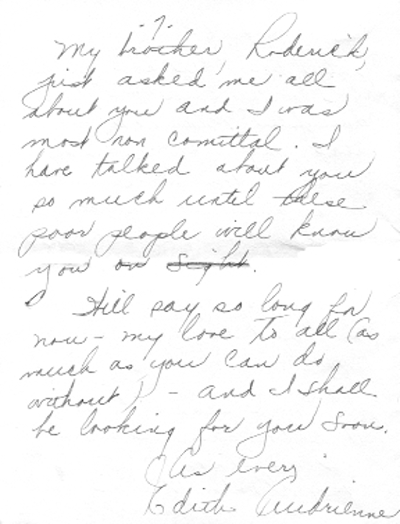

My mother wrote this letter to my father on July 4, 1950. This letter reads like a journal, as she gives a detailed account of what she had been doing since she last saw him.

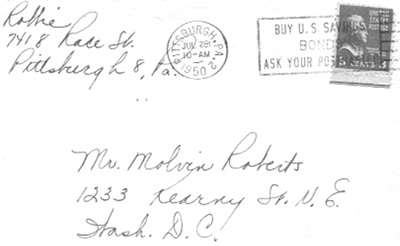

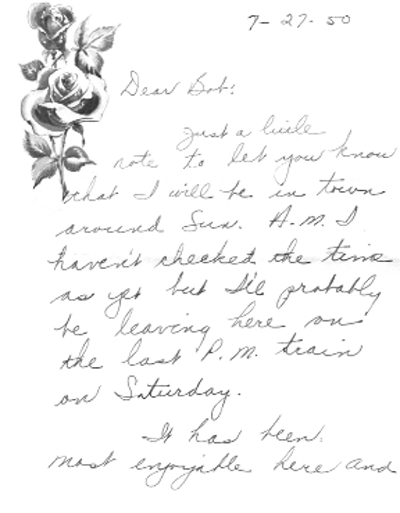

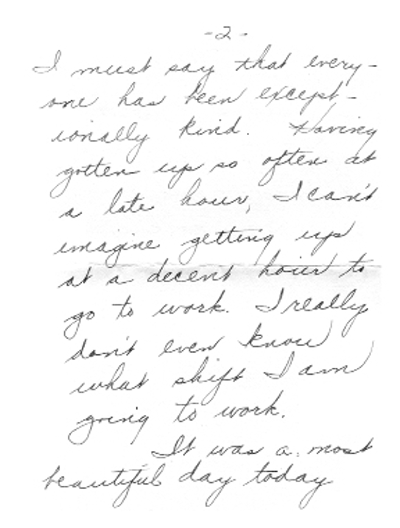

My mother wrote this letter to my father on July 27, 1950. She wrote to inform him that she would be in town soon and gave him a quick update on her life.

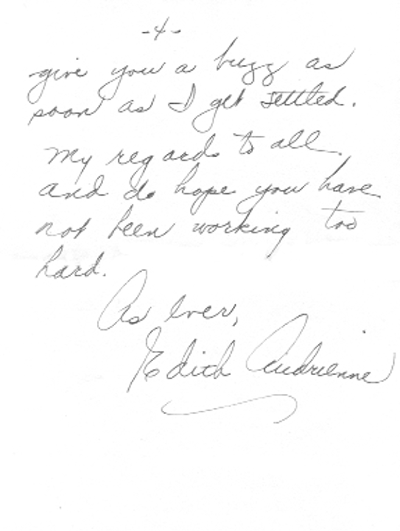

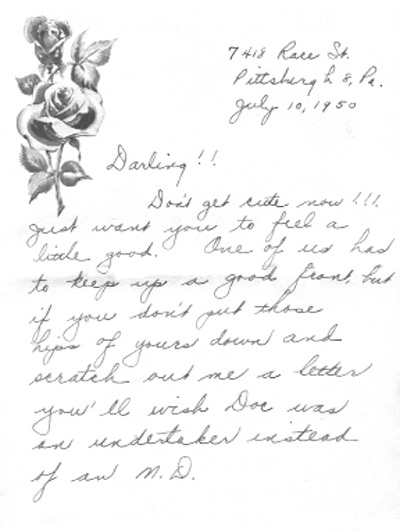

This letter, to my father from my mother was written on July 10, 1950. She gingerly encourages my father to write her back and once again gave him a detailed account on what she had been doing since she last wrote him.

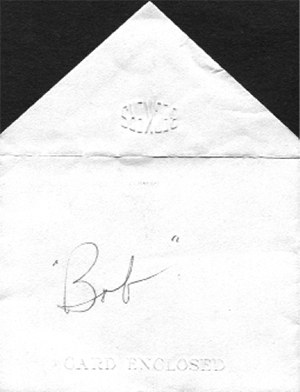

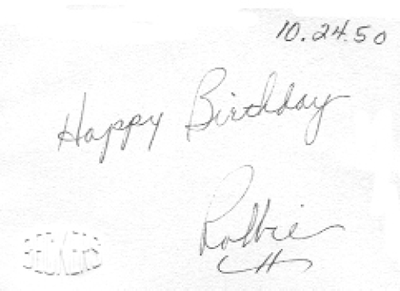

This little card was attached to a gift my mother gave my father on the day of his birthday on October 24, 1950. At the time, my father was thirty-seven years old.

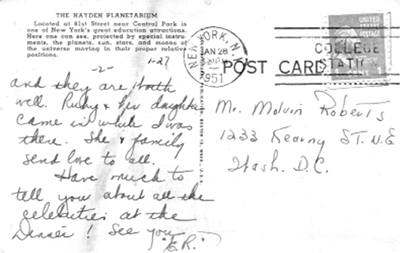

This postcard was given to my father from my mother in 1951. She had been visiting New York, New York, at the time.

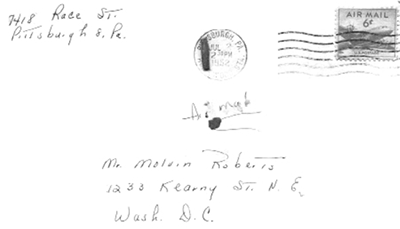

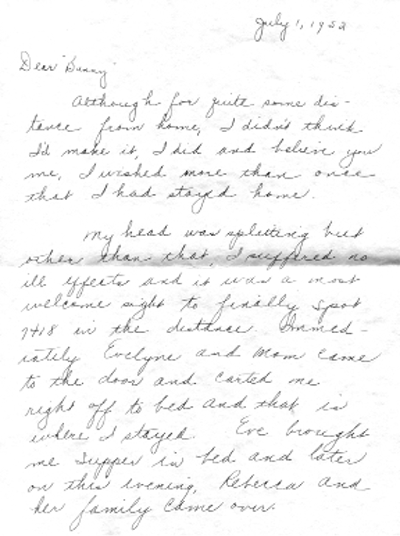

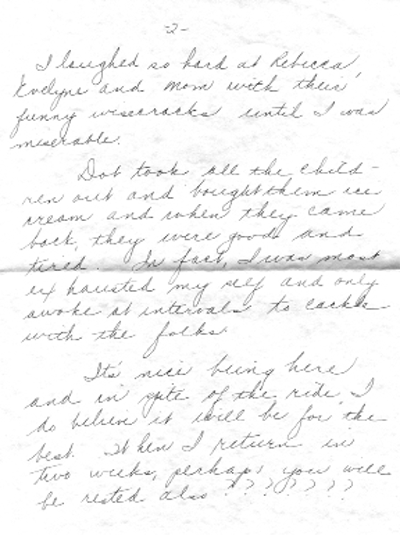

This letter was written to my father from my mother on July 1952. My mother wrote of how ill she was upon her initial arrival home and how she also looked forward into being reunited with him.

My father (Horace Sr.) and mother (Edith) were married on February 6, 1955, on Benning Road, NE, Washington, DC. My father was forty years old, and my mother was twenty-nine years old. At the time, their apartment rent was $60 a month.

As my father slips the ring on my mother’s hand, my father’s brother Jim (James Eliron/JE) was the best man, while my mother’s sister Dorothy was her maid of honor.

Rev. Earl L. Harrison, the minister of the Shiloh Baptist Church at the time, conducted the marriage ceremony. Standing with my parents next to my father is his brother Jim (James Eliron/JE).

After saying, “I do,” my father and mother made a toast and prepare to cut the wedding cake.

My parents hand in hand slow and steady, cutting the delicious wedding cake.

Standing for a group picture after the wedding ceremony from left to right is my father’s brother Henry, his brother Russell, my mother’s brother Roderick, my father’s mother Sallie Jane, my father Horace Sr., my mother Edith, my mother’s mother Minnie, my mother’s sister Dorothy, and my father’s brother Jim (James Eliron/JE).

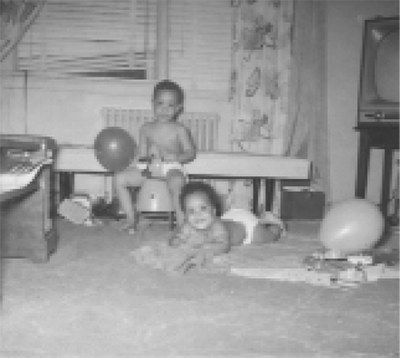

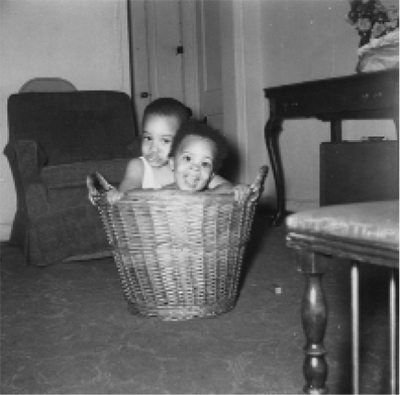

My brother Horace Jr. sitting on his riding toy, while I lie on the floor at our first apartment on Benning Road, NE in Washington, DC.

We had a small apartment and not many toys. However, my brother and I often enjoyed playing inside tight places, like this laundry basket.

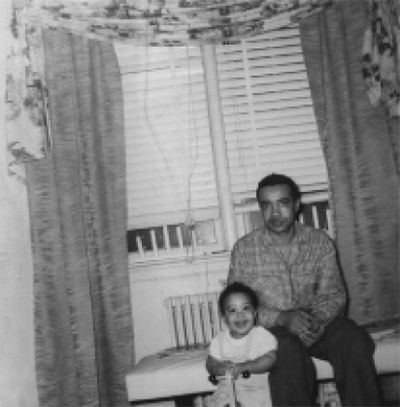

My father and I are happily posing after he taught me how to operate my ride-on toy.

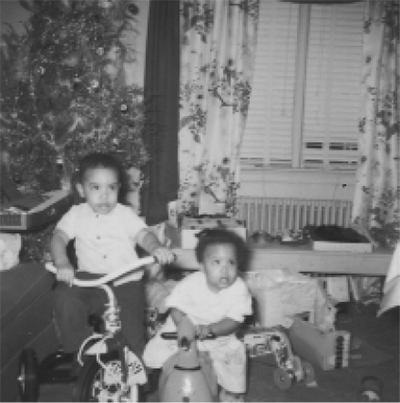

Here I am sitting on the right of my brother Horace Jr., enjoying my second Christmas in our apartment. Here I’m sitting on my first ride-on toy.

My brother is sitting here on my father’s mother Sallie Jane’s lap in our apartment.

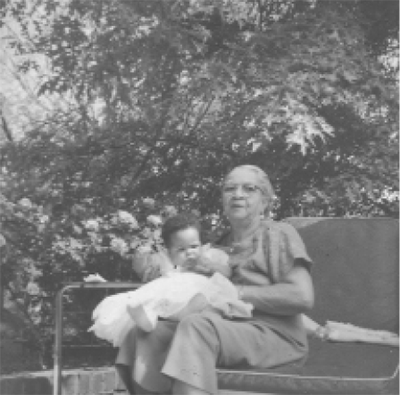

My father’s mother Sallie Jane is holding me on her lap after joining my parents at my baby dedication ceremony at the Shiloh Baptist Church.

My parents purchased their first and only house on Channing Street in NE Washington, DC, in 1959, when I was three years old. The cost of the house was $19,000.

This is one of the family cars my father purchased that lasted for many, many years.

My father is here holding me at one of the many cookouts we would attend in the neighborhood.

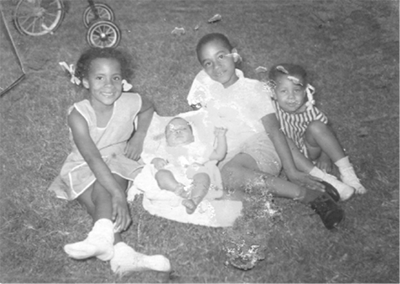

This photo was taken in the back yard of my family home on Channing Street, NE in the summer of 1963 when my baby brother Jamie (James Knox, named after my father’s father) was born. Joining me are my brother Horace Jr. on the right of Jamie and my sister Marilynn next to Horace Jr.

My brothers and sister and I standing together at the zoo in 1972, while my father takes the photo.

My brothers and sister and I posing for my father in 1979 at the University of Pittsburgh after receiving my Bachelor of Science Degree.

My brothers and sister and I older and wiser and all grown up, but still standing tall in 2001.

My father had a green thumb and worked hard planting and growing vegetables every year.

Just like his father James K. Roberts, my father was also a master gardener.

My father grew so many vegetables that he started growing them in the alley behind our house.

My father and mother posing together on May 1979 after my graduation from the University of Pittsburgh.

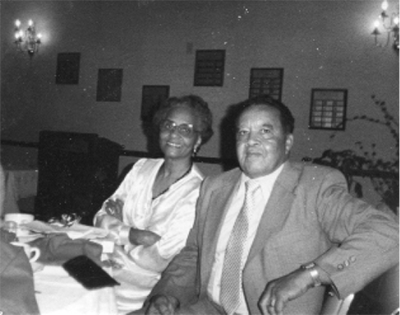

My father and mother attending one of the many affairs they attended each year.

My parents were members of numerous organizations, and they were active dues-paying members in all of them.

When my parents were not going to church or attending one of their organizations, resting at home with the family was well appreciated.

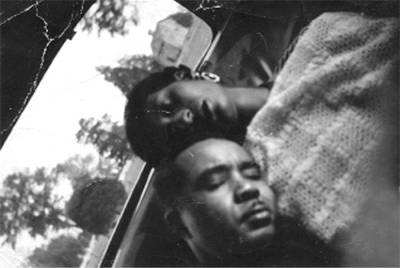

My father and mother are here in Haines Point in Washington, DC, taking a nap in my father’s car before they were married.

My parents are here again taking a nap many years later after enjoying a delicious family dinner at my home.

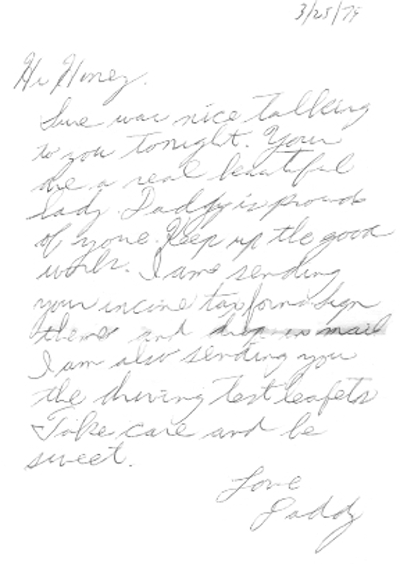

When I was away at college, this is a copy of the letter my father sent to me on March 2, 1979. Included in this letter were income tax forms I had to sign and return to him.

Here I am at the wedding reception my parents had for me and my husband. I met my husband Jeff (Thomas Jeffrey) in the spring of 1978 in Pittsburgh while I was attending the University of Pittsburgh. The next year we were married in Decatur, Georgia, on December 25, 1979. Jeff and I were married months after I graduated from the University of Pittsburgh. At that time, I was twenty-three years old, and Jeff was twenty-five. We were married by the Justice of the Peace in his brother John’s living room. After getting married, we attended a wrestling match at the Omni Coliseum in Atlanta, Georgia.

My father and husband Jeff at my first child’s (Khiana) Halloween party at my parent’s house in 1983.

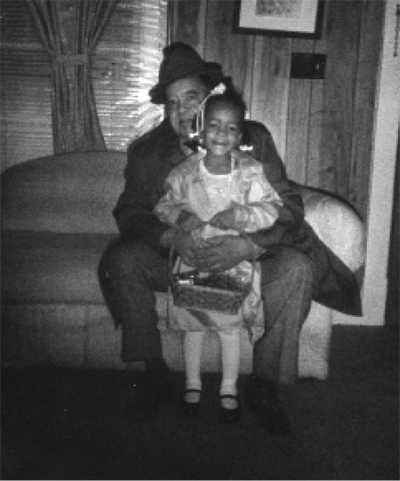

My father with my third child (Noteisha), after church on Easter Sunday.

At home resting with my father and husband Jeff, with Baby Shabreia and Noteisha.

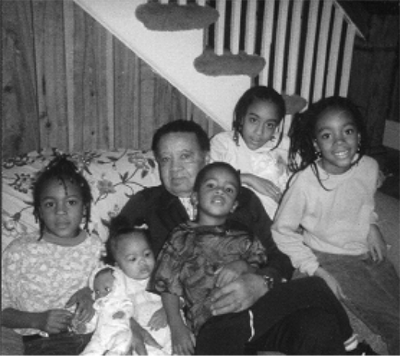

My father and five of my seven children, Noteisha, Shabreia, Montell, Khiana, and Lanika.

My father taking a nap after a long day working in the garden.

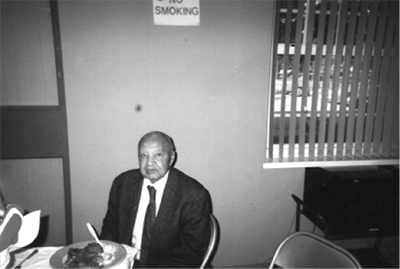

My father at one of his many community service events.

My father relaxing and enjoying the company of his sister Ethel and brother Henry.

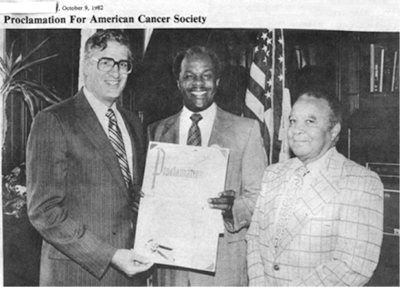

My father and other participants celebrating success with the American Cancer Society. My father was an active member for many years.

My father supporting Walter Fauntroy at a community affair.

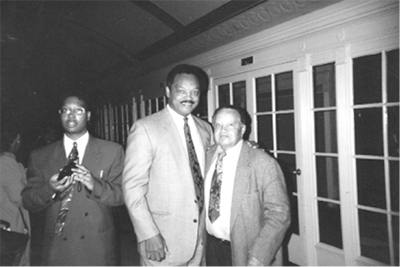

My father posing with Jesse Jackson at a fund raising event.

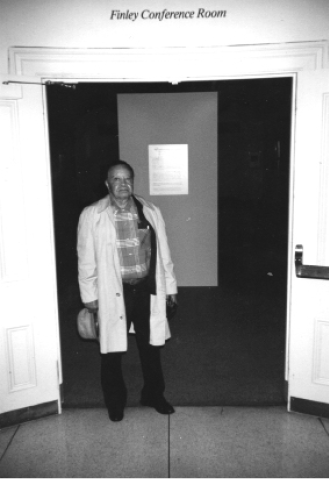

My father after attending another community event located in the Finley Conference Room.

My father standing with Reverend Henry C. Gregory III, pastor of the Shiloh Baptist Church, and Walter F. Fauntroy, pastor of the New Bethel Baptist Church,

Civil Rights activist and delegate from District of Columbia.

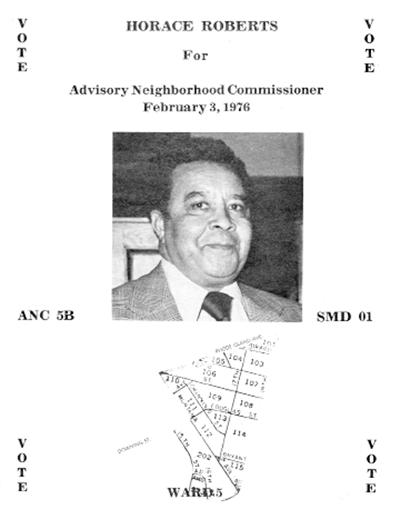

My father was very community and civic minded. He was the Ward V ANC (Advisory Neighborhood Commissioner) for many years.

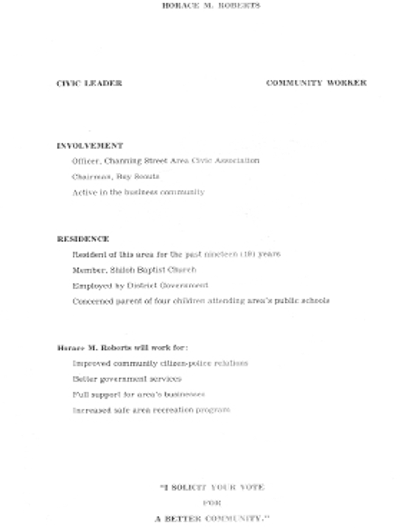

This was the resume my father submitted when running for the ANC position.

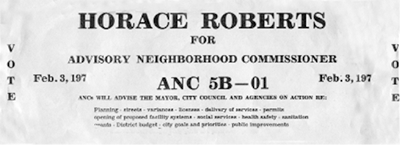

This was a copy of the announcement my father used to publicize the ANC position he was running for on February 3, 1976.

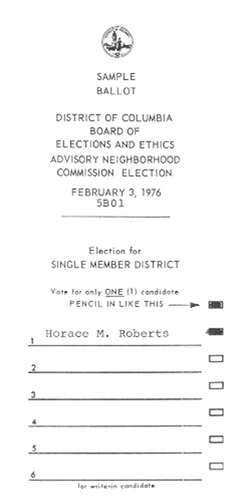

This was a copy of the sample ballot that my father used to advertize his candidacy for ANC.

My father was an active member of the American Cancer Society for many years. He is pictured here with Mayor Marion Barry and Dr. Stewart, the newly elected president of the American Cancer Society in 1982.

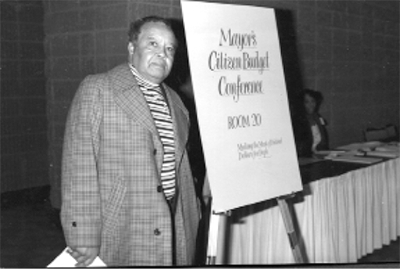

My father attended and participated in the mayor’s Citizen Budget Conference for Mayor Marion Barry.

My father was a dedicated supporter of Marion Barry. Here he hosts a Bar-B-Que at our home in honor of his re-election for mayor of Washington, D.C.

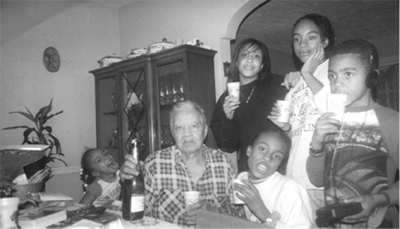

My father enjoyed spending time with family. Every Thanksgiving, we spent this time together at my parent’s home.

My father was very active in the community. During the week, he attended many meetings and events.

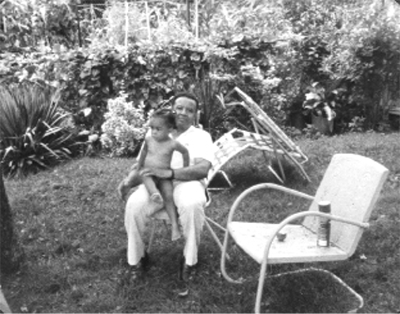

No matter how busy my father was, he always took time to be with his family. Here he holds my daughter Khiana in our backyard.

Here I am pregnant with my first child, Khiana. I’m standing beside my father at my baby shower in 1982.

My daughter Khiana was my first child and the first grandchild. She was born on my mother’s birthday, October 29. My daughter loved spending time with my father and her grandfather.

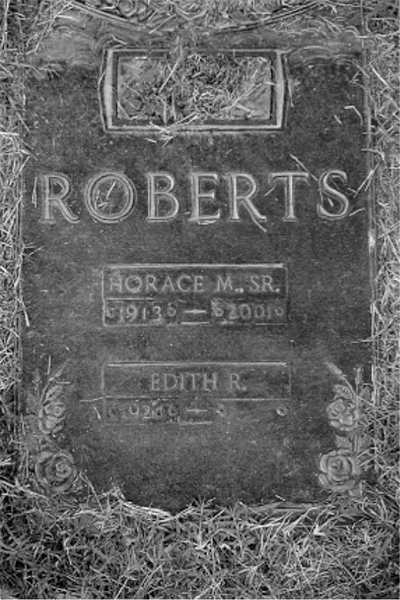

My father is standing in the Fort Lincoln Cemetery in Washington, DC. He is standing close to where his brother Henry and his wife Althea are buried in the section called Ascension (and steps away from where his gravesite will eventually be).

Enjoying another meal with my mother and father and daughters Noteisha and Lanika.

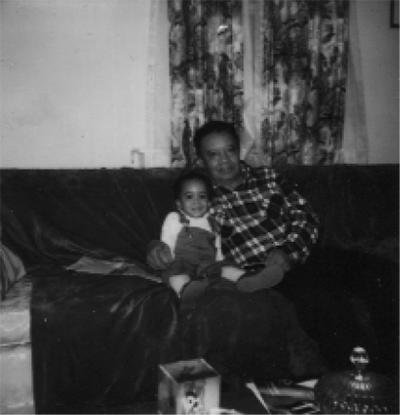

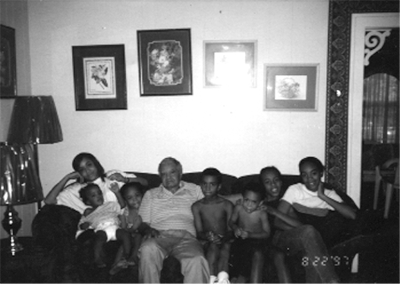

My father is sitting with all seven of my children Khiana, Juwan, Shabreia, Montell, Trevon, Noteisha, and Lanika, in the living room of my home in 1997.

Here we celebrate New Year’s Day with my father and children Shabreia, Noteisha (sitting), Khiana, Lanika, and Montell (standing).

Here my father attends my mother’s sister Dorothy’s third wedding ceremony in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

By the time this photo’s was taken, my father was getting very weak. It was beginning to get difficult for him to go up and down the stairs. He would often get dress and remain on the coach for the rest of the day until it was time for him to go upstairs to bed.

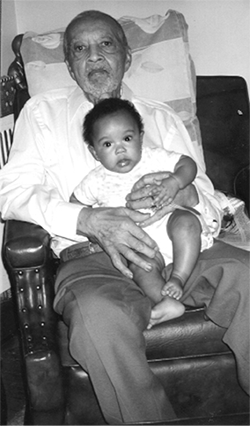

My father is shown here holding my brother Horace Jr.’s daughter Niya. My brother and his wife, Wanda, had come into town for Niya’s baby dedication ceremony at the family church, the Shiloh Baptist Church.

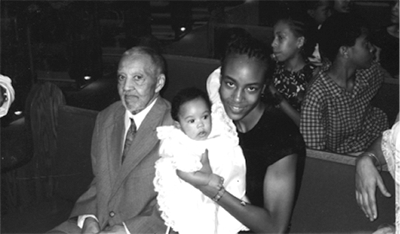

My father waited patiently for the baby dedication ceremony to begin. He waits here with my brother’s daughter Niya and my daughter Noteisha.

This photo was taken after the baby dedication, which was performed by Rev. Charles Wallace, the minister of the Shiloh Baptist Church. My father wanted to walk during the ceremony rather than use a wheelchair, even though he was very weak. This was the last time my father was out of the house and able to walk on his own. He was bedridden soon after returning home.

(Pictured here from left to right , standing in the 1st row, my sister Marilynn, daughter Khiana, son Montell, niece Ilani, nephew Jabari, son Juwan, son Trevon, daughter Shabreia, daughter Lanika and myself, Audrienne. Standing in the back row, sister-in-law Wanda, brother Horace Jr., daughter Noteisha, niece Niya, mother Edith, father Horace Sr., Rev. Dr. Wallace Charles Smith, husband Jeff/Thomas and brother James/Jamie).

My father’s cancer had spread to his bones by this time. He became weaker and weaker. Some days he would not open his eyes, while other days he would speak clearly and profoundly. Once when my husband Jeff and I were visiting, I started crying because I knew it wouldn’t be long before he was no longer with us. When I thought he was sleeping, I said, “Daddy, tell me something good.” And at that time, he opened his eyes and looked at me and said, “Stand up and live.”

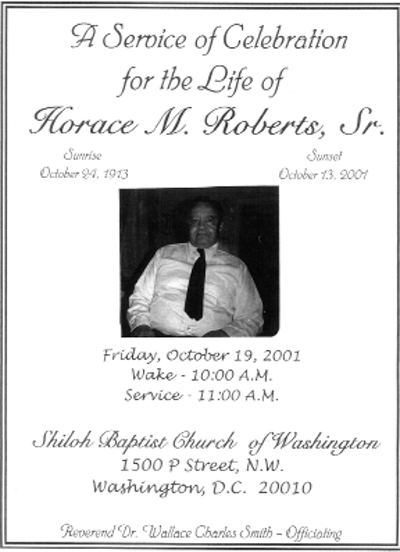

My father passed away on October 19, 2001.The day before my father passed away, he looked up and began staring at something in front of him. When I asked him what he was staring at, he said he saw men dressed in white looking at him. When I asked him if he was afraid, he sat up, looked in their direction, laid back down, and said no. Then as always, I asked him if he was going to be there for me the next day, he shook his head, meaning no. We were by his side when he took his last breath, and then he was gone.

My father was born on October 24, 1913, in Standard Shaft, Pennsylvania, and died on October 19, 2001, in his family home surrounded by those he loved. He put up a good fight to live, but his prostate cancer overpowered him in the end. There is no doubt in my heart that he knew he was loved and that he will be missed.

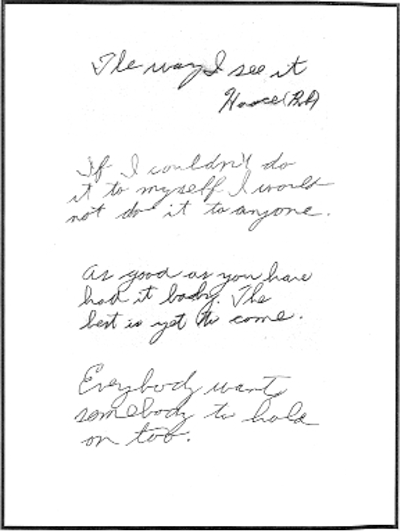

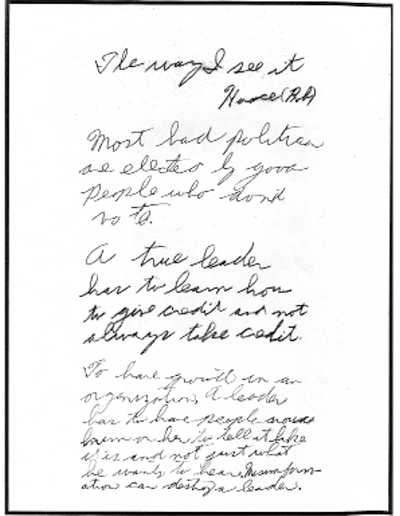

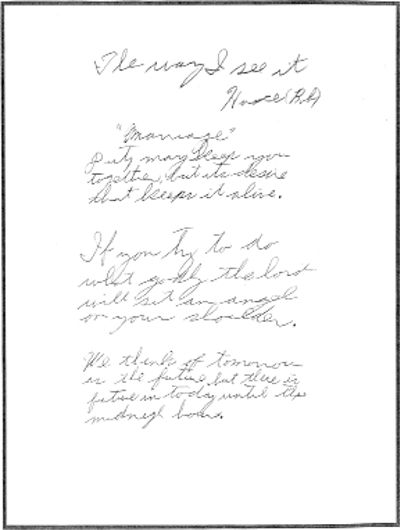

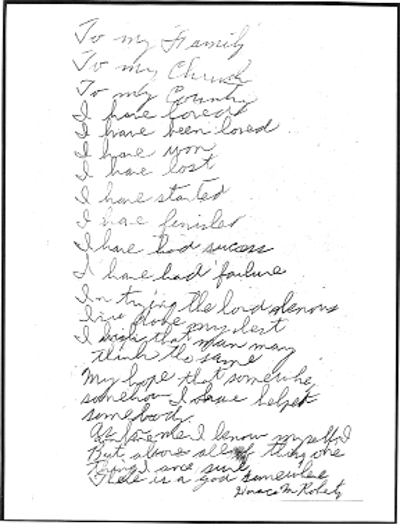

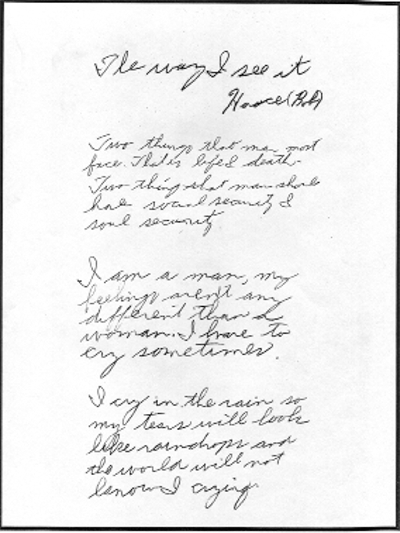

After my father’s funeral I found these words of wisdom in his belongings that he must have been writing for years.