CHAPTER ONE

Posing Basics

The Goal

The goal of any pose is to flatter the subject. The pose should appear natural to the subject. The subject should appear relaxed and comfortable. Because we are portraying a three-dimensional subject in a two-dimensional medium, we must be careful to follow some basic rules to show shape and form and to prevent distortions in the subject’s features. In the pages that follow, we’ll take a look at some simple strategies that all photographers can adapt, with every client, to take a significant step toward creating better portraits.

A good pose helps to create a sense of a third dimension in a two-dimensional image, flatters the form, and discourages distortion.

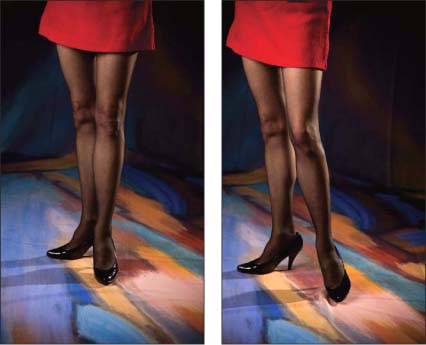

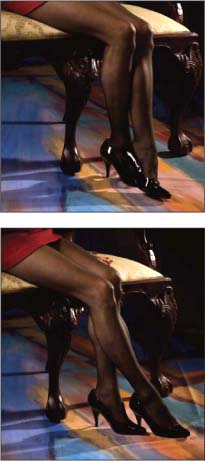

The way that the subject’s feet are posed affects the line of the whole body and, therefore, you should be sure to carefully position your client’s feet—even if you do not plan to show them in the final image. Left—This is the basic foot position for the basic pose. Right—To add a little more flow to the pose, have the subject move the front foot away from the light, then turn the knee slightly toward the light. In both of these images, the light is coming from the left. If this were a full-length image, you would see that her face was turned toward the left.

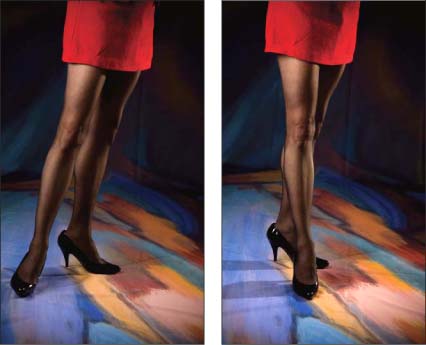

Left—Here is the basic foot position used for the feminine pose. In the feminine pose, the body is turned away from the light and the face is turned toward the light. Note that in these images, the main light was placed to the left. Right—Here, we have enhanced the lines of the feminine pose by moving the front foot closer to the light, and bending the knee away from the light.

Start with the Feet

A good pose starts with a strong foundation. When posing your subject, you must pay attention to the feet—whether or not you plan to include them within the photographic frame. In a typical pose, I will have the person stand with their weight on their back foot (the one farthest from the camera). This lowers the back shoulder and shifts the line of the hips, giving some flow to the body and creating a more dynamic, appealing line.

My friend and fellow photographer, Ralph Romaguera, has a “twosey” law. Any body part that a person has two of—e.g., eyes, hands, shoulders, feet, etc.—should be positioned at different levels. It is a good rule. When every part of the body is on the same level, the body—and the overall image—looks stagnant and boring.

Posing and Lighting

Without light, there would be no portrait. Of course, the quality of light and the way in which the body relates to the light have an important affect on the success of the portrait. Though this book is about posing, the topics of light and pose are intertwined; therefore, we’ll occasionally look at the way in which the body is posed in relation to the light.

Even before I pose the feet, I decide how I’d like the subject’s face to be turned. I usually have the face turned toward the light. When posing a male subject, I tend to turn the body toward the light as well.

“Masculine” and “Feminine” Poses

The rules of posing have been in place for centuries. There are certain strategies thought to best showcase male characteristics and others thought to suit feminine qualities. Of course, some rules are meant to be broken, and your female client may look great in a masculine pose. Always consider the mood you wish to establish in the portrait when selecting a pose for the photograph.

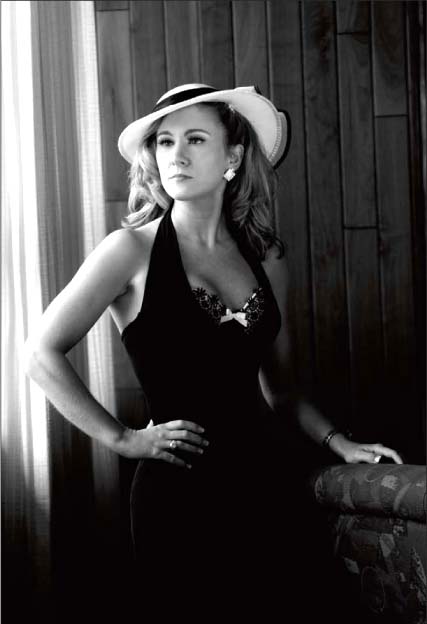

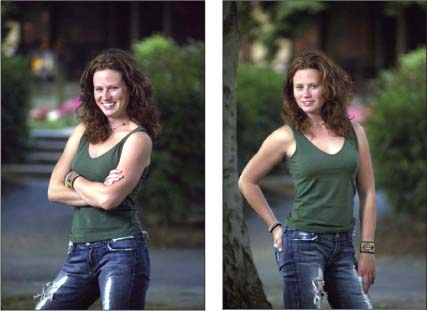

Many women look great in the masculine or basic pose (left), in which the body and face are both turned toward the light source. The feminine pose (right) plays up the S-shaped curve that heightens the undulating lines of the female form. The body is turned away from the light and the face is turned toward the light.

Above—Feminine and masculine posing applies to seated poses also. In the left photo, the bride is in the feminine pose, with her body angled away from the light and her face turned back toward it. In the right—hand image, she is shown in the masculine pose, with her face and body turned toward the light. Right—When crossing a seated subject’s ankles, I typically have her cross the front leg over the back leg so that the sole of the foot doesn’t show.

The “masculine” or “basic” pose is shown in the image on the right. In this pose, the back foot is angled toward the light. The subject’s hips and shoulders are turned toward the light. Finally, the face is turned toward the light, and the top of the head is slightly tipped toward the light. In this pose, the body takes on a C shape. Therefore, the masculine pose is sometimes called the C pose.

When posing a woman, I typically turn her body away from the light. Her back foot is positioned to point away from the light at about a 45 degree angle, and the front foot is turned more toward the camera. With her feet in this position, her hips will be angled away from the camera, and I can turn her shoulders back toward the camera and turn her face more toward the light, with her head tilted slightly toward the light. This puts the two eyes on different levels, rather than parallel to the ground.

I am trying to achieve a slight S curve to the body. A very pretty and feminine shape. For the most part, women look good great in both the S and C pose. However, men usually look best in the C pose.

The feminine and masculine (basic) posing applies to sitting poses, also. The beautiful bride on the left is in the feminine pose. Her body is turned away from the light, and her face is turned back into the light. On the right, her body and face are turned into the light.

No matter the basic pose, some other basic rules apply. Though you may have some success in posing a very slim person with their body square to the camera, more flattering images are usually created be positioning the body at an angle to the camera. Photographing a subject straight on can cause them to appear larger. Posing the hands and feet to point directly at the camera can also make those features appear distorted. We’ll cover additional dos and don’ts of posing throughout this book.

In the masculine pose, or C-shaped pose, the subject’s body and face are turned toward the light source.