Figure 1. Lucrezia Bori as Magda in La rondine’s American premiere at the Metropolitan Opera, 1928.

The Swallow and the Lark: La rondine and Viennese Operetta

MICAELA BARANELLO

In March 1914, the close-knit world of Viennese operetta received a shock: Siegmund Eibenschütz, director of the eminent Carl Theater, had reached an agreement with Giacomo Puccini for the composition of a new operetta, “a comedy about a courtesan who begins a love idyll with an innocent young man.”1 The news broke publicly in the Neues Wiener Journal’s “Behind the Curtains” column, a regular compendium of gossip. “For several days,” the columnist emphasized, “the operetta circle has been very energetically occupied with this news.”2 For this small theatrical community, an operetta by Puccini was a tantalizing prospect, but it also would have seemed an intrusion by an outsized interloper. The most surprised of all, the columnist claimed, was preeminent composer Franz Lehár—and not due to the threat of competition or even the existence of the agreement itself. Puccini and Eibenschütz’s agreement stipulated a libretto by “Dr. Willner und Reichert,” meaning Alfred Maria Willner and Heinz Reichert, two old hands in the industry, and this particular libretto had already been offered to Lehár himself two years prior (Lehár, the columnist noted, usually got first refusal). Lehár had “read it, considered it, and rejected it.”

Even at this early point, the columnist doubted that a Puccini operetta would ever come to pass, noting that “now we’re only waiting in suspense to find out if the premiere will actually take place in the Carl Theater or whether Puccini won’t ultimately decide in favor of an opera house.”3 An opera house it would be, not in Vienna, though, but in Monte Carlo, and not until 1917, in the depths of the Great War. Willner and Reichert’s libretto was translated and adapted into an Italian-language sung-through opera by Giuseppe Adami, the title transformed from the German Die Schwalbe to the Italian La rondine (both meaning The Swallow). The story of a courtesan’s attempted romance, set against an idealized backdrop of Second Empire Paris, remained. La rondine has been captured in a purgatory between opera and operetta ever since. What may sound, from one perspective, like a pedestrian operetta is also something unique among Puccini’s operas: a bittersweet, cosmopolitan romance, whose score is filled with dance rhythms, ending not with death but rather its lovers’ separation, and yet, despite this, it is still usually described as a comedy.

When La rondine finally premiered in Vienna in 1920, audiences were both mindful and suspicious of its local origins. As critic David Josef Bach wrote:

Since Viennese operettas are most easily exchanged with operas when they are at their most false, namely in their sentimentality, it seems obvious that the master of all sweetness and sentimentality, Giacomo Puccini, has now foisted himself upon an operetta text in which he has embedded above all products of the Viennese industry.4

Bach goes on to argue that despite Puccini’s technical brilliance, La rondine’s libretto—and its operetta heritage—imposed a distancing, mannered barrier between the events and their telling: “Dr. Willner and Reichert certainly gave him a tear-softened operetta libretto. Operetta, though silenced, is at work: passionate melody is reduced to gestures toward passion, tender sweetness to sentimentality.”5 The vivid passion that the Viennese considered Puccini’s greatest, and most Italian, asset was muted, the generically confused text made more awkward by being filtered through multiple translations (from German to Italian and back to German again—except for the Viennese premiere’s leading tenor, who sang Ruggero in Italian).6

The shadow operetta of La rondine allowed—perhaps, when he soured on the contract, forced—Puccini to step outside his customary practices. The story of courtesan Magda’s brief departure from her wealthy patron Rambaldo and romance with naïve young Ruggero is not easily given a role in a teleological narrative or a location within any particular national tradition. It is intimate, modest, and largely bereft of dramatic tension. Like its wartime 1917 premiere in Monte Carlo, it seems to exist outside of its place in history. For many scholars, La rondine is a failed experiment, primarily due to a mix of musical styles that were simultaneously derivative and faddish. Puccini’s early Viennese biographer Richard Specht found it “feeble from beginning to end. […] There is not a single bar in it that does not echo something he has said before,” and describes the story as warmed-over La bohème and Manon Lescaut.7 Arnaldo Fraccaroli agreed, adding that it was not only second-rate Puccini, it was also faddish rather than classic, with “banal and overused self-repetitions of situations and episodes characteristic of fashionable scale-models of light opera.”8 Julian Budden faulted its originality and dramatic gravity, calling it a “Traviata from which all the larger issues have been banished.”9 After multiple revisions of the opera—three versions in total—Puccini was himself inclined to agree, referring to La rondine as “this pig of an opera.”10

What La rondine is usually not called is an operetta. For all the explicative weight its origins have been made to bear, they have rarely been explored in detail. La rondine is inevitably compared to Die Fledermaus (one of the few operettas familiar to modern audiences) in its characters and some plot events, its many waltzes are noted, and the third act’s convoluted melodrama is considered at odds with the lightness of the first two.11 But the milieu, characters, and plot of La rondine are not derived from the nineteenth-century Fledermaus but rather are highly typical of work of twentieth-century “Silver Age” Viennese operetta in general and librettos by Alfred Maria Willner in particular.12 The rumor that the libretto was originally intended as a straightforward operetta for Lehár is, though, entirely plausible. Yet Willner and Reichert have often been discounted; Michele Girardi, for example, refers to them in terms of “influence” rather than authorship.13 William Ashbrook argues that the libretto is Adami’s, not Willner and Reichert’s.14 Primary responsibility for this disavowal surely goes to Puccini himself, who shortly after the Monte Carlo premiere attested to La rondine’s Italian credentials and gave no credit to Willner and Reichert. This repudiation, however, was prompted not by aesthetic confusion but rather political pressure.

Puccini’s renunciation is nonetheless convenient, normalizing a problem work by assigning La rondine an Italian lineage. His equivocations have been given too much credit, however, particularly given the wartime circumstances in which they were made. It is the work of Willner and Reichert, and the world of operetta, that gives La rondine its otherworldly air, its lack of national affiliation, and, in that time of war, even its Second Empire nostalgia. Examining La rondine as a hybrid operetta reveals many of these features as standard features. Yet a hybrid of opera and operetta also defies conventional analytic frameworks. In the first section of this essay, I will trace La rondine’s history as operetta, placing it in the context of Viennese work of its time. I then will examine how and why this history has been concealed.

In 1923, Puccini told journalist Desiderius Papp, again in the Neues Wiener Journal: “I never think to seek out operetta theaters in Italy. But when in Vienna, I never neglect to see two or three performances.”15 For many Viennese, a fusion of local operetta and Italian opera seemed only natural. According to many histories of operetta, Vienna’s proximity to Italy and Viennese audiences’ fondness for Italian opera marked, for better or worse, an important stage in the genre’s development. Alluding to the long reign of Italian opera in Vienna, Lehár credited Viennese audiences with a “love for aria, which often places great demands on the singers’ vocal abilities.”16 For Puccini, operetta seems to have been emblematic of the importance of music in the city’s cultural life.17

Work on La rondine began in 1913, when Puccini was in Vienna for the local premiere of La fanciulla del West. As usual, he went to see some operettas. The Fremden-Blatt chronicled Puccini’s theatrical adventures in Vienna, a series of performances in the company of Ricordi agent Carlo Clausetti. These included Paul Ottenheimer’s short-lived Der arme Millionär (The Poor Millionaire) at the Johann Strauss Theater and Lehár’s Die ideale Gattin (The Ideal Wife) at the Theater an der Wien. Puccini, the paper noted, had a “particular predilection” for Lehár’s music.18 The two were personal friends; Lehár often attended Puccini’s premieres and entertained him when he was in Vienna. Stefan Frey argues that the importance of this relationship has been discounted by many Puccini scholars, even though much of the evidence is drawn from promotional press features.19 Such publicity was mutually beneficial: Lehár profited from Puccini’s operatic credentials and Puccini could avail himself of Lehár’s local popularity.

During his stay in Vienna, Puccini attended, possibly at Lehár’s invitation, a party hosted by Siegmund Eibenschütz at a Heuriger (vineyard inn). There, Eibenschütz proposed that Puccini write an operetta for his theater, which would not only premiere there but also be published by Eibenschütz’s own firm of Eibenschütz & Berté. The sum offered was enormous: 200,000 Kronen ($40,500).20 In comparison, leading operetta composer Leo Fall’s 1916 contract for a new work with the rival Theater an der Wien included a guarantee of only 30,000 Kronen.21

Some kind of informal agreement was reached, yet Puccini’s enthusiasm quickly cooled. Upon receiving the proposed subject in December—whose authorship remains unknown—he wrote to his Viennese agent, Angelo Eisner:

The subject you sent me doesn’t suit me at all. It’s the usual crude and banal operetta, with the usual contrast between Orient and Occident, balls and occasions for dancing, without character studies, without originality, and finally without interest (the most serious thing). So? An operetta I will never do: comic opera, yes, like Rosenkavalier but funnier and more organic. Or if they want a lyric opera, not large but interesting and varied, nothing even close to operetta, I would do it more willingly and it would be more seemly for me. So the subject sent to me is definitely discarded.22

In this letter, Puccini seems to realize what he has committed to and does not like the idea at all. His description of the “usual” Viennese operetta is, for 1913, entirely accurate. East-West contrast had been a staple since Johann Strauss’s 1881 Der Zigeunerbaron, and generalized character types, to be filled in by celebrity actors, were the order of the day.

Puccini received a second subject in the spring, this one by Willner and Reichert, which he accepted.23 Die Schwalbe, the future La rondine, was not a model of originality either. According to “Behind the Curtains,” it was originally the work of Willner and Robert Bodanzky, one of the most prominent librettist duos in operetta.24 Their previous work included three major operettas for Lehár: first the enormously successful Der Graf von Luxemburg (The Count of Luxembourg, 1909), a marriage comedy about Parisian bohemians; then the ambitious, operatic Zigeunerliebe (Gypsy Love, 1910); and, finally, Eva (Das Fabrikmädel) (Eva [The Factory Girl]), which premiered at the Theater an der Wien on 24 November 1911. Eva had been a successful but controversial piece: a sentimental fairy tale of a naïve, orphaned factory worker who falls in love with her cynical Parisian boss.25 The operetta was heartily criticized, not only for its staging of a brief workers’ revolt in Act 2, but for the perceived implausibility of its plot, which combined a gritty factory setting with a Cinderella story.26

Die Schwalbe, then, was plausibly written as a follow-up to Eva and would have been presented to Lehár at or around Eva’s premiere. The Theater an der Wien’s intendant, Wilhelm Karczag, had reportedly gone so far as to buy the rights to Die Schwalbe for his publishing company for Lehár’s use and, after Lehár’s rejection, was obliged to ask for a refund.27 Die Schwalbe would have been a fitting continuation of the Willner-Bodanzky-Lehár partnership. The story—a jaded courtesan falls in love with a naïve boy from the country—inverts Eva’s pairing of a simple girl with a nightlife-addled man. This time it is the woman who is urban and world-weary while the man is a young romantic. The gender reversal is not simple: in both cases the man occupies the more socially stable position. The naïve Ruggero is a respectable member of the provincial bourgeoisie while courtesan Magda has an even more dubious status than orphan Eva. But the underlying mismatch is similar.28 (The name of Eva’s secondary male lead, Prunelles, also strongly recalls La rondine’s secondary lead, Prunier.)29

The sad ending of Puccini’s opera might seem the work’s least operettalike feature, and indeed unhappy endings were rare in operetta before the 1920s. Yet there is one prominent example and it is Willner and Bodanzky’s Zigeunerliebe. The ending, extended dream sequence, wild dramatic landscapes, and “Gypsy passion” of Zigeunerliebe, as well as the thin social realism of Eva’s factory setting, were all part of Lehár and Willner’s mission to make operetta more than a frivolous entertainment and stake a claim to art. The irony didn’t escape Viennese critics’ notice, and is evident in Bach’s review of La rondine, quoted above: even as Puccini looked at operetta as a chance to escape into light music, Lehár and Willner were working to transform operetta into something more Puccini-like. The Neue Freie Presse specifically referred to Eva’s score as “in the style of Puccini or a post-Wagnerian music drama,” and it and Zigeunerliebe were routinely referred to as operas.30 After Die Schwalbe, Willner and Bodanzky would continue on this path with Endlich allein, a dramatic Alpine operetta again written for Lehár (1915). And after Puccini’s death, Lehár was even proposed as a candidate to complete Turandot, presumably due to his Chinese-themed operetta Die gelbe Jacke (The Yellow Jacket, 1923), the first version of Das Land des Lächelns (The Land of Smiles, 1929).31

La rondine is a much more conventional Silver Age operetta than Eva. Especially since Richard Heuberger’s 1898 hit operetta Der Opernball (The Opera Ball), Paris had stood for sex and modernity in a way Vienna did not.32 The demimonde of the Second Empire in particular coincides with operetta’s generic origins. The characters of La rondine correspond to the Fach system used in operetta, and not usually in opera: one leading couple, Magda and Ruggero (lyric soprano and tenor or light baritone); a lighter-voiced, younger “second couple,” Lisette and Prunier (soubrette and comic tenor); and various minor supporting roles. Other elements reference operatic precedents: although the bohemian atmosphere of the nightclub Bullier recalls Willner’s earlier operetta for Lehár, Der Graf von Luxemburg, the busy ensemble scene complete with flower sellers and drinking students is an obvious nod toward La bohème. Similarly, the plot of a courtesan seeking true love unmistakably echoes Verdi’s La traviata. Magda’s patron, Rambaldo, recalls Geronte of Puccini’s Manon Lescaut, and Ruggero echoes Des Grieux. As many have noted, Lisette’s masquerade in Magda’s clothing for a night on the town recalls Act 2 of Die Fledermaus. For a Viennese operetta such lack of originality was not a deficit: popular elements were habitually recycled for years, if not decades. Canny pacing, jokes, and well-placed musical numbers were more important than formal or thematic originality.33 Even an innovator like Willner or Victor Léon relied on tried-and-true formulas to make their work legible as operetta.

Both Julian Budden and Michele Girardi have proposed another inspiration for La rondine—Massenet’s opera Sapho (1896). Sapho also concerns a provincial man “who falls in love at first sight with a worldly woman. […] She [Sapho, the equivalent of Magda] flees with the unwitting Jean, living with him for a year in idyllic happiness in the suburbs of Paris until the young man learns the truth from two of the woman’s ex-lovers.”34 The similarities are striking. Yet, while scholars have largely been concerned with Puccini’s awareness of Sapho, Willner and Reichert’s knowledge seems far more salient. Sapho had no Viennese performance history at the time of La rondine’s composition, but this does not mean Willner did not know it; operetta composers habitually drew from a wide range of preexisting sources, often without credit or with sources actively concealed (in order to avoid paying royalties), the more obscure the better.35 French subjects were so popular that when describing the process of composing a libretto, Willner said that he began with a concept, either from a French source or by inventing one himself.36 It seems more likely that if Willner knew Sapho, it was through Massenet’s source, a novella by Alphonse Daudet dating from 1884.37 Sapho’s influence on La rondine is impossible to prove or disprove, but the similarity is nonetheless profoundly ironic: Alphonse Daudet’s son, Léon Daudet, would become La rondine’s most vociferous critic.

Willner’s approach to Die Schwalbe does not seem to have differed from his working process for any other of his librettos. Even Giuseppe Adami’s Italianized version is for the most part an utterly typical Silver Age piece—sweet, wistful, and gently comic, and largely lacking in dramatic tension. Set by a conventional operetta composer for the ensemble of an operetta theater, it could be cast in five minutes. It lacks the class conflict, aristocrats, and farce of a nineteenth-century Golden Age operetta, and its romance and sincerity mark it as a twentieth-century work.

Despite Puccini’s evident enthusiasm for Silver Age operetta, his interest in Die Schwalbe quickly cooled. He wrote to Eisner on 26 May, only a few months after accepting the commission, that he was “not terribly pleased” with the libretto.38 That summer he began to adapt it into more conventional operatic form with the assistance of Giuseppe Adami. It is evident that he never intended to write a real operetta: “Like Leoncavallo!! […] I couldn’t manage to do it like him even if I tried,” he wrote dismissively to Eisner.39 The point at which Puccini stopped writing an operetta and started writing an opera remains unclear. William Ashbrook claims that he never had any intention of writing the former, citing the letter to Eisner and a much later letter from Willner criticizing Adami’s work.40 The commission obviously specified an operetta, however, implying that this difference of purpose had not been fully clarified by Eisner, perhaps opportunely. Nevertheless, it seems strange that Puccini would sign a contract so cavalierly—placing himself in such a tight bind, as the history of Rondine attests, that not even a war could prevent its fulfillment.

Other evidence suggests that the Carl Theater management was convinced they had commissioned an operetta: on 21 March 1914, Musical America reported that Andreas Dippel, German tenor and erstwhile joint manager of the Metropolitan Opera, had bought the American and Canadian rights.41 Dippel had recently left a position as manager of the Chicago-Philadelphia Grand Opera and one condition of his resignation was a non-compete clause. Forbidden to produce opera, he founded the Dippel Opera Comique Company in New York. Dippel’s acquisition of La rondine for this company—presumably via Eibenschütz & Berté, who held the American rights—strongly suggests that the contract had indeed stipulated that Puccini would compose an operetta.42

Contrary to Ashbrook’s interpretation, Willner’s letter to Puccini suggests that the eventual work was actually rather close to his own original scenario. The letter objects to relatively small-scale issues of construction, most having to do with etiquette and character motivations, none of which imply that Adami made major, wholesale changes.43 If anything, Willner’s letter is strong evidence that Adami’s interventions were anything but drastic, and many of the points are minor. For example, Lisette is judged as far too forward for a maid—Willner says that in the original, it was Prunier who described the wonders of Parisian nightlife. The description itself, however, can be found in Willner’s original. Puccini, it is clear, set an operetta libretto.

The composer’s waning enthusiasm was only the beginning of La rondine’s problems. As with most plans made in early 1914, the future of the project was thrown into disarray by the outbreak of the Great War. On 23 May 1915, Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary, and a premiere across enemy lines was impossible. Ricordi had no interest in publishing La rondine and Puccini signed an agreement for the Italian publishing rights with rival Sonzogno—his first and only work placed with another publishing house. After protracted negotiations with the initiating Viennese publishers, some of which took place in person with Berté in Switzerland, the premiere of La rondine was relocated to Monaco, neutral territory and an oasis of leisure seemingly perfectly suited to La rondine’s delicate charm.

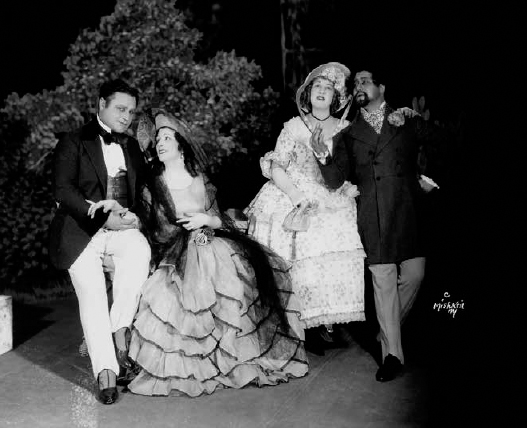

Figure 2. Beniamino Gigli (Ruggero), Lucrezia Bori (Magda), Editha Fleischer (Lisette), and Armand Tokatyan (Prunier) in Act 2 of La rondine, Metropolitan Opera, 1928.

“The Rondine Affair”

The Opéra de Monte-Carlo was a fitting location for La rondine’s premiere. Since 1892 the Opéra had been run by the enterprising Raoul Gunsbourg, a French-Romanian Jew whose career had begun in St. Petersburg, where he had founded an operetta theater before running the private theater of Tsar Alexander III. Gunsbourg’s own cosmopolitanism was ideally suited to the internationalism of Monte Carlo and was in turn reflected in his eclectic, adventurous programming.44 For La rondine, the intimate Second Empire theater located in neutral territory was practically and symbolically apt. In the midst of the war Monaco’s relative isolation and peace made it one of the few places where a sad, nostalgic visit to an imperial past might seem wistful rather than blind. For Puccini and his Austrian publishers, it was an attractive compromise.45

Although Monaco made the premiere possible, the contract between Puccini and Eibenschütz & Berté still crossed enemy lines. French criticism of the premiere’s financial terms—that the performances were enriching the Viennese enemy—would prove decisive for the reception of the work and for Puccini’s own stance toward it. Though this controversy has received little attention from scholars, it is a key stage in the erasure of operetta from La rondine, as well as an illustration of how far the work had strayed from wartime norms. The instigator of the “Rondine Affair” was Léon Daudet, one of the editors of the far-right newspaper L’Action française.46 As a political movement, the archconservative Action Française was never influential; its plotted coups d’état to restore the monarchy were fatally—and, considering the group’s name, ironically—undermined by indecision.47 Yet as propagandists the group was successful. Puccini had already been briefly a subject for L’Action française’s wrath when he failed to sign a letter protesting the bombing of Rheims.48

Being Romanian and Jewish, Raoul Gunsbourg was an obvious target for a movement founded during the Dreyfus Affair. In a series of front-page essays that appeared some weeks before the premiere of La rondine, Daudet condemned Monte Carlo as a hotbed of German espionage and called Gunsbourg not only a métèque (a derogatory term for a foreigner) but also German (probably really named Gunzburg) and a spy.49 His cosmopolitanism, a boon for his opera house, now made him a convenient object of suspicion. On 25 March, only a few days before the premiere, Daudet reported that the commission for La rondine came from the Viennese, neglecting to specify that the contract originated before the war began. He then described with considerable embroidery Swiss negotiations between Gunsbourg, Puccini, Sonzogno, and Weinberger (another Viennese publisher, which he confuses with Eibenschütz & Berté) to bring La rondine to Monaco. The very existence of these negotiations, he said, was proof of commerce with the enemy. As additional evidence, he cited a 1916 interview with Puccini from the magazine Noi e il mondo, in which the composer despaired over his “contrat malheureux” (unfortunate contract). Gunsbourg’s plans to donate the premiere’s box office take to wounded Allied soldiers was an ignominy worthy only of a traitor, Daudet claimed.50 Most important, Daudet implored Puccini to renounce any influence Willner and Reichert may have had on the libretto and proclaim it as solely the work of Adami. Daudet’s condemnations of the Jewish Gunsbourg, Willner, and Reichert had an anti-Semitic subtext.51

The implication that the premiere constituted treason and would financially benefit the enemy was a grievous charge against Puccini. A planned onetime performance at the Opéra-Comique in Paris was canceled, a turn of events for which Daudet took credit (later denied by Puccini). Daudet added a litany of other claims: that while in Switzerland, Sonzogno had acquired for Gunsbourg a number of Viennese operas and operettas to be performed as the work of Italian composers with the idea of laundering the money back to Vienna; that Gunsbourg was leading tours to Berlin for the purposes of selling information.

Daudet’s accusations were not a matter of aesthetics; nor would they have been possible without La rondine’s internationalism and hybridity. The terms by which Daudet attacked Gunsbourg and Puccini are familiar, and telling: Gunsbourg is effeminate—a “danseuse”—more international than nationalist. La rondine’s lack of clear national credentials made it inappropriate wartime entertainment.

Puccini’s vociferous, thorough, and sweeping responses to Daudet’s charges betray just how perturbed he was by them. He first gave a statement to Parisian critics, printed in the “Courrier des théâtres” in Le Figaro on 29 March and on 1 April alongside the reviews of the premiere in Le Matin. Puccini proclaimed that he wrote La rondine in 1912 on an “Italian libretto by the Italian poet Giuseppe Adami,” that the opera was to be premiered in Vienna, and that despite his best attempts he could not fully escape his obligation.52 On 10 April he published a more extended essay in the Corriere della sera. This account contains a somewhat more truthful description of the operetta’s origins, though Puccini still insists that he rejected Willner and Reichert’s libretto in favor of what is implied to be a completely different one by Adami, writing that “thus, the libretto was born of a continuous and assiduous collaboration between Adami and me, to which Messrs. Willner and Reichert remained extraneous.”53 Willner and Reichert, on the other side of the front, were discarded. His defense of his patriotism had required the renunciation of his Viennese collaborators, a denial that erases La rondine’s early history and leaves concealed the importance of Willner and Reichert’s work.

Doretta and Prolepsis

After the war, when La rondine made its belated Viennese premiere in the autumn of 1920, Willner and Reichert returned, translating Adami’s libretto back into German and evidently working with Puccini on the revisions. When Eibenschütz & Berté finally published the opera, it was in this second version.54 Now it was Adami who had vanished, his name nowhere to be found on the printed score. The publishers also took the operetta-like liberty of dividing Puccini’s score into numbers, something not found in German-language editions of other Puccini operas, none of which were, of course, published by Eibenschütz & Berté.55 The vestigial operetta structure is evident: the act begins with an ensemble introduction, then contains entrance songs for both the leading lady and man, Ruggero/Roger’s romance “Paris, ja das ist die Stadt” being a new addition to the score;56 followed by Magda’s waltz song, “Nur Geld, immer Geld” in the German version. The list is too short (and sections are accordingly too long) for an operetta table of contents, but the same organizational principle is at work.

One of La rondine’s most operetta-like features is the diegetic song “Che il bel sogno di Doretta,” found early in the opera, begun by Prunier as an incomplete song, then completed by Magda. Such narrative “story number” songs had been a standard feature of Silver Age operetta ever since the massive success of The Merry Widow’s “Vilja-Lied” in 1905. Usually lyrical and strophic, the songs relate a fairy-tale parallel to the operetta’s plot, giving depth to the characters’ feelings and implying that they are participating in an archetypal scheme. “Che il bel sogno di Doretta” is unusual, however, in that it appears not at the customary place at the beginning of Act 2 but rather near the start of Act 1, presenting a situation that is not reflective but prophetic. Puccini’s setting begins with Prunier’s incomplete song set in fragmentary fashion—Prunier playing incantatory arpeggios on an onstage piano, introducing one motive, but offering few indications of tempo or affect. Prunier introduces the fictional Doretta, a girl who turns down a romance with a king. After singing only a few lines of regular four-measure phrases, Prunier breaks off and begins speaking at “Ah! Creatura! Dolce incanto!” (Ah, child! Sweet enchantment!); his sentiments seem to betray as much enchantment with his own words as with the imaginary Doretta. A solo violin playing under Prunier’s words seems to hint at the song’s completion, with a high-pitched, conjunct, and long-breathed theme, particularly compared to the opening theme’s disjunct, short phrases. But the violin’s theme, a voice from outside the song’s diegetic space, does not yet have words to give it semantic meaning.

Magda takes up Prunier’s challenge to finish the song. She provides an explanation for Doretta’s rejection of her royal suitor: a genuine romance with a student, sung to the same music of Prunier’s opening. But she also completes the song by finding words to sing the violin’s theme. Beginning on a high A marked dolcissimo, Magda echoes Prunier’s enchantment in more specific terms: “Folle amore! Folle ebbrezza!” (Mad love! Mad intoxication!). She takes what existed for Prunier as pure sentiment and moves it gradually into dramatic reality. Her vocal line extends the theme from its previous appearance, finally transitioning back into non-diegetic space as the three-note love theme from the opera’s opening returns in the orchestra, linking Doretta’s love to the opera’s larger plot.

The equation of Magda and Doretta is explicit: first in the use of the love motive, then later in Prunier’s reference to Magda as “the real Doretta.”57 Shortly after this number, Magda reminisces to her friends Bianca, Yvette, and Suzy an incident initially identical to the one she allegorized in the song “Ore dolci e divine di lieta baraonda,” (Sweet and divine hours of happy chaos; rehearsal number 23), now given some temporal specificity—the evening Magda ran away from her aunt—and a location in the restaurant Bullier, as well as dramatic details (she and her mysterious lovers write their names on their table). But now her romance has an end point: she heard a distant “strange music” and a voice warning her that her romance would end in tears. Unlike the first story, this time the music is not explicitly diegetic. It is, however, a waltz, and the score’s most extended exercise in popular music up to this point, giving the “strange music” described by Magda a self-referential quality.

The entrance of Magda’s future suitor, Ruggero, follows this number and could hardly be more portentous. Magda is concealed behind a screen, having her fortune read by Prunier. He speculates “like the swallow,” she may fly to a “land of dreams” and love.58 Simultaneously, Ruggero chats with Rambaldo, their dialogue trivial in comparison but its significance obvious—even heavy-handed. Like his song, the fortune Prunier provides Magda lacks an ending. Magda, however, knows her fate, having already given it away in her waltz. Acts 2 and 3 largely consist of the actions that have already been foretold, right up to Magda writing her (assumed) name on a table at Bullier. Magda’s and Ruggero’s predicted separation eventually follows.

The opera’s plot, therefore, is proposed as a fantasy or a dream, begun by a poet and completed by a courtesan. As Rambaldo suggests before “Doretta,” the subject of love is “un po’ appassito” (a bit passé), but simultaneously, as Magda replies to him, “sempre nuovo” (always new). Magda’s romance does not arise naturally but is adopted temporarily and selfconsciously as an “argomento,” a plot, one whose moves she knows even as she performs them. Magda’s actions are as if preordained, as if having already occurred. This predestined nature of the plot gives the entire romance a tinge of fateful despair—something more complex and melancholy than what Budden described as a “Traviata from which all larger issues are banished.”59 As Viennese critic David Josef Bach described, the dictates of operetta structure and the diegetic elements of the music confer a degree of remove from the events as depicted. For La rondine, operetta’s formulas are not a straightjacket, but the source of its strange inevitability.

The Swallow Returns to Vienna

The Vienna premiere of Die Schwalbe also marked the first outing of a reworked third act, the second of three versions. This was an act that had long been troublesome; in November 1914, Puccini wrote to Adami that “the third act makes me suffer horribly … perhaps La rondine will remain two acts and a postlude.” The third act, however, seems indispensable, since it contains the most serious action of the opera: Ruggero’s discovery of Magda’s past and their parting. The mechanics of this separation, however, were never completely worked out to Puccini’s satisfaction and play out very differently in each of the opera’s three versions. That Magda and Ruggero part in each version gives the opera its poignancy: one way or another, the bourgeois morality of Ruggero’s family will not permit their relationship to last. That Adami, Willner, Reichert, and Puccini found it surprisingly difficult to maneuver their separation—prompted variably by an anonymous letter, an injunction from Rambaldo, or a revelation by Prunier and Lisette—perhaps indicates how the work fails to conform to any generic pattern.

In comparison, operetta was freewheeling and even, at the time, forward-looking, even beyond Eva’s pairing of industrialist and orphan. One of the biggest successes of the war period, Emmerich Kálmán’s Die Csárdásfürstin (The Gypsy Princess), presents a couple with a very similar problem: the aristocratic Edwin is engaged to a Tingeltangldame (nightclub singer) named Sylva. By the end of the operetta, the social mores that kept the two apart are revealed to be hypocritical, because Edwin’s mother had, early in her life, also spent time as a Tingeltangldame. Stephen Beller argues that this kind of progressivism, particularly in regard to class, was typical of wartime operetta, “stressing not only its ability to divert from life’s realities but also its emancipatory and even assimilatory potential.”60 La rondine’s affirmation of nineteenth-century ideals of virtue and morality is comparatively anachronistic; it is part of what makes the opera old-fashioned and, for 1917, tone deaf.

If this were a typical Silver Age operetta, a discussion of the third act would need to begin at the end of the second—which would end with a denouement in which a secret is dramatically revealed, leading to a crisis and cliffhanger, the so-called tragic second act finale. In Die Csárdásfürstin, for example, Sylva’s sordid professional life is revealed in front of Edwin’s aristocratic family. The ending of La rondine’s second act is comparatively placid. A distant, anonymous woman sings an ominous warning: “Mi vuoi dir chi sei tu? … Nell’amor non fidar” (Do you want to tell me who you are? … Do not trust love) as Magda and Ruggero declare their love. But it is easy to imagine what a more typical second act finale would be: Magda’s true identity is revealed to Ruggero in public at Bullier, possibly by Rambaldo, or in anger by Lisette or Prunier. Ruggero condemns Magda publicly (like Alfredo in La traviata), recapitulates one of his declarations of love in bitter irony, and the chorus loudly expresses its confusion and shock. Then, in Act 3, the situation would be harmlessly resolved: Ruggero and Magda would reunite and together live happily ever after.

Instead, La rondine moves this revelation and accompanying denouement to the end of the opera, where there is no space for resolution. The usual operetta structure is present but drawn out and, finally, truncated. The opera has been frequently criticized for its low stakes, but perhaps this seemingly trivial ending could be better understood as an operetta Act 2 finale in search of its final resolution. Willner’s letter to Puccini reveals the original Act 3: no letter from Ruggero’s mother, but rather a dramatic scene in which Ruggero confronts—and, presumably, condemns—Magda in a “virile and dramatic” fashion, ending with Prunier speaking to Magda “to raise her up from her disaster.”61 Though more heated, Puccini’s three versions all lead to the same result: Magda’s return to her courtesan status quo. Magda’s romance evaporates as if it had never happened at all, the proof that “Che il bel sogno di Doretta” was, in fact, nothing more than a dream.

Figure 3. Set design for Act 3 by Joseph Urban, Metropolitan Opera, 1928.

The Lark

In the waning days of the war, slightly after La rondine’s premiere, Franz Lehár embarked on another Willner and Reichert libretto, this one titled Wo die Lerche singt (Where the Lark Sings). Whereas the swallow had sung in a nostalgic, urban Paris, the lark belonged to the Hungarian countryside. The protagonist, the suggestively named Margit, makes the opposite journey from Magda: a brief and unsuccessful idyll in the city. A young farm girl, Margit is betrothed to a neighbor but lured by a visiting artist, Sándor, to Budapest, to have her portrait painted. There Margit embarks on a romance with Sándor and tries and fails to become a sophisticate. When Sándor’s portrait of Margit wins a prize, he realizes he was only in love with her image, and leaves her for a more suitable and cosmopolitan woman. Margit is relieved to return to her country home and former fiancé.62

Lerche is “freely adapted” from Charlotte Birch-Pfeiffer’s 1847 novel Dorf und Stadt (Village and City). Its similarities to La rondine are self-evident, yet much has changed. Margit, the provincial innocent, momentarily seeks the excitement of big city life, but after a brief romance finds only infidelity and homesickness. In La rondine, the city is a place of pleasure and beauty, in Lerche it is responsible for Margit’s alienation. The score is defined not by the urban commercial music of La rondine but rather by pastiche Hungarian folksongs and dances. Even as Lerche played in various urban theaters—first in Budapest, then in Vienna, then around the world—it presented a romantic, pastoral vision. For the audience’s members, many of whom may have made their own Margit-like migration, the story was only too personal, particularly when performed amid the wreckage of the war, a kind of Habsburg Oklahoma! In contrast, La rondine would have been impossibly distant for a Viennese audience during the war. If La rondine celebrates sophistication, internationalism, and romance, Lerche exalts fidelity, (Hungarian) patriotism, and simplicity. Lerche was a canny choice for its time, a tribute to the virtues of the common peasant for a homesick audience.

In 1919, Puccini was in Vienna in preparation for the premiere of Il trittico, and probably saw Wo die Lerche singt. The Neues Wiener Journal printed what claimed to be an effusive letter he sent to Lehár. Puccini wrote, “I saw your exquisite new operetta Wo die Lerche singt and can only say, ‘bravo, master!’ Oh, what memories of the days in Vienna in 1913! I will come back with new music, return with a new work.”63 Lerche, like Rondine, cast Puccini back into the happier days before the war. Margit, after her traumatic modern adventure, returned to an intact prelapsarian countryside. Magda’s journey from a world of glamorous commerce to provincial romance is similarly temporary; like Margit’s groom, Rambaldo welcomes her back. For Puccini, the flight from opera to operetta was equally brief. However incompatible operetta might have seemed, it nonetheless cast a long shadow. As Puccini struggled to reconcile the conventions and expectations of a “Viennese product” with his own poetics, so have subsequent listeners puzzled over La rondine’s carefree melancholy. La rondine may never fit in, but its own strange history reveals fault lines between genres, national schools, and even war and peace. That history remains integral to its enduring charm.

1. This chapter is an expansion of an earlier essay, “Puccini’s Crossover Dalliance,” New York Times, 5 January 2013. My thanks to James Oestreich and Zachary Woolfe for their support.

2. “Hinter den Kulissen. Der Puccini-Rummel,” Neues Wiener Journal, 21 March 1914.

3. After this note of skepticism, the columnist turned his attention to the next pressing issue, a lawsuit between the Theater an der Wien and Lehár regarding the production of the latter’s latest operetta, Endlich allein.

4. David Josef Bach, “Puccinis ‘Schwalbe,’” Arbeiter-Zeitung, 10 October 1920.

5. Ibid.

6. Bach even claims that the Viennese premiere was translated from Italian to French and then to German. There is no evidence that Willner and Reichert, who wrote the original libretto as well as the translation, were working from a French version, but it is possible.

7. Richard Specht, Giacomo Puccini: The Man, His Life, His Works, trans. Catherine Alison Phillips (New York: Knopf, 1933), 213.

8. Arnaldo Fraccaroli, La vita di Giacomo Puccini (Milan: Ricordi, 1925), 192.

9. Julian Budden, Puccini: His Life and Works (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 392.

10. The first version is the one most commonly performed today. The phrase “questa porca opera Rondine” is in a letter from Puccini to Riccardo Schnabl, 8 October 1922, in Eugenio Gara, ed., Carteggi pucciniani (Milan: Ricordi, 1958), 529.

11. See, for example Budden, Puccini: His Life and Works, and John Champagne’s recent analysis. Champagne considers the Rondine’s much-revised third act to reflect the difficulty of marrying melodrama to operetta, but I argue that these two modes are far from diametrically opposed. John Champagne, Italian Masculinity as Queer Melodrama: Caravaggio, Puccini, Contemporary Cinema (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), 115–46.

12. The Silver Age of Viennese operetta began with the premiere of Die lustige Witwe (The Merry Widow) in 1905 and stretched to the genre’s decline in the early 1930s. Silver Age works are more cosmopolitan and serious than their nineteenth-century Golden Age predecessors. The Silver Age’s generation of composers was led by Lehár, Oscar Straus, and Emmerich Kálmán. For more on the conceptualization of the Silver Age, see Micaela Baranello, “Die lustige Witwe and the Creation of the Silver Age of Viennese Operetta,” Cambridge Opera Journal 26/2 (July 2014): 175–202. Willner is occasionally identified as “Arthur Maria” rather than “Alfred Maria.” The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek has identified “Alfred” as the standard form.

13. Michele Girardi, Puccini: His International Art, trans. Laura Basini (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), 340.

14. William Ashbrook, “La rondine,” in The Puccini Companion, ed. William Weaver and Simonetta Puccini (New York: W. W. Norton, 1994), 260.

15. Desiderius Papp, “Bei Giacomo Puccini,” Neues Wiener Journal, 11 May 1923. During this visit he saw Lehár’s Die gelbe Jacke (the first version of Das Land des Lächelns) and Libellentanz, as well as Jean Gilbert’s Katja, die Tänzerin.

16. Franz Lehár, “Die Zukunft der Operette,” Die Wage, 10 January 1903.

17. In 1921, the Neues Wiener Journal printed a letter claiming to be from Puccini to Lehár in which Puccini exalted Vienna as “that city where music resonates in the soul of every person and even inanimate objects seem to have rhythmic life.” “Puccinis letzte Grüße an Wien,” Neues Wiener Journal, 7 December 1924.

18. Puccini also attended the Intime Theater, a small venue in the Nestroy-Platz that performed one-act plays because, the report specifies, “he is looking for subjects for an evening of three one-act operas,” the future Il trittico. Since Puccini’s German was, by most accounts, rudimentary, it perhaps should not be surprising that he did not find anything. The report goes on: “The first act of the triptych will be tragic, the second lyrical, the third comic; the tragic act will be based on Houppelande [The Cloak, the future Il tabarro], which he discovered in a suburban Parisian theater.” “Aus der Theaterwelt,” Fremden-Blatt, 19 October 1913.

19. Stefan Frey, Was sagt ihr zu diesem Erfolg: Franz Lehár und die Unterhaltungsmusik des 20. Jahrhunderts (Frankfurt: Insel, 1999), 141–42.

20. These details of origin were provided by Eibenschütz’s son Karl to Michael Kaye. Budden specifies without source that Lehár introduced Puccini to Eibenschütz. Michael Kaye, The Unknown Puccini (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987), 193; Julian Budden, Puccini: His Life and Works, 333. Later Puccini claimed that the fee was 250,000 Kronen ($50,650). Exchange rate of $0.2026 in 1912 is from U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce, Division of Statistical Research, Handbook of Foreign Currency and Exchange, by James R. Mood (Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Service, 1930), 13.

21. Both Fall and Puccini also received a cut of the box office proceeds. The Fall contract is for Die Rose von Stambul (The Rose of Stambul), which was one of the biggest successes of the decade and ultimately proved very lucrative. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Musiksammlung F88 Leo Fall, Folder 283.

22. Puccini to Eisner, 14 December 1913, in Gara, Carteggi pucciniani, 417.

23. Willner described his compositional process in 1905: first a concept, then a plot outline with moments for diegetic music, followed by a full draft, then a go-through by the theater management to adjust the distribution of the musical numbers among their cast. “Wie entsteht eine Operette? Eine Rundfrage,” Neues Wiener Journal, 11 June 1905.

24. Viennese operettas were customarily written by pairs of writers, one responsible for the overall planning and spoken dialogue and the other for the verse of the song texts. Alfred Maria Willner (1859–1929) fulfilled the former role and the replacement of Bodanzky with Heinz Reichert (1877–1940), described speculatively by the Neues Wiener Journal, would not be significant for the work’s larger plan.

25. The uproar over Eva had largely centered around a scene in which the factory workers revolt in defense of Eva’s virtue, a scene that some critics saw as threateningly similar to several real workers’ protests in Vienna around the same time.

26. See Frey, Was sagt ihr zu diesem Erfolg, 141–45.

27. Both Eibenschütz and Berté of the Carl Theater and Karczag of the Theater an der Wien operated publishing firms in conjunction with their Viennese theaters. This enabled them to develop new operettas for their stage and then further profit from royalties as other theaters produced the work, as well as sell sheet music and arrangements to salon orchestras and to the general public.

28. They are called Madeleine and Roger in the German version; I use the Italian names for consistency.

29. Giuseppe Adami had even translated Eva for its Italian-language premiere in Milan, a translation that was subsequently published by Sonzogno, the eventual Italian publisher of La rondine. A. M. Willner, Robert Bodanzky, and Franz Lehár, Eva: Operetta in tre atti, trans. Giuseppe Adami (Milan: Casa Musicale Sonzogno, 1911).

30. “Franz Lehars Operette ‘Eva,’” Neue Freie Presse, 25 November 1911.

31. Frey, Was sagt ihr zu diesem Erfolg, 188–93. The relationship is also chronicled in Jürgen Leukel, “Puccini und Lehár,” Schweizerische Musikzeitung / Revue musicale suisse 122/2 (1982): 65–73.

32. After Der Opernball, Die lustige Witwe also takes place in Paris, as does Willner’s Der Graf von Luxemburg. Moritz Csáky examines the symbolism of Paris for Viennese operetta in Csáky, Ideologie der Operette und Wiener Moderne: Ein kulturhistorischer Essay zur österreichischen Identität (Vienna: Böhlau, 1996), 129.

33. Libretto design is examined in Heike Quissek, Das deutschsprachige Operettenlibretto: Figuren, Stoffe, Dramaturgie (Stuttgart: J. B. Metzler, 2012).

34. Girardi, Puccini, 339. Girardi credits Budden.

35. As a theatrical joke book put it, “Why does he write ‘from the French’ on all his librettos? So it doesn’t come out that they’re all from the English!” Alexander Engel, Vorhang auf! 250 Witze und Anekdoten vom Theater (Vienna: M. Perles, 1910), 94.

36. A. M. Willner, “Wie eine Operette entsteht? Eine Rundfrage.”

37. A play adaptation of the novel was performed in Vienna to great fanfare by the touring French actress Gabrielle Réjane at the Raimund Theater on 31 October 1899. Alphonse Daudet, Sapho: Moeurs parisiennes (Paris: Charpentier, 1884). Despite Massenet’s popularity in Vienna, Sapho was never performed at the Hofoper or the Volksoper, nor was it published in German.

38. Puccini to Eisner, 26 May 1914, in Gara, Carteggi pucciniani, 425–26.

39. Puccini to Eisner, 25 March 1914, ibid., 421–22. Cited in Girardi, Puccini, 334.

40. Ashbrook, “La rondine,” 248.

41. Musical America, 21 March 1914, cited in Kaye, The Unknown Puccini, 175. W. J. Henderson references the deal again in his review of the American premiere of Rondine, but he credits Dippel with the commission of La rondine, which, he says, was written for Broadway! W. J. Henderson, “La rondine is presented here,” The Sun (New York), 11 March 1928

42. Ashbrook places the word operetta in scare quotes without mentioning the terms of Dippel’s company; there is no evidence to believe that the Carl Theater management did not believe they would get what they were playing for.

43. The letter’s exact provenance is unclear; it was published in a program produced by the Teatro Comunale. Ashbrook quotes it in full, in “La rondine,” 260–62.

44. The company’s repertoire was extraordinarily heterogeneous. Under Gunsbourg, they performed some of the first Francophone productions of Wagner, a number of rediscoveries of works by French composers such as Lalo and Bizet, premieres of works by Massenet and Franck, a large variety of Russian operas harkening back to Gunsbourg’s St. Petersburg years, and even some of the first modern Baroque revivals of Monteverdi, Rameau, and Lully. Albert Gier, “Die 53 Spielzeiten des Raoul Gunsbourg, oder: Die Oper Monte Carlo zwischen Belle Epoque und Occupation,” in Das (Musik-)Theater in Exil und Diktatur, ed. Peter Csobádi, Gernot Gruber, and Jürgen Kühnel (Anif: Mueller-Speiser, 2005), 333; Michael Scott, “Raoul Gunsbourg and the Monte Carlo Opera,” Opera Quarterly 3/3–4 (Winter 1985): 70–78.

45. The premiere received no coverage in the Viennese press. A report in the Fremden-Blatt on 20 June 1917 even described the first Bologna performances as the world premiere.

46. Daudet was the son of Alphonse Daudet whose novella Sapho, as mentioned, may have inadvertently supplied one of La rondine’s sources, though the resemblance evidently went unnoticed.

47. Stephen Wilson, “The ‘Action Francaise’ in French Intellectual Life,” Historical Journal 12/2 (1 January 1969): 328–50; Eugen Weber, Action Française: Royalism and Reaction in Twentieth-Century France (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1962).

48. See Ashbrook, “La rondine,” 250.

49. This would be correctly spelled Günzburg; Daudet did not include an umlaut. Gunsbourg’s name came from his French father. See Léon Daudet, “Mesures contre le gaspillage: Sauf contre les Jeux de Monaco,” L’Action française, 9 February 1917; and Léon Daudet, “De Verdun à Jeux de Monaco,” L’Action française, 22 February 1917.

50. Léon Daudet, “L’Affaire de la ‘Rondine’: Gunsbourg pris la main dans le sac,” L’Action française, 25 March 1917.

51. At one point Daudet claimed that Gunsbourg conspired with a certain “Finnkalstein” to communicate intelligence to Berlin. Daudet also consistently refers to Gunsbourg as a “danseuse,” in quotation marks, simultaneously impugning his masculinity and crediting him with a dance career he never had. Léon Daudet, “Etranges Avatars du ‘danseuse’ Gunsbourg,” L’Action française, 16 February 1917.

52. “J’ai écrit La rondine en 1912 sur un livret italien du poète italien Giuseppe Adami.” The identical text appeared in Le Matin, 1 April 1917, and Le Figaro, 29 March 1917.

53. “Il libretto di Rondine nacque quindi da una continua ed assidua collaborazione tra me e l’Adami alla quale i signori Willner e Reichert rimasero estranei.” Giacomo Puccini, “Le polemiche per la Rondine,” Corriere della sera, 10 April 1917. Michael Kaye speculates that the “15,000 lire in cash to the Corriere,” referenced by Puccini in a letter to Carlo Paladini on 11 November 1919, was payment for printing this essay. Kaye, The Unknown Puccini, 187.

54. The second version had premiered in Italian in Palermo in the spring of 1920.

55. Giacomo Puccini, Dr. A. M. Willner, and Heinz Reichert, La rondine (Die Schwalbe) (Vienna: Eibenschütz & Berté, 1920), 2.

56. The music is based on Puccini’s song “Morire?”; for more on this see Kaye, The Unknown Puccini, 194–96.

57. “La Doretta della mia fantasia non si turba, ma, in verità, mi pare che vacilli quella della realtà!” (The Doretta of my imagination was not troubled, but it seems to me that the real one is yielding!).

58. “Forse, come la rondine, migrerete oltre il mare, verso un chiaro paese di sogno, verso il sole, verso l’amore.”

59. See Budden, Puccini: His Life and Works, 392.

60. Steven Beller, “The Tragic Carnival,” in European Culture in the Great War: The Arts, Entertainment, and Propaganda, 1914–1918, ed. Aviel Roshwald and Richard Stites (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 154–59.

61. Ashbrook, “La rondine,” 260–61.

62. A complete recording from a performance at the Lehár-Festival in Bad Ischl is available on CD from CPO, CPO 777 816-2 (2014).

63. Puccini to Lehár, in Neues Wiener Journal, 18 November 1919.