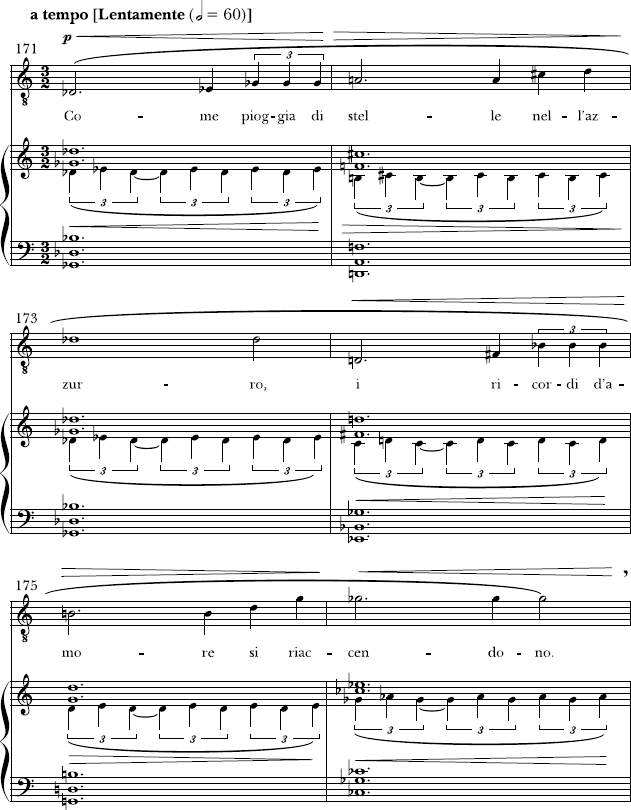

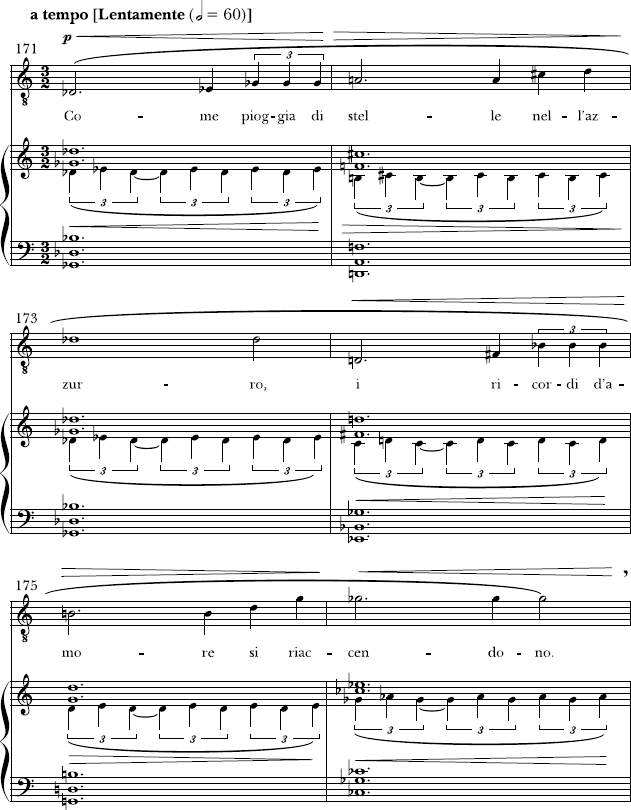

Example 1. Ennio Porrino, “Aria di Torbeno,” I Shardana (Gli uomini dei nuraghi), Act 2, mm. 171–76.

Puccini, Fascism, and the Case of Turandot

BEN EARLE

How many times did Giacomo Puccini meet Benito Mussolini? Mary Jane Phillips-Matz suggests the two men met twice, within a matter of weeks. She cites a letter from Puccini to Pietrino Malfatti—“an old friend from Torre [del Lago]”—of 1 December 1923, in which the composer mentions a meeting with the Duce that very day. This apparently followed a previous encounter in November.1 Phillips-Matz’s account contradicts the previous understanding, established in the earliest biographies, that the two men met only once.2 Perhaps her two meetings were one and the same. The date in November has never been confirmed with any precision.3 The issue may appear of slight importance. But it makes an appropriate introduction to the question of Puccini’s relationship with fascism generally. The historical record is confused, sometimes contradictory. Yet our knowledge is not so patchy that we cannot come to some provisional conclusions.

Evidence

Take Puccini’s desire to meet Mussolini in the first place. It seems clear that the impulse came from the composer rather than the politician. Phillips-Matz follows Michele Girardi in suggesting that Puccini wanted to put to Mussolini his idea for a national theater.4 But where was it to be built? Phillips-Matz suggests Viareggio; others say Rome. And was this the only idea Puccini wanted to put to the “President of the Council of Ministers”?5 Here is Vincent Seligman, elaborating on the composer’s correspondence with his mother, Sybil Seligman:

During his stay in Vienna [in October 1923] Puccini had been much impressed by the report that the Austrian Government were planning a special season of Viennese opera in London—“Wagner, Strauss, Puccini—with their own orchestra, scenery and singers—including [the soprano Maria] Jeritza.” The season never materialized, but on his return home Puccini hoped to be able to persuade the Fascist Government to take similar measures to encourage the spread of Italian music abroad. But the times were not favourable; “I don’t think Mussolini is giving a thought to Italian opera at Covent Garden,” he writes despondently. […] Shortly afterwards he met the Duce for the first and only time; but he did not succeed in making any headway. “I saw Mussolini,” he reports, “but only for a few minutes and I wasn’t able to talk much—so there wasn’t time to discuss Italian opera abroad.”6

Was the idea that an Italian National Theater would take its productions on foreign tours, as Girardi suggests? Or were these two separate projects?

Leonardo Pinzauti suggests there was a further scheme on Puccini’s mind, involving a state fund financed by the collection of royalties on works already in the public domain.7 As Fiamma Nicolodi explains, the early 1920s saw a number of attempts to persuade the Italian state to intervene on behalf of the country’s opera houses. March 1923 had seen a Congress on Lyric Theater, held in Rome and attended by Puccini’s sharpest critic, the musicologist Fausto Torrefranca, and his greatest compositional rival, Pietro Mascagni, among others. As a member of the governmental Permanent Commission for Music, Puccini would have been party to similar discussions.8 But he would go a step further and put his case to the Duce directly.

In a pamphlet, Mussolini musicista, by the journalist and musicologist Raffaele de Rensis, we find a more detailed account:

Puccini too, the gentle Puccini, […] crossed the threshold of the Office of the President. To whom he wished to set forth his impressions of and his suggestions with regard to the unhappy conditions of our musical theater and to ask for a speedy and generous intervention. Among other things, he requested the bringing into law of an old plan in respect to State’s rights to operas that have entered the public domain and the assignment of the proceeds of these rights to the lyric theater.

In a long and friendly conversation the illustrious maestro also proposed the construction of a National Theater in Rome, but the President, who had himself long dreamed of this splendid project, stressed to him the difficulty at that moment of adding to the balance sheet the many tens of millions that would be required.9

This quasi-official document stands in contradiction to Puccini’s letter to Sybil Seligman. That the meeting was far from “long” or even “friendly” is confirmed by the most detailed account, which comes from the journalist, musicologist, and friend of Puccini, Guido Marotti. The composer takes up the story himself:

When I entered the salone della Vittoria,10 I saw there, at the back, a table and two enormous globes, one on either side of it. Bent over the table, a man was writing. I remained perplexed for a few moments, then, plucking up courage, walked forward. The man, having raised his head, looked at me, and, getting to his feet, while he fixed me with two big, round, black eyes, which seemed to bore a hole through me, said brusquely:

“What do you want?”

“Nothing! … I wanted … simply to have the pleasure of meeting you.”

He held out his hand and in an affable voice:

“For myself, I am delighted to meet you!”

I had gone to see Mussolini to set forth to him certain of my ideas about the National Lyric Theater to be constructed in Rome. But he, shaking his head and rocking backwards and forwards (he had stayed on his feet), said three times:

“There’s no money for that! There’s no money for that! There’s no money for that! And to carry out Piacentini’s plan we need thirty million!”11

“If I may, Your Excellency,” I ventured, “we could, in my opinion, carry out a more modest plan, but just as—”

He didn’t let me finish:

“Either a plan as grand as that, worthy of Rome, or nothing!”

I felt his power from these few words, and thought that Italy had finally found its man … and in my confusion, I forgot even to speak to him of another thing that was … so close to my heart!12

The other “thing” was doubtless the plan for the promotion of Italian opera abroad, as Puccini told Seligman. The idea that the national theater should be built in Viareggio (which Puccini had discussed with the town’s mayor) had evidently been dropped.13 In Marotti’s account there is no talk of royalties.

Puccini had one further significant brush with fascism, but the record here is even more clouded. In a speech to parliament on the afternoon of 29 November 1924, on the occasion of Puccini’s death in Brussels earlier that same day, Mussolini claimed that “some months back” the composer had “asked for the card” of, that is, asked to join, the Partito Nazionale Fascista (PNF).14 It seems the Duce was not quite telling the truth. Even Marotti, who has no qualms about painting Puccini as a fervent fascist, tells the story differently. Puccini was “given the fascist card ad honorem.” The composer, Marotti adds, “had granitic faith in Benito Mussolini.”15 Girardi puts a further twist on the episode. In the spring of 1924, he tells us, “the officials of the Viareggio branch of the Partito Nazionale Fascista sent [Puccini] an honorary membership card, and for the sake of a quiet life he did not refuse it.”16 His source is Pinzauti, who writes:

The truth is that the Viareggio federation of the PNF made it known, around the spring of 1924, that it would like to offer [Puccini] the card “ad honorem,” and Puccini did everything he could to avoid this threat to his reputation [compromissione], even if at home his wife and friends made clear to him the inadvisability of a public refusal. And so he accepted, ever more perplexed and fearful, above all after the Matteotti crime; nor after all would the state of his health have put him in the position of being able to be more decisive in the circumstances.17

Which account are we to believe? It is not simply that they do not tally. None of these writers produces any justification for their assertions. But what does it matter if Puccini was a fascist? He was hardly alone. As Seligman puts it, with considerable hyperbole deriving from his own evident enthusiasm for the Duce, Puccini “heartily welcomed” fascism, “in common with the vast majority of his fellow-countrymen.”18 Nicolodi’s archival work has made clear that the record of Italian composers under fascism was nothing to be proud of.19 And this seems to be the point. The shame of fascism is sufficient to drive commentators not just to disbelieve, but to try to counter testimony such as that of Marotti and Seligman.

So let us lay out the evidence. Puccini’s admiration for Mussolini appears plain. Giuseppe Adami, librettist of La rondine and Il tabarro and joint librettist of Turandot, affirms that Puccini was “a fascist from the very beginning [della primissima ora],” and that “he had placed all his faith” in the Duce.20 Here is some more from Marotti:

“He is greater than Napoleon,” [Puccini] said to us one evening, “because Napoleon, you see, didn’t have so many difficulties to conquer as Mussolini. And then … well … Napoleon used canons, which is an easy means, when you are fighting battles, to overcome difficulties!”

“I am for a strong State” was his fundamental credo. “Men like Depretis, Crispi, Giolitti were to my taste because they gave orders instead of taking them.21 Now there’s Mussolini who has saved Italy from falling to pieces!” […] I don’t believe in democracy because I don’t believe in the possibility of educating the masses. It’s like trying to hold water in a wicker basket! Without a strong government headed by a man with an iron fist, like Bismarck in Germany in the past and like Mussolini in Italy now, there is always the danger that the people, who construe freedom as mere licence, will become undisciplined and wreck everything. That’s why I’m a fascist: because I hope that fascism will achieve in Italy, for the good of the country, the pre-war German national model.22

To be sure, Marotti’s account cannot be taken entirely at face value. There is a good deal of novelization here, though it should be remembered that Marotti—unlike Pinzauti, for instance—was frequently in the composer’s company. If more solid documentation is required, this too is available, especially from the period immediately following Mussolini’s “March on Rome” (28 October 1922).23 Nicolodi points out how, at the beginning of November 1922, Puccini, uniquely among Italian composers, sent a congratulatory telegram directly to the new prime minister.24 Three letters to Adami similarly testify to political enthusiasm. “The day after the March on Rome,” so the librettist tells us, “he wrote to me as follows: ‘Mussolini was undoubtedly sent by God for the salvation of Italy.’”25 This letter is not included in Adami’s well-known collection. But Adami does print letters from 30 October 1922: “What do you think of Mussolini? I hope he will prove to be the man we need. Good luck to him if he will cleanse and give a little peace to our country!”; and from 1 November: “I wonder if Mussolini will introduce a little order into our national economy! I hope so.”26 Even more telling is a further passage, otherwise apparently unknown, but cited by Claudio Sartori, from a letter of 21 June 1924: “Mussolini? I trust that he will reassert himself. If not, better to go abroad.” Written at the height of the Matteotti crisis (to be explained below), this certainly undermines Pinzauti’s account.27

Julian Budden seizes on the letter to Adami of 30 October. “This tells us all,” he declares. “Fascist ideology meant nothing to Puccini.” He continues with a version of Pinzauti’s story about the PNF card, though this time Puccini is held to have accepted it for fear of prejudicing “his chances of being nominated Senator of the Realm.”28 No source is given. Nor does Budden explain what he means by “fascist ideology.” That is no straightforward matter, of course. Italian fascism was “a developing, pluralistic, decentralized, even disorderly movement,” as the historical sociologist Michael Mann puts it. Yet Mann’s own definition is useful, particularly since it focuses on “the rise of fascist movements rather than on established fascist regimes.” It is primarily this rise to which Puccini responded. Fascism, writes Mann, is “the pursuit of a transcendent and cleansing nation-statism through paramilitarism.”29 The “bottom-up” movement of armed fascist gangs sought violently—and paradoxically—to institute a “top-down” strong state shorn of elements judged inimical to the national cause (in the Italian case mainly socialism and communism) and capable of uniting all social classes in a single national project.

Much of Mann’s definition may seem alien to Puccini. The cosmopolitan outlook evinced by the composer’s interests, not least in his choice of subjects for libretti, rarely set in Italy, would suggest distaste for fascism’s “organic” nationalism. But there are further clues in the literature. Sartori draws attention to an anecdote told by the priest Dante Del Fiorentino:

Once when Giacomo was crossing the lake [Lago di Massaciuccoli] in his motorboat, a fisherman shook a fist at him, shouting, “It’s yours now, soon it will be our turn!” I was with him at the time. At first he did not seem unduly perturbed by the communist threat. “Let us go home,” he said quietly. But the lines on his face had suddenly deepened, and that sadness which showed when he was in repose was more intense than I had ever seen before.

“There’s a new spirit strangling Italy,” he complained. “There is a mortal sickness spreading through the world, and it has even come to our peaceful Tuscany. I have never intentionally done anyone any harm. I’ve tried to make people happy. Then why should that man hate me? There was hatred in his voice and in his face.”30

Puccini’s “mentality” was that of a bourgeois conservative, Sartori explains. Just as the composer could not understand the socialism of 1900, so now, in the aftermath of the First World War, he could not understand communism.31

We can go further. Del Fiorentino places the motorboat episode after 1922, yet it resonates more obviously with the period 1919–20, the so-called biennio rosso, marked by widespread union activism in the north of Italy, including strikes and factory occupations; in the cities there were also food riots. In rural areas there were similar upheavals.32 From 7 July 1919 we find the following in a letter from Puccini to Sybil Seligman: “I’m just off to Viareggio in the car; I hope they won’t take it away from me, because there are riots there owing to the high cost of living, and it appears that it’s half Boshevik.” On 3 September 1920, he explains to Seligman that he would not be going to see Il trittico at Cento (near Bologna) “because that district is known for the violence of its [leftist] demonstrations—and I’ve no desire to be made a target.”33 Even more strikingly than in the case of the confrontation on Lake Massaciuccoli (since the standoffs in Viareggio and Cento were imaginary), Puccini recognized himself as a class enemy of the protestors. He evidently feared not just the loss of property but physical injury.

Anyone looking for the explicit “pursuit of a transcendent and cleansing nation-statism” in Puccini’s letters will indeed be disappointed. Yet the basis for his support of fascism, as the antidote to class conflict in which he felt personally threatened, is nevertheless clear. The crucial term is “order.” As Mann explains, “The triad of property, order, and security, divinely ordained, was the ideological soul of the old regime.” In a situation where “order”—inseparably associated with property—is threatened, a bourgeois conservative like Puccini might start to find positive values in “nationalism, statism and class transcendence.”34 Certainly Puccini came to value a strong state. As he wrote to Seligman on 1 July 1920, “Italy is really in a bad way […] it’s going to be difficult for me, who am already an old man, to see good order restored in my country.” Four days later, he complained to the soprano Gilda Dalla Rizza: “How I miss the days in London! Here everything is rotten, one lives badly, without order, without any state protection, they say Giolitti will get round to it [Giolitti farà farà], but for now there’s trouble. How I long to live abroad!” And four days later still, to his friend Riccardo Schnabl: “The world is disgusting—you’re quite right to stay away. But I still believe in Giolitti and it seems that the revolts were repressed with an iron hand.”35 The interest in seeing leftist protests put down with violence is notable. Puccini made no secret of his distaste for socialism. As he put it to Renato Simoni, Adami’s co-librettist on Turandot, on 21 June 1921, “I very much liked Albertini’s speech in the Senate. He really put the socialists straight!” On 22 January 1922, he complained to Schnabl, with irony: “The socialist council [in Milan] is really keeping the city clean! Streets everywhere filthy with snow! Appalling.”36

These are not the words of a “resolutely apolitical” man, as Phillips-Matz describes him. The notion of apoliticism is in any case misleading. “As with all of those who profess indifference to politics,” Budden notes, Puccini “invariably gravitated towards the right.”37 But was he “indifferent” to Italian democracy or in fact opposed to it? Marotti cites a letter from 1898: “I don’t want to hear about election demonstrations et similia. […] I would abolish Chamber and deputies—that’s how much these eternal manufacturers of chatter annoy me. […] Let them elect Mundo or Felice the lifeguard at Viareggio, it’s all the same to me.”38 Contempt for parliament, fear and loathing of the revolutionary working class, distaste for socialism, desire for “order” and for decisive state intervention: it all adds up. We should not be surprised to find so much evidence of Puccini’s fascism.

Interpretation

A standard critical response, faced with material of the kind collected above, is to insist on the distinction between art and life. Yet musicologists no longer think along such lines, or at least not Anglophone musicologists who write on Puccini. Since the mid-1990s a consensus has developed that Turandot, in particular, “is thoroughly embedded in the emerging tropes of fascist discourse.”39 At the most general level, Alexandra Wilson suggests that Puccini’s last opera, “a work that looks simultaneously forwards and backwards, was […] a fitting emblem for Fascist Italy, caught between presenting itself to the world as modern and keeping faith with tradition.”40 Fascists could indeed express themselves in such broad terms. Thus Mussolini, in a speech given in Perugia on 5 October 1926, proclaimed:

Today Italy is a people with great possibilities, and that condition which all the greats longed for, from Machiavelli to Mazzini, has been realized. Today there is more: we are on the point of being unified morally.

Now, on a terrain that has been so well prepared, a great art can be reborn, which can be traditionalist and at the same time modern. We need to create, otherwise we will be exploiters of an old patrimony; we need to create the new art of our times, fascist art.41

There are few examples of art from any historical period that could not be described as containing both new and traditional elements. But the generality of Mussolini’s remarks was their pragmatic point. The Duce wanted to bind as many artists as possible to the fascist regime. He had no interest in laying down potentially exclusionary stylistic principles.

Commentators keen to view Turandot in a fascist light tend to look at the characters and plot. As Arman Schwartz writes, “It is […] surprisingly easy to read Turandot as a political allegory, one consistent with fascism’s own narrative of the degradation of post–World War I Italy and of Mussolini’s heroic rise.”42 Richard M. Berrong takes the line previously suggested by John Louis DeGaetani, according to which the opera’s chorus stands for “the desperate, angry Italian crowds that wandered through the street of Milan and other Italian cities during the inflation and unemployment after World War I.” Berrong further suggests that the “ice princess” Turandot, in her refusal to submit to a husband, herself allegorizes “the violence of a revolutionary populace.” Calaf, the “strongman,” wins Turandot over by force. Yet Puccini’s final opera is not “an opéra à clef.” Calaf is not Mussolini, since the message conveyed by the final scene is that “this strongman would need to rule the people, once he had subdued them, not by continued force, but by love.”43

Michael P. Steinberg and Suzanne Stewart-Steinberg remain unimpressed. The lack of “emotional or ethical conflict” experienced by Calaf at Liù’s death (in Act 3) marks him as the typically fanatical subject of fascism. Puccini delivers opera to spectacle, which is also opera’s “delivery to fascism, to its aesthetic of power through spectacle.”44 The confrontation of ice princess and phallic strongman in Turandot is startlingly misogynistic. As Schwartz points out, studies of fascist culture have suggested that “the opposition of virile hero and demonized woman […] is the central node of fascist and protofascist rhetoric.”45 Jeremy Tambling suggests that the “sexist” ascription of “hysterical femininity” to the figure of Scarpia in Puccini’s Tosca may be recuperated in terms of the undoing of bourgeois patriarchy. But Turandot is different: Calaf is non-hysterical. The “fantasy” in this opera “involves the complete victory of the male.” “Phallicism” is “central” to an operatic plot that features “Calaf as a fantasy where Mussolini was the reality.”46

Tambling’s musings on “the culture of fascism” were not well received. One of the most disparaging reviews, by H. Marshall Leicester Jr., is also the most thorough: it offers us a way forward. Tambling, we learn, is guilty of “retrospective determinism.” Since he knows that fascism was the historical “outcome of the cultural processes he examines,” he “reads as if […] fascism is the meaning […] of these processes.”47 Instead of throwing current theories of fascism at Turandot in an attempt to find a match, and having found one, assuming that the opera was fascist all along, we should investigate the opera’s “specifically fascist reception.”48 Leicester urges the employment of a Nietzschean “genealogy,” famously celebrated by Michel Foucault as a disruptive method of historical inquiry: “It shows the heterogeneity of what was imagined consistent with itself.”49 We see Turandot today and cry “Fascism!”—yet knowledge of the way Italian critics of the 1920s and ’30s assessed Puccini’s work may make us think twice.

To put it another way: we have seen what fascism meant to Puccini, but what did Puccini mean for fascism? For Mussolini, it was evidently worthwhile to keep the world’s most successful opera composer on his side. The Duce might not have been able to offer Puccini a national theater, but he doubtless had a hand in the composer’s nomination as “Senator of the Realm,” giving him a seat in the upper house of the Italian parliament.50 As we have already seen, Mussolini did not shy away from exploiting the propaganda value of the composer’s name on the very day of his death. The latter half of 1924 had been especially difficult for the Italian government. On 10 June, the socialist deputy Giacomo Matteotti was kidnapped and murdered by a gang of fascist thugs. Matteotti had not only been an outspoken critic of fascism; it seems that he was on the point of disclosing large-scale corruption at the highest level. Though Matteotti’s shallow grave was not discovered until 16 August, the authorities arrested the ringleader of the gang, Amerigo Dumini, as soon as 12 June. The following day, one hundred leftist deputies walked out of the parliament to form an “Aventine Secession.” Mussolini himself denied responsibility for the murder, instead blaming dissident fascists. But even if he was not directly involved, other high-ranking figures were implicated.51

It is in the context of this constitutional turmoil that, on 24 June, Puccini saw fit to reaffirm his support for Mussolini. The Matteotti crisis was still ongoing five months later, when the composer died. The Duce’s position had become, if anything, even more difficult after the tit-for-tat assassination by a rogue communist of a fascist deputy, Armando Casalini, on 12 September. For now elements within the Fascist Party demanded a violent response, which Mussolini refused to sanction. The situation was only resolved on 3 January 1925, when the Duce declared himself dictator, putting an end to parliamentary democracy in Italy for twenty years.52 At the end of November 1924, however, Italian parliamentary democracy was—just about—still in place. The fascists had won a large majority in elections held the previous April. Thus in his speech on Puccini’s death (see Appendix), Mussolini could refer to fascism as “controversial,” as if the PNF were a matter for free debate. The general atmosphere of political crisis explains the emphasis he placed on Puccini’s party membership. The support given to fascism by the composer of Madama Butterfly and La bohème offered a much needed legitimacy.

So much for Puccini’s name. Wilson tells us that “the Fascist regime” sought also “to appropriate his music for its own political ends.”53 This is most obviously true in the case of a rather minor effort, the Inno a Roma, composed in 1919 at the request of Puccini’s friend Prospero Colonna, then mayor of the Italian capital. The text, by Fausto Salvatori, is a version of Horace’s Carmen saeculare, a propagandistic work commissioned by the Emperor Augustus that was a great favorite of fascism, set at least three times in 1935 alone (the 2,000th anniversary of Horace’s birth).54 The following year, which saw Mussolini’s triumphant announcement of the foundation of the Italian Empire (that is, the conquest of Ethiopia), Puccini’s Inno was raised, so Jürg Stenzl tells us, to the status of “a kind of National Hymn.”55 As the youthful critic Renato Mariani put it:

This long-breathed page of melody is loudly sung today by the people, together with the other national hymns, when there are rallies, rites, ceremonies and anniversaries of victories. And it is particularly beautiful and significant that, in this way, the figure of Giacomo Puccini should always be present in the spirit of us Italians, who, celebrating and hymning the great events of fascist Italy, thus implicitly celebrate the glory of our unforgettable artist.56

In August 1937, the Inno a Roma was used to preface open-air performances of opera to mass audiences at the grandiose Roman Baths of Caracalla, a scheme introduced that year by Prospero Colonna’s son Piero, who became “governor,” the fascist replacement for mayor, of the city in 1936.57 The first season at the Baths of Caracalla featured a production of Tosca; the following year there was Turandot, reprised in 1939. The novelist Gore Vidal, present at Turandot that summer, left the following account:

We sit outside in a railed-off box, under the hot dark sky. In the next box, Mussolini, wearing a white uniform. At the first interval, he rose and saluted the soprano. Audience cheered. Then he left the box. As he passed me, I smelled heavy cologne. Onstage, he saluted the audience—Fascist arm outstretched. Vanished.58

Puccini’s operas remained popular with Italian audiences throughout the fascist period. Between 1935 and 1943 there were eighty-seven productions in the state-subsidized opera houses and major festivals alone.59 Puccini’s operas also featured heavily in the mass theatrical events, such as those held at the Baths of Caracalla, that were such a distinctive feature of the 1930s, the outcome of Mussolini’s declaration that fascist culture should “go towards the people.” Here is Vincent Seligman in the full flush of his fascist enthusiasm:

It is scarcely to be wondered at that the Duce should have had other and more pressing problems to attend to at that time [the reference is to his meeting with Puccini]. But no aspect of Italian life, however insignificant, escapes his all-seeing eye for long, and the time was to come, long after Puccini’s death, when the operatic stage of Italy received a tremendous new stimulus, not indeed through the financing of costly seasons abroad, but by bringing opera at home within the reach of the slenderest purse at those open-air summer performances where, for a few lire, the people can enjoy first-rate opera to their hearts’ content. Only the other day I chanced in Italy on a number of the Corriere Della Sera (August 8th, 1937) which contained three long notices of outdoor performances given on the previous night; in the Castello at Milan Butterfly before an audience of 20,000; at Verona Turandot before a huge public of 25,000 which included Gabriele D’Annunzio; in Rome an “extraordinary” performance of Bohème with Gigli as Rodolfo.60

Puccini’s operas were also a mainstay of the celebrated carri lirici, mobile theaters that took opera on tour to provincial centers from 1930 onward.61

At the time of Puccini’s death, Wilson writes, Italian critics, “card-carrying Fascists” among them, praised the composer in “extravagantly imperialist terms.” The “greatness” of Puccini’s music, as Adami unblushingly records, was viewed not just as “artistic” but also as “propagandistic”: an advertisement for Italian cultural achievement with a global reach.62 Wilson points out how Il popolo d’Italia, Mussolini’s own newspaper, proclaimed that “whenever a Puccini opera was advertised on a theater bill, a ‘miracle’ of unity occurred, and ‘all class divisions ceased.’”63 This is fascist “class transcendence” in action. Open-air performances in Milan, Verona, or Rome were presumably intended to have this same socially harmonizing role.

Such instrumentalization of Puccini’s work says little about its content. In these open-air performances, the Steinbergs suggest, following Jeffrey Schnapp on the carri lirici, the medium was the message.64 Class transcendence was apparently not the message of Turandot itself. Both Schwartz and Wilson survey the opera’s initial reception. And from a political perspective, there is little to report.65 Consider, for instance, the lengthy review by Adriano Lualdi, a composer, conductor, and critic who was also a top-level musical bureaucrat under the regime, an ardent fascist with “a great deal of clout,” as Harvey Sachs puts it.66 Lualdi’s review is certainly marked by gross sexism, but of the critic’s political views there are no more than hints, as when he remarks that the “proof” of Puccini’s “qualities as an artist […] of good Italian stock” lies in the manner in which, for the composer, the concept of “life” is indissolubly linked with that of “movement.” The reader is presumably to understand a reference to fascism’s self-image as unrestingly dynamic.67 For the most part, Lualdi sticks to matters of primarily aesthetic interest. He compares the libretto to it sources (Gozzi, Schiller, Andrea Maffei), gives a blow-by-blow account of the score, and offers his judgments with respect to the relative success of the opera’s various sections.68

It seems clear, especially from Wilson’s account, that Mussolini’s accession to power made little impact on the way critics responded to Puccini’s music. Writing about Turandot, they worried about the “honesty and homogeneity” of the composer’s work, just as they had been doing ever since the premiere of La bohème.69 Wilson in fact expresses some perplexity:

One might have expected a continuation of the anti-Puccini rhetoric of Torrefranca and the Voce circle in the Fascist era, given their use of a proto-Fascist language of virility, misogyny, imperialism and opposition to the bourgeoisie. Rather than emulating such thinkers, however, the most prominent Fascist critics drew instead upon the nationalist hagiography favoured by Puccini’s patrons and magnified it.70

Wilson attempts to solve this apparent contradiction by noting that while Torrefranca was an intellectual and a progressive, Lualdi was a conservative pragmatist.71 But Lualdi’s review of Turandot, though certainly nationalistic in feeling, is far from overblown in this respect. Nor is it hagiographical: the critic maintains his autonomy.

Claudio Casini views the situation differently:

Fascist musical politics were in the hands of the avant-gardes, who wanted to break precisely with opera and with Puccini. Reserved for opera, and incontestably popular, were the carri di tespi [lirici], the open-air spectacles at the Baths of Caracalla and the Verona Arena, the prestigious seasons at La Scala, which could not be prised away from the rich Milanese bourgeoisie, and at the Teatro dell’Opera, which would be used for state ceremonies, and the future receptions for Chamberlain and Hitler. But the favourite institutions of the regime would be the Festival of Contemporary Music in Venice, the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, the season at the Augusteo [the principal concert hall in Rome], where there was no place for Puccini, and where, in various ways, Casella, Pizzetti, Malipiero, Respighi made their names, and the whole constellation that surrounded these four signal musicians of twentieth-century Italy.72

Puccini’s operas may have retained their popularity, but for many in the Italian musical elite of the 1920s and ’30s, his work was passé, at best. In a widely read study of the younger generation of composers, the critic and musicologist Domenico de’ Paoli described Puccini as the preeminent musician of the “Umbertine” petty bourgeoisie of the late nineteenth century, the representative of “the sensibility and mentality of this class.” With each opera, Puccini’s musical language became “ever more refined, rich and varied.” But this stylistic development stood in ever greater tension with the composer’s sensibility, which did not evolve in a parallel manner, and which, de’ Paoli declared, “is no longer ours.”73

An illustration of how old-fashioned Puccini had come to sound is provided by the critical reception of the only opera premiered under fascism beside Turandot that achieved anything like a popular success, though it has now long been forgotten: Il dibuk (Milan, 1934) by Lodovico Rocca. This tale of metaphysical goings-on in the Pale of Settlement, based on the celebrated play by the ethnographer, activist, and writer An-Sky, is set by Rocca for the most part in the Mussorgsky/Debussy recitative style that found its leading Italian exponent in Ildebrando Pizzetti. But in the opera’s final section, where the young lovers are joined, Tristan und Isolde–like, in an otherworldly realm, Rocca responds to the verse of his librettist Renato Simoni (he of Turandot) in a manner that clearly harks back to the more lyrical vocal idiom associated with Puccini. Opinion was mixed. As Gian Francesco Malipiero commented, in ironic vein, “There was a little of that divine melody that I consider somewhat too conventional.”74

Rocca was not given to aesthetico-political pronouncements. It would be inappropriate to read too much into this turn to verismo style at the end of his most successful work. The same cannot be said of the music shown in Example 1, from the tenor aria at the start of Act 2 of I Shardana (Naples, 1959) by Ennio Porrino. Porrino’s previous opera, the one-act Gli Orazi (Milan, 1941), was a display of heroic romanità in the form of “teatro mussoliniano,” originally intended for production at the Baths of Caracalla. The composition of his second opera, set in the prehistoric culture of Sardinia, was financed in part by a onetime payment from the Ministry of Popular Culture, and completed, barring revisions, in 1944 under the Republic of Salò, the Nazi puppet state of 1943–45, to which—in contrast to Rocca in Turin, who refused to sign allegiance—Porrino had moved north from Rome to join.75 I Shardana was doubtless meant to receive the same mass-theatrical treatment intended for Gli Orazi. Porrino’s shameless cribbing of the distinctive opening harmonic progression of Puccini’s “Nessun dorma” at the beginning of Torbeno’s aria seems fully in line with an attempt to “go towards the people.”

Example 1. Ennio Porrino, “Aria di Torbeno,” I Shardana (Gli uomini dei nuraghi), Act 2, mm. 171–76.

Porrino was also active in the late fascist period as a polemical journalist: his target was the neoclassicism of Alfredo Casella, which he denounced as “anti-expressive, internationalized” and productive of “ugliness.”76 In a letter of August 1941, he raved that the “clique” around Casella were “all authentic antifascists […] internationalizing and defeatist.”77 Casella saw things very differently. His writings, in fact, complicate the idea that the Torrefranca line of criticism disappeared under the regime. The history of the last fifty years of Italian music, so Casella declares in a characteristically brazen 1935 piece, is that of the rise of instrumental composition and the concomitant decline of opera.78 Casella has nothing against Romanticism per se. But verismo was decadent with respect to Romanticism, a “false tradition” that expressed “the rhetoric and the academicism of the petty bourgeois and liberal-democratic prewar era.”79 Contemporary Italian composers, Casella declares, have chosen to abandon “romantic positions” in favor of an art that is “constructive and linear.”80 Unlike the veristi, who imported a foreign (that is, French) idiom and attempted to Italianize it, they choose purely Italian sources as models, the pre-Beethovenian symphonic and chamber forms of the eighteenth century. This is precisely what Torrefranca was hoping for, it should be added.81 But there is more. In their gradual throwing off of foreign influences over the course of the twentieth century, Italian composers have followed a path comparable to that of the “national consciousness” generally.82 “In its sobriety, in its dynamism, in its audacity, in its architectonic sense, in its absence of any rhetoric,” Italy’s new music exemplifies a truly fascist art.83

Casella and Porrino represent extreme positions. And their writings are rather untypical of critical discourse from the fascist period in their explicitly political character. Much more characteristic is the article by Lualdi, cited above, in which the author’s politics are soft-pedalled. Marotti presents a similar case. As we saw earlier, he portrays Puccini’s political opinions as thoroughly fascistic. But in a “Preludio ad una critica” from 1936, an assessment of Puccini’s compositional career as a whole, political concerns are almost entirely absent. Marotti regards the decidedly political pre–First World War critiques by the likes of Torrefranca as laughable. Vociferous condemnation of Puccini’s work as either “bourgeois” or “international” simply misses its target. Objectively, Puccini’s music is Italian; subjectively it is cosmopolitan. As for his music’s “bourgeois” character, this is a mark of its Italianness. Puccini’s work is stylistically progressive, but finds no place for arbitrary revolution.84

Political reticence in discussing works of art was not confined to musicians. As the cultural historian Ruth Ben-Ghiat explains, “Many literary figures, even those of convinced fascist faith, considered it bad form to write overtly political works.” Nor would they “mandate the style or content of the new national culture.”85 Crucial here was the influence of the philosopher, historian, and literary critic Benedetto Croce. He may have been the most prominent public opponent of fascism resident in Italy, but this fact did not persuade fascist critics to abandon their commitment to the autonomy of the aesthetic, which frequently took its cue from Croce’s argument that artworks were essentially lyric intuition and thus unconnected, qua art, to the sphere of the practical (where politics resided).86 Even the notorious 1932 “Manifesto di musicisti italiani per la tradizione dell’arte romantica dell’ottocento,” a thinly veiled attack on Malipiero and Casella, which was signed by Lualdi, Pizzetti, Respighi, and others, and which demanded a return to the tradition of Verdi and Puccini, makes no explicit mention of fascism at any point. Instead the document refers somewhat decorously to an “ongoing revolution that is revealing once again the immortality of the Italian genius.”87

There seems no evidence to suggest that Puccini himself thought of Turandot in political terms. To most educated Italians of the 1920s and ’30s the idea would have appeared vulgar, if not simply a philosophical error. Even the crudely politicizing Casella would have found the notion absurd. Turandot he regarded as only partially successful. Though Puccini’s work “certainly testifies […] to a clear desire to break new ground,” this only goes to prove that “the romantic and realist theatrical forms are past and gone.”88 The best music in Turandot belongs to Liù, Casella felt, but might just as well have belonged to Mimì. And how, he asked in 1935, could a genuinely fascist art be fashioned from the expressive forms of yesterday’s bourgeoisie?89

Remove the explicitly political angle, and Casella gives us the standard line on Puccini held by Italy’s “progressive” musical elite of the fascist period. We have seen this already in de’ Paoli; it was given authoritative expression by the leading critic, editor, and arts administrator Guido M. Gatti in a lengthy article from 1927. Returning to the topic for the tenth anniversary of Puccini’s death, Gatti saw no reason to alter his views. The composer’s work was “feminine,” inasmuch as it “did not set its mark on its times, but was fertilized and marked by them.” Puccini’s bourgeois Romanticism catered perfectly to the Milanese operatic public of the last quarter of the nineteenth century. To be sure, Turandot bears witness to a desire “to get out of the dead-end of early twentieth-century opera.” But Puccini’s powers “failed him when he most needed them.”90

As Cesare Orselli points out, for a “serious critic” of the 1930s to mount a defense of Puccini was almost unheard of.91 Yet there were exceptions. An article by Renato Mariani, whose thoughts on the Inno a Roma are cited above, gives us what we have been looking for: an assessment of Turandot in fascist terms by a fascist critic. Turning on its head the opinion of Gatti, who had argued that over the course of his career Puccini’s musical language had become increasingly impoverished, Mariani assaults the “mean and limited passion of those many persons who, if they can love and understand the little episode of Bohème, are spiritually unable to grasp the elevated, human, collective, choral meaning that is fixed in Turandot.”92 Mariani’s reading lacks explicit politicization, as is to be expected. Yet it is not hard to catch the political intent of a declaration, in 1936, that Turandot expresses “the positive values of healthy, living modernity, of absolute, indisputable contemporaneity.”93 The key here is an interpretation of La fanciulla del West as marking a break with the “intimate and restricted drama” of the composer’s previous operas.94 From Fanciulla onward, Puccini’s work begins to resonate with the “external world” that surrounds it, with “passions of a collectively human and emotional character.”95 Evidently we are meant to understand a parallel to the transition from the atomized individuality of bourgeois liberalism to the organic collectivity of fascism. Turandot, in its “great, unitary and choral conception,” marks the “victorious” fulfillment of this process.96 In such terms, we might say, Puccini’s final opera stands as a fulfillment of Mussolini’s exhortation: “Find a dramatic expression for the collective’s passions and you will see the theaters packed.”97 Class transcendence turns out to be the message of Turandot, after all.

In Foucault’s “genealogical” terms, the investigation has paid off. Mariani’s is a “fascist” reading quite unlike those proposed more recently, in which, as we saw, Calaf is dressed (metaphorically) in a black shirt as he takes possession of his princess. For Mariani, the somewhat backward-looking vocal styles given to Calaf and Liù make these characters “less choral” than Turandot herself, whose “new vocality” makes her the “absolute protagonist of the intimate drama and the choral drama.”98 To dress Calaf—this “passionate lover typical of Puccini’s theater,” as Mariani put it elsewhere99—in a real black shirt (as one can hardly believe that no recent director has been tempted to do), is doubtless to produce a political frisson among today’s operatic audiences. But it is not, of course, to produce a “fascist” reading of the opera, rather the opposite. And to an Italian audience of the 1930s, one imagines, such a gesture would simply have made no sense.

Appendix: Mussolini’s Speech to the Chamber of Deputies, 29 November 1924

Honorable colleagues!

I have the deep sadness of communicating distressing news to the Chamber.

In a clinic in Brussels, where he had gone once the illness that was afflicting him had assumed an inexorable course, Giacomo Puccini died today. (The Chamber rises to its feet.)

I am sure that the sadness that overwhelms us in this moment is profoundly shared by the entire Italian people and, one can say, by the entire civilized world. Each one of us has experienced moments of Puccini’s music, each of us has been moved before the unforgettable protagonists whom Puccini brought to the stage, whom he brought to life with the force of his music.

This is not the time to discuss the qualities and the nobility of his creations. It is certain that, in the history of Italian music and in the history of the Italian spirit, Giacomo Puccini occupies the most eminent of positions. Nor do I want at this time to dwell on the fact that some months back this illustrious musician asked for the card of the National Fascist Party. He wanted to make this gesture of adherence to a movement which is controversial, the object of controversy, but which is also the only living thing there is today in Italy.

Having recalled that, we want, affiliations aside, to honor in Giacomo Puccini the musician, the maestro, the creator. His music has moved many generations, including ours; it cannot die, for it represents a moment of the Italian spirit.

Let all the people come together at this time. I believe that the Chamber should make itself the interpreter of all the Italian people, raising a tribute of admiration, of devotion, and of sorrow to the memory of this noblest of spirits. (Lively approbation.)

1. Mary Jane Phillips-Matz, Puccini: A Biography (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2002), 282–83.

2. See Richard Specht, Giacomo Puccini: The Man, His Life, His Work, trans. Catherine Alison Phillips (London: Dent, 1933), 21; Vincent Seligman, Puccini Among Friends (London: Macmillan, 1938), 351; Guido Marotti, Giacomo Puccini intimo, 2nd ed. (Florence: Vallecchi, 1943), 169.

3. Phillips-Matz cites Michele Girardi, who relies on Leonardo Pinzauti. Pinzauti himself gives no source for the November date, but presumably follows the account of Guido Marotti. See Michele Girardi, Puccini: His International Art, trans. Laura Basini (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2000), 436; Leonardo Pinzauti, Puccini: Una vita (Florence: Vallecchi, 1974), 171; Marotti, Giacomo Puccini intimo, 169.

4. See Phillips-Matz, Puccini, 283; Girardi, Puccini, 436.

5. “Presidente del Consiglio dei ministri” was and remains the official title of Italian prime ministers.

6. Seligman, Puccini Among Friends, 351.

7. Pinzauti, Puccini: Una vita, 171.

8. See Fiamma Nicolodi, Musica e musicisti nel ventennio fascista (Fiesole: Discanto, 1984), 37–38; and for Puccini’s membership of the Permanent Commission, see Eugenio Gara, ed., Carteggi pucciniani (San Giuliano Milanese: Ricordi, 1986), 533.

9. Raffaello de Rensis, Mussolini musicista (Mantua: Edizioni Paladino, 1927), 27–28.

10. In Palazzo Chigi in Rome.

11. Marcello Piacentini was the leading architect of fascist Italy. The Teatro Costanzi in Rome was remodeled to his design in 1926–27, reopening in 1928 as the Teatro Reale dell’Opera. Presumably Mussolini had the expenditure for this project in mind.

12. Marotti, Giacomo Puccini intimo, 169.

13. Phillips-Matz, Puccini, 282.

14. Edmondo and Duilio Susmel, eds., Opera omnia di Benito Mussolini, 35 vols. (Florence: La Fenice, 1951–63), 21:188–89. A translation of Mussolini’s speech is given in the appendix to this essay.

15. Marotti, Giacomo Puccini intimo, 168.

16. Girardi, Puccini, 436.

17. Pinzauti, Puccini: Una vita, 169.

18. Seligman, Puccini Among Friends, 290–91.

19. See Nicolodi, Musica e musicisti, passim, but see esp. the documentary section, 306–472.

20. Giuseppe Adami, Puccini (Milan: Treves, 1935), 183.

21. Agostino Depretis, Francesco Crispi, and Giovanni Giolitti were all prime ministers of Italy at various times during the “liberal” period, 1871–1922.

22. Marotti, Giacomo Puccini intimo, 168–69, 170; translation based on Harvey Sachs, Music in Fascist Italy (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1987), 104.

23. The “March on Rome” was a display of paramilitary strength that accompanied Mussolini’s appointment as prime minister. For more details, see R. J. B. Bosworth, Mussolini (London: Arnold, 2002), 167–69.

24. See Nicolodi, Musica e musicisti, 36. Her source is G. A. Chiurco, Storia della rivoluzione fascista, 5 vols. (Florence: Vallecchi, 1929), 5:273.

25. Adami, Puccini, 183.

26. Giuseppe Adami, ed., Letters of Giacomo Puccini, Mainly Connected with the Composition and Production of His Operas, trans. Ena Makin, rev. ed. (London: Harrap, 1974), 297, 89.

27. See Claudio Sartori, Puccini (Milan: Nuova Accademia Editrice, 1958), 334. Sartori does not give the name of the recipient of this letter, but it is clearly Riccardo Schnabl. In the index to Puccini’s published correspondence with Schnabl, there is a reference to Mussolini listed for letter 133. But turning to this letter, dated 21 June 1924, one finds not just a lack of reference to the Duce, but also a curious four-line gap in the middle of the page. See Giacomo Puccini, Lettere a Riccardo Schnabl, ed. Simonetta Puccini (Milan: Emme Edizioni, 1981), 239. Evidently the text had been cut at proof stage: “Mussolini? Io ho fiducia che si riaffermerà, se fosse il contrario meglio prendere la via dell’estero.”

28. Julian Budden, Puccini: His Life and Works (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 436.

29. Michael Mann, Fascists (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 100, 1, 13.

30. Dante Del Fiorentino, Immortal Bohemian: An Intimate Memoir of Giacomo Puccini (New York: Prentice-Hall, 1952), 194–95.

31. Sartori, Puccini, 332.

32. For a succinct account, see Martin Clark, Modern Italy: 1871 to the Present, 3rd ed. (Harlow, UK: Pearson Education, 2008), 247–53.

33. Seligman, Puccini Among Friends, 303, 315.

34. Mann, Fascists, 63–64.

35. Seligman, Puccini Among Friends, 308; Gara, Carteggi pucciniani, 491–92; Puccini, Lettere a Riccardo Schnabl, 84.

36. Gara, Carteggi pucciniani, 509; Puccini, Lettere a Riccardo Schnabl, 160. Luigi Albertini was the long-standing editor of the liberal daily Corriere della sera.

37. Phillips-Matz, Puccini, 284; Budden, Puccini, 436.

38. Marotti, Giacomo Puccini intimo, 171; the translation is from Sachs, Music in Fascist Italy, 102.

39. Arman Schwartz, “Mechanism and Tradition in Puccini’s Turandot,” Opera Quarterly 25/1–2 (2009): 32.

40. Alexandra Wilson, The Puccini Problem: Opera, Nationalism, and Modernity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 193.

41. Susmel, Opera omnia di Benito Mussolini, 22:230.

42. Schwartz, “Mechanism and Tradition,” 32.

43. John Louis De Gaetani, Puccini the Thinker: The Composer’s Intellectual and Dramatic Development (New York: Peter Lang, 1987), 43; Richard M. Berrong, “Turandot as Political Fable,” Opera Quarterly 11/3 (1995): 70, 72, 74n30.

44. Michael P. Steinberg and Suzanne Stewart-Steinberg, “Fascism and the Operatic Unconscious,” in Opera and Society in Italy and France from Monteverdi to Bourdieu, ed. Victoria Johnson, Jane F. Fulcher, and Thomas Ertman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 275, 276.

45. Schwartz, “Mechanism and Tradition,” 32–33. See the discussion of the stage direction for the “kiss” in Act 3, in Roger Parker, Remaking the Song: Operatic Visions and Revisions from Handel to Berio (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2006), 96–98. For feminist readings of the opera, see Catherine Clément, Opera, or the Undoing of Women, trans. Betsy Wing (London: Virago, 1989), 96–102; Patricia Juliana Smith, “Gli enigmi sono tre: The Devolution of Turandot, Lesbian Monster,” in En Travesti: Women, Gender Subversion, Opera, ed. Corinne E. Blackmer and Patricia Juliana Smith (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995), 242–84.

46. Jeremy Tambling, Opera and the Culture of Fascism (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996), 126, 151, 149, 157.

47. H. Marshall Leicester Jr., Review of Tambling, Opera and the Culture of Fascism, Cambridge Opera Journal 10/1 (1998): 122.

48. Ibid.

49. Michel Foucault, “Nietzsche, Genealogy, History,” trans. Donald F. Bouchard and Sherry Simon, in The Foucault Reader: An Introduction to Foucault’s Thought, ed. Paul Rabinow (London: Penguin, 1991), 82.

50. Puccini had been angling for this appointment since 1919; his nomination was approved in the Senate on 23 November 1924. See Budden, Puccini, 423; “Le commemorazioni,” Musica d’oggi 7/3 (1925): Supplement, 50.

51. See Bosworth, Mussolini, 192–201.

52. Ibid., 201–3.

53. Wilson, The Puccini Problem, 221.

54. See Ben Earle, Luigi Dallapiccola and Musical Modernism in Fascist Italy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 194.

55. Jürg Stenzl, Von Giacomo Puccini zu Luigi Nono: Italienische Musik 1922–1952: Faschismus, Resistenza, Republik (Buren: Knuf, 1990), 64.

56. Renato Mariani, Giacomo Puccini (Turin: Arione, 1938), 28. The other “national hymns” were Giovinezza (the anthem of the Fascist Party) and the Marcia reale (the national anthem).

57. For more details on the Inno, see Arnaldo Marchetti, “Tutta la verità sull’ ‘Inno a Roma’ di Puccini,” Nuova rivista musicale italiana 9/3 (1975): 396–408; Michael Kaye, The Unknown Puccini (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987), 127–41, which includes the music. Both Marchetti and Kaye give the date of the Caracalla performance as 1935, but this is a mistake. See Sandro Carletti, “Istituzione e ripresa degli spettacoli alle Terme di Caracalla,” in Cinquant’anni del Teatro dell’Opera, ed. Jole Tognelli (Rome: Bestetti, 1979), 92.

58. Gore Vidal, Palimpsest: A Memoir (London: Deutsch, 1995), 86; see also Carlo Marinelli Roscioni, “Cronologia,” in Tognelli, Cinquant’anni del Teatro dell’Opera, 234–36.

59. See Nicolodi, Musica e musicisti, 25.

60. Seligman, Puccini Among Friends, 351–52n2.

61. See Emanuela Scarpellini, Organizzazione teatrale e politica del teatro nell’Italia fascista, 2nd ed. (Milan: LED, 2004), 360.

62. Wilson, The Puccini Problem, 190; Adami, Puccini, 184.

63. Wilson, The Puccini Problem, 186.

64. Steinberg and Stewart-Steinberg, “Fascism and the Operatic Unconscious,” 272; Jeffrey Schnapp, Staging Fascism: 18BL and the Theater of Masses for Masses (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1996), 21.

65. Schwartz finds a certain verbal and visual fascist rhetoric in the early reports, but nothing more substantial. See his “Mechanism and Tradition,” 33.

66. Sachs, Music in Fascist Italy, 21.

67. Adriano Lualdi, Serate musicali (Milan: Treves, 1928), 258. For Lualdi’s sexism, see p. 248, and the discussion in Parker, Remaking the Song, 98–99. On fascism’s “futural dynamic,” see Roger Griffin, Modernism and Fascism: The Sense of a Beginning Under Mussolini and Hitler (Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007).

68. Lualdi, Serate musicali, 243–49, 249–58, 258–61.

69. Wilson, The Puccini Problem, 218, passim.

70. Ibid., 191.

71. Ibid.

72. Claudio Casini, Giacomo Puccini (Turin: UTET, 1978), 449.

73. Domenico de’ Paoli, La crisi musicale italiana (1900–1930) (Milan: Hoepli, 1939), 33, 34–35.

74. See Luisa Passerini, Love and the Idea of Europe, trans. Juliet Haydock with Alan Cameron (New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2009), 258. That an opera with a libretto based on material drawn from Yiddish folklore could be successful in fascist Italy is evidence of the lack of official anti-Semitism before 1938. From 1939, however, the opera could no longer be performed, despite the protests of the composer (who was not Jewish), and after the war it never regained its initial popularity. See Passerini, Love and the Idea of Europe, 260–61. Further discussion of the opera and its sources may be found in Michal Grover-Friedlander, Operatic Afterlives (New York: Zone Books, 2011), 115–50.

75. For Gli Orazi and the circumstances of the composition of I Shardana, see Myriam Quaquero, Ennio Porrino (Sassari: Delfino, 2010), 157–79, 207–11, 226–28; Nicolodi, Musica e musicisti, 444–46; Giovanni Sedita, Gli intellettuali di Mussolini: La cultura finanziata dal fascismo (Florence: Le Lettere, 2010), 209. For Rocca’s resistance to Salò, see Passerini, Love and the Idea of Europe, 261.

76. Ennio Porrino, “Il problema della musica dotta e della musica popolare,” Il musicista 5/4–5 (1938): 61–66; repr. in Ennio Porrino, Questioni musicali 1932–1959, ed. Giuanne Masala (Stuttgart: Masala, 2010), 41–48, quote at 44–45.

77. Quaquero, Ennio Porrino, 182.

78. Alfredo Casella, “Problemi della musica contemporanea italiana,” La rassegna musicale 8/3 (1935): 161–73; repr. in La rassegna musicale, ed. Luigi Pestalozza (Milan: Feltrinelli, 1966), 258–68, quote at 259.

79. Casella, “Problemi,” 264.

80. Ibid., 262.

81. Ibid., 258, 262–63; and see, for example, Fausto Torrefranca, “‘Per una coscienza musicale italiana,” La voce 2/38 (1910): 385–86.

82. Casella, “Problemi,” 259.

83. Ibid., 264–66.

84. Marotti, Giacomo Puccini intimo, 210–11, 212–13.

85. Ruth Ben-Ghiat, Fascist Modernities: Italy, 1922–1945 (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2001), 47, 26.

86. For Croce’s aesthetics, and a sense of how they fit into his system as a whole, see his Breviary of Aesthetics: Four Lectures, trans. Hiroko Fudemoto (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2007).

87. The complete text of the “Manifesto of Italian Musicians on Behalf of the Tradition of Nineteenth-Century Romantic Art” can be read in Nicolodi, Musica e musicisti, 141–43; excerpts in English translation are available in Sachs, Music in Fascist Italy, 24–25.

88. Alfredo Casella, “Puccini’s Last Opera,” Christian Science Monitor, 29 May 1926.

89. Ibid.; Casella, “Problemi,” 265.

90. Guido M. Gatti, “Puccini dieci anni dopo la morte,” Pan 2/11 (1934): 412, 410, 412. The previous, longer article is Guido M. Gatti, “Rileggendo le opere di Puccini,” Il pianoforte 8/8 (1927): 257–71; repr. in Claudio Sartori, ed., Giacomo Puccini (Milan: Ricordi, 1959), 89–108. There is also a version in English, “The Works of Giacomo Puccini,” trans. Theodore Baker, The Musical Quarterly 14/1 (1928): 16–34.

91. Cesare Orselli, “Verismo e umanità negli scritti di Mariani,” in Renato Mariani, Verismo in musica e altri studi, ed. Cesare Orselli (Florence: Olschki, 1976), 12.

92. Renato Mariani, “L’ultimo Puccini,” La rassegna musicale 9/4 (1936): 133–40; repr. in Sartori, Giacomo Puccini, 113–21; also in Mariani, Verismo in musica, 64–70, quote at 65. For Gatti, see “The Works of Giacomo Puccini,” 30.

93. Mariani, “L’ultimo Puccini,” 70.

94. Ibid., 68.

95. Ibid., 65.

96. Ibid., 67, 69.

97. See Mussolini’s speech of 28 April 1933 to the Italian Society of Authors and Publishers, cited in Steinberg and Stewart-Steinberg, “Fascism and the Operatic Unconscious,” 270; the translation is from Schnapp, Staging Fascism, 33.

98. Mariani, “L’ultimo Puccini,” 69.

99. Mariani, Giacomo Puccini, 31.