CHAPTER 6

Harnessing Energy

A DEMONSTRABLY HIGH WORK ETHIC HAS BEEN THE FOUNDATION OF MANY successful leadership careers. As Vince Lombardi once stated, “The price of success is hard work, dedication to the job at hand, and the determination that whether win or lose, we have applied the best of ourselves to the task in hand.” It seems almost perverse to believe that hard work has little or low value because, throughout organizations, it is the primary means through which employee commitment and effectiveness is determined.

Contrasting a high work ethic with its counterpart—laziness—reveals its importance. We’ve never heard a compelling case for laziness in a work context, certainly not as a positive contributor to role effectiveness and career progression. We have yet to meet an effective leader who is fundamentally lazy, so hard work is definitely the desired contribution. However, a person who is seen as underreacting when situations arise isn’t necessarily lazy. Just because we don’t see or feel their determination to react quickly doesn’t mean they lack commitment or can’t make a contribution.

A lack of action or reaction may indicate a need for more analysis to understand what is required. A leader who disagrees with a proposed course of action may see that it is inadequate and poorly thought through and that accelerating toward implementation will have unintended consequences that will generate more problems in the future. If the urgency to act is partnered with a strong level of certainty and assertiveness from their colleagues, it’s often easier to disengage and say nothing. It is therefore important, as we progress with a description of the importance of personal drive to an individual’s success, that this drive be predicated on the effective thought and analysis that should precede it.

Every living thing, from prokaryotic cells (the simplest cells we have discovered) to the most complex creatures (such as mammals) requires a source of energy. Similarly, organizations and structures require a source of energy to build or maintain function. With respect to organizations, top-performing leaders know this all too well. They operate akin to the manager of a city’s power plant, carefully calculating and predicting supply and demand, diligently balancing different sources of supply, operating efficiently to manage costs and optimize profit, looking ahead to predict variable demand, and reacting to demands for “cleaner” energy. They are sensitive to the most effective and efficient energy source. They need enough energy to power themselves and even more to power others. Not everyone is driven by the same amount and type of energy. The best leaders we have studied think and act flexibly, fully aware of the energy others need and how much they need themselves. They scan the dials and gauges that measure energy source, flow, and consumption, ever mindful of the need to never go into the red zone, with everyone’s red zone set at slightly different levels.

As you consider this chapter, and the complex elements of top-performing leaders, keep the source-of-energy metaphor in mind. As a high-performing leader, you are really emulating the manager of a power plant.

COMPETITORS AND ACHIEVERS

Research Definition: A strong self-starting nature that pushes a leader to do more and achieve more may be the consequence of an internal drive to achieve or an external focus on winning.

Individual leaders are driven and motivated by different things. They need and consume different types of energy. Understanding these differences provides insight into how a leader might productively engage in work that drives value and ultimate benefit to society. One of the biggest sources of confusion that impairs our ability to understand a person’s drive is the assumption of competitiveness. Commitment not only is associated with determination, tenacity, and hard work but also is synonymous with a competitive instinct. This assumption is almost certainly wrong and can lead to mismanagement and disengagement.

To illustrate this more clearly, let’s consider Olympic athletes who compete at the highest levels of their sport. These phenomenal specimens spend their athletic lifetime training to carve out a “competitive edge” in hopes of winning a medal. And yet, in postevent interviews, it’s not uncommon for losing athletes to express a great deal of pride and satisfaction at having achieved a “personal best” in their performance. They reached a level not previously achieved in their own training and competitions and feel good about this despite having lost. A 1995 research paper explained the psychology of this phenomenon of some people being happier when they don’t win, even when they strive to. They termed it the “less is better” effect, and it perfectly describes the difference between a competitive drive and an achievement drive.1

To the true competitor, this represents a form of rationalization—a ready-made excuse for not winning. The defense in these situations is that the athlete never had a realistic prospect of winning—they are willing participants rather than competitors.

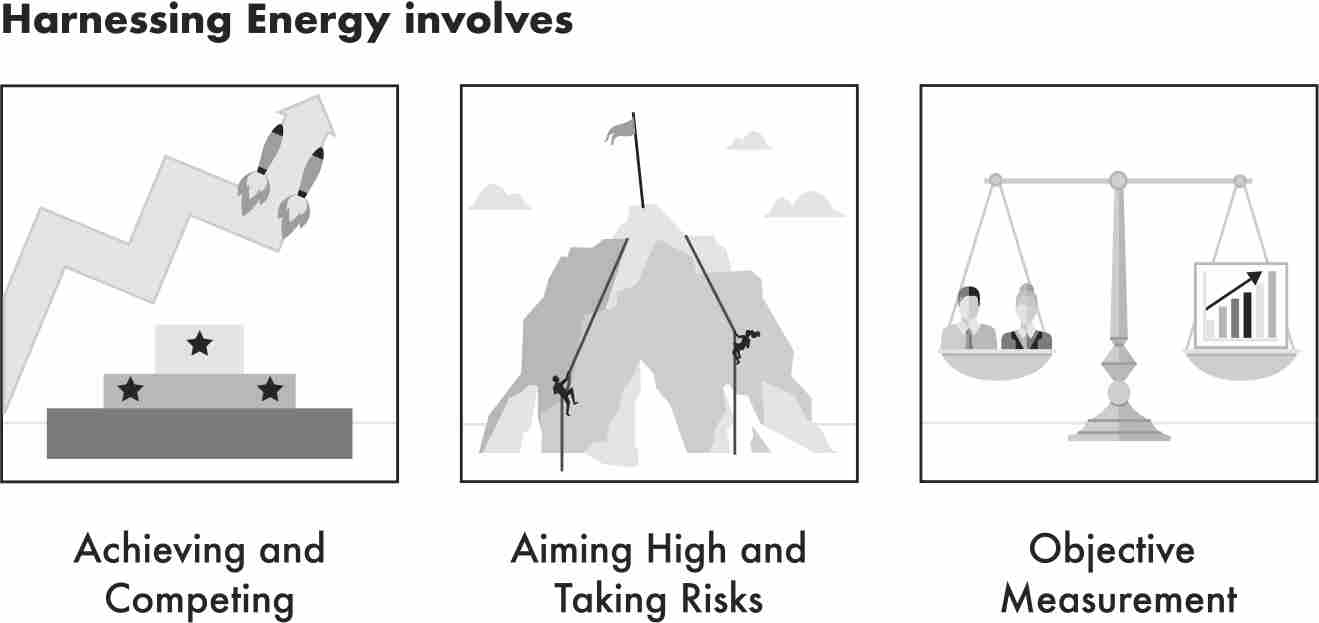

Satisfaction when measured against self is called an achievement drive.

Satisfaction when compared against others is called a competitive drive.

A Drive to Improve or a Drive to Win?

The behavioral manifestation of an achievement drive is almost identical to that of a competitive drive. Both individuals show incredible levels of determination and tenacity. They aspire to give their very best—to leave it all on the playing field. It’s almost impossible to tell them apart except at the final reckoning. Take note of the athlete finishing fourth with a beaming smile because they did well against their own standards, contrasted with the athlete coming second weeping uncontrollable tears. The signs are visible, and they reveal dramatically different emotional states. This is why using the term “competitive” without understanding the underlying psychology can be wrong and inappropriate.

If your assumption of competitiveness is unchallenged, it can lead to potential mismanagement of an individual. This could apply to the way you set goals and objectives and how you determine discretionary, performance-based pay. An employee with an achievement drive wants to be held to the standard of their very best prior performance. A person with a competitive drive wants to do better than everyone else in their role. The difference is subtle but significant:3

• If you set a goal for an “achiever” that is based on beating everyone else yet doesn’t build on their prior achievements, the goal could lack validity in their eyes.

• If you set a goal for a “competitor” that fails to establish them as first against their fellow employees, it might be considered a “soft” goal that is not worth pursuing.

And then there are those (fewer in number than you might think) who are both—driven by a strong sense of achievement and an unrestrained desire to come first. For these individuals, the competitive drive always takes precedence. For them, winning with a personal best is all that matters, and they need goal setting that clearly establishes these expectations. For such individuals, achieving a second-place finish is akin to being the first loser—not something to be celebrated. As a manager, you should be extremely careful before handing out rewards to employees with a competitive drive who fall short and come second. You might think you are motivating them, but deep inside, they find such actions condescending and patronizing. The best leaders know how difficult management really is.

How to Spot a Competitor

The competitive mindset is about a state of preparedness. Looking ahead to anticipate issues and events enables a competitor to optimize their response. This is why they tend to be very well prepared for meetings and think ahead to optimize their time and maximize their opportunities:

• Competitors, while waiting at a red traffic light, pay attention to cross-traffic stoplights in order to anticipate when theirs will turn green. Competition is therefore about a state of preparedness, maintaining a state of awareness that enables them to maximize all opportunities and to be efficient and effective in all things that they do.

• Competitors tend to walk just that little bit faster. As banal and puerile as this sounds, walking fast… and at least faster than others… is just one way competitors literally keep ahead. They tend to be early to meetings in order to maximize productive time. A competitor scratches their head at the sight of air travelers standing on a moving walkway in the airport. They see this as wasting time.

• Competitors reach their arm between closing elevator doors so they don’t have to wait for the next. There are only so many minutes in a day, and competitors don’t want to waste any of them.

• Competitors tend to count, and they use numbers as their standard of comparison. Competitors count the important business-tracking and performance numbers that matter, but they also play with numbers in their head all the time.

• Competitors who travel the same work commute by car each day hold a virtual stopwatch in their minds. They intuitively know how long it should take them to reach a specific intersection or landmark. Anything faster than the typical time feels good. Fall a little behind and it raises irritability by different degrees.

How to Spot an Achiever

If the competitive mindset is about a state of preparedness, with the individual ready to exploit any opportunity that presents itself, the achiever mindset is about a state of planning and sequencing. Achievers like to check off tasks and goals as part of a sequence of work activity.

• Achievers are serial list makers—checking items off their list builds satisfaction and further motivation. The list is everything, and as happy as achievers are at building their own lists, they don’t hold back from building lists for others, whether they want them or not. Satisfaction comes from striking things off the list. It feels good.

• Companies make personal organization tools for achievers. Whether planners or calendars, achievers appreciate tools that make list-building easier and more ubiquitous. Franklin Covey built an entire business empire devising planning tools for achievers.

• Achievers are well equipped to plan the various stage gates in an implementation plan and drive themselves and colleagues to meet each of these requirements. With minds like a Microsoft Gantt chart, achievers forever mull over work sequences and how to build a plan that defines the critical path and coordinates complex activities that can be checked off en route to the outcome.

• If there are twelve steps in their implementation plan, then achievers will methodically and expeditiously work through each step in the sequence, checking off progress as they go. This kind of work can provide meaning for them.

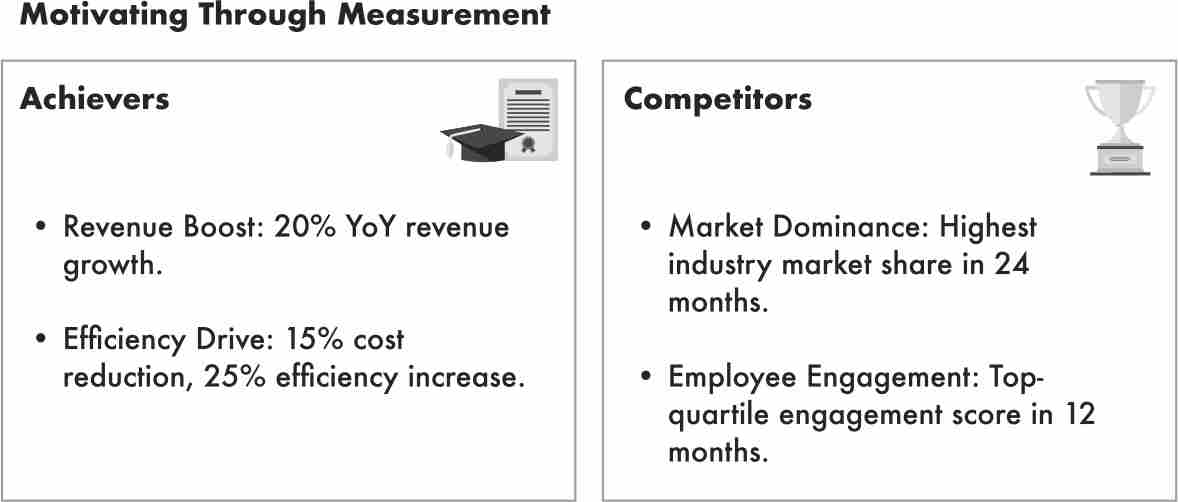

Motivating Achievers and Competitors by Measurement

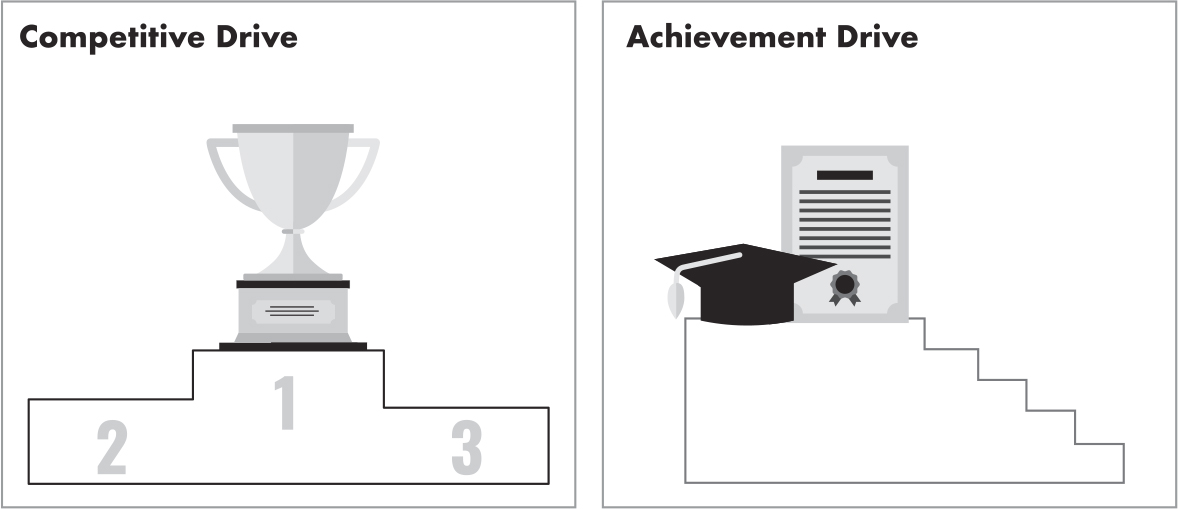

One differentiator between an achiever and a competitor is how measurement factors as a motivator. For an achiever, it is incremental and plays out on a scale. For competitors, it tends to be binary—win or lose. This fact highlights the most appropriate management tactic for getting the best out of each:

• Create a scale (ladder, if you will) for achievers. Use descriptive or numerical criteria and define a clear outcome. Achievers particularly value internal measures where they are able to compare their current achievement against what they did at a prior time.

• Draw a clear winning line for competitors. Competitors demand measurement, which implies numbers and scales. Competitors like to see how they are doing in comparison with their peers, but they are also driven by external measures if they are available, such as industry standards that they can beat or competitor companies whose published performance can provide a huge incentive.

The performance management implications are clear, and we have often seen simple, progressive goals working for achievers but disincentivizing competitors.

“Who Sets the Higher Goal, You or Your Manager?”

Managers would do well to ask this question to understand who on their team is a real competitor and to manage them accordingly. It’s rare to meet a strong competitor who doesn’t look at the goal their manager sets without thinking they can do better. Their sense of accomplishment is influenced more by their achievement of the higher goal. Some of the best leaders we have ever studied see their goals as starting points—the minimum that should be delivered—and are driven by a moral and ethical obligation to meet and exceed that minimum.

It’s worth reflecting on the fact that there are many more achievers than real competitors, but we tend to think the opposite because every time we see someone displaying drive and tenacity, we assume that they are competitive. Correcting this basic error is key to effective leadership and management.

Driving Blind at High Speed

I learned an important leadership lesson in 1988 when I was attending a development program at St. George’s Hotel in Llandudno, North Wales. Thirty senior educational professionals gathered to be taught—and then to apply their learning—to understand how to construct educational timetables that enabled the best learning for school students. Complex scheduling has always fascinated me, and I was excited about this program. I was the youngest participant by some margin, and it was clear to me that I was in the presence of much more experienced professionals. It didn’t unduly concern me.

To give you an idea of the task, think about the last airline flight you took and all the planning that had to go into achieving it successfully. The coordination of all the elements—aircraft, crew, fuel, passenger refreshments, gate crew, baggage crew, and so on. Then extend your thinking to an entire airline company and the complexity of scheduling everything that must happen to ensure that your aircraft is where it should be before it departs and where it goes next after you disembark. This schedule must be built months in advance and be sufficiently flexible to be varied due to bad weather or aircraft maintenance and breakdowns. It’s the kind of complex mental work that I love, and this was the work facing me in Llandudno.

Instead of aircraft, we had classrooms of various sizes that could accommodate some groups but not others. Some of these rooms contained specialist equipment and resources that could be scheduled for only one purpose, such as science labs. We had teachers with different levels of expertise, some of whom taught in only one classroom while others were itinerant, a bit like having flight crew who are qualified to fly some aircraft but not others. Those teachers needed some “free time” scheduled across the week, and so on.

It was a five-day course, and on day four, we were given a fictitious institution and told all the constraints we would have to manage. Our test was to build a functioning timetable for one grade level. I thought this was too easy a task and committed to building the schedule for the entire organization—all seven grades (K5 through K12). In the time it took me to do this, some of my fellow attendees were still struggling to complete the one grade level they were assigned.

We were allocated six hours, and I finished with a flush of pride just before the clock timed us out. The supervising professors—most of whom were mathematicians—conducted their evaluation in real time with the whole class attempting to learn from their identification of mistakes or suggestions of how to improve the submitted work. As the group moved to my work, I realized that I had made a huge error just as the professor pointed at my submission and asked his question. I was so disappointed in myself. The mistake was significant, as it affected the entire schedule and meant that the work I had done on the grade we had been required to complete was also in error. I failed the assignment.

My competitive drive, my self-confidence, and yes, my arrogance, were my downfall. Rather than meticulously checking and cross-checking my work, pressure testing each sequence for error, I just blasted ahead, too sure of myself and too reliant on my natural intelligence and knowledge. I learned about the need to slow down, to be more modest in my goals, to curb my ego, to better appreciate that not every task is a test requiring me to prove myself. To show a little more humility. It was only after the accumulation of many similar examples when studying other leaders that I realized that the need for this lesson was more general and that many leaders hadn’t yet learned it. It was a painful experience that I vowed never to repeat.

SENSE OF VALUE AND SELF-WORTH

Research Definition: High levels of self-confidence, self-assurance, and self-efficacy can push leaders to set high expectations for themselves and others.

The drive to achieve or compete isn’t the only source of energy that can push a leader to succeed. Some individuals are driven by a sense of importance and significance—a belief that they can solve the big problems and achieve a level of success that lies just beyond the reach of others. These leaders tend to volunteer for the toughest assignments, in the most visible situations, where the potential for failure and reputational damage is extremely high, yet they are energized by a sense that they can succeed. We find that many competitive leaders are also strong in this trait, and the overlap should need no explanation.

The reason for such high levels of self-assurance is that these leaders have earned it through past success and achievements. They can recount multiple examples of having applied themselves to the most difficult problems and come through successfully. This fuels their belief that they can solve future problems. It shouldn’t be too surprising that individuals who exhibit these characteristics earlier in life progress to positions of authority and leadership later in life. In his book True North: Discover Your Authentic Leadership, Bill George described in detail the early life experiences of many leaders who were thrust into leadership roles as young as seven years old.4 When asked to describe when they first realized they had significant leadership capabilities, the vast majority talked about early school experiences that became more visible and accentuated throughout their teenage years. This isn’t to claim that leadership is deterministic but rather to note that many of the most self-assured leaders exhibited these characteristics and traits at a young age.

Developing a Positive Self-View in Early Adolescence

“What Advice Would You Give to Schools Trying to Develop Leadership Qualities in Young People?”

In 2010, I spoke to an audience of school superintendents who asked this very question. Develop their self-confidence was my reply. Help them discover their strengths and capabilities, and then give them increasing opportunities to excel in those areas and affirm their achievements. There is no more important role for teachers and parents than to increase the confidence of young children and to affirm their capabilities to others.

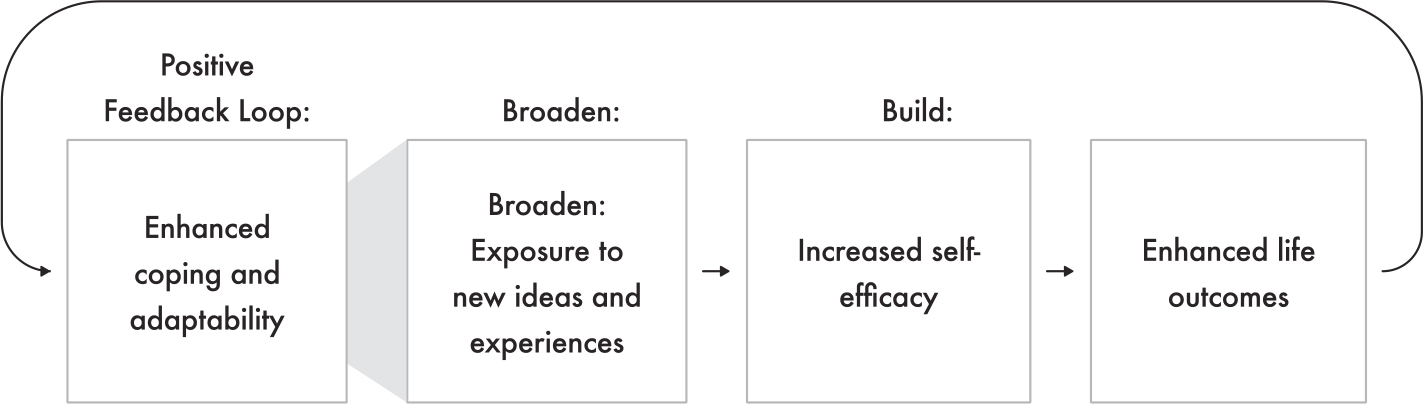

Psychology researcher Barbara Fredrickson developed the “broaden-and-build” theory to describe her discovery that accentuating a young person’s success in a specific area of achievement led to improvements in somewhat unrelated areas of activity and that encouraging more of this success created even more peripheral benefits.5 A child who excelled in drama, for example, and who was affirmed for this capability and encouraged to build on their accomplishments could see a significant increase in their math scores in a way that was strongly correlated but clearly unrelated.

Fredrickson’s research also established the pervasive influence of a negative focus. If you apply focused criticism to areas where young people don’t do well, their performance in previously strong areas diminishes. Just as the beneficial focus on boosting self-esteem and self-confidence created a positive compound effect, the reverse created a broad and negative effect. Too little of her work has permeated modern management practice, and too often managers find it easy to catch employees doing the wrong things rather than catching them doing the right things and celebrating by affirming these.

If we take Fredrickson’s research one step further, one prediction we could make is that highly assured leaders with a strong track record of success should be more likely to contribute effectively outside their area of competence and expertise. This is exactly what we find. Leaders fueled by a strong sense of self-efficacy are much more likely to contribute positively to areas unrelated to their specialist domain. The idea may seem counterintuitive, but helping to increase a leader’s sense of efficacy and affirming their contributions may be a potential solution to demolishing the silos and trenches that keep people apart and drive more defensive and insulated functioning.

Owning Your Strengths

“What Do You Do Better Than Just About Everyone You Know?”

We ask all leaders this question, and the responses tend to be underwhelming. Even allowing for humility, and the tendency for people to play down their capabilities, the lack of specificity in response is stark. People genuinely struggle to talk about the things they do well and better than most, which highlights how poor a job companies do at describing a person’s worth and establishing their expertise and value.

It is remarkable how quickly, when asked about their strengths, people pivot to describe a litany of weaknesses and failures. This is more than being self-effacing—it’s a denial of contribution, and it has a strong cultural underpinning. We play down our abilities in order to avoid appearing as though we are the smartest person in the room, but this situation isn’t in balance. It is heavily weighted toward a negative projection of self, and this is something we need to work collectively to address.

We often encounter people who, without really thinking, declare that a person’s strengths can become their greatest weaknesses. It’s ridiculous. Not only are people reluctant to own their strengths, but we also have a whole series of psychologist blowhards and cheerleaders—who should know better—taking the little positive reflection individuals have of themselves and turning it back on them as a potential negative detractor. A 2009 Harvard Business Review article by Robert Kaplan and Rob Kaiser titled “Stop Overdoing Your Strengths” (and their subsequent book, Fear Your Strengths: What You Are Best at Could Be Your Biggest Problem) is Exhibit A in this misguided characterization.6 Oh, how psychologists like to revel in misery. We discussed this tendency in the first half of this book.

“What Do You Think Will Help You Improve the Most: Knowing Your Strengths or Knowing Your Weaknesses?”

Gallup has been asking this question for decades, and most people believe that knowing their weaknesses is the key to their success. This is completely wrong. Too many practices in organizations, from annual reviews to performance management, reinforce this negativity and act to suppress self-confidence and assurance. It requires very special individuals to be able to rise above this and create the impact they know they can achieve.

If companies and leaders are serious about drawing the best out of every employee, they need to build each individual’s self-confidence. The best leaders do this intuitively. They celebrate the success of others. They position others so that their contributions shine. They distribute recognition and build people up. It is a relentless focus that weaker leaders regard as optional.

MEASUREMENT DRIVES GROWTH

Research Definition: Growth requires challenging goals and the clarity that comes from objective measurement in the pursuit of those goals. Growth is more the consequence of having the most Talented people in roles that fit them than of the products and services they sell or manage.

Some of the highest-performing leaders we’ve ever studied are nearly always driven by measurement that encompasses the breadth of their work contribution and value, and they tend to create these measures despite their organizations, not because of them.7 These leaders look at their world through a dashboard that indicates how progress to the goals that are set is being tracked. It is a mindset that sets them apart from the vast majority of leaders, who see their value in terms of task and activity completion. To use our power source metaphor, their dashboard measures every critical activity and function in real time. Without these dials, leaders are “flying blind.”

There are two elements that seem to be strong measurement principles for objective measurement and performance-oriented leaders:

First, they measure a broad range of indicators that capture how value is created beyond just financial terms.

Second, they use their dashboard as a base for setting goals that others believe might be just out of reach—the true definition of “stretch goals.”

For these leaders, the drive to objectively measure performance is the essential ingredient in how goals should be set and how individuals should be held to account. They know that every employee in their organization needs to know whether the work they are doing this year is measurably better than the work they did last year or quarter to quarter, month to month, week to week, or day to day. Armed with data, high-performing leaders understand the diminishing returns that come from less Talented employees and focus their efforts on building teams where highly Talented individuals can contribute their best work. When this occurs, growth is the logical outcome.

Manager Ratings Are Not Measuring Performance

High-performing leaders establish objective measures of performance that help them evaluate the contributions of their people and whether their business is growing in meaningful ways. When we talk about “objective measures” with respect to how people perform, it’s important to understand that this discussion has nothing to do with the manager ratings typically filed during the dreaded end-of-year performance reviews.

A mistake too many companies make is concluding that because one important aspect of a person’s role is difficult to measure, then it makes an objective evaluation of their overall performance impossible. Very quickly, rather than doing the hard work we are about to outline in this chapter, companies default to a proxy performance measure—manager ratings. These are extremely problematic—so much so that an increasing number of leading companies are removing them from their performance management systems. We agree with these companies.

Before digging into the details of manager ratings, we should point out that top-performing managers and leaders dislike them and generally find them demotivating. Companies that do things that annoy their best performers should stop and take notice, but they persist in a state of denial and rely on the good nature and professionalism of top-performing managers and leaders to keep them quiet and playing the game. In most cases they do, but quite often they don’t and silently leave organizations in “pursuit of other opportunities.” We wish more would vote with their feet in this way.

Why do we state that manager ratings are a poor proxy for objectively measuring performance? The main reason is that in too many credible studies, manager ratings have an extremely weak or inverse correlation to the outcomes that are required—higher manager ratings don’t relate to higher performance.8 The main reason is that when managers are rating their employees, they are not accurately scaling their performance; they are scoring the likability of the employee. Companies that describe manager ratings as “performance ratings” deserve to be sued for false claims.

To repeat… companies should be strongly advised not to engage in practices that annoy and/or disengage their highest performers. The very best leaders know this, and as strongly as they might advocate for change to a more objective performance measurement, the HR systems in most companies (the endless paper chase of form filling and box checking) operate like a sponge and suck the life out of people, leaving these leaders to covertly develop commendably creative acts of subversion. If these leaders were to seek crowdsourced funding to support their efforts, we would be their biggest contributors. They might be fighting a losing battle, but it’s one they can’t afford to give up. Here are some research findings that have contributed to the move away from manager ratings:

• Managers intentionally distort their ratings of employees for three key reasons.9

* Avoiding the negative consequences that could result from a more accurate rating motivates managers to produce inaccurate (usually inflated) ratings—it avoids them having to have a potentially difficult conversation with a low performer.

* Managers wish to conform with organizational norms. For example, some companies require that no more than 20 percent of employees receive the highest ratings (or even specify the percentages for each score from 1 through 5). This also applies to negative scores when, if the manager gives a person a score of 1 (the very lowest rating), the company might ask why that employee is still working for the company. Thus, managers know not to give anyone a score of 1 in order to avoid that difficult conversation.

* The self-interest of a manager could lead them to distort their ratings. Managers might believe that evaluations of their own performance are related to how they evaluate the performance of their team members—higher scores awarded to their team members might be seen to reflect positively on perceptions of their leadership.

• The way managers rate their employees is more a reflection of their own thoughts and beliefs about work performance than an objective evaluation of how the person being rated is actually performing.10

• There is a weak to negative relationship between manager ratings and objectively measured performance.11 A research paper from 2002 concluded, “There appears to be little evidence that impression scales (manager ratings) predict job performance.”12

• A 2003 research paper established that how strongly a manager rates an employee on a work characteristic depends on how well the manager also shows competence in that characteristic.13 The same research paper showed that managers who displayed high discretionary effort were much more likely to rate highly employees who also showed high discretionary effort.

• For performance ratings to be accurate and credible, managers should use the full range of scores, yet they rarely do. A 2011 research paper found two biases that prevent managers from using the full scale.14 One is “centrality bias,” which accounts for managers’ tendency to compress their ratings, typically to 3 scores—3, 4, and 5 on a 5-point scale where 5 is high. This bias was far more common than “leniency bias,” which is the tendency of managers to inflate their ratings by a factor of 5.64, possibly to avoid some of those difficult conversations we highlighted in the previously mentioned first point.

• We found through our own research that the more socially sophisticated and positive an employee is, the greater the likelihood that their manager will rate their performance higher. Employees who might ask difficult questions or not show immediate compliance with their managers’ wishes invariably receive lower ratings despite often being regarded more broadly in their organization as outstanding performers. We describe this as an “ease of management” problem, for obvious reasons.

• If manager ratings accurately reflect actual performance, then the aggregate of all ratings in an organization should closely correlate to that organization’s financial performance. However, they don’t. In fact, when aggregate manager ratings are compared, most companies fall in the range of 4.1 to 4.3, essentially the same across all companies, yet those companies show financial performance across a much wider range. The logical explanation is that even though we call them “performance ratings,” the ratings have almost nothing to do with performance.

Sometimes We Find an Inverse Correlation

Our partnership with a large US-based retail organization revealed the fundamental flaw in pretending that manager ratings are an effective proxy for performance measurement. We studied all 132 of their retail stores and ranked and then quartiled them by their two main performance measures—conversion% and $spent per customer. Even though we were in possession of actual performance data, we asked the twenty-one district managers (DMs), to whom all store managers reported, to rate the stores based on their performance.

The DMs all had the same data we had. A cursory glance at this ranking would provide all the information they needed. What could possibly go wrong?

• The stores occupying the second quartile in the ranking received the highest average performance ratings by the DMs.

• The third quartile received the next highest rating and the fourth quartile the next highest.

• The lowest-rated stores were in the top performance quartile, and the overall correlation was slightly inverse when it should have been emphatically positive.

It was a puzzle. When we dug into the details to find an explanation, we found that the managers of the top-quartile stores were too much of a handful for the DMs to deal with. These store managers were pushy, demanding, and uncompromising in their relationships with the corporate organization. They used their insistence and assertiveness to secure benefits for their stores in terms of inventory and SKU availability as well as early access to promotional campaigns and employee training.

The DMs, when rating stores, weren’t rating performance; they were rating ease of management. Their ratings were a reflection of themselves, not the store managers they were supposed to be evaluating. This was one of our first exposures to how weak managers can destroy organizations and why good people join organizations but leave bad managers.

It is for these reasons, among others, that many companies have stopped the practice of manager ratings.15 We applaud them. Effective leaders often don’t need confirmation from credible research studies to inform what they intuitively know to be true… but having research-based findings that expose the many problems with manager ratings is important in educating organizations, and particularly less performance-oriented leaders.

In this book, we also describe how the presence of positive characteristics in a job evaluation can influence managers to appoint those possessing strong relational skills and more favorably view candidates who are generally positive and upbeat over those who do not exhibit these characteristics. We not only have manager rating bias, but we also have employee selection bias—they are different sides of the same coin, and those seeking to address demographic imbalance in their organizations would be well-advised to evaluate their own manager biases before embarking on what could be a futile program of change.

Our conclusion—and this will be upsetting for some to read—is that organizations that rely on manager ratings as a proxy for measuring real performance are doing the opposite of what they claim. They are inherently lazy organizations.

Understanding Growth

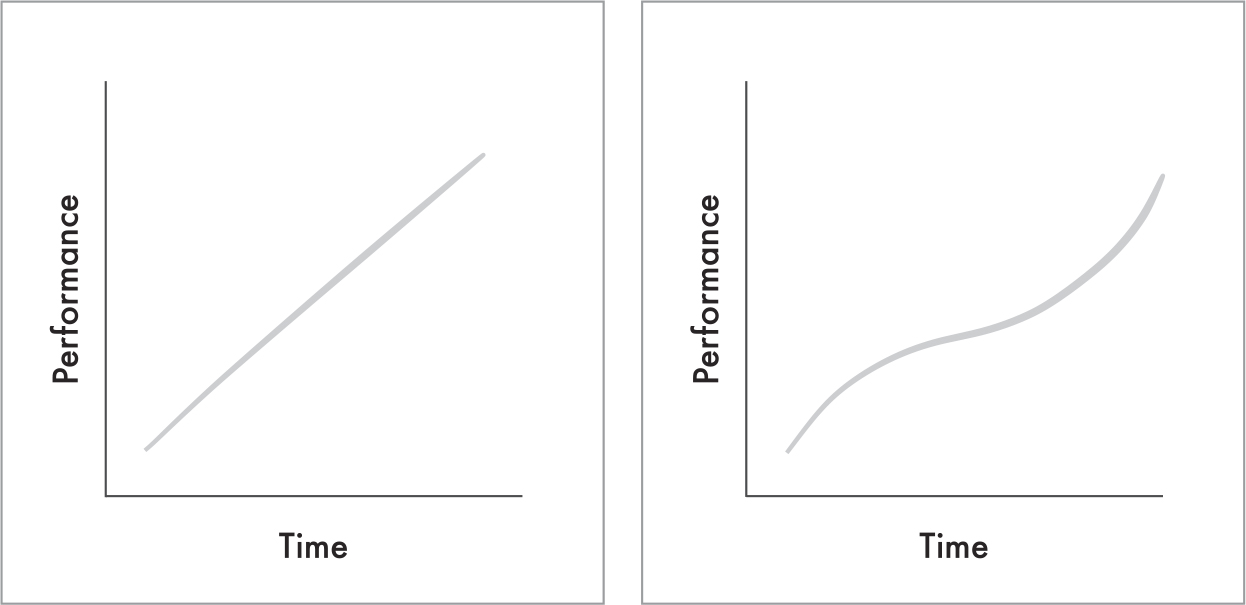

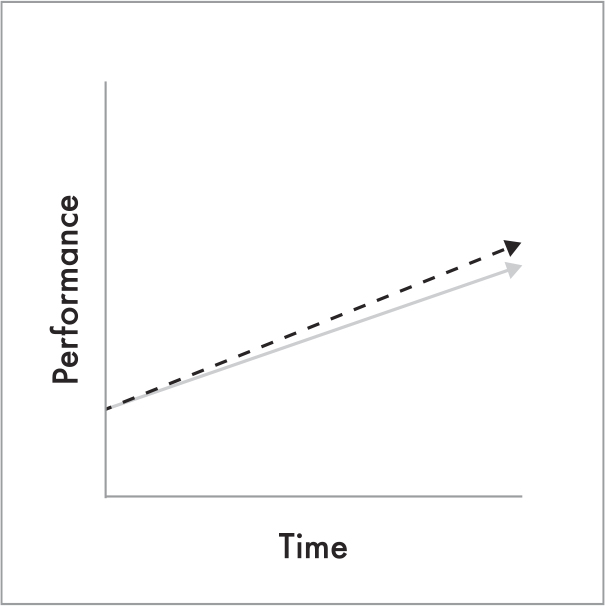

Consider the two following graphs. They were created by two different leaders who were provided with the matrix and asked to “draw growth.”

We’re often invited to discuss ideas about performance management and growth orientation with groups of leaders. When we do this, we nearly always direct some members of the audience to a whiteboard and invite them to “draw growth.” Now, there is no scale to this graph. Although the “Time” and “Performance” labels are understood, there are no objective measurement intervals or definitions. We are simply trying to understand what a person thinks when instructed to draw growth.

It’s not a difficult task, but people approach it with some doubt and hesitation—no one wants to look foolish, and they are waiting for the catch. Usually, everyone succeeds in the task. Any line that starts low and ends up higher over time clearly represents growth, but each person approaches this in a slightly different way. Some people draw aggressive lines with a steep upward curve. Some draw wobbly lines that reflect the reality that growth over time isn’t always consistent or linear. Some draw very shallow curves, perhaps in recognition that growth is hard to achieve.

The reason this exercise is important is that, alongside a drive to objectively measure performance, high-performing leaders are driven to achieve growth—they have an extremely strong growth orientation. But for too many leaders, their definition of growth lacks rigor. Boards and CEOs recognize this problem and attempt to define it in more objective ways. For example, if a company is to be regarded as a “high-growth” organization, it needs to deliver double-digit revenue performance consistently over time. This is a powerful statement, but only if the market is growing at a much slower pace.

Companies that struggle to achieve market-beating revenue growth look for other ways to describe their success, and the default is usually EPS. This becomes attractive when revenue growth is challenged because an internal focus on cutting costs is a little easier to achieve. Each company places a different emphasis on various financial measures to determine growth rates. Our general advice is this—if revenues outstrip prior performance while also exceeding the market, then that company can legitimately claim to be growing.

Highly Talented People Drive Growth

For high-performing leaders, the answer to “growth” questions is always people. Those who think it might be a combination of product, price, and service, important though they are, are completely missing the point. Every world-class element of your product/service offering will fail in the hands of a weak sales rep. Weak reps have a gift for making outstanding products sound tedious and destroying the idea that your company might be easy to do business with. It is the centrality of people to growth that unlocks the potential of successful organizations.

This doesn’t mean that all people contribute equally. Consider how you would answer the following question:

You are leading a sales organization, and in the beginning of the fourth quarter, you are struggling to achieve your quota. In order to increase sales and achieve your annual quota, where will you apply the greatest focus?

• Your bottom-performing sales reps (who clearly have a big gap to close)

• Your top-performing sales reps (most of whom are already ahead of their quota)

Let’s look at another question that will immediately reveal whether you got the answer to the previous question right or wrong:

All other variables being equal, which of the following would most likely result in higher growth?

* Trying to improve the performance of bottom performers

* Trying to improve the performance of top performers

If the answers aren’t now obvious, this book wasn’t written for you. Yet, for many leaders, this scenario seems counterintuitive and contradicts how they spend much of their time. Jack Welch made this precise observation in 2016 when he stated that “most managers find themselves in countless productivity-sucking meetings and sidebar conversations about underperformers.”16 We often attend leadership team meetings and talent reviews where leaders complain openly about how much of their time bottom performers consume. It’s almost as though these leaders see wasted time as a necessary evil—it isn’t.

Variable Talent Levels Impact Performance

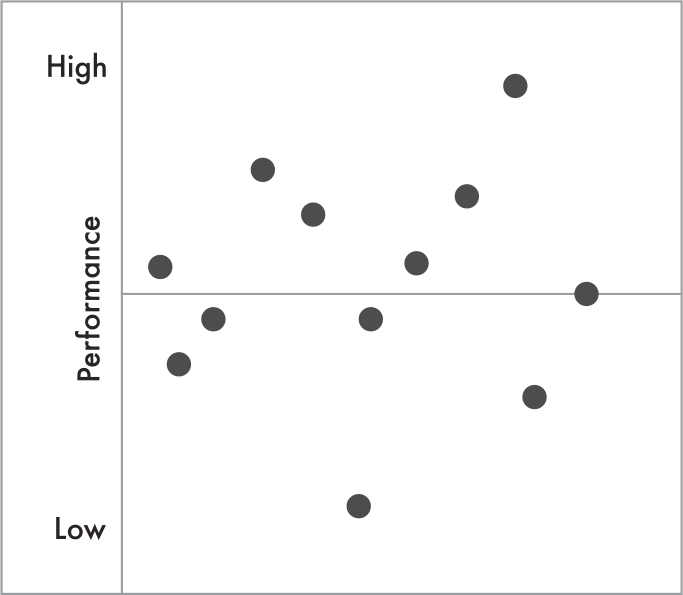

For leaders who expend significant energy coaching bottom performers and rolling up their sleeves to ensure that commitments are met, the cumulative impact on the overall performance of the team is clear. Let’s explore an example by looking at a hypothetical team with twelve members whose performance is plotted on an array.

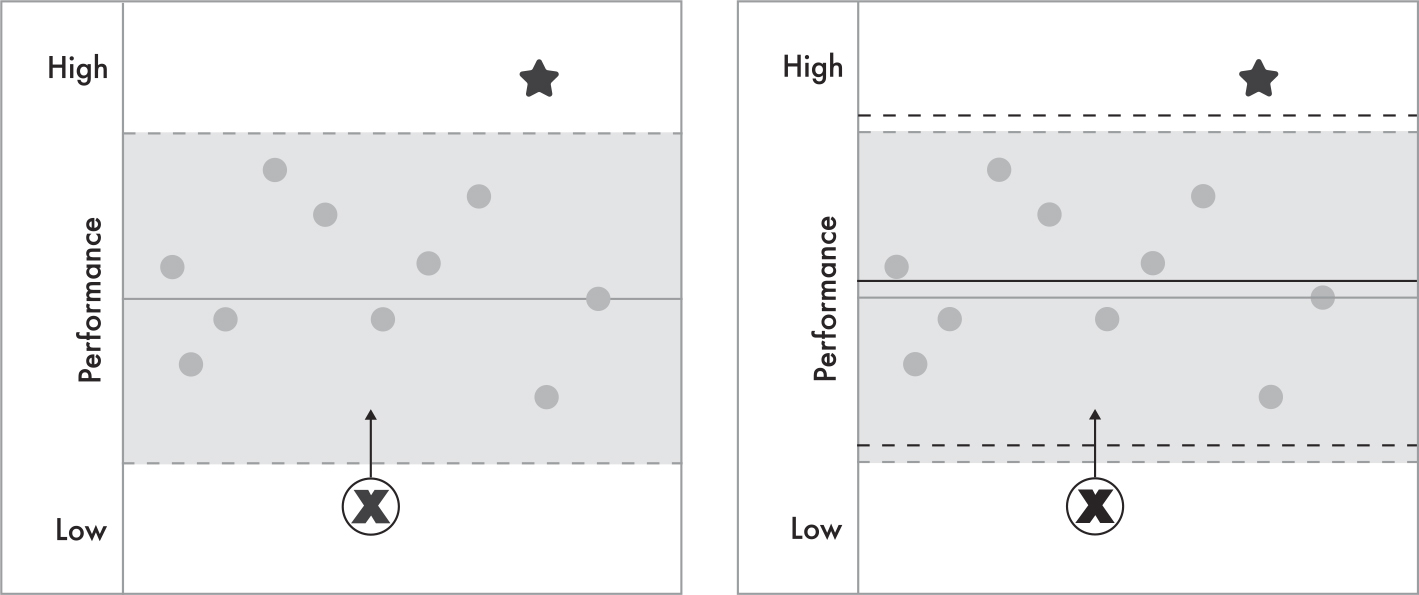

There is a range of performance in every team that reflects the varying level of Talent across all individuals. The horizontal line represents mean performance. Here, we see that five team members fall below this line, six are above it, and one is directly on the line. How do leaders and managers usually regard a performance array of this kind? First, leaders don’t regard all individuals as equal. They make choices about where to spend their time and whom they want to see improve.

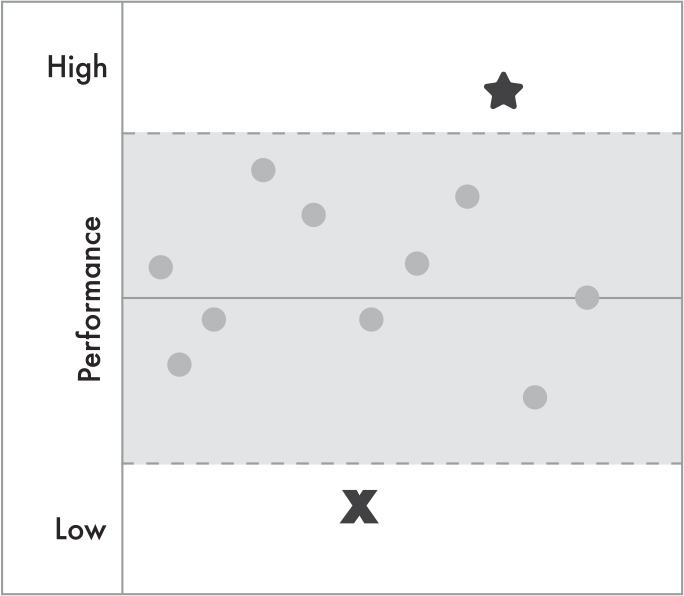

The shaded area around the mean represents an invisible band of “tolerance.” Individuals performing just above or just below the mean don’t tend to stand out. Their performance isn’t outstanding or causing any obvious problems, and they get less attention from their leader as a result. The width of this tolerance band varies a little from leader to leader, but it is typically broader rather than narrower. In this example, one team member falls outside this “invisibility band” on the positive side ( ) and one on the negative side (

) and one on the negative side ( ). They are outliers, and, more importantly, they are visible.

). They are outliers, and, more importantly, they are visible.

How might high-performing leaders look at this information in comparison with average- to low-performing leaders? A well-publicized 2012 study by Robert Half suggested that managers spend about one day each week trying to coach and improve poorly performing team members.17 But this research conceals a much more important finding—that 89 percent of leaders are predisposed to focus (and spend the most time) on poor performers, and only 11 percent of leaders are predisposed to focus on top performers. Top-performing managers and leaders overwhelmingly focus and spend more time on coaching and developing top-performing team members, as we discovered from our database of over fifty-eight thousand leaders.

Focus on Improving Poor Performance

The interesting question is what the impact of this time focus achieves. If 89 percent of managers are predisposed to coach poor performers, does it have any impact? If so, is this an acceptable return on their time investment?

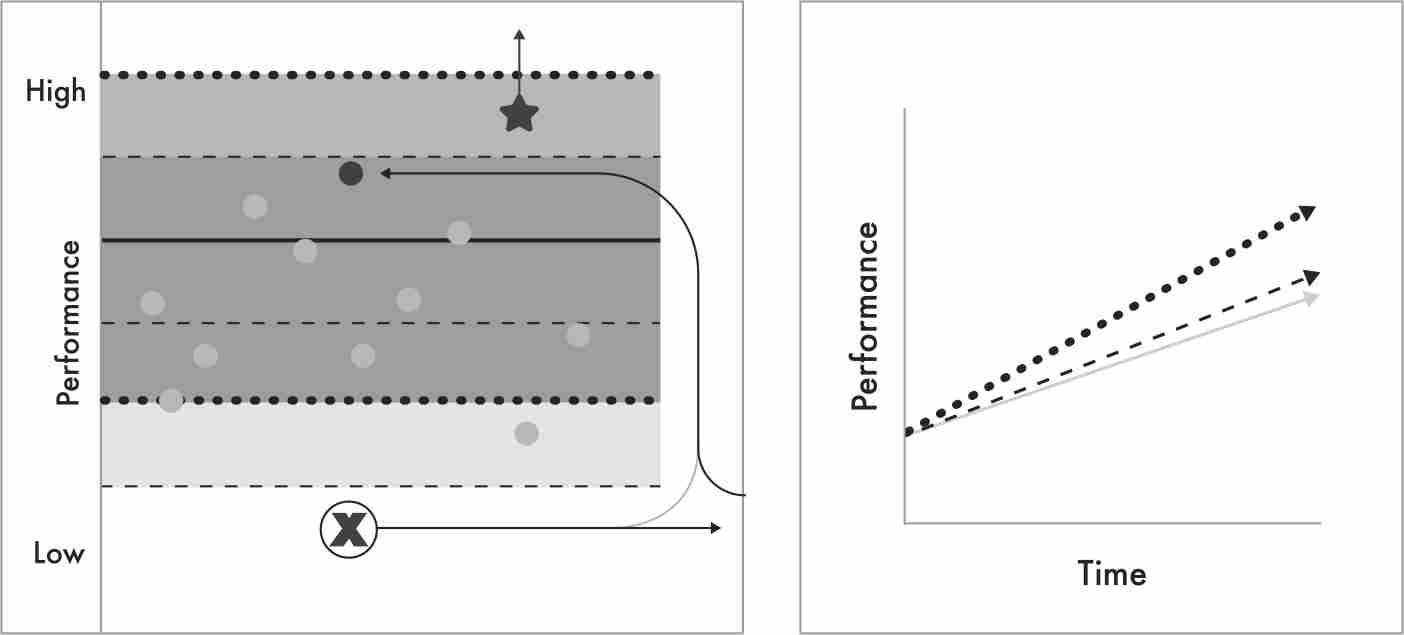

When we interview leaders who focus most of their time on bottom performers, they often claim that they are trying to turn these weak performers into top performers. The reality is that they are trying to raise these employees’ performance to the point where they occupy the invisible band we previously illustrated, and then they can stop worrying about them. Put simply, they want the problem to disappear. Moving them up a little into this range solves the manager’s performance variance problems.

Calculating the impact of this “improvement” on the overall team performance (assuming all else remains the same) shows a negligible gain. The improvement in performance of that one individual barely impacts mean performance, but at least the improvement is positive. If 89 percent of managers in a company achieve this degree of performance improvement, what might the collective company benefit be? Returning to those “growth” curves we highlighted earlier, we can transfer the expected results—and they show a minimal improvement.

Before we begin to argue that all progress is good, we must recall that this is the product of managers spending 20 percent of their time, week after week, on a single task with diminishing returns. This explains why so few companies can generate market-leading performance that separates them from their competitors. Rather than expect significant year-over-year growth, companies recognize the reality of their limitations, and phrases like “We win some, we lose some” justify their relative mediocrity.

Focus on Improving Good Performance

How different might these results look if more high-performing, growth-oriented leaders were the norm in organizations? First, we should point out that these leaders don’t ignore poor performers. They apply minimal time working out whether the required amount of improvement is even possible, and they quickly reach the decision that in most cases, it isn’t. They would rather act on this reality quickly to gain more immediate and sustainable performance gains with a higher-performing employee.

Poorly performing managers and leaders take too long trying to improve the poor performance of some team members and often never conclude that they should be terminated and replaced with more Talented individuals. Top-performing leaders act with a much greater sense of urgency, often bringing this focus to a close within three months. But even with a decision of this kind pending, they still spend most of their time coaching and developing those who have the capacity to achieve world-class performance.

In this example, the bottom performer exits from the company and is replaced with an individual whose Talents are a much better fit for the role and who has a greater capacity to perform. The focus on coaching and developing our high-performing outlier also contributes to better performance outcomes. A focus in this direction shows a significantly greater and more positive impact on the overall performance of the team.

If more highly Talented, growth-oriented leaders were contributing performance improvements of this kind, we would see much different growth trajectories at the organizational level. The fact that this isn’t happening tells us that companies employ too few leaders with this focus and that organizational performance management practices are too often rooted in popularity contests. In these companies, the excellent outcomes of high-performing leaders are easily canceled out by the mediocre outcomes of weaker leaders. Not surprisingly, those at the very top of the org chart lack the vision, awareness, and capacity to change things. Their organizations are a direct reflection of them.

Goal Setting and Incentives That Drive Performance

High-performing leaders regard their goal as the minimum performance expected. This means that in sales organizations, everyone is expected to achieve their quota because the quota is the minimum expected. It logically follows, therefore, that financial and other rewards kick in at that level. The incentive should always target achieving quota as the first step in the reward process. But for organizations to grow and become more competitive in their market, incentivizing sales reps to perform above quota is required, and organizational leaders are best advised to spend their time and effort on determining how to build an incentive structure that drives sales reps to exceed the minimum expected by the quota.

Sales leaders who lack vision and who fear a negative backlash and possible sales rep attrition are the single biggest impediment to this change. Rather than setting quota achievement as the minimum level at which performance rewards kick in, they dispense emotional therapy and support and are happy to put their arms around sales reps who tried hard but didn’t quite make it. They do this by granting financial rewards to reps for coming in just below quota at year end. This really raises questions about what “performance” means and the bar the quota represents.

Rather than building a reward ladder leading up to the quota, high-performing leaders use the quota as the bottom rung and build the ladder above it. It’s a complete shift in mindset from what is typically seen in organizations.

The organizational benefit of this approach is that the overall company performance goal is more likely to be achieved or bettered, as reps exceeding quota hopefully outnumber those who don’t. This almost never happens with systems that reward mediocrity. As you think through the implications of this approach, the idea of rewarding below quota achievement becomes challenging. If you want a high-performing organization, you won’t build it by setting goals that reward average or poor performance—you will be much more likely to succeed if your expectations and management of performance require the achievement of exacting goals with strong incentives in place for those who exceed them at each level and with rewards that deliver exponential benefit.

Measuring Roles That Are Hard to Measure

Sales can be counted, plotted on a graph, and compared over time and between individuals and groups. Not only can quotas be set and used to drive performance, but absolute and percentage growth over time can be calculated. This objectivity is harder to define in roles that aren’t typically measured by numbers or where performance is difficult to plot on a graph. High-performing leaders don’t use this as an excuse, and we have seen some inspired and creative practices to address this problem.

The interesting thing about performance levels—even in sales roles—is that we can describe them with reference to criteria. These criteria can be descriptive of specific levels of performance. With thought and effort, it isn’t difficult to describe poor (or great) sales performance by developing the criteria that indicate poor (or great) performance. This is true for all roles. Rather than just using timeliness or completion as binary output indicators (which typically ignore important qualitative criteria), high-performing leaders do the hard work of defining performance-level criteria and building a progressive, descriptive account of how performance should start with the minimum achievement expected (the goal) and progress to top performance. This scale or ladder might comprise three or five steps with the criteria becoming progressively harder to achieve at each level.

Starting by defining goals as “minimum acceptable performance” has the potential to transform the way leaders think of organizational success and growth, and moving toward this way of working is sure to create short-term casualties. Some people, to put it simply, won’t make it. This inevitably happens when organizations shift toward a performance-based culture. Some employees won’t be able to operate successfully with these raised expectations. High-performing leaders know this is not an excuse or a credible argument against change, but others will use it as a reason to try and prevent it. Those who have the most to lose from shifting mindsets about what is possible are below-average and poor performers, and they will kick and scream against change for as long as you allow them to.

The reason more poorly performing organizations are weak is because they have low Talent levels, and they are scared that raising performance expectations will lead to high failure levels, disengagement, and even higher turnover. They have this argument completely wrong, which is why they struggle to improve. You need to set the bar really high in order to expose the problem. Only by setting the bar so high will organizations understand who their great performers are.

Once these employees are visible and empowered, companies should build their recruitment policy around finding more of these Talented individuals. The difference between companies that initiate this journey and the failing organizations that don’t is in the quality of the turnover. In aspiring companies where great leaders take steps to raise the bar and drive performance, poor performers leave and great people can’t wait to join. In poorly performing organizations where weaker leaders are scared of the implications of change, poor performers feel secure and good employees, who join in error, quickly and quietly leave.

WHAT REALLY MATTERS

High-performing leaders are driven to succeed in different ways. Coupled with the direction-setting Talents discussed in the previous chapter, they are a formidable presence and force in organizations:

• For some, their self-starting nature might be the consequence of a strong internal drive to achieve or a more external focus on winning.

• Their success may be bolstered by high levels of self-confidence, self-assurance, and self-efficacy.

• The very best have objective measures of performance and the focus on Talent and growth to bring this about for the benefit of the company.

High expectations of outcomes are how leaders create performance and growth. You may be a leader who leads through an infectious motivation to perform if

• you have a knack for seeing the upside in most situations;

• you are never satisfied with your achievements and look to raise the bar even higher;

• you create scorecards and dashboards that drive you to be number one; and

• you are comfortable with risk and relish your role as leader in the most difficult situations.

Leaders need to apply objectivity to determine what opportunities have the largest upside—this applies to the business opportunities you pursue (and which ones you decline) as well as the people in whom you invest the most time. These questions can help ensure that your drive and motivation are focused in the right direction:

• What is the minimum level of performance that you are prepared to tolerate? Set your goal higher than this level.

• Nearly everyone knows the difference between good and bad. Define for every employee in every role the difference (using numbers or descriptive criteria) between the minimum expected and what constitutes good and excellent performance.

In the next chapter, we address one of those aspects of leadership without which change is very difficult—the capacity to challenge and influence the thinking and actions of others. To the disappointment of every motivated and self-driven leader, despite their very best efforts, they can’t do it all on their own. They must bring others along, preferably on the same journey, in the same vehicle, heading in the same direction.