Southeast Asia Today

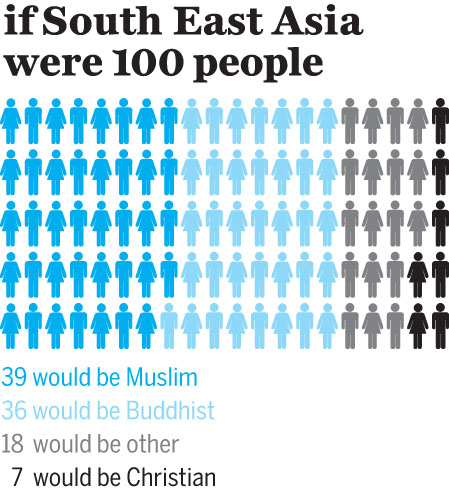

Southeast Asia in the 21st century is a dynamic region with a strong sense of possibility as millions move into the middle class. It is also a flashpoint for many pressing global issues: urbanisation, human rights, religious extremism and environmental degradation. For each country it is a careful balancing act, between growth and sustainability, autocracy and autonomy, self-determination and the strings attached to foreign investments. Increasingly, countries are working together, under the umbrella of ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations).

Best in Print

The Quiet American (Graham Greene; 1955) Classic portrayal of Saigon as the US slowly descends into war in Vietnam.

The Beach (Alex Garland; 1998) Now-legendary tale about a backpacker utopia in southern Thailand.

Smaller and Smaller Circles (F H Bataclan; 2016) Nuanced crime novel set in the gritty slums of Manila.

Married to the Demon King (Sri Daoruang; 2005) The ancient Hindu epic, the Ramayana, set in modern Bangkok.

Burmese Days (George Orwell; 1934) Account of close-minded colonials living in Myanmar.

Best on Film

Ilo Ilo (2013) Moving meditation on middle-class family life in Singapore, with an international cast.

First They Killed My Father (2017) Haunting adaption of Loung Ung’s personal account of life under the Khmer Rouge.

Cemetery of Splendour (2015) The living world and the spirit world collide in northern Thailand when soldiers succumb to a weird sleeping illness.

Apocalypse Now (1979) Set in Vietnam, filmed in the Philippines, this psychological thriller is the ultimate anti-war film.

Myanmar Falters

After decades of international-pariah status things were looking up for Myanmar. A landmark election in 2015 resulted in a sweeping victory for the National League for Democracy (NLD), the party of pro-democracy activist Aung San Suu Kyi. Foreign investment was flowing in; between 2010 and 2015 international arrivals rose by 490%.

In 2017, however, skirmishes between the military and the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) escalated into a full-blown humanitarian crisis. The Rohingya, who are Muslim, are one of Myanmar’s largest ethnic minorities, with an estimated population of 1 million. The official government view is that they are illegal immigrants from Bangladesh – both countries were common territories under the British crown – and that ARSA is a terrorist organisation. Denied citizenship, the Rohingya are a stateless people, without access to healthcare or education.

Following a deadly ARSA attack on a police station, the military launched a crackdown that, according to human rights groups, targeted civilians and rebels with equal ferocity. Villages burned and hundreds of thousands of Rohingya refugees fled to Bangladesh. Under Myanmar’s constitution, written by the military junta that ruled the country for decades, the commander-in-chief has full autonomy; still, de facto political leader and Nobel-laureate Aung San Suu Kyi has come under criticism for equivocating on the issue of the violence.

China’s Shadow

The 2016 election of American president Donald Trump saw the global superpower pivot abruptly inward – causing many in Southeast Asia to wonder if an increasingly assertive China would succeed in supplanting American hegemony in the region with its own. Under its ambitious One Belt One Road scheme, which seeks to revive the old overland and maritime Silk Road trade routes, China is already spearheading numerous infrastructure projects across the whole of Asia. Proponents say the project will promote growth; critics, notably India, have called it neocolonialism in disguise.

China has also been a bullish presence in the South China Sea (the East Sea, to Vietnam), fortifying its claims to disputed uninhabited territories – the Paracel Islands, the Spratly Islands and the Scarborough Shoal – with land reclamation projects and military outposts. What’s at stake is not only control of a strategic shipping lane but also fishing rights and potentially lucrative underground stores of natural gas. The Philippines took its claims against China to a UN tribunal and, in 2016, won, but has since backed down. Which raises the question: can countries in Southeast Asia afford not to do business with China?

Optimism & the Middle Class

Global market research firm Nielsen estimated that in 2015, 150 million Southeast Asians, or 25% of the population, could be classified as middle class. It expects that number to reach 400 million – more than half of the projected population – by 2020. While critics are quick to point out that upward mobility is patchy, hamstrung by corruption, cronyism and identity politics, in general, studies show consumer confidence is high – especially among millennials (and this in a region where the median age is 29). The new middle class wants to live in air-conditioned city apartments and have the latest mobile phones but is also keen to travel. And while many aspire to visit cities like Paris, most are in fact travelling within the region – getting to know their neighbours for the first time ever on such a large scale.

Damming the Mekong

The mighty Mekong River, which runs through China, Laos, Cambodia, Thailand and Vietnam, is seen as a huge potential source of hydropower. China has already built several dams on the Upper Mekong. Laos, down river, has already begun construction on two dams, Xayaburi and Don Sahong (near Si Phan Don, where the rare Irrawaddy dolphin lives). More are in the planning stages.

Hydropower is considered a source of clean energy, but comes with concerns. The Mekong supplies a quarter of the world’s fresh fish and has the world’s second-most diverse river ecosystem, after the Amazon; the Mekong Delta in Vietnam is among the world’s largest rice-growing regions. If the dams disrupt this, a crucial source of sustenance and livelihood for millions of people could be at risk.

POPULATION:

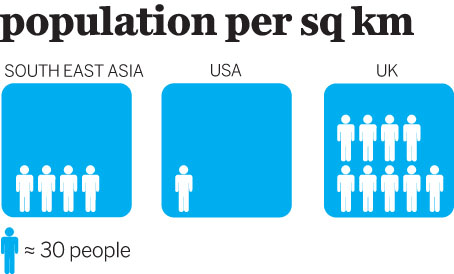

636 MILLION

GDP:

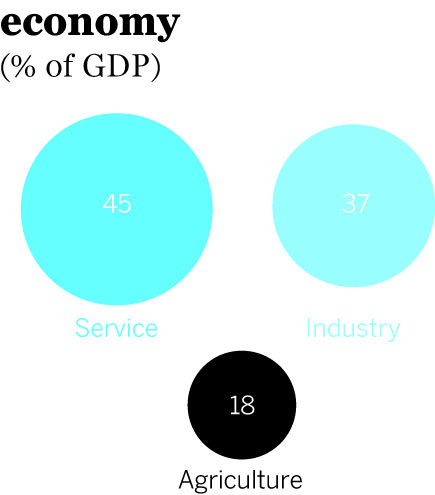

US$2.71 TRILLION

GDP PER CAPITA:

SINGAPORE US$52,961; CAMBODIA US$1270

INFLATION:

BRUNEI 0.4%; MYANMAR 8.5%

UNEMPLOYMENT:

CAMBODIA 0.5%; PHILIPPINES 5.6%