Being in the rainforest is like being in a giant green tunnel. Trees and plants grow so thick that you can’t even see the sky. The air is hot and humid. You’re covered in sweat. All of a sudden it starts pouring and the rain comes down so hard, it feels like someone turned a faucet on over your head. Just as suddenly the rain stops. And the noise! You hear strange buzzing, chirping, squeaking, ticking, and squawking sounds all around you. Welcome to Amazonia, the largest rainforest on Earth.

Amazonia is what people call the enormous, saucer-shaped area of tropical rainforest and grassy savannah that covers much of the northern part of South America. This area is also known as the Amazon rainforest, the Amazon River basin, or just the Amazon.

The Amazon River got its name from a Spanish explorer of Ecuador and Peru named Francisco de Orellana. In 1541, Orellana sailed down the entire length of a huge river to the open ocean. Along the way, he and his men were attacked by what he thought were women warriors holding enormous weapons. Orellana fought back and escaped. When he reached safety, Orellana named the river after the Amazons, a race of women warriors from Greek mythology.

Amazonia covers about 3.1 million square miles (about 8 million square kilometers). If you could pick it up and move it northward, it would almost cover the entire United States! Amazonia touches nine different countries, but more than half of it—60 percent, in fact—is in the country of Brazil. So why is this huge area called Amazonia and not Braziliana? Because of the incredible waterway that makes this enormous rainforest possible—the Amazon River.

The Amazon River is big. How big? Here are some facts about the Amazon River that are pretty amazing:

That’s not too bad for a river that starts as a five-inch stream in the Andes Mountains. The Amazon’s source is a trickle of water flowing off the side of Mt. Mismi, an 18,363-foot-high (5,597-meter) mountain in southern Peru. That trickle flows into a slightly bigger stream, and then another. Those streams turn into rivers, which wind their way across the continent of South America. They are full of water from melting snow pack in the mountains and lots and lots of rain. From the western edges of Peru to the eastern edge of Brazil, more than 1,000 of these rivers and streams meet and grow and head down into the saucer of the Amazon River basin, until finally the Rio Solimões flowing west meets the Rio Negro flowing south, and they turn into the Rio Amazonas, the Amazon River.

WORDS TO KNOW

humid: a high level of moisture in the air.

tropical: a hot climate, usually near the equator.

Amazons: a nation of fierce, women warriors in Greek mythology.

tributary: a river or stream that flows into a larger lake or river.

silt: soil made up of fine bits of rock. This soil is often left on land when floods recede.

Andes Mountains: one of the longest and highest mountain ranges in the world. The Andes run 4,500 miles (7,242 kilometers) along the west coast of South America.

There used to be two big arguments about the Amazon River. One was about where the river began. Another was about how long it was.

Scientists knew that the Amazon River started somewhere in the mountains of Peru, but where exactly? The definition of a river’s source is the point that is the farthest away from the river’s mouth. It also has to have water flowing into the river all year round. Finally, in 2000, scientists from five different countries on a National Geographic Society expedition traced the river’s source to Mt. Mismi.

This discovery helped settle the other big argument—about the river’s length. For many years, people argued about which river was longer: the Nile River in Egypt or the Amazon. The Nile measures 4,160 miles (6,695 kilometers) long while the Amazon was thought to be 4,020 miles (6,470 kilometers) long. But in 2006 when scientists measured the entire Amazon from its source on Mt. Mismi, they added 200 miles (322 kilometers) to its length. Now the Amazon is officially 4,250 miles long—64 miles (104 kilometers) longer than the Nile!

—FASCINATING FACT—

No bridges cross the Amazon River at any point.

Most people take a boat down the Amazon River, but on April 7, 2007, Martin Strel did something no one has ever done before: he swam 3,272 miles (5,268 kilometers) down the Amazon River. He did it in only 66 days!

Martin swam from Atalaya, Peru, to Belem, Brazil. He swam about 50 miles (80 kilometers) a day in all kinds of weather. Even when he was feeling sick. People worried that he would be attacked by sharks or piranhas, but his biggest problem was sunburn! Within two days of starting, his face and forehead were so sunburned that Martin had to wear a special mask. With this swim down the Amazon River, Martin broke his own Guinness Book World Record for long-distance swimming.

There’s one thing no one argues about. It’s that the Amazon River supports the largest and most diverse tropical rainforest on the planet. Amazonia is home to so many different kinds of plants and animals that scientists can’t count them all. Many species haven’t even been discovered or named yet. Almost a third of all the world’s living species of plants and animals live in Amazonia. Many of them live nowhere else on Earth.

How did this rainforest get so big and so diverse? There are two main reasons. The first is geography.

Millions of years ago, South America was part of a super continent called Gondwanaland. Gondwanaland also included Africa, Antarctica, and Australia. When Gondwanaland broke up, South America drifted on its own as a giant island. Many plants and animals that died out elsewhere—like sloths and anteaters—survived in South America.

WORDS TO KNOW

diverse: lots of different species.

species: a group of plants or animals that are closely related and look the same.

habitat: an area where a species or groups of different animals and plants live.

ice ages: periods in time when the earth cools down and ice spreads over a large part of the planet

Then a few million years ago, North and South America joined together. Plants and animals began moving back and forth between the two continents, making Amazonia even more diverse. For example, big cats like the jaguar originally lived only in North America. Over time, they moved south. Today, South America is the main habitat of the jaguar.

The other reason why Amazonia is so big and diverse is because much of its climate has remained pretty much the same for a very, very long time. In other parts of the world, ice ages wiped out many species. But parts of the Amazon’s rainforest stayed the same—hot, humid, and rainy for millions of years. Other parts of the rainforest changed a lot. The pockets of rainforest with a steady climate helped the old species of plants and animals thrive for millions of years, while the changing climate of other parts of Amazonia introduced lots of new species.

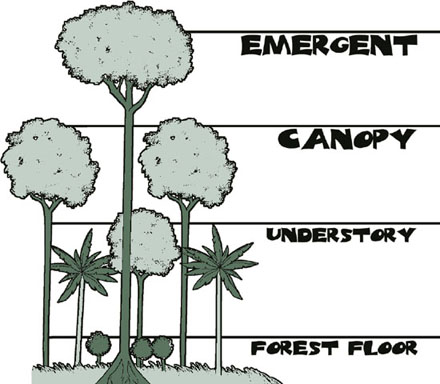

The Amazon rainforest has four layers: the emergent layer, canopy layer, understory layer, and the forest floor. Each layer is its own little microhabitat. Many plants and animals can only be found in one particular layer. Here is what each layer is like:

Emergent layer: This is where the tallest trees pop out, or emerge, above the rest of the rainforest. Some of these trees are more than 200 feet (61 meters) tall and their trunks can be as big as 16 feet (5 meters) around.

Trees in the emergent layer get plenty of sunlight, but they also are exposed to more wind and lots of rain. Plants that grow at the top of the emergent layer are usually small air plants called epiphytes. They get their nutrition from air, rain, and floating dust. Lots of birds, bats, insects, butterflies, and even monkeys live in the emergent layer. These creatures are safe up here, far above the predators below.

Canopy layer: Just below the emergent layer, the canopy layer creates a roof 60 to 90 feet (18 to 27 meters) above the ground. The canopy blocks out a lot of light from the forest floor, but it also prevents the soil from washing away when it rains.

Almost 90 percent of the animal species that live in the rainforest live in the canopy layer, including most bird species. There are also lots of monkeys, sloths, snakes, frogs, insects, lizards, and other animals living here. Many of these creatures never touch the forest floor.

The canopy layer is where most of the food of the rainforest grows, such as nuts and fruits. Vines called lianas grow here. These twine their way up the trees and tangle themselves in the top branches. There are also lots of bromeliads, orchids, and epiphytes in the canopy. These provide homes and food to lots of small creatures.

Understory layer: This is the layer of the rainforest between the canopy and the forest floor. There’s not much light here. Plants in this layer are usually less than 12 feet tall. The understory layer is home to most of the land animals of the rainforest, such as jaguars, anteaters, frogs, and snakes. It’s also home to millions of insects.

Forest floor: The forest floor is dark and damp. Almost no sunlight reaches the forest floor, so things decay really quickly. Very few plants grow here. The forest floor is where you’ll find fungus, lichen, and moss. You’ll also find creatures that help the decaying process, like worms, millipedes, and ants.

—FASCINATING FACT—

There are more than 1,500 different bird species in the Amazon rainforest. Many of them can only be found in certain types of trees in small areas of the rainforest.

Scientists need to study the canopy layer because that’s where most of the plants and animals live. But it’s not so easy when your laboratory is 90 feet (27 meters) in the air.

Over the years, scientists have tried lots of different ways to study the canopy layer. Some shot long ropes up into the trees. Some climbed up using mountain-climbing gear (this worked well but was dangerous). One scientist even tried to train a monkey to bring back samples of plants growing in the canopy.

Today, scientists use construction cranes, canopy walkways, ultralight gliders, and even balloons to observe the canopy. But we still don’t know very much about what happens in the rainforest canopy, or even how many plants and animals live there.

—FASCINATING FACT—

Scientists have discovered a species of ant living in the Amazon that has existed for 120 million years!

microhabitat: a very small, specialized habitat. This can even be a clump of grass or a space between rocks.

epiphytes: plants that grow on other plants. They get their food and water from the air and rain.

lianas: long, woody vines found in the Amazon and other areas of the world as well. bromeliads: a tropical plant family that includes the pineapple.

orchids: rare and beautiful flowers.

decay: the process of rotting or deteriorating.

fungus: a plant-like organism without leaves or flowers that grows on other plants or decaying material. Examples are mold, mildew, and mushrooms.

lichen: a plant-like organism made of algae and fungus that grows on solid surfaces such as rocks or trees.

You might not see other people when you walk though the rainforest, but it’s possible that other people can see you!

These people are Native Amazonians. They’ve lived here for thousands of years, mostly along the rivers. Most tribes have at least some contact with the outside world, but some tribes are completely isolated. They live by themselves in the rainforest, hunting, farming, and fishing, exactly the way their ancestors did thousands of years ago. The National Indian Foundation (FUNAI) is an organization set up to protect the rights of Native Amazonians. This group believes that there are more than 50 tribes that have absolutely no contact with the outside world.

Why do these tribes want to be left alone? Think about it: Before the first Europeans came to the Amazon in 1492, there were almost 6 million Native Amazonians in Brazil alone. Then the Europeans came and treated them terribly. They used the Amazonians as slaves, murdered them, and infected them with diseases that killed millions.

By the 1950s, only 100,000 Native Amazonians were left. To protect them, Brazil created places in the rainforest that were off limits to outsiders. The Native Amazonians live in peace there. Today, the population of Native Amazonians has grown to about 350,000 people. Most of them live in Brazil.

But even now, people illegally go onto native lands to hunt animals, search for gold, and steal oil and wood. The results can sometimes be deadly—usually for the native people.

—FASCINATING FACT—

The Amazon used to flow in the opposite direction that it does today. Millions of years ago, the Amazon flowed from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean—east to west. When the Andes Mountains formed on the west side of the continent, the river was cut off from the Pacific and began flowing from west to east.

hundred years ago, the only source of rubber in the world was found in Brazil, where rubber trees grow wild. If you cut into a rubber tree’s bark, a liquid called latex oozes out. People collected the latex in buckets and then shipped it all over the world to be made into rubber.

Growing industries were desperate for more rubber. They couldn’t get enough. This set off a rubber boom in Brazil. People raced to Brazil and stole land that belonged to the Amazonians. They enslaved the natives, killing them if they didn’t produce enough latex, or if they tried to escape. Millions of Native Amazonians died during the rubber boom.