Altruism in Everyday Life

IN 2006, three years after starting EvoS and a year before the start of the Evolution Institute, I began using my hometown of Binghamton, New York, as a field site for studying people in the context of their everyday lives. Field studies are the backbone of evolutionary research because species must be studied in relation to the environmental forces that shaped their properties. What would we know about chimpanzees without the kind of field research that Jane Goodall made famous? What would we know about Darwin’s finches if we didn’t study them in the Galapagos Islands?

Most research on human behavior is not like this. The bulk of psychological research is conducted on college students without any reference to their everyday lives. Sociologists and cultural anthropologists conduct field research but seldom from an evolutionary perspective. Then there are dozens of research communities with the practical objective of solving a particular social problem, such as addiction, child abuse, or risky adolescent behavior. This kind of applied research often takes place outside the laboratory, but the research communities tend to be isolated from each other and from the so-called basic scientific disciplines, including evolutionary science.

The idea of studying people from all walks of life as they go about their daily lives from a unified theoretical perspective therefore turned out to be surprisingly novel.1 EvoS and the Evolution Institute enabled me to expand the approach beyond my own efforts. We call the Binghamton Neighborhood Project a “whole university / whole city” approach to community-based research and action. The “whole university” part is the network of faculty and students organized by EvoS, who speak a common theoretical language in addition to their disciplinary training. The “whole city” part is all sectors of the city—the neighborhoods and their residents; the government; the schools; the health, safety, and social service agencies; and the many other organizations that exist in any city to improve the quality of life. The Evolution Institute has organized workshops on topics such as education, risky adolescent behavior, and quality of life that can be used to implement new policies and practices at any location.2

This synthesis enables the study of altruism in the context of everyday life. The Darwinian contest between altruistic and selfish social strategies, defined at the level of action, is taking place all around us. It results not only in genetic and cultural change over the long term but also in the capacities that we develop during the course of our lifetimes and the choices we make on a moment-by-moment basis. Seeing the Darwinian contest clearly can help us create social environments that favor altruism as the winning social strategy, improving the quality of life in anyone’s hometown.

Our first project in Binghamton involved, with the help of the Binghamton City School District, giving a survey called the Developmental Assets Profile (DAP) to public school students in grades 6–12. The DAP was developed by a nonprofit organization called Search Institute that has been dedicated to promoting healthy youth development for more than fifty-years.3 The profile measures properties of individuals that contribute to their healthy development (internal assets) and social support from various sources such as family, neighborhood, school, religion, and extracurricular activities (external assets). Among the internal assets are attitudes toward others and society as a whole, measured by statements such as “I think it is important to help other people,” “I am sensitive to the needs of others,” and “I am trying to make my community a better place.” Students indicated their agreement with these statements on a scale from 1 (low) to 5 (high), which we summed to calculate a score that we called PROSOCIAL. The term prosocial refers to any attitude, behavior, or institution oriented toward the welfare of others or society as a whole. The term is agnostic about the amount of sacrifice required to help others or to psychological motivation. Thus, it is largely synonymous with what I have been calling altruism as defined in terms of action in this book.

Unsurprisingly, the distribution of PROSOCIAL scores took the form of a bell-shaped curve. Most students indicated moderate agreement with the items. A few whom we dubbed High-PROs appeared to be budding Mother Teresas by indicating strong agreement, and a few that we dubbed Low-PROs appeared to be budding sociopaths by indicating strong disagreement.

So far we had not done anything special. Hundreds of schools and communities use the DAP to measure the developmental assets of their youth. In addition, the PROSOCIAL score doesn’t necessarily measure altruism at the level of either actions or thoughts and feelings. Perhaps the High-PROs were just trying to make themselves look good. More work would be required to show that High-PROs walk the walk in addition to talking the talk.

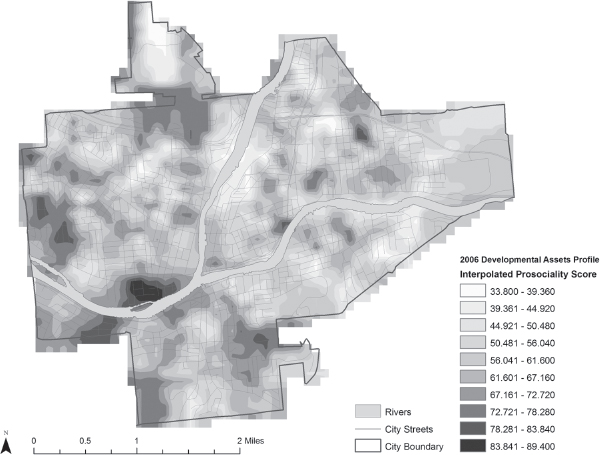

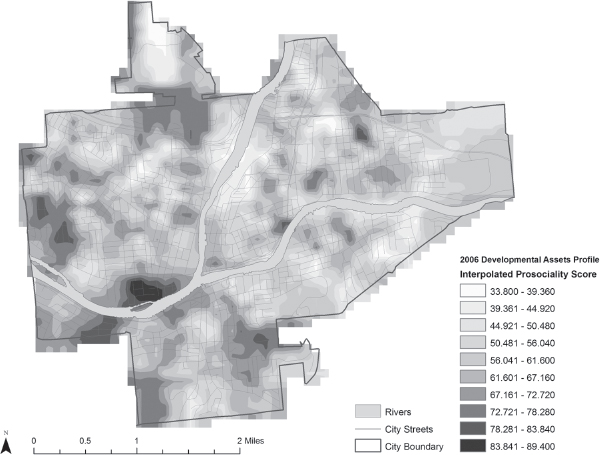

The next thing we did was more novel. By linking the PROSOCIAL scores of the students with their residential addresses, we created a map of the city of Binghamton (see Figure 8.1).4 For those unfamiliar with Binghamton, it is located at the confluence of two rivers, the Susquehanna and Chenango, and the downtown area is between the two arms of the Y. The residential addresses of the students would look like a scatter of points on the map. These points were converted to a continuous surface by a method known as kriging, which calculates an extrapolated PROSOCIAL score for each location on the map by taking an average of the actual PROSOCIAL scores for the students closest to the location. The dark regions represent neighborhoods in which most of the students report being highly prosocial. The light regions represent neighborhoods in which most of the students could care less. The spread among neighborhoods was a whopping 50 points on a 0–100 scale!

This map had a powerful effect upon me. Remember that I am trained as a biologist and I am accustomed to seeing maps like this that show the distribution and abundance of nonhuman species. Suppose that the map shown here was for a native plant species that we wanted to preserve. Our job as conservation biologists would be to identify the environmental conditions that cause the species to be common in some areas and absent in others. Perhaps it is soil nutrients, a competing plant species, or herbivores. Once we identify the salient conditions, we can try to provide them more widely, thereby expanding the plant’s niche. If we succeed, then the map will grow darker and darker with each census.

The power of the map is to suggest that a human social strategy such as prosociality could be conceptualized in the same way. Most people are behaviorally flexible and can calibrate their prosociality to their circumstances.5 The map suggested that the expression of prosociality in the city of Binghamton was spatially heterogeneous. If the underlying environmental factors could be identified, then the niche for prosociality could be expanded in the same way as the niche for a plant species. If we administered the DAP to the students every year, then we could track our success or failure by watching the dark areas expand or contract.

FIGURE 8.1 A MAP OF PROSOCIALITY FOR THE CITY OF BINGHAMTON, NEW YORK

The school superintendent and teachers who helped administer the DAP shared my excitement about the map and what it represented. They had more practical experience with the students than I ever would, and some of them were born and raised in the Binghamton area. Even for them, the map seemed to show something new and to offer the promise that visualizing the distribution and abundance of prosociality might be the starting point for expanding its niche.

What factors are likely to influence the expression of prosociality in behaviorally flexible individuals? Roughly, they are the same as the factors that favor prosociality as a product of genetic and cultural evolution. High-PROs can expect to succeed when they are in the company of other High-PROs. Otherwise they can expect their communitarian efforts to be exploited and wasted. The other assets measured by the DAP enabled us to test this hypothesis. Bearing in mind that not all social interactions take place within neighborhoods, we correlated the PROSOCIAL score of each individual student with the amount of social support they reported receiving from their family, neighborhood, church, school, and extracurricular activities. The result was a correlation between the prosociality of the individual and the overall prosociality of the individual’s social environment with a coefficient of 0.7 (on a scale from –1 to 1). In plain English, those who reported giving also reported receiving, which is the basic requirement for altruism defined in terms of actions to succeed in a Darwinian world. The results could have been otherwise. The amount of social support that individuals reported receiving could have been uncorrelated or negatively correlated with their own PROSOCIAL score, but this was not the case.

The size of the correlation coefficient is remarkable against the background of evolutionary theories of social behavior. Much has been made of the genetic similarity between relatives as the foundation for the evolution of altruism. The expression of altruism is expected to be proportional to the correlation coefficient for shared genes, which is 1 for identical twins, 0.5 for full siblings, and so on down to 0 for individuals who are genetically unrelated. An important event in the history of inclusive fitness theory was the realization that the correlation between donors and recipients of altruism can be based on factors other than genealogical relatedness, as I recounted in chapter 4. The kind of behavioral sorting that takes place among water striders described in chapter 3 provides an example in nonhuman species. A correlation coefficient of 0.7 suggests that mechanisms causing those who give to also receive in the city of Binghamton are so strong that they exceed the correlation among full siblings in a simple genetic model.

A lot of work was required to confirm that the map based on the PROSOCIAL scores actually represented differences among neighborhoods in prosociality.6 In one study, we employed a method from social psychology that involved dropping stamped addressed envelopes on the sidewalks all over the city to see who was kind enough to put them in the mailbox. In a second study, we employed a method from behavioral economics that involved students choosing between cooperative and noncooperative strategies in a game played for money. In a third study, we measured naturalistic expressions of prosociality such as holiday displays during Halloween and Christmas. In a fourth study, we conducted door-to-door surveys of adult residents. All of the studies broadly supported each other and revealed important new findings. For example, it turns out that the richest kids in Binghamton are not necessarily the most prosocial. Having money means that you don’t need to cooperate very much with others to get what you want. In sociological parlance, financial capital and social capital substitute for each other to a certain extent.7 The most prosocial kids in Binghamton don’t have much money but have lots of practice cooperating with each other to get things done. The least prosocial kids in Binghamton have neither financial nor social capital. They have become lone wolves.

Once we were convinced that our map reflected real differences in prosociality, we began to focus on other questions: What are the mechanisms of behavioral flexibility? Can individuals calibrate their degree of prosociality to their social environments throughout their lives? Or do they lose their flexibility as they grow older? There is no single answer. A lot is known about mechanisms of behavioral flexibility in humans and other species. Early childhood experiences can have lifelong consequences.8 The influence of the environment can take place before birth and even previous generations.9 The burgeoning field of epigenetics shows that environmental effects can alter the expression of genes in ways that are transmitted across generations.10 Your propensity to be prosocial is conceivably the result of the experiences of your parents, grandparents, and even more distant ancestors. In addition to environmental effects, genetic polymorphisms cause humans and other species to respond to their environments in different ways. Some individuals are like hardy dandelions that can grow under a wide range of conditions. Others are like orchids that wilt under harsh conditions but grow into objects of rare beauty under optimal conditions.11

These genetic and long-lasting environmental effects notwithstanding, many nonhuman organisms retain an impressive ability to respond to their immediate environments. A snail quickly withdraws into its shell when it senses danger and emerges just as quickly when danger passes. Our research suggests that people have a snail-like ability to change their behavior in response to the prosociality of their social environment, regardless of their past experiences.

In one study headed by Daniel T. O’Brien, who was my graduate student at the time and is now doing similar work in Boston, we asked Binghamton University college students (most of whom were unfamiliar with the city) to rate the quality of neighborhoods based on photographs. Their rating correlated quite highly with what the Binghamton public schools students who actually lived in the neighborhoods indicated on the DAP. In a second study, Binghamton University students viewed photographs of the neighborhoods and then played an experimental economics game with public school students from the neighborhoods. This was not an imaginary game but was played for real money. The players did not physically interact, but the college student’s decision whether to cooperate in the game was paired with the decision of a public school student from the neighborhood, based on our previous study with the public school students. The college student’s willingness to cooperate was strongly correlated with the quality of the neighborhood assessed from the photograph. Just like snails, it appears that we assess our surroundings and withdraw into our shells when we sense danger. In our case, this means not only protecting ourselves from physical harm but also withholding our prosociality. We can transform from a High-PRO to a Low-PRO in the blink of an eye.12

A natural experiment that took place in Binghamton enabled us to measure behavioral flexibility another way.13 Three years after we created the first map, we again administered the DAP. Hundreds of students took the DAP both times, so we could measure changes in their prosociality and other developmental assets over the three-year period. Of these, some had moved their residential location within the city of Binghamton. Their new neighborhood might be better or worse than their old one. Statistically, we were able to test whether the change in their social environment rubbed off on their own prosociality. It did. The students became more or less prosocial depending upon the quality of their new neighborhood. They remained behaviorally flexible, regardless of whatever genetic and long-lasting environmental effects might also be operating.

Natural experiments such as this one are suggestive but seldom definitive. In 2010 we had an opportunity to conduct a more rigorous test when the Binghamton City School District asked us to help them design a new program for at-risk high school students called the Regents Academy. They realized that students who were failing most of their courses in the eighth and ninth grades would almost certainly drop out unless something was done. The school district was willing to create a school within a school, complete with its own principal and staff, to solve the problem. Could we help them design the program?

I leaped at this opportunity, just as I leaped at the opportunity to create the Evolution Institute. One of my graduate students, Richard A. Kauffman, had been a public school teacher before returning to school and joined me on the project. I was also working with Elinor Ostrom, whom I had met as part of my economic work described in the previous chapter. With her postdoctoral associate Michael Cox, we were placing the design principles that she derived for common-pool resource groups on a more general theoretical foundation.14 The design principles provide a highly favorable social environment for the expression of prosociality. They ensure that efforts on behalf of others and the group as a whole will be well-coordinated (design principles 1 and 3), won’t be exploited from within (design principles 2–6), and will be free from external interference (design principles 7–8). (See chapter 1 for more on the design principles.) As such, they provide a blueprint for almost any group whose members must work together to achieve a common goal.

We therefore designed the Regents Academy to embody the eight core design principles. Students, teachers, and staff should have a strong group identity and understanding of purpose. The distribution of work should be equitable, and people should be credited for their contributions. Students should be involved in decisionmaking as much as possible. Good behavior should be monitored, and corrections should be gentle and friendly, escalating only when necessary. Conflict resolution must be fast and regarded as fair by everyone involved. The school must be allowed to create its own social environment as much as possible and to draw upon other groups in constructive ways. In addition to “Ostrom’s 8,” as we affectionately called them, we added two additional design principles that we thought were especially important in an educational context. The ninth was to create an atmosphere of safety and security, since fear is not an atmosphere conducive to long-term learning. The tenth was to make long-term learning objectives also rewarding over the short term. Research shows that even gifted students succeed primarily when they enjoy developing their talents on a day-to-day basis.15 Nobody learns when all the costs are in the present and all the benefits are in the far future.

These design principles make perfect sense when they are listed, but how many groups actually employ them? Ostrom found that common-pool resource groups vary in their employment of the design principles, which is how she was able to derive them in the first place. The same variation exists for other kinds of groups. As we were designing the Regents Academy, we were reading the educational literature and encountering some school programs that worked very well. Unsurprisingly (to us), they tended to employ the design principles. But the fact that these programs worked well did not mean that they had become common educational practice. On the contrary, education in America (and many other countries) appears to be driven by forces that cause massive violations of the design principles. That was definitely the case for at-risk students in the city of Binghamton. Their experience at the Regents Academy would be very different from their experience at Binghamton’s single high school.

To select students to enter the Regents Academy, we compiled a list of all eighth and ninth graders who had failed three or more of their basic subjects during the previous year. Then we randomly selected students from this group to invite to join the Regents Academy. The others formed a comparison group that we tracked as they continued their normal education. Almost all of the families contacted agreed to have their children join the Regents Academy, so we succeeded at creating a randomized control trial, which is the gold standard for studies of this sort. We would know with a high degree of confidence whether the Regents Academy succeeded or failed.

What happened? Within the first marking quarter, the Regents Academy students were performing much better than the comparison group, and the difference was maintained for the rest of the year. The most stringent comparison came at the end of the year when all students took the same state-mandated exams. Not only did the Regents Academy students greatly outperform the comparison group, but they actually performed on a par with the average high school student in the city of Binghamton.16

The Regents Academy also improved the developmental assets of the students, as measured by the DAP.17 Regents Academy students felt better about themselves and reported experiencing more family support than the comparison group. They liked school even better than the average Binghamton high school student, suggesting that all students can benefit from the design principles approach, not just at-risk students. Their PROSOCIAL scores went up, although not enough to be statistically significant. The benefits were achieved to an equal degree by all gender, ethnic, and racial categories. Everyone thrives in a social environment that causes prosociality to win the Darwinian contest.

I have based this chapter primarily on my own experience studying prosociality (= altruism defined at the level of action) in the context of everyday life in my hometown of Binghamton. In addition, through the Evolution Institute I have become familiar with many other programs that employ the same principles and achieve similarly impressive results—not just for education, but for nearly all aspects of everyday life, such as mental health, parenting practices, and the design of thriving neighborhoods. As one example, a way of organizing elementary school classroom activities called the good behavior game exemplifies the design principles and has lifelong positive effects that have been demonstrated in randomized control trials.18 A program that teaches good parenting skills called Triple P (for Positive Parenting Program) originated in Australia and is being implemented worldwide. In one randomized control trial, Triple P was implemented in nine South Carolina counties randomly selected from eighteen counties sharing similar characteristics. Triple P improved parenting practices at a population-wide scale, as measured by public health statistics such as foster care placements and hospital emergency room visits by children. The estimated cost of implementing Triple P in a county was eleven dollars per child, which is trivial compared to the societal benefits, including cost savings by the many social services that must deal with the fallout of bad parenting practices.19

Every time I encounter one of these programs, I am amazed at its success in improving human welfare and the quality of the science validating the results, yet I am equally amazed that they aren’t more widely known and implemented. Paradoxically, the world is full of programs that work but don’t spread. One reason is that they emanate from so many isolated research communities that lack a common theoretical framework.

To address this problem I teamed up with three leading researchers from the applied behavioral sciences, Steven C. Hayes, Anthony Biglan, and Dennis Embry, to write an article titled “Evolving the Future: Toward a Science of Intentional Change.”20 The article has two main objectives: to sketch a basic science of intentional change rooted in evolutionary theory and to review outstanding examples of positive intentional change that are well validated but little known outside their disciplinary boundaries. As we state in our article, we are closer to a science of intentional change than one might think.

Readers should consult the article for a closer look at how to improve the quality of everyday life. I conclude this chapter by making a few points that are most relevant to the topic of altruism. We sometimes need to remind ourselves how much human social life requires prosociality—people acting on behalf of other people and their groups as a whole. The need for prosociality begins before birth and continues throughout development. Most of our personal attributes that we regard as individual because they can be measured in individuals are the result of developmental processes that are highly social. Prosociality during development is a master variable. Having it results in multiple assets. Being deprived of it results in multiple liabilities. This point is often obscured by the fact that every problem experienced by young people tends to be studied in isolation and without a unifying theoretical framework.

After we become adults, almost all of our activities require coordinating our activities and performing services for each other. Some of these activities take place without requiring our attention, as if guided by an invisible hand, but only if there has been a past history of selection favoring self-organizing processes at the appropriate scale, as we saw in the last chapter. At the local scale—in our families, neighborhoods, churches, and businesses—prosocial activities are up to us. If we don’t do them, they don’t get done and the quality of life declines.

Behaving prosocially does not necessarily require having the welfare of others in mind, as we have seen in previous chapters. Theoretically, Low-PROs could contribute as much to society as High-PROs. A proponent of Ayn Rand might even expect Low-PROs to contribute more to society than well-meaning but counterproductive High-PROs. The results of our research tell a different story. People who agree with statements such as “I think it is important to help other people” actually do help other people and work toward common goals more than people who express indifference toward helping other people. For the most part, no invisible hand exists to convert the mentality of Low-PROs into prosocial activities.

Of course, someone who scores high on the PROSOCIALITY scale does not necessarily qualify as an altruist, defined in terms of thoughts and feelings. All sorts of selfish motivations can result in a desire to help others. But obsessing about the motives of High-PROs is like obsessing about whether to be paid by cash or check. In my experience, people engaged in prosocial activities tend to care about motives only insofar as they bear upon commitment to the task. As long as you are a solid member of the team, you can think about it however you like. The many-to-one relationship between proximate and ultimate causation helps to explain why this pragmatic attitude makes sense.21

High-PROs might be essential for volunteer organizations, neighborhood associations, and churches, but how about businesses? There is a widespread impression that businesses are and must be driven by selfish financial motives, but an important book titled Give and Take22 by Adam Grant, who is a professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton Business School, shows otherwise. Grant distinguishes between three broad social strategies. Givers (= High-PROs) freely offer their services without expectation of return. Reciprocators make sure that their services are repaid. Takers (= Low-PROs) try to get as much as they can and give as little as possible in return. It might seem that givers are quickly eliminated in the hardball world of business, leaving only reciprocators and takers, but this is an illusion. Grant reviews an impressive body of evidence showing that givers are highly successful in the business world, as long as they surround themselves with other givers and avoid the depredations of takers. In other words, the business world is no different than any other enterprise requiring prosocial activities.

Why should this be so surprising? How did the impression that businesses must be driven by greed get established in the first place? Most business schools wholeheartedly adopted the Homo economicus version of economics described in the previous chapter as their worldview. Homo economicus is driven entirely by greed, so that’s how we’ve all been trained to believe regarding the business world. During a video interview that I conducted with Grant, he said that Wharton School students frequently tell him how much they want to help others and society as a whole—which they plan to do by first making a lot of money and then becoming philanthropists! It doesn’t occur to them that they can begin functioning as High-PROs right away.

Evolutionary theory and a large body of evidence reveals the importance of being directly motivated to help others and society as a whole—to be a High-PRO and not a Low-PRO. But becoming a High-PRO requires more than counseling and encouragement. It requires building social environments that cause prosociality to succeed in a Darwinian world. Provide such an environment, and people will become High-PROs without needing to be told.