![]()

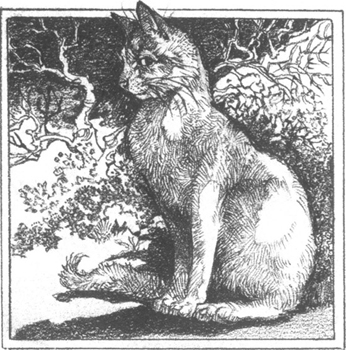

CHESTER TOOK A MOMENT to bathe his tail. Howie, Dawg, and I settled down on our bed of pine needles and leaves and waited. The air that ruffled our hairs and rustled the trees above us was changing, perhaps in anticipation as well, though anticipation of what, I couldn’t say. When Chester was ready to begin, he assumed the classic cat position—head high, spine erect, front legs as straight and formal as marble columns—and wrapped his freshly laundered tail around himself, leaving only the tip in motion. For a time, it flicked the ground. Then slowly it quieted. And the story began.

“Once upon a time in Transylvania,” Chester said, “high in the Carpathian Mountains in a little town called Kasha-Varnishkes, there lived twin brothers, whose names were Hans and Fritz. The simple sons of simple innkeepers, their lives were—”

“Free from care,” said Chester. “Free from worry. Until that fateful day when everything changed. ‘Wash up for dinner,’ their mother told them, as she did every night before the evening meal. ‘Going, Mummy,’ said Fritz, the more obedient of the two. ‘Take your brother with you,’ their mother said.”

“Well, sure,” Howie put in. “After all, you don’t want dirty Hans at dinner.”

Chester sighed deeply and continued. “They were just going outside to the well when they heard a crash. Rushing back in, they found their mother lying in a heap on the floor. ‘Mummy!’ Fritz cried.”

“This Fritz is a real wimp,” Dawg muttered. I tended to agree, though I said nothing.

“ ‘Is she dead?’ said Hans. ‘No,’ Fritz told his brother. ‘But I think she’s had a relapse. Oh, Hans, you know what we were told the last time this happened. There is only one doctor, a doctor in far-off London, who can cure her. What are we to do? We are the poor children of poor innkeepers. So few people pass by this way, it will take us years to save enough money to go to London and get help. And Mummy doesn’t have years.’ Fritz began to cry.

“Feeling her son’s teardrops on her lips, the woman blinked open her eyes. Is that you, Stefan?’ she said. Hans and Fritz looked sadly at each other. ‘Mummy, you know that Papa is gone,’ said Fritz. Then to his brother, he whispered, The disease has already affected her mind.’ Their mother smiled wistfully. ‘I remember now,’ she said. ‘He’s gone to wash for dinner.’

“Fritz manfully choked back his tears. ‘That’s right,’ he said. ‘Oh, Hans, yet we can hope. We must do everything in our power to help Papa save Mummy.’ ‘There’s only one way I know of,’ said Hans. He exchanged a knowing look with his brother, who nodded solemnly.

“And so it was that the next morning, Hans and Fritz secretly ripped out a corner of a page from the newspaper and set off in search of Diabolicus.”

“Dr. Emil Alphonse Diabolicus,” Chester went on to explain, “was the subject of talk and the object of fear in the town of Kasha-Varnishkes. He lived in an ancestral home, a decaying castle high upon a mountain bluff, and was never seen by day and only rarely by night. Some said he was a mad doctor, engaged in research, playing God. Others called him the devil’s apprentice. But no one knew for certain what went on in the castle on the bluff. His housekeeper, who came into town each week to buy food, didn’t engage in idle conversation. And none of the peasants were brave enough to venture up the mountainside to find out the truth for themselves. In fact, were it not for an unassuming little ad in the local paper, Hans and Fritz would never have known about the moneymaking opportunity they were about to pursue.

“Top bucks for research assistants,’ the ad read. Inquire at The House of Dr.E.A.D.’”

I shuddered. “The House of Dread?” I asked Chester.

“The house of Dr. Emil Alphonse Diabolicus,” he replied. “It was Hans whose hands lifted the heavy knocker on the door, for once there, Fritz was ready to turn back. ‘Courage,’ Hans said as the door creaked open. With the eyes of an eagle and the nose of a hawk, the housekeeper looked down at the boys.

“ ‘What do you want?’ she said.

“ ‘We . . . we’ve come about the ad,’ said Hans. There was a roll of thunder, even though it was a sunny day.

“ ‘Thank the powers-that-be!’ the old woman exclaimed, clutching her withered hands to her chest. ‘You’ve arrived just in time. Come in, lads, come in.’

“She put Hans and Fritz to work that very afternoon, and they continued to work each afternoon for the next two weeks. But in all that time they never met Dr. Diabolicus. They followed the instructions of the housekeeper, who called herself Erda, and were paid promptly at the end of each day when they delivered to her what it was they had been sent out to find.”

“What?” Dawg said. “What were they sent out to find?” I noticed that he seemed more wide awake than ever. I was beginning to wonder if Chester’s little story would put him to sleep by midnight. But I confess I almost didn’t care. I wanted to hear the rest of the tale myself.

“Yeah, Chester,” I said. “What were they looking for?”

A twinkle came into Chester’s eyes. “Rabbits,” he said.

“Rabbits!” Howie exclaimed. “What did he want rabbits for?”

“That was just what Hans and Fritz were asking themselves. It seemed that Dr. Diabolicus couldn’t get enough rabbits. The ad in the paper said “research assistants,”’ Hans pointed out one day. ‘So he must be using the bunnies for research. But what kind of research?’ ‘Oh,’ said Fritz, 1 don’t want to know. We’re getting paid, isn’t that enough? We’ll soon have the money to buy our passage to London, that’s all that matters.’

“But it wasn’t all that mattered to Hans. He had always been a more curious child than Fritz.

Two weeks of collecting rabbits for an unseen employer had proved more than he could take. He had to know what happened to the rabbits once they reached the House of Dr.E.A.D. Even more pressing was his desire to see the mysterious Dr. Diabolicus for himself.

“ ‘Perhaps,’ he said, trying to reason with his brother, ‘if we were to meet Diabolicus, we could convince him to let us help in other ways. Then, we’d not only have the money to get to London but to return home as well.’

“Well, it was hard for Fritz to argue with that kind of logic, especially since their mother’s illness was progressing rapidly. Just the night before, she had boiled a sheepskin coat and called it mutton stew. The guests had not been amused. The brothers agreed that that night, they would find a way to sneak into the castle and speak with Dr. Diabolicus directly.

“Little did they know that the citizens of Kasha-Varnishkes had plans of their own for that evening, plans that would forever alter the destinies of the Transylvanian twins.”

An owl hooted, eerily punctuating the pause in Chester’s narrative. The night had become still, the air heavy. “What happened next?” Howie said, his voice sandpapery with fatigue. “Did Hans and Fritz find out why Diabolicus wanted the rabbits?”

“Oh, they found out, all right,” said Chester. “Would that they hadn’t. But Hans could not contain his curiosity.”

“Sounds like someone I know,” I muttered, thinking of all the trouble Chester’s curiosity had gotten me into at one time or another.

Chester gave me a look but chose not to respond. “Late that afternoon, they delivered the day’s catch as usual,” he continued. “But instead of leaving immediately for home they asked Erda if they could each have a glass of milk. Before answering them, she glanced at the window. ‘Well, all right,’ she said. ‘But you’ll have to hurry. It’s almost dark.’ That’s okay,’ said Hans. ‘We know our way home.’ ‘That isn’t what worries me,’ said Erda, and she went off to the kitchen.

“The moment she had left the room, Hans and Fritz raced quickly up the winding staircase that led to the upper floors of the house. Fritz clutched his brother’s shirttail as they inched their way along the dark hall on the second level. Where are we going?’ Fritz asked nervously. There,’ said Hans, pointing to a pool of light spilling out from under a door at the far end of the hall. He hurried Fritz along, not wanting to be found out by the housekeeper.

“Despite its heaviness, the door opened easily and soundlessly on well-oiled hinges. The boys were not surprised by what they found inside. The candlelit laboratory was filled with buzzing machines, bubbling beakers, ticking clocks, and rabbits. Cages and cages and cages of rabbits.

“ ‘At least we know they’re alive,’ Hans said.

“ ‘Alive and yet not alive,’ said a voice as well-oiled as the door.

“It was then that the boys met Dr. Diabolicus. He stood in the doorway, his pale face a shroud of skin on ancient bones, his lips red with life like overripe berries. He wore a silk robe, black as night with a silver moon and star embroidered on the breast pocket. In his white hands he carried two glasses of milk. These are yours, I believe,’ he said, extending them toward the boys.

“Th-thank you, sir,’ said Hans, stepping forward. He tried not to show his fear, while Fritz was failing miserably behind him. ‘Won’t you join us?’

“ ‘I don’t drink . . . milk,’ said Diabolicus.

“Hans’ hands shook as he reached for the glass. ‘Don’t be frightened,’ Diabolicus said. ‘I’m not angry with you.’

“ ‘You’re not?’ said Fritz.

“ ‘Not at all. Without your help, I would have been unable to complete my experiments.’ His eyes gleamed as he looked about the room. ‘These rabbits are all evidence of my success,’ he said. They are, like me, alive—yet not alive.’ Hans and Fritz looked at each other, wondering what it was he meant by that phrase. ‘I have been so lonely, boys,’ said Diabolicus. ‘But now my lonely days are over!,’ Opening a cage, he removed a pair of rabbits, white with black markings on their backs. ‘Bella,’ he said. ‘And Boris. These are my special ones. They will accompany me through eternity and be my friends, my soulmates, always. You can understand how much pets mean to someone as lonely as I, can’t you, lads?’”

I don’t know about Howie and Dawg, but I got a little teary at that.

“ ‘Wherever I go,’ Diabolicus continued, ‘Bella and Boris shall go with me. And they will never die . . . never, never.’

“Hans started to ask how this could be, when the sound of pounding footsteps drove the thought from his mind. ‘Hurry,’ the housekeeper cried, as she broke into the room. ‘Hurry, master! They’re coming!’

“ ‘Get hold of yourself, woman! Who’s coming?’

“ ‘The peasants. They’re carrying torches. They’re crying, “The monster must be destroyed!” Oh, master, we must leave at once.’

“ ‘The fools,’ said Diabolicus. ‘Don’t they realize it is Saint George’s Eve, the one night of the year I can’t be destroyed?’

“ ‘But the rabbits,’ said the housekeeper. ‘You don’t know for certain about the rabbits. They could be destroyed. All your research, all your work... all for nothing!’