1

The Idea of Liberal Order

Hegemons are vain creatures. Having risen to power, they are easily afflicted with ‘middle kingdom’ syndrome, the fancy that they possess superior wisdom, standing at the centre of the cosmos with little to learn from others.1 Far from being an American peculiarity, selfcentric worldviews are an ancient conceit, from Persia’s King Darius I, Spain’s Philip II, China’s Ming dynasty, Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, to Napoleonic France. The assumption of their own specialness encourages hegemons to identify their interests with those of other states, to see success as the sign of the cosmos’s favour and adversity as a test of faith. In turn, this loosens restraint and makes them war-prone. They practise what medieval China called ‘barbarian management’, without suspecting themselves of being the source of belligerence. They give themselves permission to pick and choose among rules in ways they would not tolerate from others, to stand outside their system the better to sustain it.

When American power climaxed around the turn of this century, policymakers spoke as lords of the horizon. ‘We’re an empire now’, said a senior presidential advisor in 2002, ‘and when we act, we create our own reality.’2 The attitude that America could make the world anew, with triumphant finality, was on display on 1 May 2003 when President George W. Bush descended from a Viking jet onto the USS Abraham Lincoln to declare the end of major combat operations in Iraq. Bush spoke of free-market democracy as humanity’s destiny, of America’s divine appointment, reworking biblical quotations to substitute ‘America’ for ‘God’.3 Ensuing military and economic disasters failed to extinguish American leaders’ confidence in the meaning of history. Even President Obama, who positioned himself against imperial hubris, returned to the same waters. He declared that the ‘arc’ of the moral universe ‘bends towards justice’, presuming that history is directional and that he knew its destination.4

This is not to say that all hegemonies are equivalent, or identical, ‘black boxes’. They are not. A Chinese-dominated Asia would not simply replicate the American Century. Details would vary in important ways: the scale of brutality and repression, the willingness to intrude on other states’ internal way of life and constitutional systems, and the level of ambition to reach beyond their own region. A Chinese hegemony would probably be both more brutal yet less prescriptive domestically, except when demanding obedience. These details matter. For millions, those differences are worth fighting and dying for. They matter for those who are on the receiving end, and for those who exercise power. And they matter regarding the sustainability of the project. Some hegemonies overreach further and destroy themselves more quickly than others.

Rather, the claim here is that most hegemonies share an underlying set of characteristics: a sense of their own ‘specialness’ and singularity; a selective attitude to rules; a proneness to war; and an elevated sense of themselves as a source of order and light. Hypocrisy – organized or casual – tends to reign. With growing power, these characteristics tend to increase. Those who articulate liberal order resist this claim. They argue that American hegemony was different, not only in degree but in substance. It was not just a new order, they say, but a new kind of order. This time, order was not just another word for structure or empire, but something qualitatively different, an organization of power defined and redeemed by liberalism. In the tradition of Hedley Bull, it established a sense of common interests, rules prescribing behaviour, and institutions that make those rules effective. To say this, however, is to speak like a hegemon.

This is not an arcane debate. It is linked to fundamental questions about how our world should be. Panegyrics to the pre-Trump order are an intervention in present political struggles. They are fashioned in an hour of emergency, as their creators fear the night is falling. They are uttered in order to affirm a sense of American mission, to warn the superpower against the temptation to narrow its horizons or retreat or give up its role as moral tutor. As a theoretical and historical proposition, liberal order is remarkably recent. While liberal internationalism has an old pedigree, the consensus that Washington presided over an order where liberal means served liberal ends with liberal results is only a few decades old. A genealogy is needed, the tracing of its origins and development as a concept. For with genealogy – the excavation of the roots of an idea – we can learn why the vocabulary and mytho-history of liberal order appeals to a certain caste of mind. By digging into its prehistory, we can identify what historical shifts and problems gave rise to it. And we can uncover the silences, contradictions and evasions that bodyguard the concept.

Closer inspection reveals problems. Liberal international order does not deal adequately with what it is supposed to be defined and organized against. What is illiberal order? The concept of liberal order distinguishes the American Century from other kinds of domination, ones that were based on arbitrary power and imperial diktat. This is not just historically suspect. Something more fraught is going on among the devotees themselves. A closer look suggests that the visionaries of liberal order are also attracted to empire and the privileges of hegemony. They desire what amounts to a world monarch. Proponents of liberal order hold up the idea of a world hegemon that voluntarily binds itself in constraints through an enlightened settlement ‘after victory’, thereby winning legitimacy and international concord. Yet they also cut against this, either underplaying the history of continuous great power rule-violation, or arguing openly for superpower privilege without attempting to reconcile it with the claim of a rules-based order. Time and again, they call for the USA to exercise discretion beyond the rules, justifying illiberal means in pursuit of liberal ends. Thus, liberal order visions lose sight of a longstanding dilemma in American arguments over foreign policy, for which there is no easy resolution – namely, that a republic continuously pursuing dominance and expansion abroad assumes the form of an empire. And this, in turn, threatens liberty at home.

Before we explore these problems, it is important first to set out the idea of liberal order, as clearly and as fairly as possible. This is not easy. For the idea itself, as it is articulated and defended, is a slippery one. Looking to express an aspiration, it projects it back into history. Like the order it valorizes, it is a moving target that ducks and weaves against close scrutiny. It floats like a butterfly, even if it rarely stings like a bee.

The Order in Theory

There are many moving parts to the liberal order hypothesis. The genre appears in numerous forms, from op-ed and academic articles to manifestos and book-length studies. At the core of it is a mytho-history. It claims that the USA in its hour of mid-century triumph rescued the world. It created a new system of international relations, and subordinated itself to it. The new order was fundamentally sound. It was so successful that its beneficiaries have forgotten its benefits, and will learn to miss it.

The hypothesis proceeds as follows. It begins in the mid-twentieth century with the coming together of two forces, the precipitate rise of the USA as a result of a world war that devastated competitors, and the ascent of liberalism. The story arc typically begins around the ‘Truman moment’, President Harry Truman’s ‘blueprint for a rules-based international order to prevent dog-eat-dog geopolitical competition’.5 The order’s intellectual roots lay in a body of ideas that were anticipated earlier. Partly, it can be traced to the philosopher Immanuel Kant’s vision of universal peace, whereby nations subordinate themselves to principles and institutions that make it possible. It was anticipated also, decades before, by President Woodrow Wilson, and his doomed commitment to cooperative internationalism in the wake of the First World War. The idea was then hammered out into achievable form, in the matrix of the Second World War and through the tough-minded idealism of President Franklin Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Centre stage were their wartime pronouncements about the world to come, the ‘Four Freedoms’ speech, the Newfoundland Declaration and Atlantic Charter of 1941, the United Nations Declaration, as well as the creation of new institutions, such as the Bretton Woods financial settlement. The emerging order – and the wider cause of lasting American internationalism – was then consolidated by Washington (with encouragement from London) through celebrated words and deeds, Churchill’s ‘Iron Curtain’ speech at Fulton, Missouri in 1946, the Truman Doctrine of 1947 and the creation of NATO in 1949. The new security system was anchored in formal collective alliances in Europe, and bilateral ones in Asia. The new political economy was anchored in global institutions like the World Trade Organization (WTO), the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

In accounts of the post-war liberal order, many or all of the following features appear, though with varying emphasis: the rule of law and the supremacy of ‘rules’, humanist globalism and humanitarian development, free trade, multilateral cooperation, and the security provision of the USA, principally through its permanent alliances, and a commitment to liberal progress through the advocacy of democratic and market reform. Its institutions span the United Nations, NATO, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), then the WTO, the IMF and the World Bank. Overwhelmingly, the emphasis falls on the edifying, consensual side of world-ordering, on its continuity and coherence, rather than on its interruptions, contradictions and killings.

The order’s admirers claim, on its behalf, a large share of credit for the good things that followed. These include the absence of major war, economic growth, the reduction in trade barriers and successive waves of democratic and free market reform. Liberal order stood for transcendent values. It is the ‘single most consistent theme’ in American statecraft over seventy years, standing for ‘political liberalism in the form of representative government and human rights; and other liberal concepts, such as nonaggression, self-determination, and the peaceful settlement of disputes’.6 In their visionary world-making, the order’s founders were heirs to the enlightenment tradition, seeking out and advancing a common interest among nations, realizing its promise for the first time through effective mechanisms of governance – and power projection – abroad. The order, proponents argue, embodied also a pattern of behaviour, a ‘system of norms, institutions, and partnerships’ whereby, under the hegemon’s stewardship, collective cooperation trumped competition for relative advantage, significant shares of sovereignty were ceded for the benefits of collective action, as global consensus spread.7 The order has also been described as a system of ‘embedded liberalism’,8 with open markets, institutions, cooperative security, democratic community, progressive change, collective problem solving, shared sovereignty and the rule of law. It provided valuable public goods, like the freedom of the seas and the global commons. It created an ‘open, rule-based international economy’. These were ‘world historical advances’.9 Such an amalgam of power and social purpose reduces insecurity, inhibits self-aggrandisement and discourages bids for hegemony. The ultimate logic is one of pacification through benign expansion. A world ‘with more liberal democratic capitalist states will be more peaceful, prosperous, and respectful of human rights’.10

To say ‘liberal’ is not to mean ‘soft-headed’. According to proponents, the founders were not utopians but hard-headed idealists, pursuing enlightened self-interest. The liberal order as it is offered is not the same as the pre-war abstract and pacifistic idealism that was assailed by realists such as E. H. Carr. In fact, its theoretical foundation is part liberal, part realist. Today’s defenders argue that the pragmatic application of power is a necessary foundation of effective institutions, which in turn redefine relations between states.11 The order was premised on the ambition that countries could cooperate as rational states operating under conditions of anarchy, and, through collective effort, turn ‘anarchy’ into ‘society’. Because American hegemony offered leadership without overbearing dominance, it created ‘a consensual order undergirded by some mixture of rationalist calculations of material self-interest and convergent values, affinities, and identities’.12 Liberalism does not preclude coercion or violence. But minimally, a liberal order constrains and alleviates violence, so that those who wield force do so reluctantly, infrequently and with great self-restraint, striving to make their violence as consistent with liberal principles as possible.

As well as America’s unprecedented level of material power and reach, what were the alleged sources of the order’s stability? One answer is that the institutional framework itself took effect. Another version of the liberal narrative, reflecting the ‘bottom-up’ emphasis of the new liberalism, is that the superpower’s domestic political and constitutional character was the decisive element.13 It was liberal because its chief maker, America, was liberal. If a stable hegemonic order requires authority, which legitimises hierarchy, liberal powers are better at acquiring authority because of their own domestic constitutional limits on abuses of power, which make them more trustworthy international rulers. Here in the American Century was an order flowing from its own liberal political essence, of hegemony as distinct from empire, leadership as distinct from imperial domination.14 Or in the words of one admirer, the modern ‘rules-based order’ is an ‘an attempt by a community of like-minded democratic states to “domesticate” the international system in such a way that it becomes more like an international society, based on a clear set of rules, to try and prevent revisionist behaviour’.15 This apparently succeeded until recently. The USA gave other states an equity stake in the order, reshaping interests to create a progressive equilibrium. Optimists believed – or hoped – these qualities would make the order robust against the rise of new rival powers.16

So this was, allegedly, a new kind of dispensation. It worked through a synthesis of benevolent internationalism and a preponderance of power, one that was post-imperial yet ordered, anchored in institutions yet relying also on a superpower’s coercive strength. Thanks to the institutional depth and reach of American power, major war was taken off the table in traditionally belligerent power centres of the globe, specifically, continental Europe and Northeast Asia. Favourable settlements – concerning trade, diplomacy, alliances and patterned ‘summitry’ – locked in enduring patterns of consensual behaviour. Diplomatic access and ‘voice opportunities’ were extended to weaker states. For all the different shades of opinion, all unite in some general propositions. The USA, they argue, as global leader used its power and its sapience to create a new dispensation after the Second World War. It created institutions, permanent alliances, open markets and a general condition of consensual and cooperative behaviour, regularity and rules and rule-following. In turn, this system bore fruit. It transformed international life in ways that were fundamentally good, relative to an earlier more violent history of cut-throat power politics. They credit it with every significant benefit of the post-war years: the absence of major conflicts, the slow and limited proliferation of nuclear weapons, economic growth, freer trade, more recently increased life expectancy, and the retreat of poverty in the Global South. They argue that to remain civilized, the world permanently needs what arose in the late 1940s, a level of American power, unrivalled and unmatched, but carrying the mission of world leader, even if they disagree on whether this is still possible.

This all raises the question: what would an illiberal order look like? Liberalism itself is a contradictory and multisided tradition that only draws coherence from what it is said to be against. The liberalism recalled today was developed between the 1930s and the 1950s as the ‘constitutive ideology of the West’, especially through struggles with Axis then Soviet totalitarian menaces, against which it was framed as their ideological antithesis.17 It came to be associated with democracy and freedom from tyranny. Undergirded by American power and direction, the new order worked towards a democratically inspired and commercially linked world, one of openness, cooperation and regularity. It marked a great, deliberate turning away from the older world of colonial empires, trade blocs and spheres of influence, which had in turn given rise to totalitarianism and genocide.

An illiberal order would presumably be the opposite of these things: politically and economically divided and closed, authoritarian, uncooperative, coercive beyond liberal boundaries, and disrespectful of rules and norms. It would be a system of oppressive overlordship. A clue to its shape, it is said, lies in today’s hostile authoritarian powers, which are bent on revising world order, driven primarily by a malign ideology. They are led by Russia principally, by China and Iran, and include designated ‘rogue’ states like North Korea. Illiberalism advances, too, within the world’s democracies in the form of domestic insurgents. Together, they make up a counter-enlightenment that is on the march. But what do they all have in common, apart from hostility to American leadership? A unifying theme, it is said, is the contrast with the nineteenth century as the historical antithesis of the liberal order, the world it claims to have repudiated and dismantled. Here there is an ill-defined enemy, loosely termed ‘geopolitics’.18 Proponents claim that the new liberal order supplanted not just power politics, but an older form of power politics. Statements of US officials give some clues about the outlines of the pre-liberal order that Washington believes it replaced. According to presidential candidate Bill Clinton in 1992, ‘the cynical calculus of pure power politics … is ill-suited to a new era’. Or, in the words of President George H.W. Bush as he announced military action in the Persian Gulf War, the USA sought ‘a world where the rule of law, not the law of the jungle, governs the conduct of nations’. The features of that old world were territorial spheres of influence, imperialism or economic protectionist blocs. Spheres of influence, or the division of the world into zones dominated with a free hand by great powers, is a particular focus as an antithesis of liberal order. While encouraging Georgia’s eventual accession to NATO, pledging support to its territorial integrity and rebuking Moscow’s claim to a ‘zone of privileged interests’ in former Soviet lands, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton averred: ‘The United States does not recognize spheres of influence’ and President Obama insisted that ‘The days of empire and spheres of influence are over’. Secretary of State John Kerry criticized Russia’s seizure of Crimea in similar terms: ‘You just don’t in the 21st century behave in 19th-century fashion.’ In some way, there was a fundamental systemic change, in shared assumptions of what behaviour is legitimate and conceivable, reflected for instance in a supposed post-war norm against territorial annexation.19

Gideon Rose offers a similarly neat encomium about the ‘team sport’ that was ‘the liberal international order that the United States has nurtured over the last seven decades’:

[America’s mandate was] to consolidate, protect, and extend the liberal international order that the United States helped create after World War II. Reflecting on the nightmares of the interwar period, when unregulated markets and uncoordinated behaviour led to economic disaster and the rise of aggressive dictatorships, Western policymakers in the 1940s set out to construct a global system that would prevent such problems from recurring. They ended up doing a masterful job, weaving together several components of domestic and international affairs into a unified, expansive, and flexible structure that has proved more durable and beneficial than they could ever have imagined.20

Because it is rhetoric of praise, the literature tends towards ambitious generalization and, at the same time, shields its subject from blame. Disasters that accompanied the same system of hegemony, like the War on Terror, free market ‘shock therapy’ in Russia or the global financial crisis, are explained away reassuringly as departures from the same masterful system that was designed to prevent dangerous adventurism or unstable finance.

To preserve and enforce the order, the panegyrics advocate the continuation of US armed supremacy. If the order was a security system created and underpinned foremost by American might, then it requires sustained US military preponderance, striking power and a ‘global footprint’,21 reflecting a consensus among primacists that the USA self-evidently needs far-flung military power beyond challenge. In a representative collection of essays, including by Samantha Power, Francis Fukuyama, Robert Kagan, Niall Ferguson, John Ikenberry and Charles Maier, the authors agree that ‘the United States should be a leader in the international system’, and that ‘none of the contributors propose to reduce the military spending significantly or allow US superiority to erode’.22 Even a system organized around cooperation, it seems, ultimately rests on one state’s overwhelming capacity to kill people and break things. This is an observation we will return to. For if, like all other hegemonies, this one relied for its authority on the implicit potential for it to be imposed by force, and if this was in fact exercised often, then its uniqueness is in doubt.

If the liberal order hypothesis were to hold up as an account of US statecraft, how would we recognize it? What are the tests or ‘observables’? We would expect to see, first, regularity. Washington would bind itself by its obligations under international law and according to the will of international institutions. It would not only do so for most of the time; crucially, it would do so even when it was reluctant, when its interests pointed in a different direction. We would expect to see Washington dismantle barriers to free trade. It would do so even to the point where it did not suit America’s desire to remain economically preponderant. Washington would consistently strive for a level playing field for foreign industries and commerce. We would also expect Washington to use force, but reluctantly, discriminately, under careful scrutiny, in deference to liberal humanitarian norms and the laws of armed conflict. We would expect that Washington would regard its allies as an ideal-typical hegemon would do, picking up the bill while refraining from coercion, and as ‘autonomous, coordinate units enjoying juridical equality (status, sovereignty, rights, and international obligations) regardless of differences in power’.23 In sum, if liberal order is to mean something historically, it cannot be just a matter of convenience but one of inconvenience. The superpower would mostly submit itself to the demands of liberalism in circumstances where it would prefer to do otherwise, and behave differently than it otherwise might. If this all sounds ambitious, it is. For the most part, it is a test that liberals have set themselves.

Other Than That, Mrs Lincoln: Silences, Omissions and Ruptures

For its enthusiasts, liberal order is designed primarily to serve a political need in the present, just as this critique is. To engage with it is to contend with a series of potted histories about American power in the world. These histories skate over some obvious historical problems.

Those in favour of liberal order tend towards the reverential and the absolute, regarding an order as sacred and aberrant behaviour as profane. In doing so, they write out large swathes of history. Until recent irruptions, we are told, America stood for ‘open borders and open societies’,24 built by Americans who ‘are less interested in ruling the world than they are in creating a world of rules’,25 even though the latter presupposes the former. Ivo Daalder, former academic, President of the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, and former Permanent Representative on the council of NATO, made a typically absolute claim, uncluttered by historical detail: ‘For 70 years, the United States has led the global effort to promote democracy, human rights and the rule of law.’26 That there was variation, to say the least, in the extent of Washington’s humanist commitment goes unmentioned. It would be instructive to try this argument out before a Latin American audience.

This is history served up to bolster a sense of mission. As Secretary of State Hillary Clinton recalled in 2014:

After the Second World War, the nation that had built the transcontinental railroad, the assembly line and the skyscraper turned its attention to constructing the pillars of global cooperation. The third World War that so many feared never came. And many millions of people were lifted out of poverty and exercised their human rights for the first time. Those were the benefits of a global architecture forged over many years by American leaders from both political parties.27

In this milk toast version of the past, the darkness of history recedes. Only two wars are mentioned: the victorious world war of mid-century, mentioned as a book-end rather than a process, and another world war that wasn’t. Other wars, also central to ordering, are pushed to the margins. Maximum emphasis lies on cooperative leadership and peaceable acts of creation. Minimal emphasis goes to coercion, to the point of near silence. On two frontiers, continental and then global, the rough power politics of history, from genocide of native Americans to the brutal struggles of the Cold War, are erased. Other possibilities go missing in action: that major war was averted by the terror of nuclear threat and still came close to erupting, that international institutions, the expansion of capital or aid programmes entrenched as well as alleviated poverty, or that deadly competition continued to define international politics. The rise of the USA is neatly simplified into a benign engineering project.

It is not just politicians who offer these cleansing summaries of history. It is also a standard credo of accomplished and decorated public intellectual figures. Reacting to the election of Trump, the diplomatic historian Jeremy Suri offered a similarly upbeat prehistory, charging that Trump is plunging the world into a great regression, by ‘launching a direct attack on the liberal international order that really made America great’. The elements of this order include ‘a system of multilateral trade and alliances that we built to serve our interests and attract others to our way of life’. ‘The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in Europe and a web of alliances in Asia and the Middle East’, he explains, ‘contained aggressive states, nurtured stable allies, and promoted democratic reforms when possible.’ ‘Other institutions’, such as ‘the European Recovery Program (the Marshall Plan), the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (now the World Trade Organization), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the World Bank’, enabled the USA to lead ‘a post-war capitalist system that raised global standards of living, defeated Soviet communism, and converted China to a market economy’.28

Like Clinton’s tribute, Suri offers a strangely bloodless retelling of history. It is a euphemistic rendering of the Cold War and the actual practice of anti-Soviet containment by the superpower and its proxies. Napalm, Bay of Pigs and the Contras fade to the background. Repression all but disappears. Missing too are the anti-communist purges of Indonesia’s General Suharto in 1965, a massacre of perhaps one million people, with the active help of CIA and US embassy staff. Regarding Latin America, support for death squads and revelations about Operation Condor go unmentioned, the US training programme for security forces in torture and blackmail techniques for twenty-five years. Washington, it would be fair to say, often chose to prioritize other interests above democratic reforms. The enormities of the War on Terror also disappear, such as rendition and torture. Unstable allies go missing in action, from Saddam Hussein to General Yahya Kahn to the Afghan Mujahideen to Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to Mohammed Bin Salman al Saud. The corruption and protectionism of China’s conversion to a market economy – its intellectual property theft, massive subsidies for state-owned enterprises, and barriers to market entry – here disappears. That this retelling should come from a distinguished historian of American diplomacy suggests how seductive the vision of an earlier and better order has become.

There is a problem of time and historical memory in liberal order discussion. A stock-standard periodization of the order’s life is ‘seventy years’ or ‘seven decades’. It harmonizes with NATO’s recent anniversary and hints at a biblical completeness. This suggestion of an unbroken unity in the Pax Americana from 1949 until the recent past is appealing. It gives added sanctity and a sense of stability to the order. By heightening a sense of stability and continuity, it portrays the Trumpian interruption as a great and wrenching intrusion of time into paradise, like Anglo-Catholic memories of a tranquil Christian England thrown into chaos by the stripping of the altars. Today, the foreign policy establishment reveres global partnerships and institutions as almost sacred. NATO was ‘the core of an American-led liberal world order’.29 At times, the literature borders on a state of rapture. Former Secretary of Defense Ash Carter likened a joint news conference of presidents Trump and Putin to ‘watching the destruction of a cathedral’.30 With Trump in the White House, liberal order enthusiasts hope the torch will pass to other allies, as figureheads of enlightened internationalism. At the 2019 Munich Security Conference, Daalder hailed German Chancellor Angela Merkel as ‘The Leader of the Free World’, whose speech on the need for solidarity in upholding the rules-based order deserved ‘thunderous applause’.31 Only now, ‘for the first time in its history’, claims former diplomat and professor Nicholas Burns, is NATO threatened by ‘the absence of strong, principled American presidential leadership’.32 What Burns makes of the forceful critiques and browbeating of NATO allies made by most presidents from Eisenhower to Obama is not clear.33 If the main difference now is that Trump berates allies in public while still materially reinforcing NATO, then the order’s bedrock is fragile indeed.

Despite depictions of NATO as a moral community built around shared liberal values,34 and hyperbolic claims that US coercion of NATO allies is unprecedented, the reality is that hierarchical imposition and demand have been part of transatlantic relations ever since the alliance’s founding. In 1954, Secretary of State John Foster Dulles threatened Europe with an ‘agonizing reappraisal’ of alliances. In 1963, with threats of abandonment, President John F. Kennedy coerced West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer into supporting US monetary policy and offsetting the balance of payments deficit created by America’s deployments in Europe.35 In 1973–4, President Richard Nixon and his National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger suspended intelligence and nuclear cooperation with Britain to punish non-cooperation over a US-initiated Declaration of Principles and the privacy of bilateral and UK–EEC discussions. The ‘special’ Anglo-American relationship has featured multiple episodes of arm-twisting. In 1982, when President Ronald Reagan slapped sanctions on foreign companies, including British ones, that constructed a Soviet pipeline through Poland, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was ‘deeply wounded by a friend’.36 Despite Britain spending blood and treasure in Afghanistan and Iraq to support the War on Terror and cement its standing in Washington, President Obama bluntly threatened that departing from the EU would place the UK at the ‘back of the queue’ when seeking a bilateral free trade agreement. And the USA used the threat of abandonment to persuade allies and clients to cancel their nuclear programmes, including West Germany, Japan and Taiwan.37

That transatlantic solidarity leads easily into hierarchical demand is demonstrated by the fact that even some of today’s leading admirers of NATO have also explicitly issued transactional demands against its members, cautioning that failure to contribute sufficiently will (and should) result in its extinction. The avowed Atlanticist Anne Applebaum laments the unravelling of the transatlantic alliance and Trump’s demand that its members dramatically increase their contributions under pain of possible American withdrawal. For her, ‘security and defence organizations’ are ‘special and inviolable’, without which the USA ‘ceases to be a force in Eurasia. The US military will have trouble projecting military power into the Middle East or Africa’, leaving China to predominate and set the terms of trade. Security organizations were ‘the basis for American military power, as well as for American wealth and prosperity’.38 Yet only four years previously, Applebaum argued that President Obama ‘does have the power to relaunch the Western alliance. He has all of the cards – the USA contributes three-quarters of NATO’s budget – as well as the ultimate argument: if the Western alliance, as currently constituted, no longer wants to defend itself, America can always leave.’ Significantly, this was at a time when Russia had already seized Crimea and was at war in Ukraine, so it was probably not a growing eastern threat that drove Applebaum to alter her stance. Rather, the confusion of this critique reflects a tension in American transatlantic order-building, to regard the alliance as sacred – or ‘eternal’, in Obama’s words – while coercing its members with conditional demands. It could be objected that Obama and Applebaum, unlike Trump, would only make such explicit threats in order to preserve NATO. Yet for such threats to succeed, they would need to be credible, beyond bluffing. Having urged the White House to change European behaviour by explicitly using the threat of abandonment, Applebaum recoiled when it actually did so.39

Consider also two leading advocates of liberal order, Ivo Daalder and Robert Kagan, who in the age of Trump champion the cause of NATO’s endurance and Germany’s special place within the Euro-Atlantic community. Fearing its unravelling, Kagan spoke of the ‘democratic alliance that has been the bedrock of the American-led liberal world order’,40 while Daalder argued that ‘Allies need reassurance. They want to hear, as President Obama said in Estonia following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, that Article 5 “is a commitment that is unbreakable. It is unwavering. It is eternal”.’41 It was not ever thus. In 2004, when Berlin refused to send troops to Iraq to support a war it had consistently opposed, Kagan and Daalder sounded if not a Trumpian note, certainly a coercive one, in their joint denunciation of allies’ recalcitrance.42 They referred to NATO members in shudder quotes as ‘allies’. They asserted that if European allies didn’t pull their weight – and the Iraq campaign was not even a NATO operation – Americans should doubt NATO’s value: ‘There is the question of whether there is any meaning left in the term “alliance” … If France and Germany are intent on saying no, then future American administrations, including Kerry’s, will have to reconsider the value of the alliance.’ With the superpower confronted by growing civil strife and resistance in Mesopotamia, the two Atlanticists did not characterize the alliance as they do today, as the bedrock of the American-led liberal world order that deserved eternal American commitment. They wrote at the height of the War on Terror, when the initial confidence of the Bush II administration was giving way to anxiety that the ambitious bid to reorder the Greater Middle East would be more costly and difficult than realized, and that internationalizing the burden would be needed. Growing pressure on American power revealed even among enthusiasts for liberal order the closeness of ordering with hierarchical coercion. Trump’s subsequent public denunciations of the alliance on similar terms, and his insistence that US commitment was conditional, was a dramatic shift in style but not in substance.

NATO’s history itself involved bargains with authoritarianism, even as its presence in Europe was a vital pillar of anti-Soviet containment. For decades, it included authoritarian regimes like Portugal and Greece. And while the membership of Spain under the repressive regime of General Francisco Franco was vetoed against Washington’s preference, it was still informally linked to the actual transatlantic defence structure through the Pact of Madrid and a basing agreement. Turkey’s increasingly authoritarian regime is a standing embarrassment to the suggestion of a liberal, democratic club. Expansion in Eastern Europe has demonstrably not liberalized Poland or Hungary. NATO’s own military campaigns have not always enhanced liberal values. In Libya, the revolution facilitated by NATO’s airstrikes led to the collapse of the economy, rival parliaments, the proliferation of torture and open-air slave markets. In the Balkans, intervention against genocide inadvertently led to counter-atrocities. As reported by the Independent International Commission on Kosovo, established in 2000 in the aftermath of the Kosovo war, NATO’s international presence failed to prevent reprisal ethnic cleansing by the Kosovar Liberation Army.43 The various forces that brought NATO together – anti-Soviet communism, liberal values, the European desire for cheap security and the US desire for transatlantic primacy – were not always in harmony. So the beguiling claim of seventy continuous years of order organised around liberal principles, and enshrined in institutions like NATO, does not hold up. The world before the invention of the term ‘liberal order’ was a foreign land, where they sometimes did things differently.

A glance at the genealogy of liberal order raises a further difficulty, that this is a largely retrospective construct being imposed upon a historical era, in order to intervene in present struggles. While its proponents trace it as a concept from the post-war era, the Pax Americana, and regard that order’s value as transcendent and universal, as an article of faith its provenance is relatively recent. As Adam Garfinkle cautions, there is a distorting temptation in post hoc naming of a thing that seems threatened, to ‘exaggerate the virtues of what is being named, and to round off any pesky dissonant edges from it’.44

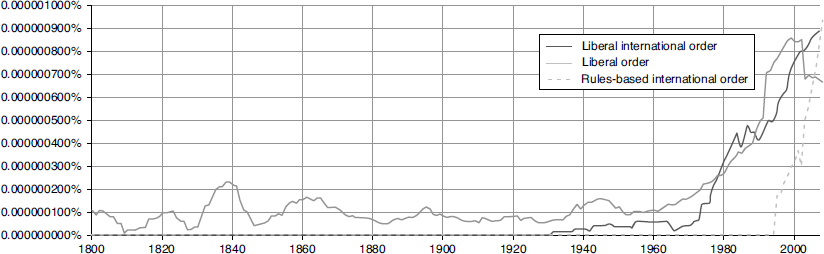

Using ‘Google Ngram’, Joshua Shifrinson45 created a graph llustrating the usage of the phrase ‘liberal international order’ from 1800 to 2008. As Shifrinson observes, the increasing use of the term coincides closely with the late years of the Cold War. It then takes off dramatically. Similar patterns emerge from searches based on other variants of the phrase. For example, usage of the phrase ‘liberal order’ rises, while the spike in usage of ‘rules-based international order’ is even more sudden and recent (see Figure 1).

So ‘liberal order’ as a phrase, and as complaint against departures from it, can be backdated to two historical intellectual moments. The first significant increase took place in almost exact correspondence to the rise in anxiety over US decline and the coming of multipolarity. In fact, two of the leading purveyors of ‘liberal order’ as a concept, Robert Keohane and Joseph Nye II, also led the debate over whether a liberal international system would endure even after American hegemony waned.

Figure 1 Usage of the phrases ‘liberal international order’, ‘liberal order’ and ‘rules-based international order’, 1800–2008

Source: Chart produced by Joshua Shifrinson on Google Ngram Viewer, reproduced here with permission.

The more recent episode involved critiques of the Bush II administration and the War on Terror, and a desire to reclaim the word ‘liberal’ as an honourable and American tradition, rather than the dirty word it had become in conservative politics. The critique, spearheaded by Ikenberry, was provoked by the Bush presidency’s swaggering unilateralism, contempt towards allies, abrogation of international agreements and recourse to extraordinary rendition and torture. Those critics relied upon a sharp distinction between liberal and imperial orders. It was then the War on Terror, not Trump, that was the great interruption. This in itself contradicts the later claim that there were seventy years of order, whole and integrated, until the unprecedented Trumpian lapse.

One pronounced difference separates ‘world order’ literature of the Cold War and post-Cold War eras. Rhetoric about American security strategy in both eras shared a common commitment to a ‘free world’ and the exceptionalist assumption of a USA with a unique mandate. Yet statements about an American-led world order during the long security competition with the Soviet Union were both distinctly religious and enemy-centric. It made explicit references to God, to divine will and to a historical mandate handed down from heaven, and to a dangerously evil opponent. It deployed a wider language of faith, long before the Cold Warrior President Ronald Reagan courted the evangelical Right. Dean Acheson, one of the principal architects of post-war diplomacy, was the son of an Episcopal bishop with a keen missionary sense of America’s responsibility, just as two of his successors as Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles and Dean Rusk, were sons of Protestant ministers. The intellectual architect of anti-Soviet containment, George Kennan, spoke of the need for a ‘spiritual vitality’. The signature Cold War strategy document NSC 68 exhorted the USA to mobilize a ‘spiritual counterforce’ against the fanatical creed of communism. The influential Secretary of State John Foster Dulles in explicit religious terms advocated a unifying American mission of belligerent anti-communism. Cold War authoritarians such as Senator Joseph McCarthy and FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover justified their actions around the cause of patriotic Christianity against atheistic communism. Cold War liberal hawks, too, drew on the language. Running for president, Senator John F. Kennedy spoke of ‘a competition of ideologies, freedom under God versus ruthless, Godless tyranny’.46 Even Henry Luce’s clarion call for an American Century, a rationale for world-ordering that comes much closer to today’s paeans, promoted religious revival as central to victory in the Cold War.47 The rhetoric of spiritual battle, and the contest for Christian civilization against atheistic barbarism brought its own demagogic excesses. It also had sinew. As rhetoric and as an agenda for action, it brought effective mobilizing power. The referent object being offered today, the abstraction of liberal order, may not prove as stimulating. As Stephen Wertheim cautions, ‘confronted with a choice between “America First” and “the post-war international order”, voters will opt for what they understand and identify with, what evokes a better future. Does anyone really think “the order” will win?’48

By contrast with the era of blood, fire and judgement, the panegyrics of our time are highly secular. International politics rages under an empty sky. This is not to speculate about the personal theologies of the ‘liberal order’ faithful. Rather, it is to note a remarkable retreat of overtly pious language from their public offerings about America’s global mission. It may be that this shift is largely due to the changing sociology and manners of the US security establishment, towards greater heterogeneity, for whom religious justifications of American statecraft are irrelevant or best kept private. Ostentatiously devout worshippers are no longer as numerous amongst the establishment as they once were. The socially narrower and more pious world of George Kennan, the religiously observant author of the doctrine of anti-Soviet containment, would be rarer now. Indeed, at times they define liberal order itself as the antithesis of obscurantist religion and blood myths. Some versions of the literature move so far in this direction that they present world order in mechanical and bloodless terms, that play down or even deny active power struggle. Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Security Affairs Kurt Campbell, for instance, framed American primacy in Asia as an ‘operating system’.49 The language of god and struggle is replaced by a computer metaphor, with the USA retaining authority as the supreme technician. Such an image appeals because it naturalizes American power, imagining the world re-organized around elevated principles, stressing the commonality of values, the harmony of interests and the obvious goodness of the design. Who could object to a well-functioning operating system? Yet who would fight for it?

As well as replacing an intense cause of spiritual struggle with a less compelling one, foreign policy minds lack another source of coherence and mobilization: a defining super-enemy. While China is richer and materially stronger, not even it poses the kind of universal ideological challenge of Soviet Marxism-Leninism. The Manichean worldview historically led to egregious errors, for instance in long denying the possibility of a Sino-Soviet split in the communist world. It also held out the advantage, though, of recognizing the reality of violent struggle and justifying awkward coalitions. It offered the equation of necessary illiberal means in pursuit of liberal ends. The USA could take part in compromising geopolitics, with the assurance of an ultimate moral end. With its specified adversary and eye for what anti-communists had in common, it offered a certain geopolitical coherence. With the defining enemy and single global struggle gone, it is more difficult for liberal order proponents to rationalize the linkage of means and ends. Cold Warriors could appeal to compatriots to focus on what they were against, and could rationalize illiberal behaviour as a necessary lesser evil, which could eventually reform authoritarian client states.50 Religious anti-communism supplied the rationale for intervention in the Italian democratic election of 1948, the kind of detail that escapes more recent encomiums to the order. The CIA helped the electoral defeat of communists by funding anti-communist parties, forging documents to discredit the communist party, and warning Italians who publicly supported that party that they would be barred from entering the USA. For the sake of liberalism in the long term, the USA exercised its privileges. If the deliberate subversion of a democratic election abroad by means of fake news, bribes and coercion represents the antithesis of liberal world order, as Trump’s critics now suggest, then Washington attacked that order in the period of its creation. If Washington in practice accepted that noble ends warranted illiberal means, that rationale assisted the creation of coalitions with illiberal forces, like the papacy.

Similar means-ends rationales also enabled more ironic alliances. One embarrassing counterpoint for the mytho-history of liberal order is America’s long post-war tradition of collaboration with Islamist militants who are driven by medieval nostalgia, from President Dwight Eisenhower’s welcoming of the Muslim Brotherhood organizer Said Ramadan into the Oval Office, to Brzezinski’s ‘arc of Islam’ to contain the Soviets from northeast Africa to Central Asia, to US-sponsored jihads against Russian clients from Afghanistan to Bosnia, and its inadvertent support of Islamist militias in Syria.51 At least on earlier occasions the USA knew in advance who it was supporting. This is not a commentary on the wisdom or folly of such measures. It is to suggest that a ruthless and more focused mindset, which at least confronted the problem of bargaining with necessary evils, has yielded now to a muddled one.

The purveyors of liberal order panegyrics realize, in their asides, that there are historical and conceptual difficulties with the global design that they advance. Many have served in government. They know that even the simplest things are difficult. There are, they admit, other mechanisms of order that lurk at the edges of the US-led one. There were, they admit, hubristic blunders, like wars of liberation or market fundamentalism that were somehow causally unrelated to the order, even if policymakers regarded them as central to world-ordering and a liberalizing mission at the time.52 The world had its imperfections and errors – the limits of the UN’s capacity and the hegemon’s writ – and there were ‘mistakes’ like Bay of Pigs and Vietnam.

As soon as such difficulties surface, however, they are promptly separated from and in quarantine in the order’s essence. The most self-aware panegyrics do not deny the negative parts of history. Rather, they separate them, like defence counsel excluding things from the pleadings. Darker behaviours were aberrations from liberal order, not features or pathologies of it. When things went wrong, a world-historical transformation, suddenly, was bounded and constrained, and errors under the order could not be linked to it or its epochal ambitions. Things that happened outside the West are marginal, suddenly, because it is a story really about what happened inside the West, despite proponents’ other claims about global leadership and despite emphasis on a global military footprint, or on invigilating the Middle East, or on the vital importance of humanitarian effort or military strikes outside the West. With throats cleared, the core story proceeds undisturbed. Large parts of post-war history that don’t fit the narrative are quickly dispatched – yet return to haunt the retelling. John Ikenberry claims that in order to keep Europe, Asia and the Middle East open to trade and diplomacy, empire was repudiated, and ‘with some important and damaging exceptions, such as Vietnam, the United States has embraced post-imperial principles’.53 There is an ‘apart from that, Mrs Lincoln, how was the show?’ quality to this argument. Vietnam was one of the USA’s most intense and sustained post-war undertakings abroad, waged to preserve a system across seas and continents. As we will see, it is better understood not as an atypical lapse from the order into atypical, imperial excess, but as a sincere attempt at world-ordering to uphold that very world, a project driven by both liberal and imperial impulses, and one that reflected the tensions between them.

Occasionally in the literature, the narrative is ruptured, only for the order as a noble cause to reassert itself. In an attempt to apply sober measurement to the world order debate, Joseph Nye argues:

The mythology that has grown up around the order can be exaggerated. Washington may have displayed a general preference for democracy and openness, but it frequently supported dictators or made cynical self-interested moves along the way. In its first decades, the post-war system was largely limited to a group of like-minded states centred on the Atlantic littoral; it did not include many large countries such as China, India, and the Soviet bloc states, and it did not always have benign effects on non-members. In global military terms, the United States was not hegemonic, because the Soviet Union balanced US power. And even when its power was greatest, Washington could not prevent the ‘loss’ of China, the partition of Germany and Berlin, a draw in Korea, Soviet suppression of insurrections within its own bloc, the creation and survival of a communist regime in Cuba, and failure in Vietnam. Still, the demonstrable success of the order in helping secure and stabilize the world over the past seven decades has led to a strong consensus that defending, deepening, and extending this system has been and continues to be the central task of US foreign policy.54

To his credit, Nye acknowledges the danger of ahistorical romance. At the same time, the order’s supporting mythologies prove resilient. Illiberal behaviour and what appear as ‘cynical, self-interested moves’ (even in what he calls a ‘rules-based system’) are lapses that are separate from ordering rather than inherent to it, and so hardly bear on the overall appraisal. The statement concludes with a ringing confidence that his caveats and qualifiers do not warrant. American hegemony is only a recent development, not a seventy-year ‘system’ of power, as Nye observes, and world order since 1945 was defined partly by the checking of America’s bid for dominance. Its sphere was limited to the democratic, capitalist rimlands; it could not even prevail over smaller determined adversaries and its writ was circumscribed by large outside actors. Yet this leads to a non sequitur, that the record of curtailed hegemony and active resistance from rival powers is evidence for the need to extend hegemony further, in a world where multipolar competition is again returning. And, tucked into euphemistic phrases that almost slip past the eye (‘did not always have benign effects on non-members’, ‘a draw in Korea’) is a world of war and counterrevolutionary suppression.

Robert Kagan offers an important, and distinctively different, variation of the argument that serves as a point of entry into these problems. He makes an admission rare in the literature:

When it came to the application of force, in particular, there was a double standard. Whether they admitted it or not, even to themselves, American officials believed the rules-based order occasionally required the exercise of American power in violation of the rules, whether this meant conducting military interventions without UN authorization, as in Vietnam and Kosovo, or engaging in covert activities that had no international sanction.55

Exactly so. But with this acknowledgement, Kagan effectively concedes that by reserving the right to exercise illiberal means as a privilege, the hegemon was sometimes imperial. This points to an underexplored difference within the hegemon’s camp: while some insist on the order’s regularity, in means and ends, others are aware that the world is a conflicted place and defend the exercise of irregular methods for the greater good.

For war itself – as a bloody and illiberal process – fades from most of these visions. While the arguments regard America’s hegemonic military power and its alliances and far-flung presence as foundational to the order, they mostly avert their eyes from hegemon’s actual historical exercise of violence. Nuclear weapons are recognized as fundamental to the order, but it was their actual use against Imperial Japan in 1945 that demonstrated their destructive, genocidal and revolutionary power, arguably necessary to establishing deterrence in the first place. The absence of major war is credited primarily to American ordering, less so the fact that the USA was constrained in its capacity to order others by its adversaries’ own nuclear arsenals. Indeed, the constraining effects of nuclear deterrence depended on the failure of some of America’s non-proliferation efforts.

Panegyrics show a similar incuriosity towards how the USA acquired the very platforms for military power projection. Maintenance of the order is typically ascribed to a global military presence. Parts of that apparatus were created through decidedly imperial means. An awkward fact about the structure of planetary military power that enforces rules-based liberal order is that the archipelago of defence facilities was partly created through colonial dispossession.56 It involved the eviction (or duress) of native islanders in order to use territories, from the Chagos Islands to Guam, along with other annexed territories like Puerto Rico, the US Virgin Islands, the Northern Mariana Islands and American Samoa, whose indigenous peoples remain unenfranchised. The Obama administration went to some lengths to isolate Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama, the only Japanese premier to challenge the US military hold on Okinawa, isolating him with stony silence on the issue.57 Likewise, in Diego Garcia Britain expelled the population of 2,000 Chagossians to make way for a US airbase after London forced Mauritius to sell the territory in 1965, as a price of decolonization. The UK has continued to hold on to the territory, despite a non-binding motion from the UN General Assembly and an advisory opinion from the World Court that the dispossession was wrongful.58 The development of nuclear capability, too, took place through irradiating tests on the Pacific Proving Grounds, such as the Marshall Islands and Bikini Atoll. The order is supposed to have demolished the practice of land grabs. Yet such territorial annexations were also prior steps in the creation of a system of armed supremacy. It is awkward, too, because those enforcing the order insist that rising powers like China forgo the kind of colonial behaviour towards real estate that they themselves used in order to project power.

As the dark parts of war are marginalized in the story, note that there are also very few references to drones, and the recent creation of an armature of extrajudicial assassination. There is little reference either to the conduct of drone strikes, as part of what one military commander called ‘almost an industrial scale counterterrorism killing machine’ worldwide.59 Given the intent, violence and scope of this raiding, it can hardly be separated from the order. With the arrival of the standoff technology and the desire to liquidate terrorist threats without the burden of casualties or live captives, drone strikes became a prime method for taming and bringing unruly frontiers back into order. Yet the rapidly expanding extrajudicial assassination programme hardly appears in appraisals of the Obama presidency, the last administration credited with being, in principle, a liberal order builder, or in appraisals of the state of the order under Trump. While gallons of ink have been spilt on the levels of disharmony within alliances at summits, the actual practice of applied violence in the shadows almost disappears from the accounting. Type in ‘drone’, ‘assassination’, ‘killing’ even into lengthier assessments of the liberal order’s health – for example, the RAND study, the Aspen Policy paper, the CNAS report – and the return is either silence, or an anxiety that the technology is proliferating to dangerous adversaries. One of the few exceptions to this silence is the advocacy of US journalist and military historian Max Boot. For him, there is no painful trade-off. To defend the lofty values of cosmopolitan enlightenment, he advocates regular pacification by force, modelled along the lines of Britain’s North-West Frontier and America’s frontier wars.60 This at least is clear.

It is not just an aversion to bloody details that explains these omissions. It is an aversion to the contradictions within ordering. The notion of an order with complimentary and reinforcing parts is also suspect. In the immediate post-war period the paramount security of sovereign states was a defining principle, at least in word. The principle of non-intervention is at the heart of the United Nations Charter, and the General Assembly has reaffirmed and clarified it on multiple occasions. Yet more recent doctrines have stretched or upended it, advocating in certain circumstances the subvertion of state sovereignty. Coalitions without a mandate from the United Nations have arrogated the authority to pronounce an offending state’s sovereignty forfeit, in the name of humanitarian liberation. Again, some advocates of liberal order argue for a revival of the Reagan-era programme of financing electoral bodies, political parties, legislatures, independent media and labour unions, a programme that was directed in particular at hostile regimes.61 In truth, liberal order could be taken to prize either project, a revolutionary commitment to democratic expansion, or a system of global governance that provides reassurance to sovereign states, in the hope they will convert them in the long run.

In this picture, the causal claims and the relative weight to be given to power and ideas are not always clear. The exact relation between ideas, institutions and material capabilities shifts between and sometimes within the arguments of each panegyric. At times, the literature accords prime causal weight to a ‘package of ordering ideas and rules’, suggesting that those things bear a decisive force in creating a lasting and attractive order, independent of the distribution of material power and US advantage in other forms of power such as nuclear weapons. At other times, these ideas and rules must be underpinned by the material power of hegemon, ordering others by giving them rational incentives through institutions. As proponents of liberal order assume their conclusions and assert what they ought to prove, the power of institutions and norms is asserted but hardly demonstrated. As one critic asks: ‘Why are norms necessary to account for peace when US power preponderance would make it very difficult for any state or plausible coalition of states to match US capabilities in the near future; and when the nuclear revolution allows major powers to enjoy abundant security despite US hegemony?’62 The boundaries of the order are not clear either. Rather, we are offered different versions of a world of overlapping, shifting zones of liberal order, at times confining itself to the Euro-Atlantic, Australasian and Northeast Asian spheres in a world of contention, at others times claiming to have integrated Russia and China into global governance – indeed, creating a unitary ‘global system’ – and a worldwide market economy. The Middle East hardly intrudes, except as a fatal region where American credibility and honour are at stake, and America’s illiberal authoritarian client regimes in that troubled neighbourhood only occasionally enter the stage. The profoundly draconian Saudi bloc, in America’s orbit, is strangely absent in the indictment, as is its array of activities, from imprisoning and torturing feminists, to sponsoring Wahhabist incitement, to practising indiscriminate bombardment in Yemen. We are asked instead to worry about whether the Gulf monarchies find Washington an unreliable patron. Strikingly, the War on Terror – which has persisted for almost two of the seven celebrated decades, which was in itself an attempt to reimpose order, which consumed the lion’s share of the time and energy of the national security state – either goes largely unmentioned, or somehow lies outside the order.

All this ambivalence is partly a matter of many people sharing one tent, as the order appeals to theorists of different strains of theoretical orientation. It is also, though, due to a problem with panegyrics. The genre is primarily intended to affirm, celebrate and warn rather than rigorously establish cause-and-effect, or specify the sequences and weighting of causes. It is also, at root, political. Orders seek legitimacy and credit, while deflecting criticism and blame. The intellectual eulogists of those same orders typically are not writing to make the object of reverence falsifiable. When they do, for instance in the RAND diagnosis, troubling realizations flow that the same order could be complicit in its own undoing:

The order is in the most danger in areas where it has been pushed to the far edges of plausibility. In such areas as liberal interventionism, the reach and extent of European Union bureaucracy, and the speed of global trade integration, the data suggest that overly ambitious efforts to advance liberal elements of the order could be destabilizing.63

Confronted with demonstrable failures beyond (and sometimes within) its own heartland, the rhetoric of order runs up against the difficulty that liberal missions can be self-defeating, and that ambitions should therefore be tempered. Most versions, therefore, do not dwell on such problems, preferring to focus on evil agents, barbaric forces outside the walls or fifth columnists within.

The realization that the world is becoming less hospitable to schemes of visionary world-making, whether due to a relative power shift away from America’s international pre-eminence or a domestic shift away from the orthodox consensus in favour of benign hegemony, has led to an intramural dispute about whether liberal order can outlast the profound changes that are under way. Accounts of the past, present and future of liberal order vary in their judgement about whether the order will survive. Some argue that it is durable and can regenerate through reform, though with increasing unease. Others are more fearful in the age of Trump, and write its obituary with warnings of what is to come. Others stake out a more open ground. Still others suggest that with the superpower abdicating its ‘global leadership’, it falls to other democratic, capitalist states to shoulder the burden and revive the order. As the paramount champion of the progressive middle powers, Germany emerges as the alternative leader of choice, or at least steward and keeper of the flame of liberalism, as the USA lapses into a dark Trumpian age of illiberal barbarism. Germany appears social democratic enough to adopt the programme, and large enough in relative size to count. Its governments, like the leading officials of the EU, appeal to the ideal of rules-based order. So far, this search for a liberal hegemon substitute has not been unduly detained by the possibility that rule-violating Realpolitik also drives the behaviour of Germany and the dominant states within the EU.

Ready for a Master: The Illiberalism of Liberal Order

Paradoxically, liberal order has an illiberal tendency. That is not because its architects secretly intend to do the opposite of what they intend. Rather, it is because liberal expansion is a missionary project that looks to extirpate rival alternatives. Ever since the founding of the USA, the impulses to liberate and to dominate have coexisted. George Washington led the insurgency against the British empire and to the creation of a constitutional republic. He also held slaves and supported the dispossession of indigenous peoples.

As it has been articulated, liberal order demands the perpetuation of American dominance and, effectively, a free hand. In the words of the Princeton Project of 2006, America’s goal should be to secure itself by bringing foreign governments up to PAR, or ‘Popular, Accountable and Rights-Regarding’. Frustrated that legacy institutions are increasingly inadequate to get the job done, the project advocated a loosening of restraints in order-building: ending the veto on UN Security Council resolutions authorizing ‘direct action’ in a crisis, and assuming a responsibility to protect on the part of the international community.64

When visions of a world transformed by a benevolent leader along liberal lines run up against resistance, the responses to dissent are revealing. When gainsaid, the order’s supporting arguments, its intellectual integuments, can turn notably illiberal. The more forceful champions of liberal order treat dissent or revolt with incomprehension. Assuming the obvious rightness of their cause, they regard dissidents not merely as wrong, but as psychologically disordered or morally defective. Rebellion against the order is ‘a pathology to be diagnosed, rather than an argument with which to engage’.65 They insist that ‘if you don’t accept the value of alliances and free trade you are a primitive’.66 Those from the ‘stagnant pool’ of people who want less immigration, we are told, ‘should get out’.67 Those alienated by the evolution of American capitalism have been made ungrateful and decadent by wealth and luxury. They are ‘spoiled’.68 Others dismiss wayward voters as ‘a basket of deplorables’,69 ‘introverted little Englanders’,70 ‘angry old men’ who will soon be ‘freshly in their graves’.71 At its worst, the discourse suggests a classist disdain for flyover country. Former Ambassador to Moscow Michael McFaul says the order’s nemesis, Russian President Vladimir Putin, champions ‘populist, nationalist, conservative ideas’ that are ‘antithetical’ to the liberal order, thereby excommunicating the conservative nationalists who helped create and defend American power.72 Rather than serious self-scrutiny, some of the order’s most outspoken champions explain away a wave of democratic revolts by dismissing millions of people as backward, provincial racists manipulated by diabolical foreign powers. Officials who represent traditional order – like the IMF – congratulate themselves on being ‘the adults in the room’, an old slur that sets established authority and orthodoxy against infantile dissent.73 This leads to the question of how ‘adults’ managed to allow things to get so bad in the first place. These flashes of intolerance, or pity, reflect the ideology’s central tendency. It assumes attraction, but when it encounters resistance or critical fire, it tends towards coercive imposition. Liberalism in any form is supposed to value openness, pluralism and a sense of fallibility. Married to the capabilities of a superpower, it readily becomes a dogma that is jealous, messianic and intolerant, leading to its own illiberal opposite.74

Other advocates of liberal order offer more benevolent sympathy. They too assume that, as the order’s fundamental workings cannot be the root of the problem, people revolt because they are misinformed or irrational. The order is eroding, they fear, not because continued unrivalled dominance is an inherently flawed ambition, but because it has not been properly tried. It needs to be done better. Heterodox elites or disaffected masses have been gripped by bad ideas or bad faith. Or just bad marketing: those who manage the order have poorly sold it. It might need fresh messaging or a ‘reboot’ or an ‘updating’ or ‘renovation’ or even ‘new and urgent conversations’,75 and its defenders should find ‘new ways to articulate their goals to those who feel left behind’.76 The word ‘feel’ is suggestive. Alienation is not because they are left behind. It is a subjective error and a product of false consciousness, according to defenders of liberal order; it is not linked to objective social fact. They commend new programmes to win people over, yet only for ‘preservation and adaptation, not disruption’.77 Problems abroad are attributable to exogenous devils who are malign actors, such as Russia or Iran, whose hostility is rooted in forces unrelated to the order.78 Other primacists find that domestic politics poses the greatest threat to the order, and that for the old order to reproduce itself, it must make a new economic settlement with the American working class, one that does not intrude on the order’s fundamentals. Yet such a settlement would demand some revision of the economic order abroad that has prevailed.79 If some change is needed in order to redress current difficulties, the order’s foundations remain sound and must endure.80 Linked to this mindset is a stark corollary, that there is no alternative model for liberal order in any case, only a regression to inter-war isolationism and/or appeasement.

A principle that worried the creators of the American republic was the damage that a permanent state of war and the creation of overseas empire could do to the republic. That did not preclude violent continental expansion at home or frequent imperialism in its Latin American neighbourhood. Yet, the anxiety that imperialism threatened the republic and that exporting liberty abroad threatened it at home still constituted an important part of the American argument about the extent and nature of commitments, especially beyond its declared Monroe territories.81 A major defect in much of the liberal order literature is that it hardly addresses this historical problem. Rather, proponents of liberal order suggest that the USA can (and often did) domesticate the world according to its own values and virtues. That the planet pushed back, so that the project of world-making actually did more to reorder America than the other way round, hardly upsets the picture. Indeed, recourse to the language and tropes of ‘liberal order’ works as a way of deflecting troubling questions about the relationship between liberalism and imperialism. This deflection ultimately fails, however, as the domestic consequences of a nearpermanent state of war are getting harder to overlook.

For in lamentations about Trump and the end of the liberal era, there is a troubling tendency. Namely, the appeal for a hegemon ordering the planet suggests a most unrepublican desire for a global monarch. And, in turn, this accompanies an uneasy attraction/repulsion to empire and its trappings. Richard Haass, among others, warns of a disastrous American ‘abdication’ of its international responsibilities. ‘Abdicate’ is how monarchs step down. It is no accident that Haass has also called for the USA to become an empire, serving a similar function to that of the British empire.82 Bill Kristol too, who today speaks of a ‘liberal international order’, once argued that ‘we need to err on the side of being strong. And if people want to say we’re an imperial power, fine.’83 The distinction between liberal hegemony, rule by consent, and empire, rule by command, collapses.

Along similar lines, French Atlanticist and war hawk Bernard-Henri Lévy laments America’s supposed ‘abdication’, calls on Washington to recover its ‘liberal vocation’ and ‘moxie’, and deploys overtly regal language in an artful title, The Empire and the Five Kings: America’s Abdication and the Fate of the World (2019). A monarchic and imperial aesthetic can also be seen. The grandeur of the ancien régime attracts Bruce Jackson, founder and president of the US Committee on NATO from 1995 to 2000, who championed NATO expansion and complains of American ‘abdication’ of world leadership, urging Germany to take up the role of ‘enforcing appropriate behaviour in diplomacy’. Jackson expressed hope that his eighteenth-century Bordeaux estate would one day be the site of an international treaty.84 He claimed that ‘someday we’ll write a treaty here on something … And actually, the “Treaty of Les Conseillians” has a nice ring to it.’85

One of the most suggestive manifestos comes from Ivo Daalder and James Lindsay. Their title, The Empty Throne: America’s Abdication of Global Leadership, explicitly invokes a regal account of authority. The front cover depicts an empty chair at the head of a corporate executive table – a most Trumpian image of the world. The underlying presumption is clear. The increasingly disorderly, multipolar world is like a corporation awaiting its CEO to reorder and direct it with its disciplinary hand. Monarchism and commercialism come together. The same authors, like Haass and Lévy, once advocated empire in the pages of the New York Times in May 2003, at the apogee of US unipolar dominance that also marked the point of decline, when ‘empire’ speculation and sympathy for America’s imperial mission were briefly in intellectual fashion, and before ‘liberal order’ returned to replace it as a less provocative euphemism.86 Like many enthusiasts, they exalted empire without looking closely at the process of imperialism. Their argument for American ‘empire’ in 2003 anticipated closely their argument for ‘liberal order’ in 2018. They claimed that, given its ‘power’ and ‘reach’, the USA was an empire, one that was eminently sustainable ‘on the cheap’ (these were early days, before the expenses of ‘global leadership’ became a burden to be solemnly shouldered). They exalted in America’s exceptional and gargantuan capabilities, reminding us that only the USA can float twelve ‘mammoth aircraft carriers’, each housing an ‘air armada larger than the entire air force of most countries’. They pointed keenly to the scale of imperial exertion, with American forces ‘deployed in a grand crescent’ across the Middle East, with American forces bearing ‘absolute authority in Iraq’, which was reassuringly in a state of mere ‘reconstruction’ (again, early days). Having effused grandiloquently over the superpower’s military might, they then reminded Americans that they must exercise a more restrained type of empire, wherein Washington constraints its interests through multilateral institutions, alliances and law. In a nutshell, they want it both ways: the majesty of empire, with awe-inspiring military strength and untrammelled authority in Iraq, and the legitimation conferred by juridical legality and legitimacy of democratic sovereign states, and under an international law that prevails above power.