2

Darkness Visible: World-Ordering in Practice

Think of America’s greatest post-war achievements. Any list would include the transformation of defeated Axis states into proud democracies in Asia and Europe; the containment of the Soviet Union without a major war; the opening up of dialogue with China to assist the Sino-Soviet split, and China’s later entry into international markets; and the termination of the Balkan conflicts of the 1990s. Each triumph was made possible by dark bargains with illiberal forces. To transform defeated Axis powers, and strengthen new regimes, Washington protected surviving elites of the defeated order. It outcompeted the Soviet Union with coups, election meddling, alliances with authoritarians. It avoided major war through the mutual threat of nuclear genocide, and through tacit spheres-of-influence agreements. Dialogue with China, trumpeted in the Shanghai Communiqué in 1972, was purchased at a steep human cost in Bangladesh, outlined in the Blood Telegram. In Asia, wealthy democracies first evolved as protectionist states governed under martial law. The Dayton Accords that terminated the Balkan wars in 1995 locked in tribalism and disenfranchised minorities. Each compromise can be defended. None can usefully be summarized as ‘liberal order’. On the occasions when America did try to create a liberal order, and remake the world in its liberal image, its ambitious projects had inadvertent, illiberal consequences. The struggle for power, against resistance, meant that a hegemony supposed to be marked by rules and regularity instead broke the rules, and dominated through caprice.

An Illiberal World

Ordering involves inconsistency because we live in an illiberal world. The day after 9/11, Prime Minister Tony Blair wrote privately to President George W. Bush: ‘These groups don’t play by liberal rules and we can’t either.’1 Blair’s words reflect an ugly truth. Ordering involves contestation, resistance and suppression. There are actors and interests abroad that do not wish to be ordered, or liberalized, on American terms. In suppressing resistance, hegemons step outside their rules. And because power is limited, hard choices arise that compromise liberal ideals. America defeated each of its main adversaries, from the Axis to the Soviet Union to Islamist terrorist networks, by cooperating with atrocious actors. To prevent dangerous imbalances of hostile power, Washington made common cause with authoritarians. At the height of the Cold War, court historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. reminded National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy that the ‘free world’ led by America included dictatorships in Paraguay, Nicaragua and Spain: ‘Whom are we fooling?’2 Even for well-intentioned rulers, constraints, scarcities and trade-offs create constant struggles between means and ends. Liberal norms are themselves in conflict, between law and justice, sovereignty and human rights, free trade and workers’ protection. A haunting question for US diplomacy is how to promote liberalism abroad. Press for it urgently? Or sacrifice it now for the longer term, hoping that alliance with despotic regimes served the ultimate cause of liberty? Liberal ordering can therefore be taken to mean promoting democracy, accepting it when it emerges, or supporting friendly dictators.3 There is ‘evil in all political action’, warned Hans Morgenthau, so the best we can do is minimal harm.4

Consider the Arab Spring, the wave of revolutions that struck the Middle East from 2010. Washington was torn about how to respond. Lacking a clear compass, by turns it supported, abandoned or toppled dictators. In Saudi Arabia the USA supported its client; in Egypt, it guardedly supported a revolution then helped reinstall a military dictatorship; in Libya, a US-led coalition overthrew a regime by force. Cover-all liberal concepts offered little guide to the choice between the risks of supporting revolutionary change versus sticking by illiberal allies. In an unstable moment in a volatile region, there was no strong-enough ‘vital centre’ with compliant democratic parties that Washington could embrace. As the region erupted, with its epicentre of violence in Syria, the commentariat itself, warning of a ‘post-American’ order, struggled to advise how to translate those principles into action.

Similar problems struck the earlier Bush II administration (2001–9).5 In his second inaugural address, Bush called for Americans to embrace the promotion of global democracy and the end of tyranny as the path to security. This served only to alarm authoritarian Gulf allies. The administration veered between a ‘freedom agenda’ and reassuring its clients of Washington’s support. The militant organization Hamas triumphed against a US-backed Fatah authority in the Palestinian parliamentary elections of January 2006, elections that America encouraged. A realization returned – that the popular will of foreign populations could threaten, not bolster, US interests. Shortly into Bush’s second term, a consensus formed that US interests were too varied, its partnerships with despots too important, to prize liberty over stability.

Order as Hypocrisy

‘Order’ is sometimes spoken of as rule-following, the antithesis of rule-breaking. Double standards, though, lie at the core of ordering.6 To preserve their supremacy and their free hand, rulers will stretch, ignore or reinvent rules at will. Believing they shoulder the burden of serving humanity, and therefore a duty to remain dominant, they will not – when pressed – be bound by deference to the codes they demand of others. One organization that trumpets its rule-oriented quality is the EU. In November 2003, France and Germany flouted the Stability and Growth Pact, the binding agreement between EU member states to help stabilize monetary union, and its rules on the ratio of deficits to GDP. Finance ministers blocked the European Commission’s attempt to fine both states, but the transgression went unpunished, against the Commission’s protests.7

Like EU heavyweights, Washington claims privilege. In February 1998, Secretary of State Madeleine Albright proclaimed: ‘If we have to use force, it is because we are America; we are the indispensable nation. We stand tall and we see further than other countries into the future.’8 For Albright, because of America’s clairvoyance, half a million child deaths under the chokehold of international sanctions were a necessary price for disarming Iraq. Though accusations of mass infanticide were false,9 her calculus was revealing. Washington could take up illiberal means in the service of liberal ends. Luminaries who laud liberal rules, like President of the Council on Foreign Relations Richard Haass, prove to be flexible. Haass urged Washington to treat Russia as a rogue state for violating Westphalian norms of sovereignty. Months later, he called for a US-backed coup in Venezuela.10

To remain in the ascendancy, the USA at critical moments exempts itself from rules and norms, even while preaching them. Consider the history of espionage. The USA has historically been a purveyor of mass, covert surveillance, including against allies. Even in the mythologized moment of creation, at the San Francisco conference that brought the United Nations into being, President Harry Truman had international delegates spied on, clandestinely intercepting their cables.11 Such contradictions echoed through Obama’s final presidential phone call with German Chancellor Angela Merkel in early 2017. They agreed on the need for ‘a rules-based international order’. It was ironic that such affirmation happened by telephone. In 2013, the US National Security Agency (NSA) had tapped Merkel’s mobile phone from a listening post atop the US embassy in Berlin. For Merkel, this was an affront. Germany withdrew from an intelligence-sharing agreement with Washington, denounced the violation of friendship, dispatched envoys to Washington to demand a ‘no spy’ agreement, and initiated a federal investigation. Transatlantic hierarchy reasserted itself, however. The NSA gave scarce cooperation to Germany’s federal prosecutor. Germany judged it better in an hour of international upheaval to ensure intelligence cooperation by being a ‘good ally’.12 The provision or denial of intelligence is part of America’s repertoire. When it did not suit the superpower, something other than ‘rules’ defined the system. Coercion quietly was brought to bear, partly by implicit threat of punishment, and partly by the ally’s internalized realization of the possible consequences. Under the internationalist show, an older power politics endured.

Like great powers before it, the USA demands that its own sovereignty be respected even as it trespasses on that of others.13 America launched coups, including against democratically elected governments (Iran in 1953, Guatemala in 1954, Brazil in 1964, Chile in 1973 – all the way to the democratically elected Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt in 2013), or treated electorally defeated oppositions as legitimate governments-in-waiting, from Palestine to Venezuela. Between 1946 and 2000, America engaged in eighty-one ‘partisan electoral interventions’. In sixteen cases, Washington influenced foreign elections by covertly funding, advising and spreading propaganda for its preferred candidates. Between 1947 and 1989, it attempted seventy-two times to change other countries’ governments. At times, this was done to frustrate land reforms or industry nationalization in other countries. The ordering hegemon allowed itself a different standard, compromising democracy abroad to forge a world safe for its own.

A similar pattern can be seen in the creation of international institutions. The USA helped create the International Criminal Court (ICC) in 1998, but exempted itself from the court’s jurisdiction. The Clinton administration advocated a world criminal court, while striving to limit its writ, ‘to shape a court that would not pose a threat to US citizens’. The State Department declared that it would require immunity from prosecutions, as ‘American armed forces have a unique peacekeeping role’, and, as agents of the superpower, in ‘hotspots’ ‘stand to be uniquely subject to frivolous, nuisance accusations … and [the USA] simply cannot be expected to expose [its] people to those sorts of risks’.14 Washington strong-armed and bribed other states into Article 98 bilateral agreements, to commit not to extradite US citizens.15 In August 2002, the American Service-Members’ Protection Act (ASPA) was introduced, banning military aid to countries that ratified the Rome Statute, the treaty that established the ICC, and placing sanctions on countries that failed to sign Article 98 agreements conferring immunity on US citizens. The coercion was explicit. In the case of aidseeking Lesotho, a ‘blunt’ meeting with the US Ambassador indicated that Lesotho’s profile as a non-signatory nation jeopardized its prospects of receiving aid.16 The ASPA also authorized military force to free US nationals detained by the ICC, and became known as the Hague Invasion Act. Amongst the ‘yea’ votes passing the act were Democrat champions of liberal order: Senators John Kerry, Hillary Clinton and Joseph Biden. To uphold order, the superpower sought immunity from the ICC, reserving the right literally to attack its institutions.

A Warrant to Strike

The problem of making and breaking rules becomes more intense with regard to the use of force. It resurfaced in September 2013, in debates over whether to conduct punitive airstrikes against Syria for its murderous use of chemical weapons. British Prime Minister David Cameron’s government talked emphatically about a rules-based international system. Against the threat of a Russian veto, however, Cameron discovered reasons to set rules aside. To insist on a UNSC resolution for military action would be ‘contracting out our foreign policy, our morality, to the potential of a Russian veto’,17 a ‘misguided approach’. Some countries, this implied, were entitled to unilaterally suspend rules for the greater good. This pointed to a conflict within international order. An unauthorized attack on Syria, as some observed, ‘might uphold the norm of CW non-use, but it would surely undermine the norm against interstate uses of force without UN Security Council authorization except in cases of self-defence’.18 Would Cameron support non-Atlantic powers if they exercised the same discretion, to uphold a humanitarian norm by violating a rule? If not, he thereby claims a privilege, revealing that rules are not paramount.

Not all practitioners of order go to the trouble of developing a theoretical basis for rule-exemption. Former Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter, who invoked a ‘rules-based order’,19 a decade earlier joined with former Secretary of Defense William J. Perry to advocate bombing North Korea’s nuclear weapons programme to disrupt Pyongyang’s ballistic missile tests ‘before mortal threats to US security could develop’.20 This went beyond a prudential ‘pre-emption’ option. A stationary North Korean nuclear-tipped missile, without other indications of aggression, would not in itself constitute evidence of an imminent threat and would not permit ‘anticipatory self-defence’ under international law. They were arguing for preventive strikes, to destroy a more distant threat, an illegal act of aggression based on the Caroline case of 1837 and under the United Nations Charter. Without spelling it out, Carter and Perry asserted a privilege, permitting the superpower to discard rules to neutralize an unacceptable threat. They would hardly allow other sovereign states, including North Korea, to exercise that prerogative. The sheriff retains a warrant to strike at will.

Frustrated by veto players in the multilateral forums whose creation they celebrate, traditionalists seek to create alternative doctrines and institutions to authorize the hegemon’s actions. In the Princeton Project she co-convened with John Ikenberry, Anne-Marie Slaughter, sometime Director of Policy Planning in the State Department, argued for ‘A World of Liberty under Law’.21 Yet in two cases where Washington applied force without seeking a mandate from the UNSC, against Serbia in 1999 and Iraq in 2003, Slaughter discovered a rationale for benign vigilantism, a doctrine she described as ‘illegal but legitimate’,22 finding that ‘insisting on formal legality in this case may be counterproductive’, though later she lambasted the Bush II administration for rejecting treaties, and flouting rules and the norms of global governance. In the case of Serbia, her doctrine invested NATO, a collective security system, with the authority to supplant that of the UN. In the case of Iraq, she hoped legitimacy would derive from success, replacing process with conquest as the determinant. We have, then, a doctrine of expediency that improvises a basis for rule-relaxation. The Princeton Project proposed the creation of a concert of democracies as ‘an alternative forum for liberal democracies to authorize collective action, including the use of force, by a supermajority vote’. If the international system will not confer legitimacy or enable action, the superpower should not submit itself, but instead invent other seats of authority, and new rules. When institutions threaten to block American action, those in favour of unauthorized action develop alternative rationales, go ‘forum shopping’, or simply press ahead, advocating implicitly for a privilege without explaining.

That does not mean Washington cares little for international institutions. To the contrary, it invests effort in their maintenance and functioning. Institutions and rules serve a purpose, not to constrain but to legitimize the hegemon’s preferences. The pattern of post-war practice was that other states sought to bind the USA to institutions, that the USA mostly agreed with reservations, but then refused to be bound behaviourally. When they played any role at all, institutions were ‘used by US policymakers to project and enhance the unilateral exercise of American power’.23 Washington repeatedly went against those institutions that supposedly checked its power as it acted unilaterally, from the repudiation of the International Trade Organization Treaty in 1947 to the adoption of a flexible response nuclear posture to the termination of the Bretton Woods financial system.

International order, then, is not ‘based’ on rules. Like a spider’s web, it is strong enough to catch the weak, yet too weak to catch the strong. Rules exist but do not define the system. Powerful states adhere to them only when they serve their self-defined interests at acceptable costs.24 The fact that, in March 2019, there were fifteen cases before the ICC, and all the accused were African, points to de facto great power immunity. By contrast, ‘when American staff sergeant Robert Bales allegedly shot dead sixteen civilians in Afghanistan, including nine children, he was quietly spirited away to a military prison in the US, despite the demands of Afghan President Hamid Karzai to try him in the country where the massacre took place’.25 Every major power has significantly violated international law, rejected the rulings of international courts, or denied their authority. President Jacques Chirac’s France, like Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder’s Germany, opposed the invasion of Iraq in the name of upholding UNSC authority. Yet France flouted the same rule, participating in NATO’s unauthorized bombing of Serbia in 1999 to rescue Kosovo Albanians from genocide. In 1985, following the sinking of Greenpeace’s Rainbow Warrior by two French secret agents, the French government agreed to allow an arbitration process but refused to submit evidence to the ICC. In the 1980s, when Nicaragua successfully sued America before the International Court of Justice (ICJ) over the mining of its harbours, Washington refused to pay reparations or recognize the court’s authority. America’s then UN ambassador Jeane Kirkpatrick pronounced accurately that the ICJ is a ‘semi-legal’ body that ‘nations sometimes accept and sometimes don’t’.26 The world’s emerging counterpower, China, shows a similar attitude. In the summer of 2016, it defied the unanimous ruling of the Permanent Court of Arbitration that found against its territorial claims, continuing to seize disputed waters, islands and shoals in the South China Sea. Washington appealed to China to respect the ‘legally binding’ verdict, yet had not ratified the convention it urged China to observe.

Great powers, then, transgress rules with impunity. Faced with this simple truth, liberal order proponents respond with intellectual gymnastics. Some reply that at least offending states offer public legal justifications for their actions, reflecting the order’s normative power.27 Since such gestures are mostly costless rhetorical ones, that consolation is weak tea. Others offer protective clauses: ‘Liberal international order is built around open and at least loosely rule-based relations … general principles and arrangements, as opposed to those built around regional blocs, spheres of influence or imperial zones.’28 If rules are only ‘loosely’ the basis for relations, then great powers can abandon them at will – and they do. Others apply easier tests, looking to formal and official behaviour as a metric of the liberal order’s health. For instance, one RAND study uses the frequency of the passage of UN Security Council resolutions as a measure.29 This neglects incidents of the ‘closet veto’, whereby permanent members privately threaten use of the blocking prerogative to limit the UNSC’s agenda and kill off unfavourable resolutions, preventing discussion of taboo issues. Thanks to hidden veto threats, the UNSC never debated the Algerian war or the partitioning of India, failed to classify the Rwandan atrocities as a genocide, and declined to name Vietnam, Afghanistan or Chechnya as armed conflicts. Others just lower the bar, claiming ‘rules-based’ just means ‘whether the norms affect state and state actors’ behaviours’.30 But many things affect state behaviour apart from rules, such as greed, or the desire to maximize power. If rules only apply sporadically among other variables, then the system cannot be ‘based’ on them. To assimilate the disagreeable fact of great power rule-violation, the claim of rules-based order needs so many caveats that it dissolves in a sea of qualifications.

The Order at Birth

At the moment of its creation, the order was not intended to work along the lines for which it is now revered. Multilateral institutions were meant to legitimize hierarchy in a negotiated universe of major powers, without constraining its most determined acts. For the Roosevelt administration, as it created new international architecture, the new system would lock in the privilege of the four great powers – the USA, the UK, the Soviet Union and China – while offering a sop to smaller states to feel included. For Roosevelt, the Big Four would make ‘all the more important decisions’, the United Nations working as a safety valve to let small countries ‘blow off steam’.31 And nor would the ruling quartet be equals. Roosevelt presumed a relatively weak China, and an Anglo-Soviet standoff in Europe.32 The founding state intended the UN to bolster American primacy, reconciling the principle of universal participation with the reality of great power control. It would appeal to international organizations when convenient, and bypass them when necessary.

During the Second World War, voices within the US government, such as Secretary of State Cordell Hull, argued for a ‘stable and enduring’ order, which would prevent regression to ‘economic conflict, social insecurity, and again war’.33 Yet the desired pathway to these goals differed significantly. American power was to make that world through coldly calculated coercion, as well as attraction. Assistant Secretary of State Dean Acheson’s wartime accusation against the Treasury Department exaggerated a basic truth about US war aims, ‘a victory where both enemies and allies were prostrate – enemies by military action, allies by bankruptcy’.34 During wartime, America created economic instruments to weaken the economic sinews of British international power. Sentimentality and blood ties only went so far. Asserting itself as the new colossus, Washington dismantled Britain’s imperial preference trading arrangements and the supremacy of the pound, which was supplanted by the dollar as the key international currency. It attached not a heavy interest rate, but heavy conditions to its post-war loans. It went back on wartime commitments, forcing Britain to drop import controls and accept currency convertibility, and withheld promised nuclear-sharing arrangements. America had two aims in mind: to weaken and take receivership of an exhausted British empire, while keeping it strong enough to endure as a supportive satellite. The net result, after Britain’s wartime sacrifices, was to turn it into a subordinate power and a financial supplicant.

A defining episode was the Suez crisis of 1956. In that hinge event of the Anglo-American relationship, the US Sixth Fleet stalked and harassed British ships in the Mediterranean, fouling their radar and sonar, menacing them with aircraft and lighting them up at night with searchlights. With the pound and oil supplies under pressure, President Dwight Eisenhower coerced Britain with the formula of ‘no ceasefire: no loans’. Patronage could be rapidly withdrawn, regardless of recent history, blood ties or shared visions of order. Rules, norms, values, institutions – the new liberal order – did not prevent Britain from trying to maintain a colonial possession. And it did not stop the USA from arbitrating the matter by targeting its ally’s vitals.

The post-war world before the term ‘liberal order’ came into being was a foreign country. If there were general principles that underpinned the UN at its founding, they were at first self-determination and sovereignty, selectively applied, rather than democracy and human rights. Recall that two of the permanent five of the UNSC were totalitarian communist states. Two of the democracies held colonial empires. The USA itself covertly assisted France in its campaign in Indochina (1946–54) and its colonial order in Asia. A major feature of the post-war order was the Cold War, the long security competition with the Soviet Union, which gave a particular shape to the calculation of ends and means. We can observe the interplay of sameness and difference in the rhetoric of order, then and now, in the Clifford Memorandum of 1946.35 It bridged the earlier Long Telegram by George Kennan of September 1946 and the later guiding template NSC 68 of 1950, as a consensus formed for anti-Soviet containment. The Memorandum spoke of a ‘decent world order’. Yet in contrast to recent statements about liberal order, the memorandum advocated preparation for biological war – outlawed by the 1925 Geneva Protocol – as, along with nuclear weapons, it ‘may be the only powerful deterrent to Soviet aggressive action’. Roosevelt had already authorized a secret biological weapons programme that would last decades. The Memorandum cautioned against arms control measures, as ‘proposals on outlawing atomic warfare and long-range offensive weapons would greatly limited the United States strength’. And it de-emphasized direct military commitments, prioritizing favourable trade agreements, loans and technical missions to demonstrate capitalism’s strengths. Evidently, attitudes to what lay within or beyond the bounds of liberal order, what instruments were optimal, legitimate or taboo, were historically unstable.

The order also took root in America’s handling of defeated adversaries, whom it looked to remake as subordinate allies. Important in the literature are the ‘bargains’ between the USA and the states it garrisoned and rebuilt: West Germany and Japan. Those bargains involved compromises with the old orders, whose help the USA sought. West Germany, like NATO, retained officials who had been security elites in the Third Reich. Former Nazi mandarins stuffed the highest levels of government. Several former Nazi generals would later become senior commanders in the Bundeswehr. By suppressing the record of their complicity in war crimes, the USA helped former Nazi scientists, engineers and technicians to emigrate, to assist its ballistic missile, aerospace and other weapons programmes.36

In Japan, the creation of a new order involved the exoneration of an emperor complicit in war crimes. To bolster the post-war settlement through the Showa throne as ‘symbol monarchy’, in 1946 General Douglas MacArthur’s staff helped Emperor Hirohito rewrite the history of his reign and shift blame, exculpating him of responsibility for his country’s disastrous imperial onslaught that had killed more than twenty-three million people, reinventing him from meddling ruler to blameless ceremonial monarch. Carefully managed war crimes trials wrote out the Emperor’s complicity in arms expansion, militarism, emperor-centred nationalism, and his destabilization of the party cabinet system.37 Japan could be remade into an anti-communist bulwark, then coerced into signing a bilateral treaty with Taiwan in 1952 and conceding a US presence in Okinawa and the Bonin Islands.

Similar predicaments confronted US diplomats again decades later, as they oversaw the reconstruction of states after shooting wars were terminated, such as the Balkan nations after the bloodlettings of 1992–5. To purchase an end to fighting, the Dayton Accords locked in ethnic divisions and partition. The insistence on democratization within the framework of the status quo meant that the main group affiliations (Bosnian, Serb or Croat, corresponding to confessional affiliations) dictated the distribution of government posts, institutionalizing divisions in the new constitution. Ethnic cleansing was effectively rewarded with the creation of Srpska. With the predominant groupings entrenched, seventeen of the country’s officially recognized minority groups were prohibited from running for high office. The choice was a painful one between two illiberal poisons, either a settlement organized around a presumption of separate ethnic groups rather than transcendent individual citizenship, or continued killing, with the prospect of defeat for the Serbs. An illiberal world constrained even the superpower, as it brokered peace.

Political Economy

As the USA rose to international pre-eminence, it strived to reshape the international economic environment, to establish and exploit the dollar as the reserve currency, to open markets on its own terms, to make a world safe for the penetration of American capital. How far did that process, that longstanding commitment to the ‘Open Door’, represent a liberal drive for free trade? According to admirers, a great deal. Not only was a commitment to free trade allegedly a core component of the US order; it also holds out a general lesson, that free trade leads to peace and prosperity, while protectionism drives war and poverty. At times, proponents point to China’s entry into the WTO, and the global economy, as a major dividend. The practical inference is that the USA ought to expand free trade, eschew protection and join rather than reject free-trading compacts such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

As we will see, the notion that America rose to power through a post-war political economy of unfettered capitalism on a level playing field is in fact ahistorical. Note, though, that this false memory played a central part in the way a triumphant America treated post-Soviet Russia. After communist rule collapsed in 1991, at the urging of and pressure from the US government, Moscow embarked on a programme of ‘shock therapy’, to restructure Russia around the principle of market exchange, adopting accelerated privatization of state industries, deregulation, fiscal discipline and the shedding of price controls.38 This experiment was a major effort in the project to enlarge the order at a rapid pace. It had the support of the leading institutions of global capitalism: the IMF, World Bank, and US Treasury Department. Harvard academic Jeffrey Sachs, one of Russian liberalization’s architects from 1991 to 1993, set out the programme’s logic: ‘To clean up the shambles left by communist mismanagement, Eastern Europe must take a swift, dramatic leap to private ownership and a market system.’39 ‘Swift, dramatic leap’ – a vast programme grounded in classical liberal economics took on the tempo and zeal of the revolutionary communism it aimed to replace. These rapid reforms replaced an oppressive and failed communist system. They did so at the continual insistence of Washington that Russia must reform itself on ‘our conditions’. The results on many measures were disastrous: capital flight and deep recession, slumping industrial production, malnutrition, a criminalized economy, a corrupt oligarchy enjoying a concentration of wealth, and the decline of health care and an increased rate of premature deaths.40 By eschewing the more gradualist path of Poland or China, the consequences were profoundly illiberal.41 ‘Liberal order’ visionaries are quick to give their ideas credit for the prosperity of nations from Western Europe to the Pacific Rim, finding causation in correlation. They deny such a direct link between their ideas and the problems of post-Soviet Russia.42 Yet it is hard to accept that measures like sudden privatization and the rise of monopolies in a corrupt country were not related to asset stripping and capital flight, or that eliminating housing and utilities subsidies that millions of poor families relied upon did not play a major part in the social ruin that followed. Western technocrats, diplomats and politicians were deeply implicated in the new order’s design.

What about the earlier history of political economy? Historically, great powers do not become great powers via free trade.43 Countries tend to preach the doctrine of free trade only after becoming economically dominant. Ascending powers typically rise through the deliberate intervening hand of an activist state. They tend to shield their infant industries with bans, tariffs and other controls, while imitating or stealing innovations and technology abroad. This applied to Britain in the eighteenth century, and it applied to the USA of the nineteenth century, which had grown through a mercantilist policy under Founding Father Alexander Hamilton. It also applied to post-war America. The USA resolutely imposed restrictive measures when it suited, with non-tariff protectionism a persistent feature of US policy. A range of instruments was fashioned to restrict trade: bilateral voluntary export restriction agreements, orderly marketing agreements, quotas, buy-American requirements, export subsidies and discriminatory product standards. Allies and clients also practised protection, including the prosperous Asian states of Taiwan and South Korea after the Second World War, as well as the more democratic (but tightly supervised) Hong Kong and Singapore. One major pillar of the post-war order was Japan, which instituted, ‘the most restrictive foreign trade and foreign-exchange control system ever devised by a major free nation’.44 South Korea evolved first as a dictatorship under authoritarian founding fathers Syngman Rhee and Park Chung Hee, who nurtured under state protection the chaebol business groups, Hyundai, Daewoo and Samsung. Free markets only emerged from initially highly protected markets. The EU today insists that poor external countries drop tariffs and capital controls, even while it maintains extensive agricultural subsidies.

China occupies a central place in the debate over liberal order. Defenders of the order credit it with facilitating China’s entry into capitalism, thereby driving international growth. China’s model, though, is tightly controlled state capitalism. It is a notorious economic ‘cheat’. Beijing maintains a non-level playing field that advantages state-owned enterprises.45 It flouts WTO rules. It steals intellectual property and practises cybertheft. It forces foreign firms to share technology and banks to partner with local firms. China never accepted open markets, controlling investment and the movement of funds. Beijing achieved rapid industrial revolution through authoritarian measures. These included forced resettlement and urbanization schemes, population control through forced abortion and compulsory sterilization, severe working conditions, repression of civil society including trade unions, labour and human rights activists, and internet surveillance.

Foreign farmers would be baffled by the claim that the old order embodied free trade, when the USA was set on granting agricultural subsidies and other mechanisms that limited foreign governments’ access to US consumers. Consider the lavish subsidies for American agriculture, both overproducing and then at times dumping produce on world markets. Efforts within Washington to liberalize American trade practices met the veto-wielding resistance of the US Committee on Foreign Investment. Euphemisms eased the path. Mercantilism was renamed ‘industry policy’ or ‘strategic trade policy’. The post-war trading order, institutionalized first in the GATT and then in the WTO, saw a decline in tariffs that was offset by an increase in non-tariff barriers.46

The trading relationship between the USA and Australia offers a revealing snapshot of the economic order. The USA, the EU and other major agricultural producers like Japan practised farm protectionism to such an extent that Australia regarded it as a betrayal of wartime solidarity and sacrifices. In particular, America’s Farm Bill and the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy are at odds with the principles of international trade liberalism. Politically effective farm lobbies ensured that subsidies and restrictions remained strong. In 1955, the USA insisted on a ‘temporary’ waiver from GATT rules on import restrictions, threatening to leave if it didn’t get its way. The waiver was indeed temporary, staying in force for almost forty years. The USA restricted imports of sugar, peanuts and dairy products until 1993. Affected nations created the Cairns Group of Fair Trading Nations in 1986 to advocate the liberalization of agricultural produce. Australia’s foreign minister branded wheat and cattle subsidies ‘the act of a hostile power’.47 When Australian farmers advocated closing joint defence facilities, US Secretary of State George Shultz advised Australia not to link agricultural policy with defence hosting. The issue threatened to boil over when President George H. W. Bush visited a recession-blighted Australia in January 1992. Bush acknowledged that trade disputes collaterally damaged Australian farmers. Yet subsidies continued. Exercising its ‘voice opportunities’, Australia was met with polite silence.

In reality, there were several post-war economic orders.

Globalization on a large scale, characterized by the emergence of transnational corporations and supply chains, got underway only in the 1990s and 2000s. Mass immigration to the United States and Europe is also largely a post–Cold War phenomenon. The euro and the Eurozone date back only to 1999. Labour mobility within Europe is also a relatively recent policy. Controversial ‘megaregional’ trade pacts like NAFTA, the TPP and TTIP [Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership], which go beyond old-fashioned tariff reductions to rewrite much domestic legislation, go back only to the 1990s.48

Earlier decades saw restrictions on the mobility of finance, with capital controls, fixed exchange rates and periodic returns to tariff barriers. The long competition with the Soviet Union moved the USA to deliberately encourage the economic growth of its Asian allies, but under the shield of a neo-mercantilist state that also brought patron and client into periodic conflict. Nostalgists wrongly historicize and seek to naturalize what is in fact a recent set of post-1989 international arrangements.

America remains a ‘long-term and prolific proponent of protectionist policies’.49 Since the 2008 financial crisis, the country has imposed tariffs worth $39 billion, while the world’s top sixty economies have adopted more than seven thousand protectionist trade measures, worth more than $400 billion. The USA and the EU both held the highest number of protectionist measures, each exercising more than one thousand, with India at a distant third at four hundred.50 America’s trade protectionism has the highest impact on other countries.

The reversion to protectionism had precedents before the global financial crisis. Some of the most strident advocates of open markets and the dismantling of trade barriers have in practice done the opposite. One was President Ronald Reagan. Reagan championed the cause of free trade as a foundation of progress and peace. As president, he increased the proportion of imports subject to restrictions by 100 per cent from 1980, as well as tightened quotas, voluntary restraint agreements, new duties and raised tariffs, and he strengthened the Export-Import Bank, in order to protect the recovery of US industries, especially the auto, computer-chip and the steel industries. Reagan justified these steps as forcing economic competitors to trade freely. President Bill Clinton also championed free trade, in words and deeds, driving through NAFTA, a free trade zone in North America, and pushed for China’s admission to the WTO under ‘most favoured nation’ status. Yet under Clinton, rice subsidies that continued during his administration enabled US growers to dump their product onto the markets of vulnerable rural countries in Haiti, Ghana and Indonesia at depressed prices.

President George W. Bush emulated Reagan rhetorically, invoking the principles of free trade and unfettered markets. Yet in 2002 he increased steel tariffs by 30 per cent only to back down twenty months later under threat of punitive counter-tariffs by the EU. Confronted with the prospect of economic meltdown in the crisis of 2008, Bush intervened in the market with strongly protectionist measures, including bailouts of major firms, claiming: ‘I have abandoned free-market principles to save the free-market system.’51 The reintroduction of protectionist measures today, then, is not such a sudden or radical departure as is sometimes claimed. America’s continual contortions on the issue reflect the inherent difficulty of liberal projects, whose architects often feel impelled to compromise with illiberal pressures. A world where even the most avowed exponents of free trade continually return to protectionism when markets exert their pressures is not the flat capitalist world we are being invited to be nostalgic for.

A Nuclear Order

The world after 1945 was also shaped by the nuclear revolution. For the first time, humanity developed a weapon that could inflict instantaneous devastation on large populations and urban centres, and could do so without first achieving military dominance over its target. Thus, the instrument was radical for its disproportionality to most strategic goals, the extreme difficulty of defending against it and its ‘equalizing’ capacity, whereby even a relatively weak possessor could inflict a dying sting on an adversary so severe that the damage would exceed the value of the object being fought for. Mutual deterrence became the main foundation for the avoidance of major war. Most pioneered in the USA, the weapon also became an international innovation. It spread to other major powers, often against Washington’s wishes. And to its credit, the USA went to considerable lengths in collaboration with post-Soviet Russia to prevent the disastrous spread of nuclear materials, through the Nunn–Lugar Cooperative Threat Reduction Program, which dismantled WMD – weapons of mass destruction – arsenals in the former Soviet Union. Like mutual deterrence, successful arms control was a collective process. It relied for its success on pragmatic cooperation with illiberal states.

This nuclear reality made the post-war order less violent than it might have been, at least at the highest level of calculations about major war, even if nuclear weapons can also destabilize interactions at lower levels. The capacity of nuclear states to exercise deterrence via threat of punishment, holding at risk what adversaries value, was broadly restraining. To presume otherwise, that nuclear weapons were irrelevant to the absence of major war, is implausible. It would be, as Michael Quinlan writes, to hold that

Western possession of nuclear weapons could have had no impact upon the Soviet Union’s assessment … of its options in relation to West Berlin, which it could always have overrun swiftly by non-nuclear force. It has to hold that Pakistan’s possession of nuclear weapons makes no valid contribution to its sense of security in face of India’s superiority at other levels of military force. It has to hold that if governments implacably opposed to Israel’s existence came widely to power among its neighbours and successfully made military cause in aggression, they could and would feel confident that Israel would accept political obliteration by conventional or Chemical Weapons force rather than exercise the nuclear-weapon option … it has to hold that at the time of the 1990–1 Gulf War, Israel’s known albeit undeclared nuclear capability not only did not play but also could not have played any part in Saddam Hussein’s decision not to use Chemical Weapons against Israel as an assured means of fracturing the country’s patience, and so of triggering the Israeli intervention which he deeply desired to engineer in order to split the coalition against him.52

The arrival of nuclear weapons, their increasing range, followed by even more powerful thermonuclear ones, was a bleak new reality. It did not correspond with the values of liberalism. With their invention and the technology attached to them now permanent and ineradicable elements of the species’ future, the achievement of peace and stability between major powers rested on a brutal calculus, of threatening genocide to prevent genocide. It effectively and permanently conscripted the civilian populations of those states, forcibly making them the targets of potential apocalyptic exchange. In the USA, this led to a major concentration of power in the executive branch, effectively a ‘nuclear monarchy’.

To create the conditions for creative world-making, the USA first swept aside its chief Asian competitor. The same president celebrated for founding the liberal order, Harry Truman, also launched two atomic strikes on Imperial Japan in August 1945, immolating and irradiating two of its cities after a campaign of blockade, firebombing and starvation. He did so to sweep aside a competitor that had been brutally pursuing a rival vision for an Asian order of its own. Washington thereby introduced a genocidal weapon into the world. There are powerful arguments that this was the ‘least bad’ choice available. Tellingly, though, in panegyrics for a dying liberalism, the words ‘Hiroshima’ and ‘Nagasaki’ hardly appear. Similarly, primacists today speak of America’s historical creation of a free and open Pacific and of US-led globalization as a peaceful project, but rarely mention the bloody point of origin, when Commodore William Perry forced an isolated Japan into a commercial treaty at gunpoint. Typically, orders are birthed in creative destruction, whether in the form of gunboat diplomacy or atomic terror.

Nuclear weapons and the threat of their use barely appear at all in panegyrics, except in admirable, peaceful efforts to prevent or slow their spread, such as through alliances or the Non-Proliferation Treaty (1970). But even these best case examples involve darker elements. The NPT regime is a classic instance of great power privilege in action, committing the possessor states to eventual, negotiated disarmament, while in practice Russia and the USA modernize and refresh their arsenals, reaffirming the central importance of nuclear weapons in their doctrine. Five NATO non-nuclear weapons states have also defied the cause of disarmament, volunteering to act as surrogate nuclear states by equipping their forces to deliver US nuclear weapons in wartime.

Proponents of liberal order attribute the absence of major war to American hegemony. In the avoidance of Armageddon, though, also important is the fact that enemies of the US-led order constrained the USA with the threat of annihilation, making the eruption of a third world war less likely. Since it takes at least two sides to make a war, the absence of major war was a co-creation between Washington and its nuclear-armed, totalitarian rivals. That deterrence helped constrain the USA is suggested by the fact that it went to great lengths, with mixed success, to inhibit the spread of nuclear weapons and develop counterforce capabilities to overcome the logic of mutually assured destruction, precisely because it wished not to be deterred.53

We should also be wary of triumphalist claims about the prevention of major war. The shadow of major war never went away, and indeed helped to define the period. The relationship between nuclear weapons, stability and deterrence is a complex one.54 Threats of nuclear retaliation can both induce caution and create new sources of instability. Nuclear possession both constrains and, under some circumstances and at lower levels of conflict, emboldens. The possession of nuclear weapons may limit competition at the upper end of the violence scale, but it does not eliminate competition outright. Moreover, either side may seek bargaining advantages in manipulating the risk of escalation in games of ‘chicken’. And either side may have different ideas of where the sub-nuclear threshold lies, creating the possibility of misperception and misapprehension.

If the nuclear order helped the world in the period of the Pax Americana avoid a major war, it was a near-run thing. There was a series of high-stakes near misses, caused by fear, misperception, false alarms or system errors.55 In 1962, the Joint Chiefs of Staff pressed the Kennedy administration to attack Cuba, not knowing that Soviet combat forces possessed nuclear-tipped missiles and were authorized to use them, and a Soviet submarine commander who believed the war had started had to be dissuaded by fellow officers from firing a nuclear torpedo. At other moments, warning systems misidentified the moon, a flock of geese and military exercises as nuclear attacks. Between the Soviet Union and the USA, the deterrence relationship was at times unstable, with the reciprocal fear of surprise attack. If the pursuit of stable deterrence dictated that security could be achieved through mutual vulnerability, both sides at times refused to concede their own vulnerability, and competed for war-fighting advantage. A set of unstable interactions grew, through arms competitions and technological development, through a fear of having an inferior nuclear arsenal and through a fear that one’s assured capacity to retaliate was threatened. To their credit, the USA and its principal opponent went to great lengths eventually to stabilize the relationship.

Thus, the boast that a liberal order prevented major war is complacent. The sources of mutual survival lay partly beyond the good deeds of a liberally minded hegemon, through a deterrence relationship that depended on others’ restraining force, and organized around weapons that cannot by definition be used liberally. At times, that relationship was dangerously unstable and the threat of nuclear war came close to being a reality. Summaries of this history as ‘peace and prosperity’ under one power’s supervision are glib, to say the least.

Spheres of Influence

According to the reigning orthodoxy, the creation of spheres of influence is antithetical to US-led world order. The clash over Ukraine in 2013–14 restaged the question. As America, its allies and Russia clashed over the status of the Ukraine, European diplomats insisted that the EU ‘doesn’t do geopolitics’.56 European leaders, likewise, defined their visions of order against what they see as an atavistic form of politics. As Angela Merkel put it, ‘We thought we had left all that behind us.’57

This is ahistorical. In the USA and the EU, the historical record shows a back-and-forth between declaratory, Wilsonian traditions of self-determination and de facto claims for their own spheres. The EU’s offer to Ukraine in 2013 of a trading Association Agreement, with Washington’s backing, constituted an attempt to enlarge a Euro-Atlantic sphere, both commercial and military. The Agreement contained clauses tying Ukraine to Western military and security policy, committing Ukraine to ‘promote gradual convergence in the area of foreign and security policy with the aim of Ukraine’s everdeeper involvement in the European security area’. It provides for ‘increasing the participation of Ukraine in EU-led civilian and military crisis management operations’ and exploring the potential of militarytechnological cooperation.58 Whatever the intent, Russia perceived the process as expansion against its vital interests. EU enlargement with the promise of an extended security perimeter looked to Moscow like geopolitics and an advancing sphere. This was especially so given the wider context of the Bucharest Declaration promise of eventual NATO enlargement into Ukraine and Georgia. Russian security elites feared Western expansion would dangerously convert a buffer state, and a historically vital territory, into a hostile client state, bringing potential adversaries into further proximity. In particular, Moscow feared losing its naval base in Sevastopol and its ability to project power in the Black Sea and the Mediterranean.59 A reactive Putin improvised with subterfuge and armed proxies, and bit off the Crimea. After a US-backed protest movement – the Maidan revolution – forcibly overthrew the pro-Russian government in Kiev, Putin then supported a sustained insurgency in Ukraine against the new, Westward-leaning government. Assumptions that Russia must realize the West’s benign motives, or that the EU does not ‘do geopolitics’, left Western officials shocked at Moscow’s retaliation.

Traditionalists may resist the claim that this counts as a sphere, countering that it was merely the offer of a voluntary integration, allowing a country to enter a prosperous zone of democratic capitalism. Spheres do not have to be imposed, however. Cuba’s attempt to join and enlarge the Soviet sphere, after the revolution of 1959, was encouraged but not imposed by Moscow, just as NATO was created partly by the demand of European states as an ‘empire by invitation’. And although it does not always admit it, Washington itself insists on a sphere of influence. It does so in Latin America and its Western hemisphere, where it intervened militarily in 1965 in the Dominican Republic, in Grenada (1983) and Panama (1988), and in 1994–5 in Haiti. US leaders looked on sympathetically as its ally, France, repeatedly intervened in its former colonial territories in Africa. It maintains, too, a historical prohibition against outside powers interceding in its sphere. If, say, Mexico or Canada were to test this sphere by hosting Chinese or Russian military forces, or joining the Shanghai Cooperation Council, or if another great power formed alliances in the Caribbean, the USA would not react as though ‘spheres of influence’ were illegitimate. This is reaffirmed by the fact that hawkish primacists who exercise influence in US government explicitly insist on American exclusivity in its own hemisphere. Jealous of a Russian presence in Venezuela, National Security Advisor John Bolton affirmed that ‘the Monroe Doctrine is alive and well’, refusing to rule out the ‘Roosevelt Corollary’ of US military intervention.60

In the wake of 9/11, the USA effectively claimed the world as its sphere. Since terrorists could now strike from anywhere, the superpower arrogated to itself a ‘hunter’s licence’. This was the prerogative of pursuing, capturing or killing them, without regard for sovereignty if necessary, with ‘the right to dispense with all the restraints of international law’.61 With its self-awarded free hand abroad, the USA adopted expansive war powers, resorted to covert ‘black sites’, renditions of suspects without trial, and an ongoing campaign of extrajudicial assassinations, at times without the consent of host countries. After a UN special rapporteur suggested in 2013 that the Obama administration’s drone bombings were possibly illegal, the White House boycotted inquiries of the UN Human Rights Council.62 Creative legal bases for such action could be found. Pakistan, a site of frequent drone attacks, never formally consented to them and officially opposed them. It cleared airspace for drones and left them unmolested, for fear of retaliation. Washington interpreted its passivity as consent. A practice of ‘coerced consent’ arose, probably illegal.63 The wording of the 9/11 Commission effectively declared that the real estate of American primacy was infinite. As globalization had shrunk the distinction between terrorism ‘over there’ and ‘over here’, ‘the American homeland is the planet’.64 Washington could kill from the sky at its own discretion.

America’s claim to an exclusive, planetary sphere reflected the imbalance of power of unipolarity. At other times, to prevent unwanted conflicts, Washington willingly entertained the proposition of mutually tolerant spheres. At the order’s birth, Presidents Roosevelt and Truman in practice, and in private, in turn accepted the principle. Roosevelt’s Four Powers would ‘police’ their respective domains. The Yalta and Potsdam summits in 1945 recognized de facto spheres while publicly denouncing the principle, just as the USA accepted the ‘percentages agreement’ over Eastern European states negotiated by Churchill and Stalin in Moscow in October 1944. The Red Army’s presence in conquered territories made division a fact, which could only be overturned by going to war. After earlier belligerent warnings, the USA at Potsdam in July 1945 became passive in the face of Soviet broken promises about free elections in occupied Eastern Europe. By late 1945, the US government was no longer interested in the internal politics of Poland, coming to accept it ‘in fact, if not in word, as an integral part of the Soviet sphere of influence’. In practice, the entire region had by December 1945 been accepted as an area where the Soviets ‘would run the show’.65 Secretary of State James Byrnes expected the Soviets to accept that Western powers would hold sway in the vital areas of Western Europe, Japan, the Mediterranean and the Middle East, in exchange for acceptance of Soviet dominance in Eastern Europe. All this was at odds with the Wilsonian tradition and American formal statements, so ‘for that reason, a certain amount of discretion was always necessary’. The new president, Harry Truman, believed that a negotiated pulling apart would be necessary to avoid collision. As he conceded, and as was noted by Secretary of Defense James Forrestal, ‘We shall have a Slav Europe for a long time to come. I don’t think it is so bad.’66 This private remark was later deleted from Forrestal’s published diaries.

The notion of spheres of influence was accepted by a number of presidents during the course of the Cold War. At a meeting in Paris on 4 June 1961, President John F. Kennedy expressed hope for a territorial settlement with Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, saying that the US government did not ‘wish to act in a way that would deprive the Soviet Union of its ties to Eastern Europe’, in exchange for the status quo in a divided Berlin, a statement that was then deleted from the declassified version of the document.67 In an interview with the Soviet newspaper Izvestia in January 1962, Kennedy indicated that as the USA had not intervened in Hungary in the 1956 uprising, it should have a free hand in Cuba. This principle emerged from dangerous test cases, from the suppression of revolt in Hungary that the USA had initially supported in 1956, to the naval blockade of Cuba where the Soviet Union was installing medium-range ballistic missiles in 1962. From these episodes, stable mutual expectations formed. Other Cold War US presidents intervened more subversively in the Soviet orbit, only then to pull back and accept that it was more prudent if not to recognize spheres, at least to tolerate them by limiting interference. This was the case for Dwight Eisenhower after the crushing of the Hungary uprising in 1956 and Ronald Reagan during and after the Polish uprising of 1982. For much of the Cold War, Washington tacitly accepted the Soviet sphere in Eastern Europe just as the Soviets did in reverse in the Caribbean, at least to the extent of mutual restraints on excessive interference beyond the mutual propaganda war. The concept was used effectively to de-escalate tensions. The signing of the Helsinki Final Act in 1975 had mixed results, but it effectively recognized a Soviet predominance in Eastern Europe. The principle of parity guided periodic returns to détente between the superpowers.

None of this precluded proxy competition in other battlegrounds. Those in favour of the situation view the major military conflicts of the post-war period largely as sideshows, footnoted as the ‘weaker, less developed and peripheral states’,68 separate acts that can be set aside from the overall story. This is a problem, because the order exerted and defined itself just as much in the shadows and at the outer edges. To preserve or advance order, the USA projected itself deliberately and forcefully into the weaker, less developed areas so as to shape the system as a whole. It is to war itself that we now turn.

Wars for Peace

Orders are warlike things. Even pacification for the common good involves much fighting. An increase in power made the USA more prone to military activity. The first two decades of the unipolar Pax Americana after 1989, which made up less than 10 per cent of America’s history, generated 25 per cent of the nation’s total time in armed conflict. That period is more bellicose by an order of magnitude than the preceding eras of bipolarity and multipolarity, in terms of frequency if not intensity.69 Likewise, while the USA launched 46 military interventions during the Cold War, that number jumped to 188 in the 1992–2017 period. Those who defend hegemony do not deny the existence of fighting. But they do claim that their order is less lethal than the chaos they hold at bay. Defenders of the Pax Americana contend that their order should be judged by history’s standard. The US world order is more benign than those of the Romans, Mongols, Ottomans, Europeans, Nazis, Japanese or Soviets. The issue, however, is not whether the Pax Americana was more liberal than its predecessors – it clearly was – but whether calling it ‘liberal’ adequately describes its working, and whether in fact it works. For America’s busy and bellicose recent decades have not been an era of foreign policy triumph. The issue is increasingly urgent. For the republic to be secure, must it achieve unchallengeable armed supremacy and sole leadership over the earth?

Liberal order visions have an uneasy relationship with war and ‘hard power’. Its proponents do not deny, in fact they affirm, that the American superpower upheld peace partly through preponderance, or overwhelming military strength and its wise deployment. However, they emphasize the non-bloody uses of force and its pacifying and democratizing effects. Uses of force appear, albeit in largely clinical terms. In the foreground, American military pre-eminence deterred adversaries, reassured and united allies, dampened spirals of alarm, and prevented conflict. This makes them most at home, intellectually, in continental Europe, the strongest case study for highlighting the consensual, attractive quality of American hegemony. The actual exercise of force, the process of war and the threat of it, retreats to the background. As one account claims:

The system established after 1945 was built on US power. But it endured and, after the end of the cold war, expanded because US leadership was embedded in multilateral rules and institutions. Everyone had a stake. Washington sometimes over-reached – in Vietnam or with the invasion of Iraq. By history’s standards, however, the Pax Americana was essentially benign, resting as much on the force of example as military might.70

Such rhetoric, suggesting a benign essence, brushes off disastrous and lengthy wars as episodic lapses, distances hegemony from violence and rule-breaking, deflects scrutiny and sidelines the exercise of military power that was a major aspect of world-ordering.

Some credit the USA with creating an unprecedented level of relative peace across the world. But these optimistic assessments exaggerate the decline in war. They measure the amount of war by counting the dead. As Tanisha Fazal has shown, this is misleading, as it overlooks one of the most fundamental changes in modern war, that societies are better at keeping injured combatants alive.71 A significant shift during the life of the Pax Americana was the advancement of battlefield medicine, which dramatically shifted killed-to-wounded ratios. Wars that once upon a time would meet the minimum threshold for inclusion in datasets are now omitted. The difference in counting method alters the estimate of war’s incidence dramatically. Exclusive focus on battle fatalities suggests a 50 per cent decrease in the incidence of armed conflict since 1946. Once non-fatal casualties are priced into the equation, that reduction falls to less than 20 per cent, a less statistically significant trend. Especially now, it is wrong to conflate war’s frequency with its lethality. A narrow focus on counting the dead leads, in turn, to a neglect of the costs of war for itself, given the large number of physically and psychically wounded survivors, and the deaths that injuries can lead to, only later and far from the front.

The USA successfully reduced levels of strife in other ways, though not through mechanisms of liberal order. Consider one of the most far-reaching post-war diplomatic breakthroughs that made Asia more peaceful: the settlement between President Nixon and Chairman Mao in 1972. Mao agreed to cease sponsoring revolutions against American interests throughout the region, effectively acknowledging America’s primacy in Asia and reducing threats to US interests. In return, the USA formally recognized communist China, one of the world’s most internally repressive states. It agreed to the ‘one China’ policy, a blow to the cause of Taiwanese independence. In fact, Nixon agreed to sacrifice Taiwan later as an unimportant commitment. It abandoned Tibet’s independence movement. The rapprochement with China was set up via a secret channel to the country’s leadership through an intermediary, Pakistani President Yahya Khan. In turn, Washington kept Khan’s cooperative back channel open by maintaining a strict silence during the cancellation of a free election and the Bangladesh genocide of 1971, despite the pleas of the US ambassador’s ‘Blood Telegram’, which documented the slaughter that killed hundreds of thousands and displaced millions. America purchased détente with a totalitarian regime at a heavy price.72

These Realpolitik bargains are different from the more ambitious claim, that US dominance suppressed the belligerence of others through its preponderance of power, the protection and reassurance it provided, the deterrence it exercised and the general promotion of humanitarian norms. Some of this is true for Northern zones like Europe, many of whose states under NATO’s protective umbrella consciously created an anti-militarist culture. The ‘peaceful’ Northern states, though, enjoy peace locally while still being implicated in large-scale violence elsewhere. They export violence to the more war-torn Southern states in other ways: through a lucrative trade in arms and expertise, by supporting and arming proxies in civil wars, and through use of standoff methods such as airstrikes that transfer the burden of risk onto faraway civilian populations. Counter-arguments, that this overall reduces more than enlarges the totality of violence by strengthening client states or suppressing terrorist organizations, still involve a calculus of illiberal means for liberal ends.

Unprecedented levels of peace do not describe the experience of large parts of Africa. Even by history’s bleak standards, Africa’s multisided ‘great war’ in and through the Democratic Republic of Congo between 1998 and 2001 was an abnormal spike in concentrated violence, inflicting a total of between two and five million deaths in five years.73 Neither can this be regarded as a separate, indigenous struggle, given Western states’ involvement in the militarization of Africa, the large economy in arms transfers and military training. The US government claimed that such programmes were intended to promote order, by enhancing peacekeeping and professionalism. ‘Whatever their intention’, the World Policy Institute found in 2000, ‘skills and equipment provided by the US have strengthened the military capabilities of combatants involved in some of Africa’s most violent and intractable conflicts.’74 Given the extent to which Western development of other countries is emphasized, it is hard to exclude these elements from the order’s history.

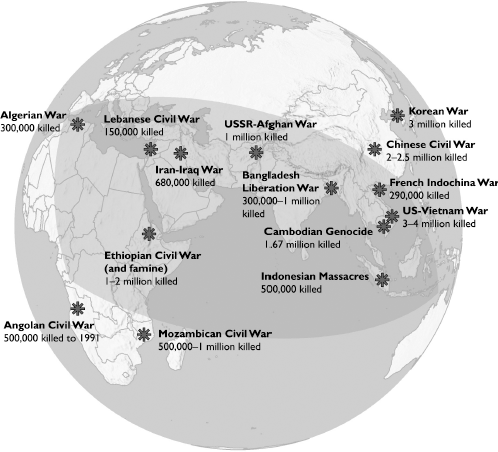

The history of liberal order is summarized as being one of relative tranquillity and abundance. The ‘world order’, it is asserted, ‘worked for most of the world, delivering stability, prosperity and peace. There have been violent conflicts at the peripheries, but only rarely between major powers.’75 The map shown in Figure 2 demonstrates that the periphery was wide and bloody.76

The post-war order featured intense wars, especially in Asia. Including a large theatre of war spanning the ‘rimland’, or southern Asia, from the Middle East and Central Asia to the Manchurian Plain and Indochina, perhaps fourteen million perished in armed conflicts since 1945.77 To treat this belt of territory, these bloodlands, as a minority and peripheral concern is not only complacent, over-privileging continental Europe and Northeast Asia; it wrongly positions those conflicts as sideshows. In fact, major powers exported money, guns and their own intrigues and firepower to the peripheries in order to shape core interests. Therefore, the deaths and maiming of millions were part of the act of ordering, intended to shape the balance of power in the world’s designated ‘core’.

Containment of communism, and the counter-attempt to break out of the containing ring, was a brutal affair. To defend authoritarian regimes from ruthless communist adversaries, the USA waged wars that laid waste to large parts of the Korean peninsula and, later, Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos. The Korean War (1950–3) was a devastating conflict. At a conservative estimate, the US military killed one million Koreans, civilians and soldiers and 400,000 Chinese combatants.78 For Washington, aligned with the ‘volatile, autocratic’ President Syngman Rhee of South Korea, at stake was America’s reputation. Korea was ‘a symbol [of the] strength and determination of [the] West’, especially for ‘countries adjacent to [the] Soviet orbit’.79 As for Vietnam (1965–72), estimates of casualties are approximately one million communist combatants and 365,000 civilians. US firepower/punishment strategies and mass bombardment did not inflict all the casualties, of course; their opponents were also brutal and determined. But given the tonnage of ordnance dropped, and other measures such as the thirteen million gallons of Agent Orange chemical defoliant, the Americans must still have inflicted a sizeable share. That war spread also to Laos and Cambodia in bombardment to interdict reinforcements and supply, with casualties inflicted by US bombing conservatively estimated at 200,000, including 100,000 killed, while displacing approximately two million souls.

Figure 2 Superpower-fuelled conflicts of the Cold War in the Eastern hemisphere and the quadrilateral in which George Orwell predicted the war’s battles would take place.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Daniel Immerwahr, with information drawn from Paul Chamberlin, The Cold War’s Killing Fields: Rethinking the Long Peace (New York: Harper Collins, 2018); Alex de Waal and Bridget Conley-Zilkic, Mass Atrocity Endings, at https://sites.tufts.edu/atrocityendings/; Bethany Lacina and Nils Petter Gleditsch, ‘Monitoring Trends in Global Combat: A New Dataset of Battle Deaths’, European Journal of Population 21:2–3 (2005), pp. 145–166.

Vietnam is central to the argument. That war was one of the most significant attempts at world-ordering undertaken by an American government. The architects of the conflict sincerely believed it was a necessary act in protecting the US-led free world.80 In the crucial 1964–5 internal debate about the escalation of US ground commitment to support the South Vietnamese regime, planners inside the Johnson administration were aware that prevailing over communist insurgents in Vietnam would be complex and difficult.81 They believed the campaign was still worth it, to uphold many of the same imperatives espoused by believers of today’s liberal order, to prevent destabilizing chain reactions from undermining the alliance and commercial system. Hostile political waves, they feared, could become tsunamis that could undermine the free world, if not as regional dominoes, then as global revolutionary waves. If the USA failed to project credible resolve to an ally on the periphery, then it would undermine the faith of allies in Europe and Asia, leading potentially to West Germany or Japan hedging or defecting to the Soviet sphere. Holding the line in Vietnam would buy time and breathing space for American allies and clients to shore up their defences. According to presidential advisor John McNaughton in a memo of 25 March 1965, US policy in Indochina was ‘70% – To avoid a humiliating defeat (to our reputation as a guarantor)/20% – To keep South Vietnam (and the adjacent territory) from Chinese hands/10% – To permit the people of South Vietnam to enjoy a better, freer way of life.’82

The doctrine of ‘credibility’, in which the integrity of America’s alliance system rested on its international stature, defined how the domino doctrine was conceived. Similar fears animated President John Kennedy, who in November 1961 feared that negotiating over Vietnam would trigger a ‘major crisis of nerve’ throughout Southeast Asia. The Rusk–McNamara report of that month warned that the loss of Vietnam would ‘undermine the credibility of American commitments elsewhere’. Later apologias for the Vietnam commitment, by National Security Advisors Walt Rostow and McGeorge Bundy, maintained that it prevented wider regional domino effects, buying time for Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) states to grow their economies. In 1969, National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger reasoned that at stake in Vietnam was ‘confidence in American promises. However fashionable it is to ridicule the terms “credibility” or “prestige”, they are not empty phrases; other nations can gear their actions to ours only if they can count on our steadiness.’83 The tonnage of US bombing in Vietnam was triple that of the Second World War. Concentration of such violence in one theatre, the rationale went, would limit its spread into others. They hoped illiberal means, or unremitting bombardment and secrecy, would serve ultimately liberal ends, the defeat of totalitarian communism.

The Iraq war, too, was an effort to reorder the world. Its makers aimed to spread capitalist democracy on their terms, and to demonstrate strength. In 1997, a group of hawkish intellectuals, the Project for a New American Century (PNAC), had urged the USA to ‘accept responsibility for America’s unique role in preserving and extending an international order’,84 and adopt ‘military strength and moral clarity’, urging President Bill Clinton to remove the despot Saddam Hussein from power. They got their way in 2003. A longstanding duel with a defiant regime in the Persian Gulf finally came to a head. The US-led invasion of Iraq in March 2003, its architects hoped, would not only remove a growing perceived threat, a rogue regime in Baghdad and its arsenal of dangerous weapons; it would enhance international order, in different but complementary ways.85 The 9/11 terrorist attacks, like earlier security crises, prompted a renewed push for transformational war. If ordering involves the attempt at creation out of the wreckage of destruction, policymakers sensed such an occasion from the slaughter of civilians on American soil on 9/11. Emboldened by apparent success in Afghanistan, and on the back of a decade of successful minor wars, policymakers sensed a world-historical drama. ‘Let us reorder the world’, declared British Prime Minister Tony Blair in October 2001, a call that resonated in the USA. President George W. Bush identified an ‘opportunity to achieve big goals’, leading to ‘world peace’. National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice argued that ‘this period is analogous to 1945 to 1947’, an occasion to define and recast world order as the tectonic plates of world politics shifted.86 If Afghanistan was not enough, overthrowing Saddam Hussein’s regime in Baghdad was a necessary further measure, going beyond the arid hinterlands of Central Asia and driving on to the more strategically consequential, oil-rich Greater Middle East. Toppling Saddam Hussein’s tyrannical Ba’ath regime would be a decisive step in regional transformation like the large-scale, mid-twentieth-century projects of transforming defeated states into beacons of liberty. As one official remarked, ‘the road to the entire Middle East goes through Baghdad’.87

Advocates of invading Iraq conceived it as a ‘world-ordering’ war in two distinct respects, one romantically idealist, one a hard-nosed form of power-seeking. For hawkish liberal internationalists, it was a bid to reorder the region positively, on moral and strategic grounds: ‘to liberate the Iraqi people from their dungeon’ and to establish ‘a beachhead of Arab democracy’, for ‘Iraq as a secular democracy with equal rights for all of its citizens’.88 Toppling one rogue regime at the heart of the Middle East would begin a benign domino wave of reform. A Pentagon paper of 2003 suggested that, given Iraq’s ‘size, capabilities and resources’, becoming a democracy would exert ‘historic’ impact ‘in the region and the world’.89 Paul Wolfowitz, hawkish democratic idealist, in late November 2001 oversaw the influential advisory paper ‘Delta of Terrorism’, the clandestine manifesto of a group of intellectuals, which anticipated a two-generation war with radical Islam, calling for regime change in Iraq to begin the transformation of the Middle East out of ‘malignancy’, to reverse the ‘stagnation’ that produced ‘radicalism and breeds terrorism’.90 For the more narrowly nationalistic, the war would send a powerful signal of American resolve to competitors and allies alike, restoring generalized deterrence after the 9/11 attacks revealed the superpower’s vulnerability. A prison-yard rationale took hold, that the USA should from time to time throttle a weak country, to demonstrate its steel. This found advocates from Vice-President Dick Cheney to former foreign secretary Henry Kissinger, to columnist Thomas Friedman. The presumptions that came with power, that the USA has a unique, hegemonic purpose to remake regions, created a dangerous confidence. ‘Iraq can’t resist us’, one enthusiast declared.91