30 FRAGRANT HARBOR

FRAGRANT HARBOR

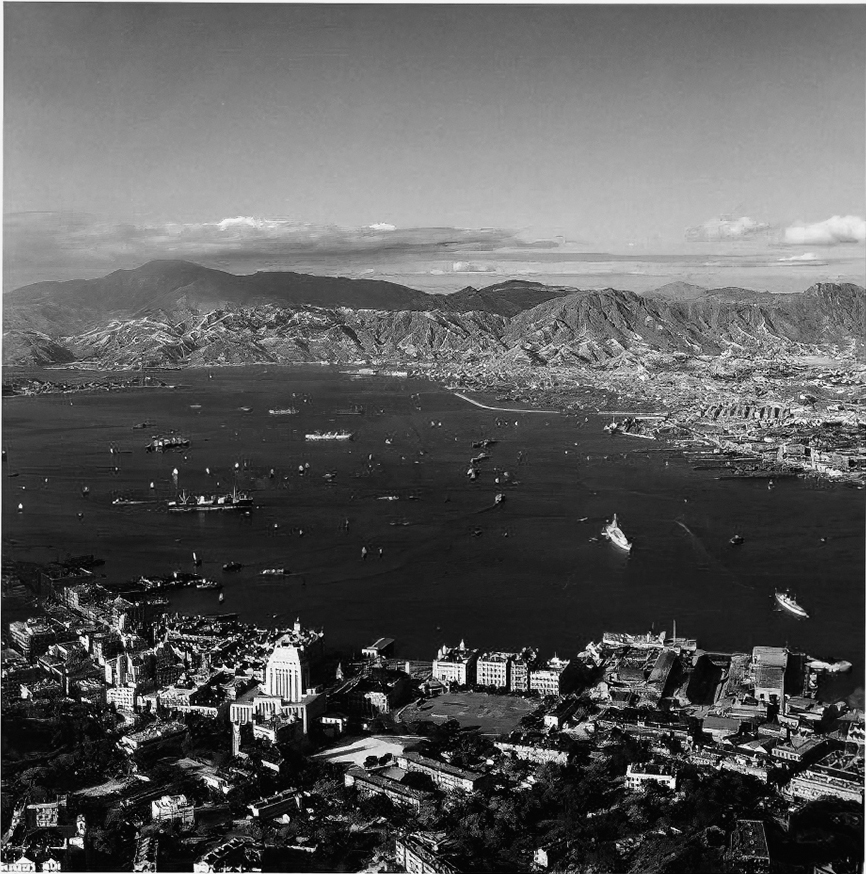

Victoria Harbor, Hong Kong, circa 1940s (Courtesy of Hedda Morrison Collection, Harvard-Yenching Library of Harvard College Library, Harvard University)

SOME YEARS EARLIER, while basking in the afterglow of her captivating performance in The Thief of Bagdad, Anna May would often sing a melancholic ballad that someone had written for her at a Hollywood house party:

I’m Anna May Wong

I come from Old Hong Kong

But now I’m a Hollywood star

I’m very glad

Dream in the nap, Bagdad1

And now, after ten days in Shanghai, Anna May sailed for the Chinese city that rhymes with her family name. Originally, Hong Kong was going to be her first destination on this China trip, for she was eager to cross the border to visit her ancestral village outside Canton, where her father and siblings had been living for more than two years. But Shanghai, agog with the thrill of having a movie star in their presence, had planned so many events in her honor that Madame Koo and her brother begged her for a longer layover, to which she acceded.

On February 21, 1936, after a bumpy passage on the SS President Grant through the rough and nippy waters of the East China Sea, Anna May arrived in Hong Kong. Literally meaning “Fragrant Harbor” in Chinese, Hong Kong had been no more than a cluster of fishing villages on the fringes of the Qing empire when it first appeared on the global stage in 1842. After its humiliating defeat in the First Opium War (1839–42), China ceded the island to Britain for 150 years, a concession that infuriated Lord Palmerston. Belittling the island as a barren rock that would “never be a mart of trade,” the bellicose foreign minister sacked the entire negotiating team. History, however, proved Lord Palmerston’s shortsightedness. By 1936, after about a century of British colonial rule, Hong Kong had metamorphosed into an international city with a population close to one million. A vast emporium of commerce with a veneer of lacquered wealth, it stood at the crossroads of East and West, a crown jewel on the British imperial map, even though life on the island was a bit—shall we say—stale, thanks to the rigidity of colonial rule. Compared to fast-paced Shanghai, where competing forces of governance bred vitality as well as chaos, Hong Kong suffered from the parochial and restricting snobbery of the ruling British elites, addicted as they were to precedence and protocol. It made Hong Kong, pleasant as it was, more or less a colonial backwater, an impression confirmed by Anna May upon her arrival.

“Hong Kong is a lovely place for its cleanliness, healthiness, and order,” she said. “Shanghai, on the other hand, is a place of activity, or shall I say, hectivity.”2 From the ship’s deck, she saw a bustling harbor crammed with sampans, skiffs, and Chinese junks. The lush green Victoria Peak (better known as The Peak), dotted with white mansions where wealthy Europeans luxuriated in the panoramic view and temperate climate to the exclusion of Chinese, loomed in a misty haze. To the north, the blue hills of Kowloon rose like ramparts guarding a city with an invisible army. To the west and south, the ocean’s bald rocks evoked bobbing sea turtles. Anna May once again recalled scenes from The Toll of the Sea, with its story set in Hong Kong. In the far distance, the dim coast of the Chinese mainland curved like a fading eyebrow of an ancient empress dowager.

Walking down the gangplank a little wet from the drizzle, Anna May wore a crimson coat, a black hat with a veil, and a gray fox-fur stole around her shoulders. Stepping onto the wharf, she was so overjoyed to see her sister Lulu, her old friend Moon Kwan, and the welcoming party they had brought, that she totally forgot to greet the quayside mob of journalists and fans. It was later announced that her apparent aloofness was caused in part by the fact that she had caught a cold crossing the East China Sea and was exhausted from the journey. Public sentiments could be fickle. Among those who felt slighted on the wharf were the representatives from the Association of the Taishan District, where her ancestral village, Chang On, was located. Founded on the bedrock of patriarchal order, filial piety, and inviolable rules for propriety, such an organization would often consider any small deviation or affrontery as serious as disturbing the equilibrium of the universe, the Way of Heaven. As a result, the welcome scene turned vengeful, as some members of the delegation yelled at her, screaming, “Don’t let her go ashore!” She then rushed to the Hong Kong Hotel, the city’s first luxury hotel, which had opened in 1868 and faced the waterfront on Queen’s Road.3

The next morning, Anna May was upset by the headlines in the local Chinese papers. They faulted her for having given the press “the cold shoulder” and called her interpretations of Chinese in her films “an insult to Chinese people.” To remedy the situation, she invited the journalists to her hotel room for an interview. Fighting off flu symptoms, she held court for hours, patiently answering questions and addressing topics that ranged all the way from the modern Chinese woman and Lady Precious Stream to Hollywood’s ongoing Shakespearean fad and the state of world cinema. “The modern Chinese woman,” she said, “seems to be holding her own with the outside world. She is giving the world a chance to get acquainted with her. The older generation always stayed at home and the Chinese woman was a person of mystery except to her family or immediate friends.” Having compared the old and new images of the Chinese woman, she explained her own part in shaping some of the stereotypes, insisting that “she was not responsible for the interpretation of Chinese roles in American films as these parts were given to her by the directors. She had no say in the matter.”4

When words failed to change minds, Anna May turned to fashion to soften her image. On the day before her departure from Shanghai, she had done a session with Tsang Tsing-ying, a China Press artist, who made sketches of the actress in her various haute-couture dresses from Paris, London, New York, and Hollywood. Now these sketches appeared in the paper, creating quite a stir in Shanghai and Hong Kong—two centers of modern Chinese fashion. The dresses featured in the sketches, accompanied by brief remarks and captions, included a gown specially designed by the famous Hollywood designer Howard Greer, which was made of gold lamé with a train that could be converted into either a cape or a sari; a printed satin tunic blouse over a black satin skirt, and a black mandarin-style coat to match; a black broadtail three-quarter coat, cut straight with slits on both sides and buttoned almost all the way down; and a “calla dress,” a tunic of white satin over a pleated skirt with sleeves cut to resemble the calla lily. All of these designer dresses showed a combination of Oriental and Parisian influences.5 Quite soon, when her back-alley Shanghai tailor finished her orders, she would have even more new clothes with which to show the world her impeccable taste and creative ideas.

Even her improved reputation in the Chinese media, however, could not undo the damage caused by Anna May’s unintentional slight of the Taishan welcoming committee, whose members sent a cable to her father, urging him not to allow her to visit Chang On. If she insisted on coming, they warned, “The entire family might be expelled.” It seemed that her long-awaited “homecoming” would have to wait a bit longer.6

Meanwhile, as in Shanghai, Hong Kong’s social elites opened their arms to embrace the Hollywood star. Peter Sin, an influential lawyer who sat on the boards of several charity organizations, hosted a lavish reception at the Peninsula Hotel. The venue, a colonial-style establishment founded in 1928 by the Kadoorie family, was a favorite meeting place for the local elites. Sin had made Anna May’s acquaintance four years earlier in London, where he had become the first Chinese barrister permitted to practice in Britain.7 Also attending the reception were US Consul General Charles Hoover, Moon Kwan and his colleagues from the Grand View Sound Film Company, and other dignitaries and parvenus.

The next day, Sin accompanied Anna May and Lulu to visit Sir Robert Ho-tung Bosman at his private residence on The Peak. Known as “the grand old man of Hong Kong,” Bosman was the son of a Chinese woman and Mozes Hartog Bosman, a Dutch Jewish tycoon who had made his fortune in the Chinese coolie trade. Having built an empire in shipping and real estate in the colony, the wealthy Bosmans were the Rockefellers of Hong Kong. Ho-tung’s maternal half-brother, Kom-tong, had a harem of twelve wives, countless mistresses, and reportedly more than thirty children. One member of the brood was Grace Ho, born of his British-Chinese mistress in Shanghai. Defying her family by marrying a poor Cantonese opera singer, Grace would sever her connections with the Bosmans and tour America with an opera troupe. On November 27, 1940, between curtain calls in San Francisco, Grace would give birth to a boy she named Bruce Lee. Thus, unknown to most, the man who would become the icon of Asian masculinity and introduce the word kung fu to the English language turned out to be a circumcised Jew. Bruce Lee, the great-grandson of Mozes Bosman, was five-eighths Chinese, one-quarter English, and one-eighth Jewish.8

Though Eurasian, Ho-tung identified himself as Chinese, a choice clearly reflected in his sartorial preferences. Educated locally at Queen’s College, Ho-tung inherited his family’s commercial empire and became the richest man in Hong Kong by the age of thirty-five. His private residence on the lush hills of The Peak consisted of several buildings named Ho-tung Gardens. Prior to the opening of the Peak Tram in 1888, the residents of the exclusive Peak area were carried up and down the steep slope on sedan chairs. According to a city ordinance, and in a decree reminiscent of South African apartheid, no Chinese were permitted to live on The Peak, and Chinese servants of white residents were given passes to enter the “holy land.” Visiting the area in the spring of 1936, Emily Hahn was struck by the rank discrimination, as she wrote in her China memoir: “Only one Chinese, an old fellow named Sir Robert Ho-tung … was permitted past these magic if imaginary portals. Sir Robert was too rich to ignore, so the British allowed him to build his house on his own Peak land, and to live there when he wanted to.”9

Around five in the afternoon, just as the sun dipped over the edges of the Western Hills, Anna May, clad in a black Western dress under a fur coat, arrived at the Ho-tung Gardens with her entourage. The Grand Old Man lived by himself in a separate house called the Neuk, but he entertained guests at the gardens, where he had received the US vice president a few months earlier. At seventy-three, he was in great health, with a back straight as a rod and a gait like a young man’s—he would live until his mid-nineties. Above his Chinese robe was a long, bony face, sculpted like ancient Greek art and fine-lined like a map of Asia. Over the delicacies provided to accompany afternoon tea, Anna May chatted with the host in Cantonese, mixed with English when necessary or convenient—her native Taishanese being slightly different from the Cantonese spoken in Hong Kong. She told him about her trip thus far, her wish to cross the border to see her aging father, and her plan to study Chinese opera in Peking. Ho-tung nodded approvingly, impressed by the chiseled beauty and unusual résumé of the laundryman’s daughter.10

Later that evening, Cao Shanyun, a prominent esquire, invited Anna May to attend the races in Happy Valley. The racecourse was another popular venue for local elites and ordinary citizens alike; even the Shanghai-based tycoon Sir Victor Sassoon kept some of his prized thoroughbreds in a stable there, and he would often bring his female guests, such as Emily Hahn, down to Hong Kong to watch the races. Anna May did not find Sir Victor and his entourage at the crowded tracks that night, but she was introduced to Hong Kong Governor Sir Andrew Caldecott. With the unique distinction of having the shortest tenure of governorship (1935–1937) in Hong Kong colonial history, Sir Andrew was a stickler for rules that perpetuated class divisions. He became notorious for explaining in excruciating detail whether Britons of various ranks visiting the colony should make their presence known by signing the visitors’ log in the embassy or Government House: “Heads of Department must, their deputies should, other officers of more than ten years seniority might.… Members of the Legislature must, Town Councilors should, heads of mercantile houses and persons authorized to sign for them ‘per pro,’ might.… All others might not.”11 With a prig like that, Anna May could not do much except exchange some polite pleasantries, as if scripted by a bored screenwriter.

Still waiting for the misunderstanding with the Taishan Association to sort itself out so that she could visit her father, she decided to take a break from Hong Kong’s unseasonable cold and seek sunshine elsewhere. Coincidentally, arriving in the colony on March 12 with his fiancée, Paulette Goddard, was Charlie Chaplin, who also complained about the coldness of Hong Kong.12

On March 2, 1936, Anna May left for Manila on the SS President Polk. As she told a friend afterward, she went to Manila for sunshine and rest but got only the sunshine.13 She tried to enter the Philippines incognito to avoid attention, but word spread fast on the street. It was not long before she was spotted, and a platoon of reporters then trailed her everywhere. In consolation, she not only enjoyed excursions into the beautiful countryside outside Manila but also was treated royally by the social elites in the newly established Commonwealth. Since the Spanish-American War of 1898, the Philippines had been an American territory, which lasted until 1934, when Congress passed the Tydings-McDuffie Act, granting independence to the islands after a ten-year transition period. In 1935, a constitution was written and the Commonwealth of the Philippines was established. Manuel Quezon, son of a Chinese mestizo, was elected president. The inauguration ceremony, held in November 1935 and attended by a US congressional delegation led by Vice President John Nance Garner, drew a crowd of around three hundred thousand.

Now, less than four months into his presidency and still savoring his landslide victory in the election, President and Madame Quezon invited the visiting Hollywood personage to dinner at the Malacañang Palace. Afterward, there was a party for Anna May, attended by Nicasio Osmeña (son of Vice President Sergio Osmeña) and the two Elizalde brothers, Joaquin and Manolo, who virtually owned the entire country through their sprawling business empire. Anna May was having a glorious time, except that, between the Elizalde brothers and young Osmeña, she did not have a spare moment to herself.14

After a busy week in the Philippines, she returned to Hong Kong aboard the President Pierce, docking on March 9. To her delight, she found a package waiting for her—her photographs taken by Carl Van Vechten back in New York. She was flattered to see the glamorous portraits, many saturated in a voyeuristic intrigue, by an amateur but renowned photographer who would, unknown to her at that moment, become an important part of her legacy in popular culture. Even more exciting was the news that she would finally be allowed to visit her father in China. She and Lulu immediately stepped on the Kowloon-Canton Express, carrying enough candy and red envelopes for the entire village.15

As the train rolled through the rural landscape of the Pearl River Delta, Anna May saw vast fields dotted with mist-shrouded hamlets. The tableaux included dim profiles of peasants in bat-wing straw capes driving water buffalo at a pace slower than time, and an endless esplanade of dwarf palms waving their green leaves as if welcoming her home. Standing at the southern edge of the Middle Kingdom, this region had historically borne the brunt of China’s disastrous clashes with Western powers. It was here that the first salvo of the Opium War was launched. This was also the birthplace of Dr. Sun Yat-sen, who came of age in Hawaii and returned to China to lead a revolution to overthrow the Manchus. And here was also where the real Charlie Chan, Chang Apana, the bullwhip-wielding Honolulu cop-turned-movie-icon, had grown up. Even the world-renowned Siamese Twins, Chang and Eng Bunker, could find their roots here, their father having been a Cantonese fisherman who had migrated to Siam.

As the source of the earliest waves of the Chinese diaspora, this area was the spiritual home for overseas Chinese. Old people would come back here to die; failing that, they asked that their bones be sent back here for burial. Anna May recalled the passengers crowding the belly of the President Hoover crossing the Pacific, the looks of longing on their faces during their homebound journey. She finally understood why her father, having worked and lived in America all his life, was so eager to return to the land of his ancestors. It was a land under a spell.

Disembarking at her destination, she found Canton to be the most Chinese city she had visited. Shanghai was too international to be called China, and Hong Kong was a British colony in name and in appearance. Anna May and Lulu, however, had no time to sightsee in Canton, the first Chinese port open to the world. They got into a car headed for Taishan, the county seat, and from there they trekked the three-mile muddy country road to Chang On, where their father was waiting.

For this China trip, Anna May had made an arrangement not only with Randolph Hearst’s New York Herald Tribune to write a series of articles, but also with Hearst Metrotone News to make a documentary film to be broadcast later. As a result, Newsreel Wong, Hearst’s man in China, was there to film the family reunion in the rustic village.

As she reached the end of the dirt path between rice paddies with her younger brother Richard, Anna May was greeted by her father. She had never seen him so happy. Surrounded now by his offspring from the two worlds that were once a galaxy apart, he displayed a wide grin on his wizened face. While The Good Earth, embodying America’s cinematic imagination of China, was being shot in the California desert, Newsreel Wong’s camera was capturing a slice of Chinese life that was as real as the soil on which they stood. Although the former Los Angeles laundryman’s story might not have been as epic as peasant Wang’s saga under Pearl Buck’s pen, Anna May felt ecstatic walking into the camera’s frame in a venue that was, for once, not a fabricated set—and there was no domineering director barking orders at her through a megaphone. In fact, both the father and the daughter, as principal actors in this “homecoming” scene, had in some sense built the set with their own hands. During his long absence from Chang On, Sam Sing had continued to send funds to his first wife, who was raising their son by herself. When Anna May began to make money as an actress, she gave part of her income to her father to help him with the upkeep of his two families. With steady financial support from Sam Sing and Anna May, her half-brother had been able to study in Japan and eventually graduate from the prestigious Waseda University, and the family had also been able to buy quite a bit of land and property in Chang On. The house Anna May was now entering—a two-story, half-timber and half-brick structure typical of southern China—had in fact been built with the money the father–daughter team had earned with sweat and toil over the years.16

After sending young Richard off to school, Anna May and her father chatted for a while on the stone steps of the house, and then went back inside. Newsreel Wong’s footage showed only a passing glance at the two sitting at a wooden table while enjoying tea together. The film quickly cut to a lengthier scene outdoors, in which Anna May and her father walked around to survey the fishponds and surrounding fields. As she later recalled, perhaps she was overwhelmed by the strange sense of standing on the land walked on by generations of her ancestors, for she felt a deep connection to that corner of the earth that was almost “heavenly.”17

In the ensuing days, visitors from Chang On and more distant villages came to take a peek at the film star. “Many women could not believe I really existed,” she recalled. “They had seen me on the screen but they thought I was simply a picture invented by a machine.” For most, she might as well have been a fairy princess descending from the sky. Following tradition, a big banquet was held for the entire village to celebrate her “homecoming.” It was a communal feast of forty-three courses, and, in order to be polite, she had to eat “liberally of all of them.”18

After spending a few days in her ancestral land, Anna May returned to Hong Kong, where another pleasant surprise awaited her. Her old friend Warner Oland, having played Charlie Chan about a dozen times, had come to China for a quick tour of his “homeland” and to promote the new Chan movie that would hit Chinese theaters later that year: Charlie Chan in Shanghai. Unlike his character’s fictional journey, which is troubled from the start by murderous malfeasance aboard ship, Oland’s arrival in Shanghai on March 22 via the Empress of Asia was a celebratory event witnessed by hundreds of fans and journalists. They referred to him as Mr. Chan and saluted his “homecoming.” As I have described in Charlie Chan, Oland, always a good sport, reciprocated the Chinese enthusiasm by staying in character and blurring the line, as usual, between fiction and reality. During a press conference, he responded to questions by maintaining the Charlie Chan persona, riffing a few Swedish-accented Mandarin lines from the movies.19 After a quick trip to Peking, Oland landed in Hong Kong on the last leg of his China tour.

Delighted that their paths crossed in that corner of the world, Anna May treated her longtime costar to a dim sum lunch. Over a tableful of delicacies, the two compared notes about their China trips. Despite the huge gap in their backgrounds—a Swede and a Chinese girl from Los Angeles—they had one thing in common: Each had made a career out of portraying Chinese, which had brought them both fame and notoriety. The significance—or, rather, the irony—of this rendezvous did not escape the notice of some sharp-eyed Chinese observers. The famous cartoonist Wang Zimei drew a somewhat satirical sketch accompanied by a parodic vignette, titled “Anna May Wong and Charlie Chan (Warner Oland).” Set against a noirish background of a bat flying over a ghostly tree under a full moon on one side and soft willows and a ribbed sail with a boatman’s silhouette under a new moon on the other, we see an immaculately dressed Charlie Chan/Warner Oland with a smooth haircut looking quizzically at Anna May Wong, clad in a trendy cheongsam. The imaginary dialogue between Anna May and Oland in his double role is light banter:

WONG: Your trip to China as the great Detective Charlie Chan seems to be going quite well.

CHAN: Thank you so much! Have you not also received a warm welcome from your compatriots?

WONG: Yes, but they are not so impressed by what I’ve done. As you know, due to restrictions of Hollywood I had to play some roles not so flattering to Chinese. Even though I haven’t been officially criticized, the fact that my hometown folks refused to let me visit really broke my heart.

CHAN: So sorry, Miss Wong grieve over such affair, but it was ineluctably a misunderstanding.

By putting words into the duo’s mouths, the anonymous author aptly captured the dynamics at work in this global mishmash of icons and meanings. While most Chinese conveniently forgot Oland’s role as the insidious Dr. Fu Manchu and chose to embrace him as the honorable Detective Chan, they found it hard to forgive a Chinese woman for ostensibly tarnishing the image of China. As Charlie Chan says, “Public mind is fickle like spring weather”—except, Anna May learned, when it came to Chinese women.20

Cartoon depiction of Warner Oland and Anna May Wong, Manhuajie, 1936

The day after her rendezvous with Oland, Anna May hosted a farewell tea party at the Hong Kong Hotel, an enjoyable event attended by the US Consul General and his wife; Peter Sin, Paramount’s rep in Hong Kong; and others. After the party, and under the cover of darkness, she left for the dock and, once again, boarded the SS President Coolidge.21 Bound for Shanghai, she would continue her rocky romance with a land she still hoped to call home.