6 CURIOUS CHINESE CHILD

CURIOUS CHINESE CHILD

IN 1915, AS EUROPE became mired in a protracted war with devastating international reverberations, Hollywood experienced a sea change.

By the second decade of the twentieth century, the movie industry had gained respectability as a form of mass entertainment. Rising from its cradle in largely eastern cities, the industry had already begun to move westward to Los Angeles in the previous decade. Mythmakers of Hollywood claim that the formerly obscure suburb of Los Angeles became the site of the motion-picture colony because the first filmmakers who arrived were fugitives—independent producers evading legal hassles and the monopolizing Patent Trust in the East. They wanted to be, so the story goes, “as far from New York and as close to the Mexican border as possible.”1 Debunkers of this myth are quick to point out that the first movies produced in Southern California were made by the Patent Trust, and that Mexico was a long, five-hour drive from Los Angeles in those days. The more plausible explanation lies in the physical environment of the region. Offering year-round sunshine and warm weather for outdoor shooting, Southern California also boasts a geographical ensemble comprising mountain, forest, desert, city, and sea, making any conceivable backdrop within easy reach of downtown Los Angeles. Economically, land was available and affordable in Hollywood, allowing producers to purchase large tracts to build studios. And, as an added incentive, Los Angeles was an open-shop, nonunion city with a constant stream of new residents, providing a steady supply of cheap labor for a rapidly expanding industry. The combination of all these factors led to a geographical shift between 1907 and 1913 as film companies moved toward the West Coast.2

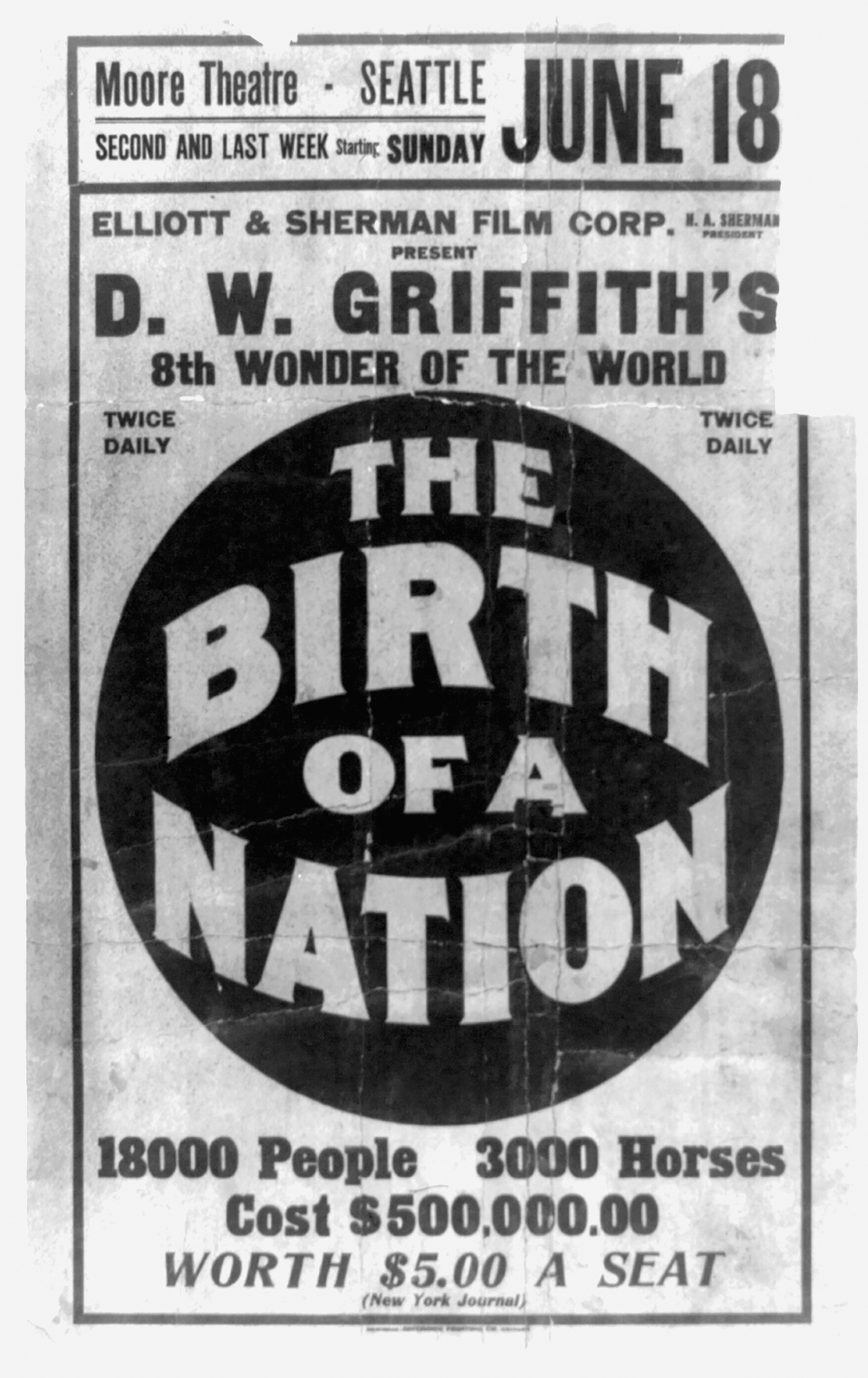

Using Hollywood as its headquarters, filmmakers began an industrial-scale model of mass production, in the process grabbing the lion’s share of the American public’s imagination, not to mention its money. The most successful production opened in 1915: D. W. Griffith’s epic, The Birth of a Nation, touted as one of the greatest visual experiences in the history of filmmaking. Running for an unprecedented dozen reels, or two and a half hours in screen time, the then-longest film ever made was based on Thomas W. Dixon’s novel The Clansman, which glorified the rise of the hooded Ku Klux Klan in the postbellum South and ridiculed Black aspirations for political rights. The son of a wounded, impoverished Confederate officer in Kentucky, Griffith was ideologically sympathetic to the theme of The Clansman. In the motion picture, Griffith found a powerful medium for propagating the message of white supremacy and the fear of miscegenation at a time when such racist sentiments were on a steady rise. The Nativist Era of the 1910s and 1920s, one of the most xenophobic periods in American history, had just begun.

Besides this explosive message, what made The Birth of a Nation such a blockbuster was Griffith’s style of narrative and his creative use of the camera. Failing in his earlier ambition as a writer, Griffith had done some acting with little success, but he found his calling in filmmaking. While early films typically were made by anchoring the camera in a fixed position, Griffith, the literary aficionado, drew inspiration from nineteenth-century novels and moved the camera freely through space and time. A skeptic once asked, “How can you tell a story jumping about like that? The people won’t know what it’s about.” In response, Griffith invoked the authority of a master narrator in a different medium: “Well, doesn’t Dickens write that way?” In some sense, Griffith, dubbed “The Shakespeare of the Screen,” realized his literary ambition not with the quill but with the camera. Like a Jamesian portrait of a lady, Griffith moved the camera “so close to the actors that human figures filled the frame. In some shots they were actually larger than the frame and were shown only from the knee up. For the first time viewers could see facial expressions throughout the film.” And like an epic Tennyson poem, Griffith told parallel stories, cutting back and forth between scenes and settings, between long and short shots, creating a dynamic montage of filmlike length. Added to these technical innovations were the spectacles of costumes, architectural form, and crowd movement. With no cost spared, the lavish display was so powerful and appealing to the audiences that they spontaneously applauded at scenes of Klan members rescuing whites from evil mulattoes and lustful Blacks. In the words of Vachel Lindsay, those climactic scenes and the emotions aroused were “as powerful as Niagara pours over the cliff.”3

Film poster for D. W. Griffith’s “8th Wonder of the World,” The Birth of a Nation, 1915 (Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Reproduction Number LC-DIG-ppmsc-03661)

While this potent combination of racist propaganda and technical innovation made The Birth of a Nation a huge success at the box office, the film also spurred key changes in the industry. The increasingly popular use of close-up shots, in particular, would contribute to the creation of the star system in Hollywood. Early cinema often presented anonymous bodies on screen without credits, whereas close-up shots enabled an emphasis and focus on the actor’s face as a fount of meaning. In other words, viewers could finally see facial expressions of characters, with “picture personality” a desired effect. Echoing Adolph Zukor’s slogan “Famous Players in Famous Plays,” Hollywood finally figured out that stars sold pictures. Name recognition and branding, then, became the magic formula for success. In tandem with these technical changes, the trade press began to publish articles about film actors, circulating information that identified and promoted the images of individual performers. Public interest in all aspects of their lives further increased the value of these actors. Mary Pickford, a child actor in the theater who successfully switched to a career in film under the tutelage of Griffith, was one of the glossiest stars of the silent era. By 1915, she could demand $4,000 a week, with her salary going up to $10,000 a week the next year—this in addition to half the profits of the films and a guaranteed salary of at least one million dollars over two years. At the time, even beginning players with the right charisma, style, and talent could earn $2,000 to $5,000 a year for their film roles.4 These numbers, astronomical in the eyes of the public, played a big role in Hollywood’s rise in cultural sway. The term movie mogul came into use around 1915, aptly describing those foreign-born producers, mostly Eastern European Jews, who became “part splendid emperors, part barbarian invaders,” seizing cultural authority via the new popular medium.5 By this point, Hollywood had become—to borrow a cliché—a place, a people, and a state of mind.

It was in this period that Anna came of age, becoming obsessed with the movies and the glamour of being an actor. “At a very young age, I went movie-crazy,” she recalled. In fact, she first went to the cinema at the age of ten, using the tip money she had saved from laundry deliveries to buy a ticket. Historians of early American cinema have emphasized the particular appeal of those grubby nickelodeons to poor immigrants, the recently urbanized working class, and women. In Babel and Babylon, Miriam Hansen suggests that the nickelodeons, filling a market gap with their low admission fees and flexible schedules, offered the spectators—most of whom had little disposable income or time—“an escape from overcrowded tenements and sweatshop labor, a reprieve from the time discipline of urban-industrial life.” Naturally, catering to an audience of such social composition, these movie theaters, particularly the ones that young Anna frequented on Main Street in Los Angeles, not far from Chinatown, were not the most stylish places—they were a far cry from the “picture palaces” with art deco flamboyance or rococo motifs that were proliferating in major cities during Hollywood’s golden years. No thought was given, for instance, to ventilation or comfortable seats. In many of the films, the titles were run in Spanish, because the audiences were largely Mexican. However, crouching in the smelly darkness, not minding the Spanish titles, Anna was enthralled by the flickering images on the screen. Thereafter, she often played hooky from school and used her lunch money to subsidize her new addiction. When her father caught her, he would beat her with a bamboo stick. “With Chinese logic,” Anna said, “my father used to protest that if I had to be a bad girl and play hooky, why didn’t I play hooky from the American school, which cost him nothing, instead of the Chinese school where he had to pay tuition.”6 What Sam Sing did not realize was that his second daughter’s truancy went beyond those trips to shabby nickelodeons; she had something grander in mind.

At Christmas time, while Lulu asked for a big doll with flaxen curls, Anna wanted a whole lot of little dolls, because she had a purpose. Using her bed for a stage, she arranged those tiny dolls as truly silent actors and made up all sorts of imaginary dramas. When her younger brother James was old enough, she pressed him into service, and the two acted out plays that she had made up. Uninterested in generic kids’ games with dolls and teacups, Anna took her performances to a different level. Coming home from the movies, she would retreat to her room and practice for hours in front of the mirror the scenes that most appealed to her. As if anticipating the countless tragic roles she eventually would undertake, she often rehearsed those screen moments of agony: crying in anguish, with tears streaming down her face. She would even clutch a handkerchief to her bosom and then tear it in a paroxysm of sorrow.7 Her melodramatic reenactments would be a perfect match for the overly wrought style of the era.

Anna’s celluloid fantasies did not stop with playacting. She daydreamed of becoming a star. In her reveries, she visualized herself in a scene where, under golden light, she wandered on a path near a white palace and scented gardens. The director, invariably a man with short sleeves and a big horn in front of his mouth, shouted, “Anna May Wong, now you can come down the stairs—We’ll do a close-up of that!” And then the photographer moved nearer with a three-legged camera, closing in on her glowing, joyful face. At the end of the scene, the director would say, “You did a great job, Anna May Wong—You are a film star!”8

Anna was not alone in her fantasies, at least not if you embrace fiction. Faye Greener, the tragic protagonist in Nathanael West’s dystopian portrayal of Hollywood, The Day of the Locust (1939), was more methodical in her reverie. “She often spent the whole day making up stories,” as the narrative goes. “She would get some music on the radio, then lie down on her bed and shut her eyes. She had a large assortment of stories to choose from. After getting herself in the right mood, she would go over them in her mind, as though they were a pack of cards, discarding one after another until she found the one that suited.”9

They were called “movie-struck girls.” Generations of young American women came to be lured by the glittering promises of a career in Hollywood, swept up by that mirage colloquially known as “The Dream Factory.” At a time when the names and faces of Mary Pickford, Alma Rubens, Ruth Roland, and Pearl White were ubiquitous on marquees, posters, and lobby cards, magazines and newspapers all hyped stories of their glamorous lifestyles and sky-high salaries. Any girl with a spark of imagination and a smidgen of ambition might ask, “Why not me?” Whether they hailed from Kalamazoo, Michigan, or Cottage Grove, Wisconsin, they all bought one-way tickets to Los Angeles.10 When they stepped off the train at Central Station (and later Union Station), or when they joined the long lines of determined young women standing outside Hollywood casting offices, or, if they were lucky enough, when they got as far as the notorious “casting couch,” what awaited them would spawn, among other forms, a new genre of American writing in the 1930s and 1940s called noir. With cold-eyed realism and hard-boiled language, authors such as Nathanael West, John Fonte, Raymond Chandler, and James Cain would portray the brutal reality facing these Faye Greeners, who had to sell their bodies and souls just to get a part as an extra in a two-reel farce in which they spoke only one line or nothing at all. The Dream Factory would, in the words of West, turn into a “Dream Dump.”

But we are getting ahead of the story, so let us get back to the girl dreaming in her father’s Chinese laundry.

Fortunately for Anna, she had no need to hop a train to Hollywood; instead, Hollywood came to her. As we saw earlier, the seemingly exotic atmosphere of Chinatown, with its curio shops, restaurants, crooked alleys, and teeming denizens clad in unfamiliar costumes, had always been a favorite backdrop for American movies. In fact, just as the Chinese laundry played a role in the development of film technology, Chinatown’s emergence into America’s national consciousness coincided with the early growth of the film industry. In the waning days of the nineteenth century, “slumming” trips to Chinatown became a fad. Aided by magazines that began to feature essays on the ethnic enclave, describing exotic menus in restaurants, offerings in curio shops, and the heathen ways of life there, Chinatown became a destination for burgeoning tourism. As one historian writes, “By 1909, so-called rubberneck automobiles, accompanied by a ‘megaphone man,’ who provided a commentary on the urban landscape, would take the curious spectator on a tour through Chinatown, which included visits to a joss house [shrine], a theater, and a restaurant.” Indeed, the touring automobile, with its ascending rows of seats, looked a bit like a mobile theater.11 Costing one to two dollars per person, these trips attracted mostly the more affluent who had money to spare, while the masses would have to satisfy their curiosity and cravings simply by going to the movies.

A passing glance at the titles and dates of the era’s films reveals how eagerly the producers exploited popular fantasies of turn-of-the-century Chinatown. Such films included Chinese Procession (1898), Parade of Chinese (1898), Chinese Shaving Scene (1902), San Francisco Chinese Funeral (1903), Scene in a Chinese Restaurant (1903), Scene in Chinatown (1903), Chinese Rubbernecks (1903), The Heathen Chinese and the Sunday School Teachers (1904), and Rube in an Opium Joint (1905), among others. Many of them captured real scenes in Chinatown, letting reality, to paraphrase Siegfried Kracauer, walk into the camera, while others, though staged, used the enclave as a readymade set. Like those slumming parties, film crews frequently trekked across town to shoot scenes in the Chinese quarter. With each scripted picture, Chinatown residents were regularly cast as extras or just stood around the shoots, rubbernecking, returning the favor of spectatorship. The more entrepreneurial members not only acted in films but also opened shops that lent props to the filmmakers. The wealth of the illustrious See family, for instance, came partly from rentals of costumes, furniture, utensils, and other bric-a-brac as film props. Neighborhood restaurants also catered to the Hollywood crowd, inventing menus with faux-Chinese dishes like “Chinaburger”—just a good old American hamburger stuffed with a cluster of beansprouts. As a longtime resident recalled, “You couldn’t be in Chinatown at that time and avoid being involved in the film industry.”12

Naturally, Anna, having been movie-struck at an early age, was also eager to be involved. She hung around the shoots, watching the goings-on, always hoping for a bit part. “We were always thrilled when a motion picture company came down into Chinatown to film scenes,” she remembered. She would play hooky from school to watch the crew at work—even though she was at risk of being caught and getting a whipping from her teacher or her father. “I would worm my way through the crowd and get as close to the camera as I dared,” she said. “I’d stare and stare at these glamorous individuals, directors, cameramen, assistants, and actors in grease-paint, who had come down into our section of town to make movies.”13

In fact, her presence was so regular and conspicuous that one film crew dubbed her “C.C.C.” (Curious Chinese child). Given her tender age, however, the magic wand of Hollywood would not yet reach her. Anna had to find other ways to wiggle her way into this new film world. She began modeling coats for a furrier and then for a department store. Obviously, the innate beauty of an adolescent Anna became quite noticeable—reflected in her luminous eyes, fresh face, and stature tall for a Chinese girl (her adult height would be five feet seven inches). A restaurant on Broadway hired her just to sit around, like a mannequin in a shop window or a Native American statue guarding a cigar store. “I was atmosphere,” as she told a journalist years later.14

When the door of Hollywood finally opened a crack, she was needed, unsurprisingly, for nothing else but atmosphere, a proverbial face in the crowd. For Anna, however, it became the first step on a journey of a thousand miles.

Anna May Wong, 1927 (Courtesy of Everett Collection)