The Working Class and the Popular Movement in Egypt

Joel Beinin

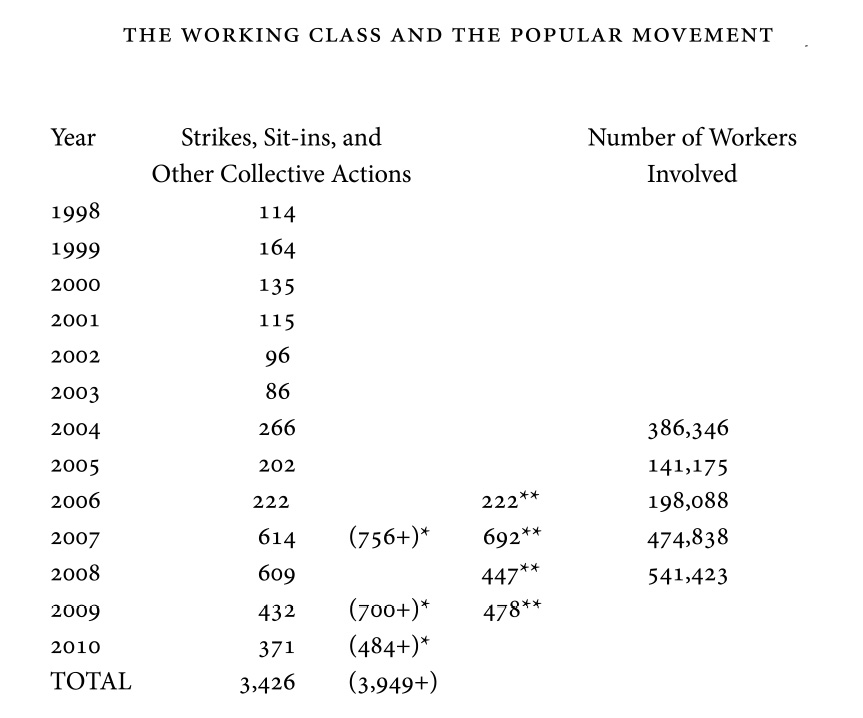

In the last decade of Husni Mubarak’s rule, the longest and strongest wave of worker protest since the late 1940s rolled through Egypt. Beginning to swell in 1998, it spiked following the installation of the “government of businessmen” in July 2004 and that government’s accelerated implementation of the neoliberal project. Some 3 million workers participated in 3,500–4,000 strikes, sit-ins, demonstrations, and other collective actions from 1998 to 2010, reaching over 600 per year in 2007 and 2008 (see Figure 9.1). Worker militancy remained high up to and through the 2011 revolutionary upsurge.

From their center of gravity in the textile sector, the strikes and protests spread to the makers of building materials, Cairo subway workers, bus drivers, garbage collectors, bakers, food processing workers, tax collectors, and many other blue-collar and white-collar workers, as well as doctors and other professionals. Like almost all strikes in Egypt since the 1950s, these work stoppages were “illegal”—unauthorized by the state-sponsored Egyptian Trade Union Federation (ETUF) and its national and local affiliates. But unlike strike waves in the mid-1980s and early 1990s, which were largely confined to state-owned industries, during the 2000s as many as 40 percent of protesting workers were employed in the private sector, where there were very few local trade union committees. This development was unprecedented in post-1952 Egyptian labor history.

Wildcat strikes and protests were frequently successful in bread-and-butter terms, winning higher wages and better working conditions or stopping proposed cutbacks. The government was eventually forced to raise the basic monthly minimum wage to £E 400 (about $70): wholly inadequate, but nearly four times the previous rate. However, the most important gains by workers in the period leading up to the revolution were political, with the establishment of four independent trade unions. These included the Independent General Union of Real Estate Tax Authority Workers in 2008, the largest of the four, followed by the General Union for Health Technicians, the Independent Teachers

Figure 9.1 Collective Labor Actions and Number of Workers Involved, 1998–2010

*LCHR considers a series of actions over a dispute in a workplace (a petition, a demonstration, then a strike) as one action. The larger figures in parenthesis (when available) count each individual action.

** Figures according to Khalid ‘Ali ‘Umar, ‘Adil Wilyam, and Mahmud al-Munsi, ‘Ummal misr, 2009 (Cairo, 2010), 17.

Source: Markaz al-Ard li-Huquq al-Insan (Land Center for Human Rights), Silsilat al-huquq al-iqtisadiyya wa’l-ijtima‘iyya, no. 5 (December 1998); no. 14 (April 2000); no. 18 (May 2001); no. 22 (March 2002); no. 28 (March 2003); no. 31 (January 2004); no. 34 (July 2004); no. 35 (February 2005); no. 39 (August 2005); no. 42 (January 2006); no. 49 (July 2006); no. 54 (February 2007); no. 56 (July 2007); no. 58 (February 2008); no. 65 (March 2009); no. 75 (March 2010) no. 76 (May 2010); no. 79 (July 2010); no. 81 (August 2010); no. 84 (January 2011). Available at lchr-eg.org. These statistics should be considered approximations. For a more detailed version of the table see Joel Beinin, “A Workers’ Social Movement on the Margin of the Global Neoliberal Order, Egypt 2004–2009,” in Social Movements, Mobilization, and Contestation in the Middle East and North Africa, ed. Joel Beinin and Frédéric Vairel (Stanford, CA: Stamford University Press, 2011).

Union, and the Retired Workers Union in 2010. On January 30, 2011, with the historic Tahrir Square sit-in underway, these autonomous unions and representatives of workers from a dozen factory towns declared their intention to form a new trade union federation, independent of the ETUF, which had functioned as an arm of the state since it was established in 1957. This was the first attempt to establish a new institution based on the popular movement—itself a revolutionary act in a place like Mubarak’s Egypt.

Throughout the long strike wave, many more workers became engaged in building democratic networks and practices in their workplaces, challenging the ETUF’s monopoly on trade union organization by electing strike committees and other informal bodies to fill the vacuum created by ETUF functionaries’ absence. These activities involving millions of workers and their families were the largest arena for democratic practices in Egypt, until the occupation of Tahrir Square. The workers’ movement did not consciously aspire to topple Mubarak, though many despised him and especially his son Gamal (known derisively as “Jimmy”), the symbol of Egypt’s neoliberal project. But as Khaled El-Khamissi, author of the best-selling novel Taxi, said: “There is continuity between those strikes and the 2011 revolution.”

A DISTINCTION ERODES

On February 13, 2005, some twelve miles north of Cairo, 400 textile workers at the Qalyoub Spinning Company, a branch of the ESCO conglomerate, sat down on the job. They were protesting the government’s sale of their mill to a private investor, because they believed private-sector management would not maintain the levels of wages and benefits they had achieved since ESCO, like most other significant Egyptian manufacturing firms, was nationalized in the early 1960s. The strike began because the government and company management failed to deliver on promises to provide an adequate early retirement package, won in response to a shorter ten-day strike in October 2004.

Washington, as well as Egypt’s creditors at the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, pushed for privatization of the public sector beginning with Mubarak’s predecessor Anwar al-Sadat. Like Sadat, Mubarak feared social unrest, and delayed the recommended privatization measures for years before moving with relative vigor to sell off state-owned enterprises after 1991. Despite several bitter wildcat strikes, the state transferred over 100 factories into private hands between 1993 and 1999. In May 1999, IMF observers declared themselves satisfied that Egypt was finally heeding their advice. Sell-offs stalled in the early 2000s due to a recession, but regained momentum when “friends of Jimmy” assumed control of the government in July 2004. The sale of the ESCO Qalyoub Spinning Company exemplified the renewed push for privatization. Textiles, one of the largest and perhaps the most storied of Egyptian industries, were targeted. The state-owned textile sector had been in crisis since the 1970s, due to competition from East and Southeast Asia.

The first step in preparing firms for privatization is reduction of the labor force. The six ESCO mills employed some 24,000 workers in 1980; the rolls were subsequently reduced to 3,500 through a combination of attrition, hiring freezes, and early retirement packages. At ESCO’s Bahtim facility, the administrative offices, garage, and spinning mill were sold to a private investor without any obligation on his part to employ the existing workers. The striking ESCO workers believed their seniority—many had spent twenty to thirty years in the mills—entitled them to keep their jobs rather than be replaced by new workers who would undoubtedly receive lower wages and benefits.

The strikers also believed the state was divesting itself of valuable assets at bargain-basement prices. Muhammad Gabr ‘Abdallah, a night supervisor with twenty-eight years’ seniority, explained that in 1999 the company was valued at £E 60 million. In 2003 the government invested £E 7 million in capital improvements, including computerized spindles. It then concluded a three-year lease agreement for £E 2.5 million per year with a businessman named Hashim al-Daghri, expecting that he would buy the mill. Before the lease expired, al-Daghri bought the mill for the steeply discounted price of £E 4 million.

The ESCO workers were highly conscious that their strike questioned the fundamental direction of the Mubarak regime’s economic strategy. Not only were Gamal Mubarak and his entourage of US-educated economists and business tycoons intent on introducing more free-market policies, but in December 2004 Egypt also concluded a highly unpopular trade agreement with the US creating Qualifying Industrial Zones (QIZs). Any commodity produced in a QIZ whose assessed value includes 10.5 percent Israeli content receives duty-free and quota-free access to the US. Rashid Muhammad Rashid, the former minister of industry, attempted to parry nationalist criticisms of the agreement by claiming that QIZs would revitalize the struggling textile sector. Previously, various Special Economic Zones were created to attract investors with concessionary conditions of all sorts, including few or no unions.

Because of the political importance of the Qalyoub strike, activists from the Center for Trade Union and Workers’ Services (CTUWS) in Helwan supported the workers. Journalists from al-Ahali, the weekly of the “legal left” Tagammu‘ Party, and the then left-leaning English-language al-Ahram Weekly wrote sympathetic accounts. In contrast, Ibrahim Nafie, chief editor of al-Ahram, made it known that he was not enthusiastic about covering the strike in the quasi-official Arabic-language daily. The workers received no backing whatsoever from the state-sponsored Federation of Spinning and Weaving Unions. Failing to stop the privatization of ESCO, they settled for a much larger early retirement package than they had initially been offered, though less than what others had received in the late 1990s.

The ESCO Qalyoub Spinning Company strike was emblematic of the mid-2000s wave in several respects: the workers’ grievances were economic and specific to ESCO, but by no means parochial. Not only did workers in other textile mills and other industries across the country echo their grievances, but throughout Egypt workers, especially in recently privatized public enterprises, came to oppose the ravages of neoliberal policies even when they did not identify them as such. The ETUF bureaucracy, which in the 1980s and 1990s had sometimes foiled privatization and other neoliberal schemes through foot-dragging and passive resistance,1 was now completely in the regime’s pocket. Workers with grievances were thus forced to organize themselves for struggle. Even if they rarely targeted the regime itself, their self-organization and demands constituted a practical challenge to neoliberalism that began to efface the distinction between the “economic” and the “political.”

AN AMBIVALENT OPPOSITION

This erosion occurred from the bottom up, through the experiences of workers themselves, rather than the interventions of the organized oppositional intelligentsia. That intelligentsia lacked the credibility and grassroots support to provide political leadership.

In the 1970s and 1980s, the “legal left” Tagammu‘ party was closely connected to workers, publicizing and offering material support to their struggles. It issued a workers’ magazine and covered labor affairs regularly in the pages of its weekly al-Ahali. In addition, several independent workers’ newspapers based on industrial regions or sectors were established.2 During the 1990s the party lost most of its popular base, amidst a general retreat of leftist politics, because of the party’s strategic decision to support the Mubarak regime in its battle against the Islamist insurgency based in southern Egypt and the urban slums of Cairo and Alexandria, and eventually against the non-violent Muslim Brothers as well. This strategy was the brainchild of Tagammu‘ chief and former Communist Party leader Rif‘at al-Sa‘id. It was embraced by the underground Communist Party, some remnants of which work actively inside Tagammu‘.

The rest of the Egyptian left embraced a more or less Nasserist perspective that effectively separated the “national question” and the “social question,” even as they paid lip service to the organic link between the two. The result was the subjugation of the demands of labor and other social justice movements to the nationalist agenda of opposition to Western imperialism and Israel’s dispossession of the Palestinians. There was a link, of course, between the strike wave and US domination of the Middle East in alliance with Israel, as the neoliberal program that sparked the strikes was heavily promoted by the Mubarak regime’s US ally. But few opposition intellectuals were able to translate their slogans against Zionism and imperialism into concrete support for labor—the one social movement in Egypt with a mass base and a record of measurable victories.

The largest and best organized political opposition movement of the late Mubarak era, the illegal but semi-tolerated Muslim Brothers, adopted a two-faced policy toward labor. The Brothers have never had a strong base in the industrial working class. Indeed, they have a long history of breaking strikes and opposing militant trade union activity going back to the 1940s, when they clashed with communists in the textile center of Shubra al-Khayma, north of Cairo. In the 1980s and 1990s, the Brothers were allied with the so-called Labor Party in which ‘Adil Husayn, a former communist who became an Islamist, was prominent. During this period, some Islamists spoke more frequently about the importance of “social justice.” After Husayn’s death in 2001, the Brothers reverted to their traditionally pro-business stance. Some Brothers verbally supported the mid-2000s spate of worker activism. There have long been differences between the affluent businessmen who dominate the leadership and rank-and-file members from the middle classes and working poor. Following the ouster of Mubarak, leading Brothers have repeated the imprecations of the SCAF and the state-run media against the “special-interest protests” (ihtijajat fi’awiyya) of discontented blue- and white-collar workers.3

The pro-business attitude of the Brothers is exemplified by Ahmad ‘Abd al-‘Azim Luqma, the former owner of the Egyptian–Spanish Asbestos Products Company (Ora Misr) in Tenth of Ramadan City, one of six satellite communities built by the state to ease population pressure in greater Cairo, hosting a Special Economic Zone and a QIZ. In November 2004 Luqma, who was known as a member of the Brothers, closed the factory and fired all his workers after the Ministry of Manpower and Migration fined him for health code violations. Luqma absconded without paying the legally required severance pay. The workers won some of their severance pay after a ten-month campout at the factory and in front of ETUF headquarters.

The historical record did not deter the Mubarak regime from trying to discredit militant workers by tying them to the Brothers. In March 2007, and again in April, nearly half of the 12,000 workers at Arab Polvara Spinning and Weaving in the coastal city of Alexandria went on strike. It had been a fairly successful enterprise privatized in the first tranche of the public-sector sell-off during the mid-1990s. When it became less profitable, workers struck to protest discrimination between workers and managers in the allocation of shares when the company was privatized; failure to pay workers dividends on their shares; and the elimination of paid sick leave and a paid weekend. The demands of the Arab Polvara workers indicated that public-sector workers were correct to suspect that, even if privatized firms initially offered pay and benefits similar to those in the public sector (in some cases, the pay is higher), the requirements of competing in the international market would eventually drive down wages and worsen working conditions. Moreover, private-sector workers lacked even the weak institutional mechanism of the ETUF to contest the unilateral actions of private capital.

The government charged the Muslim Brothers with inciting the Arab Polvara strike, but there was no evidence that they played any role in this or any other labor action of the period. The Brothers’ occasional pro-labor interventions appeared to be rooted in political expediency rather than conviction. In February 2007, Muslim Brother MP ‘Abd al-‘Aziz al-Husayni announced his backing for the walkout of Misr Spinning and Weaving workers in Kafr al-Dawwar, south of Alexandria. His parliamentary colleague Sabir Abu al-Futouh, from Alexandria, followed up by issuing several statements on a Brother-sponsored website supporting the Arab Polvara strike. Earlier, Abu al-Futouh had coordinated the Brothers’ campaign to run candidates in the fall 2006 trade union elections. The government disqualified thousands of Muslim Brothers, leftists, and independents from running in those elections—consequently judged “undemocratic and non-transparent” by independent observers. Abu al-Futouh had declared that if the elections were rigged, the Muslim Brothers would establish a trade union independent of the regime, similar to the independent student unions they founded in cooperation with the Trotskyist Revolutionary Socialist group at several universities.

Yet in November 2006, after the first rounds of voting were over and their undemocratic character was apparent, the Brothers’ Deputy General Guide Muhammad Habib (who has since resigned from the organization) sounded more reserved. In an interview at the American University of Cairo, Habib said: “Establishing an independent labor union requires a long period of consistent organizing. Workers are different than students because they have family responsibilities and will not lightly risk their livelihoods.”

The Alexandrian Brothers are generally considered more militant, more confrontational toward the regime, and closer to the popular classes than the organization’s other branches. Even if Abu al-Futouh was serious in his initiative, however, it was spurned by the Nasserists and the Tagammu‘, who rejected an alliance with the Islamists.4 Nowhere were Muslim Brothers involved in setting up trade union structures on the ground.

THE MILITANCY OF MAHALLA AL-KUBRA

The more political dimension of the workers’ movement—the demands for trade union independence and a national minimum wage—grew out of two large strikes by the 24,000 workers of the Misr Spinning and Weaving Company in Mahalla al-Kubra. In the final week of September 2007, for the second time in less than a year, they went on strike—and won. As they had the first time, in December 2006, the workers occupied their mammoth textile mill and rebuffed the initial mediation efforts of the ruling National Democratic Party (NDP). Yet this strike was even more militant than in 2006. Workers established a security force to protect the factory premises, and threatened to occupy the company’s administrative headquarters as well. Most important, the Mahalla workers scored a huge victory that reverberated throughout the Egyptian textile industry and beyond. After halting production for less than a week, they won a bonus equivalent to ninety days’ pay, payable immediately. In addition, a committee was formed in the Ministry of Investment to negotiate increases in extra compensation for the hazardous nature of their work, and clothing allowances. Incentive pay was linked to basic pay and subject to a 7 percent annual increase. The executive board of the company was dissolved, and the hated CEO, Mahmoud al-Gibali, was sacked. The days of the strike were considered a paid vacation.

The strike in Mahalla al-Kubra was impelled by unfulfilled promises made at the conclusion of its December 2006 antecedent. At that time, workers said they would accept annual bonuses equal to forty-five days’ pay, rather than the two months’ pay they had been promised the previous March. In exchange, Minister of Investment Mahmoud Muhi al-Din agreed that if the firm earned more than £E 60 million in profit in the fiscal year that ended in June, then 10 percent of that profit would be distributed among the employees. Egyptian statistics being malleable, it is possible to say only that Misr Spinning and Weaving reaped somewhere between £E 170 and 217 million of profit in the 2006 fiscal year. Consequently, workers claimed that they were due bonuses equal to about 150 days’ pay. But they had received only the equivalent of twenty. They also demanded increases in their clothing allowances and production incentives. Finally, the workers contended that al-Gibali took extravagant trips abroad, a manifestation of the corruption and mismanagement that squandered the company’s resources. The workers were acutely aware that this was their money, since Misr Spinning and Weaving is the flagship public-sector firm in Egypt. “Save us! These thieves robbed us blind! (Ilhaquna! Al-haramiyya saraquna!)” read one placard held aloft before the cameras.

The underlying economic grievance of the strike was that the standard of living of most workers, along with civil servants and others (to say nothing of the unemployed and marginally employed), was deteriorating sharply because of punishing inflation. The formerly “Arab socialist” government still subsidized bread and gasoline, whose prices were therefore subject to a measure of central control. But even with “the market” determining most of the cost of living, prices tended to rise on a predictable timetable. Modest upticks in the summer were conventional and generally uncontroversial, because the millions working in the public sector received their annual raises in July. But the 2007 round of price increases came after a period of annual inflation rates as high as 12 percent (according to government sources; unofficial estimates are typically considerably higher). In September, the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics announced that the price of food had risen 12.4 percent on an annual basis. Fresh vegetables, which are cultivated in abundance throughout the country, led the list with an astounding 37.6 percent increase. The impact of these price hikes was exacerbated because Muslims were then celebrating the holy month of Ramadan.

As in the past, government mouthpieces claimed that the Mahalla workers were “incited” to action by the Muslim Brothers and other opposition political parties. This charge was baseless. When representatives of the regime-sponsored National Council for Human Rights visited Mahalla to investigate, several workers displayed their NDP membership cards. Strike leaders repeatedly said that theirs was a workers’ movement and that the opposition parties had nothing to do with it. Opposition to the regime primarily took the form of opposition to the ETUF. The Mahalla workers renewed their call for impeaching the local union committee, which reported to the ETUF and sided with the regime and company management throughout 2006 and 2007. ETUF representatives were less than useless in the September strike. The head of the local factory committee resigned after he was beaten by workers and taken to the hospital. ETUF Secretary-General Husayn Mugawir announced that he would not visit Mahalla until the crisis was resolved.

As with many of the work stoppages of the 2000s wave, the immediate causes of the Misr Spinning and Weaving workers’ discontent were local and economic: unpaid bonuses and charges of venality on the part of management. But the Mahalla workers’ leadership understood the national and political implications of their struggle, although they usually refrained from saying this publicly. By challenging the economic policies of the Mubarak regime, they undermined its political legitimacy. In this challenge, they received the support of not only the bulk of the population of Mahalla, but also workers from the textile mills of Delta towns Kafr al-Dawwar and Shibin al-Kom, railway workers, and urban intellectuals.

One group of urban sympathizers was the Kifaya movement, the loose coalition of liberals, leftists, and human rights activists, most of them middle-class, which had sprung onto Egypt’s political scene in 2004 and 2005. Kifaya activists had marched in the streets of Cairo chanting “Enough!” to Egypt’s draconian Emergency Law, rampant corruption, and—most daringly—the increasingly arbitrary reign of the Mubarak clan. Creative and courageous in rhetoric and tactics, Kifaya had attracted considerable sympathy in Egypt and a great deal of positive media coverage in the West. Its core demand for “change” spawned a host of imitators, from Physicians for Change to Teachers for Change. But the group proved largely unable to mobilize effectively after the end of the Lebanon war in August 2006—and part of the reason was its lack of a wide social base. Its labor connections were slim, for instance: the few candidates from its labor affiliate Workers for Change who were not banned by the scurity forces from running in the fall 2006 union elections performed poorly.

In early September 2007, the Kifaya movement was proclaimed “clinically dead” in the pages of the independent daily al-Badil (now shuttered). But the events in the Delta mills brought Kifaya activists back into the streets, as they demonstrated in solidarity with the Mahalla workers on the evening of September 27. Some 150 activists were jammed against the front doors of the Journalists’ Syndicate by uniformed riot police and the plainclothes thugs of State Security. They were not permitted to leave until late in the night, a new tactic in the regime’s creative efforts to intimidate opposition of any sort. Several thousand security personnel of various stripes were deployed throughout downtown Cairo for the occasion, one of several indications that the State Security apparatus, the ultimate authority in Egypt, had lost all sense of proportion.

Back in Mahalla al-Kubra, the workers remained barricaded in the hulking mill. Eight strike leaders were arrested on the third day of the action. The sympathetic local police released them two days later to thunderous chants of approval from their colleagues. But the compromise proposal of an immediate payment of a forty-day bonus they presented to the strikers was derisively rejected. The leaders, who may have been compelled to make this offer as a condition of their release, then announced that the strike would continue indefinitely. There was broad support for a long and militant struggle, the threat of which brought ETUF head Mugawir (breaking his earlier pledge) and company officials to the negotiating table in Mahalla, according to a statement released by the Workers’ Coordination Committee. Such high-level negotiations could not have occurred except at the behest of State Security.

No doubt the political implications of the strike worried the state as much as the millions of dollars which company managers claimed to be losing every day it ground on. Muhammad al-‘Attar, an arrested strike leader who was in contact with the Cairo-based CTUWS, was also a key organizer of the March petition drive to impeach the local union committee, which the ETUF ignored. On September 27, after he had been released from jail, al-‘Attar told the Daily News Egypt:“We want a change in the structure and hierarchy of the union system in this country . . . The way unions in this country are organized is completely wrong, from top to bottom. It is organized to make it look like our representatives have been elected, when really they are appointed by the government.”

MOMENTUM BUILDS

Scorned by the ETUF, more workers had begun to raise the demand for independent trade unions. In early February 2007, strikers at the Shibin al-Kum Spinning and Weaving Company echoed the Mahalla workers’ call for mass resignations from the ETUF.5 Workers in Kafr al-Dawwar and other localities also adopted the idea of independent trade unions.

A landmark day was April 15, 2007, when a delegation of one hundred workers from Misr Spinning and Weaving in Mahalla al-Kubra planned a trip to Cairo to submit the resignation of 13,000 of their colleagues at ETUF headquarters and announce their intention to establish an independent union. Security forces aborted the trip: police first confiscated the license of the driver of the bus the workers had hired, and then physically blocked the workers from boarding a Cairo-bound train. Some of the Mahalla leaders contacted leftist activists in Cairo to ask for their support that day. While the demand for a representative and independent trade union appears modest and “apolitical,” it struck at one of the most important repressive institutions of the regime—the ETUF. The regime understood the implications, and refused to budge. The Mahalla workers have still not been able to establish an independent union. Because of the enormous economic and symbolic significance of their enterprise, they remain heavily supervised by security officials, even after the ouster of Mubarak. Their April 15, 2007 action, however, moved the question of independent unions to the top of the agenda for militant workers and their supporters.

This idea had circulated among trade unionists for over a decade, and was supported in principle by many progressives. Among them were the CTUWS and its general director, Kamal ‘Abbas; veteran trade union organizers like Sabir Barakat; labor lawyer Khalid ‘Ali ‘Umar, now director of the Egyptian Center for Economic and Social Rights; the prominent independent socialist ‘Abd al-Ghaffar Shukr; and others. The seeds of independence had been planted, among white-collar employees as well as among blue-collar workers. Ultimately, it was not abstract ideas about the virtues of self-organization that persuaded workers to take this dramatic step, but the experience of victory through protracted solidarity against a hostile regime.

In December 2007, 3,000 municipal real estate tax collectors occupied the street in front of the Ministry of Finance building in Cairo for eleven days. They won a 325 percent salary increase; and their action led, one year later, to creating the first independent trade union since the government-controlled ETUF was established in 1957. “Our union was born in the womb of our strike,” said the tax collectors’ union president, Kamal Abu Eita.6 It proved difficult to replicate the tax collectors’ success among industrial workers. But activist elements in the labor movement were encouraged to think big. Amidst the revolutionary fervor of early 2011, dozens of new independent unions were established, and many have affiliated with the Egyptian Federation of Independent Trade Unions. By the day of Mubarak’s resignation, there were banners in Tahrir Square proclaiming: “The Federation of Independent Trade Unions Demands an End to the Regime.”

The appearance of these banners showed that the strike wave had opened an important channel of communications between several groups of workers and radical activists in Cairo. Left-wing labor journalists had courageously covered strikes and protests, sleeping in factories or workers’ homes. By 2008 there were solidarity trips, especially to Mahalla al-Kubra in the central Nile Delta, and mobilizations of material aid for strikes. But, until the heady days of 2011, only a few dozen workers ever participated in events organized by leftist groups in Cairo.

The aspirations and limits of the urban intelligentsia were demonstrated on April 6, 2008, when the workers of Mahalla al-Kubra announced they would strike in support of the demand for a national monthly minimum wage of £E 1,200 (about $205). State Security authorities repressed the Mahalla strike and co-opted some of the worker leaders. A more ambitious plan for a general strike never got off the ground, though it was promoted by many leftists. Overenthusiastic opposition newspapers published headline stories announcing its success. In anticipation of a broad strike, Israa Abdel Fattah established a Facebook group calling on people to stay home on April 6. She received 65,000 “likes,” but there is no way to measure how many stayed home. Israa retreated from politics after she was detained for two weeks. But her initiative eventually morphed into the April 6 Youth Movement, a prominent group among those who called for the demonstration of January 25, 2011, which led to the ouster of Mubarak eighteen days later. April 6 members and supporters are largely upper middle class, and most of them initially opposed linking the “national” demand for regime change to the “economic” demands of workers. It was not until June 2011 that April 6 and other liberal revolutionaries began to raise slogans like “the poor first” or “a national minimum and a national maximum wage.”

The worker protests had begun to raise the latter demand in the spring of 2010. Supported by NGOs like the CTUWS and the recently established Egyptian Center for Economic and Social Rights, a growing number of workers coalesced around the demand for a national monthly minimum wage of £E 1,200 first advanced by workers at Misr Spinning and Weaving in Mahalla al-Kubra in 2008. The demand was revived when Nagi Rashad, a worker at the South Cairo Grain Mill and a leading figure in the workers’ protest movement, sued the government over its 2008 decision not to increase the national minimum wage. The basic monthly minimum wage, equivalent to about $6.35 at the current exchange rate, was established in 1984. With cost of living increases, it reached nearly $25 in 2008. Khalid ‘Ali was the lead attorney on Rashad’s case. On March 30, 2010, he won an administrative court ruling ordering the president, the prime minister and the National Council for Wages to set a “fair” minimum wage reflecting the current cost of living.

Bonuses and supplements to the basic wage—if they are paid—make it difficult to calculate actual wages precisely. But the wages of most Egyptian workers are inadequate to pay for food, clothing, shelter, and education. Even with two wage earners, the typical monthly wage of textile workers, which ranges from $45–107 per month, is below the World Bank’s poverty line of $2 per day for the average Egyptian family of 3.7 people. According to the World Bank, nearly 44 percent of Egyptians are “extremely poor” (unable to meet minimum food needs), “poor” (unable to meet basic food needs), or “near-poor” (able to meet basic food needs, but not much more).

On April 3, 2010, workers rallied in Cairo while a delegation sought to present to cabinet members a copy of the court ruling ordering the government to implement a minimum wage. After cabinet representatives refused to meet with them, they called another demonstration to support a national monthly minimum wage of £E 1,200 for May 2. Hundreds of workers gathered in downtown Cairo that day, demanding that the government implement the court order. They were confronted by a massive deployment of security forces attempting to intimidate them.

Protesters chanted, “A fair minimum wage, or let this government go home” and “Down with Mubarak and all those who raise prices!” Khalid ‘Ali told the press, “The government represents the marriage between authority and money—and this marriage needs to be broken up.” Workers brought this understanding of the marriage between authority and money to Tahrir Square in January–February 2011. While many liberal youth opposed this idea then, it became more popular after late June 2011 as more people understood that the ruling SCAF was not a neutral institution.

LESSONS OF STRUGGLE

Workers’ collective actions in the 2000s usually targeted bread-and-butter issues—the failure of owners of newly privatized enterprises to abide by the terms of the contracts in force before privatization, as the law requires; failure to pay long-overdue bonuses, incentives, and other wage supplements; failure of public enterprises to pay workers their share of profits; fear of large-scale firings before or after privatization; and low wages. Many observers wondered if or when workers might raise “political” demands. In an autocracy, however, organizing large numbers of people outside state strictures is in itself a political act.

At the appropriate moment, workers did not hesitate to fuse economic and political demands as conventionally understood. On February 9, 2011, Cairo transport workers went on strike and announced that they would be forming an independent union. According to Hossam el-Hamalawy, a well-informed blogger and labor journalist, their statement also called for abolishing the emergency law in force for decades, removing the NDP from state institutions, dissolving the Parliament fraudulently elected in 2010, drafting a new constitution, forming a national unity government, prosecuting corrupt officials, and establishing a basic national minimum wage of £E 1,200 a month. As Mubarak’s time in office ran out, similar strikes mushroomed all over Egypt, in the populous mill towns of the Nile Delta, the oil and fertilizer facilities of Suez, the sugar refineries of the southern provinces, and numerous other industrial plants, not to mention the workplaces of white-collar employees. Although there is not yet a credible insider account of Mubarak’s last days, it seems plausible that the renewed militancy of the working class was a key factor convincing the army to push the octogenarian dictator to the exit.

In the 2000s, unlike in the 1980s and 1990s, the government did not routinely repress workers’ protests by massive violence, including shooting strikers dead. The cumulative effect of the workers’ movement taught millions of Egyptians that it was possible to win something through collective, action and that the regime, perhaps because it feared scaring away foreign capital, would likely respond with only limited repression.

In March 2011, the SCAF banned demonstrations and strikes that “disrupted production” and called for calm. Nonetheless, thousands of workers, including ambulance drivers, airport and public transport workers, and even police, took to the streets, demanding higher pay, three days after Mubarak’s resignation. Since their unions do not represent them adequately, and they are not a party to the negotiations with the generals over Egypt’s political future, street protest is the only vehicle workers have for asserting their demands. The extent to which workers and others remain mobilized and willing to take to the streets may determine the extent to which popular aspirations for democracy and social justice are realized.