Economic Reform and Privatization in Egypt

Karen Pfeifer

Egypt’s economic history, from the abdication of King Farouk in 1952 to the abdication of Husni Mubarak in 2011, can be divided into three grand stages: the era of state-led development, the gradual erosion of state-led development, and the blossoming of neoliberalism. The period from 2008 to the present (July 2011), that is, from global financial crisis and recession to fragile recovery, may be a fourth stage—entailing at least the erosion of neoliberalism and, perhaps, the beginning of an era of more balanced growth with a more equitable distribution of benefits.

STATE-LED DEVELOPMENT

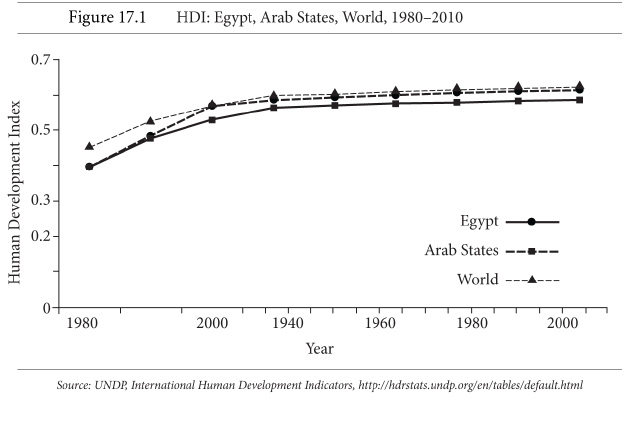

The era of state-led development, from the 1950s to the 1970s, was characterized by an enlarged role for government in the economy, with public investment in physical infrastructure, industrial production, agrarian reform, and human development. (See Figure 17.1 showing Egypt’s score on the Human Development Index in comparison with the Arab countries as a group and the world as a whole.) This process was accompanied by fundamental changes in society and the class structure. The role of foreign capital was circumscribed, while domestic private capital was subordinated and confined to the interstices of state-run institutions and state-owned enterprises (SOEs). The landlord class was shrunk by land reform and a commercialized peasantry and rural working class cultivated in its place. With the expansion of ostensibly universal public education, including at the college level, a growing middle class of urban professionals and civil servants arose, including women in the ranks of the college-educated and salaried labor force. The urban working class burgeoned, in industry, services, and public-sector firms and agencies. The state recognized the contributions of the professional and working classes and their right to form syndicates and unions, but controlled both the leadership and the finances of these institutions from the top, forbidding actions such as strikes. A social compact prevailed in which the state provided legal protection for workers’ wages, benefits, and job security, as well as universal access to public services, welfare, and subsidies for basic necessities, in exchange for political quiescence and devotion to a common project of nation-building.

The institutional fabric of state-led development gradually eroded over the 1970s and 1980s, due to both external pressures and internal contradictions. The two wars with Israel, in 1967 and 1973, were exorbitantly expensive for a low-income country and closed the Suez Canal for some years. The collapse of oil prices in the 1980s led to stagnation in neighboring countries where Egyptian migrant laborers worked. The heavy hand of central planning became overbearing and unwieldy. The complex agenda imposed on SOEs and other public-sector employers, including the absorption of all high-school and college graduates, eventually rendered many SOEs inefficient and economically unviable. The conflict between, on one hand, supporting peasant agriculture to raise rural incomes and, on the other hand, requisitioning key commercial crops at low prices to feed the urban population and to sell for hard currency grew so severe that it drove peasants into producing unregulated, but socially less rational, crops such as clover to feed cattle. The educated middle class began asserting demands for civil liberties and respect for human rights. When economic problems worsened and opposition arose, top-down authoritarianism turned brutal and repressive, in particular toward the organized working class and left-leaning political formations. Finally, the purchase of essential imports, such as inputs for industry and food to replace what was no longer produced domestically, was made increasingly difficult by the slow growth of exports, and this led to rising government deficits and international debt.

EROSION OF STATE-LED DEVELOPMENT

In response to emerging economic constraints, the regime of Anwar al-Sadat turned to the policy of infitah, or opening to foreign capital. While a private domestic capitalist class remained in the shadow of the state, the infitah helped to create a new wealthy comprador class, serving as the local agents for import/export companies and as representatives and junior partners of foreign capital. Following Egypt’s peace treaty with Israel in 1979, the United States became Egypt’s largest trading partner, source of foreign investment, and aid donor.

But the effort to curry favor with foreign capital was made without giving up the core role of the state and without major structural change in the Egyptian economy. The state economic enterprises, social contract with labor, and other promises of the Nasser era were left intact, and queues lengthened for public-sector jobs as the growth of the public sector slowed. This system was sustainable only as long as inflows of foreign currency continued apace—from aid, oil exports, foreign direct investment (mostly into the oil sector), Suez Canal tolls, international tourism, remittances from émigré workers, and a build-up of public debt to foreign lenders.

As oil prices and oil revenues declined in the mid- to late 1980s, the internal contradictions of state-led development and the region’s dependence on declining oil revenues and labor remittances came together to generate a crisis. The state’s industrialization strategy had relied on importing Western technology wholesale in large chunks of capital-intensive investment. This meant that growth in the early decades had been based on additions to capital and labor, with little technological innovation or long-term expansion in the demand for industrial labor. The combination of stagnation in agriculture and industry led to rising unemployment, rapid rural–urban migration, and expansion of the informal sector. Furthermore, in contrast to the East Asian model—Egypt is often compared unflatteringly to South Korea—protection for domestic industry had been allowed to go on for too long, with little expectation that these firms would “pay back” state support with innovation that would make their products competitive in world markets and earn their own share of foreign exchange.1 And, finally, the promise of jobs in the public sector for all graduates, and the job protections that formal-sector labor had won as part of the state-led social compact, led to overstaffing, wasted time and resources, and declines in real compensation as inflation overtook nominal wage growth.

Consequently, Egypt’s economic growth, national saving, and public spending all plummeted in the later 1980s. Real per capita GDP growth fell from an average 4.7 percent per year during the 1980–85 period to 0.3 percent per year from 1985 to 1990, and public spending was reduced steadily from its peak of 55 percent of GDP in 1985 to a low of 26 percent in the year 2000.2 This combination of internal crisis and the new reality of declining oil revenues and remittances made the Egyptian state more vulnerable to political influence from the emboldened class of importers and financiers who had flourished under the infitah, and more susceptible to pressure from the international financial institutions (IFIs).

ADVENT OF NEOLIBERALISM

International financial institutions, in particular the World Bank and IMF,were able to introduce neoliberal ideas (“the Washington consensus”) to Egypt through the role they played in tackling Egypt’s debt crisis. Structural adjustment programs required shrinking the role of the state, first through “stabilization” measures to cut government spending, reduce public deficits, and curb inflation, then through “liberalization” measures to reduce subsidies, remove price controls, and lower tariffs, and finally through “privatization” measures to sell off public-sector enterprises. Without cushioning the blows, all of these measures would create a fair amount of pain for working- and middle-class families and lead to strikes and protests.

Prior to 1990, neoliberal reforms had not made much headway in Egypt, due to resistance from organized labor and the possibility of escape for émigré workers. In reward for participating in the 1991 war to expel Iraqi forces from Kuwait, however, Egypt received a record amount of aid, $4.8 billion, in 1990–91, of which $3 billion came from the Gulf oil exporters. In addition, international creditors canceled $13 billion of Egypt’s international debt. This financial relief facilitated the regime’s agreement to an IMF-led structural adjustment program that would not cause immediate pain to the citizenry or generate strong opposition.3

The crisis years of the later 1980s and early 1990s had been a period of increasing poverty for Egypt. Yet in the early 2000s, income inequality and poverty measurements showed a less dire situation than simple per capita measures of economic growth suggested, indicating that some institutions must have been providing significant income and consumption support to the poor.4 As the state’s role was shrunk under the “stabilization” program, these functions had increasingly come to be provided by the non-profit private sector, mostly in the form of Islamic charities.5

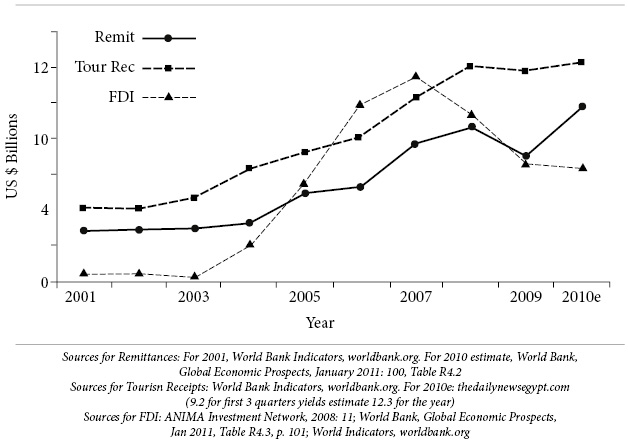

As Egypt reduced the ratio of government spending to GDP by half from 1985 to 2004, public-sector employment declined from 39 to 30 percent of the labor force. As the government liquidated holdings in 189 of 314 state economic enterprises, employment in that sector was halved, from 1.08 million employees (about 6 percent of the labor force) to less than a half-million.6 At first this appeared to validate the success of the privatization program, as the official unemployment rate fell from 11.7 to 8.3 percent and employment in the formal private sector rose 6 percentage points to 27 percent. By 2006, however, it was clear that it had been the informal sector, rather than the private formal sector, that had expanded the most, absorbing 75 percent of new labor force entrants, accounting for 61 percent of actual employment, and producing between one third and one half of officially measured GDP.7 The safety valve of labor emigration was as important as ever: in 2005–06, 2.3 million Egyptians worked abroad, and their remittances rose from an average of $3 billion from 2000 to 2003 to more than $5 billion in 2004 and 2005, as indicated in Figure 17.3 on page 219.

DILEMMAS OF PRIVATIZATION

After decades of delay, privatization in Egypt was accelerated in the second half of the 1990s, as 119 of 314 state-owned enterprises (SOEs) were fully or partially sold.8 These firms were mainly manufacturing ventures, but the government pledged to expand the privatization program to include utilities, public-sector banks and insurance companies, leading tourist hotels, and maritime and telecommunications firms. In May 1998, the International Monetary Fund, long skeptical of the Mubarak regime’s commitment to privatization, pronounced itself satisfied with the program’s progress, as measured by the proceeds going into the central treasury.

These developments generated controversy over capital ownership and social welfare. Between 1992 and 1996, financial markets expanded and trading volume in Egypt’s stock market increased ninefold. The number of companies actively traded grew from 111 in 1985 to 354 in 1996, and the International Finance Corporation listed Egypt in its emerging markets index. Recognizing that the proponents of privatization had won the day, leftists, workers, and recalcitrant state bureaucrats sought to slow the pace of the sell-off, while progressives tried to grapple with how Egypt’s transition from state to private-sector capitalism would evolve.

HOW TO PRIVATIZE?

There are several methods by which to transfer the ownership of SOEs to the private sector. Firms can be sold directly, and in total, to another company for a negotiated price. A second option is sale through a competitive bidding process on stock offerings, either to an “anchor firm” or “strategic investor,” or to the public, without granting any single bidder a controlling interest. A third method is a voucher program, through which entitlements to purchase shares are allocated on an equal basis to all adult citizens, who may then choose either to hold their shares or to sell them. Finally, employee stock ownership plans (ESOPs) allow workers to purchase a stake in the firms that employ them.

Egypt employed a combination of these methods. By July 1998, nine firms had been sold to strategic investors, and another thirty-seven had a majority of shares floated on the stock market, while nineteen companies saw 30–40 percent stakes floated. Many of these cases had 5 to 10 percent of their sales reserved for employee purchases, with employee shareholder associations (ESAs) set up for this purpose; fifteen establishments, mostly land reclamation companies, had a full or majority stake given to employees. Twenty-five firms were liquidated and their assets sold.

Typically, neoliberal economists and lending agencies evaluate these methods according to their measure of the resulting efficiency and profitability of the firm. The underlying assumption—supportable in some but not all cases in Egypt—is that SOEs are inefficiently run, with a bloated workforce producing inferior products, all at a cost to the state. In this context, the arguments in favor of direct or strategic sales are twofold. First, they result in management by a capitalist firm presumably operating according to efficient market principles; second, the anchor should be able to infuse the firm with new capital to modernize equipment and production techniques. While some Western economists see value in broader stock distribution, on the grounds that spreading property more evenly through the society is more egalitarian and enhances popular respect for property rights, the World Bank and the American Chamber of Commerce in Egypt promoted the anchor firm model,9 with its tendency to concentrate ownership in the hands of established companies.

FEAR OF FOREIGN HANDS

A narrow focus on efficiency criteria ignored fundamental questions about the nationality of capital. Given Egypt’s prior experience with colonialism, there was widespread concern about turning over the country’s strategic assets to foreign hands. Both the direct and anchor sale models privileged foreign buyers, because—although consortia that pooled local capitalists’ resources were being organized—Egyptian businessmen generally lacked sufficient capital to bid for large purchases.

Efficiency criteria also obscured concerns about the welfare of workers in privatized parastatals. In theory, ESOPs would increase workers’ influence over management decisions, thereby leading to more humane working environments, and less resort to lay-offs. ESOPs would also ensure that capital remains in national hands, and could increase workers’ incomes. Certain Islamists advocated giving workers a controlling interest in their firms.10 While most labor activists interviewed by my colleague Marsha Pripstein Posusney in 1995 saw this as complicity in privatization, a few supported experimentation with ESOPs.

Ordinary workers expressed varied responses to these programs, most of which limited them to minority ownership. At one large textile factory, workers opposed participation in a proposed ESA because it appeared unlikely to empower them to remove corrupt and incompetent state managers.11 In addition, to the degree that ESOPs benefit only former parastatal workers, the new structure would exclude the rest of the citizenry, who were theoretically the collective owners of Egypt’s SOEs.

DOMESTIC OR FOREIGN CAPITAL?

In the 1990s, privatization dramatically increased the presence of foreign capital in Egypt. Foreign portfolio investment accounted for about 30 percent of the total market capitalization of $20 billion in 1997, with foreign investors owning roughly 20 percent of negotiable shares on the exchange. More than 700 foreign institutions and funds were involved in the Egyptian market, and several international investment funds were established to concentrate exclusively on Egyptian securities. Even government officials expressed fears that a high proportion of foreign holdings in the stock market were merely speculative, and thus could be injurious to the country’s long-term development goals.

Anxieties about multinational penetration infused the debate over how the proceeds of privatization should be used. Under advice from multilateral lenders, the government dedicated a large proportion of the proceeds directly to retiring the public-sector debt held by state-owned banks, a policy that would make the banks themselves more attractive to buyers. Others argued that the proceeds could be better spent helping to modernize and restructure some of the remaining SOEs, rendering them more competitive and hence no longer in need of sale.

Difficulties arose when foreign purchasers attempted to cooperate with local firms in submitting bids. Such a dispute scuttled plans to sell a majority stake in the Ameriyah Cement Company. France’s Lafarge Coppée was slated to make the purchase with ASEC, an Egyptian firm that provides specialized management services to the cement industry, but the deal collapsed over ASEC’s objections to Lafarge positioning itself as the lead bidder. As the minister of industry in the early 1990s, ASEC chairman Muhammad ‘Abd al-Wahhab was seen as the cabinet’s most outspoken SOE defender. He resigned from government in 1993, trailed by rumors that he belonged to a cartel of corrupt state managers making illicit profits from the cement industry’s liberalization.12

Albeit using sometimes noxious anti-Semitic language, some opposition parties claimed that parastatals would be purchased by Israelis and then deliberately managed to ensure that Egypt remained technologically backward. This specter surfaced in a debate over privatizing maritime facilities, since the Israeli ambassador had earlier revealed some Israeli companies’ interest in purchasing a state-owned stevedoring company. Initially, these concerns led ‘Atif ‘Ubayd, the public enterprise sector minister, to restrict share sales in maritime companies to 10 percent, but the government subsequently decided to postpone maritime privatization altogether.

Finally, suspicion of foreign intentions fostered disputes over the pricing of firms to be sold. Sharp disagreements between government officials and international consultants hired to evaluate the firms delayed the start of the program. Even after intense bidding for some strategic sales and oversubscription of some public offerings, a number of Western economists charged the government with demanding unreasonably high prices, while domestic critics accused it of undervaluing Egypt’s assets.13

All of this controversy resurrected and refocused historic debates on the relationship between class and nation. Was there still an Egyptian “national project” to further industrialize? And, if so, could private domestic capitalists realize it better than state managers had done? Rather than futilely opposing privatization, should leftists support Egyptian capitalists in their struggles to limit sales to foreign investors?

SOCIAL WELFARE CONCERNS

Leftists also opposed privatization because of its potentially deleterious consequences for workers’ well-being. In “mixed economies” like Egypt prior to liberalization, civil servants and public-sector workers enjoyed protection against lay-offs, access to pensions and social insurance, and even company-provided housing and day care. Along with food subsidies and price controls, these protections and benefits constituted a form of welfare. Ostensibly to ease the strain of this welfare system on government budgets, privatization typically entailed an end to guaranteed employment schemes, and was associated with broader structural adjustment programs that subjected basic necessities to market pricing mechanisms. Thus, reforms threatened to remove existing social safety nets, usually before any alternatives had been established.

Before a new labor law was passed in Egypt in 2003, which would permit mass lay-offs in both the public and the private sectors, the government promoted early retirement schemes as a means to shrink parastatals’ workforces prior to sale. Egypt’s early retirement program was paid for by a social development fund financed by foreign donors and privatization proceeds. It offered workers an up-front cash payment based on their anticipated salary losses, along with a monthly stipend. But the stipend could be less than half the pension the worker would have received under the old system. Workers claimed that it was insufficient to meet regular expenses, and that their prospects for finding new employment to supplement the stipend were bleak. The rationale for the lump-sum approach was that recipients could invest in a small business or in stocks, and thus foster economic growth. But many were tempted to spend the money on essential large-scale expenses, such as their children’s weddings. Those who did so, or whose investment schemes failed, would thus face a dismal future. Workers also wondered whether their jobs could be saved if the government instead invested the early retirement funds in modernizing their factories.

Reports in 1997 indicated that program enrollment was falling short of government targets, and labor activists charged that some workers were pressured into enrolling under threat of wage cuts or transfer. The rate of acceptance was rising by 1999, however, as workers increasingly feared that once a new labor law was enacted, they would risk being fired with no compensation whatsoever in a country that lacks unemployment insurance.

This controversy raised key questions about Egypt’s “moral economy.” Were jobs a right that required the government to be an employer of last resort? Or should leftists push for Western-style unemployment and welfare systems to protect workers from the ravages of capitalist labor markets? In principle, there was no reason for progressives to oppose the replacement of universalistic protection schemes with targeted programs—why should governments subsidize the well-off? But effective social safety nets require accountable and efficient governments. In the 1980s, when the Mubarak regime considered replacing food subsidies with cash grants and ration cards for the poor, some economists voiced legitimate objections that corruption and bureaucratic incompetence would prevent the aid from reaching the truly needy. These same problems would confront any program to provide unemployment relief.

IMPACT OF PRIVATIZATION ON WOMEN WORKERS

The status of women improved significantly under state-led development, albeit from a very low base. Female literacy in 2001 was just 45 percent, but female gross school enrollment was 72 percent in that year. Women workers had fared relatively well in the public sector, where there was no formal discrimination by gender, with adequate provisions for maternity leave, nursing breaks, on-the-job child care, and equal pay for equal work. With structural adjustment and privatization, however, public-sector employment shrank, and social pressure against women pursuing a career increased, with reports that early retirement schemes in the public sector were actively targeted at women.

Furthermore, in the private sector—the alleged engine for future growth—there was a 40 percent differential between male and female earnings, and private-sector employment was becoming defeminized, resulting in higher unemployment rates for females. While more than a third of women were in the labor force in 2001 (45 percent of the male rate), the female unemployment rate rose to four times that of men by 2004, with the trend more pronounced among educated women.14 The result, as Eric Denis shows in Chapter 19 of this volume, was that fertility rates rose among stay-at-home wives.

CONTESTING THE LABOR LAW OF 2003

Under the labor law that prevailed until 2003, all permanent employees in large establishments (those employing a minimum of fifty workers) were entitled to job security and social protection.15 Egyptian labor legislation, dating from the 1950s and 1960s, was extensive. It required formal written employment contracts, guaranteed social insurance to permanent, full-time workers, and rendered dismissals difficult. Special labor offices were charged with ensuring compliance with the law, and labor courts were created to handle disputes. Employees received pensions, health and accident insurance, and, in some cases, access to public housing. These positions were offered to high-school and college graduates as a way to encourage education, and came to be viewed by students and their families as an entitlement.

Laws were more consistently enforced in the public sector than the private sector, however. Domestic private firms often found ways to evade the labor laws. The most common form of evasion was to force workers to sign undated resignation letters at the time they were hired, falsely stating that they had received their severance entitlements. Some business owners also bribed labor inspectors to report fewer than fifty employees on their payrolls, thereby reducing their mandatory insurance contributions and impeding unionization. Foreign multinationals, however, were under more scrutiny, as with the public sector. Labor markets therefore became segmented between parastatal workers, civil servants, and employees of large foreign-owned firms, who enjoyed legal protections, and private-sector workers who did not.

Organized labor, with its core strength in the public sector, had successfully staved off several efforts by the regimes of Anwar al-Sadat and Husni Mubarak to liberalize the economy and privatize the public sector in the 1970s and 1980s. Egypt’s trade unions finally agreed to support the privatization legislation designed by the regime in 1991 (Law 203), only with the proviso that all firms sold under the auspices of this law continue to abide by existing labor legislation, and that subsequent sales agreements contain clauses guaranteeing that work forces would not be reduced. But economists and the multilateral lenders promoting Egypt’s structural reform objected that these restrictions undermined the privatization program, in particular, by making public enterprises less desirable for purchase.16

The government commissioned another body to secretly renegotiate the labor law, including representatives of the Egyptian Trade Union Federation (ETUF), business organizations, the Ministry of Labor, the legal community, and the International Labour Organization (ILO). The committee’s progress was slow. The government and private business sought to restrict the right to strike, with the former apparently fearing that any form of collective protest could have a snowball effect in a time of generalized political tensions.

In essence, the negotiations were a struggle over union power—freedom of association, collective bargaining rights, and the right to strike. Union leaders, under the spotlight of the opposition press, resisted the retraction of job security or other traditional benefits enjoyed by public-sector workers, but gave ground on legal restrictions on work stoppages. Dissidents in the union movement argued that the official union leaders were too close to the government and did not represent rank-and-file workers’ concerns, and they opposed the enactment of the law. Ironically, then, the main domestic support for the new labor legislation came from the ETUF’s leadership, which gained increased power over their workers with its enactment. After protracted negotiations, the law was finally passed in 2003.17

The 2003 labor law was designed to make labor markets more flexible, an institutional change to accompany liberalization and privatization. It aimed to give employers far greater leeway in hiring and firing, changing job assignments, using “temporary” labor, and downsizing the workforce according to “economic conditions.” It gave managers greater authority to set lower wages and trim the benefits for new hires, and it revoked the annual cost-of-living adjustment to the national minimum wage. It also made it more difficult for a worker to win an appeal against a termination, and more costly in terms of wages foregone.18

The new legislation permitted multiple renewals of temporary work contracts, making it unlikely that any temporary worker could achieve the security of permanent status, or that any new worker would be rehired indefinitely. While retaining the requirement that firms obtain government approval for any mass work force reductions, it signaled a sea change by stating explicitly that employers have the right to downsize, lower the contractual wage, and/or require employees to perform different jobs than they were hired for, for economic reasons. A “grandfather clause” exempted current permanent workers from application of these provisions, but workers who lost jobs due to privatization, and then found new employment, would lose this protection. This clause apparently contributed to the cabinet’s reluctance to move the legislation until companies with excess workers had already been rationalized.19 Finally, in an explicit quid pro quo for the “right to fire,” the law recognized labor’s right to strike for the first time since 1952, but only under restrictive and tightly controlled conditions.

THE ROARING 2000S

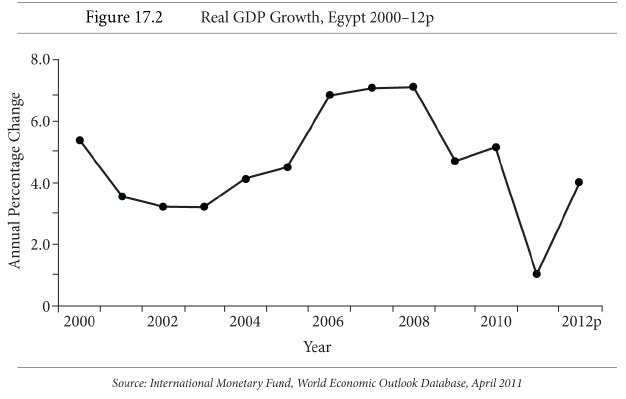

Privatization enthusiasts cheered to see stock market capitalization rise from 35.6 to 105 percent of GDP from 1985 to 2004, but the sobering reality was that the share of the formal private sector in GDP actually decreased between 2000 and 2007, from 70.7 to 62.3 percent, and that private ownership became more concentrated as the number of companies listed and traded on the stock exchange decreased by more than 50 percent—from its peak of 1,151 firms in 2002, to 435 in 2007.20 However, the new wave of reforms was credited with a surge of economic growth from 2004 to 2008, as seen in Figure 17.2.

The ballyhooed round of additional liberalizing reforms under Prime Minister Ahmed Nazif in 2004 was widely praised by the international business community and the World Bank and IMF as a breakthrough in business-friendly policies. These reforms included the lowering of inflation, taxes, and tariffs and the streamlining of documentation needed to import and export, to register property and start up new businesses, and to access credit for investment.

Long-established businesses were also well placed to benefit from the reforms. As the director of an international automaker producing in Egypt for the Egyptian market told the author in November 2006, “It used to take us days to register an incoming shipment of parts, and now it takes us hours. Nazif’s reforms have made our day-to-day operations simpler and more efficient and changed the environment to give hope to what could become a

thriving private sector in Egypt.” This company had accordingly expanded its importing of cars and shifted its emphasis in production toward light trucks for sale in the Egyptian market. Its partner in the importing and distribution divisions was none other than the minister of transportation in the Nazif cabinet.

Egypt had liberalized foreign access to almost all sectors of the economy, but with minimal impact on diversification of formal economic activity. The stock of foreign direct investment (FDI) in Egypt rose slowly in the 1990s and early 2000s but was concentrated in the capital-intensive hydrocarbon industry, with US-based oil corporations accounting for three fourths of that stock.21 Indeed, the energy sector remained the chief draw, with more than half of FDI going into hydrocarbons and related industries in the 2000s. As reserves of oil were dwindling fast but new reserves of gas were being discovered, the growth industries in this sector are natural gas extraction, oil refining and natural gas liquefaction, petrochemicals, and the building of infrastructure for Egypt to broaden its role as a major transmission station for the export of oil and gas from the region to Europe.22

Thanks to the 2003 change in labor law and the 2004 reforms, Egypt became the object of an unprecedented, but short-lived, wave of foreign direct investment from the world at large and from the Arab Gulf countries. As shown in Figure 17.3 below, FDI from all sources rose by a dizzying factor of 26 in just a few years, from $450 million in 2003 to a peak of $11.6 billion in 2007. Egypt was one of the top three Mediterranean-country recipients of FDI in 2000–08, taking 15 percent of total FDI to the MED-13 (southern and eastern Mediterranean countries) in those years.23 From 2005 to 2007, FDI to Egypt averaged 15 percent of GDP, or 200 Euros per capita.24 Foreign participation in Egypt’s stock market reached its apogee in 2007, at 31 percent of total trading volume.25

On the intra-regional level, Egypt received 7.5 percent of inter-Arab FDI from 2005 to 2009, the fourth largest recipient among Arab countries. Startlingly, Egyptian firms were even the source of 10.4 percent of inter-Arab investment in 2008, the third largest after the United Arab Emirates and Kuwait.26

According to one enthusiastic observer writing before the financial crisis of 2008 hit, Egypt was “the most integrated with the Gulf Cooperation Council investment program,” receiving about 40 percent of the Arab Gulf states’ FDI in the Mediterranean from 2003 to 2007, about $3.3 billion at its peak in fiscal year 2006–07. During that year, Egypt also received $1 billion in remittances from the Gulf states alone, and Egypt’s exports to the Gulf states were close to $550 million, including iron and steel, which made up 30 percent of Egypt’s non-hydrocarbon exports.27 Observers also applauded the Gulf states’ FDI in infrastructure as well as “manufacturing, organic farming, IGT, financial services, and logistics.”28

Figure 17.3 Remittances, Tourism Receipts, and Foreign Direct Investment to Egypt, 2001–2010

During 2000 to 2007, half of the incoming FDI to Egypt from the Gulf states went for acquisitions of existing firms rather than new projects. For example, in 2007 Lafarge of France contracted to purchase Orascom Construction, an Egyptian corporation that was listed as one of the top 100 nonfinancial transnational corporations (TNCs) from developing countries by UNCTAD in 2006. Some acquisitions entailed purchases of privatized public-sector enterprises, such as the 2007 takeover of the Egyptian Fertilizers Company by a company from the UAE. Other acquisitions were purely financial. For example, while Kuwait’s stock of investment in Egypt stood at $25 billion in early 2009, mostly in real estate, two of Kuwait’s biggest investments in 2007 had been the acquisition by the (private) National Bank of Kuwait of one of Egypt’s most successful private banks, Al Watany Bank, and the purchase by the Global Investment House, a private equity firm, of a significant stake in the Egyptian private brokerage firm, Capital Trust.29

CRASH, RECESSION, AND RECOVERY

Liberalization and privatization had clearly left Egypt vulnerable to the ravages of the global financial crisis and subsequent recession that swept the world economy in 2008–09. But Egypt’s economy turned out to be more resilient than expected, with growth declining to “just” 4.7 percent in 2009, as indicated in Figure 17.2.

Even before the financial crisis in 2008, the wave of FDI to Egypt had begun to ebb, decreasing by 18 percent from $11.6 billion in 2007 to about $9.5 billion in 2008.30 The downdraft continued in 2009, at $6.7 billion, and 2010, at an estimated $6.5 billion.31 The distribution of FDI still favored hydrocarbons, which accounted for 57 percent of FDI in 2008, while finance received 9 percent and real estate and construction 8 percent. Non–hydrocarbon-related industry received 17 percent and services took about 10 percent, but agriculture received 2 percent and ICT less than 1 percent. Of these amounts, new projects and expansions of existing companies accounted for almost one third, while privatization proceeds were about 9 percent. Contrary to the impression given by some observers, over two thirds of Egypt’s FDI in 2008 came from the West, with 33 percent from the United States and 36 percent from the European Union. Only 18 percent came from other Arab countries, mostly in finance, real estate, and construction.32

The capital market also decreased in value. From its peak in the spring of 2008 to November, Egypt’s bourse index dropped 54 percent.33 Similarly, Egypt’s stock market capitalization had peaked at 85.8 percent of GDP in 2007, then declined by half to 41.4 percent in 2009, and foreign participation fell to 19 percent of total trading value.34 Portfolio flows had already begun to shrink before the global financial crisis took shape. Egypt had experienced a rush of speculative inflows in the boom years of 2005 and 2006, following liberalization of capital markets in 2004. With the slowing of the boom and of foreign investment of all kinds in 2007, however, those speculative flows reversed themselves, creating net outflows of about 3 percent and 7 percent, respectively, in 2007 and 2008.35

There was a shift in the number and nationality of companies listed on Arab stock markets. While Saudi Arabia and Jordan added companies to their exchanges between 2007 and 2009, Egypt’s listings declined from 435 firms in 2007 to 306 firms in 2009. This drop was likely due to a wave of privatizations of public-sector companies and a strong bout of mergers and acquisitions by Gulf country firms. Egypt, on the other hand, was the main seller, with the value of its sales leaping from $1.7 billion in 2007 to $15.9 billion in 2008.36 The fact that 30 percent of Egyptian firms disappeared from the stock market from 2007 to 2009 suggests that privatization and mergers and acquisitions may have dampened competition and productive activity, rather than stimulated it.

Egypt’s nonfinancial sectors and overall growth were not much affected by the financial crisis but, rather, were shocked by the subsequent recession in Europe and the United States. In 2009, exports decreased 25 percent, Suez Canal fees dropped by over 7 percent, and both fixed investment and remittances declined by 10 percent, while tourism declined only slightly. As indicated in Figure 17.2, aggregate growth declined from the 7 percent rate in 2007 and 2008 to about 4.7 percent in 2009. The IFIs had predicted that it would be much worse, but this rate was still high enough that per capita income did not fall, and unemployment increased by one percentage point, from 8.4 percent in 2008 to 9.4 percent in 2009. What cushioned the blows were Egypt’s own peculiar strengths: its domestic informal economy, in which production and demand continued to grow, the quick restoration of remittances and tourism revenues, and a government stimulus package of new investment in infrastructure. FDI, in contrast, was of little help. As shown in Figure 17.3, it decreased by almost 50 percent between its peak in 2007 and the recession of 2009, and did not recover in 2010.

WHAT ECONOMIC PROGRAM FOR THE ARAB SUMMER AND BEYOND?

Before the January 25 uprising, most observers expected Egypt to continue liberalizing, privatizing, and globalizing. Egypt was named as a member of the next round of “emerging markets” by the Economist Intelligence Unit, and listed by Goldman Sachs among the “Next 11” economies predicted to grow faster than average and to become a force to be reckoned with in the world economy.37 Following India’s model, Egypt developed an apparently successful set of enterprise zones for Internet technology and business process outsourcing, taking advantage of the language skills of its educated population and its proximity to Europe. This sector attracted investment from Microsoft and Vodafone in 2010.38 Growth in the developing economies of the Middle East was predicted to return to its long-term trend in 2010 to 2012. Egypt, like Turkey, faced good prospects in 2010, having shown that the decline of the vaunted Gulf FDI had not had much of an impact. The major weakness in this picture was the affront to the dignity of the Egyptian people from the high level of corruption and cronyism that this course of liberalized development had entailed so far, and the inequitable distribution of its benefits.

The changes in economic policy already wrought by the “Arab spring” in 2011 and the likely changes ahead will entail neither a total retreat from a market economy, nor a plunge back into full central planning. Rather, to tackle the insulting and embarrassing excesses of liberalization and privatization, and to broaden the benefits of economic growth, the government will subject the market system to greater regulation and supervision, and will give more attention to provision of social goods and reduction in income inequality. As one Egyptian economist noted, “You have to consider that privatization is not only an economic issue; it is also a political issue that has altered the distribution of wealth and power within the society. It also has generated considerable corruption.”39

To prove its revolutionary mettle in the spring of 2011, the Egyptian investment authority overturned agreements for several direct investments, land sales, and foreign loans. In a dramatic gesture, it reneged on a deal made in 2006 for the purchase of Egypt’s famous Omar Effendi department store by Amwal AlKhaleej, a Saudi-owned investment conglomerate. Equally dramatic, and despite the IMF’s claim to promote “socially inclusive growth” in the aid and loan packages it organized for Egypt and Tunisia this spring, in June 2011 the government of Egypt revoked its earlier acceptance of an IMF loan worth $3 billion.40 On August 1, the government announced that it was canceling the privatization program for the foreseeable future. The challenge, however, is to determine a coherent and sustainable alternative program to put in its place.