4

RULE 4:

SELL PICKAXES TO GOLD MINERS

“‘You can mine for gold or you can sell pickaxes.’ This is of course an allusion to the California Gold Rush where some of the most successful business people such as Levi Strauss and Samuel Brannan didn’t mine for gold themselves but instead sold supplies to miners—wheelbarrows, tents, jeans, pickaxes etc. Mining for gold was the more glamorous path but actually turned out, in aggregate, to be a worse return on capital and labor than selling supplies.”

—Business Insider

You already know that trying to come up with a brand-new business idea is stupid if you want to get rich. There are too many opportunities for failure, but beyond that, it’s the kind of road-most-traveled thinking that rarely gets you ahead.

If you want to defy the odds, you need a counterintuitive approach. Forget trying to appeal to the masses. Look at what the masses are going after, and then sell into the market that others have built around it.

That’s the beauty of what I call “selling pickaxes to gold miners.” You let the gold miners do all the work and then siphon profits off the market they’ve created. This works in B2B selling and on the consumer side, too. So while everyone’s spending money on fidget spinners, you might sell the “Fidget Spinner Sticker Kit.” While Amazon pulls a profit from third-party sellers, you might create an inventory-tracking program for those sellers. Pickaxes are hiding behind every popular marketplace. They can be hard to spot at first, but the more you start thinking this way, the more they’ll show themselves to you.

Most people love this idea when they hear it, but it takes a lot of self-restraint to choose pickax production over gold mining. The temptation to jump into a promising industry after seeing others’ success is just too alluring. It happened to me recently when I was talking to an investor friend about venture capital. He told me that in 2014 the total amount of venture capital raised by start-ups was $48.3B. In 2016, that number hit $69.1B. Curious about the data, I started talking to other start-up founders to see what they thought of VC. Many of them privately shared that after their start-up, it was their dream to join a VC firm. The industry was doing a great job selling the sexiness of VC. My money-loving heart tried to tell me I should go into VC, too, but my brain found the smarter pickax option.

VC is the gold mine everyone wants to go after. The pickax to the VC industry is data. VCs rely on great data to make sound investments. I realized that while there are many hundreds of VC firms, they actually have limited access to company data. So I decided I’d get rich off selling data to them by launching GetLatka.com.

Some companies were already doing this, so I set out to learn + copy + do it better. Michael Bloomberg got rich off selling his Bloomberg Terminal to financial communities. He owned the data. Other companies competing in the VC firm data space included PitchBook, HG Data, Mattermark (dead), CB Insights, Crunchbase, Zirra, and Owler. I needed to find out if they were actually doing well to know whether this was a pickax I should build.

WHY DO THOUSANDS OF PRIVATE CEOS TELL ME THEIR REVENUE?

I couldn’t just call the CEOs and ask, “How much money did you make last month?” So instead, I cold-emailed them asking if I could feature them on my podcast. On the podcast, I’d ask them how much money they were making and other business metrics so I could reverse engineer their business and then fight like hell to beat them. Mattermark did $2.4M in 2015 revenue, had forty-seven employees, $18M in funding, and was doing about $275K per month as of April 2016 (dead now in flash sale to FullContact for $500K). Owler was pre-revenue but had raised $19M. CB Insights did about $8M in 2015 revenue and $14.4M in 2016 revenue. This pickax was hotter than a mouthful of wasabi if I could avoid Mattermark’s mistakes. They were selling only to VC firms at a price point of a few hundred dollars per month. Eventually they ran out of VCs to sell to and had already anchored to a price that was way too cheap. By the time they realized this, they tried to pivot to selling to sales teams but it was too late.

GetLatka.com needed to stand out if I was going to aim for a higher price point. I didn’t want it to be a data dump wrestling for attention among the established competition. That’s where my podcast came in. It was like my golden goose gave birth to another golden goose—only this one was even bigger and more fertile.

My podcast system creates two assets for me. I monetize golden goose #1, my podcast, by selling sponsor spots. These are big, six-figure deals, and I have several running throughout the year. (See this page for contract.)

Then there’s goose #1’s golden child: GetLatka.com. Once I interview a CEO on my podcast, I put the numbers he or she shares into a database. The output is a bunch of private software companies’ revenue data, growth data, etc., which I sell back to VC firms that want to connect with those CEOs so they can invest in their companies. If VCs aren’t constantly making deals, their big $500M fund dies. They have to find the top entrepreneurs, and that’s why the biggest VC firms and private equity firms are paying me between $5K and $15K a month to access this data set. I increase prices every month, so more today as you read this.

In addition, I’m doing fifteen to twenty-five new calls every week with new B2B software CEOs. Most analysts at these VC firms scrape by trying to get four to six calls a week.

Here’s what an example week might look like.

What makes my data so valuable, and worth the expense, is that it’s straight from the CEO’s mouth. Nobody has more accurate revenue data, customer count data, team size data, average revenue per user (ARPU) data, or churn data, with a source that is as reliable as the CEO him- or herself. My competitors get their data by scraping websites and blog posts for relevant metrics and customer counts and they’re never accurate. Many of them don’t even have revenue numbers. They just can’t find them.

Technically the VC firms could get this same information by listening to every episode of my podcast. But they don’t have time for that, so they pay for the database. I’m ultimately making it easier for them to consume the content that my podcast publically puts out for free.

Here’s how that works.

-

Go to GetLatka.com to see 5 percent of the full database for free:

-

Click a company you want to know more about:

-

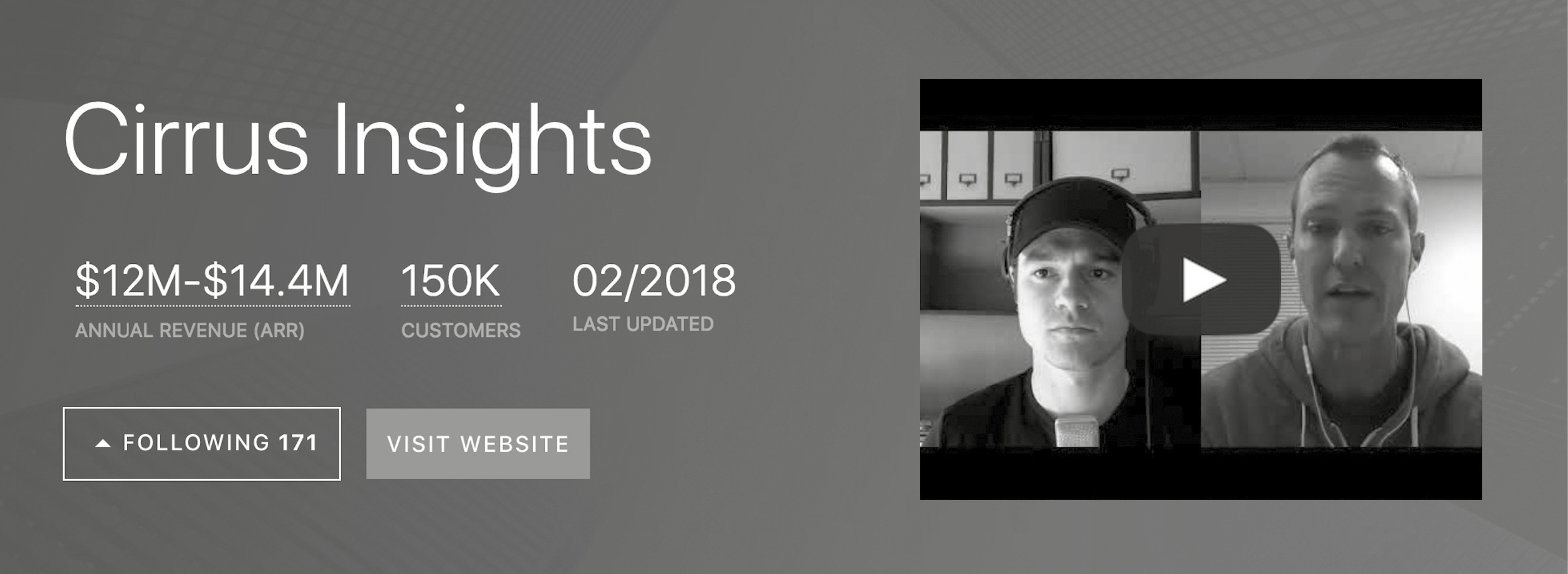

Click a data point you want to know more about (underlined). In this case, I want to hear when the Cirrus Insight CEO says, “We are doing $1M a month or about a $12M run rate right now”:

-

At timestamp 0:40 Brandon Bruce, the CEO, shares that data point. All data points in the database tie directly back to the CEO’s voice when I interviewed them for my podcast.

Short of looking at these companies’ bookkeeping, no information on them is more reliable. And it’s exactly what VC firms need to hit their investment goals. So while my friends dream of joining a VC firm to strike gold, I’m selling the firms the tools they need to be able to look for gold at all. My database made $100K in the first three months of being live, and has made multiples of that figure to date—output that I invest into other business ideas. It’s a glorious cycle of profits and investing.

LOOK IN THESE SEVEN PLACES TO FIND YOUR NEXT $5K

Some top experts will tell you to mine for lucrative business ideas by interviewing consumers on what they want. Terrible advice. Ask customers what they want and they’ll tell you about some big, sexy idea that maybe could get you rich. Anyone can ask questions like this, which means most big, sexy ideas are already being worked on. Why would you jump in and compete, all in the name of “listening to your customers”? It’s bad advice and a great way to go bankrupt.

Talk to customers but don’t actually do what they say. If customers tell you they want food delivered to their door weekly, don’t go compete with Thrive Market, HelloFresh, and Blue Apron. Rather, go figure out what those business models rely on and build that. Last-mile delivery from warehouse to consumer’s home is one of them. Onfleet.com is doing this and has just passed three hundred customers, $2.1M in 2016 revenue, and $4.5M raised. It’s a B2B software product that helps delivery companies manage and analyze their local delivery operations. HelloFresh is a customer.

This is like the part of the iceberg that floats above water—it’s big, it’s shiny, and everyone talks about it. You know the rest of this story. The bigger part of the iceberg is the part people can’t see, underwater. That’s the part you can win, the part that will bring you cold hard cash. It’s also the part that’s completely off consumers’ radar, so you’ll never hear about it from them.

This strategy has worked for generations. Remember—the wealthiest people during the gold rush were not the gold miners. They were the people who sold pickaxes to the gold miners.

If you don’t have access to a customer base, or just don’t want to go that route, there’s still plenty of opportunity to uncover pickax ideas:

-

Sell add-ons for massively popular items. Any top-selling item offers an audience that you can sell to. It’s why Amazon shows more than fifty thousand search results for the term “iPhone case.” It works. Ride a whale (Apple) and sell into it (iPhone cases).

-

Read news headlines each morning in a new way. As I write this businesses are talking about hacking; consumers are obsessed with drones, ride sharing, and on-demand food delivery; and nearly everyone is talking about cryptocurrencies. So instead of buying into cryptocurrencies, or doing your own ICO (initial coin offering), maybe you can create a dashboard for people to track ICOs. That’s taking advantage of a hot market—the crypto token gold rush. Your pickax is basically a data set that tracks ICOs, kind of like what the New York Stock Exchange does for companies when they go public.

Coinbase was built so people could manage their cryptocurrency and convert it to dollars to use in the real world while the company takes a transaction fee. Coinbase was founded in 2012 and its growth is directly tied to the media’s current obsession with cryptocurrency buzzing valuations. Coinbase raised $100M in 2017 at a $1.6B valuation.

-

Look at other marketplaces. If you offer consulting services to salespeople you might go into the Salesforce AppExchange or HubSpot—big software companies that service salespeople—and look at what’s trending in those communities. As I write this, GetFeedback, Dropbox, and HelloSign are apps trending in Salesforce. GetFeedback is software that lets companies survey their customers and then sends the data to the company’s sales team. It’s a top-ranked app, so it’s clearly making a lot of money. Well, you might launch a consulting service focused on helping salespeople understand survey results. Perfect for salespeople training. So you’re not joining the gold miners by competing directly with the software; you’re piggybacking off the market they created by offering professional services that help people use the product more effectively.

Your hack for finding clients: click on GetFeedback in the Salesforce app, see who’s left a review, and reach out to those people as the first potential customers for your new consulting service.

-

Leverage online learning platforms. See what courses are hot on e-learning platforms like Udemy. You can launch similar courses with a twist (if you have the skills people want to learn) or start a stand-alone company that serves a similar need. Mark Price did a little of both with his company Devslopes. Price started out teaching people how to code through his Udemy course. After teaching more than 40,000 students, Price launched his own learn-to-code SaaS company in 2017, Devslopes, and got 130 students paying him $20/month in the first month, for a total new recurring revenue of $2,600. Within three months that had scaled to $10K in monthly recurring revenue.

-

Eavesdrop on the influencers. What are celebrities and people with 1M+ social media influencers talking about? You’ll often see them posting from their private jets and exotic Airbnb locations. Guesty feeds off the back of the whale that is Airbnb by offering property management software for your rental property. AirDNA does the same by giving you rental data on Airbnb listings. JetSmarter tapped into the private jet community by creating a hub where people can rent out their jet or ride in someone else’s. Both companies service high-net-worth clients in an already-established marketplace. Brilliant.

Also study blogs in a space you want to go after. Which companies are they writing about?

-

Look at what’s trending on Kickstarter campaigns and other crowdfunding sites. If something gets overfunded you know that’s a hot space and things are trending generally in that direction. Consumers gave Liberty+ Soundbuds more than $1.7M via Kickstarter. Combine that with Apple AirPods, and all the other companies playing in the sound/voice space like Google Home and Amazon Echo. The upward numbers are a strong signal that sound/audio is a thriving market. All of these agencies help you build Alexa Skills to deliver your audio content to consumers with Alexa devices in your home. Their consulting agency is the pickax to the voice/audio gold mine.

-

Scan Patreon.com to see which digital products are hot. Creators in everything from comics to podcasts publish how much they’re making each month. This will give you a sense of what’s working and what’s not. At the time of this writing, I could see in Patreon’s podcasting section that Chapo Trap House is making more than $100K per month. Go to their creator page and study why their patrons are donating to them. Listen to their content and figure out why it’s so popular. This will help give you ideas about things you might build to help them serve their audiences. If you want to do something in the tech space, watch which ProductHunt.com products get the most up votes.

Ask yourself: What are these business models dependent on? All artists on Patreon have to deal with patrons who churn every month. So what if you built a Patreon add-on that helps them manage churn? You can say, “Hey, podcaster, each month one hundred of your patrons paying $50 a month churn, so you lose $5K a month. If you use our little tool it will help you save 20 percent or 10 percent of that lost revenue. Do you want to try it?” That’s a potential pickax to content creators on Patreon because they’re all selling to digital subscribers who churn. It’s a universal problem.

When you look at industries through this lens the ideas will start flying. Your task is to validate the ideas that others say they want—that tip of the iceberg. Once you know it’s legit, start building the hidden part that will keep the whole operation running. Or sell add-ons that ride the whale. You want to grab a market that’s already proven and sell into it. It should be dead obvious—gold miners need pickaxes; iPhone users need cases; Keurig owners need coffee cups. Here are some ways you can suss out whether an idea or industry is generating solid revenue:

-

Use Siftery.com to see what tools companies are paying to use inside their own businesses. You can spot winners before everyone else knows about them.

-

Use app store “top gross sales” lists to see if consumers are paying for apps.

-

Use liquor license sites to get revenue data for the bars around you (liquor, wine, beer).

-

Use investor relations links on websites to see sales of public companies.

The beautiful thing about this business approach is that once you’ve validated your idea, you don’t have to jump through hoops to convince people it’s worthwhile. Others have already done the hard work of building up the market. Now you’re just building on that whale and enjoying all the upside.

Look at video. Facebook’s newsfeed algorithm alone shows how much video’s prominence has grown in the past year. Video marketing is the future, especially if you want to reach people on social media. Well, creating videos is hard. That’s why companies like Vidyard and Videoblocks are so successful. Vidyard has raised $70M in funding, has 132 employees, and passed $8M in 2016 revenues, all from making it easy to buy and use stock videos. Videoblocks is in the same space, with $20M raised, $16M in 2016 revenue, and more than 150,000 customers.

COPY PATTERNS FROM THE PAST

Another powerful way to find your pickax idea is to apply successful business patterns from the past to today’s hot markets.

DroneDeploy did this when they started selling drone software. Since launching in 2013 they’ve raised $30M, passing one thousand customers and $1M in annual revenues. Although they’re in a new market, they’re essentially doing what app developers started doing a decade ago: printing money off software that runs on the hottest new gadgets.

Study the greats to find history’s lucrative patterns. Read biographies of successful businesspeople and identify the behaviors and strategies that got them to the top. You can also turn to documentaries—like American Genius and The Men Who Built America—to learn how pioneers built businesses.

The Acquisition + Pickax Double Punch

Ted Turner built a brilliant pickax empire by making money off the TV gold mine. Turner knew advertisers—the gold miners—were eager to reach consumers through TV. But he also recognized that TV wouldn’t be valuable to them unless people’s eyeballs were glued to it. So he set out to build amazing content.

Turner was obsessed with keeping people watching: he covered the Iraq War behind enemy lines; he bought sports teams partly so he could own their telecasting rights; he acquired World Championship Wrestling (WCW) and revived the audience for wrestling; he even made bank off of sitcom reruns and classic movies. Every one of Turner’s assets worked as a pickax that he’d then sell through to advertisers. He even gave advertisers a way to spend more money with him through branded content inside of his shows.

Turner started with a local Atlanta TV station in 1970 and went on to create a huge portfolio of networks by acquiring local stations. Then he used that leverage to keep growing. When he fought his way into the Satcom 2 launch it gave him a satellite connection that let him turn CNN into a worldwide distribution network. Now he could reach every consumer’s home.

Anyone today can copy the patterns that Turner leveraged to build his empire. He did two things on repeat:

-

He grew his business through acquisitions. Turner understood that it’s much easier to buy up companies than it is to build one from scratch.

-

He figured out what pickaxes he could sell (advertising) to the gold miners (advertisers) who were eager to profit from a hot, growing advertising space (TV).

Whatever your business or industry, remember that the gold mine is the hot trend. That’s the part of the iceberg above the water that everyone sees and wants. The pickax is the part of the iceberg below the water—the part nobody can see but that the hot trend relies on to function.

ROCKEFELLER AND HIS SULFUR PROBLEM: WORK A LIABILITY INTO YOUR GROWTH PLAN

John D. Rockefeller is another business icon who made his fortune through acquisitions. He took some major risks by taking on liabilities as he bought up assets, but his plan worked.

Most people remember, and fixate on, the 1911 Supreme Court order for Rockefeller to dissolve his Standard Oil Company for being in violation of antitrust laws. That’s one part of the story. What most don’t realize is that amid the accusations of price discrimination, spying on competitors, and the like, Rockefeller was revolutionizing the oil industry.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the hot market was light. Everyone wanted light in their house via flame—this was before Edison—and they needed kerosene to get it. So kerosene was the pickax that the gold miners (anyone who wanted to “sell light”) were after.

Part of Rockefeller’s strategy was to buy up mines full of oil that could not be processed into usable kerosene because of its high sulfur content. He took a risk, hoping he could find a chemist to get the sulfur out of the oil. It worked. To solve his problem Rockefeller hired Hermann Frasch, a chemist who had invented a desulfurization method to process oil in his own mines. He incentivized Frasch by paying him in shares of Standard Oil stock. The net result was enormous wealth for Frasch, as his method unlocked more and more usable oil for Rockefeller and his company.*

When building a business today, think about how you can work a liability into your growth plan. If you can buy an asset or a group of assets that have one common liability like sulfur, and you’re confident in your ability to solve that liability, you can unlock loads of value. That’s the essence of private equity today. And it’s the essence of a pattern from history that you should copy. The Top Inbox had a $100K liability on its books when I bought the company. I knew I could solve that liability by renegotiating it. I did and unlocked free money. More on that later.

Shrink the Time Gap

If you’re in the fast food business, or food or processing in general, read McDonald’s: Behind the Golden Arches or watch the movie The Founder. It’s incredible to see how Ray Kroc and the McDonald brothers got McDonald’s laid out so they could deliver a hamburger every few seconds with the smallest possible footprint.

They would actually map out their restaurant layout on a basketball court with chalk to perfect their process of getting a burger from the point where the consumer orders it at the front counter to delivering it to them, as fast as possible. Their obsession with setting up this system and being so maniacal about saving consumers time was a pattern that they went all in on.

The pickax to the restaurant industry is systems. Every fast food restaurant’s biggest expense outside of humans and food is typically renting the space. So you have to figure out how to do the most in the smallest amount of space. Today there are armies of software, tools, and consultants that sell restaurant layout plans, restaurant systems, and machines that consolidate the griddle and the fryer with the malt machine and the soft-drink machine to make it more efficient and take up one tenth of the space.

2018 GOLD RUSH? SELL TO AMAZON AND EBAY SELLERS?

Today Amazon is bringing that same level of obsession to saving people time. It’s building innovations in truck delivery systems, putting robots in warehouses, dispatching drones to pick up items from warehouses and deliver them to houses—all with Jeff Bezos’s singular focus of getting products to consumers faster so that they’ll buy more. And that’s why he’s the richest man alive.

Feed off that whale if you’re in this space, which is essentially supply chain management. Also think about saving sellers time. Many people are doing this by selling software to Amazon and eBay sellers. Victor Levitin created CrazyLister in 2013 in response to sellers’ frustration over the complicated process of posting items on eBay. CrazyLister lets sellers drag and drop photos, text, and design elements to customize their item listings. When they’re done they just copy and paste the code that CrazyLister generates into eBay’s back end. Within five years Levitin grew the company to $25K in monthly recurring revenue, two thousand customers, eight employees, and $600K in venture capital funding. His drag-and-drop software also works for Amazon now. There is also a whole breed of consultants that support this industry. However you approach it, if you can figure out how to shrink the time gap for people on either side of the sales process—for sellers getting their products up or customers who want those products in hand—you’re going to win.

There’s something to learn—and copy—for every successful business in history, no matter how antiquated they seem. Just look for the patterns that kept getting them the wins. They’re always lurking in plain sight.

Become an Expert, or Find One

Scouting for pickax ideas can get addictive. There’s so much opportunity everywhere you look, but you’re likely to have the most success in an industry you know, at least a little. So start by identifying hot markets in your world.

Tucker Max decoded a pickax to book publishing when he became an author. He realized there’s a huge market of people (gold miners) who want to establish themselves as thought leaders so they can charge higher consulting and speaking fees (gold mine). Publishing a book is a silver bullet to accomplishing that. The problem: most people don’t have the time or expertise required to become an author. Max immediately spotted his pickax cash cow and got to work launching Book in a Box (now Scribe Writing) in 2015. Since then the company has worked with more than five hundred authors and passed $11.3M in revenue as of September 2017. They charge clients a minimum of $25K to write their book for them, in their voice. All the client has to do is answer a few interview questions. Max realized that Book in a Box had the potential to be more lucrative than his own best-selling books, which is why he spends more time on the business these days than on his own writing.

If you’re in media, look at trends on Facebook, BuzzFeed, Google, and other big media companies. If you’re in the engineering space, look at what Boeing is doing, or what Rolls-Royce is creating. Play on your playing field and make sure you have at least some expertise there.

Then again—there’s always room to learn new things. A great way to develop expertise that you don’t already have exposure to is by interviewing people in the space. It’s one of the reasons I created my podcast. It allows me to quickly tap into the brains of people who are very smart in spaces I may not know much about, understand what they think is trending and what will be hot a year from now, and dive in. I’m doing this right now with cryptocurrencies. I’ve had many of the top cryptocurrency experts on my podcast, asking them where they see the industry going, where they’re spending their time, what they’re investing in. Their feedback gives me ideas on what the bottom part of the iceberg might be.

If podcasting appeals to you, it really is a great gateway to meeting top thinkers. Don’t worry about starting from scratch. Before I had more than six million downloads, I had zero. The trick when you’re launching is not to tell your prospective guests that they’ll be on your first episode. If you do they’ll just fixate on the fact that you have no audience. Instead, say, “My show will have a million downloads by X date.” Experts and people you want to connect with will love that kind of confidence. And it will pull them in. Once you get them live they actually help create a self-fulfilling prophecy for building your audience since they’re big names themselves.

There’s rarely a magic bullet for immersing yourself in a new industry—but Toptal is pretty close. You can know nothing about a particular business area, but post your project on Toptal and they will recommend experts for you to work with. So let’s say you want to develop an app that helps salons book appointments more efficiently. You can post that exact sentence on Toptal and they’ll help you find mobile developers. It’s that simple.

If you have absolutely zero experience in something, you’ll have to put in extra time and energy to find a Toptal freelancer because you’ll need to learn along with them. But the beautiful thing about doing this is that the person you hire ends up teaching you more and more about the space—a space you knew nothing about. So the next time you work on a project, you’ll do it more efficiently. Your work will get easier the more you do it, and your returns will compound over time.