4

Acting Strangely

Three Performances in Twin Peaks

The deconstructed figure of the femme fatale in Twin Peaks is of interest with respect not only to genre (film noir, specifically) but also to performance. Drawing from sociologist Orrin E. Klapp, Richard Dyer has taught us that a star may personify a “social type,” or “a shared, recognizable, easily grasped image of how people are in society (with collective approval or disapproval built into it)” (47). Twin Peaks is populated largely by US social types, even if some characters ultimately transcend, subvert, or at least problematize the types the series self-consciously deploys. As the previous chapter suggests, the “Independent Woman” emerges as the most recurring type, albeit mystified as the “femme fatale” through the patriarchal fears and desires the series lays bare. But there is also Kyle MacLachlan’s “Good Joe,” Dale Cooper; Dana Ashbrook’s “Tough Guy,” Bobby Briggs; and James Marshall’s “Rebel,” James Hurley, among others. This chapter considers the underexamined relationship between acting and character in Twin Peaks, focusing on three key roles: MacLachlan as Cooper, the Zen FBI special agent from Philadelphia assigned to investigate the murder of high school homecoming queen Laura Palmer; Ray Wise as respected attorney Leland Palmer, Laura’s father, who murders her under the control of the inhabiting spirit BOB, played by Frank Silva; and Sheryl Lee as Laura, a victim of Leland/BOB’s sexual abuse since the age of twelve. Although only glimpsed in the series through flashbacks and Red Room sequences, Laura is the protagonist of the feature film prequel Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me. We contend that these performances derive from the intersections of a modernist fragmentation and a melodramatic affect, constituting both the distinctive “strangeness” of the Peaks universe and its earnest appeals to pathos and emotion.

A unifying mode of address through acting would be difficult to establish here, especially given Lynch’s caginess in interviews about his directorial methods and intentions. Moreover, cast members relied on heterogeneous styles, came from various backgrounds, carried different star images, and worked with multiple directors throughout the series (to say nothing of the gap between Twin Peaks and The Return that brought new actors to the series and asked older stars to reprise their roles after twenty-six years). Andreas Halskov comments on the unusual amount of freedom and control Lynch enjoyed in casting Twin Peaks, “using mainly his intuition and his sense of the visual (how a given actor would look on screen)” (64). Lynch “signed actors to nonscripted roles or based on loose ideas he had” (67–68), sometimes inspired by only a head shot (e.g., Sherilyn Fenn as Audrey Horne) or an informal conversation instead of a traditional reading (e.g., James Marshall as James Hurley). Similar to his casting process, Lynch’s work with actors is concerned neither with characters’ “motivation and backstory” nor with “character development and consistency,” as actor Richard Beymer attested in Lynch’s direction of his performance as Ben Horne (68).

Our concerns lie in the individual performances that contribute to the structuring motif of “acting strangely”—demonic possession, doubling, reversed backward speech—and thematize performance across Twin Peaks, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me, and The Return. The hyperconsciousness of performance, we argue, makes performance itself an important narrative through line and formal component at the level of the visual style.15 Lest one forget that the metatheatrical space of the Red Room functions as a stage for revelations that both characters and audiences are invited to experience.16 James Naremore has pointed out that the camera always creates a “performance frame,” which “designates spectacle” and “can contain various kinds of performance,” including people “as actors playing theatrical personages, as public figures playing theatrical versions of themselves, and as documentary evidence” (Acting 15). For the purposes of this chapter, we will confine our analysis to “acting,” the term Naremore uses for “a special type of theatrical performance in which the persons held up for show have become agents in the narrative” (23). Indeed, a whole other chapter could be written on music and performance, from Julee Cruise’s appearances at the Roadhouse to the parade of artists Lynch curated to play in The Return.17

Before proceeding further, definitions of “modernist” and “melodramatic” performance are in order. With “modernist” cinema, we are referring to the late modernism of post–World War II art cinema (see Chapter 1). We understand “modernist” film performance in this context, as Robert T. Self defines it, “not to ultimately convey some sense of an ‘individual’ ‘identity’ but to portray personality as a subjectivity proscribed by contradictory forces. Thus, acting in modernist discourse works inevitably in the service of the depiction of splintered, unstable, and insecure identity” (127). Modernist cinema rejects the “unified social identity” and “autonomous individual” of classical cinema, which upholds characters as intelligible, as capable of ethical, meaningful action (127), and instead seeks “to represent a truer reality” through “‘people,’ not ‘characters’” (128).

This definition only partly applies to Twin Peaks, which favors characters and performance based in social types (not ordinary social reality), while opting for the excesses and exaggerations of melodrama over the “dispassionate and detached voice” of modernism (Self 127). Recall from Chapter 2 that film melodrama grew out of nineteenth-century theater. In a short article on the performance styles in Twin Peaks, Stephen Lacey observes that melodrama necessitated “an acting style that was externalized and physicalized” to articulate “extreme emotional states” that the actor could hold long enough for the intensity and expressivity of emotion to register fully with the audience (128). Wise, MacLachlan, and Lee deliver performances that tacitly assert an aesthetic and philosophical project of modernism, questioning the efficacy of traditional linguistic communication and the idea of a self that exists outside of contradiction or division. Despite reflexivity and artifice that align Twin Peaks texts with modernist experimentation and innovation, the performances of suffering, existential uncertainty, and sexual trauma afford opportunities for what Bruce McConachie calls “gaining knowledge through feeling,” a historical and affective tradition of melodrama (qtd. in Lacey 128). Twin Peaks, in the final analysis, presents models for Cooper’s vision of “looking at the world with love” (Episode 18), while exploring Major Briggs’s fear of “the possibility that love is not enough” (Episode 27).

Ray Wise/Leland Palmer

A scene in Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me encapsulates the modernist-melodramatic continuum on which we see these three actors. Leland has secretly responded to an advertisement in the swingers magazine Flesh World and just had sex with Teresa Banks, a seventeen-year-old diner waitress outside the town of Twin Peaks, who moonlights as a prostitute to support her cocaine addiction. Lying on top of her in their motel bed, he presses his hand over her eyes and asks, “Who am I?” Although clearly uncomfortable, Teresa seems to think Leland is using his hand as a blindfold to be kinky. Meanwhile, the audience knows he is wrestling with BOB’s gradual influence and losing any sense of himself as BOB continues taking over. Teresa, who sometimes “parties” with Laura, will later become Leland/BOB’s first victim when she discovers that Leland is Laura’s father and attempts to blackmail him. Echoing Leland’s question, Laura will later ask, “Who are you?” first as she sees electrical flickers on her bedroom ceiling, indicating BOB’s presence, and again when BOB rapes her and reveals himself as Leland.

Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me attributes Leland’s psychological duality to a supernatural cause (i.e., demonic possession), but this evil made manifest also has metaphorical significance as a monster from the id. BOB can be read as a psychological displacement of an incest victim unable to accept “the man behind the mask,” the name Mrs. Tremond’s grandson gives Leland, as her perpetrator (in Episode 14, Cooper learns that she referred to him as “a friend of her father’s” in her secret diary).18 The recurring image of the “phallic papier-mâché mask” (Nieland 88) extends this theatrical metaphor. Yet, BOB also represents the dark side of a father’s psyche. After the film’s release, according to Chris Rodley’s interview book, Lynch “received many letters from young girls who had been abused by their fathers. [ . . . ] Despite the fact that the perpetration of both incest and filicide was represented in the ‘abstract’ form of Killer Bob, it was recognized as faithful to the subjective experience” (xii). There are times when Wise’s performance gives Leland a fair amount of ambiguity, leaving audiences to wonder in those moments whether he is “all BOB,” such as in the sex scene with Teresa Banks. Lynch believes the path to human enlightenment is attainable through negotiating the opposites that comprise the world, including psychic opposites in oneself; in order to appreciate the “light,” one has to confront the “dark.” What Lynch describes is not so much the conservative Manichean binary that gives melodrama its moral legibility but contradictory forces that remain coterminous in nature (Rodley 23). About Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me, he has said, “Laura’s one of many people. It’s her take on that. That’s what it was all about—the loneliness, shame, guilt, confusion and devastation of the victim of incest. It also dealt with the torment of the father—the war in him” (185).

Leland, too, is a victim of abuse. In Episode 10, he identifies BOB as a man named Robertson who lived next door to his grandfather’s summer house, where he vacationed with his family as a child, and in Episode 16 he admits that BOB would visit him in “dreams.” The story Leland tells evokes the repressed memories of a rape: “He said he wanted to play. He opened me and I invited him and he came inside me.” The “war” in Leland to which Lynch refers is acted out on both diegetic and metadiegetic levels of performance. As BOB’s human vessel, Leland is forced to embody him and enact his unthinkable crimes (screaming, “don’t make me do this!” before murdering Laura).

Throughout Twin Peaks, Leland’s episodes of singing and dancing literalize BOB’s “performance.” Perhaps not coincidentally, Leland Palmer is also the name of a Broadway performer who starred in musicals during the 1960s and 1970s (Kalinak 86). Mocking Leland’s grief over the loss of his daughter, BOB has him play a recording of the jazz standard “Pennsylvania 6–5000” and dance while clutching Laura’s portrait (“we have to dance,” he tells Sarah after wailing hysterically) (Episode 2). Following Laura’s funeral, he tearfully begs guests at the Great Northern to dance with him, a kind of perverse variation on the Danse Macabre (Episode 3), and later breaks into another dancing-crying fit in front of Ben Horne’s investors from Iceland (Episode 5). As BOB’s influence strengthens in the second season, signaled by Leland’s hair turning white, Leland erupts into renditions of old pop songs and show tunes (“Mairzy Doats,” “Get Happy,” “Getting to Know You”), purporting to show his final acceptance of Laura’s death when actually revealing BOB’s delight in getting away with murder.

Frost and Lynch finally “unmask” BOB in Episode 14, although they always knew it would be Leland (Rodley 181). To conceal the twist from the cast and crew until just before this episode aired, Lynch went so far as to shoot two different versions (one with Leland killing Maddy Ferguson and one with Ben Horne as the murderer), and both were edited, mixed, and color corrected. Wise was heartbroken when Frost and Lynch informed him that the episode would reveal Leland as Laura’s murderer (“Secrets”). The camera shows BOB’s reflection in the mirror looking back at Leland, who, in another metatheatrical moment, has straightened his tie and turns behind him, breaking the “fourth wall” by looking into the camera (the sounds of a phonograph needle over the trail-off groove of a record produce a tense, heartbeat rhythm). Leland/BOB’s murder of Maddy, illuminated by a spotlight, will become a harrowing, dance-like “show,” and BOB must get into character before showtime. When Leland disposes of Maddy’s corpse in Episode 15, he sings “The Surrey with the Fringe on Top” from Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma! (1943) with wicked glee, and only in his last dying moments does he regain his soul after BOB departs (Episode 16).

Prior to his role on Twin Peaks, Wise was best known for playing attorney Jamie Rawlins on the long-running daytime soap opera Love of Life (CBS, 1951–80) between 1970 and 1976, and he had recurring roles throughout the 1980s on prime-time soaps, including Dallas, Knots Landing (CBS, 1979–93), and The Colbys (ABC, 1985–87). The acting demands of Twin Peaks required Wise to operate on a whole other level of television melodrama. In his foundational book on David Lynch, Michel Chion argues that “Lynch dared to make his actors sob, running the risk of stifling the symmetrical effect of tears among the spectators” (115). With the “welling up of tears, like a slow constriction,” Chion explains, the actor “alters and convulses the face,” which then “contorts and becomes ugly” (115).

Twin Peaks couples such heightened emotion with “a non-psychological and non-naturalistic logic of roles” (Chion 109) in “a world of archetypes” (111), such as the social and generic types mentioned earlier. Chion claims that characters run “true to type” or “acquire a mythical quality” (e.g., BOB, MIKE, the Chalfonts/Tremonds, The Arm/Man from Another Place, The Fireman/Giant) (107, 109). Another category consists of characters “singled out by some physical aspect of their appearance, such as a piece of clothing or favorite accessory which is semantically associated with them” (e.g., Audrey Horne’s sensual dancing and posing, Gordon Cole’s hearing aid, Leland’s white hair) (107–8). We would add that Wise’s grimacing facial expressions and compulsive dancing define his character by providing the visible “language” of pantomime for Leland’s experience of despair and conflict, a modernist crisis of epistemology and identity (“Who am I?”) that exceeds linguistic communication. Taking Chion’s thesis further, we could think of most characters in Twin Peaks as “actors,” in that they are defined by hair, makeup, costume, movement, gesture, and behavior. They are “non-psychological” and therefore require the external and physical acting conventions of melodrama to signify as characters. However, they do not lack the complex, deeply layered subjectivities associated with modernist representation.

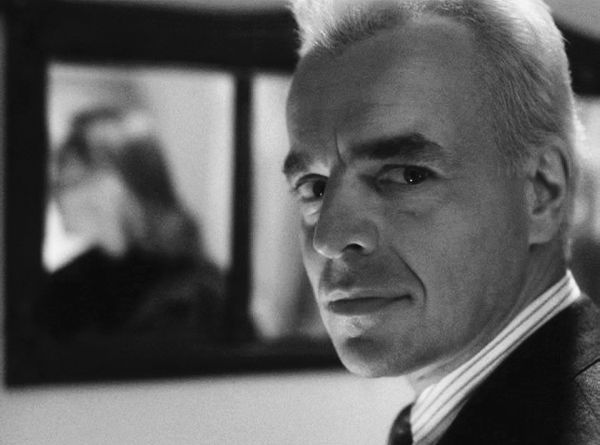

Ray Wise as Leland Palmer, reflected as BOB (Twin Peaks, Episode 14).

What makes Wise’s performance astonishing is how he convincingly juxtaposes emotions (crying and dancing) and characters (Leland and BOB) within a single scene. Wise’s code-shifting between Leland and BOB establishes a performance vocabulary that often but not always allows the audience to distinguish the characters from each other (warm smile, polite manner, and overwrought agony for Leland; scowls and evil grins, manic energy and intensity, and raspy voice for BOB). Consider the scene in Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me when Wise sits hunched on the edge of Leland’s bed, rocking back and forth with his head tilted down, mouth curled in a grin, and eyes staring slightly up from under his eyebrows. Suddenly, his grin melts and his eyes soften; his face trembles as he begins to weep. It is clear that Leland remembers sadistically reprimanding Laura earlier in the evening (as BOB) for sitting down to dinner with “filthy” hands (a veiled and jealous condemnation of her sexual activity). Leland’s pain and sorrow only provide sustenance for BOB, ensuring that this transformation is temporary, and his powerlessness imbues the scene with the pathos of melodramatic irreversibility. Audiences of Twin Peaks already know both Leland’s and Laura’s tragic fates.

Kyle MacLachlan/Dale Cooper

Whereas Wise’s performance holds in tension two selves occupying the same body, MacLachlan plays a character who splits into two different bodies: the “Good Joe” Cooper and his “shadow self” from the Black Lodge, who merges with BOB in the Season 2 finale and goes by the nickname “Mr. C” in The Return. MacLachlan rose to stardom with Lynch’s Blue Velvet and his earlier Dune (1984), an adaptation of the classic 1965 science-fiction novel by Frank Herbert that flopped both critically and commercially. In 1987, he also starred in a science-fiction action-thriller called The Hidden, playing an extraterrestrial masquerading as an FBI agent. With Twin Peaks and The Return, he demonstrated an extraordinary acting range into which previous films and television series had not fully tapped.

Fans of Twin Peaks will fondly remember MacLachlan’s sensitivity and boyish charm as Cooper, his enthusiastic “thumbs up” signs and outpourings of excitement over doughnuts, cherry pie, and hot black coffee (“damn good coffee” quickly became a shibboleth of Peaks fandom). Cooper’s wonder in discovering the majestic beauty of Douglas firs, his fulfillment by simple culinary pleasures, and his obsession with tape-recording his detailed observations and interpretations of the day—ostensibly for the benefit of his secretary Diane—reflect an awe of and delighted curiosity in the natural world. The town of Twin Peaks abounds with mysteries to be investigated, organized, and sensed (seen, heard, smelled, tasted, and felt).

It is no surprise that his method of detection combines the logic and precision of deductive reasoning with the spirituality of Tibetan Buddhism, a belief in ethical principles and community values, and a receptivity to dreams, resulting in “a mind-body coordination operating hand-in-hand with the deepest level of intuition” (Episode 2). As Martha Nochimson asserts in her pioneering feminist analysis, Cooper’s perceptive abilities are not without gendered implications for Twin Peaks as a detective series. If the “Hollywood Mystery Tradition” equates femininity with the unknowable and therefore the dangerous, traditional masculine detective heroes must transfer their fears of vulnerability onto women’s bodies (sexualized femmes fatales or desexualized murder victims) and take recourse in the narrow, culturally determined “facts” of reality (144–45). By contrast, Nochimson argues, Cooper does not disavow the feminine to restore phallocentric clarity, but rather seeks to “move between masculinity and femininity” to solve the mystery of Laura’s murder with an open mind (151).

When a dream transports Cooper to the Red Room twenty-five years in the future at the end of Episode 2, Laura whispers the identity of her murderer in his ear and “seals” her message with a kiss. “Better to listen than to talk,” the Giant later admonishes. In effect, Laura solves the mystery for Cooper at the beginning of the series (Nochimson 151); she is “neither a sexualized or desexualized object,” but rather a subject in her own murder mystery (152). Nochimson points out how Cooper “gains knowledge through merging with her” and the pleasure of her kiss compounds the satisfaction of their mutual desires: his to understand and hers to communicate (152). Over the first fifteen episodes, Cooper must learn to “‘hear’ Laura with his conscious mind” (151) and remember her words, as surrounding patriarchal figures of Twin Peaks consistently fail to guarantee authority (150). The Laura Palmer case leads Cooper to seismic uncertainty, but by relinquishing control, he also liberates himself from fear and undertakes a different hero’s journey, one of human compassion and connection.

Lean, square-jawed, and clean-shaven, with his almost permanently slicked-back hair, Cooper sort of resembles a superhero (uniformed in the Hollywood detective’s beige trench coat, black suit, white shirt, and tie instead of tights and a cape). On the one hand, his fashion sense conveys his consummate professionalism, but on the other, it shows a comfort with the senses of those around him. Cooper does a great deal of looking in his investigation and he is also looked at himself, primarily by Audrey Horne, who motivates a structure of looking that positions Cooper on the receiving end of a desiring gaze. Conceived as his exact opposite, Mr. C appears as a grotesque parody of hypermasculinity: cowboy boots, a biker’s black leather jacket, and a rock star’s mane of wild, greasy hair. To say he lacks Cooper’s sense of style would be an understatement.

Never relying on costumes or accessories exclusively, MacLachlan distinguishes Mr. C from Cooper in the way he walks and talks. The eager, wide-eyed Cooper strides through space (Chion 153), speaking with animated facial expressions and a “sing song” delivery. Conversely, Mr. C swaggers with macho bravado, his face resting in a disturbingly flat affect. Mr. C’s monotone voice and clipped, matter-of-fact speech patterns betray a crudeness of thought, a lack of emotion, and an inability to feel, with a will to violence that supplants Cooper’s wish “to treat people with much more care and respect” (Episode 8). Part 2, for example, contains an excruciating scene in which Mr. C lies in bed next to his criminal partner, Darya, who, he realizes, has double-crossed him. Ignoring her attempts to distract him with her body, he coldly attacks and then shoots her dead before proceeding to another motel room to have sex with a second female associate, Chantal. Although Chantal happily consents, the scene recapitulates the earlier moment of sexualized violence by equating sex with violence as bids for domination and control in the new world order of Twin Peaks. The Return announces to audiences that we are a long way from Cooper’s interception of dream messages or Leland’s desperate struggle to overcome BOB, and that for all of our nostalgia, it will be impossible to return to Twin Peaks as we remember it.

Throughout most of The Return, the “good Dale” exists in an amnesiac, near-catatonic state after escaping the Red Room in Part 2, taking the place of a Las Vegas insurance agent named Dougie Jones (a Cooper clone whom Mr. C created at one point as a decoy). MacLachlan does not so much play a new version of Cooper as allow him to restore his sensorial mode of engagement (gently touching objects with bemusement, shuffling his feet as if having just learned to walk, blinking slowly as if processing the immensity of the visual field, repeating the last word or phrase said to him in an attempt to speak by listening). Good deeds are instinctual for Dougie, just as they are instinctually understood without traditional means of language; he exposes links to organized crime and police corruption in his insurance agency by doodling on case files. The sleeper awakens only through the call of duty and call to justice, the experience of romantic and familial love, and the familiar taste of coffee and pie.

Sheryl Lee/Laura Palmer

Cooper’s cathartic awakening in Part 16 is not the first time Twin Peaks revived one of its characters. “At the end of the [1990–91] series,” Lynch said, “I felt sad. I couldn’t get myself to leave the world of Twin Peaks. I was in love with the character of Laura Palmer and her contradictions: radiant on the surface but dying inside. I wanted to see her live, move and talk” (Rodley 184). A profoundly empathetic and misunderstood film, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me allowed Lynch to tell Laura’s story, at last, from her own perspective. Chion calls it “a truly generous project because it delves into a character who, after her death, serves everyone as a prop for their own projections and fantasies, in order to say: this character existed and suffered—take an interest in this woman” (145). Focusing on the last days of Laura’s life before her murder, the film took a much darker and more experimental approach than the series, deemphasizing its folksy humor and refusing to answer questions left hanging by the Season 2 finale. Audiences at Cannes allegedly booed its premiere (Lynch and McKenna 310), and it vacated theaters in most countries practically two weeks after it opened, receiving especially harsh reviews in the US (Lucas 29). The press dismissed it as Lynch’s cynical attempt to exploit the former popularity of a canceled television series (Rodley 184), but the film nevertheless has ardent defenders—more and more in the years since its release. Writing about Lee, the critic Greil Marcus trumpeted, “The film is driven by as heedless a performance as any in the history of film” (147).

A stage actor working in Seattle, Lee was an unknown on television and film prior to Twin Peaks. Lynch and Frost cast her to play Laura’s bluish-gray corpse wrapped in plastic, as they were shooting the pilot outside of Seattle, but later created the part of Maddy for her on the basis of a “presence and a natural ability” Lynch noticed in the video footage shot for the taped picnic that Cooper studies in the pilot (Rodley 174). The character of Maddy, Laura’s twin cousin introduced in Episode 3, was important to the narrative arc of the first fourteen episodes (another instance of Peaksian doubling). However, Laura remains the most iconic character of the series, an image framed in a photograph, ubiquitous in her visibility but never legible to the town outside of a type: either the blonde, blue-eyed “good girl” (the all-American feminine ideal) or the “femme fatale” (a good girl gone bad, a moralistic cautionary tale). Ignoring or denying her suffering, the town cast her in a “double role” that rendered her inscrutable as a person, while in death she returns as an oracle of the Red Room uttering obscure clues in reversed backward speech that only the most attuned can decipher.

Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me granted Lee the opportunity to “move and talk” as Laura with a performance that demystifies her status as the image of a passive victim, an object frozen in time and memory, reconstituting Laura as a feeling subject and the most affectively responsive character in Twin Peaks. Lee constantly referred to Jennifer Lynch’s The Secret Diary of Laura Palmer to access the character’s psychology and experiences and help shape performance decisions (Hallam, Twin Peaks 104–5). For Lynch, as Justus Nieland brilliantly illuminates, melodrama and modernism are not mutually exclusive. Melodrama is “a basic category of modern experience” and its characters are “radio-active,” or “receivers and transmitters in a mediated network of affect and action” (81), an apt metaphor given Hollywood melodrama’s association with the built environment and media ecology of the Atomic Age home. To whatever degree Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me relies on modernist estrangement or an ironizing of domestic melodrama, Nieland insists that it still “depends on melodrama’s long-standing capacity to respond—through affect—to larger crises in social value, signification, and significance.” It is “modernist melodrama” (82). Lee’s performance alternates between “big” emotion and quieter, more contemplative expressions, positioning Laura as a conduit between Leland/BOB and Cooper in a circuit of affective energies. In enduring Leland/BOB’s abuse and allowing him to murder her instead of giving him possession of her body, a decision symbolized by her acceptance of the jade green ring from the Red Room, Laura passes on to that liminal space where she is able to help Cooper crack the case and ultimately free Leland from BOB at the end of Episode 16. Were BOB to possess Laura successfully, he would presumably empower the “extreme negative force” in the universe known as “Judy.”

Similar to Wise in Twin Peaks, Lee expresses suffering through tears and sobs, often using her entire body. She quivers violently or gasps for air in scenes when she realizes that BOB is in fact Leland, opening her mouth as if to let out a scream that never manages to leave her throat. Elsewhere, she does scream. Few characters in twentieth- and twenty-first-century popular culture are more linked to an actor’s scream than Laura Palmer. Twin Peaks introduced the “Laura scream” in a brief flashback to her murder at the end of Episode 8, a visceral counterpoint to the breathy voice Lee adopts for Laura in Dr. Jacoby’s tapes and other flashbacks (Laura is clearly “playing a role” there). An expression of terror then becomes a means of terrorizing in Episode 29 when Laura’s doppelganger twists her mouth open and generates reversed backward screams in the Red Room. Laura’s screams in Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me are such that the screams themselves seem painful, both for the sheer force of her voice and way Lee stretches her mouth to an unnaturally wide gape. Finally, the last scene of Part 18 in The Return ends with a scream that echoes into the night, crossing both temporal and generational boundaries. Cooper and Laura have been revived yet again, this time as somnambulant new characters Richard and Carrie, respectively, throwing the series into further ontological confusion. Visiting the Palmer house triggers Carrie’s memories of the trauma in her past life, the site of Twin Peaks’s eternal return that cannot be rewritten.

Sheryl Lee (left) as Laura Palmer and Kyle MacLachlan (right) as Dale Cooper in Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me (David Lynch, 1992).

Lee is perhaps most impressive, though, when she holds her body in steady composure, draining her face of recognizable emotions from easily identifiable causes. Before prostituting herself at the Roadhouse, she encounters two women who nearly bring her to tears. First, the Log Lady approaches her in the parking lot and touches her face, then her hand, and Laura stares at a reflection of herself in the window and deliberates the Log Lady’s concerned, poetic warning. Second, when Laura enters the bar and sees Julee Cruise on stage singing “Questions in a World of Blue,” her angelic voice and lyrics about sadness and loss seize Laura in melancholy identification. Both women seem to have been able to “hear” her, as Cooper learns to do and as others cannot. Laura takes some comfort in her companionship with her best friend Donna, but even Donna seems able to relate to her only in terms of adolescent romances (gushing over Laura’s “sweet” and “gorgeous” secret boyfriend James). Reclining upside down in a living room chair, her feet dangling over the backrest and her head lying on the footrest, Laura describes to Donna “falling faster and faster” into a void, not feeling anything until “bursting into fire forever.” More than the melodrama of tears or terrified screams, Lee opens a new dimension in Twin Peaks by personifying, once again, that melodramatic question, “what if?” (see Chapter 2). What if it were possible to live in a world where the angels haven’t “all gone away,” as she mournfully concludes in her living room daydream with Donna? What if it is possible to feel the hand of another person, and to be touched by a performance?